Abstract

Accelerators are specially designed entrepreneurship programs that enable startups to scale up at a fast pace through mentoring, intense consulting, training, and provision of access to business networks. To cope with the challenges of the entrepreneurial process and to access resources to achieve a quick scale-up, sustainability startups need a great deal of support from intermediary organizations. In this study, we examined 7358 social-sustainability startups and 2671 environmental-sustainability startups to understand the factors that influence the probability of a sustainability startup being selected by accelerators. Our main research question was whether previous funding (in the form of equity funding or philanthropic support) received by sustainability startups affects the selection decisions of accelerators. We also investigated how team-related characteristics such as work experience diversity, female startup teams, a team’s passion or commitment, and entrepreneurial experience influence the chances of startups being selected by accelerators. Our data were drawn from the Global Accelerator Learning Initiative (GALI), which was cocreated by the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs and Emory University. The data have been collected from entrepreneurs around the world since 2013. The wave we used included a dataset covering the years 2013–2019. Our results indicate that for both social-sustainability and environmental-sustainability startups, the amount of previous equity funding and philanthropic support received from external funding providers is of critical importance for the startup to be selected by accelerators. We also found that previous funding mediates the relationship between various team-related characteristics and the probability of a startup being selected by accelerators.

1. Introduction

In order to cope with the challenges of the entrepreneurial process and access resources to achieve a quick scale-up, sustainability startups need much support from intermediary organizations. Accelerators seem appropriate organizations to support sustainability startups with formal and informal education, expertise, mentoring, and networking [1]. An accelerator is defined as “a fixed term, cohort-based program for startups, including mentorship and/or educational components, that culminates in a graduation event” [2] (p. 1782). However, our knowledge on what affects a sustainability startup’s probability of being chosen by an accelerator is limited [3,4]. Hence, the factors that affect the positive selection decisions of accelerators while evaluating sustainability startups deserve attention.

Although the research on selection criteria applied by commercial as well as social-impact accelerators has recently increased [4,5,6,7], there are still many gaps to be addressed in the literature. Our understanding of the factors that affect the probability of a sustainability startup being selected by accelerators is very limited [3,4]. One of the gaps in the literature that requires attention is whether accelerators pick the winners. In other words, whether they select the teams that have already attracted equity or philanthropic investment, which signal their economic and social/environmental credibility and legitimacy [3]. Our first research question (stated below) aims to answer this question.

Previous research indicates the importance of team-related characteristics in venture selection for both accelerators and investors or other fund providers. Team characteristics are seen as the signal of how a team is suited to a business idea and how it is reliable and capable of successfully pursuing an entrepreneurial opportunity. Previous research scrutinizing the factors that affect the decisions of equity investors emphasizes the role of team-related characteristics in the selection process [8,9,10,11,12]. However, how certain team-related factors signal the quality and appropriateness of a startup, and how they are interpreted by accelerators has not been scrutinized well in the literature. Our second research question aims to address this gap in the literature. Furthermore, raising funds from resource holders can make these signals broadcasting the quality of entrepreneurial teams more apparent and visible to accelerators [13]. Therefore, the impact of team characteristics on the probability of a sustainability startup being selected by an accelerator can be partially explained by its being found credible and legitimate by other fund providers (research question three). By answering these questions, we aim to contribute to the sustainability entrepreneurship literature as well as the literature on accelerators.

Research question one: Does previous funding received by a sustainability startup influence its chance of being selected by an accelerator? Is the type of previous funding influential on the positive selection decision?

Research question two: How do team-related characteristics such as work experience diversity, female startup teams, a team’s passion or commitment, and entrepreneurial experience influence the chances of a sustainability startup being selected by accelerators?

Research question 3: Does previous funding mediate the relationship between team-related characteristics and being selected by an accelerator?

To answer these research questions, we used the data provided by the Entrepreneurship Database Program at Emory University; supported by the Global Accelerator Learning Initiative The dataset contains information collected from entrepreneurial teams during their application to accelerators and after their application. We used the data collected from entrepreneurial teams during their applications due to the focus of this study. For the sake of answering our research questions, we restricted our sample to for-profit startups aiming to generate social or environmental impact. The data has been collected from entrepreneurs around the world since 2013. The wave we used covered the years 2013–2019.

Our sample consisted of 7358 startups which sought to address a social-impact objective (social-sustainability startups) and 2671 startups which sought to address an environmental impact objective (environmental-sustainability startups). Our dependent variable was a binary variable which indicated whether a startup with a social or environmental impact objective was or was not selected by accelerators. Our independent variables included various team-related factors such as work experience diversity, gender composition, a team’s commitment to pursuing an entrepreneurial solution, and a team’s entrepreneurial experience. Our moderator variable was the amount of equity investment and philanthropic support that had been received and reported by the entrepreneurial teams during their application to accelerators. We analyzed the data using the Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) procedure.

Our results indicate that for both social-sustainability and environmental-sustainability startups, the amount of previous equity funding and philanthropic support received from external fund providers is of critical importance for a startup to be selected by accelerators. As the amount of previous funding a startup raised before the application increases, the probability of its getting a positive selection response significantly increases. Previous funding also mediates the relationship between various team-related characteristics and the probability of a startup being selected by accelerators. Our results also exhibit that both accelerators and external fund providers prefer teams instead of solo entrepreneurs. We also found that all-female social-sustainability startup teams have a better chance of being accepted by accelerators. The all-female makeup of a team increases the probability of a startup being selected by accelerators. However, we did not observe a similar result for environmental-sustainability startups.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

This research aims to investigate the factors that affect an accelerator’s positive selection decision about a sustainability startup. To answer the research questions above, this research combines different theoretical perspectives and research realms on sustainability entrepreneurship, accelerators and their selection process, and finally the selection and screening criteria applied to identify the most promising startups to invest in. Therefore, this background section is organized so as to discuss the relevance of our research into these separate research fields and the theoretical backgrounds that led us to build our hypothesis to address gaps in the literature. Since the definition of sustainability entrepreneurship is critical for this study, Section 2.1 discusses previous literature that has delineated sustainability entrepreneurship and the rationale underlying the importance of accelerators for sustainability startups in coping with the challenges of the entrepreneurial process. Section 2.2 elaborates on the complex relationship between financial support and credibility and the subsequent impacts on startups in the light of an array of literature focusing on the funding, selection, and screening of new ventures and on accelerators. The last subsection reviews previous studies scrutinizing the impact of the team-related characteristics in question on the success of startups in order to hypothesize the relationship between team-related characteristics and the probability of a startup being selected by accelerators.

2.1. Sustainability Entrepreneurship

As the need for creating more sustainable solutions (products or services) increases, new ventures serving sustainable development goals (or sustainability entrepreneurship) are alluring [14] (Hall et al., 2010). Although the attention surrounding sustainability entrepreneurship has been increasing, there is still no agreement on its definition [1,15,16]. Some researchers give definitions for sustainability entrepreneurship in a narrow sense, such as the creation and pursuit of opportunities addressing ecological/environmental issues [1,15,16,17]. Others take all the social and environmental aspects of entrepreneurial actions into account, and include in their definitions those that address ecological or social issues [15,18]. Patzelt and Shepherd [18] (p. 632) define sustainable entrepreneurship as “the discovery, creation, and exploitation of opportunities to create future goods and services that sustain the natural and/or communal environment and provide development gain for others”.

Developing a working business model is important for commercial as well as sustainability startups. A business model combines all resources and activities that support an organization to create, deliver, or capture value [19]. Sustainable organizations need to build their business models so as to create, deliver, and capture both commercial and social or environmental value [20,21]. Such startups may encounter many difficulties in attracting different stakeholders, since they have to deal with two different realms governed by different institutional logics [22]. Furthermore, it may be difficult for them to mobilize financial resources [23,24]. Being selected and nurtured by accelerators helps such startups to overcome such constraints and challenges and to rapidly scale up and achieve their economic and sustainability goals [25,26]. Therefore, studying the factors that affect a sustainability startup’s chance of being selected by accelerators deserves attention and has theoretical as well as practical implications. For example, being informed about the factors that affect accelerators’ selection decisions can allow startups to manage their resources to create a positive impression on accelerators and increase their chance of being selected; thus, they can access accelerators’ resources to survive and scale up.

2.2. Startup Selection by Accelerators and the Role of Previous Funding

Recently, the research on the selection and screening processes of accelerators has been growing, providing a more concise review of the criteria applied by accelerators to select startups [4,5,6,7]. These studies reveal that accelerators consider both business-project-related factors and the characteristics, skills, and competences of startup teams [4,5,7].

However, to the best knowledge of the authors, only a few studies have discussed the impact of previous funding raised by startups before their applications to accelerators on the probability of their being selected by accelerators [3]. This question is important for understanding whether accelerators pick the winners, or in other words, the startups that have already attracted investors or other resource holders and have thus been evaluated as appropriate and eligible by them. Previous funding can be interpreted as a signal of a startup’s credibility in the eyes of external evaluators [3].

The impact of third-party endorsements on the positive selection of startups by private equity investors has been studied by previous research [13,25,27]. The positive impact of such endorsements can be explained by the contribution of third parties to the value creation process [25,26,28]. Others intent to explain this phenomenon through the signaling theory and emphasize the power of being selected by third parties as a credibility signal [13,27]. Gubitta, Tognazza, and Destro [27] suggest that by being funded by TTOs, new ventures send a positive signal to venture capital firms (VCs) about their quality. Thus, third-party endorsements (especially funding from other financiers) work as positive signals that broadcast the quality, credibility, and future promises of startups [3,13,27,29,30].

Studies that focus on the impact of previous funding raised by startups on their chance of being selected by accelerators are very scarce [3]. One reason might be that accelerators generally attract nascent startups which have not yet accessed external funding and aim to build them to raise funding from investors or other resource holders. This assumption might emerge from a view that identifies accelerators with other entrepreneurship support organizations (e.g., incubators) or recognizes them as a new form of incubation. However, accelerators are different from other organizations in terms of their selection practices, value creation processes, and the services that they provide to startups [31,32,33,34,35]. Recent research suggests that the mechanisms used by accelerators to add value to startups are also different to those used previously [31,32,33].

One mechanism that is critical for accelerators is the quick validation of product–market fit [26,32]. Stayton and Mangematin [33] suggest that accelerators reduce the time that passes from an entrepreneurial idea to value capture. By intensive focus on experimentation for the validation of product–market fit and scalability options, accelerators quickly resolve uncertainties around startups, and this leads to quick failure or rapid scalability [26,32]. In such a context, previous funding might work well as a strong signal of the validity of a startup’s value proposition and shorten the time needed for testing the product–market fit. Additionally, previous funding helps startup teams to finance the product concept development and prototyping activities, and hence apply an accelerator with more mature products [7]. Because of these two factors, selecting startups which have been previously funded aligns well with the objectives and mechanisms of accelerators. Therefore, we expect that accelerators tend to select startups which have already raised funding from external resource holders either in the form of equity investment or philanthropic support.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Accelerators are more likely to select sustainability startups that have raised equity investment.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Accelerators are more likely to select sustainability startups that have raised philanthropic investment.

2.3. Startup Selection by Accelerators and the Role of Team Characteristics

Team-related characteristics are strictly reviewed by accelerators while making their selection-decisions [5,7]. In this research, we studied the impact of four team-related features on accelerators’ decisions: work experience diversity, gender, commitment/persistence, and experience.

A quick scale-up requires the embodiment of a varied set of skills within new venture teams. Education, training, and work experience influence the extent of information that individuals have access to and their way of processing information [36]. Teams that combine different perspectives by bringing together individuals who have access to different kinds of information and process and interlink that information in different styles exhibit higher levels of creativity and capacity for innovation [37,38].

Being run by a team instead of a solo entrepreneur can ensure such diversity. Previous research indicates that teams that bring together various individuals are more successful than solo entrepreneurs [39] due to the fact that teams “generally have a larger and a more diverse array of human capital than a venture associated with a solo entrepreneur” [40]. Recent research on the selection process of accelerators indicates that being run by teams instead of solo entrepreneurs is considered as an important selection criterion [4,5,6]. Therefore, we expect that accelerators tend to select startups that are run by teams instead of solo entrepreneurs.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Accelerators are more likely to select sustainability startups run by teams instead of solo entrepreneurs.

Having different types of experience is also critical for the success of new ventures. For instance, a diversity of industry and entrepreneurial experience has a positive effect on entrepreneurial performance [41]. Entrepreneurs must combine different skills and abilities to start and run a new business in a successful way; therefore, entrepreneurs who have worked in various roles are more likely to start their own business [42]. The jack-of-all-trades theory of entrepreneurship [42] indicates that “having a background in a large number of different roles increases the probability of becoming an entrepreneur” [43]. Previous research supports this perspective and reveals that there is a positive relationship between having balanced and diverse work experience and the probability of being an entrepreneur [43,44]. Therefore, we expect that accelerators tend to select startups that are run by entrepreneurs who have diverse work experience.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Accelerators are more likely to select sustainability startups that are run by entrepreneurs who have diverse work experience.

A diversity of work experience and a team-led structure are evaluated as positive signals of the future performance of startups. Hence, they are considered to be one of the most important criteria by external funding providers while selecting early-stage startups. It can be argued that when diversity in work experience is appreciated and rewarded by external resource holders, these signals can be more apparent to accelerators and influence their selection decisions. Therefore, we hypothesize that previous funding mediates the relationship between the work-experience diversity of entrepreneurs and their being selected by an accelerator. The same relationship can also be hypothesized between the presence of a team and a startup being selected by an accelerator (these hypotheses are given in Appendix A).

In terms of startup selection, previous research exhibits that female-led new ventures are undervalued by external evaluators, especially by external fund providers, due to the gender stereotype bias which obscures the value of some positive signals given by female entrepreneurs or teams [45,46,47,48,49]. Many studies admit that female entrepreneurs’ lower access to external financing originates from the gendered preferences of investors or other resource holders [46,50,51]. Female teams are seen as less legitimate than male teams [46]. Thus, they have less access to external funding resources provided by angel investors and venture capital [48,50,51]. Even though they do access external funds, they receive funds with a lower valuation, and therefore need to offer higher equity stakes for less investment than their male counterparts [47].

However, gender role congruity theory focuses on the match or mismatch between displayed stereotypical gender behaviors and the gender role that is dominant in the given context. Therefore, both males and females can experience the negative and positive implications of gender role incongruity in various contexts [3,45]. This indicates that if female entrepreneurs broadcast signals which are congruent with their gender role they can be favored by external evaluators [3]. Emphasizing the social and environmental benefits of a new venture for female entrepreneurs signals gender role congruity, and therefore helps them to receive more acceptance from stakeholders [3,52]. The underlying reason might be that engaging in social value creation activities is seen as culturally more appropriate for female entrepreneurs and aligns with their gender role [53].

Recent research suggests that framing the value created by new ventures by emphasizing social and environmental benefits mitigates the gender-related penalties that female entrepreneurs experience while they are seeking support from external parties such as fund providers, incubators, or accelerators [3,52]. Therefore, we can expect that being run by female entrepreneurs increases the probability of a sustainability startup being selected by accelerators.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Accelerators are more likely to select sustainability startups that have been formed by female entrepreneurs.

Yang, Kher, and Newbert [3] found that the gender of the founders influences the economic and social credibility signals broadcast by previous equity and philanthropic funding. However, it can also be argued that being found credible by external resource holders may influence the way the gender of the team/entrepreneur signals to accelerators. In other words, accelerators may accept sustainability startups when their gender role is viewed by external fund providers as congruent to the entrepreneurship realm (please see Appendix A for hypotheses).

Passion is “a strong indicator of how motivated an entrepreneur is in building a venture, whether she/he is likely to continue pursuing goals when confronted with difficulties” [54] (p. 199). Entrepreneurial passion or how it is demonstrated by entrepreneurs and how it is perceived by external audiences are among the factors which influence the interest of investors in startups, especially at early stages [54,55]. Ko et al. [56] prove that social entrepreneurship passion increases the social innovation performance. Passion demonstrates itself in the form of commitment and persistence [57,58].

According to Busenitz, Fiet, and Moesel [59], entrepreneurial teams can communicate their commitment by investing their own wealth in their venture; such an investment also shows how much the team believes in the potential of their entrepreneurial project. Nascent entrepreneurs who invest their own money in their ventures not only display their commitment, but are also more likely to be successful and less likely to disengage from the entrepreneurial process [60]. When we consider the relationship between entrepreneurial passion, commitment, and the use of personal wealth to finance ventures, we expect that accelerators tend to select founders who invest their own money into their entrepreneurial projects.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Accelerators are more likely to select sustainability-startup teams that invest their own money in their ventures.

Since understanding the passion and commitment of entrepreneurial teams is critical but at the same time difficult to achieve for accelerators, as well as other external fund providers, previous funding received by startups may mediate the relationship between the entrepreneurial passion/commitment and the probability of a startup being selected by accelerators (for related hypotheses, please see Appendix A).

The impact of founders’ ages on entrepreneurial activities has not been studied much in the literature [61,62]. However, the success of startups such as Google, Facebook, and Instagram, created by student entrepreneurs at very young ages, also empowers the perception that new venture creation is “a young man’s game” [61] (p. 177). One reason that entrepreneurship is more attractive to young people might be that, since they do not have full-time jobs, they can commit most of their time to creating a new venture [61]. They do not need to risk losing a full-time job to start a new venture; they can more easily seize the entrepreneurial opportunities brought by new technologies; they are more flexible and open to experimentation; and they do not fear failure. These are also critical features for employing a lean startup methodology [63]. Moreover, younger people without a full-time job commitment can benefit more from training, mentoring, and networking support and dedicate much of their time to developing their business; thus, their business can quickly scale up. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Accelerators are more likely to select sustainability startups created by younger founders.

Age and experience can be seen as interlinked. Previous research exhibits that angel investors and VCs consider the industry experience of founders to evaluate how an entrepreneurial team fits to its business idea [64,65]. However, the entrepreneurial experience may have a greater impact on the early performance of startups than industry experience, because “the best way to learn about making a company successful is … to run a new firm” [66] (p. 151). Recent research reveals that the founding experience of entrepreneurs influences VCs’ decisions in the first round of investment [67,68]. Previous entrepreneurial experience may influence the decision of accelerators, because entrepreneurial learning is based on learning-by-doing and therefore such entrepreneurs are more knowledgeable about the requirements of the entrepreneurial process. Therefore, we can expect that the entrepreneurial experience of a startup team positively influences the probability of a startup being selected by accelerators (H8). We also expect that previous funding mediates the relationship between age as well as entrepreneurial experience and the probability of a startup being selected by accelerator (for hypotheses Appendix A).

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Accelerators are more likely to select sustainability startups whose founders have entrepreneurial experience.

3. Data and Methodology

In this study, we used the Global Accelerator Learning Initiative (GALI) dataset, which consists of information for both accelerators and entrepreneurs. We used the latter due to the focus of this study. The Entrepreneurship Program was developed at Emory University and has been collecting data from entrepreneurs around the world since 2013. The wave we used included panel data covering the years 2013–2019. The dataset contains data on more than 23,000 ventures that applied to acceleration programs all around the world. In this study, we restricted our sample to for-profit startups that addressed at least one social or environmental impact objective, and examined the impact of team-related characteristics on the probability of a sustainability startup being selected by accelerators, as well as the mediation effect of previous equity and philanthropic investment on the relationship between team-related characteristics and the probability of being selected by accelerators. All missing values were eliminated from the sample. Moreover, to achieve normality condition, values were transformed into log values where possible.

3.1. Sample Selection

In order to identify sustainability startups that addressed environmental or social impact objectives, we followed the procedure proposed by Giones, Ungerer, and Baltes [69]. In the questionnaire survey, the applicants were asked to indicate up to three impact objectives that their startups were seeking to address. The list of impact areas included in the survey and their classifications as either social- or environmental-sustainability impacts are given in Appendix B (Table A2). The applicant startups that checked one of the impact objectives classified as a social-sustainability impact were identified as social-sustainability startups, and those that checked one of the impact objectives classified as an environmental-sustainability impact were coded as environmental-sustainability startups. Finally, we identified 2671 startups in the dataset as environmental-sustainability startups and 7358 startups as social-sustainability startups.

3.2. Dependent Variable

We followed the literature in deciding dependent variables to use in this study [3]. Our dependent variable was whether or not a sustainability startup was accepted by the accelerator to which the startup had applied. It was a binary variable. It was coded 1 if the startup had been selected and 0 otherwise (Table 1).

Table 1.

Dependent and independent variables.

3.3. Independent Variables

The survey covered data concerning startup profiles, such as the size of founding team, age of founders, gender composition of founding team, entrepreneurial experience of founders, the amount of founders’ own investment into entrepreneurial project, job roles that each founder occupied, and the amount of equity investment and philanthropic support received and reported during the application to accelerators. Table 1 presents a description of explanatory variables. Table 2 demonstrates the results of summary statistics.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics.

3.4. Empirical Analyses

In this study, we used mediation analysis to examine the effects of factors on accelerators’ selections and whether these effects were mediated by previous equity financing or previous philanthropic support. Therefore, we analyzed both direct and indirect effects. First, we obtained the direct effect of the explanatory variables on the dependent variable. Second, we checked whether the relation between the explanatory variables and dependent variable was mediated by the selected treatment variable.

There are various approaches regarding mediation analysis [70,71,72,73]. In this study, we used a very recent statistical package developed by Mehmetoğlu [74]. It is a Stata package named medsem that provides a postestimation command testing mediational hypotheses following Baron and Kenny’s [75] approach. Although we admitted that older statistical packages were useful, we preferred this method since it would enable us to run all direct and indirect estimations simultaneously. In addition to this, older packages follow the regression approach for estimations, which results in larger standard errors. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) procedure, on the other hand, does not produce these errors.

Under the framework of SEM, in this research, two variables (i.e., previous equity investment and previous philanthropic support) were chosen as mediators. To analyze the mediating effect of previous equity investment and previous philanthropic support on the relationship between various independent variables and the dependent variable of being selected by accelerators, we followed the procedure in [74] for testing mediation. It is composed of four separate steps to achieve complete mediation.

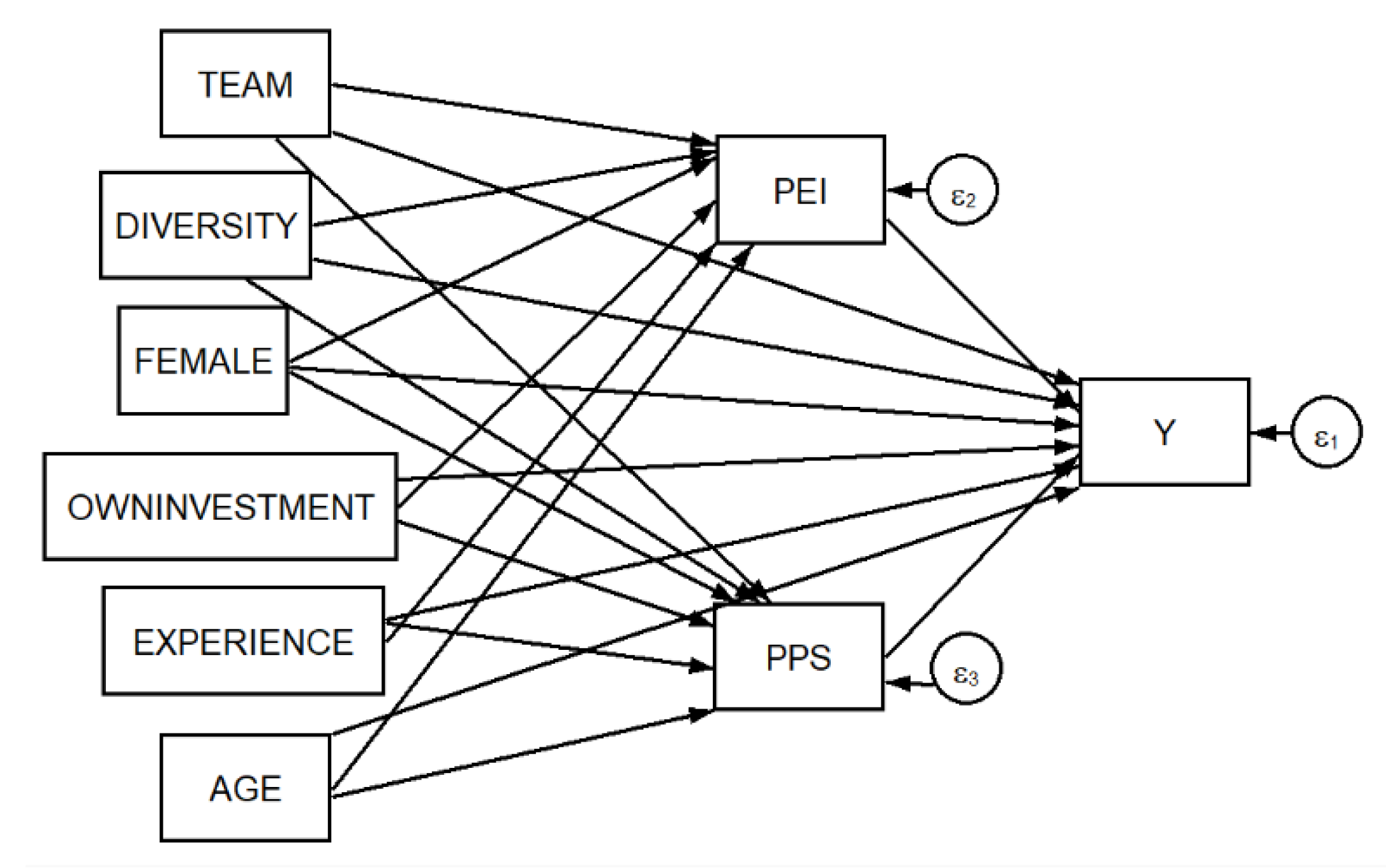

Accordingly, we regressed Y (selection decision of accelerator) on X (TEAM, DIVERSITY, FEMALE, OWN INVESTMENT, AGE, EXPERIENCE) separately to estimate any direct effect:

Y = β_0 + cX + Ɛ

Then, we regressed PEI (M1) and PPS (M2) on X variables:

M = β_0 + aX + Ɛ

A further step included regressing Y (selection decision of accelerator) on M (PEI and PPS) by controlling the effect of X variables:

Y = β_0 + bM + c’ X + Ɛ

To claim that M completely mediates the X–Y relationship, the effect of X on Y controlling for M should be zero. If all four steps are met, one can claim that M completely mediates the relationship between X and Y.

However, if the first three steps are met but step four is not met, we can say that there is a partial mediation. Alternatively, Mehmetoğlu [74] applied a modified version making small improvements on Barron and Kenny’s approach, which is based on a regression technique and generates larger standard errors [76]. Contrary to regression analysis, SEM technique generates more consistent results.

By following Mehmetoğlu [74], we simultaneously estimated both direct and indirect paths, shown in Figure 1. Accordingly, when both X → M and M → Y coefficients were significant, we applied further steps. Then, we ran Sobel’s z to test the relative sizes of the mediated paths versus direct paths. Depending on the test results, we found different scenarios. If the z score was significant and the direct path between X and Y was not, the mediation was complete. If both the z score and the direct path were significant, a partial mediation was observed. Additionally, if the z was not significant but the direct path X → Y was, the mediation was partial in the presence of a direct effect. Finally, if neither the z nor the direct path X → Y was significant, the mediation was partial in the absence of a direct effect. For each situation, we reported ‘no’, ‘partial’, or ‘full’ mediation. The path analysis was also estimated to test the model validity. According to the results of the goodness-of-fit statistics, the model provided close fitting. As for the chi-square value (36.796, p > chi2 = 0.000), we found that the chi-square goodness-of-fit test provided significant results which indicated a poor model fit. Deciding on the model validity based on this value, on the other hand, would not be an appropriate strategy. Instead, further goodness-of-fit statistics were considered. Accordingly, lower values of RMSEA were used as an indication of good model fit. In this study, we obtained RMSEA = 0.070, which was acceptable [77]. Additionally, the comparative fit index (CFI) was about 0.92, which provided an acceptable value for goodness of fit.

Figure 1.

Model Building.

4. Discussion of Results

In this section, the estimation results for social- and environmental-sustainability startups will be discussed separately. First, we will focus on social-sustainability startups and the factors that influence their probability of being selected by accelerators.

4.1. Social-Sustainability Startups

Results from the regression analysis indicate that both equity financing and philanthropic support (PEI and PPS) received and reported during the application process have a significant and positive impact on the probability of a social-sustainability startups being selected by accelerators (Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimation results for social-sustainability startups.

In Model (1) and Model (2), two explanatory variables, TEAM and FEMALE, were shown to have significant effects on both the amount of previous funding raised from external resources by social-sustainability startups and the dependent variable of the probability of being selected by accelerators. TEAM positively and significantly affected PEI as well as the startup being selected by accelerators. The effect of FEMALE on PEI was significant but negative. On the other hand, its effect on the dependent variable of being selected by the accelerator was significant and positive. In other words, social-sustainability startups that are run by all-female founders have a lesser chance of attracting equity investment from external resources but have a higher probability of being selected by accelerators. Moreover, AGE positively affected PEI raised by social-sustainability startups. EXPERIENCE had a similar effect on PEI. Similarly, OWN INVESTMENT and DIVERSITY had positive and significant effects on PEI raised by social-sustainability startups.

Model (3) and Model (4) included the amount of previously received philanthropic support (PPS). Model (3) indicated that PPS, TEAM, and FEMALE had a significant and positive impact on the probability of a social-sustainability startups being selected by accelerators. Two variables, TEAM and OWN INVESTMENT, influenced both PPS and the probability of a startup being selected by accelerators significantly and positively. OWN INVESTMENT increased the amount of philanthropic support (PPS) as well as the probability of being selected by accelerators. However, AGE negatively correlated with PPS but had no effect on the probability of being selected by accelerators. To be run by all-female founder teams positively and significantly influenced a social-sustainability startup’s probability of being selected by accelerators. DIVERSITY positively affected PPS but had no significant effect on the selection decisions of accelerators. Table 4 shows the list of hypotheses and decisions. Additionally, mediation effects of PEI and PPS for independent variables are demonstrated in Table 5.

Table 4.

Decisions about hypotheses for social-sustainability startups.

Table 5.

Mediation effect of previous equity funding between independent variables and dependent variable for social-sustainability startups.

We ran SEM to analyze the mediation effects of PEI and PPS on the relationships between team-related characteristics and the dependent variable. The first explanatory variable was TEAM. Table 6 demonstrates the Sobel test results of the mediation analysis, which included three steps. In the table, the first step shows the relation between the related variable (X) and the mediator (M) using the coefficient and its significance level. The second step exhibits the relation between the mediator (M) and the dependent variable (Y). In the table, the third step only exists for cases where the first two steps provided significant effects.

Table 6.

Test results of mediation analysis for social-sustainability startups.

According to the results of the mediation analysis, we observed a positive and significant effect of TEAM on M1 (PEI) (see Table 6). Further, the effect of TEAM on the dependent variable (being selected by accelerators) was also positive and significant. For this case, there was a partial mediation. FEMALE had a positive and significant effect on both PEI and the dependent variable of being selected by accelerators. Thus, we could conclude that the effect of having an all-female founder team on the probability of a social-sustainability startup being selected by accelerators was partially mediated by PEI.

Moreover, our estimation results exhibit that EXPERIENCE significantly affected the mediator while it did not generate any significant effect on the dependent variable. In other words, the effect generated by EXPERIENCE was mostly based on the mediator. We also found that the effect of OWN INVESTMENT on the probability of being selected by accelerators was mediated by PEI. Finally, DIVERSITY had a partial mediation, while there was no mediation for AGE.

As for the estimations regarding the mediation effect of PPS, our results indicate a partial mediation effect of PPS on the relationship between TEAM and the probability of a social-sustainability startup being selected by accelerators. AGE had a significant and positive effect on the mediator but not on the dependent variable. However, the mediator had a positive and significant effect on the dependent variable. Thus, it can be concluded that there was a complete mediation. Twenty-two percent of the effect of AGE on being selected by accelerators was mediated by PPS. According to the results we obtained, the effect of OWN INVESTMENT on the probability of a startup being selected by an accelerator was completely mediated by PPS. Finally, our results indicate that PPS had no mediation effect on the relationship between two explanatory variables (FEMALE and EXPERIENCE) and the dependent variable.

4.2. Environmental-Sustainability Startups

We also examined the factors that influence environmental-sustainability startups being selected by accelerators. Our regression results, shown in Table 7, indicate that the PEI and PPS received by environmental-sustainability startups had significant and positive effects on the probability of these startups being selected by accelerators. The results also showed that TEAM and DIVERSITY had significant and positive effects on the probability of such startups being selected by accelerators. However, TEAM and DIVERSITY had no significant effect on PEI.

Table 7.

Estimation results for environmental-sustainability startups.

On the other hand, AGE, EXPERIENCE, and OWN INVESTMENT had a significant and positive impact on the PEI raised by environmental-sustainability startups. However, these variables had no direct significant effect on the probability of these startups being selected by accelerators. The regression results also exhibited that AGE negatively correlated with the amount of philanthropic support received by environmental-sustainability startups (PPS). As AGE increased, the amount of philanthropic investment decreased. However, OWN INVESTMENT positively and significantly correlated with PPS. Table 8 reveals the hypotheses and decisions. Moreover, mediation effects of PEI and PPS are shown in Table 9.

Table 8.

Decisions about hypotheses for environmental-sustainability startups.

Table 9.

Mediation effect of previous equity funding between independent variables and dependent variable for environmental-sustainability startups.

We conducted mediation analysis to understand whether the PEI raised by environmental-sustainability startups had a mediation effect on the relationship between the team-related characteristics and the probability of such startups being selected by accelerators. We observed no mediation effect of the amount of equity financing on the relationship between four explanatory variables (DIVERSITY, TEAM, FEMALE, and AGE) and the dependent variable. However, we observed a significant relationship between EXPERIENCE and PEI, and a significant and positive relationship between PEI and the dependent variable. We can therefore suggest that there was a complete mediation. We also found that the effect of OWN INVESTMENT on the dependent variable was mediated by PEI.

For startups that seek to address an environmental impact objective, we also conducted mediation analysis by using a second mediator, PPS. We observed its mediation effect on the relationship between two explanatory variables (i.e., AGE and OWN INVESTMENT) and the dependent variable of an environmental-sustainability startup being selected by an accelerator.

4.3. Robustness

To check the robustness of our results, we conducted an alternative mediation analysis developed by Hicks and Tingley [72], who applied the medeff command. To apply this, we first used TEAM as the treatment variable and examined its effects on the selection decision of accelerators and checked whether the relation between TEAM and the selection decision of accelerators was mediated by PEI and PPS. In Appendix C, Table A3 demonstrates the estimation results for social-sustainability startups. Accordingly, the average causal mediation effect (ACME) of the variable for the model where PEI was the mediator was found to be approximately 0.001, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.001–0.003. Since the value was within this range, we concluded that the mediation was significant; however, it was quite low. This result was consistent with our model reporting partial mediation for TEAM (see Table 6). The average direct effect (ADE) of TEAM on the selection decision of accelerators was estimated as 0.062 (0.037–0.085), which was consistent with the coefficient of TEAM in our model (see Table 3). We therefore concluded that TEAM increased the probability of a social-sustainability startup being selected by accelerators, but that this effect was partially mediated by PEI. Additionally, we obtained similar results for the model where the mediator was PPS. The results for other variables can be found in Table A3.

We repeated the same model for environmental-sustainability startups (Appendix C, Table A4). Accordingly, the ACME of the variable for the model where PEI was the mediator was about 0.0009, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.001–0.003. This indicated that the mediation was insignificant. Again, this result was consistent with our model reporting no mediation for TEAM (see Table 10). The average direct effect (ADE) of TEAM on the selection decision of accelerators was estimated as 0.059 (0.015–0.10), which was consistent with the coefficient of TEAM in our model (see Table 7). We therefore concluded that TEAM increased the probability of an environmental-sustainability startup being selected by accelerators, but that this effect was not mediated by PEI. We obtained similar results for the model where the mediator was previous philanthropic support. Table A4 shows the results for other variables.

Table 10.

Test results of mediation analysis for environmental-sustainability startups.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Key Findings and Theoretical Contribution

In this research we investigated: (1) how previous funding received by sustainability startups in the form of equity funding or philanthropic support influences the probability of their being selected by accelerators; (2) how team-related characteristics such as the presence of a team instead of solo entrepreneurs, the work experience diversity of teams, the gender composition of teams, the age and experience of the founders, and their commitment to the entrepreneurial project (measured by their own investment) influence the positive selection decision of an accelerator; and finally (3) whether previous funding received by startups mediates the relationship between team-related characteristics and a startup being selected by accelerators.

Our results exhibit that for both social-sustainability and environmental-sustainability startups, the amount of previous equity funding and philanthropic support received from external fund providers is very important for selection by accelerators. As the amount of previous funding a startup has raised before the application increases, the probability of its receiving a positive selection response significantly increases. For startups, raising equity funding or philanthropic support is a strong signal of their being seen as credible and legitimate by external funding providers [3,27,78]. New ventures face the “liability of newness” [79] (p. 148) due to their lack of history and uncertainties about the viability of their entrepreneurial projects, technology, and markets. In order to cope with the liability of newness, startups need to be seen as legitimate and appropriate. New ventures can gain legitimacy through acceptance, and hence they can obtain access to resources they need to survive and grow [80,81]. Since such startups need to be accepted as profit-seeking new ventures as well as creators of social and environmental value, they must deal with the institutional logics of these two different realms [22]. Therefore, raising funding and receiving support from external resources can be seen as a strong signal of their credibility and legitimacy as sustainability startups. Our results align with the results presented by Yang, Kher, and Newbert [3] in their recent study on social impact accelerators: previous funding signals the credibility of the startups and increases the probability of their being selected by accelerators. However, beyond this recent study, our research suggests that not only having access to previous funding but also the amount of funding positively correlates with the positive selection decisions of accelerators.

Additionally, early-stage funding and financial support may help sustainability startups to improve their products/services and enlarge their teams and human capital [29]. Research on accelerators’ selection and screening processes and the criteria they use while making their acceptance decisions indicates that product/concept maturity and the validation of demand are very critical for commercial and social impact accelerators [4]. Previous equity funding and philanthropic support help sustainability startups to improve their products, test their business model, and validate the demand in the market. Hence, they can scale up very quickly with the intense support and services provided by accelerators; they can then benefit more from accelerators and their support.

Our results also indicate that the presence of a founding team is very critical for both social-sustainability and environmental-sustainability startups when seeking acceptance by acceleration programs as well as financial support from external resources. Accelerators as well as external fund providers prefer teams instead of solo entrepreneurs. This may be explained by the complexity and demanding requirements of developing a business that seeks profit but also aims to uphold social and environmental values. This process also requires different sets of skills, expertise, and experience. Our results are also consistent with a previous research work showing that entrepreneurial teams are more successful than solo entrepreneurs [39] and with a recent research work investigating social-impact accelerators’ selection processes [4]. The authors argued that “impact accelerators seem to put more focus on the size of the teams” and this can be explained by the fact that “sustainability entrepreneurship requires not only business expertise, but also skills from other fields including natural and environmental sciences, engineering, or social sciences” [4] (p. 14).

We also found that all-female social startup teams have a better chance of being accepted by accelerators. The all-female makeup of a team increases the probability of a startup being selected by accelerators. However, we did not observe a similar result for environmental-sustainability startups. Our results also show that an all-female composition of a startup team negatively correlates with the amount of previous equity funding raised from external resources. Social value creation activities are seen as culturally more appropriate for female entrepreneurs and align with their gender role [53], and therefore the probability of their being selected by accelerators increases. Our results confirm previous studies that suggest that when female entrepreneurs broadcast signals which are congruent with their gender role, they are favored by accelerators [3]. However, the results also emphasize the gender role bias against female entrepreneurs, because sustainability startups run by all-female teams raise less equity funding from external resources. We reached a similar conclusion to previous studies suggesting that female entrepreneurs have less access to external funding provided by angel investors and venture capital [48,50,51].

We also found that the amount of money invested by founders to their entrepreneurial project has no direct effect on the selection decisions of accelerators. However, it does affect the probability of a startup being selected by accelerators by way of previous equity funding and philanthropic support. The underlying reason might be that founders who invest their own money into their projects are more passionate about their projects, commit their time and effort to the project, and are more engaged and perseverant. Therefore, they are evaluated as more appropriate for the startup acceleration process based on their improved products, already validated value propositions, and well-prepared business plans. Although previous studies [59,60] do not reveal a direct relationship between the amount of personal investment and the attraction of external investment, our results point out a significant and positive relationship between internal and external funding.

Another interesting finding about sustainability startups is that both the age of the founders and the entrepreneurial experience of the founders have no direct effects on the probability of the startup being selected by accelerators. However, the relationship between these two variables and the dependent variable is mediated by previous external funding. The impact of founders’ average age on whether a startup is selected by accelerators is mediated by philanthropic support, whereas the relationship between the founders’ entrepreneurial experience and their being selected by accelerators is mediated by previous equity funding. Our results indicated that the average age of the founders negatively correlates with the amount of philanthropic support. On the other hand, the entrepreneurial experience of the founders does not have a direct effect on startups being selected by accelerators, but it does influence the chance of selection by way of the amount of equity funding raised from external resources. Equity funding providers prefer to invest in startups created and run by experienced entrepreneurs.

Sustainability startups need to create commercial and social or environmental value. Therefore, they need to cope with two different institutional logics. This may hamper their attempts to gain credibility and legitimacy in markets and may decrease their access to external financial support, which is necessary for a quick scale-up [1,22,23,24]. Being nurtured by accelerators may help sustainability startups to overcome these obstacles and support them to achieve rapid scalability. By focusing on the impact of previous funding and team-related characteristics on the selection decisions of accelerators, our research reveals that previous financial support, either in the form of equity funding or philanthropic support, has a significant impact on accelerators’ selection decisions. Moreover, these two forms of financial support not only have a direct impact on selection decisions, they also mediate the relationships between various team-related characteristics (age, experience, and passion/commitment) and the probability of a startup being selected by accelerators. The results indicate that startup selection is a complex process and it should be scrutinized extensively in the case of sustainability startups.

5.2. Managerial and Policy Implications

While contributing to the theoretical understanding of the factors that affect the chance of sustainability startups being selected by accelerators, we believe that our research also has some practical implications for the entrepreneurs of sustainability startups and the executives of accelerators. Sustainability startups can use our results to better understand which team-related factors influence their chance of being selected by accelerators and of accessing equity funding or philanthropic support. Thus, they can manage their resources to create a positive impression on accelerators and external supporters and broadcast positive quality signals to external evaluators. External support is critical for sustainability startups seeking to acquire the necessary resources to survive and scale up rapidly. Our results may also have managerial implications for the executives of accelerators. They can review and revise the criteria that they use to select the most promising sustainability startups to nurture. By considering the challenges that sustainability startups confront in gaining credibility from external fund providers, accelerators may prefer to change their selection and screening procedures and criteria so as to support sustainability startups. Thus, it would be beneficial for accelerators to be self-reflective about their selection procedures and revise them to ensure the acceptance of more startups with social- or environmental-sustainability impact goals.

The need for sustainable solutions (products and services) and the role of sustainability entrepreneurship in developing these solutions are undeniable. Policies to support entrepreneurial activities should be reconsidered and revised so as to support sustainability entrepreneurship. Our results may also have policy implications, encouraging the re-evaluation of the appropriateness of acceleration programs for sustainability startups and, if necessary, the design of new support mechanisms to encourage sustainability entrepreneurship and to provide startups with what they need to survive and scale up quickly.

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

Our study provides valuable insights into the impact of previous funding and several team-related characteristics on the probability of a sustainability startup being selected by accelerators. However, the limitations of this study should also be kept in mind while interpreting the results. Some of these limitations are related to the sample selection process we applied. First, in this research, sustainability startups were selected based on their self-identified impact objectives; applicants that checked one of the social impact objectives were classified as social-sustainability startups, and those that checked one of the environmental impact objectives were classified as environmental-sustainability startups. Therefore, the extent to which the startups in the sample were committed to their sustainability goals cannot be detected. The degree of the startups’ commitment to their sustainability goals may have affected their probability of being selected by accelerators and the impact of the explanatory variables on the selection. Second, the data we used did not include any specific information about the accelerators, i.e., whether or not an accelerator was a social-impact accelerator. Social-impact accelerators, although they exhibit some similarities in selection criteria, may value the social impact objective of applicants to a greater extent than general-purpose accelerators. We can also expect that the second limitation is linked to the first. Startups that prefer to apply to impact-oriented (social or environmental) accelerators are expected to be more committed to their sustainability goals. Future research should take into account these variances among sustainability startups and their accelerators to better scrutinize the factors that affect the probability of a startup being selected by an accelerator.

The selection of the most promising startups to be nurtured by accelerators is a complex process. Accelerators also consider entrepreneurship-project-related factors such as the concept maturity, the validity of the project idea, the value proposition, the size of the market, and the business model [4,5,6,7]. In this research, we focused on team-related characteristics and their impact on the positive decision of accelerators. It can be expected that there is strong interconnection between team-related factors and project-related factors. For instance, entrepreneurial experience or receiving previous funding are expected to influence the product/concept maturity, the effort spent on testing the validity of the business ideas, the business models, and many other project-related factors. We can advise future researchers to focus on the impact of project-related factors, the interaction between team-related factors and project-related factors, and their combined effect on the positive selection decisions of accelerators. Such research will contribute to our theoretical understanding of the factors that trigger a positive assessment of sustainability startups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B.; methodology, D.F. and B.B.; formal analysis, D.F.; validation, D.F.; software, D.F. and B.B.; investigation, B.B. and D.F.; writing—original draft, B.B. and D.F.; writing—review and editing, B.B. and D.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data provided by the Entrepreneurship Database Program at Emory University; supported by the Global Accelerator Learning Initiative based upon the application of co-author D. Fındık. Scholars who would like to have a similar access to data should send an application via https://www.galidata.org/data-request/ (accessed on 30 December 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Hypotheses to test mediation effect of equity funding and philanthropic support between independent and dependent variables.

Table A1.

Hypotheses to test mediation effect of equity funding and philanthropic support between independent and dependent variables.

| H3b. Equity funding raised by a sustainability startup before its application to accelerator mediates the relationship between the presence of team and being selected by accelerator. |

| H3c. Philanthropic support received by a sustainability startup before its application to accelerator mediates the relationship between the presence of team and being selected by accelerator. |

| H4b. Equity funding raised by a sustainability startup before its application to accelerator mediates the relationship between work experience diversity and being selected by accelerator |

| H4c. Philanthropic support received by a sustainability startup before its application to accelerator mediates the relationship between work experience diversity and being selected by accelerator. |

| H5b. Equity funding raised by a sustainability startup before its application to accelerator mediates the relationship between female entrepreneurship and being selected by an accelerator. |

| H5c. Philanthropic support received by a sustainability startup before its application to accelerator mediates the relationship between female entrepreneurship and being selected by an accelerator. |

| H6b. Equity investment received by a new venture before its application to accelerator mediates the relationship between a sustainability-startup team’s personal funding and being selected by an accelerator. |

| H6c. Philanthropic investment received by a new venture before its application to accelerator mediates the relationship between a sustainability-startup team’s personal funding and being selected by an accelerator. |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Impact area classification for sustainability startups.

Table A2.

Impact area classification for sustainability startups.

| Impact Objectives | Sustainability Impact |

|---|---|

| Access to clean water | social |

| Access to education | social |

| Access to energy | social |

| Access to financial services | social |

| Access to information | social |

| Affordable housing | social |

| Agriculture productivity | environmental |

| Biodiversity conservation | environmental |

| Capacity building | social |

| Community development | social |

| Conflict Resolution | social |

| Disease-specific prevention and mitigation | social |

| Employment generation | social |

| Energy and fuel efficiency | environmental |

| Equality and empowerment | social |

| Food security | social |

| Generate funds for charitable giving | social |

| Health improvement | social |

| Human rights protection or expansion | social |

| Income/productivity growth | social |

| Natural resources/biodiversity | environmental |

| Pollution prevention and waste management | environmental |

| Sustainable energy/fuel efficiency | environmental |

| Sustainable energy | environmental |

| Sustainable land use | environmental |

| Support for high-impact entrepreneurs | social |

| Water resources management | environmental |

| Support for women and girls | social |

Appendix C. Robustness

Table A3.

Test results of mediation analysis for social-sustainability startups.

Table A3.

Test results of mediation analysis for social-sustainability startups.

| Mediator: PEI | TEAM | FEMALE | AGE | EXPERIENCE | DIVERSITY | OWN INVESTMENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | |

| ACME | 0.001 (0.0001–0.003) | −0.003(−0.006–0.0006) | 0.001 (−0.0001–0.003) | 0.001 (0.0007–0.002) | 0.0009 (0.00002–0.002) | 0.0004 (0.0002–0.0007) |

| ADE | 0.062 (0.037–0.085) | 0.086 (0.042–0.132) | 0.011(−0.018–0.025) | −0.002(−0.012–0.008) | 0.007 (−0.012–0.026) | 0.001 (−0.0002–0.003) |

| Mediator: PPS | TEAM | FEMALE | AGE | EXPERIENCE | DIVERSITY | OWN INVESTMENT |

| (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | |

| ACME | 0.002 (0.0007–0.004) | −0.0006(-0.003–0.001) | −0.003(−0.007–0.001) | −0.0001(−0.0007–0.0003) | 0.001 (0.0001–0.002) | 0.0003 (0.0001–0.0005) |

| ADE | 0.062 (0.037–0.085) | 0.083 (0.040–0.12) | 0.016 (−0.012–0.02) | −0.0003(−0.010–0.010) | 0.006(−0.012–0.026) | 0.001 (−0.0001–0.003) |

Table A4.

Test results of mediation analysis for environmental-sustainability startups.

Table A4.

Test results of mediation analysis for environmental-sustainability startups.

| Mediator: PEI | TEAM | FEMALE | AGE | EXPERIENCE | DIVERSITY | OWN INVESTMENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | |

| ACME | 0.0009 (0.001–0.003) | −0.003 (−0.009–0.0006) | 0.003 (−0.000–0.007) | 0.001 (−0.0001–0.002) | −0.000 (−0.0011–0.001)) | 0.0003 (0.0001–0.0006) |

| ADE | 0.059 (0.015–0.099) | 0.076 (−0.007–0.17) | −0.04 (−0.12–0.02) | 0.01 (−0.004–0.02) | 0.03 (−0.001–0.06) | 0.002 (−0.0001–0.004) |

| Mediator: PPS | TEAM | FEMALE | AGE | EXPERIENCE | DIVERSITY | OWN INVESTMENT |

| (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | (95% conf. interval) | |

| ACME | 0.0005 (0.002–0.003) | −0.003(−0.009–0.002) | −0.006 (−0.013–0.0009) | 0.0001 (−0.0008–0.001) | 0.0001 (−0.002–0.002) | 0.0004 (0.0002–0.0008) |

| ADE | 0.059 (0.016–0.10) | 0.07 (−0.008–0.17) | −0.03 (−0.11–0.02) | 0.01 (−0.003–0.03) | 0.03 (−0.009–0.026) | 0.002 (−0.001–0.004) |

References

- Bergmann, T.; Utikal, H. How to Support Start-Ups in Developing a Sustainable Business Model: The Case of an European Social Impact Accelerator. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Fehder, D.C.; Hochberg, Y.V.; Murray, F. The Design of Startup Accelerators. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1781–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Kher, R.; Newbert, S.L. What signals matter for social startups? It depends: The influence of gender role congruity on social impact accelerator selection decisions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 105932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butz, H.; Mrozewski, M.J. The Selection Process and Criteria of Impact Accelerators. An Exploratory Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyhan, B.; Akçomak, S.; Cetindamar, D. The startup selection process in accelerators: Qualitative evidence from Turkey. Entrep. Res. J. 2021, 000010151520210122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño-Garrido, T.M.; de Lema, D.G.P.; Duréndez, A. Assessment criteria for seed accelerators in entrepreneurial project selections. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, B.; Luo, J. How Do Accelerators Select Startups? Shifting Decision Criteria across Stages. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2018, 65, 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, G.H.; Madill, J.; Riding, A.R. Informal investment in Canada: Financing small business growth. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2003, 16, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.; Stork, M. What do investors look for in a business plan? A comparison of the investment criteria of bankers, venture capitalists and business angels. Int. Small Bus. J. 2004, 22, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, N.; Gruber, M.; Harhoff, D.; Henkel, J. Venture capitalists’ evaluations of start-up teams: Trade-offs, knock-out criteria, and the impact of VC experience. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2008, 32, 459–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foo, M.-D. Member experience, use of external assistance and evaluation of business ideas. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2010, 48, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbers, J.J.; Winjberg, N.M. Nascent ventures competing for start-up capital: Matching reputations and investors. J. Bus. Ventur. 2012, 27, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plummer, L.A.; Allison, T.H.; Connelly, B.L. Better together? Signaling interactions in new venture pursuit of initial external capital. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1585–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.K.; Daneke, G.A.; Lenox, M.J. Sustainable development and entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halberstadt, J.; Schank, C.; Euler, M.; Harms, R. Learning Sustainability Entrepreneurship by Doing: Providing a Lecturer-Oriented Service Learning Framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S. A Framework for Ecopreneurship: Leading Bioneers and Environmental Managers to Ecopreneurship. Greener Manag. Int. 2002, 38, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, H.; Shepherd, D.A. Recognizing opportunities for sustainable development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Massa, L. The business model: Recent developments and future research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1019–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, F.G.; Garrido, M.A.V. Can profit and sustainability goals co-exist? New business models for hybrid firms. J. Bus. Strategy 2017, 38, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.; Post, J.E. Business models for people, planet (& profits): Exploring the phenomena of social business, a market-based approach to social value creation. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 715–737. [Google Scholar]

- Battilana, J.; Dorado, S. Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gupta, S.; Beninger, S.; Ganesh, J. A hybrid approach to innovation by social enterprises: Lessons from Africa. Soc. Enterp. J. 2015, 11, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala-Jaaski, S.; Puumalainen, K. Sharing a passion for the mission? Ange investing in social enterprises. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2021, 13, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, S.A.; Chen, L.W.; Roberts, P.W. Are we accelerating equity investment into impact-oriented ventures? World Dev. 2020, 131, 104952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yua, S. How do accelerators impact the performance of high-technology ventures? Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 530–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubitta, P.; Tognazza, A.; Destro, F. Signaling in academic ventures: The role of technology transfer offices and university funds. J. Technol. Transf. 2016, 41, 368–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, M.; Marlow, S. Sense and sensibility: The role of business incubator client advisors in assisting high-technology entrepreneurs to make sense of investment readiness status. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2011, 23, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, S.A.; Park, J. How Social Ventures Grow: Understanding the Role of Philanthropic Grants in Scaling Social Entrepreneurship. Bus. Soc. 2022, 61, 3–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Fremeth, A.; Marcus, A. Signaling by early stage startups: US government research grants and venture capital funding. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crişan, E.L.; Salanta, I.I.; Beleiu, I.N.; Bordean, O.N.; Bunduchi, R. A systematic literature review on accelerators. J. Technol. Transf. 2021, 46, 62–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, R.K.; Clausen, T.H. Scale Quickly or Fail Fast: An Inductive Study of Acceleration. Technovation 2020, 98, 102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stayton, J.; Mangematin, V. Seed Accelerators and the Speed of New Venture Creation. J. Technol. Transf. 2019, 44, 1163–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, C.; Clarysse, B.; Wright, M.; van Hove, J. Understanding a new generation incubation model: The accelerator. Technovation 2016, 50–51, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.G.; Hochberg, Y.V. Accelerating Start-Ups: The Seed Accelerator Phenomenon. 2014. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2418000 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Jashi, A.; Roh, H. The role of context in work team diversity research: A meta-analytic review. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 599–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amabile, T.M. How to kill creativity. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, I.; Woolley, A.W. Team creativity, cognition, and cognitive style diversity. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 1586–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astebro, T.; Serrano, C.J. Business partners: Complementary assets, financing, and invention commercialization. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2015, 24, 228–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucbasaran, D.; Lockett, A.; Wright, M. Entrepreneurial founder teams: Factors associated with member entry and exit. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanjer, A.; Witteloostuijn, A. The entrepreneur’s experiential diversity and entrepreneurial performance. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lazear, E.P. Entrepreneurship. J. Labor Econ. 2005, 23, 649–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J. Are nascent entrepreneurs ‘Jacks-of-all-trades’? A test of Lazear’s theory of entrepreneurship with German data. Appl. Econ. 2006, 38, 2415–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tegtmeier, S.; Kurczewska, A.; Halberstadt, J. Are women graduates jacquelines-of-all-trades? Challenging Lazear’s view on entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 47, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balachandra, L.; Briggs, T.; Eddleston, K.; Brush, C. Don’t Pitch Like a Girl! How Gender Stereotypes Influence Investor Decisions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 116–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, L.F.; Donnelly, R.; Manolova, T.; Brush, C.G. Gender stereotypes in the angel investment process. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2018, 10, 134–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poczter, S.; Shapsis, M. Gender disparity in angel financing. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 51, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmström, M.; Johansson, J.; Wincent, J. Gender stereotypes and venture support decisions: How governmental venture capitalists socially construct entrepreneurs’ potential. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 833–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C.G.; Carter, N.M.; Gatewood, E.J.; Greene, P.G.; Hart, M. Venture capital access: Is gender an issue? In The Emergence of Entrepreneurship Policy: Governance, Start-Ups, and Growth in the US Knowledge Economy; Hard, D.M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, J.; Kacperczyk, A. Gender gap in entrepreneurship. Res. Pol. 2019, 48, 1666–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker-Blease, J.R.; Sohl, J.E. Do women-owned businesses have equal access to angel capital? J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Huang, L. Gender Bias, Social Impact Framing, and Evaluation of Entrepreneurial Ventures. Organ. Sci. 2018, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, S.; Lee, M.; Ramarajan, L.; Battilana, J. Blurring the Boundaries: The Interplay of Gender and Local Communities in the Commercialization of Social Ventures. Organ. Sci. 2017, 28, 819–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, X.P.; Yao, X.; Kotha, S. Entrepreneur passion and preparedness in business plan presentations: A persuasion analysis of venture capitalists’ funding decisions. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitteness, C.R.; Baucus, M.S.; Sudek, R. Horse vs. jockey? How stage of funding process and industry experience affect the evaluations of angel investors. Ventur. Cap. 2012, 14, 241–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.W.; Liu, G.; Toren, W.; Yusoff, W.T.W.; Mat, C.R.C. Social Entrepreneurial Passion and Social Innovation Performance. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2019, 48, 759–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cardon, M.S.; Wincent, J.; Drnoysek, M. The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elsbach, K.D.; Kramer, R.M. Assessing creativity in Hollywood pitch meetings: Evidence for a dual process model of creativity judgments. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 283–301. [Google Scholar]

- Busenitz, L.W.; Fiet, J.O.; Moesel, D.D. Signaling in venture capitalist-new venture team funding decisions: Does it indicate long-term venture outcomes? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frid, C.J.; Wyman, D.M.; Gartner, W.B. The influence of financial ‘skin in the game’ on new venture creation. Acad. Entrep. J. 2015, 21, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, M.; Minniti, M. The effect of aging on entrepreneurial behavior. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; Down, S.; Minniti, M. Aging and entrepreneurial preferences. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sull, D.N. Disciplined entrepreneurship. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2004, 46, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R.T.; Mason, C.M. Backing the horse or the jockey? Due diligence, agency costs, information and the evaluation of risk by business angel investors. Int. Rev. Entrep. 2017, 15, 269–290. [Google Scholar]