1. Introduction

This paper focuses on vegan food (i.e., food containing no ingredient sourced from animals) and the motivations for individuals to select vegan food options for consumption. This is a very important topic in the context of the environmental problems facing our planet, such as global warming and climate change at large. Reported as a more sustainable alternative to the consumption of food produced by contemporary agriculture (i.e., based on meat and dairy products), increasing the consumption of vegan food can help mitigate these major concerns.

Veganism is experiencing a considerable surge in popularity among the general population [

1,

2,

3,

4], having become more mainstream in the past 15 years, with a larger proportion of the American population, for instance, adhering to the diet than ever before [

5,

6]. In light of environmental considerations, the vegan diet represents a clear advantage compared to an omnivorous diet, which has, on average, a much greater carbon, water, and ecological footprint. In fact, animal agriculture is responsible for approximately 18% of global greenhouse gas emissions, an amount greater than the entire transport sector [

7]. Meanwhile, an estimated 70% of the world’s agricultural land is now dedicated to livestock production, which has contributed to biodiversity loss, soil degradation, and air and water pollution. Therefore, to improve environmental sustainability, animal-based food should be replaced with a plant-based (i.e., vegan) diet that emphasises fruits, vegetables, legumes, and cereals, according to worldwide recommendations and nutritional guidelines [

8].

The literature suggests several reasons why individuals switch to vegan food, including ethical motivations, environmental concerns, religious beliefs, cultural issues, health-related aspects, and even disgust towards meat [

3,

4,

9]. While most scholars agree that, rather than a single motivation acting in isolation, there is a complex interplay of motivational factors driving vegan food selection [

10,

11], recent research [

12] shows that the three most important drivers are animal-related motives (89.7%), personal well-being and/or health motives (69.3%), and environment-related motives (46.8%).

Animal-related motives are not highly surprising given that veganism advocates ethical eating, striving to alleviate the suffering of animals by abstaining from the consumption of goods that have used animals at any stage of their production [

13]. Many also choose to become vegan for perceived health benefits [

14]. Indeed, several studies, including clinical research, have provided evidence of the nutritional benefits of a plant-based diet [

6,

15,

16]. For instance, the study reported in [

1] found that, among various dietary schemes, the vegan diet has the highest nutritional quality (while the omnivorous has the lowest), based on the HEI-2010 (Healthy Eating Index) and MDS (Mediterranean Diet Score). In a similar vein, reference [

2] compares vegan diets to a Mediterranean diet, finding support for the environmental and health impacts of the former. Vegan diets have additionally gained acceptance as a dietary strategy for maintaining good health by significantly lowering cholesterol and blood pressure and reducing the rates of chronic disease (including coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and cancer), as well as mortality [

3,

6,

9,

15,

16]. Appropriately planned vegan diets can be healthful, nutritionally adequate, and provide health benefits in terms of the prevention and treatment of certain diseases [

3,

9,

17].

The burgeoning interest in veganism has concurrently provided businesses with a unique opportunity to adapt to changing consumer demands and increase vegan food offerings [

7]. These businesses are represented by new, entrepreneurial ventures or existing companies that have expanded their product portfolios to reach the segments demanding vegan products [

18]. This is most famously illustrated by the meteoric rise of two Silicon Valley start-ups, Beyond Meat, Inc. (Los Angeles, CA, USA) and Impossible Foods, Inc. (Redwood, CA, USA), which have deployed sophisticated technological innovations to produce meat alternatives aimed at vegan as well as non-vegan consumers (so-called ‘flexitarians’), as well as the strategic shifts of the meat producers Tyson Foods, Inc. (Springdale, AK, USA) and JBS S.A. (Sao Paolo, Brazil)—the largest meat producers in the United States and in the world, respectively—towards plant-based options.

From a business point of view, it is important to understand what consumers appreciate in vegan food, in other words, the consumer’s ‘value proposition’, so that offerings can be designed and delivered in alignment. The value proposition outlines how a company plans to provide value to its consumers [

19] and is therefore considered to be one of the most important aspects of the company’s business model and entrepreneurial identity [

20]. Conceptualizations of value propositions have evolved significantly over time, progressing from a one-sided view of supplier-crafted value propositions that were simply intended to be ‘accepted’ by the consumer, to a contemporary view in which they are co-created by the supplier and the consumer [

21,

22,

23]. In this contemporary understanding, perceived value is the consumers’ overall assessment of the utility of a product based on their perception of what is received and what is given [

24]. Not surprisingly, it is highly individual and situational, meaning consumers weigh the components of perceived benefits and costs differently. For instance, some consumers may seek volume, whereas others desire high quality or convenience.

In order to be successful, therefore, businesses need to understand the value propositions that will be appreciated by their consumers and then provide what their consumers perceive as important [

25,

26]. A well-designed marketing strategy can significantly improve the communication of the value proposition to consumers, thus enhancing the consumer-perceived value. As a result, positive attitudinal and behavioural outcomes will follow, ultimately leading to the business’s financial success [

27]. Despite the growing evidence for the benefits of a well-designed and communicated value proposition, however, there is often a marked discrepancy between the value propositions of customers and sellers. This may be due to companies rarely adopting a systematic approach to value proposition development [

28].

While a noteworthy amount of research has been undertaken to understand why individuals transition to a vegan or vegetarian diet, the findings from these studies do not necessarily provide accurate insight for companies to model their businesses on [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Our knowledge of the value proposition for vegan food thus remains uncertain. In this paper, our ambition is to target this knowledge gap and to inform businesses that strive to develop attractive product and service offerings. Our purpose, more specifically, is to study the value proposition of vegan food as perceived by consumers. The research question we aim to answer is: What factors motivate consumers to increase their consumption of vegan food? By answering this question, we will determine the components of a consumer-perceived value proposition that food suppliers can strive to deliver.

Rather than following traditional approaches, such as conducting interviews or surveys of customer groups, we adopt a recently developed method to collect and analyse data pertaining to consumer-perceived value by monitoring the social media platform Twitter. Twitter is a micro-blogging service that consumers can use to communicate with each other using text messages of up to 280 characters together with images and other content. The platform has attracted the attention of researchers in recent years due to the real-time, large-scale and quickly propagating nature of the data it documents [

33]. At the same time, Twitter users freely express their thoughts and emotions to others such that accessing their messages provides a source of unsolicited opinion on specific topics [

34]. For this study, we collected tweets from Twitter’s streaming application programming interface (API) from 1 June 2018 to 30 May 2019 across Australia, searching for the keywords ‘vegan*’, ‘veganism’, and ‘plant based’. We then analysed these tweets (over 120,000 of them) using the textual data analytics software Leximancer which uses topic-modelling techniques and implicit coding to code text into concepts and overarching themes.

The structure of our paper is as follows. We begin with a review of the value propositions literature and then describe the methods employed to collect and analyse the Twitter data. In the following section we discuss the results of our investigation and end our paper with reflections on the study findings for businesses and on future extensions of our work.

2. Theoretical Discussion

The contributions of S-D (service-dominant) logic have played a huge role in the development of value proposition research. In comparison to G-D (goods-dominant) logic, which purely focuses on making and selling a product, S-D logic considers the total customer experience. This is now known to improve the success of a business, as application of S-D logic in creating and communicating a value proposition will enhance competitive advantage [

35].

S-D logic states that a company can only make value proposition offerings and that it is the customer who will determine the value proposition and co-produce it. The conventional meaning of value propositions is focused on supplier-created value, with no reciprocal communication between customers and suppliers. However, the more contemporary understanding of value propositions is that they are reciprocal promises of value exchanged between customers and suppliers, which means that the concept of value proposition is supported by S-D logic [

21]. In the exchange, the value perspectives of each party combine and form a reciprocal value proposition [

36]. As described by [

22], reciprocal engagement with relevant stakeholders is a key step in communicating the value proposition. In addition, reciprocal value propositions encourage trusting relationships which, in turn, maximise the potential for value-creating (or co-creating) activities [

21]. The concept of ‘value’ incorporates two complementary perspectives on customer value: value-in-exchange and value-in-use. Value-in-exchange places emphasis on the quality and price of products and services, whereas value-in-use reflects the value propositions which are expressed by either the seller or consumer. Essentially, a customer’s value-in-use is initiated by the value proposition [

36]. According to [

35], value-in-use is one of the most important concepts for a business. Thus, a customer would rather collaborate with a provider who offers more value-in-use compared to a provider who mainly focuses on value-in-exchange. Interestingly, this may reflect the length of the customer–supplier relationship. For example, longer-term customers may be more responsive to value-in-use and more likely to engage in co-creation activities, whereas short-term customers may benefit from value-in-exchange (as they may be reluctant to enter into close relationships with the supplier). Therefore, value is considered to be context-specific.

Meanwhile, customer-perceived value refers to the customer’s perception of the supplier and their offerings. Although customer-perceived value cannot be directly controlled by a company, it can be influenced by marketing strategies. This is because a well-designed marketing strategy can improve the communication of value propositions to customers. When the communication of a value proposition is enhanced, it will lead to an improved customer-perceived value. As a result, positive attitudinal and behavioural outcomes will follow and the firm will benefit financially [

27].

It is widely accepted that the value proposition is one of the most important aspects of a firm’s business model and entrepreneurial identity [

20]. A company can use a value proposition to communicate how it plans to provide value to its customers [

19]. An important step in the process of designing appropriate value propositions is targeting the right customers. In order to do this, companies must first identify target segments of the market and then create propositions specifically tailored to them. Unfortunately, the downside to identifying the right customers and understanding what motivates them requires painstaking research. However, when carried out correctly, companies can expect to reap benefits through financial gains [

26].

Our understanding of value propositions has evolved significantly since it was first discussed in the literature [

21,

22,

23]. It has progressed from the one-sided view of supplier-crafted value propositions that were simply intended to be ‘accepted’ by the customer, to a contemporary view in which both the supplier and customer co-create the value proposition. The authors of [

37] suggest that value cannot be created independently and that opportunities within the entrepreneurial marketing domain are constantly co-created. They describe a scenario in which a company can only propose a value possibility through communication of value propositions. The customer then needs to share their own value proposition. If they agree to each other’s value proposition, a service exchange can occur, and each party can co-create value. According to the authors, there is a four-phase co-creation process, which consists of: (i) developing the value proposition; (ii) communicating the value proposition; (iii) deriving and determining value; and (iv) (re)forming the market.

Although it has been demonstrated that co-created value propositions are an effective marketing strategy, a study conducted by the authors of [

38] found that there was a marked discrepancy between the value propositions of customers and sellers. This study suggests that, overall, customers have a much better understanding of what they can contribute to the co-creation process. As discussed in [

28], a potential reason for conflicting value propositions between buyers and sellers may be that companies rarely adopt a systematic approach to value proposition development. In order to maximise value creation, it is recommended that value propositions address relevant business goals of the stakeholders as well as leverage the supplier’s competitive advantage [

28,

39].

Scholars, e.g., the authors of [

40], have extended this view somewhat by proposing that a customer has two fundamental questions that need to be answered by the supplier. In essence, customers need to know why the offering is special and they also need to know why it will be worthwhile to support the company. In order to answer these questions, the authors recommend that the supplier create two different types of value proposition. The first is an innovative-offering value proposition, which communicates key points of difference and clearly outlines how customers can benefit from the offering. The second is a leveraging-assistance value proposition, which communicates the support and/or resources the company requires from the customer and what they will provide to the customer in return for this support/resources. Creating two separate value propositions allows the customer to make each assessment separately (i.e., they can first determine whether the innovative offering is valuable and then decide if providing the leveraged assistance will be worthwhile).

There are various ways in which consumers’ perceptions of value can be acquired by businesses. These include the use of traditional techniques, such as undertaking market surveys, focus groups, and interviews. However, the rise of social media platforms has offered an additional pathway for businesses to inquire about market attitudes. As illustrated by recent scientific work, e.g., [

41,

42,

43], it is possible to ‘listen’ to social media, where individuals express their views and perceptions regarding various topics, including products and services. In turn, the application of software to analyse social media data (i.e., textual data) can deliver insights on consumer opinions that can inform value proposition strategies.

4. Results

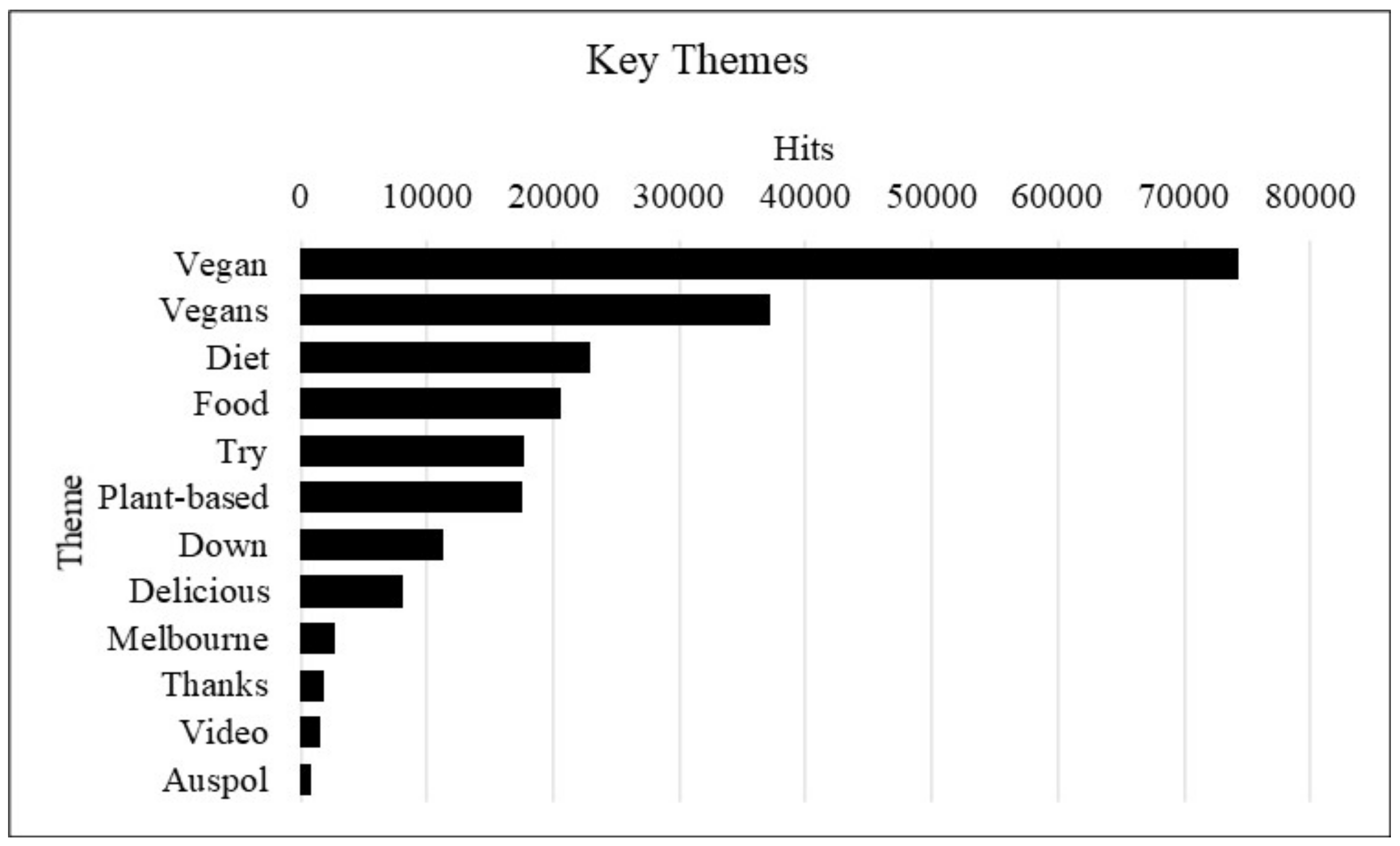

Our analysis produced 12 most prominent themes, which we present in

Figure 1 with respect to the number of hits associated with each in the dataset.

As the above graphic shows, the themes, ‘vegan’ and ‘vegans’ have, hardly surprisingly, distinctly the highest numbers of occurrences. The following two themes, ‘diet’ and ‘food’, were also anticipated to have gathered a high number of hits, together with ‘plant-based’. We additionally observe related descriptive themes in ‘try’ and ‘delicious’, together with somewhat distal themes, such as ‘down’ and ‘Melbourne’, which were captured in the data collection due to an event that took place in the city of Melbourne during the tweeting period.

In

Figure 2, below, we present the heat-map of these prominent themes produced by Leximancer (i.e., a standard view from the software) and the connections between these themes.

In the heat-map we once again confirm the dominance of the ‘vegan’ and ‘vegans’ themes, represented in the hottest colours as well as by the size of the circles. For each theme, we are also able to see sub-themes or concepts in Twitter conversation. For instance, tweets citing ‘vegan’ also mention ‘burger’, ‘sausage’, and even ‘nailpolish’. Despite the visibility of non-food related concepts in the heat-map, it is clear to see that food-related concepts are most dominant. In

Table 1, we summarise these themes together with the constellation of concepts within each.

We elaborate on each theme and related concepts below. We also underscore that, while it is not surprising that ‘vegan’ and ‘vegans’ are key themes (as they were keywords/hashtags used for data collection), it is important to note how these themes relate to others within the dataset.

Vegan: This theme was represented by an overwhelmingly high number of tweets associated with vegan food products and meals. The most frequently mentioned food categories/products were meat alternatives, including the ‘beyond meat’ burger and vegan sausage rolls, cheese, and cheesecake.

“Finally tried a ‘beyond meat’ burger. It was legit amazing.”

The term ‘delicious’ was often associated with mentions of vegan food alternatives. Several tweets were related to queries for vegan options at restaurants/cafes or pleas to companies to provide vegan options. It is also clear that vegan Twitter users use Twitter as a platform to encourage others to go vegan.

Vegans: Within this theme, tweeters used the ‘vegans’ concept as representing a collective (or individuals following a vegan lifestyle), about which they commented and conversed. Tweets were primarily based on negative views of vegans, including complaints of vegan protests causing disruption during the time of data collection.

“I think if Vegans are so damn into being vegan they need to stop lying about the names of their food. Soy sausage, vegan cheese, vegetable steak; you live in a world of lies and protein supplements.”

Diet: The cluster of tweets belonging to this theme included those highlighting the environmental concerns associated with a standard diet and promoting the benefits of a plant-based diet.

“Compared to a vegan diet, eating meat, dairy and eggs uses a lot of water! Animal agriculture is an inefficient use of our precious water, with animal products requiring many times more fresh water to produce compared to the same weight of plant…”

Food: There is, interestingly, significant mention of gluten-free products in relation to this theme. We interpret this finding to be related to the health benefits derived from vegan food, which are likely to be conversed about in tandem with health benefits provided by other food descriptors, including ‘gluten-free’. A number of recipes are naturally alluded to, including homemade brownies.

“Vegan and Buckwheat ice cream in action... From my new book OMG Gluten free Gourmet.”

Try: This theme contains tweets from vegans who are attempting to alleviate the suffering of animals and encouraging others to try plant-based alternatives.

“Ignoring the pain and suffering of others is the cruelest action we can take as conscious beings. We need to be their voice and speak out about this cruelty!!!”

Plant-based: While there are distinct conceptual overlaps between ‘vegan’ and ‘plant-based’, we observe that, more than food, the plant-based theme is significantly associated with skin. Users within this cluster tweet about natural and organic skin care, providing relief for sensitive skin as well as alleviating breakouts/acne/dry skin. They also show interest in cruelty-free products with natural ingredients, particularly cosmetics (such as false eyelashes and make-up). Words frequently used in tweets within this theme include ‘wellness’, ‘health’, and ‘nourishment’.

“SUKIN!! We love a natural skin care brand that’s vegan, cruelty free and carbon neutral”

Among the various food products mentioned, smoothies, acai bowls and Buddha bowls appear to be most popular. There is also considerable discussion of plant-based protein sources (such as brown rice protein or pea protein), including queries in relation to specific protein requirements, as well as comparisons of products (comparing the protein in dairy cheese and vegan cheese). Plant-based milks are a significant topic tweeted about, in relation to protein content and taste (though most of this discussion appears to be positive and is chiefly concerned with a comparison between different plant-based milks).

Down: This theme was mostly negative towards vegans, with several complaints of vegan protests causing chaos in Melbourne’s CBD (Central Business District) and disrupting commutes to work.

“This whole vegan thing in the city is doing nothing but putting a terrible stigma on being vegan. Congrats to the dickheads that are holding up MY work day to force an opinion on everyone.”

There was also agreement among many that vegans should be penalised for trespassing on farms and abattoirs. Comments were made in relation to the self-entitlement of ‘extreme’ vegan activists and opinions were stated that vegans force their beliefs onto others. There were some people who agreed that vegans have the right to protest (even if they were not vegan themselves).

Delicious: The majority of tweets on this theme are related to quick, easy, and healthy meal recipes. Snack and breakfast ideas/inspiration appear to be popular. Raw dessert and chocolate were also of high interest.

“This super quick and easy raw, vegan chocolate truffle, are nourishing yet definitely satisfy the strongest chocolate craving. They make a delicious yet nourishing treat that’s perfect for Christmas.”

Melbourne: Significant anger was expressed towards vegan protestors for disrupting the Melbourne CBD with their activism.

“As much as Vegans claim it’s a ’Peaceful Protest’ Shutting down an entire city is NOT peaceful. Get off the fucking road, idiots #idiotvegans #Melbourne”

Thanks: Tweets on this theme were primarily vegan consumers thanking businesses (for example, Hungry Jack’s—a fast-food franchise) for providing vegan options.

“Loved the staff, the fresh produce and flowers, the vegan products and the quick service at the check-out. Thanks guys!”

Vegans were also thankful to other vegan activists for fighting for justice, for instance, in the Melbourne demonstrations.

Video: A number of videos appear to relate to recipes/food (for example, a video of ‘what I eat in a day’ or videos of someone taste-testing vegan products). There were also a large number of videos providing guidance about becoming vegan, as well as discussions of why someone is vegan or no longer vegan.

“BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO VEGANISM|great video by Madeleine Olivia.”

Auspol: Comments from those in support of veganism were related to fighting for animal rights and climate change.

“If a 15 Year Old Climate Activist Recognises the Importance of Being Vegan, why can’t we... #climatechaos #climatestrike #auspol #politas #climatecollapse #vegan”

Interest was also expressed for a vegan ‘democracy sausage’ provided at polling places for the 2019 Federal Election. On the other hand, there was quite significant hatred towards vegans with their being labelled as ‘terrorists’ and ‘extremist’ and described as people who ‘invade’ farms and disrupt day-to-day routines (with threats from some relating to eating additional meat in front of vegans to upset them and their efforts to reduce the demand for animal consumption). Comments were made to support the Australian Government enacting harsher penalties for vegans trespassing on farms.

Overall, it appears that vegan tweeters (or tweeters supporting the vegan movement) make comments in relation to positive outcomes of their choices (for example, combating the climate crisis or minimising harm to others), whereas non-vegans are quite negative, focusing their attention and efforts on mocking vegans. In light of value proposition formulation for vegan food products, this broad finding suggests that a single value proposition is unlikely to reach both groups simultaneously and that different value propositions are likely to be required to reach these respective groups.

Table 2 evaluates the relationships between the various food-related concepts. The most-related word for each concept is shown together with the likelihood of the concepts co-occurring in the text (represented as a percentage).

From the above table, we observe that ‘dairyfree’ is a prominent word, co-occurring with several food-related concepts, including ‘plant-based’, ‘vegetarian’, ‘healthy’, ‘recipe’, ‘glutenfree’, and ‘raw’. This indicates that dairy alternatives are most frequently discussed within vegan conversations and that they hold good potential for contemporary and future food products. Interestingly, there is considerable mention of skin in relation to concepts such as natural and organic, which may be useful for businesses that are currently (or interested) in the skin-care market, particularly given that there are a number of skin products, such as cleansers, cosmetics, and even sunscreen and tanning lotions, that could be a viable vegan business venture.

5. Discussion

Recent times have seen rapid changes in diets and lifestyles [

44]. In particular, the growth in environmental awareness over the past two decades has led to concerns that have impacted on purchasing decisions [

45]. With countless food-related decisions occurring in distracting everyday contexts, it is not surprising that some of these decisions are automatic, habitual, and subconscious, while others are based on conscious reflection [

46,

47].

Several factors are thought to influence people’s dietary choices, including dietary components, cultural and social pressures, cognitive-affective factors, physiological mechanisms, as well as genetic influences on personality characteristics [

45]. In particular, the triple A factors (affordability, availability, and accessibility) can have a major impact on food decisions [

48,

49]. Research shows that plant-based dieting is a highly multidimensional practice that entails much more than food choices alone, with vegan consumers more likely to view their food choices as a defining feature of their identity [

4].

Interestingly, individuals may draw upon very different motivations in making the same food choices. Segmenting consumers into different groups according to their motives has proven useful for explaining consumer behaviour in the context of food choice in previous studies. The identification of consumer segments is crucial for designing targeted marketing measures and product positioning strategies [

7]. Indeed, it does seem clear from these findings that there are no discrete consumer segments based on dietary choices alone. Those consumers with an interest in foods without any animal products in them may not necessarily identify as vegan and may instead be more interested in the impact of individual animal products on their health (e.g., on the impact of dairy foods alone) but still be interested in consuming meat, or merely be discussing veganism as a ‘lifestyle’ rather than as a diet per se. This particularly shows through in the notable presence of the term ‘glutenfree’ (i.e., gluten-free) in our dataset; the consumption of gluten has little or nothing to do with veganism, yet it is another popular eating trend (which has become associated with ‘clean’ and ‘healthy’ living) and thus was a major topic of discussion on Twitter during the period of study. An alternative reading of this data might suggest that a number of vegans, or people who are talking about veganism, may already be or may be considering cutting gluten from their diet in addition to animal products, given that the two are not incompatible. Given that food marketing and labelling can have a significant influence on consumer decisions [

48], food companies need to understand the similarities and differences in consumption patterns among consumer groups and how they perceive food products to ensure food product development success [

44]. Knowing the main factors underlying consumers’ food choices provides important information for having a better understanding of consumers’ interests and attitudes. This is useful for researchers, producers, and manufacturers, as well as policymakers [

50].

Previous research has found the most important factors relating to consumer food choice to be taste, good value for money, and health [

50]. Other work found differences in motives for food choice associated with sex, age, and income, with ratings of ethical concern increasing with age and being higher among women than men [

45]. The seminal study of [

47], considering the conceptual model of the food choice process, identified a value-negotiation process which involves weighing the benefits of particular choices against the potential risks of bad choices. When such conflicts among values occur, one value typically emerges as dominant. In this study, when price and quality conflicts arose, quality was indicated as the more prominent value. These findings indicate that the negotiation of values is a very important part of the food choice process. They additionally highlight the need to further explore how value hierarchies change, what familiar patterns of value negotiation might occur, what values people associate with food categories, and how food categorizations might change (and how this might then influence the outcome of value negotiations). Ultimately, food choice should be viewed as a complex process with a range of influences and values that are negotiated differently by diverse people in a variety of settings.

Our findings align with other studies, such as [

51], which have shown that there is a close association between vegan foods and individual health or ideas of a healthy ‘lifestyle’ more generally. Previous research into consumer perceptions of vegan food and the cultural positioning of vegan foods [

11] has argued that it is often hard to clearly delineate discrete reasons for people switching to vegan diets because this consumer choice sits at the intersection of a range of concerns that include (but are not limited to) individual health, the environment, and animal welfare. As noted above, it may also be a choice that is paired with other types of diets and trends, such as organic and gluten-free. Interestingly, as our study shows, other product categories besides food are held to be important to consumers of vegan food. Cosmetics emerged as a salient topic of conversation among vegan food consumers, given its alignment with the ethical and lifestyle choices of individuals who consume vegan food. This finding underscores that ethical factors are likely to account for a significant portion of value propositions associated with vegan food—a perceived need that transcends consumers’ views of different product categories.

We are also conscious of different consumer segments that populate the marketplace. Perhaps the broadest delineation for our empirical context is the vegan consumer and the non-vegan consumer. We would anticipate that the value proposition for the former should be different to that for the latter. For instance, we would likely find that animal welfare would be a bigger motivator of vegan food consumption for vegans than for non-vegans. In line with this position, reference [

52] shows that spirituality and certain aspects of animal welfare positively influence non-vegan consumers’ attitudes and intentions to purchase vegan food but that it is their conformity towards growing trends in vegan food consumption that moderate intentions to purchase. Meanwhile, the comparison in [

53] of consumers and non-consumers of legumes (a staple ingredient of the vegan diet) indicated that the latter group was hindered by taste and lack of preparation knowledge and preparation time. This contrasted with the consumer group’s identification of protein and dietary fiber sources as motivations to adopt legumes, as also echoed by the findings of [

54].

6. Conclusions

In this paper we have focused on vegan food (i.e., food containing no ingredient sourced from animals) and the motivations for individuals to select vegan food options for consumption. This is a very important topic in the context of the environmental problems facing our planet, such as global warming and climate change at large. Reported as a more sustainable alternative to the consumption of food produced by contemporary agriculture (i.e., based on meat and dairy products), increasing the consumption of vegan food can help mitigate these grand concerns.

To this end, we focused our analytical lens on the value proposition that is communicated between producers of vegan food and the consumers. As recent studies indicate, e.g., [

55], the subtleties in communicating messages about vegan food to consumers, including the framing of those messages, can play an important role in how these messages are received and, in turn, how they may motivate the consumption of vegan food. In our study, we assert that an effective transition towards vegan food consumption necessitates an effective value proposition, whereby the value proposition embedded in the products aligns well with the expectations of consumers. In lieu of traditional methods of investigation, we acquired a very large dataset from the social media platform Twitter and analysed the textual data to ascertain the predominant themes of conversation taking place around vegan food.

6.1. Implications

Our results show that, in light of the three main drivers for vegan food choice—ethical, personal health, and environmental—surprisingly, we see a limited number of environmental or sustainability motivated tweets. This is a significant finding, as while vegan food consumption is reported to be sustainable, from a value proposition communication point of view, this is not a preferred topic of conversation for consumers. Value propositions communicated with respect to personal health attributes (e.g., dairy free, gluten free, and nutrition), and consumption benefits (e.g., tasty, delicious) are more likely to resonate with consumers and motivate increased consumption while concurrently delivering environmental benefits as a positive side-effect. Furthermore, the polarity of the attitudes and conversations taking place between vegans and non-vegans on Twitter underscores that a single value proposition is unlikely to reach both groups simultaneously and that different value propositions are likely to be required to reach these respective groups.

Our study illustrates the employability and management of technologies, such as social media platforms, in understanding consumers in order to develop offerings that can ultimately deliver sustainable outcomes. Furthermore, the findings from this study are useful for business owners, as they will contribute to their understanding of what consumers value in vegan products. It will also help businesses identify consumer segments within vegan and non-vegan populations, assisting the development of strategic value propositions for their products that reflect the needs and wants of the customer. This is commensurate with prior research that shows the need to communicate value propositions effectively [

20]. The authors claim that high-growth businesses communicate their value propositions much more clearly and succinctly, and this has a direct correlation with financial growth. The study in [

35] supports this notion by stating that, when a firm successfully communicates their value proposition, they will have competitive advantage within the market. We believe that our study contributes to the formulation of effective value propositions by businesses providing vegan food offerings, ultimately helping to alleviate the challenges of contemporary food production by supporting a shift toward more plant-based diets that are more sustainable and healthier.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Our study has empirical limitations which we believe future research could endeavour to address. We encourage future work to undertake a more food-focused analysis, which will remove non-food-related themes from the findings that may presently mask some non-emergent topics. In addition, it is recommended that the sentiment of tweets could be studied to shed further light on ‘how’ individuals converse about vegan food. For example, a Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) tool may be able to capture the emotional tone of the written text. Alternatively, Naive Bayes classifiers may be used in a supervised learning algorithm to calculate the polarity and sentiment of textual data. Sentiment analysis appears to be particularly important, as illustrated by the comparison of tweets using the word ‘vegan’ and those using ‘vegans’ in our study. In this instance we were able to observe a more positive sentiment for users of ‘vegan’ and a more negative sentiment for those using ‘vegans’—a finding resulting from our purposeful separation of the words in our coding exercise. However, other sentimental differences may have been missed in our analysis which could provide valuable insights.

It is also recommended that future research evaluates trends in the data in relation to different time points. For example, monthly or yearly trends to track changes in key themes and concepts could be highly beneficial for businesses given the fast-paced nature of social media. We additionally acknowledge that the market could be segmented to study different consumer groups. While our present study has analysed the market in its entirety, we believe that future research can evaluate the value proposition pertaining to vegan consumers and contrast this with the value proposition of non-vegan consumers. This exercise can be particularly useful for businesses that need to develop and communicate different value propositions for different market segments to ensure better alignments of their offerings. Finally, we believe that our empirical examination can be extended to study value propositions connected with different stakeholders in the ecosystem, in alignment with recent research exploring the uptake of other sustainable foods and beverages, e.g., [

56].