Sustainability of the Portuguese North-Western Fishing Activity in the Face of the Recently Implemented Maritime Spatial Planning

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

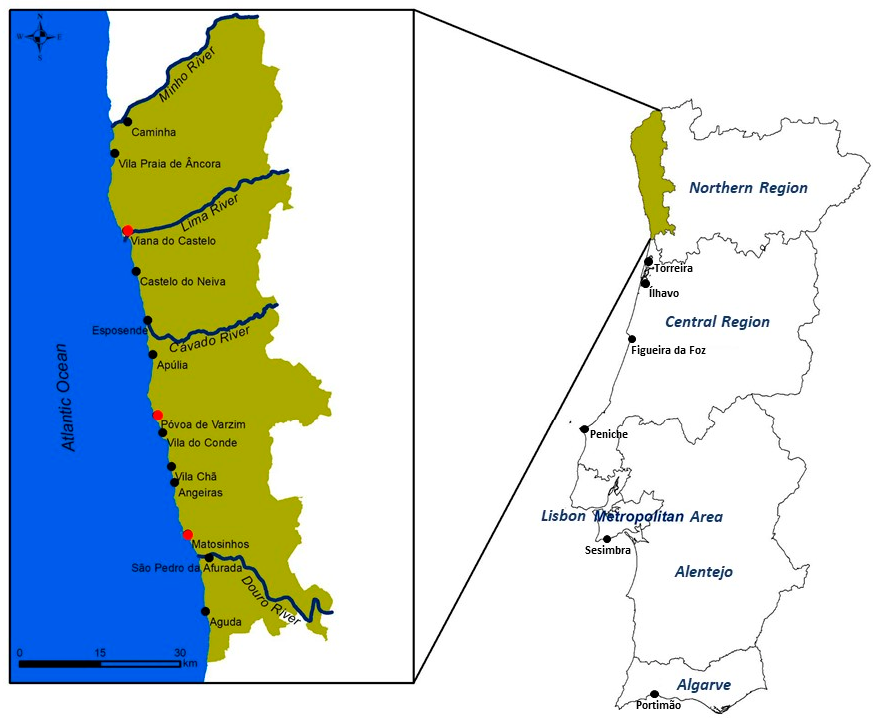

2.1. Description of the Studied Region

2.2. Official Information Sources

2.3. Regional Fishing Trade Network

2.4. Stakeholder Survey

3. Results

3.1. Trend of the Regional Fleet and Fishing Production

3.2. Price Revalorization and Diversification of the Market Offer

3.3. Online Sale Initiative

3.4. Stakeholder Survey

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Report on the Blue Growth Strategy. Towards More Sustainable Growth and Jobs in the Blue Economy. European Commission, Commission Staff Working Document, 61p. 2017. Available online: http://www.bluemed-initiative.eu/blue-growth-strategy-towards0more-sustainable-growth-and-jobs-in-the-blue-economy/ (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- European Commission. Strategic Guidelines for a More Sustainable and Competitive EU Aquaculture for the Period 2021 to 2030. European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, 33p. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2021:236:FIN (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Douvere, F. The importance of marine spatial planning in advancing ecosystem-based sea use management. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, S. Planners to the rescue: Spatial planning facilitating the development of off-shore wind energy. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 60, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, S.E.; Stevens, J.M.; Gentry, R.R.; Kappel, C.V.; Bell, T.W.; Costello, C.J.; Gaines, S.D.; Kiefer, D.A.; Maue, C.C.; Rensel, J.E.; et al. Marine spatial planning makes room for offshore aquaculture in crowded coastal waters. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Payne, I. The Changing Role of Fisheries in Development Policy; Natural Resources Perspectives 59; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pollnac, R.B. Cooperation and conflict between large- and small-scale fisheries: A Southeast Asian example. In Globalization: Effects on Fisheries Resources; Taylor, W.W., Schechter, M.G., Wolfson, L.G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; 15p. [Google Scholar]

- Said, A.; MacMillan, D.; Schembri, M.; Tzanopoulos, J. Fishing in a congested sea: What do marine protected areas imply for the furure of the Maltese artisanal fleet? Appl. Geogr. 2017, 87, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggett, C.; Ten Brink, T.; Russell, A.; Roach, M.; Firestone, J.; Dalton, T.; McCay, B.J. Offshore wind projects and fisheries: Conflict and engagement in the United Kingdom and the United States. Oceanography 2020, 33, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabinyi, M. Dive tourism, fishing and marine protected areas in the Calamianes Islands, Philippines. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECOAST Project. New Methodologies for an Ecosystem Approach to Spatial and Temporal Management of Fisheries and Aquaculture in Coastal Areas. 2019. Available online: https://www.msp-platform.eu/projects/ecoast-new-methodologies-ecosystem-approach-spatial-and-temporal-management-fisheries (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- DGPM, Direção Geral de Política do Mar. National Ocean Strategy 2013–2020. Official Portuguese Report. 112p. 2014. Available online: https://www.dgpm.mm.gov.pt/enm-en (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Salas-Leiton, E.; Vieira, L.R.; Guilhermino, L. Sustainable fishing and aquaculture activities in the Atlantic coast of the Portuguese North Region: Multi-stakeholder views as a tool for maritime spatial planning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGRM, Direção Geral de Recursos Naturais, Segurança e Serviços Marítimos. Plano de Situação. Official Portuguese Report. Espacialização de Servidões, Usos e Atividades. Volumen III-A, 263p. 2018. Available online: https://www.psoem.pt/ (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Percy, J.; O´Riordan, B. The EU common fisheries policy and small-scale fisheries: A forgotten fleet fighting for recognition. In Small-Scale Fisheries in Europe: Status, Resilience and Governance; Pascual-Fernández, J., Pita, C., Bavinck, M., Eds.; MARE Publication Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 23, pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kolding, J.; Béné, C.; Bavinck, M. Small-scale fisheries: Importance, vulnerability and deficient knowledge. In Governance of Marine Fisheries and Biodiversity Conservation: Interaction and Coevolution; Garcia, S.M., Rice, J., Charles, A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Chapter 22; pp. 317–331. [Google Scholar]

- Villasante, S.; Pierce, G.J.; Pita, C.; Pazos, C.; Garcia, J.; Antelo, M.; Da Rocha, J.M.; García, J.; Hastie, L.C.; Veiga, P.; et al. Fisher´s perceptions about the EU discards policy and its economic impact on small-scale fisheries in Galicia (North West Spain). Ecol. Econ. 2016, 130, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasante, S.; Pita, C.; Pierce, G.J.; Pazos, C.; García, J.; Antelo, M.; Da Rocha, J.M.; Garcia, J.; Hastie, L.; Rashid, U.; et al. To land or not to land: How do stakeholders perceive the zero discard policy in European small-scale fisheries? Mar. Policy 2016, 71, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maynou, F.; Gil, M.M.; Vitale, S.; Battista, G.; Foutsi, A.; Rangel, M.; Rainha, R.; Erzini, K.; Gonçalves, J.M.S.; Bentes, L.; et al. Fishers’ perceptions of the European Union discards ban: Perspective from south European fisheries. Mar. Policy 2018, 89, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fauconnet, L.; Frangoudes, K.; Morato, T.; Afonso, P.; Pita, C. Small-scale fishers’ perception of the implementation of the EU landing obligation regulation in the outermost region of the Azores. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 249, 109335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pita, C.; Gaspar, M. Small-scale fisheries in Portugal: Current situation, challenges and opportunities for the future. In Small-Scale Fisheries in Europe: Status, Resilience and Governance; Pascual-Fernández, J., Pita, C., Bavinck, M., Eds.; MARE Publication Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 23, pp. 283–305. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, R.L.; Hobday, A.J.; Allison, E.H.; Armitage, D.; Brooks, K.; Bundy, A.; Cvitanovic, C.; Dickey-Collas, M.; de Miranda Grilli, N.; Gomez, C.; et al. The quilt of sustainable ocean governance: Patterns for practitioners. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 630547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE-DGRM, Instituto Nacional de Estatística–Direção Geral de Recursos Naturais, Segurança e Serviços Marítimos. Estatísticas da Pesca, EP, 2019. Official Portuguese Report. 152p. 2020. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=435690295&PUBLICACOESmodo=2 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- INE-DGRM, Instituto Nacional de Estatística—Direção Geral de Recursos Naturais, Segurança e Serviços Marítimos. Estatísticas da Pesca, EP, 2012. Official Portuguese Report. 135p. 2013. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=153378507&PUBLICACOESmodo=2 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- INE-DGRM, Instituto Nacional de Estatística—Direção Geral de Recursos Naturais, Segurança e Serviços Marítimos. Estatísticas da Pesca, EP, 2013. Official Portuguese Report. 135p. 2014. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=210756920&PUBLICACOESmodo=2 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- INE-DGRM, Instituto Nacional de Estatística—Direção Geral de Recursos Naturais, Segurança e Serviços Marítimos. Estatísticas da Pesca, EP, 2014. Official Portuguese Report. 146p. 2015. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=139431&PUBLICACOESmodo=2 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- INE-DGRM, Instituto Nacional de Estatística—Direção Geral de Recursos Naturais, Segurança e Serviços Marítimos. Estatísticas da Pesca, EP, 2015. Official Portuguese Report. 146p. 2016. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=261842006&PUBLICACOESmodo=2 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- INE-DGRM, Instituto Nacional de Estatística—Direção Geral de Recursos Naturais, Segurança e Serviços Marítimos. Estatísticas da Pesca, EP, 2016. Official Portuguese Report. 152p. 2017. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=277044096&PUBLICACOESmodo=2 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- INE-DGRM, Instituto Nacional de Estatística—Direção Geral de Recursos Naturais, Segurança e Serviços Marítimos. Estatísticas da Pesca, EP, 2017. Official Portuguese Report. 150p. 2018. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=320384843&PUBLICACOESmodo=2 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- INE-DGRM, Instituto Nacional de Estatística—Direção Geral de Recursos Naturais, Segurança e Serviços Marítimos. Estatísticas da Pesca, EP, 2018. Official Portuguese Report. 152p. 2019. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=358627638&PUBLICACOESmodo=2 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- FAO. Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011; 108p. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Green Paper Reform of the Common Fisheries Policy; COM(2009)163 Final; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2009; 27p. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, Y.; Watson, R.A.; Blanchard, J.; Fulton, E.A. Evolution of global marine fishing fleets and the response of fished resources. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 12238–12243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berkow, C. “Too Many Vessels Chase too Few Fish”—Is EU Fishing Overcapacity Really Being Reduced? The Fisheries Secretariat (FishSec): Stockholm, Sweden, 2018; 86p. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, N.; Edwards-Jones, G.; Isidro, E. Defining scale in fisheries: Small versus large-scale fishing operations in the Azores. Fish. Res. 2011, 109, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyader, O.; Berthou, P.; Koutsikopoulos, C.; Alban, F.; Demanèche, S.; Gaspar, M.B.; Eschbaum, R.; Fahy, E.; Tully, O.; Reynal, L.; et al. Small scale fisheries in Europe: A comparative analysis based on a selection of case studies. Fish. Res. 2013, 140, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, D.; Acott, T.G.; Stacey, N.; Urquhart, J. (Eds.) Social Wellbeing and the Values of Small-Scale Fisheries; MARE Publication Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 17, 343p. [Google Scholar]

- ICES, International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. Workshop on the Iberian Sardine Management and Recovery Plan (WKSARMP); ICES Scientific Reports; ICES: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019; Volume 1, 168p. [Google Scholar]

- COTEC Portugal, Associação Empresarial para a Inovação. Blue Growth for Portugal: Uma Visão Empresarial da Economia do mar. Business Report. 368p. 2012. Available online: https://issuu.com/homensdomar/docs/bluegrowthforportugal (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Balqis, A.N.; Ramadhana, L.; Wirawan, R.; Isnainiyah, I.N. Bid-Fish: An android application for online fish auction based on case study from Muara Angke, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Jakarta, Indonesia, 22–23 November 2018; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, P.M.; Laffoley, D. Key elements and steps in the process of developing ecosystem-based marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehler, C.; Douvere, F. Marine Spatial Planning: A Step-by-Step Approach toward Ecosystem-Based Management. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) and the Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB); IOC Manual; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009; pp. 1–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tiller, R.; Richards, R.; Salgado, H.; Strand, H.; Moe, E.; Ellis, J. Assessing stakeholder adaptive capacity to salmon aquaculture in Norway. Consilience: J. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 11, 62–96. [Google Scholar]

| Structural Changes | Organization Changes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | N Vessels | Total Tonnage (GT) | Power (kw) | Vessels Associated to FC 1 (%) |

| 2012 | 1281 | 22107 | 80797 | 77 |

| 2013 | 1260 | 22640 | 82439 | 76 |

| 2014 | 1245 | 22899 | 83997 | 76 |

| 2015 | 1215 | 22360 | 83785 | 85 |

| 2016 | 1176 | 22190 | 83419 | 90 |

| 2017 | 1161 | 21738 | 82230 | 91 |

| 2018 | 1137 | 19788 | 78911 | 92 |

| 2019 | 1131 | 22543 | 83011 | 94 |

| Fishery | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horse Mackerel | Mackerel | Sardine | Octopus | |||||||||

| Nom. Catch (t) | Price (€/kg) | Revalorisat.1 (%) | Nom. Catch (t) | Price (€/kg) | Revalorisat.1 (%) | Nom. Catch (t) | Price (EUR/kg) | Revalorisat.1 (%) | Nom. Catch (t) | Price (EUR/kg) | Revalorisat.1 (%) | |

| 2012 | 3999 | 1.01 | - | 4253 | 0.37 | - | 13,016 | 1.19 | - | 2164 | 3.63 | - |

| 2013 | 3057 | 0.73 | −27.33 | 4741 | 0.30 | −18.97 | 10,029 | 1.19 | −0.15 | 2467 | 2.47 | −32.02 |

| 2014 | 2152 | 0.89 | −11.46 | 2874 | 0.38 | 1.09 | 3699 | 1.76 | 47.78 | 2142 | 3.30 | −8.93 |

| 2015 | 3317 | 0.95 | −6.11 | 3102 | 0.35 | −5.47 | 4570 | 1.79 | 49.85 | 1496 | 3.73 | 2.89 |

| 2016 | 3004 | 0.72 | −28.89 | 3376 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 5630 | 1.59 | 33.29 | 2556 | 3.61 | −0.53 |

| 2017 | 2615 | 0.72 | −28.31 | 2772 | 0.38 | 2.38 | 4143 | 1.54 | 29.19 | 1165 | 5.09 | 40.33 |

| 2018 | 2028 | 1.17 | 16.23 | 6820 | 0.26 | −29.55 | 3004 | 1.95 | 63.39 | 1500 | 6.30 | 73.59 |

| 2019 | 2308 | 1.34 | 32.61 | 1344 | 0.85 | 127.58 | 2753 | 1.84 | 54.17 | 1032 | 5.50 | 51.63 |

| Sales Volume in Online Auction (t) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Matosinhos | Fig. Foz | Peniche | Sesimbra | Portimão | Total |

| 2010 1 | 2.08 | 4.35 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 2.21 | 9.07 |

| 2011 | 1.81 | 0.37 | 15.24 | 4.28 | 7.48 | 29.19 |

| 2012 | 2.15 | 1.26 | 61.06 | 16.09 | 20.94 | 101.51 |

| 2013 | 2.41 | - | 105.33 | 42.13 | 28.93 | 178.80 |

| 2014 | 0.12 | - | 143.54 | 52.69 | 20.46 | 216.82 |

| 2015 | - | - | 156.12 | 63.72 | 8.58 | 228.43 |

| 2016 | 0.45 | 14.51 | 268.25 | 82.10 | 6.01 | 371.33 |

| 2017 | - | 16.21 | 244.11 | 75.74 | 5.28 | 341.34 |

| 2018 | - | 18.67 | 175.72 | 65.69 | 2.94 | 263.02 |

| 2019 | - | 11.95 | 110.43 | 60.80 | 5.55 | 188.74 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salas-Leiton, E.; Costa, A.; Neves, V.; Soares, J.; Bordalo, A.; Costa-Dias, S. Sustainability of the Portuguese North-Western Fishing Activity in the Face of the Recently Implemented Maritime Spatial Planning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031266

Salas-Leiton E, Costa A, Neves V, Soares J, Bordalo A, Costa-Dias S. Sustainability of the Portuguese North-Western Fishing Activity in the Face of the Recently Implemented Maritime Spatial Planning. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031266

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalas-Leiton, Emilio, Ana Costa, Vanessa Neves, Joana Soares, Adriano Bordalo, and Sérgia Costa-Dias. 2022. "Sustainability of the Portuguese North-Western Fishing Activity in the Face of the Recently Implemented Maritime Spatial Planning" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031266