The Pricing Strategy of Digital Content Resources Based on a Stackelberg Game

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Analysis of the Factors Affecting the Pricing of Digital Content Resources

2.1. Viewing Effect

2.2. Copyright Fees

2.3. Investment Costs

2.4. Revenue-Sharing Ratio

3. Methods and Results

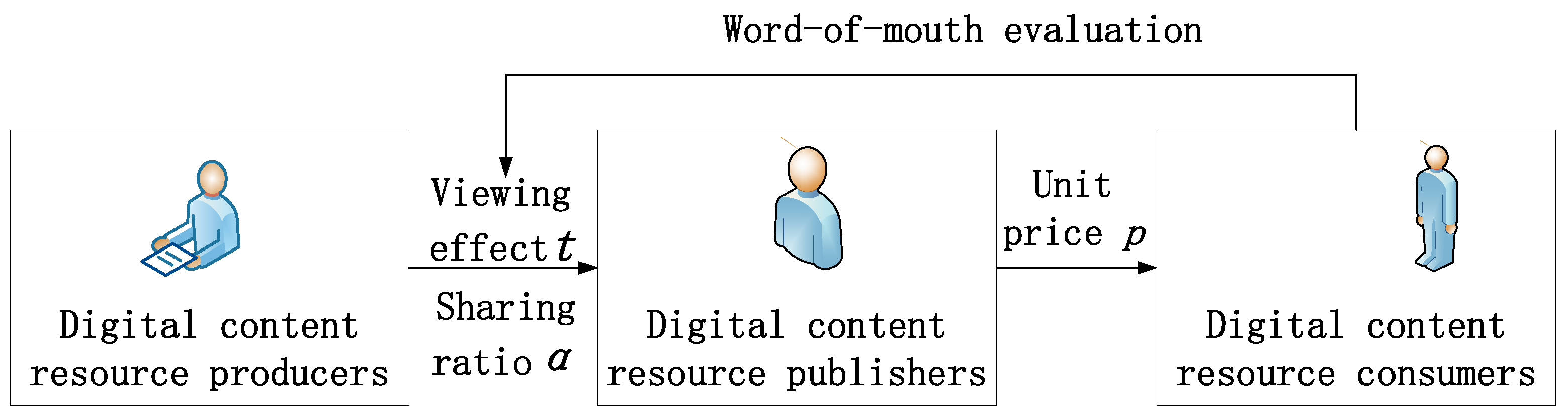

3.1. Basic Assumptions and Construction of the Stackelberg Game Model

3.2. Equilibrium Analysis of the Stackelberg Game Model

4. Simulation and Discussion

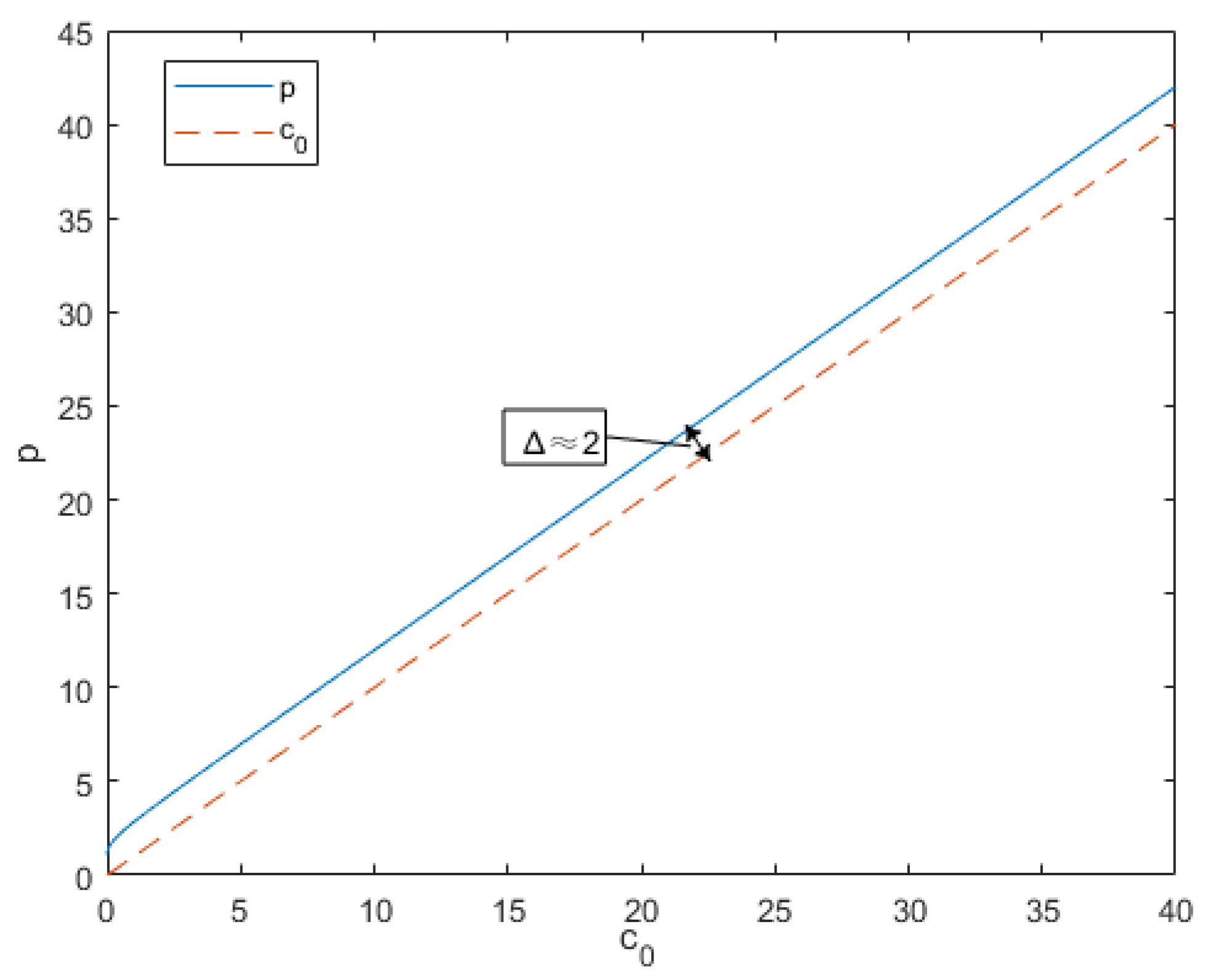

4.1. Simulation Analysis of Sales Unit Price

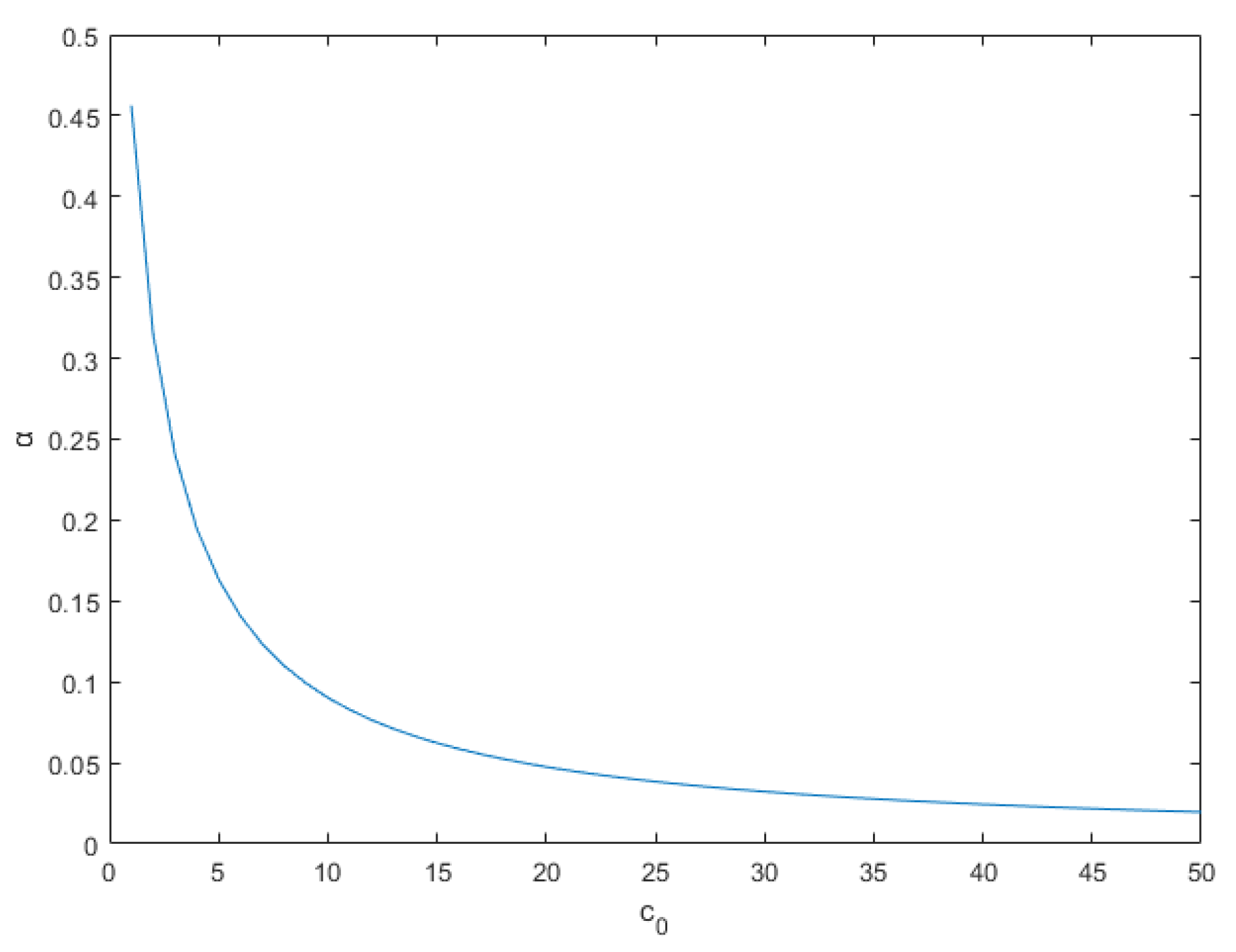

4.2. Simulation Analysis of the Revenue-Sharing Ratio

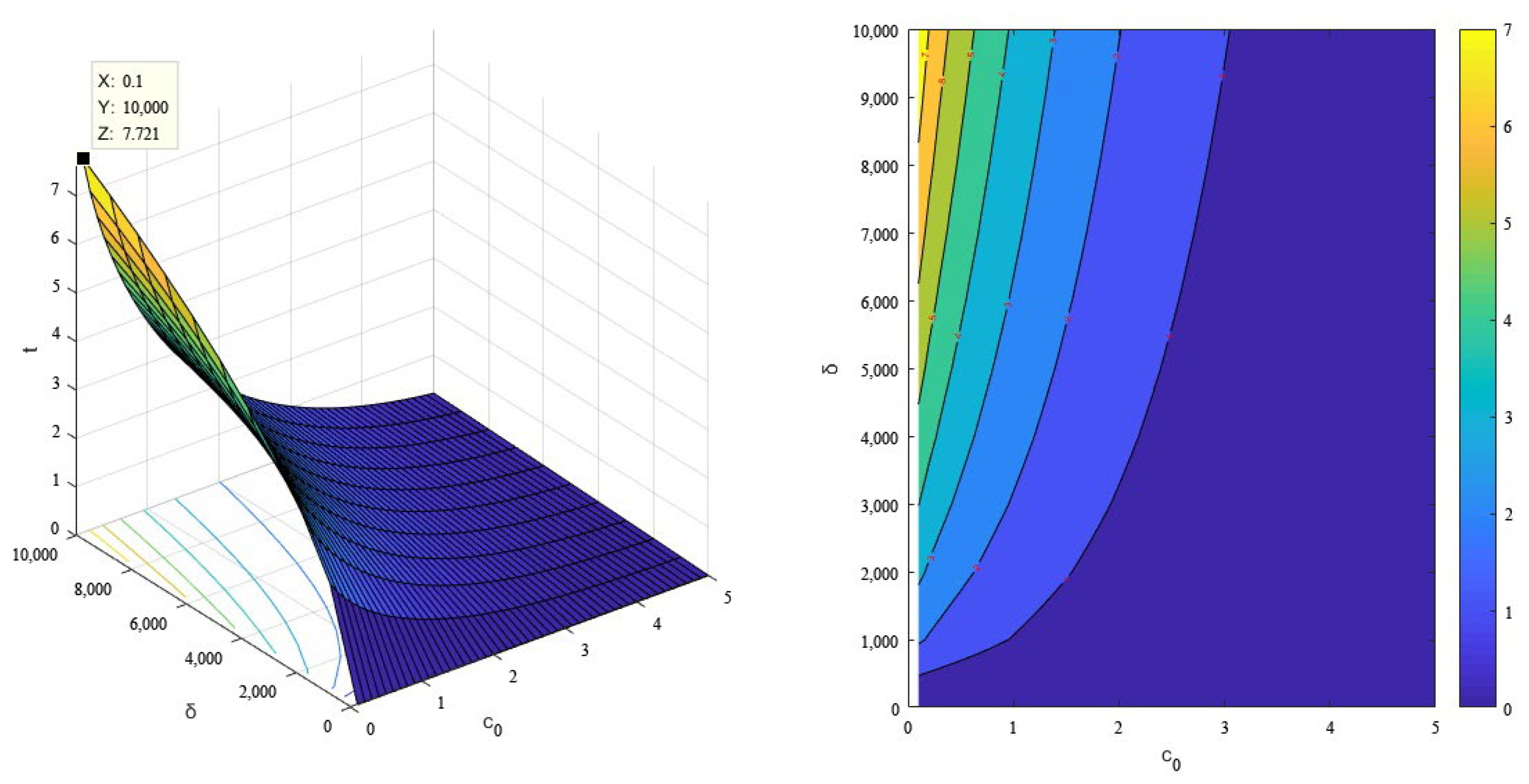

4.3. Simulation Analysis of the Viewing Effect

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vitorino, J.; Ribeiro, E.; Silva, R.; Santos, C.; Carreira, P.; Mitchell, G.R.; Mateus, A. Industry 4.0—Digital twin applied to direct digital manufacturing. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2019, 890, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.H.; Zhou, S.J. The current situation, characteristics and spillover effect of the development of digital industry in China. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2021, 38, 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Malagoli, S.; Magni, C.A.; Mastroleo, G. The use of fuzzy logic and expert systems for rating and pricing firms: A new perspective on valuation. Manag. Financ. 2007, 33, 836–852. [Google Scholar]

- Vragov, R.; Shang, D.; Lang, K.R. Dynamic auctions with Buy-It-Now pricing: A practical design model and experimental evaluation. SSRN Electron. J. 2009, 14, 39–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.; Leidinger, J. Testing patent value indicators on directly observed patent value—An empirical analysis of Ocean Tomo patent auctions. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Song, P.Y. Evaluation of TV drama projects from the perspective of investment and financing. Mod. Commun. (J. Commun. Univ. China) 2019, 41, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Na, H.S.; Hwang, J.; Hong, J.Y.J.; Lee, D. Efficiency comparison of digital content providers with different pricing strategies. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.J. Strategy analysis for a digital content platform considering perishability. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022. Early Access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Duan, Y.R. Subscription price and advertising space decisions for online content firms with reference effect. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 30, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Niyato, D.; Wang, P.; Han, Z. Data services sales design with mixed bundling strategy: A multi-dimension adverse selection approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 8826–8836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kort, P.M.; Taboubi, S.; Zaccour, G. Pricing decisions in marketing channels in the presence of optional contingent products. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 2, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, E.; Libaque-Saenz, C.F.; Park, M.C. Understanding shopping routes of offline purchasers: Selection of search-channels (online vs. offline) and search-platforms (mobile vs. PC) based on product types. Serv. Bus. 2019, 13, 305–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiller, B.; Waldfogel, J. The challenge of revenue sharing with bundled pricing: An application to music. Econ. Inq. 2013, 51, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.K.; Rakshit, A. Flexible pricing models for cloud computing based on group decision making under consensus. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2015, 16, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Luo, Q.; Qiu, L.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Optimal pricing model of digital music: Subscription, ownership or mixed? Prod.-Tion Oper. Manag. 2020, 29, 688–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppo, K.; Harri, H.; Arto, T. Cost-efficient co-creation of knowledge intensive business services. Serv. Bus. 2018, 12, 779–808. [Google Scholar]

- Shivendu, S.; Zhang, R. The impact of digitization on content markets: Prices, profit, and social welfare. Mis Q. 2020, 44, 1905–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J. A dynamic bargaining game with externalities. J. Syst. Sci. Complex. 2018, 6, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Tang, S.L.; Li, Z. Differential pricing equilibrium analysis of online video content platform—Based on the angle of capacity commitment. J. Tech. Econ. Manag. 2015, 5, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Leng, M.; Tian, X.; Song, J. Pricing the digital version of a book: Wholesale vs. agency models. INFOR Inf. Syst. Oper. Res. 2018, 56, 163–191. [Google Scholar]

- He, D.; Chen, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, T.-Y. Online learning for auction mechanism in bandit setting. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnlein, T.; Kratsch, S.; Schaudt, O. Revenue maximization in Stackelberg Pricing Games: Beyond the combinatorial setting. Math. Program. 2020, 187, 653–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Linh, C.T.; Hong, Y. Channel coordination through a revenue sharing contract in a two-period newsboy problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 3, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.S.; Lin, S.H.; Fang, C.C. Pricing and coordination with consideration of piracy for digital goods in supply chains. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 77, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linlan, Z. Protection in DRM and pricing strategies in a two-echelon digital product supply chain. Int. J. Syst. Sci. Oper. Logist. 2018, 5, 356–367. [Google Scholar]

- Song, P.Y.; Cao, S.H.; Sun, J.H. Research on copyright pricing methods of digital media content assets. Price Theory Pract. 2014, 10, 111–113. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, M.; Matus, J.A.; Martinez, M.A. Economic growth as a function of human capital, internet and work. Appl. Econ. 2014, 46, 3202–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Mo, J. Pricing of digital video supply chain: Free versus paid service on the direct distribution channel. Sustainability 2019, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Oh, E.; Shin, N. An empirical investigation of digital content characteristics, value, and flow. Data Process. Better Bus. Educ. 2015, 50, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, C.F.; Edward, N.; Jeffrey, J.T. Innovation and price: The case of digital cameras. Appl. Econ. 2009, 41, 2229–2236. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ortega, R.H.; Garcia-Sanchez, P.; Merelo-Guervos, J.J. StarTroper, a film trope rating optimizer using machine learning and evolutionary algorithms. Expert Syst. Int. J. Knowl. Eng. 2020, 37, e12525.1–e12525.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haktanir, E. Afuzzy film rating system using penthagorean fuzzy K-Means clustering. J. Mult.-Valued Log. Soft Comput. 2021, 37, 463–480. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R. TV series ratings analysis and prediction based on decision tree. Assoc. Comput. Mach. 2021, 6, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromer, J.C.; Silbey, J. Retelling copyright: The contributions of the restatement of copyright law. Columbia Univ. Libr. 2021, 3, 341–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.Q. Application of information product pricing method in copyright valuation of TV program: Basing on cus-tomer perceived value and conjoint analysis methods. Inf. Res. 2017, 1, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Q.; Hou, Z.P.; Bao, J.L.; Yuan, Q.J. Research on influencing factors of the pricing of digital publication from the perspective of consumer. Inf. Stud. Theory Appl. 2014, 37, 53–56, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S. Hollywood movies and China: Analysis of Hollywood globalization and relationship management in China’s cinema market. Glob. Media China 2018, 3, 177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Cheryl, F. Sharing with creative commons: A business model for content creators. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2010, 2, 64–93. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, D. An empirical analysis of the factors influencing the box office of 3D movies in my country. Mod. Commun. (J. Commun. Univ. China) 2012, 34, 139–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazali, L.; Islam, R. Critical determinants of box office success for the Malaysian film industry. Int. J. Bus. Syst. Res. 2021, 15, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, G. Sunk costs and the dynamics of creative industries. In The Oxford Handbook of Creative Industries; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 351–386. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Rhee, B.; Schmidt, G.; van der Veen, J.A.; Venugopal, V. Revenue-sharing contracts across an extended supply chain. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, S. Supply chain coordination with revenue sharing contract in prospect theory. IAENG Int. J. Appl. Math. 2017, 47, 484–489. [Google Scholar]

- Nina, B.; Seethu, S.; Andrei, S. Revenue sharing vertical contracts in the movie industry: A theoretical analysis. Rev. Mark. Sci. 2019, 17, 81–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hansser, F.A. Revenue-sharing in movie exhibition and the arrival of sound. Econ. Inq. 2010, 40, 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canbulut, G.; Kse, E.; Arik, O.A. Handling of revenue sharing contracts within the scope of game theory. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.P.; Wang, J.J.; Perera, S.; Shi, J.J. Coordination of a supply chain with Nash bargaining fairness concerns. Transp. Res. Part E: Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 159, 102627.1–102627.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Y. Pareto and Kaldor–Hicks improvements with revenue-sharing and wholesale-price contracts under manufacturer rebate policy. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 298, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molto, M.J.G.; Georgantzis, N.; Orts, V. Cooperative R&D with endogenous technology differentiation. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2010, 14, 461–476. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Guo, Z.; Wang, J.; Gu, S. Pricing digital products with cost and competition considered in electronic commerce. J. Northeast. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2006, 7, 724–727. [Google Scholar]

- Bossert, W.; Sprumont, Y. Every choice function is backwards-induction rationalizable. Econometrica 2013, 81, 2521–2534. [Google Scholar]

- Carlos, A.F.; Klaus, R. Does backwards induction imply subgame perfection? Games Econ. Behav. 2016, 103, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.J. The new root-seeking formula and new discriminant method of cubic equation. J. Hainan Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 1989, 2, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, J.V.; Guerreiro, R. Factors explaining a cost-based pricing essence. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 1850–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A. Cost-plus pricing when joint costs are present. Omega 1985, 13, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.L.; Ho, C.Y. A Mixed-Initiative Model for Quality-Based E-Services Pricing. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Information Technology: New Generations, IEEE Computer Society, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–14 April 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avinadav, T.; Chernonog, T.; Meilijson, I.; Perlman, Y. A consignment contract with revenue sharing between an app developer and a distribution platform. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 243, 108322.1–108322.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, N.; Mo, J.; Park, J. Revenue sharing of ISP and CP in a competitive environment: Game theory for networks. Springer Int. Publ. 2016, 174, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Jahanmir, S.F.; Cavadas, J. Factors affecting late adoption of digital innovations. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.L.; Wang, Z.; Dai, M.Z. The imposition strategy and improvement of the KTV music copyright fees: Based on the cooperative game theory and the Shapley model. J. Tech. Econ. Manag. 2014, 2, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, C.-G.; Baek, H.; Lee, S.-G. Erratum to: Revisiting media selection in the digital era: Adoption and usage. Serv. Bus. 2016, 10, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janmohammadi, M. Investigating the impact of digital media advertising content on accepting or rejecting the message mediated by advertising value and modifier of brand trust and marketing innovation (case study: Citizens of the west of Tehran). Int. J. Electron. Mark. Retail. 2022, 13, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter Representation | Basic Meaning |

|---|---|

| Viewing effect | |

| Investment difficulty coefficient of the producers | |

| Investment scale | |

| Copyright fee coefficient | |

| Copyright fee | |

| Revenue-sharing ratio of the producers | |

| Revenue-sharing ratio of the publishers | |

| Single broadcast price | |

| Single broadcast cost | |

| Constant coefficient of the sales model | |

| Total sales volume | |

| Total revenue | |

| Total cost of the publishers |

| Factor Name | Theoretical Formula |

|---|---|

| Single broadcast price | |

| Revenue-sharing ratio | |

| Viewing effect |

| Factor Name | Influence | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Copyright fees | Positive | Higher copyright fees will offset some of the investment expenditures in advance, encouraging the producers to strive to improve the viewing effect |

| Investment difficulty | Negative | Smaller investment difficulty will increase the enthusiasm of the producers and increase their expectations of the viewing effect |

| Sales coefficient | Positive | A higher sales coefficient encourages the producers and publishers to work hard to improve the viewing effect and increase the market broadcast revenue |

| Single broadcast cost | Negative | Lower unit cost will enable the producers to obtain a higher revenue-sharing ratio and use the advantage of low prices to increase sales and revenue |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Ni, Y. The Pricing Strategy of Digital Content Resources Based on a Stackelberg Game. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16525. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416525

Zhao Y, Ni Y. The Pricing Strategy of Digital Content Resources Based on a Stackelberg Game. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16525. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416525

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yan, and Yuan Ni. 2022. "The Pricing Strategy of Digital Content Resources Based on a Stackelberg Game" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16525. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416525