The Effects of Chinese Consumers’ Brand Green Stereotypes on Purchasing Intention toward Upcycled Clothing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- To examine if consumers’ brand stereotypes will influence consumers’ trust, and further affect purchasing intention;

- To develop targeted dimensions of brand green stereotypes, aimed at the fashion industry;

- To explore the moderating mechanism of consumers’ characteristics.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Fashion Green Consumer Behavior

| Author | Antecedent(s) | Mediator(s), Moderator(s) * and Control Variable(s) ** | Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Karen et al. [21] | Fashion involvement, pro-environment attitudes | Adoption of sustainable fashion | |

| D’Souza et al. [22] | Environmental concern, sustainable commitment, pricing, quality, brand image, labeling, faith in others, perceived effectiveness | Personal income and age ** | Purchase intention |

| Visser et al. [23] | Benefit, sustainability image | Fashion image | Behavior intention |

| Ha and Kwon [24] | Past recycling behavior | Environmental concern, anticipated guilt * | Green apparel shopping behavior |

| Wei and Jung [25] | Product value, green value | Face-saving *, altruism and egoism ** | Purchase intention |

| Wiederhold and Martinez [14] | Image, price, lack of information, availability, transparency, consumption habits inertia | / | Intention behavior gap |

| Song and Kim [26] | Societal benefit, personal benefit | Altruistic/egoistic warmth | Purchase intention |

| Diddi et al. [27] | Perceived value, sustainability commitment, uniqueness, lifestyle changes and so on | Intention-behavior gap | |

| Park and Lin [28] | Risk, utilitarian value, self-expressiveness, environmental concern and so on | Purchase intention/experience | |

| Grazzini et al. [29] | Study1: Sustainable product attributes Study2: Implicit association test Study3: Sustainable product attributes | Study 3: perceived warmth | Purchase intention |

| Kong et al. [30] | Sustainability perception (cultural, economic, environment, social) | Brand attitude, luxury *, trust * | Buying behavior |

| Neumann et al. [31] | Social responsibility | Trust, attitude, perceived effectiveness | Purchase intention |

| Dhir et al. [32] | Environmental knowledge, green trust, environmental concern and so on | Environmental attitude, age *, gender * | Buying behavior |

| Kumar et al. [33] | Environmental concern | Attitude, subjective norm, personal moral norms | Purchase intention |

| Ashaduzzaman [34] | Trust, attitude, environment responsibility, subjective norm, emotional value and so on | Perceived usefulness | Collaborative consumption |

| Hasbullah et al. [35] | Motivation, opportunity, ability | Fashion consciousness * | Purchase intention |

| Hasan et al. [36] | Environmental concerns, attitude, fashionable products, product performance and so on | Willingness to purchase organic cotton clothing | |

| Chen et al. [37] | Fashion brand image | Customer participation behavior, brand experience, brand trust *, participation * | Brand loyalty |

2.2. Band Stereotype and Brand Image

| Author | Dimensions, Moderator(s) * | Mediator(s) | Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bauer et al. [51] | Warmth, competence Brand style * | Perceived fit, attitude | Purchase intention Brand response |

| Japutra et al. [52] | Aesthetic benefit Self-expressiveness benefit | Warmth stereotype Competence stereotype | Relationship quality (satisfaction, trust, affective favorability, and so on) |

| Kolbl et al. [53] | Warmth, competence | Brand identification | Purchase intention |

| Kolbl et al. [54] | Warmth, competence | Perceived value | Purchase intention |

| Gidakovic et al. [44] | Origin/brand/user warmth, competence | Perceived value | Purchase intention |

| Diamantopoulos et al. [45] | Warmth, competence | Attitudinal response | Purchase intention |

| Japutra et al. [55] | Cognitive/affective components | Warmth, competence | Brand attachment |

| Gong et al. [56] | Green brand positioning | Warmth, competence | Consumer response |

| Wang et al. [57] | Warmth, competence | Country-of-origin image | Purchase intention |

2.3. Consumer–Brand Relationship

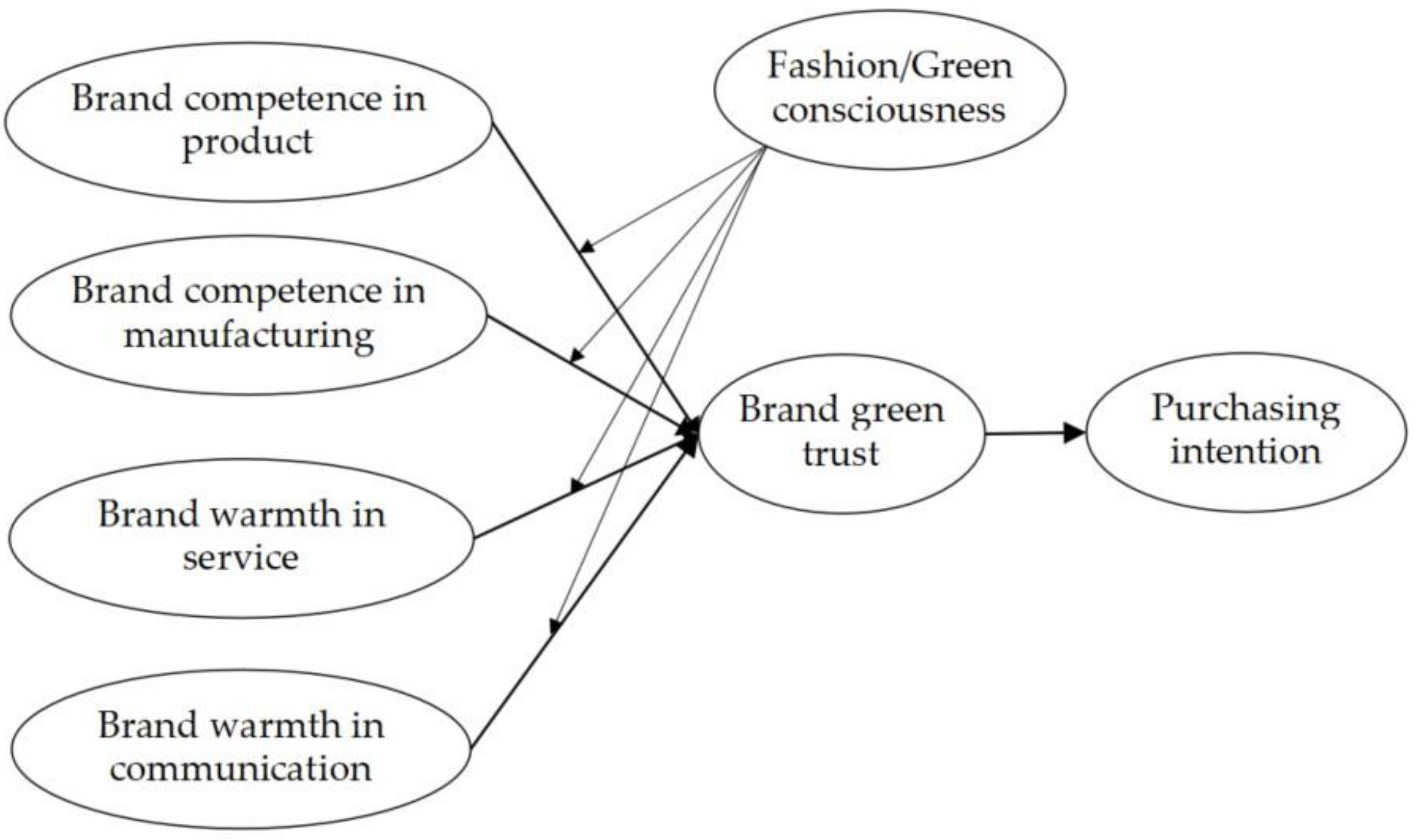

3. Grounded Theorizing and Research Model

3.1. Procedure and Sample

3.2. Open Coding and Axial Coding

3.3. Selective Coding

3.4. Research Hypotheses and Model

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Collection and Sample

- Gender: 38.4% male and 61.6% female.

- Age: post-1990s (born after 1990) accounts for 57.3%, followed by post-1980s (born after 1980), accounting for 27.0%. These two groups accounted for nearly 80% of the total sample.

- Income: the monthly disposable income is CNY 4001–7000, accounting for 40.7%, followed by CNY 7001–10,000, accounting for 33.6%.

- Occupation: most of them are corporate staff, accounting for 69.3%, followed by students (20.9%), government workers (5.9%), freelancers and others (3.9%).

- Regions: East China (30.7%), South China (28.9%), North China (17.0%), Central and West China (13.2%), Northeast China (10.2).

4.2. Measures and Measurement Model

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Results of the Structural Model

5.2. Results of Mediating Effect Test

5.3. Results of Multi-Group Analysis

6. Conclusions, Suggestions, and Limitations

- Brand green stereotype positively relates to green trust and further significantly affects purchase intentions on upcycled fabric clothing, particularly competence in product and warmth in service. Consumers’ perceptions of the brand (product, production, service, and communication) affect their relationship quality, such as trust, with brands. The entrenched image of fashion brands makes consumers distrustful of their steadfast commitment to sustainability. These results partly explain why consumers are reluctant to buy green clothing when they have an eco-friendly attitude and promote sustainable lifestyles. It would seem that products and services are currently the top priorities for fashion brands to embed environmental elements in their brand image.

- This study demonstrates that the relationships between purchase intention and two determinants, brand competence and brand warmth, are mediated by brand green trust. In the relatively new market of upcycled fabric clothing, building consumer trust in the brand can be an effective way to avoid the risks associated with information asymmetry and consumer skepticism about greenwashing of fashion brands.

- This study indicates that green consciousness enhances the effect of brand green stereotypes on brand trust in products and manufacturing without significantly moderating the effect between brand warmth and trust. Green consciousness can offset the negative impact of consumers’ concerns about the high price and the safety of recycled fabrics to some extent.

- Contrary to the predictions, fashion consciousness, a moderating factor, actually enhanced the spillover of brand green stereotypes in service and weakened the effect of communication dimension. In contrast to previous research that concluded that fashion consciousness negatively affects sustainable behavior, such as secondhand clothing, fashion consciousness is regarded as an innovative and acceptable product by many fashionable consumers. Fashionable consumers attach great importance to brand warmth in actual service because of the lower likelihood of greenwashing behavior. Conversely, the perception of the green image in communication is crucial for consumers with low fashion awareness. It is more likely that these consumers are fashion followers rather than fashion leaders, and their purchase intention is influenced more by how information is communicated and marketed.

- Brand strategies positioning. Fashion brands can apply the scales of brand green stereotype to evaluate their positioning relative to competitors in brand positioning, high warmth–high capability, high warmth–low capability, low warmth–high capability, and low warmth–low capability, to adjust their brand strategies.

- Green marketing mix. Fashion brands can incorporate green image construction throughout the branding process, including products, manufacturing, services, and communication. It is possible for fashion brands, for example, to develop products that are more fashionable, functional, and comfortable during the product development process. Social media content may also be more specific concerning green manufacturing and products. The company will be providing more green services by offering reusable bags, more convenient recycling channels for used clothes, and trade-in programs.

- Targeted consumer segmentation. In terms of market segmentation, fashion brands can develop different marketing strategies. For fast fashion brands or brands with short product life cycles, it is recommended to focus on continuous services, such as offering reusable bags, more convenient recycling channels for used clothes, and trade-in offers, to enhance fashionable consumers’ trust. For brands whose target consumers are less fashionable, communication strategy is essential, such as providing specific product information, green philosophy, and the recommendation of new products of upcycled fabric clothing.

- Enhancement of consumers’ green consciousness. To cultivate consumers’ green consciousness, the brand can guide customers to transform from mere sales contributors to environmental guardians, such as providing specific product introductions and endorsements from suppliers, specialists, and authorities.

- According to prior studies, the influence of consumers’ buying intention on green products depends on product type. Therefore, when the product type changes, the brand stereotype’s dimensions may also change. This is the reason that we adopted the grounded theory approach to develop scales of brand stereotypes to improve the practical significance of the conclusion. Different research objectives may broaden understanding of brand image, such as social dimension, because more young people regard green behavior as a fashion and are willing to share their thoughts and actions on social media.

- Relationship quality has been confirmed as a vital mediation between consumers and brands and a practical approach to reducing consumers’ uncertainties. Since greenwashing is very common in the apparel industry and seriously affects consumers’ trust in the green practices of fashion brands, we chose to use trust as a crucial factor. Regarding illustrating the relationship between brand stereotype and consumer behavior, commitment, social benefit, and affective favorability are valuable relationship qualities. Therefore, further study is needed to explore more relationship qualities’ effects on buying intention.

- Although green and fashion consciousness are regarded as two crucial variables of consumer characteristics, other individual characteristics can be considered, such as empathic concern, hedonism, and frugality [83]. Thus, it would be interesting to explore how upcycled clothing perception and brand green attitudes differ by different segmentation consumers.

- Finally, due to the variety of clothing, product-related factors (e.g., price) require attention in further sustainable fashion research to obtain more meaningful and targeted conclusions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leonas, K.K. The use of recycle fibres in fashion and home products. In Textiles and Clothing Sustainability; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan, S. Denim recycling. In Textiles and Clothing Sustainability; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 79–124. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.L.C.; Henninger, C.E.; Apeagyei, P.J.; Tyler, D. Determining effective sustainable fashion communication strategies. In Sustainability in Fashion; Henninger, C.E., Apeagyei, P.J., Goworek, H., Ryding, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Chambrige, UK, 2017; pp. 127–149. [Google Scholar]

- Kotahwala, K. The Psychology of sustainable consumption. Prog. Brain Res. 2020, 253, 283–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gullingsrud, A.; Perkkins, L. Designing for the circular economy: Cradle to Cradle® design. In Sustainable Fashion What’s Next? Hethorn, J., Ulasewicz, C., Eds.; Bloomsbury: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 292–312. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich, D. Comparative analysis of sustainability measures in the apparel industry: An empirical consumer and market study in Germany. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Lee, J. The effects of consumers’ perceived values on intention to purchase upcycled products. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A.; Kautish, P. Antecedents to green apparel purchase behavior of Indian consumers. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2021, 31, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcooy, L.; Wang, Y.T.; Chi, T. Why is collaborative apparel consumption gaining popularity? An empirical study of US gen Z consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobuj, M.; Khan, A.M.; Habib, M.A.; Islam, M.M. Factors influencing eco-friendly apparel purchase behavior of Bangladeshi young consumers: Case study. Res. J. Text. Appar. 2021, 25, 139–157. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, F.; Jung, H.J.; OH, K.W. Motivators and barriers for buying intention of upcycled fashion products in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2584. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Su, S.; Zhou, L.; Liu, X. Attitude toward the viral ad: Expanding traditional advertising models to interactive advertising. J. Interact. Mark. 2013, 27, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, M.; Martinez, L.F. Ethical consumer behaviour in Germany: The attitude-behaviour gap in the green apparel industry. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Sethia, N.K.; Srinivas, S. Mindful consumption: A customer-centric approach to sustainability. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namhee, L.; Yun, J.C.; Chorong, Y.; Yuri, L. Does green fashion retailing make consumers more eco-friendly?: The influence of green fashion products and campaigns on green consciousness and behavior. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2012, 30, 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, D.; McMaster, R.; Newholm, T. Care and commitment in ethical consumption: An exploration of the “attitude-behaviour gap”. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Jaworski, B.J.; Maclnnis, D.J. Strategic brand concept-image management. J. Mark. 1986, 50, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.L. It’s not easy being green: The effects of attribute tradeoffs on green product preference and choice. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J.; Valenzuela, A. Brands as signals: A cross-country validation study. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karen, K.M.; Charlotte, S.L.; Elita, Y.L.; Jimmy, M.T.C. Popularization of sustainable fashion: Barriers and solutions. J. Text. Inst. 2015, 106, 939–952. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, C.; Gilmore, A.J.; Hartmann, P.; Ibáñez, V.A.; Sullivan-Mort, G. Male eco-fashion: A market reality. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.; Gattol, V.; Helm, R.V.D. Communicating sustainable shoes to mainstream consumers: The impact of advertisement design on buying intention. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8420–8436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ha, S.; Kwon, S. Spillover from past recycling to green apparel shopping behavior: The role of environmental concern and anticipated guilt. Fash. Text. 2016, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, X.; Jung, S. Understanding Chinese consumers’ intention to purchase sustainable fashion products: The moderating role of face-saving orientation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, S.Y.; Kim, Y.K. Doing good better: Impure altruism in green apparel advertising. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diddi, S.; Yan, R.T.; Bloodhart, B.; Bajtelsmit, V.L.; Mcshane, K. Exploring young adult consumers’ sustainable clothing consumption intention-behavior gap: A Behavioral Reasoning Theory perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 18, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L. Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazzini, L.; Acuti, D.; Aiello, G. Solving the puzzle of sustainable fashion consumption: The role of consumers’ implicit attitudes and perceived warmth. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.M.; Witmaier, A.; Ko, E. Sustainability and social media communication: How consumers respond to marketing efforts of luxury and non-luxury fashion brands. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, H.L.; Martinez, L.M.; Martinez, L.F. Sustainability efforts in the fast fashion industry: Consumer perception, trust and purchase intention. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2021, 12, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Sadiq, M.; Talwar, S.; Sakashita, M.; Kaur, P. Why do retail consumers buy green apparel? A knowledge-attitude-behaviour-context perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Garg, P.; Singh, S. Pro-environmental purchase intention towards eco-friendly apparel: Augmenting the theory of planned behavior with perceived consumer effectiveness and environmental concern. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2022, 13, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaduzzaman, M.; Jebarajakirthy, C.; Weaven, S.K.; Maseeh, H.I.; Das, M.; Pentecost, R. Predicting collaborative consumption behaviour: A meta-analytic path analysis on the theory of planned behaviour. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 968–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbullah, N.N.; Sulaiman, Z.; Mas’od, A.; Ahmad Sugiran, H.S. Drivers of sustainable apparel purchase intention: An empirical study of Malaysian millennial consumers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Cai, L.; Ji, X.; Ocran, F.M. Eco-friendly clothing market: A study of willingness to purchase organic cotton clothing in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Halepoto, H.; Liu, C.; Yan, X.; Qiu, L. Research on influencing mechanism of fashion brand image value creation based on consumer value co-creation and experiential value perception theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G.; Banaji, M.R. Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 102, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervyn, N.; Fiske, S.T.; Malone, C. Brands as intentional agents framework: How perceived intentions and ability can map brand perception. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fournier, S. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L.; Garbinsky, E.N.; Vohs, K. Cultivating admiration in brands: Warmth, competence, and landing in the “golden quadrant. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivens, B.S.; Leischnig, A.; Muller, B.; Valta, B. On the role of brand stereotypes in shaping consumer response toward brands: An empirical examination of direct and mediating effects of warmth and competence. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 808–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riefler, P. Why consumers do (not) like global brands: The role of globalization attitude, GCO and global brand origin. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidaković, P.; Szőcs, I.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Florack, A.; Egger, M.; Žabkar, V. The interplay of brand, brand origin and brand user stereotypes in forming value perceptions. Brit. J. Manag. 2022, 33, 1924–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Szőcs, I.; Florack, A.; Kolbl, Ž.; Egger, M. The bond between country and brand stereotypes: Insights on the role of brand typicality and utilitarian/hedonic nature in enhancing stereotype content transfer. Int. Mark. Rev. 2021, 38, 1143–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Benson-Rea, M. Country of origin branding: An integrative perspective. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Cuddy, A.J.; Glick, P.; Xu, J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuddy, A.J.C.; Fiske, S.T.; Glick, P. Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 40, 61–149. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy, A.J.; Glick, P.; Beninger, A. The dynamics of warmth and competence judgments, and their outcomes in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2011, 31, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S.; Alvarez, C. Brands as relationship partners: Warmth, competence, and in-between. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, B.C.; Johnson, C.D.; Singh, N. Place–brand stereotypes: Does stereotype-consistent messaging matter? J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2018, 27, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japutra, A.; Molinillo, S.; Wang, S. Aesthetic or self-expressiveness? Linking brand logo benefits, brand stereotypes and relationship quality. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbl, Ž.; Arslanagić-Kalajdžić, M.; Diamantopoulos, A. Stereotyping global brands: Is warmth more important than competence? J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbl, Ž.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Arslanagić-Kalajdžić, M.; Zabkar, V. Do brand warmth and brand competence add value to consumers? A stereotyping perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 118, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japutra, A.; Molinillo, S.; Ekinci, Y. Do stereotypes matter for brand attachment? Mark. Intell. Plan. 2021, 39, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Sheng, G.; Peverelli, P.; Dai, J. Green branding effects on consumer response: Examining a brand stereotype-based mechanism. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021, 30, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shen, X.D.; Yan, L. The impact of national stereotypes towards country-of-origin images on purchase intention: Empirical evidence from countries of the Belt and Road initiative. J. Asian Financ. Econ. 2022, 9, 409–422. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, S.K.; Ahearne, M.; Hu, Y.; Schillewaert, N. Resistance to brand switching when a radically new brand is introduced: A social identity theory perspective. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L.A.; Evans, K.R.; Cowles, D. Relationship quality in services selling: An interpersonal influence perspective. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D. Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grégoire, Y.; Tripp, T.M.; Legoux, R. When customer love turns into lasting hate: The effects of relationship strength and time on customer revenge and avoidance. J. Mark. 2009, 273, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, H.; Leung, A.; Yan, R.N. It is nice to be important, but it is more important to be nice: Country-of-origin’s perceived warmth in product failures. J. Consum. Behav. 2013, 12, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.P.; Weng, J.C.M.; Hsieh, Y.C. Relational bonds and customer’s trust and commitment—A study on the moderating effects of web site usage. Serv. Ind. J. 2003, 23, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. The drivers of green brand equity: Green brand image, green satisfaction, and green trust. J. Busi. Ethics 2010, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulding, C. Grounded theory, ethnography and phenomenology: A comparative analysis of three qualitative strategies for marketing research. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spiggle, S. Analysis and interpretations of qualitative data in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.; Vohs, K.D.; Mogilner, C. Nonprofits are seen as warm and for-profits as competent: Firm stereotypes matter. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.S.; Choe, J.Y.J.; Petrick, J.F. The effect of celebrity on brand awareness, perceived quality, brand image, brand loyalty, and destination attachment to a literary festival. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Japutra, A. Building enduring culture involvement, destination identification and destination loyalty through need fulfillment. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 47, 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Punyatoya, P. Linking environmental awareness and perceived brand eco-friendliness to brand trust and purchase intention. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2014, 15, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Kim, J. Effects of brand personality on brand trust and brand affect. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 639–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, B. From virtual community members to C2C e-commercebuyers: Trust in virtual communities and its effect on consumers’ purchase intention. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, A.E.; White, T.B.; Lloyd, S.M. Converting web site visitors into buyers: How web site investment increases consumer trusting beliefs and online purchase intentions. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalafatis, S.P.; Pollard, M. Green marketing and Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour: A cross-market examination. J. Consum. Mark. 1999, 16, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Niehm, N.S.; Jeong, M. Psychographic characteristics affecting behavioral intentions towards pop-up retail. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2010, 38, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gam, H.J. Are fashion-conscious consumers more likely to adopt eco-friendly clothing? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2011, 15, 178–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ziao, C.; McCright, A.M. Gender differences in environmental concern: Revisiting the institutional trust hypothesis in the USA. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, S. How does environmental concern influence specific environmentally related behaviors? A new answer to an old question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaton, K.; Pookulangara, S.A. Collaborative consumption: An investigation into the secondary sneaker market. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 14, 13744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.S.; Hamlin, R.P.; McQueen, R.H.; Degenstein, L.M.; Garrett, T.C.; Dunn, L.A.; Wakes, S.J. Fashion sensitive young consumers and fashion garment repair: Emotional connections to garments as a sustainability strategy. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, S.; Lee, S.H. One size fits all? Segmenting consumers to predict sustainable fashion behavior. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2022, 26, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First-Order Concepts | Second-Order Themes | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| This brand is capable of: | Competence in product (CP) | Brand competence |

| Design: developing fabrics in a variety of colors and textures. | ||

| Performance: developing anti-bacterial, anti-static, anti-radiation, or quick-drying fabrics. | ||

| Durability: developing fabrics that do not fade, shrink, or wrinkle easily. | ||

| Feeling: developing fabrics that feel similar to silk, cotton, or leather. | ||

| Raw materials: using mainly recycled or sustainable production materials. | Competence in manufacturing (CM) | |

| Selection of solvents: using nonpolluting, recyclable, and nontoxic solvents. | ||

| Processing: ensuring low pollution (water, soil, air, etc.) in the process. | ||

| Finished product: developing upcycled fabrics that completely degrade in the natural environment. | ||

| I feel the warmth that this brand offers: | Warmth in service (WS) | Brand warmth |

| Package: eco-friendly or recycling shopping bags. | ||

| Recycling channel: a recycling channel for used clothes. | ||

| After-sales: a clothing repair service. | ||

| Recycling service: a convenient recycling service. | ||

| Product information: practical and concrete green product messages rather than abstract feelings. | Warmth in communication (WC) | |

| Ads theme: green theme/environmental-related ads. | ||

| Campaign: marketing campaigns promoting green consumption. | ||

| Ads style: sincere advertising close to the nature. | ||

| I trust this brand is honest and there will be no greenwashing. | Brand green trust (BT) | Relationship quality |

| I trust this brand is using safe upcycled fabrics. | ||

| I trust this brand is employing green practices not motivated by raising the price. | ||

| I believe people’s unrestrained use of natural resources will destroy the balance of the environment. | Green consciousness (GC) | Consumer characteristics |

| I am willing to protect the environment by buying green products. | ||

| I would like to try new products to present my uniqueness. | Fashion consciousness (FC) | |

| Keeping pace with the fashion trend is very important to me. | ||

| I would like to buy upcycled fabric clothing. | Purchasing intention (PI) | Purchasing intention |

| I would like to wear upcycled fabric clothing. |

| Variables and Items | Cronbach’s | CR | AVE | SR | FL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This brand is capable of developing: | 0.833 | 0.834 | 0.558 | 0.747 | |

| Eco-friendly fabrics in a variety of colors or textures. | 0.795 | ||||

| Antibacterial, antistatic, antiradiation, or quick-drying fabrics. | 0.703 | ||||

| Eco-friendly fabrics that do not fade, shrink, or wrinkle easily. | 0.773 | ||||

| Eco-friendly fabrics that feel similar to silk, cotton, or other natural fabrics. | 0.713 | ||||

| This brand is capable of: | 0.851 | 0.852 | 0.591 | 0.769 | |

| Using mainly recycled or sustainable production materials. | 0.771 | ||||

| Using nonpolluting, recyclable, and nontoxic solvents. | 0.726 | ||||

| Ensuring low pollution (water, soil, air, etc.) in the process. | 0.837 | ||||

| Developing upcycled fabrics that degrade in the natural environment. | 0.737 | ||||

| I feel the warmth that this brand offers: | 0.861 | 0.861 | 0.609 | 0.780 | |

| Eco-friendly or recycling shopping bags. | 0.774 | ||||

| A recycling channel for used clothes. | 0.791 | ||||

| A clothing repair service. | 0.792 | ||||

| A convenient recycling service. | 0.763 | ||||

| I feel the warmth that this brand offers: | 0.867 | 0.808 | 0.621 | 0.788 | |

| Concrete green product messages rather than abstract feelings. | 0.810 | ||||

| Green theme or environmental-related ads. | 0.754 | ||||

| Marketing campaigns promoting green consumption. | 0.780 | ||||

| Sincere advertising close to the nature | 0.808 | ||||

| Brand green trust: | 0.775 | 0.777 | 0.539 | 0.734 | |

| This brand is honest, and there will be no greenwashing. | 0.659 | ||||

| I do not have to worry about the safety of upcycled fabrics. | 0.747 | ||||

| This brand’s green practices are not motivated by raising the price. | 0.790 | ||||

| Fashion consciousness: | 0.751 | 0.757 | 0.510 | 0.714 | |

| It is important to me that my clothes be of the latest style. | 0.763 | ||||

| I will dispose of a garment because it has gone out of fashion. | 0.641 | ||||

| I usually dress for fashion and not for comfort. | 0.733 | ||||

| Green consciousness: | 0.843 | 0.844 | 0.643 | 0.802 | |

| Carefree resource-using can disrupt the environmental balance. | 0.784 | ||||

| I am willing to reduce my consumption to protect the environment. | 0.776 | ||||

| I am very concerned about the environment. | 0.844 | ||||

| Purchasing intention: | 0.888 | 0.888 | 0.727 | 0.852 | |

| I am willing to purchase upcycled fashion products of this brand. | 0.886 | ||||

| I will be willing to use upcycled products of this brand. | 0.820 | ||||

| I am willing to visit this brand’s store that sells upcycled fashion products. | 0.850 |

| Constructs | Mean | Standard Deviation | BCP | BCM | BWS | BWC | BT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCP | 3.623 | 0.744 | |||||

| BCM | 3.691 | 0.778 | 0.511 ** | ||||

| BWS | 3.679 | 0.806 | 0.514 ** | 0.444 ** | |||

| BWC | 3.784 | 0.830 | 0.468 ** | 0.465 ** | 0.521 ** | ||

| BT | 2.916 | 0.879 | 0.278 ** | 0.189 ** | 0.198 ** | 0.260 ** | |

| PI | 3.891 | 0.899 | 0.643 ** | 0.610 ** | 0.632 ** | 0.650 ** | 0.392 ** |

| Path | Beta | SE | Bias-Corrected 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| BCP→BT→PI | 0.163 | 0.064 | 0.065 | 0.276 | 0.004 ** |

| BCM→BT→PI | 0.111 | 0.061 | 0.025 | 0.216 | 0.022 * |

| BWS→BT→PI | 0.156 | 0.066 | 0.051 | 0.276 | 0.012 * |

| BWC→BT→PI | 0.136 | 0.063 | 0.042 | 0.241 | 0.019 * |

| Fashion Consciousness | ∆χ2 | ∆df | p |

| Measurement weights | 10.080 | 14 | 0.756 |

| Structural covariances | 25.185 | 28 | 0.618 |

| Measurement residuals | 41.903 | 48 | 0.720 |

| Green consciousness | ∆χ2 | ∆df | p |

| Measurement weights | 33.673 | 14 | 0.002 ** |

| Structural covariances | 50.604 | 28 | 0.006 ** |

| Measurement residuals | 66.191 | 48 | 0.042 * |

| Path | Fashion Consciousness | Green Consciousness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. (High) | Coeff. (Low) | Coeff. (High) | Coeff. (Low) | |

| BCP→BT | 0.281 | 0.187 | 0.399 *** | 0.052 |

| BCM→BT | 0.156 | 0.121 | 0.401 ** | 0.089 |

| BWS→BT | 0.274 ** | 0.027 | 0.169 | 0.097 |

| BWC→BT | 0.098 | 0.338 ** | 0.109 | 0.188 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pang, C.; Zhou, J.; Ji, X. The Effects of Chinese Consumers’ Brand Green Stereotypes on Purchasing Intention toward Upcycled Clothing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16826. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416826

Pang C, Zhou J, Ji X. The Effects of Chinese Consumers’ Brand Green Stereotypes on Purchasing Intention toward Upcycled Clothing. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16826. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416826

Chicago/Turabian StylePang, Chen, Jie Zhou, and Xiaofen Ji. 2022. "The Effects of Chinese Consumers’ Brand Green Stereotypes on Purchasing Intention toward Upcycled Clothing" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16826. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416826

APA StylePang, C., Zhou, J., & Ji, X. (2022). The Effects of Chinese Consumers’ Brand Green Stereotypes on Purchasing Intention toward Upcycled Clothing. Sustainability, 14(24), 16826. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416826