Plantitas/Plantitos Preference Analysis on Succulents Attributes and Its Market Segmentation: Integrating Conjoint Analysis and K-means Clustering for Gardening Marketing Strategy

Abstract

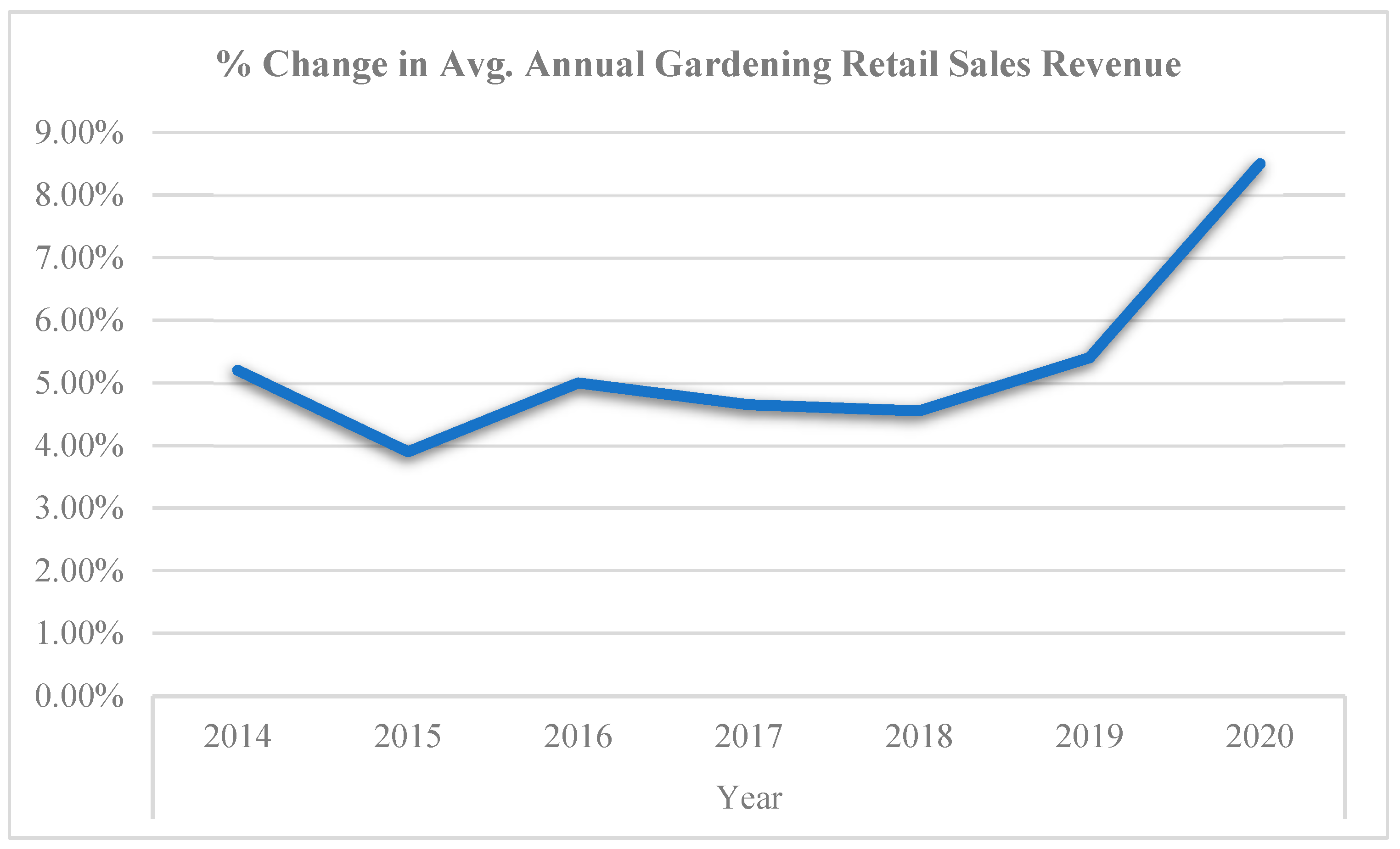

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

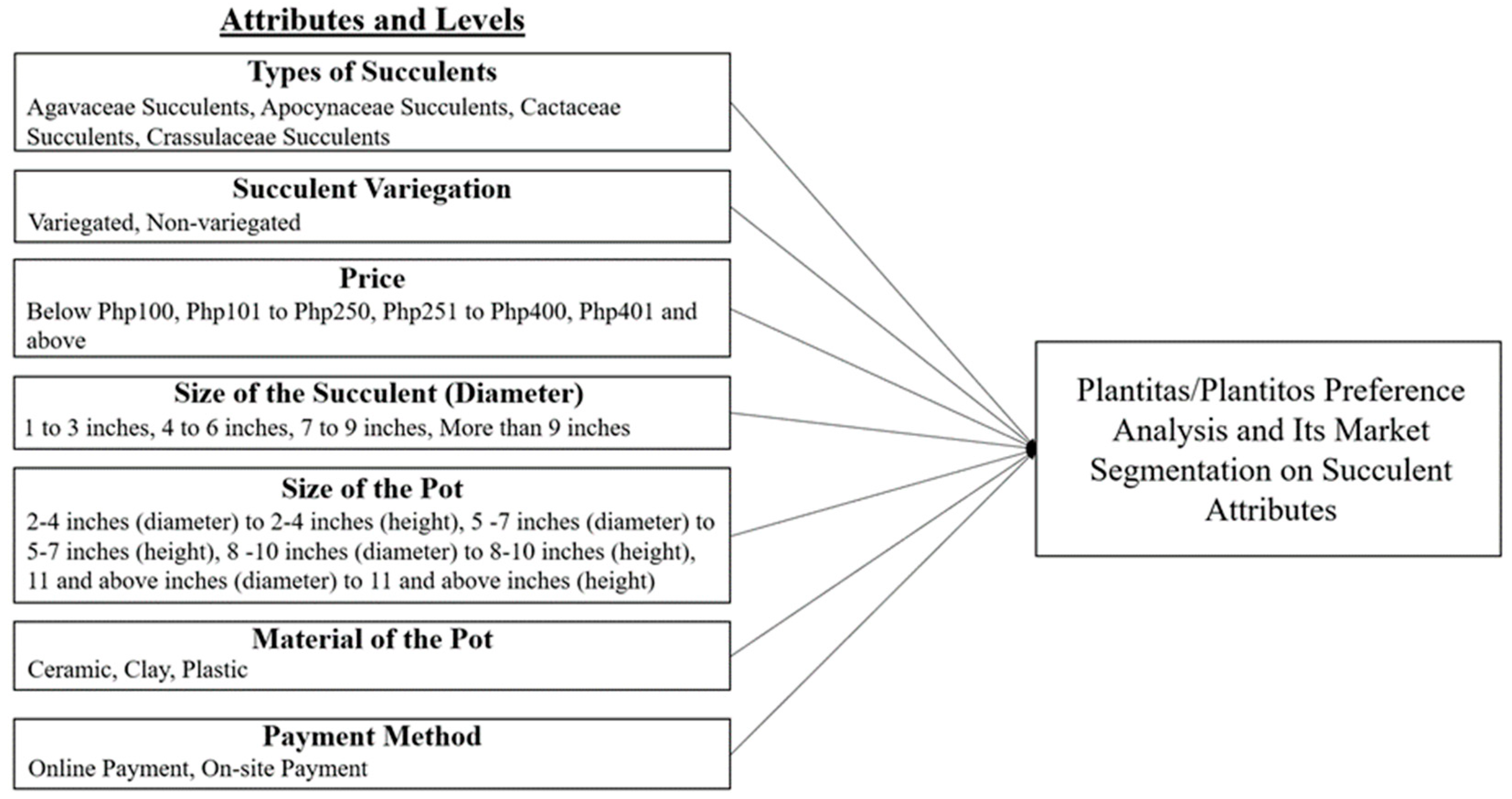

2.1. Conceptual Framework and Research Design

2.2. Selection of Attributes and Levels

2.3. Respondents of the Study

2.4. Conjoint Analysis

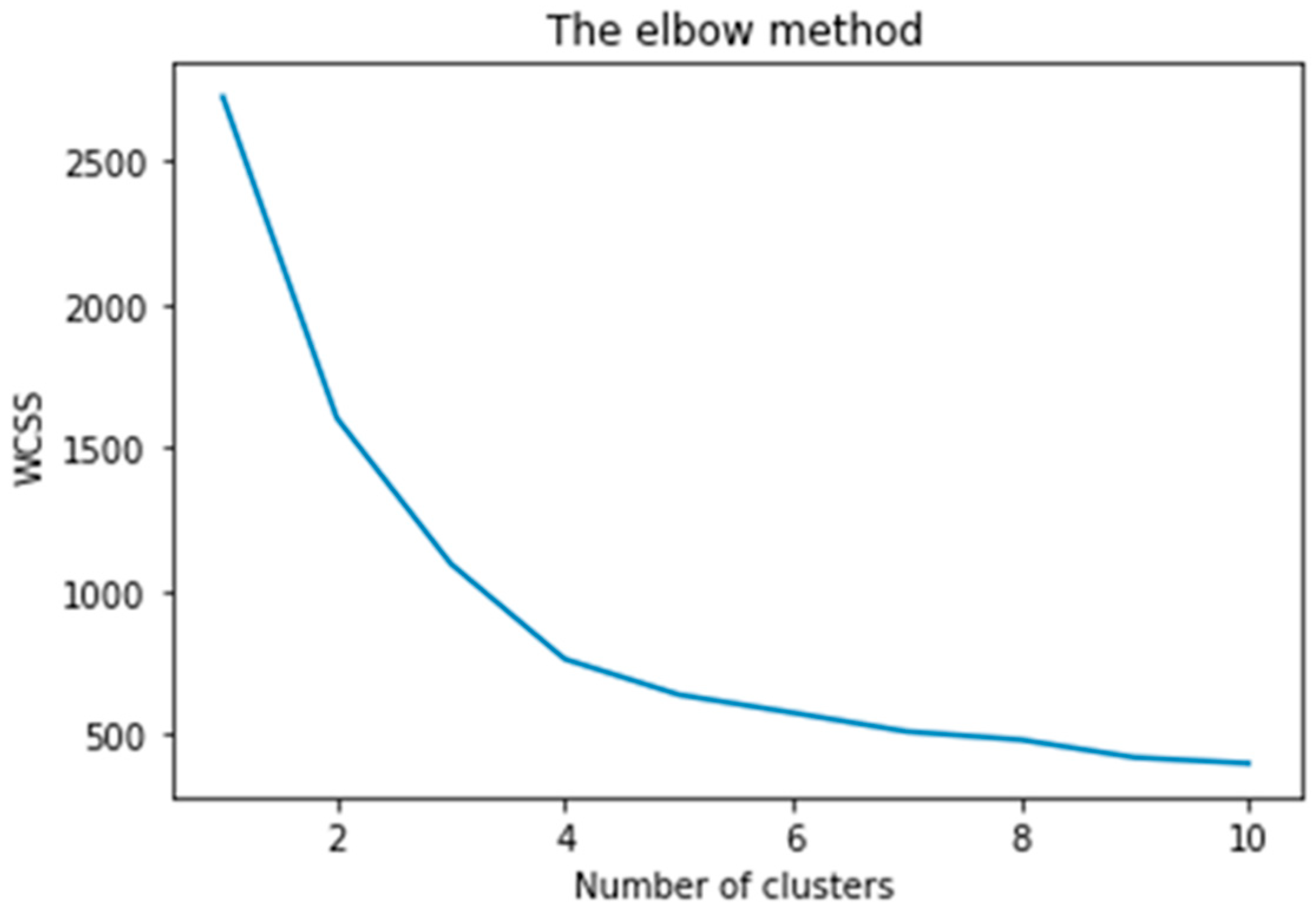

2.5. K-Means Cluster

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Conjoint Analysis Results

3.2. Conjoint Analysis Discussion

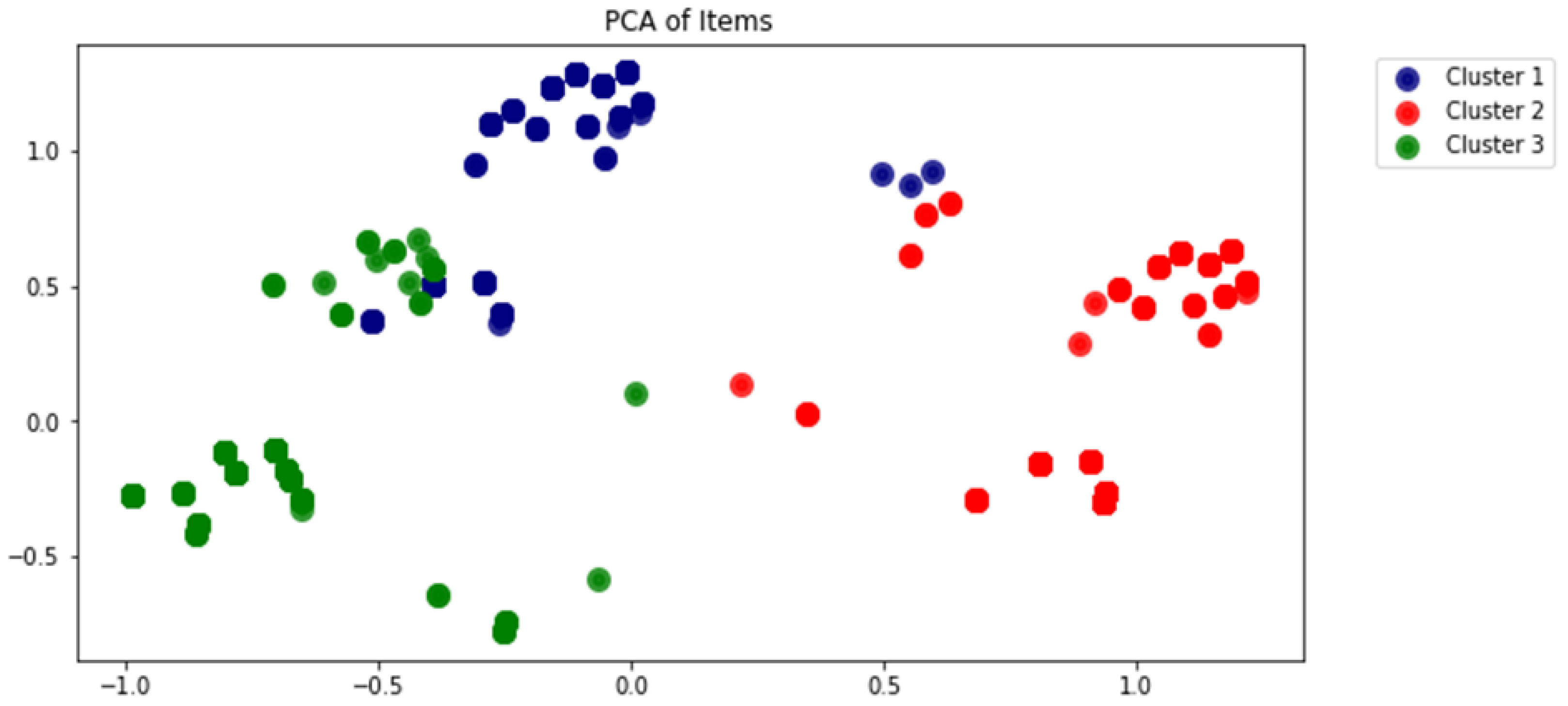

3.3. K-Means Cluster Results

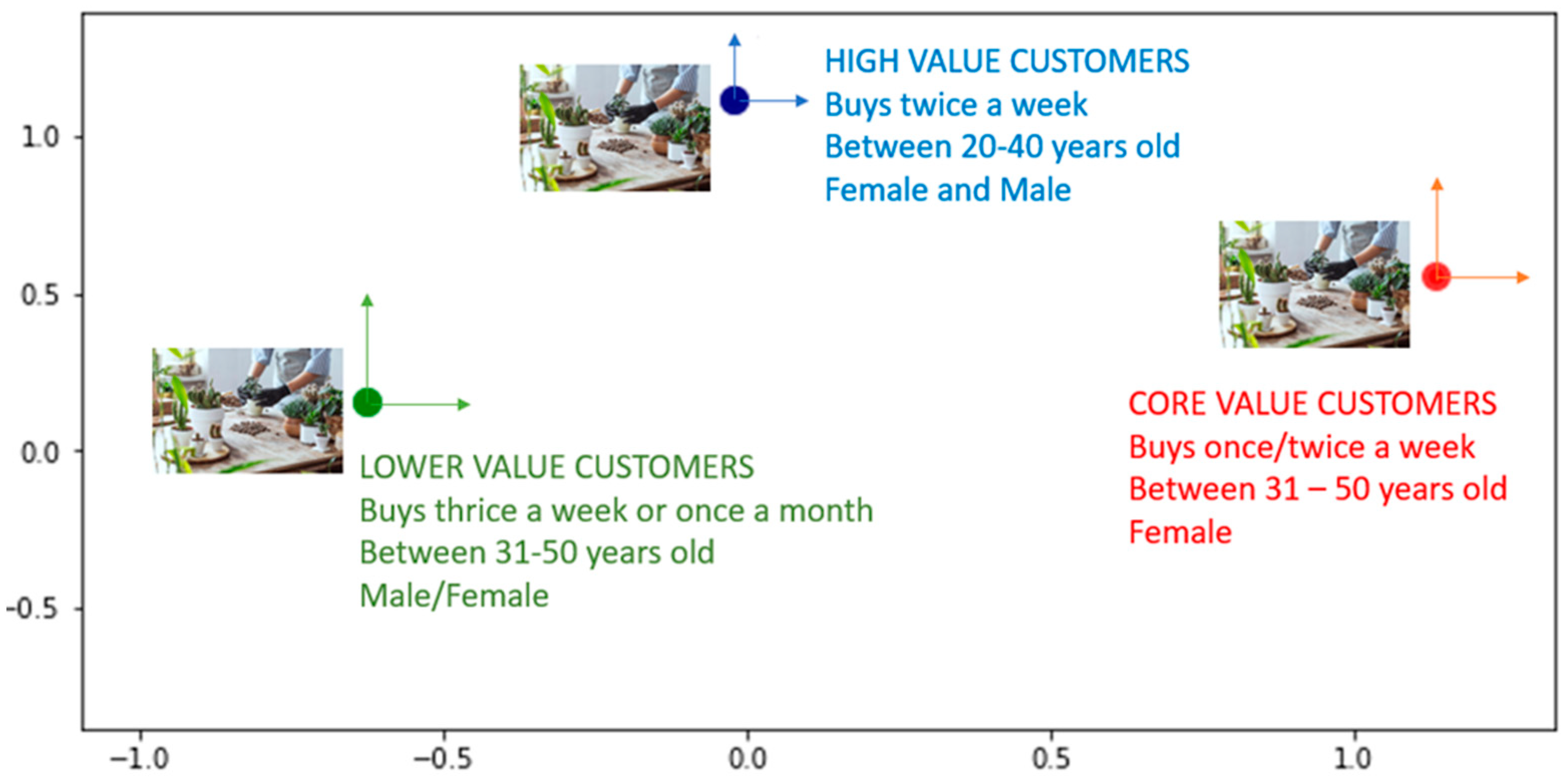

3.4. K-Means Cluster Discussion

4. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Attributes | Levels |

|---|---|

| Types of Succulents |  Agavaceae Succulents  Apocynaceae Succulents  Cactaceae Succulents  Crassulaceae Succulents |

References

- Schmutz, U.; Turner, M.L.; Williams, S.; Devereaux, M.; Davies, G. The Benefits of Gardening and Food Growing for Health and Wellbeing; Garden Organic and Sustain: Ting Kok, Hong Kong, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- del Monte, P. How “Plant Parenting” Can Aid in Coping Amid the Pandemic; CNN Philippines: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, J.A. Gardening for Peace of Mind during the COVID-19 Crisis. Acad. Lasalliana J. Educ. Humanit. 2013, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beleo, E. Demand for flowerpots on a surge amid COVID-19 lockdowns. Manila Bulletin, 29 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dave. Millennial Households Continue to Provide Optimism for the Lawn and Garden Industry. Available online: https://garden.org/newswire/view/dave/22/Millennial-Households-Continue-to-Provide-Optimism-for-the-Lawn-and-Garden-Industry/ (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Coppess, A. THE RISE IN GARDENING RETAIL DURING COVID-19. Available online: https://www.brecks.com/blog/covid-gardening-retail-boom (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Marcos, A. The rise of Plantitas and Plantitos. Daily Tribune, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Succulent Plant Market Size and Share, Scope, Trends and Forecast; Verified Market Research: Pune, India, 2019.

- Succulent Plant Market 2021 is estimated to clock a modest CAGR of 17.9%Â during the forecast period 2021–2026 with Top Countries Data. 2News, 2021.

- Succulent Plant Market Size, Trends & Analysis, By Type, By Products (Single Head, Bulls, Fascicular, Old Pile, Combination), By Application (Household, Commercial, Others), By Region- Global Forecast To 2027; Reports and Data. Available online: https://www.reportsanddata.com/report-detail/succulent-plant-market (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Daigle, T. DIY Succulents: From Placecards to Wreaths, 35+ Ideas for Creative Projects with Succulents; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cabahug, R.A.M.; Nam, S.Y.; Lim, K.B.; Jeon, J.K.; Hwang, Y.J. Propagation Techniques for Ornamental Succulents. Flower Res. J. 2018, 26, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Books, A.P. Dwarf Succulents. Nature 1932, 130, 613–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, F.; Sattler, H. Preference Measurement with Conjoint Analysis: Overview of State-of-the-Art Approaches and Recent Developments. GfK Keting Intell. Rev. 2011, 3, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.K.S.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Libiran, M.A.D.C.; Lontoc, Y.M.A.; Lunaria, J.A.V.; Manalo, A.M.; Miraja, B.A.; Young, M.N.; Chuenyindee, T.; Persada, S.F.; et al. Consumer Preference Analysis on Attributes of Milk Tea: A Conjoint Analysis Approach. Foods 2021, 10, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.E.; Srinivasan, V. Conjoint Analysis in Consumer Research: Issues and Outlook. J. Consum. Res. 1978, 5, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Suzianti, A.; Dewi, A.P. Consumer preference analysis on flute attributes in Indonesia using conjoint analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Design Research and Education 2014 ICADRE14, Singapore, 16–18 July 2014 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Veitch, J.; Salmon, J.; Deforche, B.; Ghekiere, A.; Van Cauwenberg, J.; Bangay, S.; Timperio, A. Park attributes that encourage park visitation among adolescents: A conjoint analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 161, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutar, G.N.; Turner, J.P. Students’ preferences for university: A conjoint analysis. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2002, 16, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattin, P.; Wittink, D.R. Commercial Use of Conjoint Analysis: A Survey. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariji, M. Conjoint analysis of consumer preference for bluefin tuna. Fish. Sci. 2010, 76, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.E.; Krieger, A.M.; Wind, Y. Thirty Years of Conjoint Analysis: Reflections and Prospects. Interfaces 2001, 31, S56–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, C.; Ozuomba, S.; Kalu, C. Application of K-Means Algorithm for Efficient Customer Segmentation: A Strategy for Targeted Customer Services. Int. J. Adv. Res. Artif. Intell. 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chiciudean, G.; Chiciudean, D. Customer Segmentation by Attributes Considered Important During the Buying Decision-Making Process for Cheese. Bull. UASVM Hortic. 2013, 70, 287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Kodinariya, T.M.; Makwana, P.R. Review on determining number of Cluster in K-Means Clustering. Int. J. 2013, 1, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Vigneau, E.; Qannari, E.; Navez, B.; Cottet, V. Segmentation of consumers in preference studies while setting aside atypical or irrelevant consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 47, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, M.; Sivakumar, V.; Jayakumar, G.D.S. Segmentation of Indian shoppers based on store attributes. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2009, 3, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Kumar, S. Comparative Analysis of K-Means and Fuzzy C-Means Algorithms. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, M.; Mohseni, M.; Soofi, M. Clustering Stock Market Companies via K-Means Algorithm. Kuwait Chapter Arab. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Townsley-Brascamp, W.; Marr, N. Evaluation and Analysis of Consumer Preferences for Outdoor Ornamental Plants. Acta Hortic. 1995, 391, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.J.; Gale, S.W.; Hinsley, A.; Gao, J.; St. John, F.A.V. Using consumer preferences to characterize the trade of wild-collected ornamental orchids in China. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 11, e12569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihn, A.; Khachatryan, H.; Campbell, B.; Hall, C.; Behe, B. Consumer preferences for organic production methods and origin promotions on ornamental plants: Evidence from eye-tracking experiments. Agric. Econ. 2016, 47, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behe, B.K.; Campbell, B.L.; Khachatryan, H.; Hall, C.R.; Dennis, J.H.; Huddleston, P.T.; Fernandez, R.T. Incorporating Eye Tracking Technology and Conjoint Analysis to Better Understand the Green Industry Consumer. HortScience 2014, 49, 1550–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behe, B.; Nelson, R.; Barton, S.; Hall, C.; Safley, C.D.; Turner, S. Consumer Preferences for Geranium Flower Color, Leaf Variegation, and Price. HortScience 1999, 34, 740–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugie, K.; Yue, C.; Watkins, E. Consumer Preferences for Low-input Turfgrasses: A Conjoint Analysis. HortScience 2012, 47, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshreshtha, K.; Bajpai, N.; Tripathi, V. Consumer preference for electronic consumer durable goods in India: A conjoint analysis approach. Int. J. Bus. Forecast. Mark. Intell. 2017, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrzan, K. Three kinds of order effects in choice-based conjoint analysis. Mark. Lett. 1994, 5, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.E.; Helsen, K. Cross-Validation Assessment of Alternatives to Individual-Level Conjoint Analysis: A Case Study. J. Mark. Res. 1989, 26, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axiom Marketing. Gardening Insight Survey: Gardening in a COVID-19 World. (2020, November); Axiom: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R.M.; Qureshimatva, U.M.; Maurya, R.R.; Solanki, H.A. A checklist of succulent plants of Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. Trop. Plant Res. 2016, 3, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakr, R.O. A Comprehensive Review of the Aizoaceae Family: Phytochemical and Biological Studies. Nat. Prod. J. 2021, 11, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, R.; Royer, F. Weeds of North America. Nativ. Plants J. 2015, 16, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, H.G.; Moran, V.C.; Hoffmann, J.H. Biological control of tropical weeds using arthropods (Rangaswami Muniappan ed.); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Deng, M. Crassulaceae. In Identification and Control of Common Weeds: Volume 2; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 475–486. [Google Scholar]

- Arizaga, S.; Ezcurra, E. Propagation mechanisms in agave macroacantha (Agavaceae), a tropical arid-land succulent rosette. Am. J. Bot. 2002, 89, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggli, U.; Arroyo-Leuenberger, S.; Bayer, M.B.; Bogner, J.; Eggli, U.; Forster, P.I.; Hunt, D.R.; Jaarsveld, E.J.; Meyer, N.L.; Newton, L.; et al. Illustrated Handbook of Succulent Plants: Monocotyledons; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti, M.; Leverette, M.M. How to Grow and Care for Agave; The Spruce: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkiss, R.J. Apocynaceae. The Succulent Plant Page, 2 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, N. How To Care For A Hoya Houseplant; Joy Us Garden: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Groen, A.H. Apocynum androsaemifolium: Introductory; Fire Effects Information System (FEIS): Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- What Is a Cactus? Macmillan Dictionary Blog. Available online: https://www.macmillandictionaryblog.com/cactus (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- West Coast Gardens. 5 Care Tips to Keep Your Cactus Happy—Tips. West Coast Gardens, 15 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cactus Light Requirements—How Much Light do Cacti Need? Plant Index, 17 June 2022.

- Grant, B.L. Stonecrop Plant—Planting Stonecrop in Your Garden; Gardening Know How: Bedford, OH, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R. All You Need to Know About Stonecrop Succulents; Succulent City: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, D. Top Tips for Growing Sedum Stonecrop the Right Way; Plant Delights Nursery: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, H.J.; Agnew, N.H.; Behe, B.K. Consumer Preference for Leaf Variegation, Flower Color, Price and Use of New Guinea Imfatiens. HortScience 1992, 27, 606c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachatryan, H.; Choi, H.J. Factors Affecting Consumer Preferences and Demand for Ornamental Plants; UF/IFAS Extension: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Faith, D.O.; Agwu, M.E. A Review of the Effect of Pricing Strategies on the Purchase of Consumer Goods. Res. Manag. Sci. Technol. 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.; Behe, B.K.; Barton, S.S.; Page, T.J.; Schutzki, R.E.; Muzii, K.; Fernandez, R.T.; Haque, M.T.; Brooker, J.; Hall, C.R.; et al. Consumers Preferences for Plant Size, Type of Plant Material and Design Sophistication in Residential Landscaping. J. Environ. Hortic. 2000, 18, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Bühler, J.; van Dusschoten, D.; Climent, J.; Postma, J.A. Pot size matters: A meta-analysis of the effects of rooting volume on plant growth. Funct. Plant Biol. 2012, 39, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegel, J. The 13 Best Pots for Indoor Plants in 2021. Bustle, 20 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, N.; Alajmi, W.Y.A. A Study on Consumer Preferences for E Shopping with Reference to Bahraini Consumers. SSRN Electron. J. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanthi, R.; Desti, K. Consumers’ perception on online shopping. J. Mark. Consum. Res. 2015, 13, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D. Likert Scale: Explored and Explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.K.S.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Young, M.N.; Diaz, J.F.T.; Chuenyindee, T.; Kusonwattana, P.; Yuduang, N.; Nadlifatin, R.; Redi, A.A.N.P. Students’ Preference Analysis on Online Learning Attributes in Industrial Engineering Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Conjoint Analysis Approach for Sustainable Industrial Engineers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamerly, G.; Elkan, C. Learning the k in K-means. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2003, 16, 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawan, C.; Setyosari, P.; Kamdi, W.; Ulfa, S. Electrical engineering student learning preferences modelled using k-means clustering. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 20, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Ariff, N.M.; Bakar, M.A.; Zamzuri, Z.H. Academic preference based on students’ personality analysis through k-means clustering. Malays. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2020, 16, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orme, B.K.; King, W.C. Conducting Full-Profile Conjoint Analysis over the Internet. Quirk’s Media, 1 July 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, V.D. Determinants of Milk Tea Selection In Ho Chi Minh City. Multidiscip. Res. Dev. 2020, 2, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zotz, G.; Hietz, P.; Schmidt, G. Small plants, large plants: The importance of plant size for the physiological ecology of vascular epiphytes. J. Exp. Bot. 2001, 52, 2051–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, A.; Lohr, V. Does Plant Color Affect Emotional and Physiological Responses to Landscapes? Acta Hortic. 2004, 639, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; ŚLusarczyk, B.; Hajizada, S.; Kovalyova, I.; Sakhbieva, A. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Online Consumer Purchasing Behavior. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2263–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaques, L. Plant Containers, Pots, and Planters—What Material Is the Best? Gardener’s Path, 7 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M. Do Houseplants Live Longer in Plastic or Ceramic Pots? HomeGuides SF Gate, 25 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Coblentz, J. Why Are Plant Pots So Expensive? (Find Out Now!). Upgraded Home. 2021. Available online: https://upgradedhome.com/why-are-plant-pots-so-expensive/ (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Behe, B.K.; Campbell, B.L.; Hall, C.R.; Khachatryan, H.; Dennis, J.H.; Yue, C. Consumer Preferences for Local and Sustainable Plant Production Characteristics. HortScience 2013, 48, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fränti, P.; Sieranoja, S. How much can K-means be improved by using better initialization and repeats? Pattern Recognit. 2019, 93, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, O.R.; Di Paola, B.; Fazio, C. K-means Clustering to Study How Student Reasoning Lines Can Be Modified by a Learning Activity Based on Feynman’s Unifying Approach. EURASIA J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.T. Consumer Preference Analysis on Mobile Service Providers: A Case Study of Foreign Students in Taiwan. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 6th International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences (ICETAS 2019), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 20–21 December 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zeng, Q.; Chang, M.; Tong, Q.; Su, J. A Prediction Model of Customer Churn considering Customer Value: An Empirical Research of Telecom Industry in China. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.; Singh, V.; Fay, S. An Empirical Study of the Impact of Nonlinear Shipping and Handling Fees on Purchase Incidence and Expenditure Decisions. Mark. Sci. 2006, 25, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, A.B.; Maxham, J.G. Return Shipping Policies of Online Retailers: Normative Assumptions and the Long-Term Consequences of Fee and Free Returns. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.H.; Shen, G.C.; Liang, C.L. The effect of threshold free shipping policies on online shoppers’ willingness to pay for shipping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 48, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.R.; Fardous, J. Effects of Value-Added Service on Customer Retention: “A case study on Telenor Bangladesh”. Master’s Thesis, Independent Thesis. 2020. Available online: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1591538&dswid=1931 (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Owens, B. How to set your free shipping threshold. Whiplash, 30 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kluz, L. How to Offer Free Shipping & How to Calculate Your Free Shipping Threshold. A Better Lemonade Stand, 2 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.-F.; Chou, L.-W.; Huang, H.-C.; Tu, H.-M. Perceived COVID-19-related stress drives home gardening intentions and improves human health in Taiwan. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 78, 127770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrose, G.; Das, K.; Fan, Y.; Ramaswami, A. Comparing happiness associated with household and community gardening: Implications for Food Action Planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 230, 104593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Cheong, J.C.; Lee, J.S.H.; Tan, J.K.N.; Chiam, Z.; Arora, S.; Png, K.J.Q.; Seow, J.W.C.; Leong, F.W.S.; Palliwal, A.; et al. Home Gardening in Singapore: A feasibility study on the utilization of the vertical space of retrofitted high-rise public housing apartment buildings to increase urban vegetable self-sufficiency. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 78, 127755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, J.; Diekmann, L.; Egerer, M.H.; Lin, B.B.; Ossola, A.; Marsh, P. Experiences of gardening during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Place 2022, 76, 102854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, L.; Morris, S.L.; Pollard, T.M. Community Gardening and wellbeing: The understandings of organisers and their implications for gardening for health. Health Place 2022, 75, 102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Prahalad, V. Barriers and enablers for private residential urban food gardening: The case of the city of hobart, Australia. Cities 2022, 126, 103689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheromm, P.; Javelle, A. Gardening in an Urban Farm: A way to reconnect citizens with the soil. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 72, 127590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerer, M.; Lin, B.; Kingsley, J.; Marsh, P.; Diekmann, L.; Ossola, A. Gardening can relieve human stress and boost nature connection during the COVID-19 pandemic. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 68, 127483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainamani, H.E.; Gumisiriza, N.; Bamwerinde, W.M.; Rukundo, G.Z. Gardening activity and its relationship to mental health: Understudied and untapped in low-and middle-income countries. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 29, 101946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, F.; Hermans, Z.; De Koster, J.; Smismans, R. Promoting pro-environmental gardening practices: Field experimental evidence for the effectiveness of biospheric appeals. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 70, 127544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmonte, Z.J.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Ong, A.K.; Chuenyindee, T.; Yuduang, N.; Kusonwattana, P.; Nadlifatin, R.; Persada, S.F.; Buaphiban, T. How important is the tuition fee during the COVID-19 pandemic in a developing country? evaluation of filipinos’ preferences on public university attributes using conjoint analysis. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, A.K.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Lagura, F.C.; Ramos, R.N.; Salazar, J.M.; Sigua, K.M.; Villas, J.A.; Chuenyindee, T.; Nadlifatin, R.; Persada, S.F.; et al. Young Adult Preference Analysis on the attributes of COVID-19 vaccine in the Philippines: A conjoint analysis approach. Public Health Pract. 2022, 4, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Attributes | Levels |

|---|---|

| Types of Succulents | Agavaceae Succulents, Apocynaceae Succulents, Cactaceae Succulents, Crassulaceae Succulents (Appendix A) |

| Succulent Variegation | Variegated, Non-variegated |

| Price | Below PHP 100, PHP 101 to PHP 250, PHP 251 to PHP 400, PHP 401 and above |

| Size of the Succulent (diameter) | 1–3 inches, 4–6 inches, 7–9 inches, more than 9 inches |

| Size of the Pot | 2–4 inches (diameter) to 2–4 inches (height), 5–7 inches (diameter) to 5–7 inches (height), 8–10 inches (diameter) to 8–10 inches (height), 11 and above inches (diameter) to 11 and above inches (height) |

| Material of the Pot | Ceramic, Clay, Plastic |

| Payment Method | Online Payment, On-site Payment |

| Family Name | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Agavaceae Succulents | |

| Apocynaceae Succulents | |

| Cactaceae Succulents | |

| Crassulaceae Succulents |

| Characteristics | Category |

|---|---|

| Gender |

|

| Age |

|

| How many succulents do you have? |

|

| How frequently do you buy succulents in a month? |

|

| Location |

|

| Combinations | Type of Succulent | Succulent Variegation | Price | Size of Succulent | Size of the Pot | Pot Material | Method of Payment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Crassulaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 101 to PHP 250 | More than 9 inches (diameter) | 8–10 in. (diameter) to 8–10 in. (height) | Ceramic | On-site Payment |

| 2 | Crassulaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 101 to PHP 250 | 1 to 3 in. (diameter) | 5–7 in. (diameter) to 5–7 in. (height) | Ceramic | Online Payment |

| 3 | Agavaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 101 to PHP 250 | 7 to 9 in. (diameter) | 11 and above in. (diameter) to 11 and above in. (height) | Plastic | Online Payment |

| 4 | Crassulaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | PHP 251 to PHP 400 | 1 to 3 in. (diameter) | 11 and above in. (diameter) to 11 and above in. (height) | Plastic | On-site Payment |

| 5 | Apocynaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 251 to PHP 400 | 7 to 9 in. (diameter) | 11 and above in. (diameter) to 11 and above in. (height) | Ceramic | Online Payment |

| 6 | Cactaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 401 and above | 1 to 3 in. (diameter) | 8–10 in. (diameter) to 8–10 in. (height) | Clay | On-site Payment |

| 7 | Crassulaceae Succulents | Variegated | Below PHP 100 | 7 to 9 in. (diameter) | 8–10 in. (diameter) to 8–10 in. (height) | Clay | Online Payment |

| 8 | Cactaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | PHP 101 to PHP 250 | More than 9 inches (diameter) | 2–4 in. (diameter) to 2–4 inches (height) | Ceramic | Online Payment |

| 9 | Crassulaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | PHP 401 and above | 4 to 6 in. (diameter) | 11 and above in. (diameter) to 11 and above in. (height) | Ceramic | Online Payment |

| 10 | Agavaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | PHP 251 to PHP 400 | 4 to 6 in. (diameter) | 8–10 in. (diameter) to 8–10 in. (height) | Ceramic | Online Payment |

| 11 | Apocynaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | PHP 101 to PHP 250 | 7 to 9 in. (diameter) | 5–7 in. (diameter) to 5–7 in. (height) | Clay | On-site Payment |

| 12 | Agavaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 251 to PHP 400 | 7 to 9 in. (diameter) | 11 and above in. (diameter) to 11 and above in. (height) | Clay | Online Payment |

| 13 | Agavaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 101 to PHP 250 | 4 to 6 in. (diameter) | 2–4 in. (diameter) to 2–4 inches (height) | Clay | On-site Payment |

| 14 | Cactaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 401 and above | 7 to 9 in. (diameter) | 8–10 in. (diameter) to 8–10 in. (height) | Ceramic | Online Payment |

| 15 | Agavaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | PHP 401 and above | More than 9 inches (diameter) | 5–7 in. (diameter) to 5–7 in. (height) | Plastic | Online Payment |

| 16 | Cactaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 251 to PHP 400 | More than 9 inches (diameter) | 8–10 in. (diameter) to 8–10 in. (height) | Plastic | On-site Payment |

| 17 | Apocynaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 251 to PHP 400 | 4 to 6 in. (diameter) | 2–4 in. (diameter) to 2–4 inches (height) | Ceramic | On-site Payment |

| 18 | Crassulaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | PHP 251 to PHP 400 | More than 9 inches (diameter) | 2–4 in. (diameter) to 2–4 inches (height) | Clay | Online Payment |

| 19 | Cactaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | PHP 101 to PHP 250 | 1 to 3 in. (diameter) | 11 and above in. (diameter) to 11 and above in. (height) | Ceramic | On-site Payment |

| 20 | Cactaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | Below PHP 100 | 7 to 9 in. (diameter) | 2–4 in. (diameter) to 2–4 inches (height) | Plastic | On-site Payment |

| 21 | Crassulaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | PHP 401 and above | 7 to 9 in. (diameter) | 2–4 in. (diameter) to 2–4 inches (height) | Ceramic | On-site Payment |

| 22 | Cactaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 251 to PHP 400 | 1 to 3 in. (diameter) | 5–7 in. (diameter) to 5–7 in. (height) | Clay | Online Payment |

| 23 | Apocynaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 401 and above | 1 to 3 in. (diameter) | 2–4 in. (diameter) to 2–4 inches (height) | Plastic | Online Payment |

| 24 | Agavaceae Succulents | Variegated | Below PHP 100 | More than 9 inches (diameter) | 11 and above in. (diameter) to 11 and above in. (height) | Ceramic | On-site Payment |

| 25 | Cactaceae Succulents | Variegated | Below PHP 100 | 7 to 9 in. (diameter) | 2–4 in. (diameter) to 2–4 inches (height) | Ceramic | On-site Payment |

| 26 | Apocynaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | PHP 101 to PHP 250 | 4 to 6 in. (diameter) | 8–10 in. (diameter) to 8–10 in. (height) | Plastic | Online Payment |

| 27 | Agavaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | PHP 401 and above | 1 to 3 in. (diameter) | 8–10 in. (diameter) to 8–10 in. (height) | Clay | On-site Payment |

| 28 | Apocynaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | Below PHP 100 | 1 to 3 in. (diameter) | 8–10 in. (diameter) to 8–10 in. (height) | Ceramic | On-site Payment |

| 29 | Crassulaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 101 to PHP 250 | 1 to 3 in. (diameter) | 8–10 in. (diameter) to 8–10 in. (height) | Ceramic | Online Payment |

| 30 | Agavaceae Succulents | Variegated | Below PHP 100 | 1 to 3 in. (diameter) | 2–4 in. (diameter) to 2–4 inches (height) | Ceramic | Online Payment |

| 31 | Cactaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | Below PHP 100 | 4 to 6 in. (diameter) | 11 and above in. (diameter) to 11 and above in. (height) | Clay | Online Payment |

| 32 | Cactaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 401 and above | 4 to 6 in. (diameter) | 5–7 in. (diameter) to 5–7 in. (height) | Ceramic | On-site Payment |

| 33 | Crassulaceae Succulents | Variegated | Below PHP 100 | 4 to 6 in. (diameter) | 5–7 in. (diameter) to 5–7 in. (height) | Plastic | On-site Payment |

| 34 | Apocynaceae Succulents | Variegated | PHP 401 and above | More than 9 inches (diameter) | 11 and above in. (diameter) to 11 and above in. (height) | Clay | On-site Payment |

| 35 | Agavaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | PHP 251 to PHP 400 | 7 to 9 in. (diameter) | 5–7 in. (diameter) to 5–7 in. (height) | Ceramic | On-site Payment |

| 36 | Apocynaceae Succulents | Non-variegated | Below PHP 100 | More than 9 inches (diameter) | 5–7 in. (diameter) to 5–7 in. (height) | Ceramic | Online Payment |

| Characteristics | Category | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 52.9% |

| Female | 42% | |

| Others | 5.1% | |

| Age | Below 20 | 7.4% |

| 20 to 30 | 19.6% | |

| 31 to 40 | 24.2% | |

| 41 to 50 | 32.7% | |

| 51 and above | 16.2% | |

| How many succulents do you have? | 5 and below | 21.9% |

| 6 to 10 | 15.9% | |

| 11 to 15 | 15.2% | |

| 16 and above | 47% | |

| How frequently do you buy succulents in a month? | Once a week | 15.3% |

| Twice a week | 70.5% | |

| Thrice a week | 10.4% | |

| Once a month | 3.7% | |

| Location | Region 1 | 2.6% |

| Region 2 | 1.3% | |

| Region 3 | 2.5% | |

| Region 4A | 4% | |

| Region 4B | 1.5% | |

| Region 5 | 2% | |

| CAR | 12.8% | |

| NCR | 59.3% | |

| Region 6 | 1.8% | |

| Region 7 | 1.8% | |

| Region 8 | 1.6% | |

| Region 9 | 1.5% | |

| Region 10 | 1.8% | |

| Region 11 | 1.2% | |

| Region 12 | 1.6% | |

| Region 13 | 1.6% | |

| BARMM | 1.3% |

| Importance Values | Score |

|---|---|

| Type of Succulents | 2.643 |

| Succulent Variegation | 13.947 |

| Price | 34.985 |

| Size of the Succulent (diameter) | 28.423 |

| Size of the Pot | 10.834 |

| Pot Material | 2.883 |

| Method of Payment | 6.285 |

| Attributes | Preference | Utility Estimates | Std. Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Succulents | Agavaceae Succulents | 0.023 | 0.090 |

| Apocynaceae Succulents | −0.047 | 0.090 | |

| Cactaceae Succulents | −0.042 | 0.090 | |

| Crassulaceae Succulents | 0.065 | 0.090 | |

| Succulent Variegation | Variegated | 0.295 | 0.052 |

| Non-variegated | −0.295 | 0.052 | |

| Price | Below PHP 100 | 0.816 | 0.090 |

| PHP 101 to PHP 250 | 0.237 | 0.090 | |

| PHP 251 to PHP 400 | −0.390 | 0.090 | |

| PHP 401 and above | −0.663 | 0.090 | |

| Size of the Succulent (diameter) | 1 to 3 inches | −0.864 | 0.090 |

| 4 to 6 inches | 0.221 | 0.090 | |

| 7 to 9 inches | 0.306 | 0.090 | |

| More than 9 inches | 0.337 | 0.090 | |

| Size of the Pot | 2–4 inches (diameter) to 2–4 inches (height) | −0.278 | 0.090 |

| 5–7 inches (diameter) to 5–7 inches (height) | −0.039 | 0.090 | |

| 8–10 inches (diameter) to 8–10 inches (height) | 0.138 | 0.090 | |

| 11 and above inches (diameter) to 11 and above inches (height) | 0.179 | 0.090 | |

| Pot Material | Ceramic | 0.045 | 0.069 |

| Clay | −0.077 | 0.081 | |

| Plastic | 0.033 | 0.081 | |

| Method of Payment | Online Payment | 0.133 | 0.052 |

| On-site Payment | −0.133 | 0.052 | |

| (Constant) | 4.806 | 0.055 | |

| Value | Significance | |

|---|---|---|

| Pearson’s R | 0.973 | 0.000 |

| Kendall’s Tau | 0.863 | 0.000 |

| Kendall’s Tau for Holdouts | 1.000 | 0.021 |

| Type of Customer | Description | Value-Adding Services |

|---|---|---|

| High-Value Customer |

|

|

| Core-Value Customer |

|

|

| Lower-Value Customer |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ong, A.K.S.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; De Leon, L.A.S.; Ayuwati, I.D.; Nadlifatin, R.; Persada, S.F. Plantitas/Plantitos Preference Analysis on Succulents Attributes and Its Market Segmentation: Integrating Conjoint Analysis and K-means Clustering for Gardening Marketing Strategy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416718

Ong AKS, Prasetyo YT, De Leon LAS, Ayuwati ID, Nadlifatin R, Persada SF. Plantitas/Plantitos Preference Analysis on Succulents Attributes and Its Market Segmentation: Integrating Conjoint Analysis and K-means Clustering for Gardening Marketing Strategy. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416718

Chicago/Turabian StyleOng, Ardvin Kester S., Yogi Tri Prasetyo, Lance Albert S. De Leon, Irene Dyah Ayuwati, Reny Nadlifatin, and Satria Fadil Persada. 2022. "Plantitas/Plantitos Preference Analysis on Succulents Attributes and Its Market Segmentation: Integrating Conjoint Analysis and K-means Clustering for Gardening Marketing Strategy" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416718

APA StyleOng, A. K. S., Prasetyo, Y. T., De Leon, L. A. S., Ayuwati, I. D., Nadlifatin, R., & Persada, S. F. (2022). Plantitas/Plantitos Preference Analysis on Succulents Attributes and Its Market Segmentation: Integrating Conjoint Analysis and K-means Clustering for Gardening Marketing Strategy. Sustainability, 14(24), 16718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416718