Environmental Governance at an Asymmetric Border, the Case of the U.S.–Mexico Border Region

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How good is the current environmental cross-border governance at the U.S.–Mexico border region?

- What sort of measures should be taken to address complex and long-term environmental problems in U.S.–Mexico cross-border governance?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

- How good is the current environmental cross-border governance adopted at the U.S.–Mexico border region?

- What sort of measures should be taken to address the complex and long-term environmental problems in U.S.–Mexico cross-border governance?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Comisión Europea. La gobernanza Europea; Un libro Blanco; Comisión Europea: Bruselas, Bélgica, 2001; p. 428. [Google Scholar]

- Delreux, T. Regional Governance. In Essential Concepts of Global Environmental Governance; Morin, J.-F., Orsini, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; p. 252. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschke, S.; Borchardt, D.; Newig, J. Mapping Complexity in Environmental Governance: A comparative analysis of 37 priority issues in German water management. Environ. Policy Gov. 2017, 27, 534–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underdal, A. Complexity and challenges of long-term environmental governance. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.J.; Smith, C.; Bellamy, J. Understanding enabling capacities for managing the ‘wicked problem’ of nonpoint source water pollution in catchments: A conceptual framework. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 128, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, B.W. Evidence, Uncertainty, and Wicked Problems in Climate Change Decision Making in Australia. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2014, 32, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conca, K. The Rise of the Region in Global Environmental Politics. Glob. Environ. Politics 2012, 12, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingqvist, G.Ö.; Drakenberg, O.; Slunge, D.; Sjöstedt, M.; Ekbom, A. The Role of Governance for Improved Environmental Outcomes. Perspectives for Developing Countries and Countries in Transition; Naturvårdsverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012; p. 59.

- Badenoch, N. Transboundary Environmental Governance. Principles and Practice in Mainland Southeast. Asia; World Resources Institute United States: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Durth, R. European experience in the solution of cross-border environmental problems. Intereconomics 1996, 31, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Brien, M.; Penna, S. European Policy and the Politics of Environmental Governance. Policy Politics 1997, 25, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrory, R.; Turner, S. Cross-border Environmental Governance: The EC Law Dimensions. Reg. Fed. Stud. 2002, 12, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurzel, R.K.; Zito, A.R.; Jordan, A.J. Environmental Governance in Europe: A Comparative Analysis of the Use of New Environmental Policy Instruments; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Capello, R.; Caragliu, A.; Fratesi, U. Measuring border effects in European cross-border regions. Reg. Stud. 2018, 52, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiering, M.; Verwijmeren, J.; Lulofs, K.; Feld, C. Experiences in Regional Cross Border Co-operation in River Management. Comparing Three Cases at the Dutch–German Border. Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 24, 2647–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scherer, R.; Zumbusch, K. Limits for successful cross-border governance of environmental (and spatial) development: The Lake Constance Region. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 14, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munteanu, A.M.; Ehlinger, T.; Golumbeanu, M.; Tofan, L. Network environmental governance in the EU as a framework for trans-boundary sturgeon protection and cross-border sustainable management. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2013, 14, 685–692. [Google Scholar]

- Vulevic, A.; Castanho, R.A.; Gómez, J.M.N.; Lausada, S.; Loures, L.; Cabezas, J.; Fernández-Pozo, L. Cross-Border Cooperation and Adaptation to Climate Change in Western Balkans Danube Area. In Governing Territorial Development in the Western Balkans; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, T.R.; Benzie, M.; Campiglio, E.; Carlsen, H.; Fronzek, S.; Hildén, M.; Reyer, C.P.; West, C. A conceptual framework for cross-border impacts of climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 69, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamman, P. (Ed.) Cross-Border Renewable Energy Transitions: Lessons from Europe′s Upper Rhine Region; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Blatter, J. Emerging cross-border regions as a step towards sustainable development? Experiences and considerations from examples in Europe and North America. Int. J. Econ. Dev. 2000, 2, 402–440. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, S.E. Spatial concepts and cross-border governance strategies: Comparing North American and Northern Europe experiences. In Proceedings of the EURA Conference on Urban and Spatial European Policies, Turin, Italy, 18–20 April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Oddone, N.; Vázquez, H.R.; Oro, M.J. Local cross-border paradiplomacy as an environmental governance tool in Mercosur and the European Union: A comparative approach. Civitas-Rev. de Cienc. Sociais 2018, 18, 332–350. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, L. ASEAN and environmental governance: Rethinking networked regionalism in Southeast Asia. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 14, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, M.A.; Middleton, C.; Rigg, J.; Taylor, D. Hybrid Governance of Transboundary Commons: Insights from Southeast Asia. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2019, 110, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyaka, V. Politics of Civil Society Organizations on Environmental Governance in ASEAN. Creating ASEAN Futures 2015: Towards Connected Cross-Border Communities. In Proceedings of the International Indonesian Forum for Asian Studies, Andalas University, Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia, 28–29 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Tao, J. Cross-border environmental governance in the Greater Pearl River Delta (GPRD). Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2010, 67, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, X.; Wu, H.; Liu, L. Trade-off between economic development and environmental governance in China: An analysis based on the effect of river chief system. China Econ. Rev. 2019, 60, 101403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Sun, Y.; Han, Y. Regional environmental governance of the Yellow Sea and Bohai Sea from the perspective of land and sea coordination: Conference report. Mar. Policy 2021, 127, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yijing, C.; Jue, W. Study on the Cooperation Mechanism of Transboundary Water Pollution Control in China from the Perspective of Network Governance. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 136, 06009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S. Ecosystem Governance in a Cross-Border Area: Building a Tuman River Transboundary Biosphere Reserve. China Environ. Ser. 2005, 7, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Yok-shiu, F.L. Tackling cross-border environmental problems in Hong Kong: Initial responses and institutional constraints. China Q. 2002, 172, 986–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, G.R.; Connell, D.; Taylor, B.M. Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin: A Century of Polycentric Experiments in Cross-Border Integration of Water Resources Management. Int. J. Water Gov. 2013, 1, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimani, N. A Collaborative Approach to Environmental Governance in East Africa. J. Environ. Law 2009, 22, 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Catacutan, D.; Malesu, M. Multi-Stakeholder Platforms for Cross-Border Biodiversity Conservation and Land-Scape Governance in East Africa: Perspectives and Outlook; World Agroforesty (ICRAF): Nairobi, Kenia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Godsäter, A. Regional Environmental Governance in the Lake Victoria Region: The Role of Civil Society. Afr. Stud. 2013, 72, 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boillat, S.; Scarpa, F.M.; Robson, J.P.; Gasparri, N.I.; Aide, T.M.; Aguiar, A.P.D.; Anderson, L.O.; Batistella, M.; Fonseca, M.; Futemma, C.; et al. Land system science in Latin America: Challenges and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R. The politics of global environmental governance: The powers and limitations of transfrontier conservation areas in Central America. Rev. Int. Stud. 2005, 31, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, A.B. Transboundary Environmental Governance Across the World’s Longest Border. Glob. Environ. Politic 2019, 19, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, J. Border Paradox: Striking a Balance between Access and Control in Asymmetrical Border Settings. Eurasia Bor. Rev. 2012, 3, 51–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wong Villanueva, J.L.; Kidokoro, T.; Seta, F. Cross-Border Integration, Cooperation and Governance: A Systems Approach for Evaluating “Good” Governance in Cross-Border Regions. J. Borderl. Stud. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States International Trade Commission (USITC). The Impact of Increased United States—Mexico Trade on Southwest Border Development; United States International Trade Commission (USITC): Washington, DC, USA, 1986.

- Martinez, O. Borderlands Entering a New Stage. Mex. Policy News 1992, 8, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, F. Networking on the border. The Realities on Communication among Border entities. In Building a Strong Region Through Effective Communication. Seizing Opportunities in the California-Baja California Region; San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG): San Diego, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, S. Cross-border planning at the U.S.-Mexico border: An institutional approach. J. Borderl. Stud. 2007, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Alfie Cohen, M.; Flores Jauregui, O. Las agencias ambientales binacionales de México y Estados Unidos: Balance y perspectiva a dieciséis años de su creación. Norteamérica 2010, 5, 129–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hufbauer, G.; Jones, R. North American Convergence: An American Perspective; SICE, Foreign Trade Information System: Miami, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mumme, S.P.; Collins, K. The La Paz Agreement 30 Years On. J. Environ. Dev. 2014, 23, 303–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumme, S. Reflections on Public Participation in Environmental Protection Policy on the U.S.–Mexico Border. Retos Ambientales y Desarrollo Urbano en la Frontera Mexico-Estados Unidos; DeparTamento de Estudios Urbanos y Medio Ambiente, Eds.; Colegio de la Frontera Norte: Tijuana, Mexico, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nam Kwon, M.; Andrés-Rosales, R.; Quintana Romero, L. Crecimiento económico y la contaminación medioambiental en las ciudades mexicanas. J. Iber. Lat. Am. Res. 2016, 22, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zito, A.; Aspinwall, M. Green Regions? Comparing Civil Society Activism in NAFTA and the European Union. Perf. Latinoam. 2016, 24, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, K.P. El TLCAN y el Medio Ambiente: Lecciones de México y Más Allá. In El Futuro de la Política de Comercio en America del Norte: Lecciones del TLCAN; Pardee Center Task Force Report; Gallagher, K.P., Peters, E.D., Wise, T.A., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, Doctorado en Estudios de Desarrollo: Zacatecas, Mexico; Tufts University, Global Development and Environment Institute: Somerville, MA, USA; Boston University Frederick, S. Pardee Center: Boston, MA, USA; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Centro de Estudios China-México: Mexico City, Mexico; Miguel Ángel Porrúa: Mexico City, Mexico, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Rodriguez, R.A.; Mumme, S.P. Protecting the Environment? In Mexico and the United States: The Politics of Partnership, 1st ed.; Smith, P., Seeley, A., Eds.; Lynne-Reinner Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2013; pp. 139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Malkawi, B.H.; Kazmi, S. Dissecting and Unpacking the USMCA Environmental Provisions: Game-Changer for Green Governance? JURIST: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

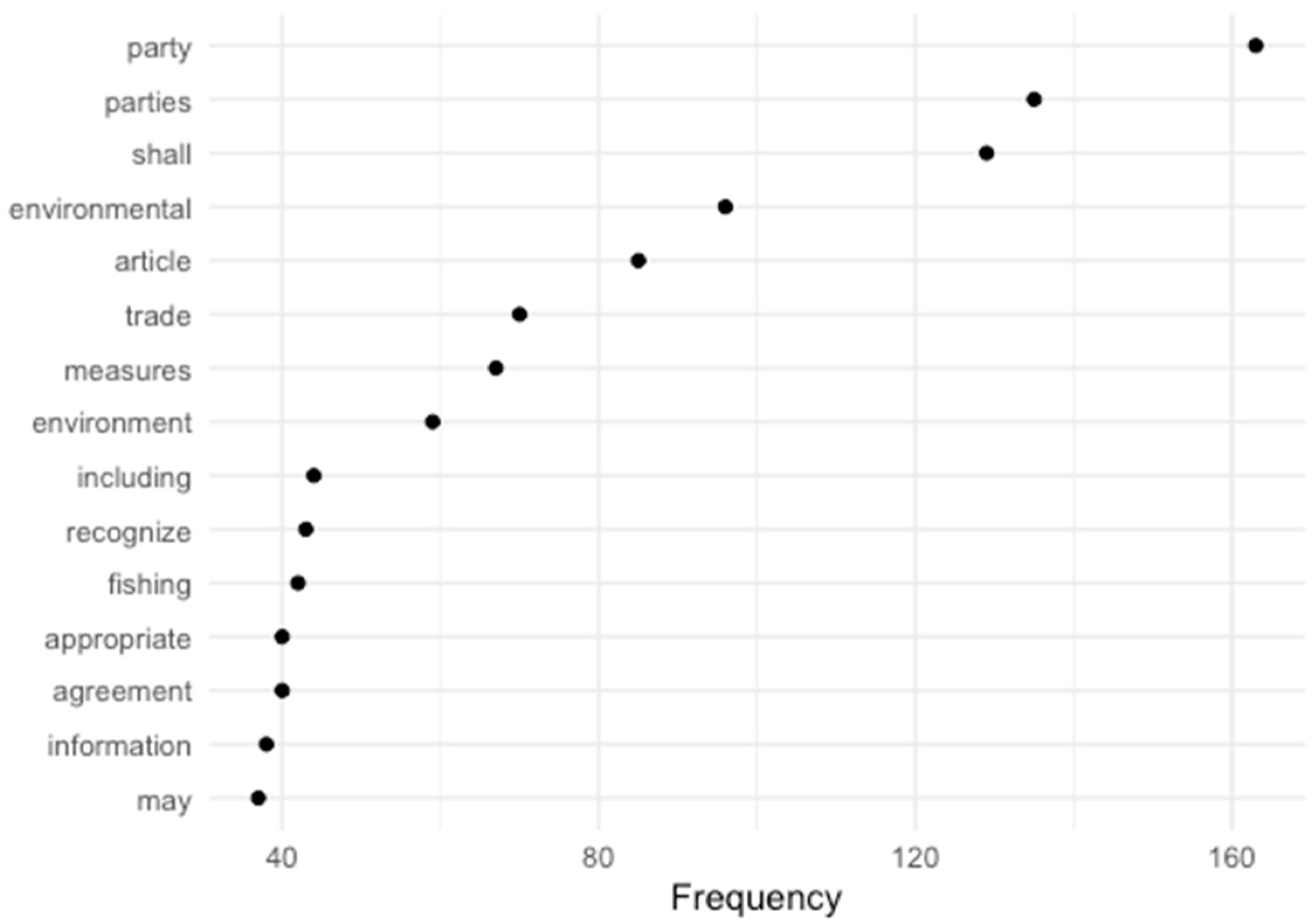

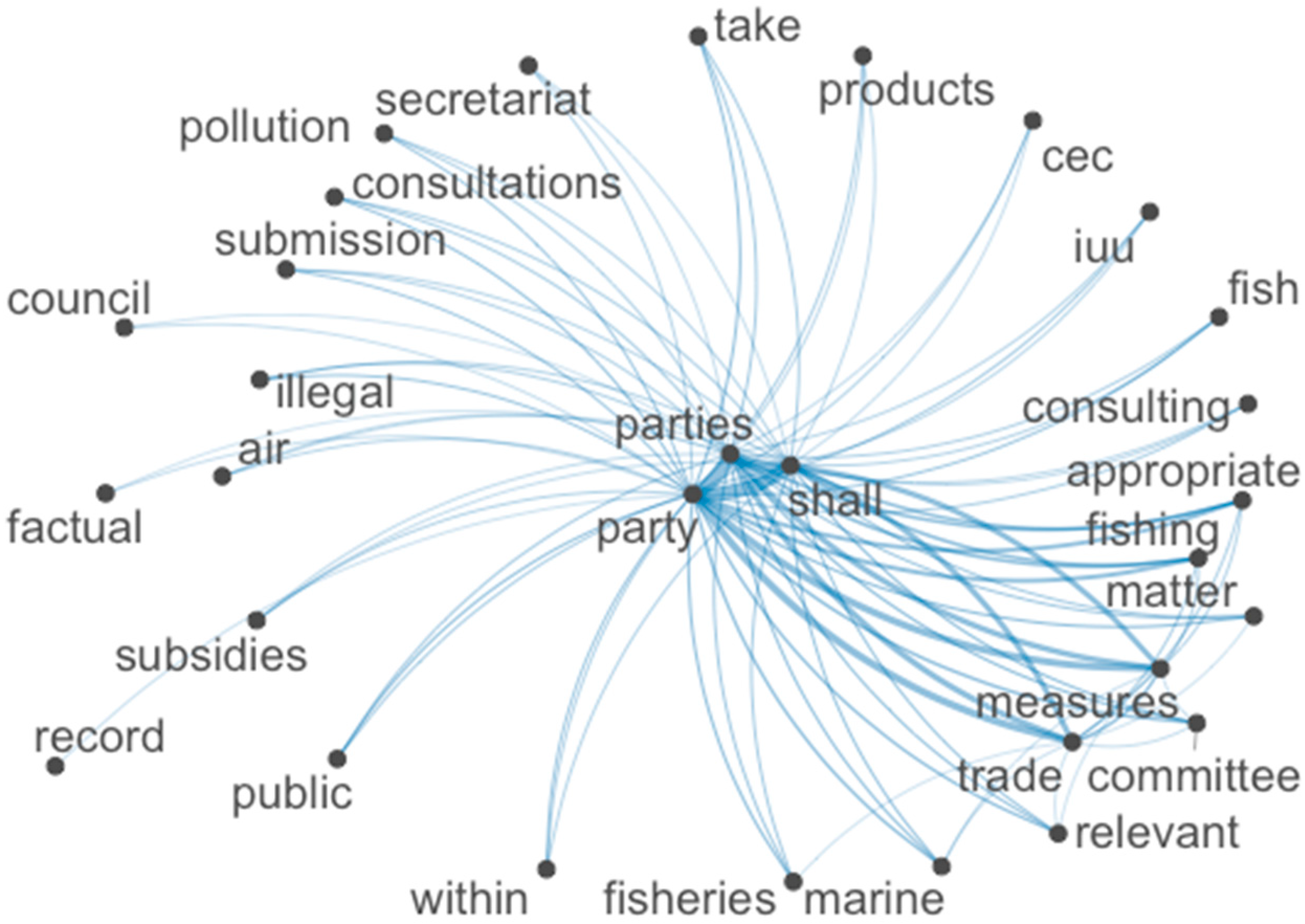

- Benoit, K.; Watanabe, K.; Wang, H.; Nulty, P.; Obeng, A.; Müller, S.; Matsuo, A. quanteda: An R package for the quantitative analysis of textual data. J. Open Source Softw. 2018, 3, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Criteria | Description | Representative Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| Common agenda and national sovereignty | A common cross-border integration agenda respecting the principle of national sovereignty | purpose, objectives, goals, priorities |

| Stable organizational structure | Institutional and legal framework in each country involving inter- and intra-sectorial structures and their evolution, ensuring functionality | local, regional, international, legal, institutional, structures, inter |

| Multi-level model | An agreed governance level and recognition of key actors with a clear relations framework | rules, procedures |

| Institutional mix and articulations | Enhancement of institutional variety Articulation of formal and informal stakeholders and mechanisms | stakeholders |

| Bonding links | Strengthening of network relations in formal ways and links | mutual, relations |

| Internal and externalcommunication | Effective channels for internal communication and external visualization | communication |

| Growth potentials | Identification of growth potentials (development levers) Understand the interaction of growth potential with territorial processes Sufficient resources and capacities for executing plans | potential, development, growth, process |

| Key actors, resources and goals | Identification of key actors in priority issues | factors, resources, sectors, issues |

| Goal setting and planning | Clear roadmap with long-term, medium-term and short-term planning | risk, management |

| Accountability | Ensure transparency, access to information and awareness vertically and horizontally | regulation, review, decision |

| CBG Criteria | Number of Times Criteria Is Addressed | Representative Keywords (Mentions) |

|---|---|---|

| Common agenda and nationalsovereignty | 22 | purpose (5), objectives (10), goals (2), priorities (5) |

| Stable organizational structure | 38 | local (2), regional (8), international (18), legal (6), institutional (3), structures (1), inter (1) |

| Multi-level model | 9 | rules (3), procedures (6) |

| Institutional mix and articulations | 1 | stakeholders |

| Bonding links | 9 | mutual (8), relations (1) |

| Internal and external communication | 2 | communication |

| Growth potentials | 25 | potential (3), development (19), growth (2), process (1) |

| Key actors, resources and goals | 26 | factors (1), resources (26), sectors (2), issues (7) |

| Goal setting and planning | 28 | risk (2), management (26) |

| Accountability | 16 | regulation (10), review (5), decision (1) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Munoz-Melendez, G.; Martinez-Pellegrini, S.E. Environmental Governance at an Asymmetric Border, the Case of the U.S.–Mexico Border Region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031712

Munoz-Melendez G, Martinez-Pellegrini SE. Environmental Governance at an Asymmetric Border, the Case of the U.S.–Mexico Border Region. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031712

Chicago/Turabian StyleMunoz-Melendez, Gabriela, and Sarah E. Martinez-Pellegrini. 2022. "Environmental Governance at an Asymmetric Border, the Case of the U.S.–Mexico Border Region" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031712