1. Introduction

Urbanization, a process in which people migrate from rural to urban areas, has resulted in a decline of the rural population [

1]. It is primarily the process by which cities expand in size as more people move into major areas to live and work. According to the FAO [

2], two-thirds of the population in the world will be living in cities by 2050. The level of urbanization in Asia is now approximately 50% [

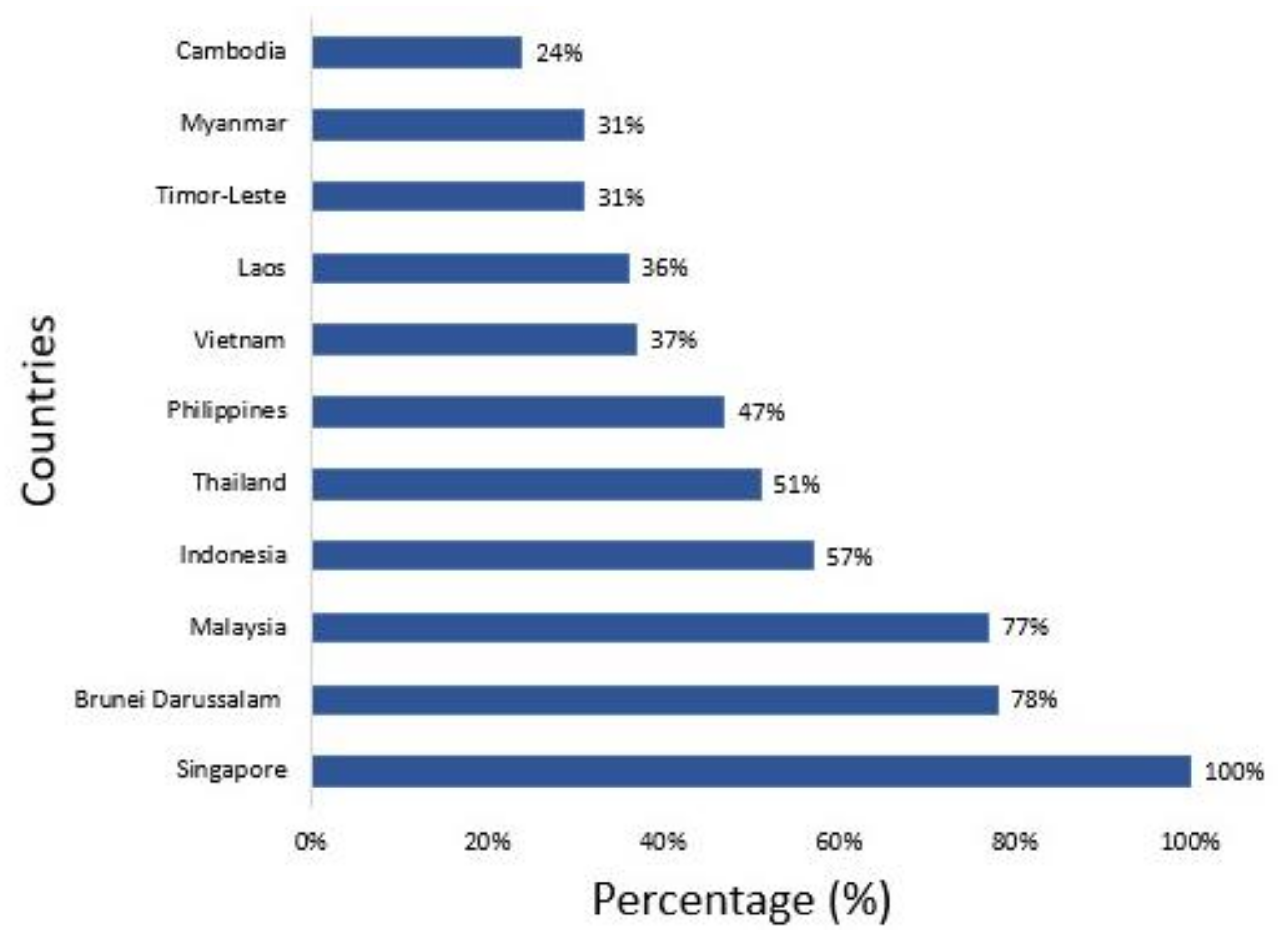

3]. Malaysia, one of the fast-developing countries in the Asia Pacific region, has also become one of the most urbanized developing countries. Therefore, it also faces grave issues relevant to urbanization. The urbanization rate has accelerated, and Malaysia has been listed as the third-highest country (77.2%) with high urbanization rates in Southeast Asia from 2015 to 2020, as shown in

Figure 1.

According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), Malaysia was recorded in an urbanization rate of 80% in 2020 and 85–90% in the next 30 years [

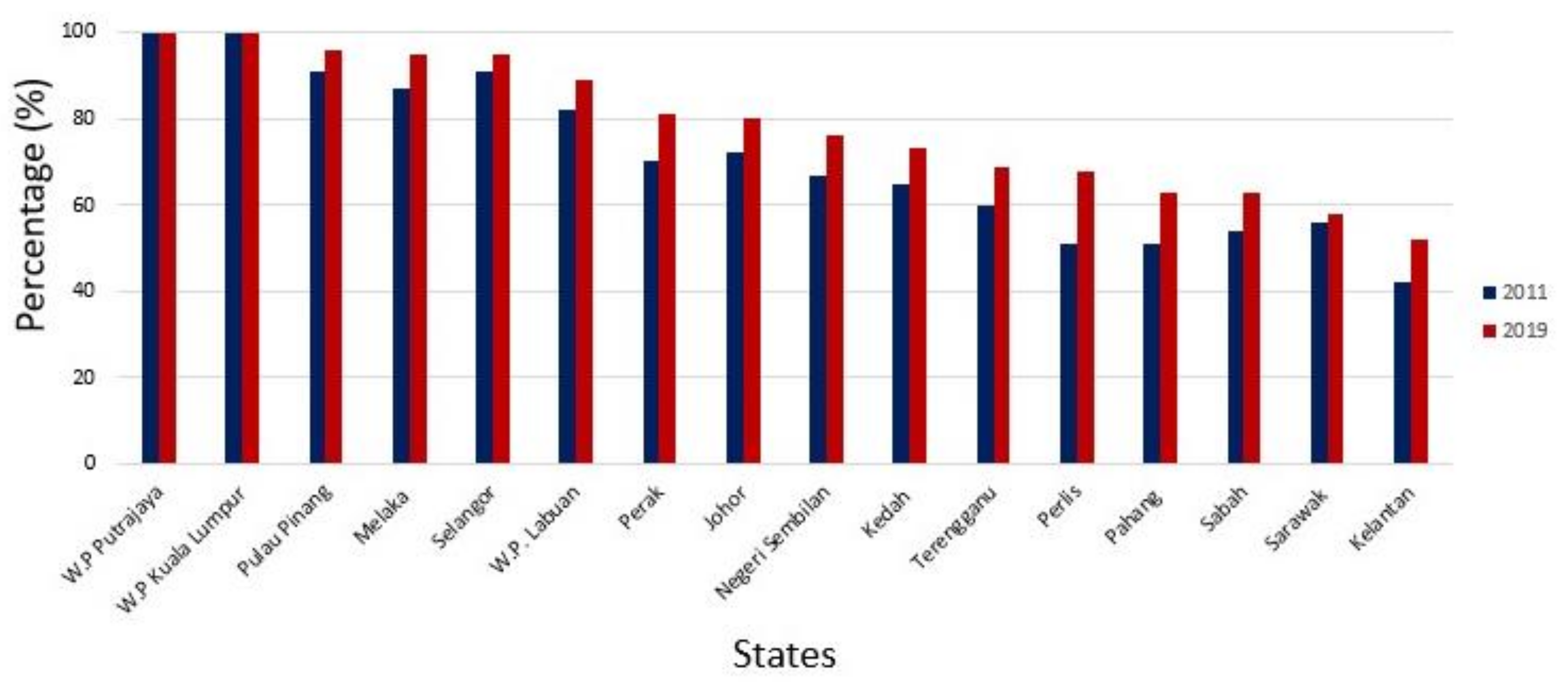

5]. Based on the Malaysia Household Income and Basic Amenities Survey Report [

6], there is a 119.7% urbanized population growth in all states of Malaysia, with the Federal State of Kuala Lumpur (100%), the Federal State of Putrajaya (100%), Selangor (94.5%), and Pulau Pinang (96.2%) holding the highest rates of urbanization (see

Figure 2). Thus, the migration of people from rural to urban regions has resulted in food insecurity, high costs of living, jobless citizens, and urban poverty [

7]. With Malaysia’s increasing urban population, there is growing concern about the cumulative impacts of land fragmentation, resource depletion, higher food costs, increased poverty, increasing unemployment, and urban environmental degradation. As the Malaysian government is committed to ensuring the population’s quality of life and food security, concerted efforts have been made to implement the Urban Agriculture (UA) initiative in Malaysia.

In her past study, Lin et al., (2015) mentioned that numerous cities in developing countries are now encouraging UA in response to issues such as urbanization, food insecurity, and climate change [

8]. UA encompasses activities related to agriculture and agricultural operations in urban areas, and it is a practice of cultivating fruits, grains, root crops, vegetables, herbs, and livestock, which has been practiced by 800 million people worldwide [

9]. Production takes place in rooftops, backyards, community garden spaces, and unused or public places [

2]. The benefits of UA are wide ranging, including improving food security [

10]; generating income [

11]; improving the quality of the urban environment toward sustainability [

12]; and providing job opportunities. Participants involved in UA programs gain direct access to locally produced fresh foods that broaden food diversity while also offering employment opportunities and generating some income through the sale of surplus produce [

13,

14]. Recognition of the positive impacts from UA has led to the development of policies and initiatives that seek to encourage Malaysians to get involved in this activity. The government has established several initiatives and policies to promote the UA program. For instance, the National Agro-food Policy (NAFP) 2011–2020 plays a significant role in serving as a guideline for development of the agricultural sector in Malaysia [

15]. The policy’s objectives are to address domestic and global issues affecting food security in order to assure its sustainability by reforming and transforming the agro-food industry to become more dynamic and fit with urban requirements as enhanced using modern technologies that can be equipped in the limited space available for activities. Accordingly, the UA program has been put under the authority of the Department of Agriculture since 2010 with the name “

Pertanian Bandar”. The purpose of this program is to help urban communities reduce their cost of living through the production of their own food to meet their daily needs and as an additional income for urban communities through the sale of surplus produce [

16].

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a series of measures and goals aimed at eradicating poverty and ensuring the global well-being of human beings [

17]. In line with the SDGs’ main agenda, UA is seen as an advantageous program that contributes to sustainable urban development in terms of providing fresh food supply, especially for low-income families. The SDGs have highlighted the importance of agriculture in sustainable cities, specifically in Target 11, goal 3, which states the need to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable in order to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages”. Thus, all countries should aim to work on enhancing the inclusivity and sustainability of urbanization in order to plan programs that are participatory, integrated, and sustainable for human settlement planning and management in all countries. However, despite the numerous recognized benefits of UA, there are still a number of obstacles preventing it from rapid take-up [

8]. Although UA is no longer an alien term in Malaysia, the employment of UA as an approach to solving urban challenges has not yet received adequate attention as a solution for urban food scarcity. Despite the government’s efforts, there exists a lack of community awareness and participation [

18]. In order to achieve UA’s full potential for social and economic profitability as well as ensure the sustainability of the program, implementation in UA must be participatory. This highlights the fact of why the program’s success is highly contingent upon urban volunteers. Noriah Mat, Senior Deputy Director of Putrajaya Corporation’s Landscape and Parks Development highlighted that community garden programs face a community outreach issue [

19]. As a result, the Community Garden Program’s sustainability has been cast into doubt [

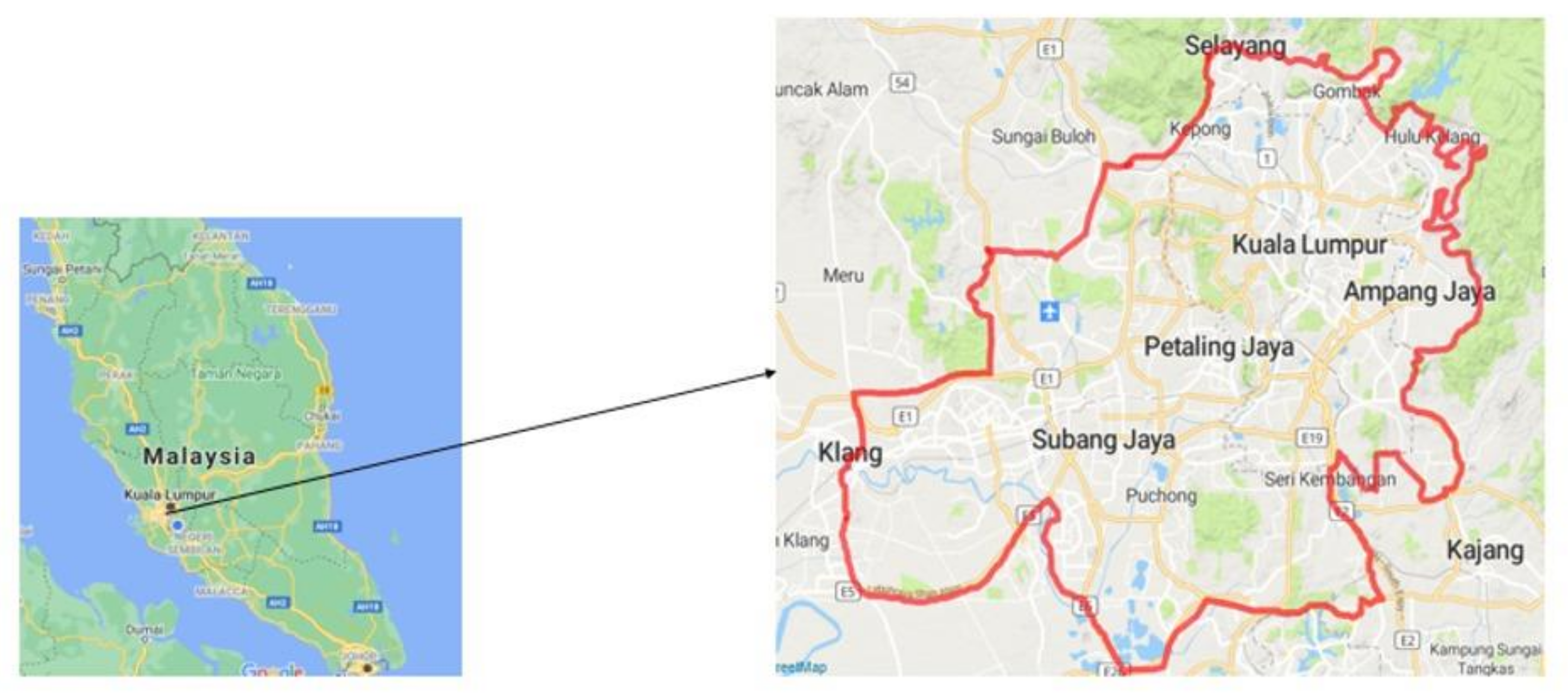

20]. To distinguish UA as a vital element of sustainable urban development, the primary challenge is to develop effective programs that engage urban dwellers and institutions in designing and implementing UA. Given the scarcity of research on this area of study, this project was undertaken to ascertain and comprehend the values that the community of Klang Valley imposes on UA in Malaysia. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to ascertain the assigned and underlying values of UA participation amongst communities that contribute to aspects of community social empowerment in the Klang Valley area of Malaysia.

Past studies have been using the term “empowerment” vaguely without overlooking the probability of additional variables that could enhance the potency of empowerment. There are scarce existing theories that deal independently with UA participants’ empowerment. The theories and models have clarified factors that contribute to empowerment, and the researchers have come up with “participation” as being the main factor influencing empowerment [

21,

22]. To better comprehend its antecedents, the authors unified concepts and variables from dissimilar theoretical frameworks in order to demonstrate that the UA participants’ empowerment has resulted from participation in three dimensions: namely, planning, implementation, and evaluation. Participation is an integral element of social change effort and improvement [

23]. Participation can assist and empower participants and teach them valuable decision making, communication, and research skills while transitioning the program’s structure from a top–down to a collaborative service model [

24]. Previous studies have also mentioned that participation is a medium for empowerment to take place—when people are in a group that is engaged in identifying problems, decision making, and implementing a program, they learn together, develop their confidence and skills, and subsequently contribute to their own development. This notion has been used in many studies related to community programs such as women programs [

25], youth programs [

26], and health programs [

27].

4. Discussion

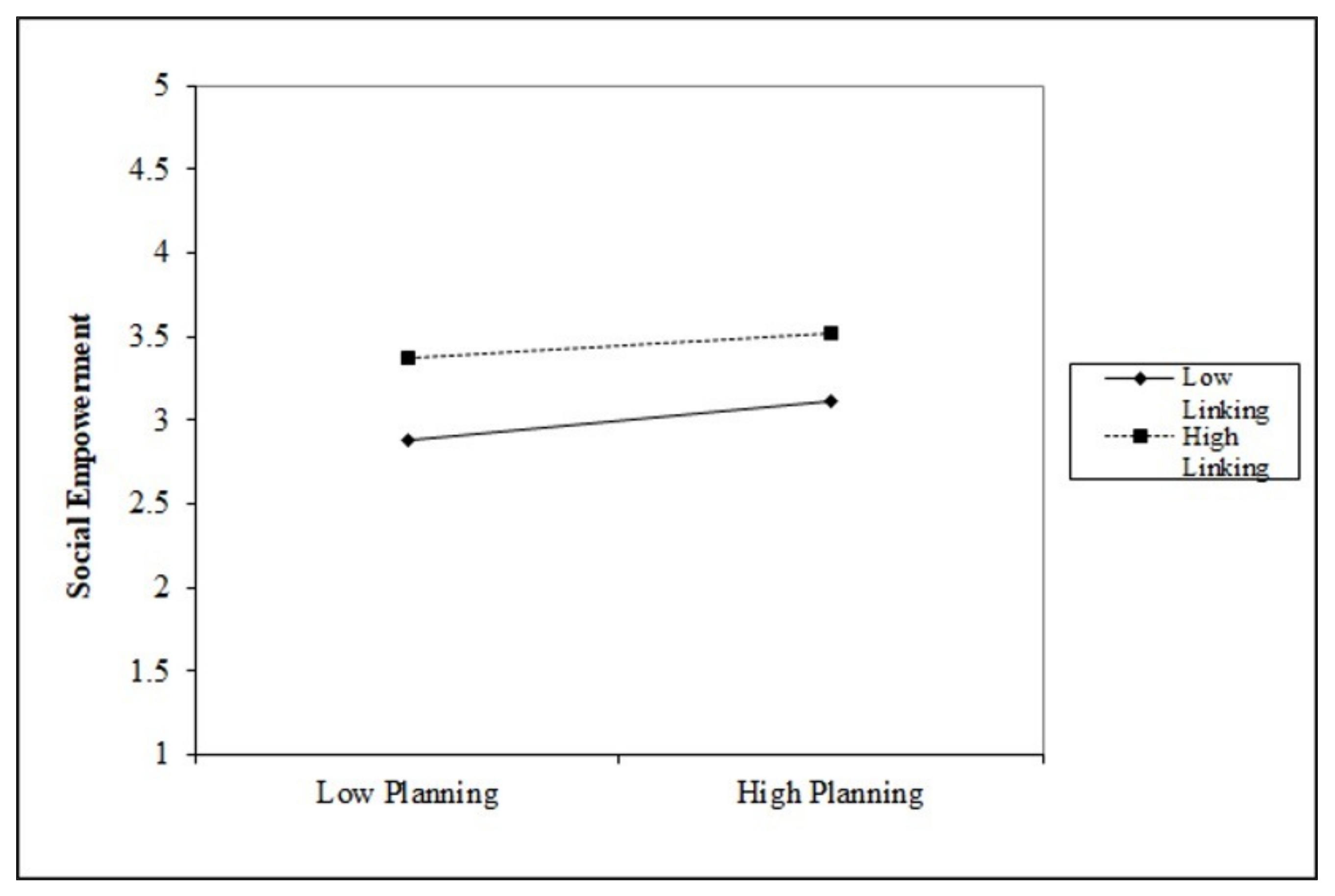

The objective of this study is to explore the direct and indirect effects of predictors on social empowerment. The results generated show no significant relationship between planning and evaluation toward the social empowerment of UA program’s participants. This finding is not surprising, as it is in line with past studies done by Cyril et al., (2015) and Wahdy et al., (2017), which claimed that there is a lack of public involvement at the planning stage in many activities [

58,

59]. A majority of the programs are implemented using the ‘top–down’ approach as opposed to the ‘bottom–up’ participatory methods, thus limiting their impact and reducing participation in planning by the community. Additionally, they underlined that when community leaders plan activities, they rarely involve as community members. Basically, only two to three persons are involved at the beginning of an activity [

58]. On the other hand, Cohen and Uphoff (1977) claimed that the evaluation process of community development projects is sometimes totally missing, and communities severely lack the tools of evaluation due to low literacy rates [

57]. Hence, this study managed to fill the gaps by showing that the planning and evaluation processes are not robust enough to empower UA communities. It also denotes that high planning and implementation is required among communities to ensure that the repercussion of UA is adequate to encourage empowerment among urban societies.

In this research, we also discovered that participation in program implementation influences social empowerment. Local governments (town planners) of urban areas need to consider several locations as potential spaces for urban dwellers, whether for housing areas that have already been developed or will be developed in the future. This deliberation is intended for the community to have areas to establish, improve, or expand UA activities. Substantially, coordination and cooperation between agencies and the establishment of a platform to promote all parties’ involvement in the implementation stage are required. These acts can foster awareness and interest in the importance of agriculture as a direct contributor to the well-being of urban communities [

27,

34,

60]. To ascertain the sustainment of urban community’s participation, the private sector and hypermarkets can also develop initiatives that promote the purchase of planting tools, seeds, and fertilizers at affordable prices, hence increasing demand for agriculture crops. On the other hand, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can use media platforms to provide simple technological manuals or organize weekend mini-courses on agriculture to provide hands-on activities that can generate interest amongst communities.

Furthermore, UA should be prioritized as a way to contain urban dwellers’ rising poverty rate through the lowering of family expenditures. It was unnoticed that the Malaysian government has provided a hefty budget for UA communities in certain areas to develop and operate UA programs/activities. Nonetheless, apart from start-up funds, technical support should also be offered for the cultivation of crops in low-cost residential flats with limited space in order to ensure a supply of fresh produce for residents. Although UA practices are not new in Malaysia, their implementation is still scarce; hence, thorough assistance and prolonged cooperation either from government bodies, private agencies, or NGOs are much coveted. This is associated with this study’s findings, which signified the importance of linking social capital to the implementation process. The significant advantage of such efforts is that they have the ability to reshape urban populations when undertaken collectively [

60].

Through planning, implementation, and assessment, UA has the ability to achieve the social empowerment goals of managing sustainable slums and managing urbanization as part of urban settlement planning. Although there is no clear link between urban agriculture and urban poverty, social empowerment through UA can help alleviate poverty and meet urban food demands, as urban agriculture can inspire small businesses to sell vegetables and compost [

61]. As a result of the technology used, such as horticulture, hydropower, rooftop, and aquaponics, UA does not require a significant area of land, and it can be replicated without a large area of land. As a result, it may serve as the household’s primary source of food, and it plays an important role in reducing the food insecurity. Urban agriculture improves the economic situations as well as the health of poor and vulnerable families, particularly women and children, despite the fact that it is still widely regarded as a transient or peripheral activity that does not lead to long-term urban development. Furthermore, UA integrates agricultural and urban development challenges. It has a direct and indirect impact on the citizens’ quality of life in numerous ways. Agriculture in urban areas is generally regarded as a resource that contributes to food security for families and communities as well as the improvement of living conditions in poor neighbourhoods in both developing and developed countries, so it would be a good program to increase the social empowerment of the people in Klang Valley, Malaysia.

Further, UA has the ability to contribute to the development of substantial capacities for planning, project implementation, and collective action at the neighborhood level. To do local development work, the UA program relies on solid community organizations with strong planning and implementation capacities. With effective and stable support from stakeholders, implementation of the program could educate the community on UA initiatives and how they can be improved. When government actions are integrated with community needs, strong social cohesion among the community could evolve, therefore creating an agriculture knowledgeable society. Eventually, dependency on third parties is no longer required as people can manage the crops on their own. In other words, the initiatives that were first pioneered by stakeholders are promptly handled by the participants themselves. Hence, through this process, the community will become self-reliant and more empowered.

5. Conclusions

The research has indicated the important role of participation in the planning, implementation, and evaluation stages in order to ensure the success of UA programs. Although there is less surface area of agricultural land available in the city, and it would be difficult to feed the entire population of a city such as the Klang Valley area, Malaysia with the available land, a multi-approach implementation of gardening in urban environments, such as land agriculture, container gardening on balconies and roofs, and a vertical integration of elements would certainly contribute to the social empowerment of disadvantaged neighborhoods. Moreover, the role of agencies, NGOs, and communities in building strong linkages is crucial to the enhancement of social empowerment among UA program participants in the study area. As a program at the community level, UA can be a platform for participation in many communities, especially those in low-income urban areas, as the effort also works as an alternative to managing household expenses in terms of fresh produce for daily needs. Therefore, the success of UA programs initiated by the Department of Agriculture requires not only the community’s effort but also the support of related agencies and other organizations linked through social capital in order to ensure the program’s sustainability.

Moreover, UA is a way to enhance food security and offer environmental health and social benefits. At the same time, the availability of fresh, home-grown food products, in particular fruits and vegetables through UA, advances the nutritional status of household members and thereby improves health. Direct access to food often allows particularly poor households to consume a more diverse diet than they would otherwise be able to afford. In his study, Maxwell (1998) connected the aspect of maternal care to UA, arguing that mothers engaged in UA, as opposed to other forms of non-farm employment away from home, have an increased ability to care for their children [

62]. This was in return believed to positively impact levels of child nutrition and their food security. Further, UA is assumed to create an “opportunity cost”—domestic producers can either save income, via the consumption of home-produced foodstuffs that are cheaper to produce than to buy from the market, and/or increase income by selling or trading their products. Hence, higher cash income at the household level is positively linked to food security as households are believed to have greater access to food products both in terms of quantity and quality.

The outcomes of this study are restricted to the Malaysian respondents who were the participants of UA community programs authorized by the Department of Agriculture in the Klang Valley area. Due to potential inequalities in people’s attitudes and behaviors, a sample covering diverse populations could produce different results, and further investigations should be undertaken with different contexts and nations in order to reduce location feedbacks. The sample size of this study was 180 respondents, and the large sample size would be ideal to increase the validity of the results. Furthermore, the authors cannot make any casual claims or evaluate the links between the investigated antecedents and social empowerment over time due to the cross-sectional nature of this study. Research designs that allow for causal inference are required to conduct a true causal examination of the impact of individual social empowerment over time with a longitudinal design. Moreover, future research should build on this work by developing and testing integrated comprehensive models with the goal of capturing a more holistic knowledge of the underlying causes of social empowerment.