Alternative Food Networks, Social Capital, and Public Policy in Mexico City

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The development of AFNs in Mexico City has depended on pre-existing relationships between key actors (managers, agroecological, or transition producers and consumers);

- The most successful initiatives are those that develop expansive social capital, which suggests a verification of Woolcock’s forms of social capital: cohesion within the initiative (bonding); solidarity with other initiatives (bridging) and advocacy in public policies and programs (synergy or linking);

- The concentration of different types of social capital in the figure of the managers is an element that characterises those AFNs. These provide strengths and weaknesses to the initiatives because of the concentration of information and links centralised in a few individuals or groups.

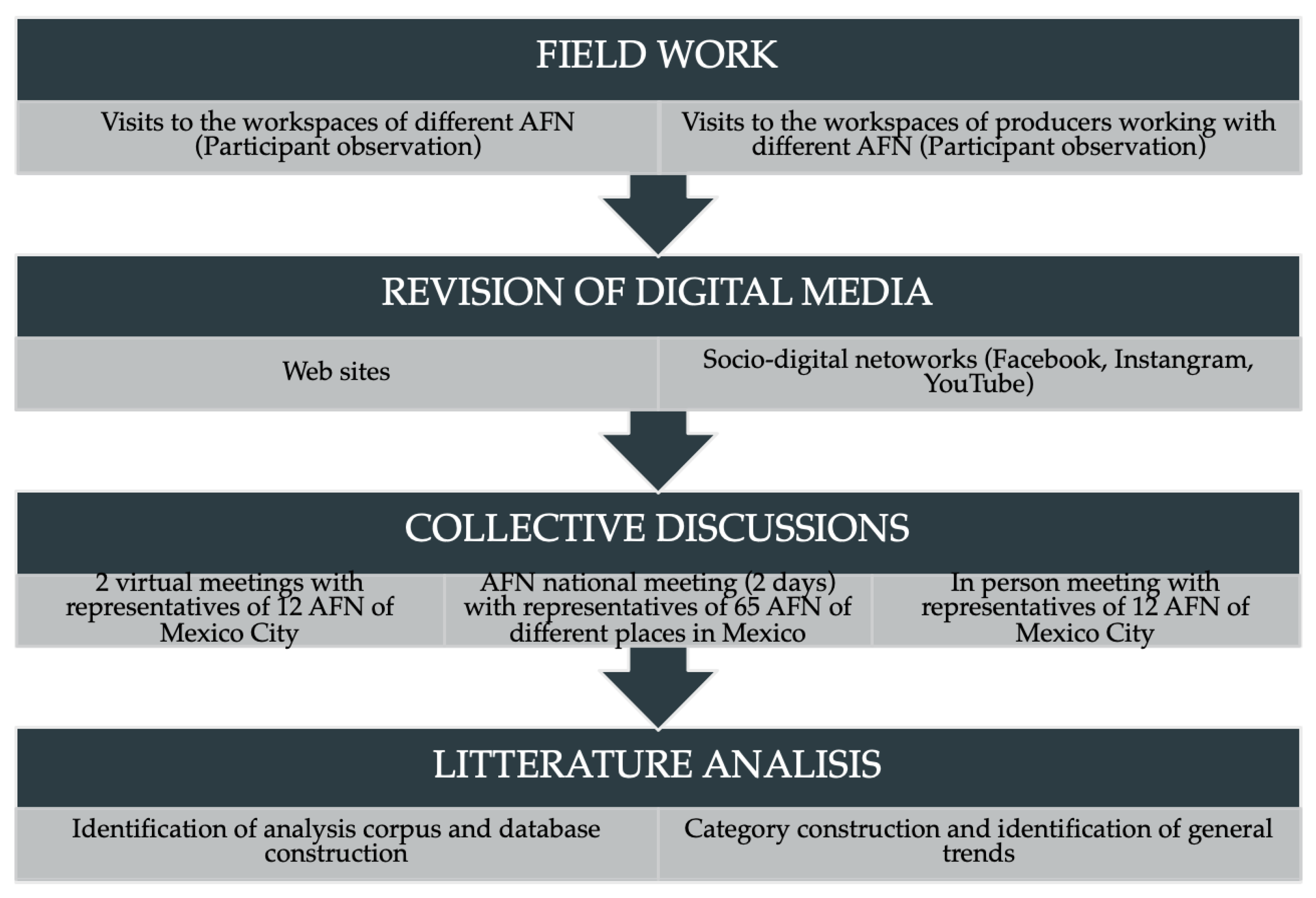

2. Materials and Methods

- Two meetings were held virtually in the last week of September and the first week of October 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Representatives of 17 AFNs participated. The topics proposed for discussion were the success factors of their initiatives, the obstacles faced in distribution, their relationships with the municipalities and the government of Mexico City, and, finally, the alliances, innovations, and proposals generated to improve their commercial and distribution activities to address the Pandemic.

- In April 2022, a national AFN Meeting was held in Mexico City. This was jointly organised by networks from different states of the Mexican Republic, the University Coordination for Sustainability of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (COUS-UNAM), the team of researchers, and the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity (CONABIO), an inter-secretariat entity allied to the project. The objectives of this meeting were to strengthen the linkage of AFNs initiatives at the national level and to exchange knowledge, experiences, and tools to reinforce their activities. Another objective was to build a common agenda to consolidate a national network with an incidence in public policies.

- In August 2022, an in-person meeting was held, with the participation of representatives of 12 initiatives. The discussion included different topics: the politics positions of alternative networks in relation to the Mexican State, the obstacles and/or benefits provided by governmental actions, the public policy orientations desired by these collectivities, and, finally, the factors of success or weaknesses of the AFNs in terms of territorial linkages and the formation of social capital.

3. Results

3.1. Social Capital in the Literature on SFSC and AFN

3.2. Alternative Food Networks in Mexico City

3.3. Elements That Characterise the AFNs as Spaces for Political Mobilisation

- -

- Socio-environmental demands. They emphasise the need to solve problems such as environmental pollution, deterioration of ecosystems, labour exploitation, health problems associated with the consumption of ultra-processed food, and unsustainable consumption, among others. To this end, operative proposals are developed in connection with producers and other actors to solve environmental, socio-economic, and health problems. These include public denunciation in connection with academic support and other civil society organisations in the defence of human rights.

- -

- Education and cultural activities. They are interested in promoting values such as responsible consumption, participation, health care, the dignity of work, and environmental care. The strategies employed differ according to human and economic resources as well as the social capital that allows them to access different media and communication spaces. These activities are developed based on actions of environmental education, food and health education, and education on socio-economic issues. Initiatives can make use of printed materials and socio-digital networks as well as the organisation of workshops, fairs, academic publications, and access to journalistic media (radio, tv., etc.).

- -

- Building links with other initiatives. The interest and investment of time and other resources in building links with other AFNs also stands out, since it allows them to exchange experiences, strategies, and relationships among their members as well as to consolidate, in some cases, common purchases to achieve greater economies of scale for the benefit of their members and consumers. The construction and strengthening of these links are promoted through the creation of spaces for dialogue and training open to other initiatives, linkage meetings with other AFNs at the regional/national/international level, as well as participation in activities with academia and the governmental sector.

- -

- Political mobilisation. We identified as political mobilisation the capacity or interest that the AFNs have to influence the construction of alternative economic and social models; in addition, some members of AFNs have individual advocacy capacity, including participation of their members in institutional spaces, normative as representatives of civil society, and members of AFN with positions in governmental and/or academic entities, for example, through mobilisation from the academic sphere in support of initiatives in spaces of debate with public administrations.

3.4. The Configuration of Social Capital: Case Studies

- Capital Verde (Green Capital)

- Zacahuitzco

- Despensa Solidaria (Solidarity Food Basket Cooperative)

- La Imposible (The Imposible)

- Mercado Alternativo de Tlalpan (Alternative Market of Tlalpan: MAT)

- Ahuejote

- Ecoquilitl

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The fieldwork conducted in the project demonstrates that, despite the involvement of multiple actors in AFNs, the participation and burdens are not equally shared.

- Although all AFNs identify with political ideals linked to sovereignty and recognise among their objectives the goal of changing food systems, only some of them operate as spaces of activism. The interest, capacity, and investment in articulating a second-level organisation that could facilitate exchanges between them and links with public bodies depend to a large extent on the social capital of their managers.

- These circumstances do not allow managers to operate the initiatives they intend to make visible. The possibility and efforts to generate second-level associations that can represent AFNs in decision-making bodies and defend their interests at the same time as having a legal status is crucial and would give them greater weight and the possibility of receiving support from external organisations with legal status to formalise collaborations through project management, addressed to reinforce digital networks, cooperative associations, and shared infrastructure such as cooperative hubs [116].

- Finally, we think relevant topics for future research should include a detailed analysis of producer and consumer participation in AFN governance, producer and consumer knowledge and representativeness in second-tier AFN organisations, and policymakers’ views of AFN organisational and mobilisation efforts.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Alternative Food Networks Websites

References

- Murdoch, J.; Marsden, T.; Banks, J. Quality, Nature, and Embeddedness: Some Theoretical Considerations in the Context of the Food Sector. Econ. Geogr. 2000, 76, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renting, H.; Marsden, T.K.; Banks, J. Understanding Alternative Food Networks: Exploring the Role of Short Food Supply Chains in Rural Development. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belletti, G.; Marescotti, A. Short Food Supply Chains for Promoting Local Food on Local Markets: Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial Development; United Nations Industrial Development Organization: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yuna, C.; Sarah, M.-A.; Arielle, C. From Short Food Supply Chains to Sustainable Agriculture in Urban Food Systems: Food Democracy as a Vector of Transition. Agriculture 2016, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiffoleau, Y.; Dourian, T. Sustainable Food Supply Chains: Is Shortening the Answer? A Literature Review for a Research and Innovation Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciarotti, C.; Torregiani, F. The Logistics of the Short Food Supply Chain: A Literature Review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel-Villarreal, R.; Hingley, M.; Canavari, M.; Bregoli, I. Sustainability in Alternative Food Networks: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giordano, C.; Graziano, P.; Lazzarini, M.; Piras, S.; Spaghi, S. Sustainable Community Movement Organisations and Household Food Waste: The Missing Link in Urban Food Policies? Cities 2022, 122, 103473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, C.J.; Hollander, G.M. Unsustainable Development: Alternative Food Networks and the Ecuadorian Federation of Cocoa Producers, 1995–2010. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratley, E.M.; Dodson, B. The Spaces for Farmers in the City: A Case Study Comparison of Direct Selling Alternative Food Networks in Toronto, Canada and Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Can. Food Stud. 2014, 1, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goszczyński, W.; Śpiewak, R. The Dark Side of the Bun: Endo and Exogenous Class Exclusions in Polish Alternative Food Network. Food Cult. Soc. 2022, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galt, R.E.; Bradley, K.; Christensen, L.; Fake, C.; Munden-Dixon, K.; Simpson, N.; Surls, R.; Van Soelen Kim, J. What Difference Does Income Make for Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) Members in California? Comparing Lower-Income and Higher-Income Households. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- King, K. Indigenous Food Systems: Battling Whiteness through Decolonization. 2016. Available online: https://ojs.library.queensu.ca/index.php/inquiryatqueens/article/view/6256 (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Bilewicz, A.; Śpiewak, R. Enclaves of Activism and Taste: Consumer Cooperatives in Poland as Alternative Food Networks. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2015, 2015, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, I.D.; Thornton, A.; Haase, D. Smart Food Cities on the Menu? Integrating Urban Food Systems into Smart City Policy Making. In Urban Food Democracy and Governance in North and South; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavuj-Borčić, L. The Production of Urban Commons through Alternative Food Practices. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2022, 23, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, A.E. Canales de Distribución Logístico-Comerciales; Ediciones de la U: Cundinamarca, Colombia, 2017; ISBN 978-958-762-675-9. [Google Scholar]

- Misleh, D. Moving beyond the Impasse in Geographies of Alternative Food Networks. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2022, 46, 1028–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celata, F.; Coletti, R. Enabling and Disabling Policy Environments for Community-Led Sustainability Transitions. Reg. Environ. Change 2019, 19, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poças Ribeiro, A.; Harmsen, R.; Feola, G.; Rosales Carréon, J.; Worrell, E. Organising Alternative Food Networks (AFNs): Challenges and Facilitating Conditions of Different AFN Types in Three EU Countries. Sociol. Rural. 2021, 61, 491–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina-Usuga, L.; Parra-López, C.; de Haro-Giménez, T. Urban Food Policies and Their Influence on the Development of Territorial Short Food Supply Chains: The Case of Cities in Colombia and Spain. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, A. Translocal Practices and Proximities in Short Quality Food Chains at the Periphery: The Case of North Swedish Farmers. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 763–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alberio, M.; Moralli, M. Social Innovation in Alternative Food Networks. The Role of Co-Producers in Campi Aperti. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda-Miquel, S.; Ruiz-Molina, E.; Gil-Saura, I. Social Innovation for Sustainability and the Common Good in Ecosystems of the Fourth Sector: The Case of Distribution Through Alternative Food Networks in Valencia (Spain). In Entrepreneurship in the Fourth Sector; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 141–167. [Google Scholar]

- Petropoulou, E.; Benos, T.; Theodorakopoulou, I.; Iliopoulos, C.; Castellini, A.; Xhakollari, V.; Canavari, M.; Antonelli, A.; Petruzzella, D. Understanding Social Innovation in Short Food Supply Chains: An Exploratory Analysis. Int. J. Food Stud. 2022, 11, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.E.M.; Russo, V. Re-Localizing ‘Legal’ Food: A Social Psychology Perspective on Community Resilience, Individual Empowerment and Citizen Adaptations in Food Consumption in Southern Italy. Agric. Hum. Values 2016, 33, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcock, M. Social Capital and Economic Development: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis and Policy Framework. Theory Soc. 1998, 27, 151–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P. Government Action, Social Capital and Development: Reviewing the Evidence on Synergy. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1119–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Schutter, O.; Dedeurwaerdere, T. Social Innovation in the Service of Social and Ecological Transformation: The Rise of the Enabling State, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 1-00-322354-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier-Merino, A.; Monachon, D.; Cotler Ávalos, H.; Rodríguez Flores, C.I.; Arizmendi Arriaga, M.D.C.; Fonseca Salazar, M.A.; Díaz López, R.; Bertrán Vilà, M.; Bak-Geller Corona, S.; Linares Mazari, E.; et al. Rumbo a Una Alimentación más Sustentable en la Ciudad de México. Realidades, Retos y Propuestas. UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2022; ISBN 978-607-30-6415-6. [Google Scholar]

- Torres_Salcido, G. Certificación participativa y mercados alternativos. Estudio de caso de la Ciudad de Mexico. Rev. Austral Cienc. Soc. 2022, 42, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ander-Egg, E. Repensando La Investigación-Acción-Participativa, 4th ed.; Grupo Editorial Lumen: Bilbao, Spain, 2003; ISBN 978-987-00-0377-9. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, F. Design Ethnography: Epistemology and Methodology; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; ISBN 3-030-60396-2. [Google Scholar]

- Michel-Villarreal, R. Towards Sustainable and Resilient Short Food Supply Chains: A Focus on Sustainability Practices and Resilience Capabilities Using Case Study. Br. Food J. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, D. The Quality ‘Turn’ and Alternative Food Practices: Reflections and Agenda. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, L.; Cox, R.; Venn, L.; Kneafsey, M.; Dowler, E.; Tuomainen, H. Managing Sustainable Farmed Landscape through ‘Alternative’ Food Networks: A Case Study from Italy. Geogr. J. 2006, 172, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maye, D.; Kirwan, J. Alternative Food Networks, Sociology of Agriculture and Food Entry for Sociopedia. Isa. 2010. Available online: http://www.sagepub.net/isa/resources/pdf/AlternativeFood-Networks.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Tregear, A. Progressing Knowledge in Alternative and Local Food Networks: Critical Reflections and a Research Agenda. J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DiVito Wilson, A. Beyond Alternative: Exploring the Potential for Autonomous Food Spaces. Antipode 2013, 45, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rover, O.J.; Da Silva Pugas, A.; De Gennaro, B.C.; Vittori, F.; Roselli, L. Conventionalization of Organic Agriculture: A Multiple Case Study Analysis in Brazil and Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buquera, R.B.; Marques, P.E.M. Trust Relationships Involving Organic Food Consumers: A Case Study in Sorocaba (in the State of São Paulo). Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural 2021, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPuis, E.M.; Goodman, D. Should We Go “Home” to Eat?: Toward a Reflexive Politics of Localism. J. Rural Stud. 2005, 21, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E. Neoliberal Subjectivities or a Politics of the Possible? Reading for Difference in Alternative Food Networks. Area 2009, 41, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E.M. Eat Local? Constructions of Place in Alternative Food Politics. Geogr. Compass 2010, 4, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, K.J. Situating the ‘Alternative’ within the ‘Conventional’—Local Food Experiences from the East Riding of Yorkshire, UK. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 35, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelmann, H.; Quiñones-Ruiz, X.F.; Penker, M. Analytic Framework to Determine Proximity in Relationship Coffee Models. Sociol. Rural 2020, 60, 458–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simon-Rojo, M. Agroecology to Fight Food Poverty in Madrid’s Deprived Neighbourhoods. Urban Des. Int. 2019, 24, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, J.A.; Selfa, T.L. The Politics of Building Alternative Agro-Food Networks in the Belly of Agro-Industry. Food Cult. Soc. 2005, 8, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moragues-Faus, A.M.; Sonnino, R. Embedding Quality in the Agro-Food System: The Dynamics and Implications of Place-Making Strategies in the Olive Oil Sector of Alto Palancia, Spain. Sociol. Rural 2012, 52, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.; Scott, S. The Convergence of Alternative Food Networks within “Rural Development” Initiatives: The Case of the New Rural Reconstruction Movement in China. Local Environ. 2016, 21, 1082–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floriš, N.; Schwarcz, P. Potential of Short Food Supply Chains, Their Role and Support within the Rural Development Policy in the Slovak Republic. Acta Reg. Environ. 2018, 15, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goszczyński, W.; Wróblewski, M. Beyond Rural Idyll? Social Imaginaries, Motivations and Relations in Polish Alternative Food Networks. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Salcido, G.; Larroa-Torres, R.M. Gobernanza y Desarrollo Territorial. Sistemas Agroalimentarios Localizados. Análisis y Políticas Públicas, 1st ed.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2021; ISBN 978-607-30-4283-3. [Google Scholar]

- Toro-Mayorga, L.; Dupuits, E. Coproduciendo El Desarrollo Territorial: Estrategias Público-Comunitarias Por El Agua y Los Alimentos En Imbabura-Ecuador. Eutopía 2021, 19, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hencelová, P.; Križan, F.; Bilková, K. Farmers’ Markets and Community Gardens in Slovakia: How Do Town Authorities Approach These Phenomena? Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2021, 28, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matacena, R. Linking Alternative Food Networks and Urban Food Policy: A Step Forward in the Transition towards a Sustainable and Equitable Food System. Int. Rev. Soc. Res. 2016, 6, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strambi, G. “Short Food Supply Chain” and Promotion of Local Food in EU and Italian Law. In Food Diversity between Rights, Duties and Autonomies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Çalik, M. European Union Short Food Supply Chain Policy and Environmental Management Accounting. In Handbook of Research on Social and Economic Development in the European Union; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 276–287. ISBN 978-1-79981-188-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gruvaeus, A.; Dahlin, J. Revitalization of Food in Sweden—A Closer Look at the REKO Network. Sustainability 2021, 13, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettenati, G. Urban Agriculture in Urban Food Policies: Debate and Practices. In Agrourbanism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, L.G. Políticas de Promoción de La Economía Social y Solidaria En La Comunidad Mocoví Com-Caia de Recreo (Santa Fe, Argentina). La Construcción de Circuitos Cortos de Comercialización En El Período 2012–2017. Punto Sur 2020, 3, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaya, B.G.; Pérez, E.M.B.; Rodríguez, D.T.G. Política Pública En La Pandemia Desde La Economía Solidaria: Circuitos Cortos de Comercialización-Ccc En Colombia (2020–2021). Apunt. Econ. Soc. 2022, 3, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottazzi, P.; Boillat, S. Political Agroecology in Senegal: Historicity and Repertoires of Collective Actions of an Emerging Social Movement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, M. Farmers’ Cooperatives to Regionalize Food Systems: A Critique of Local Food Law Scholarship and Suggestion for Critical Reconsideration of Existing Legal Tools for Changing the US Food System. Environ. Law 2017, 47, 225. [Google Scholar]

- Kapała, A.M. Legal Instruments to Support Short Food Supply Chains and Local Food Systems in France. Laws 2022, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapała, A. 17 Short Food Supply Chains in the EU Law; Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2016; pp. 209–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kapała, A.; Lattanzi, P. Mandatory Food Information in Case of Short Food Supply Chains and Local Food Systems in EU and US Legislation: A Comparative Study. Przegląd Prawa Rolnego 2021, 1, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy-Pércsi, K. Food Safety Requirements in Case of Short Food Supply Chain. Stud. Mundi 2018, 5, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Živković, L.; Pešić, M.; Schebesta, H.; Nedović, V. Exploring Regulatory Obstacles to the Development of Short Food Supply Chains: Empirical Evidence from Selected European Countries. Int. J. Food Stud. 2022, 11, SI138–SI150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxey, L. Can We Sustain Sustainable Agriculture? Learning from Small-Scale Producer-Suppliers in Canada and the UK. Geogr. J. 2006, 172, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsamzinshuti, A.; Janjevic, M.; Rigo, N.; Ndiaye, A.B. Short Supply Chains as a Viable Alternative for the Distribution of Food in Urban Areas? Investigation of the Performance of Several Distribution Schemes. In Sustainable Freight Transport: Theory, Models, and Case Studies; Zeimpekis, V., Aktas, E., Bourlakis, M., Minis, I., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 99–119. ISBN 978-3-319-62917-9. [Google Scholar]

- Haylock, K.; Connelly, S. Examining the Insider/Outsider Dimensions of Local Food System Planning: Cases from Dunedin and Christchurch New Zealand. Plan. Pract. Res. 2018, 33, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, L.S.A.; Castro, M.A.C.; Vergara, S.D.Q.; Bedoya, X.M.; Paniagua, L.M.R. Organic Food Consumption: Is It Possible to Develop Public Policy? A Case Study of Medellín. Nutr. Hosp. 2019. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6985131 (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Espluga, J.; López-García, D.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Di Masso, M.; León, A.; Acin, G. Agroecología, Conocimiento Tradicional e Identidades Locales Para La Sostenibilidad y Contra El Despoblamiento Rural. Rev. PH 2019, 98, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuitjer, G. Kurze Ketten im Lebensmittelbereich. Standort 2021, 45, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Castaño, L.S.; Cadavid Castro, M.A.; Quintero-Vergara, S.D.; Martínez-Bedoya, X.; Ríos Paniagua, L.M. Los Consumidores de Alimentos Orgánicos ¿es Posible Construir Política Pública? Nutr. Hosp. 2019, 36, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinna, S. Alternative Farming and Collective Goals: Towards a Powerful Relationships for Future Food Policies. Land Use Policy 2017, 61, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giomi, T.; Runhaar, P.; Runhaar, H. Reducing Agrochemical Use for Nature Conservation by Italian Olive Farmers: An Evaluation of Public and Private Governance Strategies. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2018, 16, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dubuisson-Quellier, S.; Lamine, C. Consumer Involvement in Fair Trade and Local Food Systems: Delegation and Empowerment Regimes. GeoJournal 2008, 73, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassatelli, R.; Davolio, F. Consumption, Pleasure and Politics: Slow Food and the Politico-Aesthetic Problematization of Food. J. Consum. Cult. 2010, 10, 202–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohest, F.; Bauler, T.; Sureau, S.; Mol, J.V.; Achten, W.M.J. Linking Food Democracy and Sustainability on the Ground: Learnings from the Study of Three Alternative Food Networks in Brussels. Politics Gov. 2019, 7, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zollet, S.; Maharjan, K.L. Resisting the Vineyard Invasion: Anti-Pesticide Movements as a Vehicle for Territorial Food Democracy and Just Sustainability Transitions. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 86, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssell, S.; Lankoski, L. Shaping Norms. A Convention Theoretical Examination of Alternative Food Retailers as Food Sustainability Transition Actors. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 63, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanciano, E. Engagement citoyen et action entrepreneuriale sont-ils conciliables? Le cas des systèmes alimentaires alternatifs. MI 2019, 23, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, M.K.; Sage, C. Food Transgressions: Ethics, Governance and Geographies. In Food Transgressions; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-315-58270-2. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley, C. The Small World of the Alternative Food Network. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pol, J. Transition Towards a Food Commons Regime: Re-Commoning Food to Crowd-Feed the World. SSRN Electron. J. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, R.; Moragues-Faus, A. Towards a Trans-Local Food Governance: Exploring the Transformative Capacity of Food Policy Assemblages in the US and UK. Geoforum 2019, 98, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Ahn, T.-K. A Social Science Perspective on Social Capital: Social Capital and Collective Action. Rev. Mex. Sociol. 2003, 65, 155–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasseni, C. Reweaving the Economy. In Beyond Alternative Food Networks: Italy’s Solidarity Purchase Groups; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2013; pp. 59–94. ISBN 978-1-350-04211-7. [Google Scholar]

- Miralles, I.; Dentoni, D.; Pascucci, S. Understanding the Organization of Sharing Economy in Agri-Food Systems: Evidence from Alternative Food Networks in Valencia. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 833–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vercher, N. Territorial Social Innovation and Alternative Food Networks: The Case of a New Farmers’ Cooperative on the Island of Ibiza (Spain). Agriculture 2022, 12, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J.; Pascucci, S. Mapping the Organisational Forms of Networks of Alternative Food Networks: Implications for Transition. Sociol. Rural. 2017, 57, 316–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortolani, L.; Grando, S.; Cucco, I. Relational Patterns in the Short Food Supply Chains Initiatives in the City of Rome: Clusters, Networks, Organisational Models. Span. J. Rural Dev. 2014, 5, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Si, Z.; Ng, C.; Scott, S. The Transformation of Trust in China’s Alternative Food Networks: Disruption, Reconstruction and Development. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buenaventura, I.; da Sousa, R.P.; López, J.D.G. Circuitos cortos de comercialización (CCC): Un enfoque desde las experiencias agroecológicas en el territorio brasilero. Coop. Desarro. 2021, 29, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsøe, M.; Kjeldsen, C. The Constitution of Trust: Function, Configuration and Generation of Trust in Alternative Food Networks. Sociol. Rural. 2015, 56, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martindale, L. “I Will Know It When I Taste It”: Trust, Food Materialities and Social Media in Chinese Alternative Food Networks. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Vastola, A.P. Fairness and Alternative Food Networks in Italy. In The Customer is NOT Always Right? Marketing Orientationsin a Dynamic Business World; Campbell, C.L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Barbera, F.; Dagnes, J.; Di Monaco, R. Quality and Price Setting by Producers in AFNs. In Alternative Food Networks: An Interdisciplinary Assessment; Corsi, A., Barbera, F., Dansero, E., Peano, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 215–243. ISBN 978-3-319-90409-2. [Google Scholar]

- Fourat, E.; Closson, C.; Holzemer, L.; Hudon, M. Social Inclusion in an Alternative Food Network: Values, Practices and Tensions. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blumberg, R.; Mincyte, D. Beyond Europeanization: The Politics of Scale and Positionality in Lithuania’s Alternative Food Networks. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2020, 27, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopczyńska, E. Economies of Acquaintances: Social Relations during Shopping at Food Markets and in Consumers’ Food Cooperatives. East Eur. Politics Soc. 2017, 31, 637–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craviotti, C. Implicancias de Un Proceso de Territorialización Incluyente a Través de Un Circuito Corto Con Valor Agregado: El Caso de Una Cooperativa de Pequeños Productores En Entre Ríos, Argentina. Sci. Territ. 2018, 6, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, E. Sourcing Food Through Social Ties: A Case Study of Starbird Fish. Food Foodways 2018, 26, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckie, M.A.; Kennedy, E.H.; Wittman, H. Scaling up Alternative Food Networks: Farmers’ Markets and the Role of Clustering in Western Canada. Agric. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamine, C.; Garçon, L.; Brunori, G. Territorial Agrifood Systems: A Franco-Italian Contribution to the Debates over Alternative Food Networks in Rural Areas. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, P. A Food Regime Genealogy. J. Peasant Stud. 2009, 36, 139–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Salcido, G. Distribución de Alimentos. Mercados y Políticas Sociales; UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs, C.C. Embeddedness and Local Food Systems: Notes on Two Types of Direct Agricultural Market. J. Rural Stud. 2000, 16, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, C.C. The practice and politics of food system localization. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baritaux, V.; Billion, C. Rôle et Place des Détaillants et Grossistes Indépendants dans la Relocalisation des Systèmes Alimentaires: Perspectives de Recherche; Post-Print; HAL: Lyon, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Le Sens Pratique; Minuit: Paris, France, 1980; ISBN 978-84-323-1302-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gantla, S.; Lev, L. Farmers’ Market or Farmers Market? Examining How Market Ownership Influences Conduct and Performance. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2015, 6, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernardi, P.; Bertello, A.; Venuti, F.; Foscolo, E. How to Avoid the Tragedy of Alternative Food Networks (AFNs)? The Impact of Social Capital and Transparency on AFN Performance. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2171–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañada, J.S.; Ochoa, C.Y. Innovación y Alimentación Sostenible. Políticas y Modelos Cooperativos de Logística y Comercialización. In La España Rural: Retos y Oportunidades de Futuro; Estrada, E.M., Ed.; Cajamar: Barcelona, Spain, 2022; pp. 333–346. [Google Scholar]

| Criteria | Design | Data Collection | Data Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependability | The design of workshops was based on key questions and minute writing shared with stakeholders. | The fieldwork lasted more than 2 years and a variety of actors participated in the meetings. | The analysis was based on dialogue among research team members and shared with stakeholders. |

| Credibility | The research design was based on a literature review and discussions with stakeholders. | Combination of sources and the dialogic character of the research. | Construction of inductive categories based on literature review, participant observation, and dialogue with social actors. |

| Transferability | The arguments discussed may be relevant to urban contexts where AFN articulation processes are incipient, mainly in mega-cities. | The data collected are particular to the case studies analysed, possibly relevant to other urban contexts of widespread social inequality. | The analysis has particular relevance for the local context, and in particular to strengthen the scope of the phenomenon under study. |

| AFN | Operating Scheme | Starting Year | Number of Linked Producers | Remuneration of Managers | Operational Decision-Making | Strategic Decision-Making |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital verde | Producers’ market | 2017 | 37 | Monetary | Assembly | Managers |

| Zacahuitzco/Mawí | Consumer Collective/Store | 2015 | 40 | Monetary (generally spent in the AFN) | Organising core | Organising core |

| Despensa Solidaria | Consumer cooperative | 2016 | 40 | Monetary | Assembly/committees | Assembly |

| La Imposible | Consumer cooperative | 2015 | 30 | Monetary (generally spent in the AFN) | Assembly/committees | Managers |

| MAT | Producers’ market | 2013 | 45 | Monetary | Managers | Managers |

| Ahuejote | Legally registered Civil association | 2017 | 4 | Monetary | Assembly | Assembly |

| Ecoquilitl | Producers’ collective | 2017 | 5 | Monetary | Producers collective with ONG support | Producers Assembly |

| Bonding | Bridging | Linking | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital verde | The coordinating committee) who coordinate market activities apply the regulations, operation, communication, and training activities internal to the AFN. | Participation in the AFN and the PGS project of the CDMX. Linking UNAM students with the project and other initiatives of AFN and urban gardens. | Participation and liaison with other civil society organisations for dialogue and advocacy with local government actors and International Organization Representation in México. |

| Zacahuitzco | Consumer cooperative with management group/cooperative members/volunteers that manage store space open to the general public. | Participation in the driving group of the National Network of AFN and representation of the AFN in discussion forums with public authorities. | Members of the collective who are present and active in governmental spaces, National Congress, and involved in advocacy actions on public policies. Articulation with a link to the national network of AFNs with incidence in university entities (UNAM). Linkage with other civil society organisations. |

| Despensa Solidaria | Management group with collaborators supporting the operation | Participation in the AFN network of Mexico City, in AFN National Network and involvement in the PGS project, articulator of several AFN in the city. Links with other cooperatives. Facilitators of organisational and training processes among AFN. | Collaboration with UNAM in projects related to sustainable food. |

| La Imposible | Management group of 16 people organised in work commissions with economic support based on their involvement in the cooperative’s activities. | Participation in the driving group of the National AFN Network and in the PGS project and the CDMX AFN Network. Promotion and accompaniment of AFN replication processes. | Presence at UNAM of members as graduate students and collaboration in UNAM`sustainable food projects. |

| MAT | 3 market spaces, each with its own team of coordinators who apply a common set of rules and ensure the operation. | Advice and accompaniment to AFN. Participation in the PGS project of CDMX and in the driving group of the National AFN Network as well as the Network of AFN of CDMX. Collaboration with UNAM in capacity building projects for AFN. | Members of the management team integrated in spaces for discussion and advocacy on public policies, presence in positions in government entities Interpersonal linkage with influential actors in public authorities and universities. Advice to local and federal government entities on local trade and food policies. |

| Ahuejote | Organisation with an associative legal figure facilitating productive and commercial projects. | Incubator of productive projects in CDMX. Recent integration of the driving group of the National AFN Network of RAA. Process facilitator and technical advisor with producers, linkage with other productive/distribution initiatives in CDMX. Collaboration with UNAM in capacity building projects for AFN. | Liaison and project management with international and national funders. Liaison with the federal program Agile Feet. Liaison with international movements (Slow food). Collaboration with UNAM in projects related to sustainable food. |

| Ecoquilitl | Collective of agro ecologically oriented producers. | Linkage with different AFN distribution spaces. Links at the local level with universities and other AFN facilitated by the civil association Redes A.C., which was an initial liaison and advisor, as well as other AFN with which they distribute their products. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pasquier Merino, A.G.; Torres Salcido, G.; Monachon, D.S.; Villatoro Hernández, J.G. Alternative Food Networks, Social Capital, and Public Policy in Mexico City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316278

Pasquier Merino AG, Torres Salcido G, Monachon DS, Villatoro Hernández JG. Alternative Food Networks, Social Capital, and Public Policy in Mexico City. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):16278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316278

Chicago/Turabian StylePasquier Merino, Ayari Genevieve, Gerardo Torres Salcido, David Sébastien Monachon, and Jessica Geraldine Villatoro Hernández. 2022. "Alternative Food Networks, Social Capital, and Public Policy in Mexico City" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 16278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316278

APA StylePasquier Merino, A. G., Torres Salcido, G., Monachon, D. S., & Villatoro Hernández, J. G. (2022). Alternative Food Networks, Social Capital, and Public Policy in Mexico City. Sustainability, 14(23), 16278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316278