Enabling School Bureaucracy, Psychological Empowerment, and Teacher Burnout: A Mediation Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Empowerment Theory

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Enabling Bureaucracy and Teacher Burnout

3.2. Psychological Empowerment and Teacher Burnout

3.3. Mediation Effect of Psychological Empowerment

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

4.2. Measurement

4.2.1. Enabling School Bureaucracy

4.2.2. Psychological Empowerment

4.2.3. Teacher Burnout

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Correlation Analysis

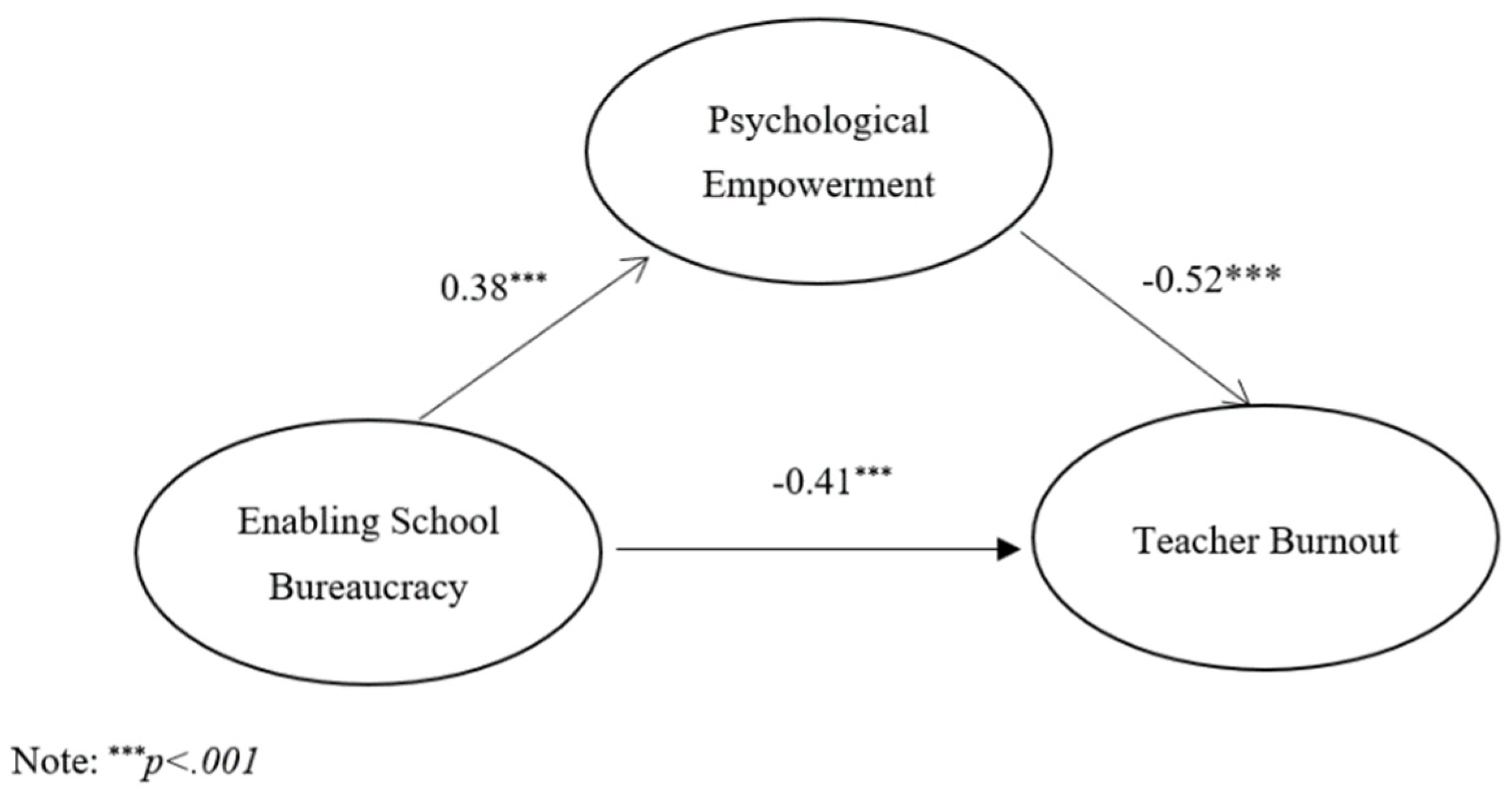

5.2. Mediation Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saloviita, T.; Pakarinen, E. Teacher burnout explained: Teacher-, student-, and organisation-level variables. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 97, 103221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.L. Toward a theoretical model to understand teacher emotions and teacher burnout in the context of student misbehavior: Appraisal, regulation and coping. Motiv. Emot. 2013, 37, 799–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakke, B.; van Peet, A.; van der Wolf, K. Challenging parents, teacher occupational stress and health in Dutch primary schools. Int. J. About Parents Educ. 2007, 1, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan, B. Comparing teachers’ work with work in other occupations: Notes on the professional status of teaching. Educ. Res. 1994, 23, 4–17+21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brante, C. Multitasking and synchronous work: Complexities in teacher work. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2009, 25, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Tsang, A.; Kwok, K. Stress and mental disorders in a representative sample of teachers during education reform in Hong Kong. J. Psychol. Chin. Soc. 2007, 8, 159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Squillaci, M. Are teachers more affected by burnout than physicians, nurses and other professionals? A systematic review of the literature. In Advances in Human Factors and Ergonomics in Healthcare and Medical Devices; Lightner, N., Kalra, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. The Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 4th ed.; CPP, Inc.: Sunnyvale, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, R.; Schonfeld, I.S.; Mayor, E.; Laurent, E. Burnout-depression overlap: A study of New Zealand schoolteachers. N. Z. J. Psychol. 2016, 45, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- García-Carmona, M.; Marín, M.D.; Aguayo, R. Burnout syndrome in secondary school teachers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 22, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsimani, P.; Montgomery, A.; Georganta, K. The Relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akdemir, Ö.A. The effect of teacher burnout on organizational commitment in Turkish context. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2019, 7, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iancu, A.E.; Rusu, A.; Măroiu, C.; Păcurar, R.; Maricuțoiu, L.P. The effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing teacher burnout: A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 30, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C.M. Job stressors, personality and burnout in primary school teachers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 77, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.W.; Hui, E.K.P. Burnout and coping among Chinese secondary school teachers in Hong Kong. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1995, 65, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.W. Emotional intelligence and components of burnout among Chinese secondary school teachers in Hong Kong. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2006, 22, 1042–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietarinen, J.; Pyhältö, K.; Soini, T.; Salmela-Aro, K. Reducing teacher burnout: A socio-contextual approach. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 35, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Preventing Burnout and Building Engagement. A Complete Program for Organizational Renewal; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Betoret, F.D. Self-efficacy, school resources, job stressors and burnout among Spanish primary and secondary school teachers: A structural equation approach. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friedman, I.A. High- and low-burnout schools: School culture aspects of teacher burnout. J. Educ. Res. 1991, 84, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner, C.; Martinez-Tur, V.; Peiro, J.M.; Ramos, J.; Cropanzano, R. Relationships between organizational justice and burnout at the work-unit level. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Dimensions of teacher burnout: Relations with potential stressors at school. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2017, 20, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and thehir relationship with burnout and engagment: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwab, R.L. Teacher burnout: Moving beyond “psychobabble”. Theory Pract. 1983, 22, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.S.; Borys, B. Two types of bureaucracy: Enabling and coerecive. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoy, W.K.; Sweetland, S.R. Besigning better schools: The meaning and measure of enabling school structures. Educ. Adm. Q. 2001, 37, 296–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadan, E. Empowerment and Community Planning: Theory and Practice of People-Focused Social Solutions; Hakibbutz Hameuchad: Tel Aviv, Israel, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.; Checkoway, B. Futher explorations in empowerment theory: An empirical analysis of psychological empowerment. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1992, 20, 707–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, J. Studies in empowerment: Introduction to the issue. Prev. Hum. Serv. 1984, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R. The theory of empowerment: A critical analysis with the theory evaluation scale. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2020, 30, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eljaaidi, N. Structural and psychological empowerment: A literature review, theory clarifications and strategy building. J. Econ. Political Sci. 2016, 7, 446–479. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, R.M. Men and Women of the Corporation, 2nd ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, P.K.; Ungson, C.R. Reassessing the limits of structural empowerment: Organizational constitution and trust as controls. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, J.A.; Kanungo, R.N. The empowerment process: Integrating theory and practice. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Taebi, M.; Simbar, M.; Abdolahian, S. Psychological empowerment strategies in infertile women: A systemic review. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, S.H.K.; Finegan, J.; Shamian, J.; Wilk, P. Impact of strutural and psychological empowerment on job strain in nursing work settings. J. Nurs. Adm. 2001, 31, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paryadharshany, A.J.; Sujatha, S. Does structural empowerment impact on job satisfaction via psychological empowerment? A mediation analysis. Glob. Manag. Rev. 2015, 10, 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Ye, H.; Li, Y. Correlates of structural empowerment, psychological empowerment and emotional exhaustion among registered nurses: A meta-analysis. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 42, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidenstedt, L. A Sociology of Empowerment: The Relevance of Communicative Contexts for Workplace Change; Stockholm University: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, R.M. The anomaly of educational organizations and the study of organizational control. In The Social Organization of Schooling; Hedges, L.V., Schneider, B., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.T.-L.; Kwan, P.; Li, B.Y.M. Neoliberal challenges in context: A case of Hong Kong. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2020, 34, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K. Social Theory and Social Structure; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B.D. School bureaucratization and alienation from high school. Sociol. Educ. 1973, 46, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, A.G. Teacher burnout and teacher resilience: Assessing the impact of the school accountability movement. In International Handbook of Research on Teachers and Teaching; Saha, L.J., Dworkin, A.G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 491–509. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, K.S.; Hoy, W.K.; Hoy, A.W. Academic optimism of individual teachers: Confirming a new construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, K.K.; Liu, D. Teacher demoralization, disempowerment and school administration. Qual. Res. Educ. 2016, 5, 200–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, T.O.; Yeung, A.S. Hong Kong teachers’ sources of stress, burnout, and job satisfaction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Teacher Education, Hong Kong, China, 22–24 February 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, D.A. Teacher Demoralization and Teacher Burnout: Why the Distinction Matters. Available online: http://www.ajeforum.com/teacher-demoralization-and-teacher-burnout-why-the-distinction-matters/ (accessed on 9 May 2015).

- Powell, W.E. The Relationship between Feelings of Alienation and Burnout in Social Work. Fam. Soc.: J. Contemp. Soc. Serv. 1994, 75, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, F.; Ren, S.; Di, Y. Locus of control, psychological empowerment and intrinsic motivation relation to performance. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudrias, J.-S.; Morin, A.J.S.; Brodeur, M.-M. Role of psychological empowerment in the reduction of burnout in Canadian healthcare workers. Nurses Health Sci. 2012, 14, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaniyoun, A.; Shakeri, K.; Heidari, M. The association of psychological empowerment and job burnout in operational staff of Tehran emergency center. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 21, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.L. An inquiry into the relatsionhip between primary school teacher burnout and psychological empowerment. Contemp. Educ. Sci. 2013, 24, 30–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, K.K.; Du, Y.; Teng, Y. Transformational leadership, teacher burnout, and psychological empowerment: A mediation analysis. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2022, 50, e11041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, M.T.; Gilson, L.L.; Mathieu, J.E. Empowerment—Fad or Fab? A multilevel review of the past two decades of research. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1231–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knol, J.; Linge, R.V. Innovative behaviour: The effect of strutural and psychological empowerment on nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Jin, Y.; Guo, J. Mediating and/or moderating roles of psychological empowerment. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2016, 30, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tian, B.; Shi, K. Transformational leadership and employee work attitudes: The mediating effects of multidimensional psychological empowerment. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2006, 38, 297–307. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Wang, H. Relationship between time management and job burnout of teachers. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 17, 107–109. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, K.K. The structural causes of teacher burnout in Hong Kong. Chin. Educ. Soc. 2018, 51, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, L.C.; Moomaw, W. The relationship between teacher autonomy and stress, work satisfaction, empowerment, and professionalism. Educ. Res. Q. 2005, 29, 38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Luster, T.; McAdoo, H. Family and child influences on educational attainment: A secondary analysis of the high/scope Perry Preschool data. Dev. Psychol. 1996, 32, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, K.K. Teachers’ Work and Emotions: A Sociological Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| S | MD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Enabling structure | 3.30 | 0.82 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. Teacher burnout | 3.48 | 1.12 | −0.48 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 3.Emotional exhaustion | 4.30 | 1.63 | −0.39 ** | 0.85 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 4. Depersonalization | 3.81 | 1.69 | −0.44 ** | 0.88 ** | 0.80 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 5.Lack of accomplishment | 2.58 | 1.16 | −0.28 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.11 | 0.22 ** | 1 | |||||

| 6.Psychological empowerment | 3.89 | 0.84 | 0.39 ** | −0.53 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.34 ** | −0.63 ** | 1 | ||||

| 7. Meaning | 4.04 | 0.89 | 0.38 ** | −0.54 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.38 ** | −0.60 ** | 0.88 ** | 1 | |||

| 8. Competence | 4.11 | 0.89 | 0.24 ** | −0.49 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.30 ** | −0.65 ** | 0.85 ** | 0.78 ** | 1 | ||

| 9.Self-determination | 3.77 | 1.02 | 0.38 ** | −0.46 ** | −0.26 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.53 ** | 0.91 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.65 ** | 1 | |

| 10. Impact | 3.64 | 1.03 | 0.38 ** | −0.42 ** | −0.23 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.49 ** | 0.89 ** | 0.66 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.83 ** | 1 |

| Outcome Variables | Independent Variables | Coef. | SE | T | 95%CI | R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher Burnout | |||||||

| Constant | 5.37 *** | 0.69 | 7.74 | [4.00,6.37] | 0.25 | 25.41 *** | |

| Sex | −0.08 | 0.13 | −0.64 | [−0.34,0.17] | |||

| Age | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.68 | [−0.03,0.06] | |||

| Teaching age | −0.03 | 0.02 | −1.38 | [−0.07,0.01] | |||

| Enabling school bureaucracy | −0.60 *** | 0.07 | −8.68 | [−0.74,−0.47] | |||

| Psychological Empowerment | |||||||

| Constant | 2.76 *** | 0.55 | 5.03 | [1.68,3.84] | 0.17 | 15.53 *** | |

| Sex | −0.12 | 0.10 | −1.18 | [−0.32,0.08] | |||

| Age | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.03,0.03] | |||

| Teaching age | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.54 | [−0.02,0.04] | |||

| Enabling school bureaucracy | 0.38 *** | 0.06 | 6.96 | [0.28,0.49] | |||

| Teacher Burnout | |||||||

| Constant | 6.79 *** | 0.66 | 10.31 | [5.50,8.09] | 0.37 | 36.82 *** | |

| Sex | −0.15 | 0.12 | −1.23 | [−0.38,0.09] | |||

| Age | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.75 | [−0.02,0.06] | |||

| Teaching age | −0.02 | 0.02 | −1.26 | [−0.06,0.01] | |||

| Enabling school bureaucracy | −0.41 *** | 0.07 | −5.94 | [−0.54,−0.27] | |||

| Psychological Empowerment | −0.52 *** | 0.07 | −7.90 | [−0.65, 0.39] |

| Effect | Bootstrap Standard Error | Bootstrap LLCI | Bootstrap ULCI | Relative Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effects | −0.60 | 0.09 | −0.78 | −0.44 | |

| Direct Effects | −0.41 | 0.09 | −0.58 | −0.23 | 67.22% |

| Mediation Effects of Psychological Empowerment | −0.20 | 0.04 | −0.29 | −0.12 | 32.77% |

| Effect | Standard Error | Bootstrap LLCI | Bootstrap ULCI | Effect Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Mediation Effect | −0.18 | 0.05 | −0.28 | −0.08 | 29.24% |

| Meaning | −0.11 | 0.04 | −0.19 | −0.03 | 18.04% |

| Competence | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.09 | −0.01 | 7.34% |

| Self-determination | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.18 | 0.02 | 11.64% |

| Impact | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.15 | 7.77% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsang, K.K.; Wang, G.; Bai, H. Enabling School Bureaucracy, Psychological Empowerment, and Teacher Burnout: A Mediation Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042047

Tsang KK, Wang G, Bai H. Enabling School Bureaucracy, Psychological Empowerment, and Teacher Burnout: A Mediation Analysis. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042047

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsang, Kwok Kuen, Guangqiang Wang, and Hui Bai. 2022. "Enabling School Bureaucracy, Psychological Empowerment, and Teacher Burnout: A Mediation Analysis" Sustainability 14, no. 4: 2047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042047

APA StyleTsang, K. K., Wang, G., & Bai, H. (2022). Enabling School Bureaucracy, Psychological Empowerment, and Teacher Burnout: A Mediation Analysis. Sustainability, 14(4), 2047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042047