Abstract

For sustainable product development, activities related to the selection of raw materials, product design, manufacturing, packaging, and distribution must be considered in a way that respects environmental limits and implements alternatives to reduce the consumption of natural resources. Due to this context, companies have sought to create environmentally sustainable alternatives for products and processes, once exposed to government, market, and regulatory pressures. Given this scenario, the question of this study is presented: Is it possible to define a conceptual model from existing models in the literature that guides companies in their Integrated Product Development Process (IPDP) and is oriented by Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM)? To answer the research problem question, a preliminary model integrating the IPDP and GSCM themes was presented. The elaboration of the preliminary model was only possible from the systematic literature review and content analysis previously carried out and presented in the general data in this article. The general aim of the study is to present a preliminary model in which IPDP is oriented to GSCM. As specific objectives, this study intends to present models previously published that have some relation to the IPDP related to green design, green purchase, green manufacturing, green distribution, and reverse logistics, which are related to GSCM; in addition, it presents guidelines to integrate the stages of product development and GSCM to reduce the environmental impact. The contribution of the preliminary model for companies is to present criteria that reduce the environmental impact of products in different GSCM activities within the IPDP. The contribution of this study is to present an analysis of the existing models, which will be the basis for the development of a conceptual model.

1. Introduction

With the increasing world population, which was close to 8 billion people in 2021, compared to 7.6 billion in 2017, and with the prospect of 8.6 billion in 2030, there is consequently an increased demand for products by customers, thus requiring an accelerated process of industrialization. Thus, the initial symptoms of the depletion of natural resources, significant climate change, and waste generation in the form of waste and emission of gases into the atmosphere have intensified [1,2].

Industries have been challenged to innovate in time, given the reality of ever-shorter product lifecycles. Consequently, the product development activity in companies is also challenged to work to shorter deadlines, but in accordance with the increasing demands of society, companies, and the environment.

The relationship between product development and the issues related to sustainability and GSCM had the highest number of publications in the period from 2011 to 2018, thus evidencing the importance of addressing the topic in the last nine years [3,4,5].

Although there is an international standard that directs companies in the management of environmental aspects, the ISO 14001:2015 [6], as well as a large number of published studies on the topics IPDP and GSCM, more in-depth studies are needed on the subject that contribute to a demonstration of the relationship of IPDP and GSCM, for the purpose of the integration of the “operations factor” [5,7].

It is important to highlight that the term GSCM is based on three factors: (i) strategy (formulation, performance evaluation, cooperation and communication, barriers, and impulse); (ii) innovation (process, product, and market); and (iii) operations (green purchasing, green manufacturing, green distribution, reverse logistics, and waste management). This research focuses only on the “operations” factor, specifically the “Purchasing, manufacturing and distribution process” [7,8,9].

The objective of this study is to present a preliminary model that integrates the concepts of IPDP and GSCM from a theoretical discussion about the influence of the approach of the themes. As specific objectives, this study aims to present the models published so far that have some relation to the IPDP as it is related to the green design, green purchase, green manufacturing, green distribution, and reverse logistics themes related to GSCM and present guidelines for the integration of the stages of product development and GSCM in order to reduce the environmental impact.

The present paper comes from a systematic literature review and content analysis. Through the study, it was possible to analyse the main contributions so far published in the literature [2,3]; these will contribute to the presentation of the preliminary model present in the discussion session of this paper.

The existing literature brings important contributions to the area, relating the different “operation factors”, such as green design [10], green purchasing [11,12] and supplier selection [13,14,15], production [12,16], distribution [10,16], reverse logistics [12], and final destination [16]. The inclusion of these important studies is related to the need for an update and review of the important publications used so far in the systematic literature review and content analysis [2,3,4,17].

Although the “operation factors” are widely discussed in the literature, the need to treat them from a systemic view of the product development oriented to the GSCM was verified. Therefore, the aim is to answer the problem question: “From existing Product Development Process models in the literature, is it possible to define a conceptual model that guides companies in their IPDP with a focus on GSCM?”

2. Models, Frameworks, and Research That Relate IPDP and GSCM

The models to be presented in the sequence originate from the systematic and bibliometric review and content analysis. The studies are related to the IPDP and GSCM theme and contribute to the development of a preliminary model, according to the operational factors: green design, green purchasing, green manufacturing, green distribution, and reverse logistics.

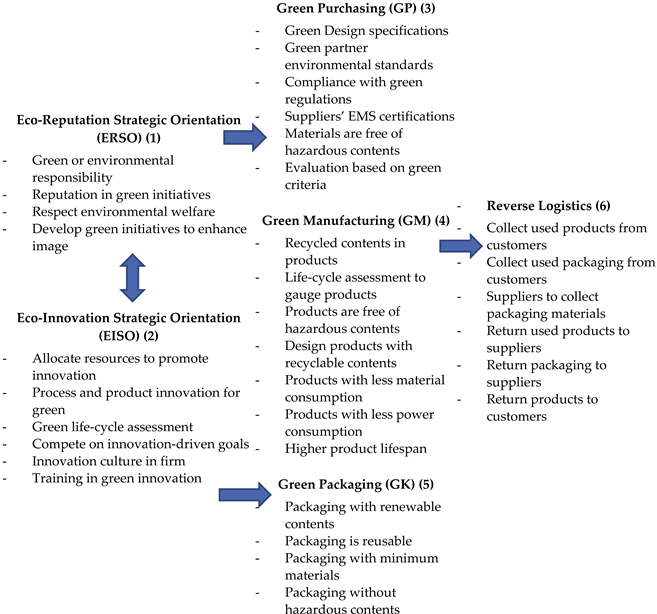

2.1. GSCM

GSCM is adopted by companies as a strategy that, together with suppliers, aims to achieve a certain level of environmental performance, thus stimulating the operational cooperation of all members of the supply chain. Although it has the same essence as a typical Supply Chain Management (SCM), GSCM aims at reducing to a minimum the environmental impact of a given product [7]. It comprises activities related to the supplier, manufacturing process, distribution, end-customer use, collection/disposition, recycling, and redistribution. In a systemic way, it also addresses the concepts of supply chain management, end of product lifecycle, green design, and supplier selection. This GSCM concept contributes to the inclusion of more activities related to the “operation factor” treated in this study [2,7,8,9,17].

The selection of suppliers should consider the environmental aspects as they are important competitive factors for large- and medium-sized companies. It is worth highlighting the importance of the long-term relationships with these suppliers as the suppliers’ environmental performance evaluation will be carried out frequently. The performance evaluation can be analysed from the perspective of different categories, such as environmental costs, management skills, green image, green design, environmental management system, and environmental skills. Still, to be highlighted are the important initiatives and study opportunities of the pollution prevention and control systems; the continuous improvement and innovation of the designs of products and the manufacturing processes; and the implementation of waste management systems, to establish future reuse, recycling, and disposal of materials [18].

GSCM is inserted into a competitive market environment; thus, the GSCM practices are influenced by this environment and include the practices of internal environmental management, green purchasing, eco-design, cooperation with customers, and reverse logistics. These practices impact on the manufacturing performance and marketing performance. The practices were analysed and composed into a hypothetical model, which showed, as a result, that green purchasing is the most effective practice among the five practices analysed (Table 1) [19].

Table 1.

Based on hypothetical model [19].

The hypothetical model presented includes an analysis of the competitive market environment, the internal environmental management, cooperation with customers, the manufacturing performance, and the marketing performance (Table 1), when compared to the GSCM process workflow activities. Such inclusion is important because competitive performance factors have a great relevance when analysing GSCM.

When sustainable aspects are thought of strategically, they enable the company to create a competitive advantage. Thus, GSCM can be a driver for a company’s business. Thus, as it can be a driver, when there is a lack of integration of the sustainable practices of the upstream supply chain partners (suppliers) and the downstream (customers), the effect can be to the contrary; that is, the result can be a reduction in profits [20]. Thus, specific criteria, such as environmental responsibility and social behaviour, need to be applied by all members of the supply chain to obtain greater and more lasting benefits [20]. GSCM, besides reducing environmental and social impacts, can also improve operational effectiveness in the following spheres [20]:

- i.

- Green design—product designs that aim to reduce environmental impact throughout the lifecycle and take this into consideration from the early stage of the new product development and production processes;

- ii.

- Green operations—related to the aspects that make the product green; that is, it covers operations such as remanufacturing, handling, reuse, logistics, and waste management after the product design phase;

- iii.

- Green manufacturing—reducing environmental impact by selecting recycled or reused products or products that have been reconditioned/remanufactured;

- iv.

- Green packaging—by using fewer materials, it is possible to obtain smaller, thinner, and lighter packages. The possibility of recycling the packaging must be considered, along with the smaller space occupation in storage and transport activities;

- v.

- Waste minimization—the reduction in production and operational waste;

- vi.

- Reverse logistics—this involves the processes of planning, development, and control of the flow of materials, products, and information from the place of origin to the place of consumption. Companies involved in the process must manage and recover waste by reintroducing it into the supply chain in such a way as to add value to the operation; in cases where reintroduction is not possible, adequate disposal must be provided.

The studies addressed in this research are related since the GSCM practices that are influenced by the competitive environment are understood [19] and complemented by the operational spheres and the inputs of the supply chain [20]. These elements form the factors that will be the parameters used in the operational spheres and mainly determine which inputs and influence these factors have on the GSCM.

When dealing with GSCM, the related activities [18,19,20] should be conducted thinking about the reduction in the environmental impacts. From the supplier selection activity to the reverse logistics process, what should be considered in the key development process are those aspects that are treated in a cyclical way, i.e., the reverse logistics, either post-sale (return of a product to the manufacturer) or post-consumption (return of a product at the end of its useful life), which may be an input of remanufactured or recycled raw materials that can be used in the production process.

2.2. Green Purchasing

After the selection of suppliers, the purchasing process begins. This is an activity that in a study developed in high technology industries was approached in a strategic way. The study relates the theme of green purchasing and the role of top management in the purchasing process, through the presentation of a theoretical conceptual model to analyse the process of the adoption of green purchasing by managers [11].

The study examines the impact of top management commitment to regulations, customer pressure, and the supplier adoption of the requirements on the adoption of green procurement by the company. Through this study, the determinants leading to green purchasing adoption are listed and include environmental collaboration with suppliers, top management commitment, regulatory pressure, environmental investment, and customer pressure, as well as analyses of how top management commitment affects green purchasing (Table 2) [11].

As observed in the results in Table 2, the “Logistics integration with suppliers” (hypothesis H1), the “Technological relationship with suppliers” (hypothesis H2), and the “Top management commitment” (hypothesis H3) have a positive and significant influence on the “Environmental collaboration with Suppliers”. In addition, the “Environmental Collaboration with Suppliers” and the “Top management commitment” also have a positive and significant influence on “Green Purchasing” (hypotheses H4 and H5), respectively.

From the evidence presented, it is insufficient to say that the regulatory pressures (hypothesis H6) and the environmental investment pressures (hypothesis H7) significantly influence Green Purchasing. In relation to the regulatory pressures, the hypothesis is considered consistent once the importance of these factors is already found in the literature. To also be considered is the indifference of some companies regarding the compliance with governmental legislation. Therefore, the pressure from customers (hypothesis H8) has a significant and positive influence on companies when related to green purchasing, driving the supply chain members to environmental initiatives. As limitations, the authors suggest applying this conceptual model in the industries of other sectors and in other countries, as it was applied only in the electronics industry in Taiwan. The authors also agree with the highlighting of the importance of the activities and decisions related to the purchasing process as it is directly linked to the activities of research and development (R&D), quality management, and sales [11].

Table 2.

Based on conceptual model [11].

Table 2.

Based on conceptual model [11].

| Environmental Collaboration with Suppliers | Logistical integration with suppliers | H1 |

| Technological integration with suppliers | H2 | |

| Top management commitment | H3 | |

| Green purchasing | H4 | |

| Green purchasing | Top management commitment | H5 |

| Regulatory Pressure | H6 | |

| Environmental investment pressure | H7 | |

| Customer pressure | H8 |

Another related study brings an analysis of suppliers according to environmental criteria. The study aims to identify suppliers that could meet the criteria defined by the purchasing company, according to an environmental cost ranking order (Table 3) [13]. The supplier selection process is made through environmental categories, such as environmental costs (pollutant effects), environmental costs (improvement), management competencies, “green” image, design for the environment, environmental management systems, and environmental competencies. The environmental categories are divided into Quantitative Environmental Criteria and Qualitative Environmental Criteria [13].

Table 3.

Based on framework for incorporating environmental criteria into the supplier selection process [13].

The environmental costs addressed in the study are:

- i.

- solid waste disposal cost—these are the treatment costs and transportation costs of the solid waste to be disposed;

- ii.

- cost of disposal of chemical waste—this is related to the cost of the treatment for disposal of toxic chemical materials, such as lead, which has a harmful effect on the body;

- iii.

- cost of treatment of air pollutants—this is the cost of treatment prior to the emission of gases produced (e.g., sulphur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide);

- iv.

- water treatment—this is the cost involved in the disposal of waste in water, such as for filtration and waste storage systems;

- v.

- energy consumption costs—these are the energy-related costs necessary to produce the product. The higher these costs are, the lower the supplier’s efficiency.

Besides the studied environmental costs, the criteria involved for the analysis of the environmental cost category to which they belong are also indicated. These categories are related to the improvements that can be made in the process [13]. Five criteria are described in this evaluation:

- i.

- costs for purchasing environmentally friendly material—these are the costs associated with purchasing environmental products instead of purchasing virgin material;

- ii.

- costs for purchasing new equipment—these are the costs associated with the purchase of new equipment that can lead to improvements in environmental performance;

- iii.

- product redesign costs—these are the costs to redesign a product so that it can, for example, disassemble easily or use less materials in its production;

- iv.

- staff training costs—these are the costs associated with training staff to improve their knowledge of environmental management and cleaner technology;

- v.

- recycling costs—these are the costs of recycling the product, which, when considering the amount of solid waste, can be eliminated or reduced.

In addition to the environmental costs and the respective criteria, the qualitative environmental categories were identified and weighted, i.e., the user needs to select the category he/she wants to evaluate and assign weightings to according to the selected categories and the importance of the analysis to be performed [13]. When performing a qualitative analysis of supplier quality in relation to environmental characteristics, the following qualitative aspects are considered, as listed below (Table 3) [13]:

- i.

- management decisions—this is the management support required to implement “green” programs and the level of environmental training provided to employees. Information exchange with government and other companies is also involved;

- ii.

- green image—this refers to the sharing of information with the market and stakeholders regarding the image of the company with the implementation of environmentally responsible programs and products;

- iii.

- environmental design (design for environment)—this is the verification of the supplier’s capacity to develop a product with an environmental design, e.g., detachable products;

- iv.

- environmental management systems—this concerns the supplier’s environmental policies, as well as the implementation and certification of ISO 14001;

- v.

- environmental competences—this is the supplier’s capacity to reduce the effects of pollution and to implement clean technology and the use of environmentally correct materials.

A model derived from an adaptation of the framework for the incorporation of environmental criteria in the supplier selection process (Table 3) [13] was applied to companies in Brazil. The study highlights the relationship with suppliers, focusing on analysing whether Brazilian companies are considering environmental aspects in the supplier selection process. An interview was conducted in five distinct sectors, and the existence or not of the relationship between maturity in environmental management and the inclusion of the environmental criteria for supplier selection was also analysed [14].

To adapt the framework (Table 4), the authors listed quantitative and qualitative environmental criteria for the selection of suppliers, criteria that were the basis for the questionnaire applied to the companies. Although the framework was not developed by the authors, it constitutes an important bibliographic reference [14].

Table 4.

Based on framework to incorporate environmental criteria in the supplier selection process [14].

As limitations, the authors highlight that the results of the case study cannot be considered a reality in all Brazilian companies. Thus, they suggest that future research be conducted related to environmental management and the inclusion of criteria for supplier selection; the environmental performance of products and the environmental performance of suppliers; the availability of environmental information on the suppliers and the selection of suppliers with a high environmental performance.

Although the contribution of the quantitative aspects addressed by the frameworks (Table 3) is acknowledged (Table 4), emphasis was given to the qualitative aspects as these are aligned with the processes to be presented in the model at the end of this article [13,14].

The supplier selection based on quantitative and qualitative criteria was also studied through the framework of supplier selection based on hazardous substance management (HSM), using the analytic network process (ANP) methodology (Table 5). The framework has been tested in electronic companies [15].

Table 5.

Based on framework for selecting suppliers based on environmental criteria [15].

The supplier selection is based on dimensions such as procurement management, R&D management, process management, incoming quality control, and the management system. Each dimension has its criteria and different suppliers as alternatives (Table 5) [15].

Through the ANP, the authors were able to verify the quantitative and qualitative criteria that can contribute to the decision process. With the choice in the supplier selection, there are also interdependent relationships that may interfere in the supplier evaluation and selection process. This enables companies to use the framework if they need to select HSM suppliers according to the GSCM practices. The model is relevant as it features supplier selection with an emphasis on HSM. Regarding the method used, by using the ANP it is possible to collect qualitative and quantitative data [15].

The GSCM theme presented first brings a study about the decision-making process that impacts purchasing, a process that is the responsibility of top management, which can opt for the adoption of green purchasing [11]. Once the top management is involved in the purchasing process, the next step is that the suppliers should be analysed according to quantitative and qualitative environmental criteria [13,14]. Other criteria can also be adopted for the selection of suppliers, based on the objectives that the company wants to achieve. An example is the selection of suppliers based on the management of hazardous substances [15].

2.3. Green Production, Green Distribution, and Reverse Logistics

For the continuity of the GSCM activities, besides the green purchasing processes, the studies that address green production, green distribution, and reverse logistics will be related.

The strategies for the reduction in the environmental impact in the phases of a product’s lifecycle can be related to activities such as green purchasing, sustainable processes in distribution, and reverse logistics (Table 6) [16].

Table 6.

Based on environmental impact in life cycle phases [16].

In this research, the environmental impact was analysed from the perspective of the ecological and carbon footprint. The ecological footprint refers to solid or liquid waste discarded directly or indirectly into the environment; this disposal can occur from the raw material phase, production, distribution, and use and disposal. The ecological footprint mainly measures the effects of the supply chain on the environment. Therefore, the carbon footprint refers to the greenhouse gas emitted directly or indirectly into the atmosphere and also covers the raw material, production, distribution, use, and disposal phases (Table 6) [16].

In production, the environmental challenges were measured by the presence of toxic substances such as arsenic, brominated flame retardants (BFRs), mercury, phthalates (additive responsible for plastic malleability), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Another environmental challenge addressed is in relation to the amount of carbon emissions, evidencing the need for the entire supply chain to reduce both types of environmental impact. In the study, some initiatives were highlighted at the level of production, distribution, product use, and product disposal (Table 7) [16].

Table 7.

Based on environmental impact reduction strategies in life cycle phases [16].

As initiatives at the production level to be executed by companies in search of the reduction in the environmental impact, the following can be highlighted:

- i.

- management decisions—these are in relation to the accuracy of demand forecasting. By improving the accuracy of demand forecasting, it is possible to reduce the existing mismatch between supply and demand and reduce the number of products in stock that eventually were not sold. Demand uncertainty generates inefficiency in production as raw materials had to be used, and toxic substances were emitted, in the production of a product that was not sold (Table 7—detail 1);

- ii.

- carbon footprint reduction strategies—both the industry and the supply chain in which this industry is inserted must understand the emissions measures. Regarding carbon emission, it can be traded as carbon credit among companies of the same supply chain (Table 7—detail 2);

- iii.

- toxic substance removal—to design more ecological products, the environmental impact that the used materials have must be considered; so, the company must seek alternatives for the elimination of toxic substances in a product (Table 7—detail 3).

In the distribution phase, most of the environmental impact is related to carbon emission, which can be minimized through the efficiency of the fuel used, the size of the load transported, and the distances travelled [16]. For this, we highlight the strategies for reducing environmental impact in the distribution of products, such as:

- i.

- load-size improvements—these improvements are associated with the packaging design process so as to reduce the waste coming from the product packaging and improve the cargo packaging in the vehicle because when the number of products to be transported in a load is increased, it is possible to increase the utilization capacity of the vehicle (Table 7—detail 4);

- ii.

- joint distribution—the joint distribution shows that different companies could use the same transport and storage, with the possibility of return freight with goods, thus enabling a cost reduction and a reduction in carbon dioxide emissions (Table 7—detail 5);

- iii.

- coordination with logistics operators—logistics operators are able to use larger vehicles because they gather consignments from several companies. Thus, by working with third-party logistics operators, manufacturers may meet smaller orders to be consolidated with other manufacturers. Thus, they contribute to the reduction in the pollutant emissions associated with the transport activity (Table 7—detail 6);

- iv.

- cross-docking—manufacturers send full loads of products to cross-docking centres; these products are consolidated into loads which are packed in smaller vehicles and then transported to retailers. There is no stock at the cross-docking centre, which eliminates stock-holding costs and enables the reduction in carbon emissions (Table 7—detail 7).

In relation to product use, the study emphasizes the use of energy efficiency, which consists of strategies that encourage the consumer to reduce the time of use of a product, through the purchase of another product with better energy efficiency (Table 7—detail 8). The disposal of the product may have its environmental impact reduced, provided that measures are adopted, such as:

- i.

- ecological design—in the product design and manufacturing phases, the cradle-to-cradle (C2C) design must be considered; it aims to create and recycle unlimitedly. Thus, the whole productive process is mapped and modelled, enabling manufacturers to analyse residues and respective discards, as well as to identify suppliers that develop components and modules that may be reused and/or recycled (Table 7—detail 9);

- ii.

- recycling networks—manufacturers may voluntarily contribute to the construction of reverse networks that aim at recycling and remanufacturing, even if this has an economic purpose. Opportunity costs must be analysed in relation to recycling scales in the search for the alignment of environmental and economic performance (Table 7—detail 10).

A contribution of the article is to highlight the relationship of strategies for the reduction in environmental impact at the production, distribution, use, and disposal levels. At the production level, the strategies to be adopted are improvements in the accuracy of demand forecasting, carbon footprint reduction strategies, and the removal of toxic substances. At the distribution level, the strategies are improvements in cargo size, joint distribution, coordination with logistics operators, and cross-docking. The strategy at the use level is related to energy efficiency. Then, at the disposal level, there are the eco-design and the recycling networks [16].

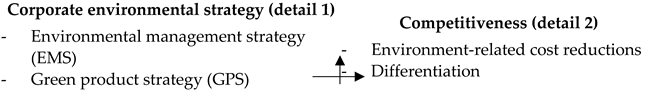

The concepts of green purchasing, green design, distribution, and sustainable processes in product distribution have been identified and presented in a conceptual model that provides a theoretical basis on corporate environmental strategy, competitiveness, and environmental collaboration in supply chains, including environmental management strategy, green product strategies, cost reduction related to environmental practices, differentiation, environmental collaboration among suppliers, and environmental collaboration with customers (Table 8) [10].

Table 8.

Based on conceptual model [10].

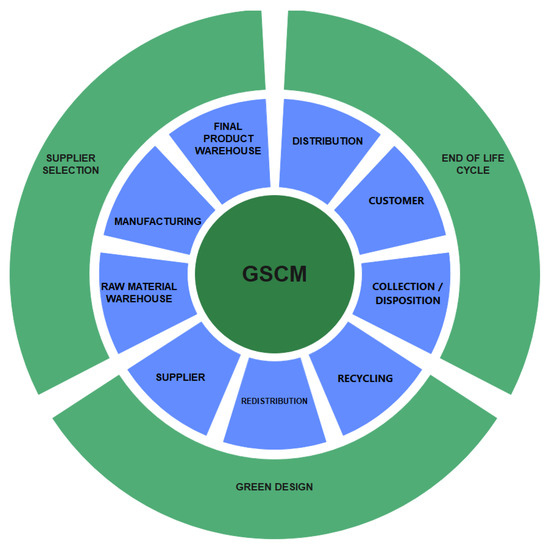

The corporate environmental strategy is related to the range of organizational actions that aim to reduce the impact on the environment. The company becomes committed and mobilises efforts towards green products, processes, and management systems. In the conceptual model, the corporate environmental strategy was subdivided into environmental management strategy (EMS) and green product strategy (GPS) (Table 8—detail 1).

The corporate environmental strategies were analysed in order to understand the interactive effects with the supply chain. The environmental management strategy seeks to identify a company’s commitment to internal operations and management systems and to understand how these factors can affect the company’s performance. Green product strategy then evaluates the search for economic results by mobilising the environmental efforts. Both approaches can be linked to the products, production, and management mechanisms through an environmental perspective and can also represent the introduction of sustainability issues in the corporate environmental strategy.

In relation to competitiveness, this is associated with the potential of a corporate environmental strategy to contribute to improved long-term profitability because sustainability has transformed the competitive landscape, motivating companies to go green. On the other hand, there may be the opposite effect; executives may choose to meet the lowest environmental standards for as long as possible and interpret regulatory forces as threats rather than opportunities (Table 8—detail 2). Companies that choose to adopt environmentally friendly practices formulate strategic objectives to obtain a competitive advantage, resulting in an improved corporate image, cost reduction, and market differentiation competitors.

In relation to competitiveness, environmental cost reduction and differentiation were analysed. When addressing environment-related costs, managers must transform environmental paradigms into profits by encouraging companies to develop and implement green practices. Consequently, the competitive effects of the adopted environmental strategy can help managers to increasingly seek greater responsibility for the environment through indicators that can assist in understanding the relationship between the companies’ environment-related costs versus the benefits that these can bring to the company in relation to profit margins, markets, and products.

The environmental collaboration in supply chains (ECSC) plays an important role when companies choose to adopt voluntary environmental practices. Companies can identify competitive strengths when approaching green initiatives in a supply chain through eco-design, lean production, environmental strategies, and the search for potential opportunities. In this sense, opportunities exist for an individual company to become a highly efficient and sustainable company through environmentally specific supply chain cooperation. Environmental collaboration in supply chains is possible through environmental collaboration with suppliers (ECS) and environmental collaboration with customers (ECC) (Table 8—detail 3).

The environmental collaboration among suppliers is related to the direct involvement of a company with its suppliers, covering the phases of planning and the implementation of sustainable practices that respect the environment and that are aligned with the suppliers’ environmental management system, product design, process, distribution, and pollution prevention (Table 8—detail 3).

In relation to environmental collaboration with customers, this is related to the involvement of a company directly with customers in search of joint development of solutions for environmental issues. For this to occur, targets are set in relation to environmental management, the operational processes, and the technologies related to eco-design, clean production, green packaging, distribution, reverse logistics, and recycling programs (Table 8—detail 3).

The relevance of the study stands out as, based on a questionnaire, regression analysis was used to understand how corporate environmental strategies, environmental management strategies and green product strategy impact corporate competitiveness. As limitations, we highlight that the study focuses on a limited number of green initiatives and does not consider the difference between short- and long-term effects.

Management actions can contribute to sustainable initiatives in the supply chain. Thus, the importance of compliance with environmental requirements is highlighted as a key criterion for products and production in companies that seek to ensure economic sustainability, competitiveness, and profitability. The implementation of sustainable initiatives in the supply chain can lead to the creation of value and competitive advantage through strategic orientation, sustainable initiatives, and results in a supply chain, as well as the concepts of green design, green purchasing, cleaner production and reverse logistics (Table 9) [12].

Table 9.

Based on managerial implications [12].

The strategic orientations were subdivided into Eco-Reputation Strategic Orientation (ERSO) and Eco-Innovation Strategic Orientation (EISO). ERSO is related to the adoption of sustainable business practices in response to stakeholder expectations, in this case customers. The eco-reputation practices analysed were environmental or green responsibility, reputation/involvement in green initiatives, promotion of green initiatives through company policy, respect for the environment, and development of green initiatives to improve the image (Table 9—detail 1).

EISO is related to the corporate capacity to integrate, establish, and reconfigure external and internal resources that do not harm the environment. This context makes companies develop new values by developing or improving products, services, and processes that are ecologically efficient and effective. The analysed eco-innovation practices were the allocation of resources to promote innovation, innovation of processes and products aimed at green initiatives, evaluation of the lifecycle of a green product, competition based on innovative goals, innovation culture in the company, and training in green innovation (Table 9—detail 2).

The initiatives of a sustainable supply chain were classified into green purchasing (GP), green manufacturing (GM), and green packaging (GP). By adopting green purchasing criteria, one should reflect on efforts to reduce, reuse, and recycle materials, which will have a significant impact on the environmentally sustainable supply chain. Green purchasing was analysed through the criteria of green design specifications, the environmental standards of green partners, compliance with regulations focused on green and environmental aspects, certifications of suppliers’ environmental management systems, materials free of hazardous content, and supplier evaluation based on green criteria (Table 9—detail 3).

Green manufacturing involves the environmentally responsible production of a product, aiming at minimising negative environmental impacts throughout its lifecycle. In this manufacturing context, it is important to prioritise the recycling and reuse of materials, minimising the environmental impacts of manufacturing processes, minimising waste, and reducing environmental pollution. Cleaner production can enable a company to reduce raw material costs and seek to achieve production efficiency as well as have a positive impact on the corporate image. The criteria for the cleaner production analysis are the recycling of components used in the products, the product lifecycle assessment, the making of products that do not contain hazardous substances, and the designing of products with recyclable components, products with reduced material consumption, and products with reduced energy consumption and longer product life (Table 9—detail 4).

With green packaging, the minimisation of environmental impacts is sought as packaging contributes directly to the supply chain through the efficient distribution of the products. Factors such as size, shape, and materials have different impacts when it comes to environmental impacts as they are directly related to the distribution process, efficiency in load assembly, handling, and use of space. When dealing with green packaging, the following should be considered: cost (materials and shipping), performance (adequate protection of the product), convenience (ease of use), compliance (legal requirements), and environmental impact. For green packaging analysis, packaging with renewable components, packaging reuse, packaging with a minimum number of materials, and packaging free of hazardous substances were analysed (Table 9—detail 5).

Manufacturing industries have become more and more responsible for collecting, disassembling, and updating the parts of products and materials used in packaging. In this context, reverse logistics plays an important role as it enables products at the end of their lifecycle to undergo further transformation, instead of being dumped in landfills. For the analysis of reverse logistics, one highlights the collection of used products by customers, the collection of packaging from customers, the suppliers for the collection of products, the return of used products to suppliers, the return of packaging to suppliers, and the return of products by customers (Table 9—detail 6).

The drivers presented can contribute to sustainable initiatives in the supply chains, highlighting the benefits when addressing the reverse logistics theme. Environmental requirements are key criteria for products and production in companies that seek to ensure economic sustainability, competitiveness, and profitability. The study presents evidence that the implementation of sustainable initiatives in the supply chain can lead to the creation of value and competitive advantage from the adoption of reverse logistics [12].

There are different ways to the recover costs and revenues related to a developed product, which depend on product characteristics, such as price, transport costs, product shelf life and market demand patterns. Reverse logistics may enable new businesses in ways such as (i) selling as a new product; (ii) repairing or repackaging and reselling as a new product; (iii) repairing or repackaging and reselling as a used product; (iv) reselling at a lower price to a used goods shop; and (v) reselling by the kilo to a used goods shop [21].

In presenting a conceptual model of the decision to recover a product in a supply chain by means of reverse logistics, the five strategies most used by companies were analysed [21]. These are:

- i.

- destruction—products are destroyed when they cannot be sold/used by the customer, and return is not feasible (for reasons of high transportation cost or a small quantity of products);

- ii.

- recycling—the return of the product for rework or disposal is usually mandatory for legal reasons. Recycling is chosen when a component can be used in another product or as a sub-assembly item;

- iii.

- refurbishment—this is related to the improvement or effort employed to improve the product;

- iv.

- remanufacturing—this differs from refurbishment because there is a degree of improvement; that is, the product is exchanged and the parts are replaced and then sold;

- v.

- repackaging of returned products—the product is repackaged for reshipping and resale but is not reworked or remanufactured.

Although reverse logistics strategies contribute to the present study, this has the limitation of being a study only of reverse logistics and not the impacts within a supply chain because the research aims to verify the relationship between reverse logistics strategies and company performance in terms of economic performance, operational responsiveness, and service quality [21].

In approaching the GSCM theme, this has some critical success factors for implementation with a focus on environmental sustainability and green practices. Thus, based on the implemented criteria, the results are analysed from the perspective of performance analysis obtained through such implementation [22]. The critical success factors for implementation of GSCM for sustainability were classified into six variables and applied to the Indian automobile industry. These are:

- i.

- internal environment management—this is related to the support from managers to implement GSCM practices;

- ii.

- customer management—in developing countries, customers have been exerting strong pressure for the implementation of green practices in supply chains, thus impacting market competitiveness. Thus, customer collaboration becomes very important for GSCM practices;

- iii.

- regulations—the regulatory agencies have formulated strict environmental regulations to minimize impacts to the environment; on the other hand, companies are required to reduce impacts in supply chains to make them environmentally sustainable. Companies need to maintain their level of competitiveness in the market but at the same time meet compliance standards in relation to regulations.

- iv.

- supplier management—the best GSCM practices can only be implemented from partnerships with suppliers through the interaction process between supplier and client, the development of technologies that aim at reducing environmental impact, and the adoption of innovative practices that may contribute to improvements in environmental performance but that enable the achievement of production, quality, and economic goals;

- v.

- social—with the growing awareness and concern of people with environmental issues, organizations need to be transparent when disclosing information about the impacts of operations on society;

- vi.

- competitiveness—the competitiveness factor may improve GSCM practices as it is treated as a voluntary factor. As it is voluntary, it may present better results when compared to governmental regulations, with which compliance is mandatory on the part of companies. Highlighted in the study are the environmental practices for sustainability, which were related in six practices [22].

With regard to the environmental practices for sustainability, we have:

- i.

- green design—when thinking of a product project, from raw materials to reverse logistics, it is possible to reduce the environmental impacts of products and processes through green design practices;

- ii.

- green purchasing—purchasing professionals must reconsider their purchasing strategies due to the growing concern for environmental issues. Thus, products are chosen that can be recyclable and reusable and do not use hazardous materials;

- iii.

- cleaner production—the application of the practices aims at reducing negative impacts on the environment, while ensuring process efficiency;

- iv.

- green management—the implementation of better management practices may lead to the improvement of the corporate image, improvement in the conformity standards according to environmental criteria, efficiency increase, fulfilment of social commitment, cost reduction, and emissions reduction. To comply with the mentioned factors, the companies, besides implementing green management practices, may monitor the information with the purpose of improving the environmental and business performance;

- v.

- green marketing—the practices to promote or advertise a product that meets environmentally correct criteria. The objective of green marketing is to meet customer needs through products that have the least negative impact on the environment. Green marketing practices enable the improvement of the corporate image, of the product image, and of the corporate reputation;

- vi.

- green logistics—the integration of activities related to the transportation of products along the supply chain, also including reverse logistics activities. An efficient transportation and distribution system may contribute to the reduction in logistic costs and at the same time meet the client’s needs within the required timeframe.

Based on the six critical success factors for implementing GSCM and the six environmental practices for sustainability, the results related to performance evaluation are expected. For this, the four categories of performance expected from the implementation of GSCM practices in the Indian automobile industry were established in relation to the expected outcomes [22].

As the results of the six critical success factors for GSCM implementation and the six environmental practices for sustainability, the four performance categories expected from the implementation of GSCM practices in the Indian automobile industry were classified [22]. The expected results are:

- i.

- economic performance results—cost reduction is considered an important factor for companies when engaging in sustainable initiatives. As such, the adoption of GSCM initiatives can help reduce raw material and packaging costs due to the use of recycled/reused materials;

- ii.

- social performance results—these indicate the improvement and maintenance of people’s quality-of-life standards, preferably without causing negative impacts to the environment and overexploitation of natural resources;

- iii.

- environmental performance results—these are initiatives related to suppliers and the environmental management system in the manufacturing processes, which may contribute to the supply chain becoming more sustainable;

- iv.

- operational performance results—GSCM initiatives may contribute to the improvement in the quality of products and processes and to improvement in the distribution of the products as well as to the principles at the operational level that contribute so that the supply chain becomes environmentally sustainable.

The drivers presented as managerial implications (Table 9) [12] are complemented through the presentations of the present variables [22]. A convergence is identified regarding green purchasing and cleaner production, but activities related to green packaging, green management, green marketing, green logistics, and reverse logistics are important activities to be studied, and both studies, when analysed together, contribute to the evolution of the presentation of the model.

The variables, models, and frameworks found for the development of the present thesis are references that have greater adherence to the study and enable possible adaptations for a product development perspective [10,12,16,21,22]. Through the studied models, the elaboration of a preliminary model of product development was possible that integrates the green design, green purchase, cleaner production, and sustainable processes in the distribution of products and reverse logistics.

3. Materials and Methods

To search for models so far already published in the literature on the influence of an IPDP and GSCM approach, a search was conducted in the Periodical Portal of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher-Level Personnel (CAPES), with keywords that addressed the topic.

The CAPES portal is a Brazilian database subordinated to the Ministry of Education, which offers access to full texts available in over 45,000 international and national periodicals and various databases. The database contains references and abstracts of academic and scientific papers, technical standards, patents, theses, and dissertations, among other types of material, covering all areas of knowledge. It also includes a selection of important sources of scientific and technological information freely available on the web [23].

In the first instance, an exploratory view of the literature on the concepts that would be addressed was sought, such as sustainable supply chain, green supply chain, product development process, method, model, and industries. The purpose of this exploratory vision was to obtain an initial perception of the research field. Next, trial and error was conducted in search of keyword combinations that might bring results.

After a few attempts with distinct keyword combinations, the combination of words that presented the highest search effectiveness was: (“SUSTAIN SUPPLY CHAIN IMPLEMENT” OR “GREEN SUPPLY CHAIN IMPLEMENT”) AND (“PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT PROCESS” OR “PDP”) AND (“MODEL” OR “METHOD” OR “AP-PROACH” OR “SYSTEMAT”) AND (“INDUSTR” OR “ENTERPRISE”).

From the keywords, it was necessary to refine the search on the portal; for this, some criteria were selected in the database, such as type of resources—article, language—English, and peer-reviewed journals. Found as a result of the search on the Portal de Periódicos da Capes was a total of 9430 articles. Of the articles found, it was verified that some journals were not related to the research theme, these being journals found in the areas of Psychology, Health, Medicine, Sociology, and Social Policies. Thus, these periodicals which approached these themes were considered as exclusion factors.

For a new classification of the articles, new inclusion and exclusion criteria were elaborated, which had the objective of verifying the relationship between the articles and the research theme. The inclusion criteria were articles that dealt with product development, suppliers, production, distribution, green products, and green supply chain management. As exclusion criteria, there were articles that had subjects related to finance, e-commerce, radio frequency identification (RFID), social sustainability, lean manufacturing, and agriculture.

In addition to the review regarding the subject, the articles were classified according to the quality of the journals in which they were published. Only journals with high impact factor (SJR > 1; Q1) were selected, resulting in 744 articles. Next, the journals where these articles had been published were analysed in order to understand which were the main journals that addressed the topic.

From the inclusion and exclusion criteria, there began the reading of all the titles and abstracts of the articles. This time, the inclusion and exclusion factors of the studies were considered that were related to the GSCM and IPDP, resulting in 335 articles that met such criteria.

After the analysis of title, the abstract, and the introduction, for the content analysis the articles were classified according to the Likert scale: very important (3), important (2) and only reference (1), resulting in the selection of very important articles that were related to the research theme. Thirty-three articles were classified as very important [7,10,22,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. From the 33 articles, the content analysis was started, in which it was necessary to read the articles completely, checking which ones addressed in depth the topic of product development, supply chain, green supply chain, suppliers, production and distribution. In the content analysis, the contributions, limitations, and the relationship of IPDP and GSCM were analysed [3].

To analyse publications from the second semester of 2019, the present article brings relevant studies that will be presented in session three and that contributed to the elaboration of the preliminary model. It is noteworthy that the systematic literature review, the content analysis, and the preparation of the preliminary model were carried out by the researchers involved in this study. They met frequently for the analysis and alignment of the concepts, starting from a deductive method, where the starting point of the research was the IPDP and GSCM, and in the sequence, the activities and practices that were related to the concept were found. After the discussions between the authors, it was possible to have a convergence of concepts that resulted in the presentation of this article.

4. Discussion

This item presents a broad discussion on the activities and environments that are conceptually involved in Green Supply Chain Management. With this, it was possible to propose a preliminary model of IPDP (Integrated Product Development Process) oriented to Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM). This discussion is divided into three topics, which are: (i) activities and environments inside and outside the GSCM; (ii) the preliminary model of the integrated product development process oriented by GSCM; and (iii) the existing relationships between the macrophases and the phases of the IPDP and GSCM.

4.1. GSCM Activities and Internal and External Environments

After the presentation of some studies that are related to the present research, the gaps related to the integration of the activities of green design, green purchasing, green manufacturing, green distribution, and reverse logistics with the IPDP are observed. These subjects are presented relating some areas of knowledge but with gaps in the integration.

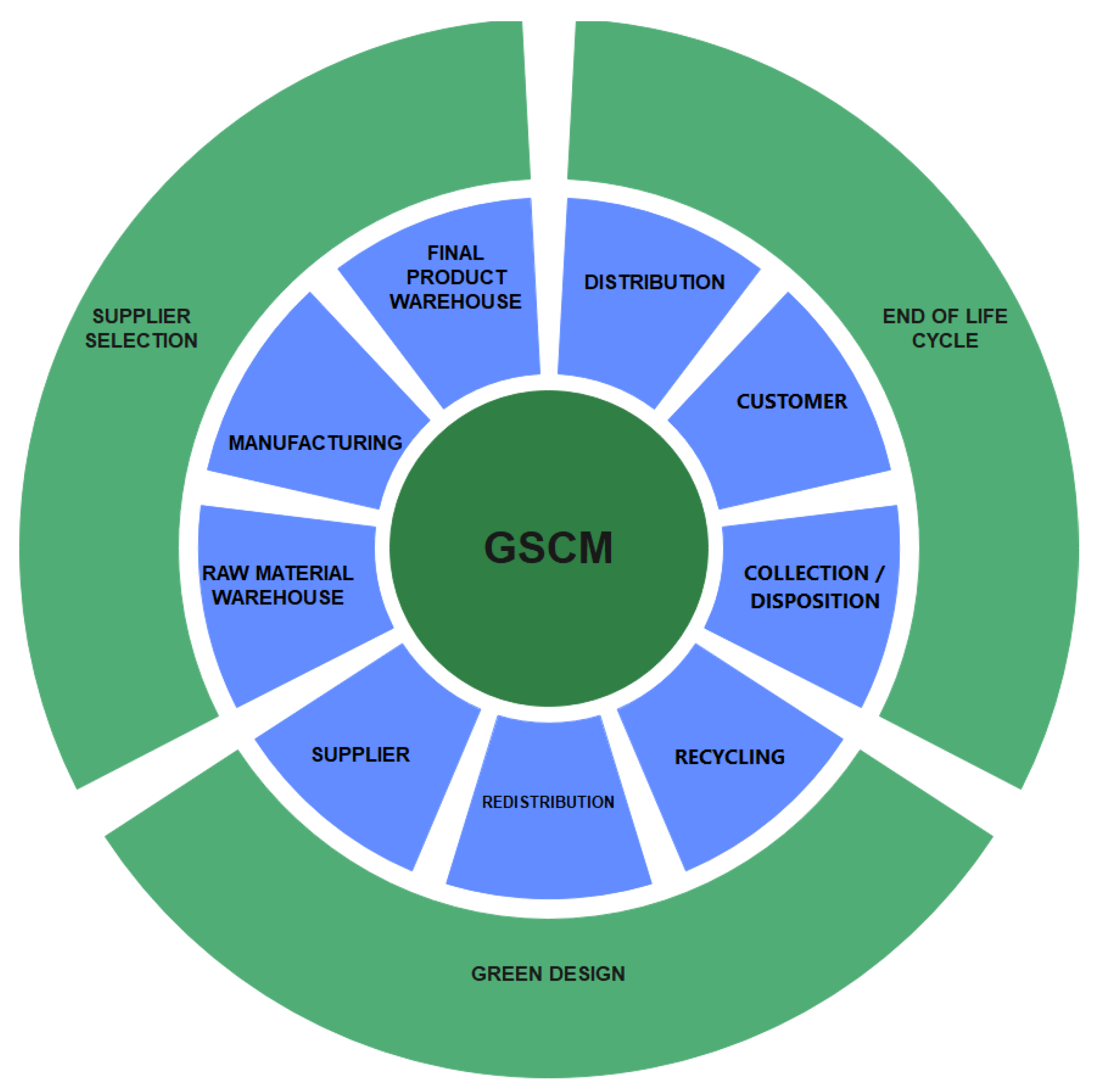

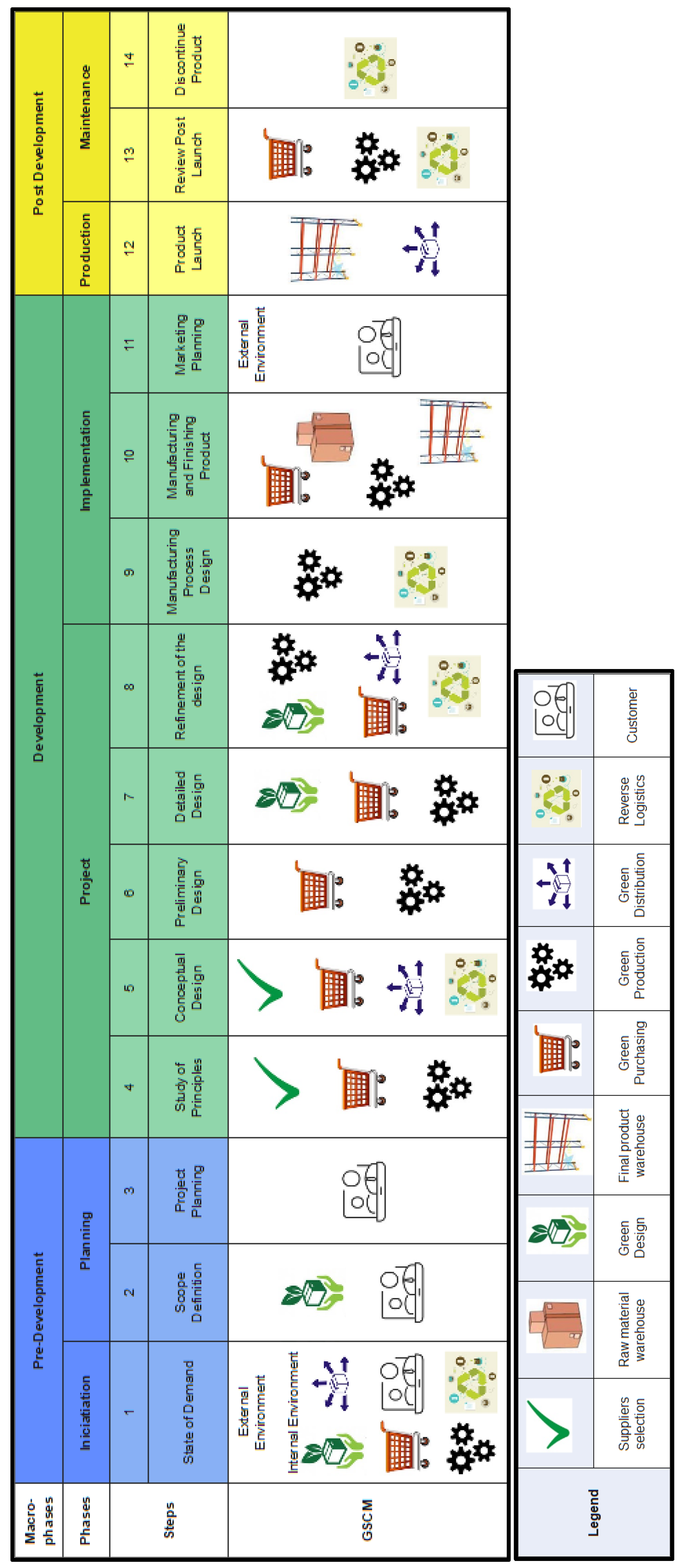

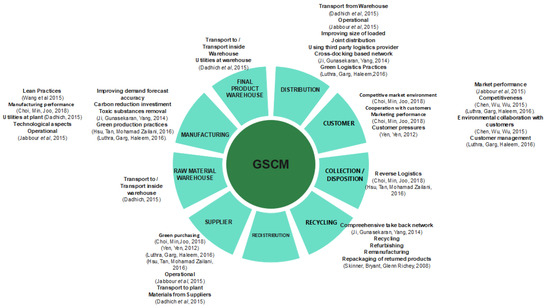

For the elaboration of the preliminary model to be presented in the sequence, important references of the systematic and bibliometric review and content analysis were used, as well as the models presented in this article that composed an update of the publications. After the analysis of the different authors, models, and frameworks, the main GSCM activities [18] and what the authors’ contributions were within the process were identified (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Internal GSCM and the activities in terms of product development.

GSCM is the core process and integrates activities such as (i) purchasing; (ii) raw material storage; (iii) production process; (iv) finished product storage; (v) distribution; (vi) client; (vii) collection; (viii) recycling; and (ix) redistribution. These activities are considered cyclical in a GSCM process because after the activities of collection, recycling, and redistribution there is feedback of the system, which may be through the purchase of inputs that come from recycling.

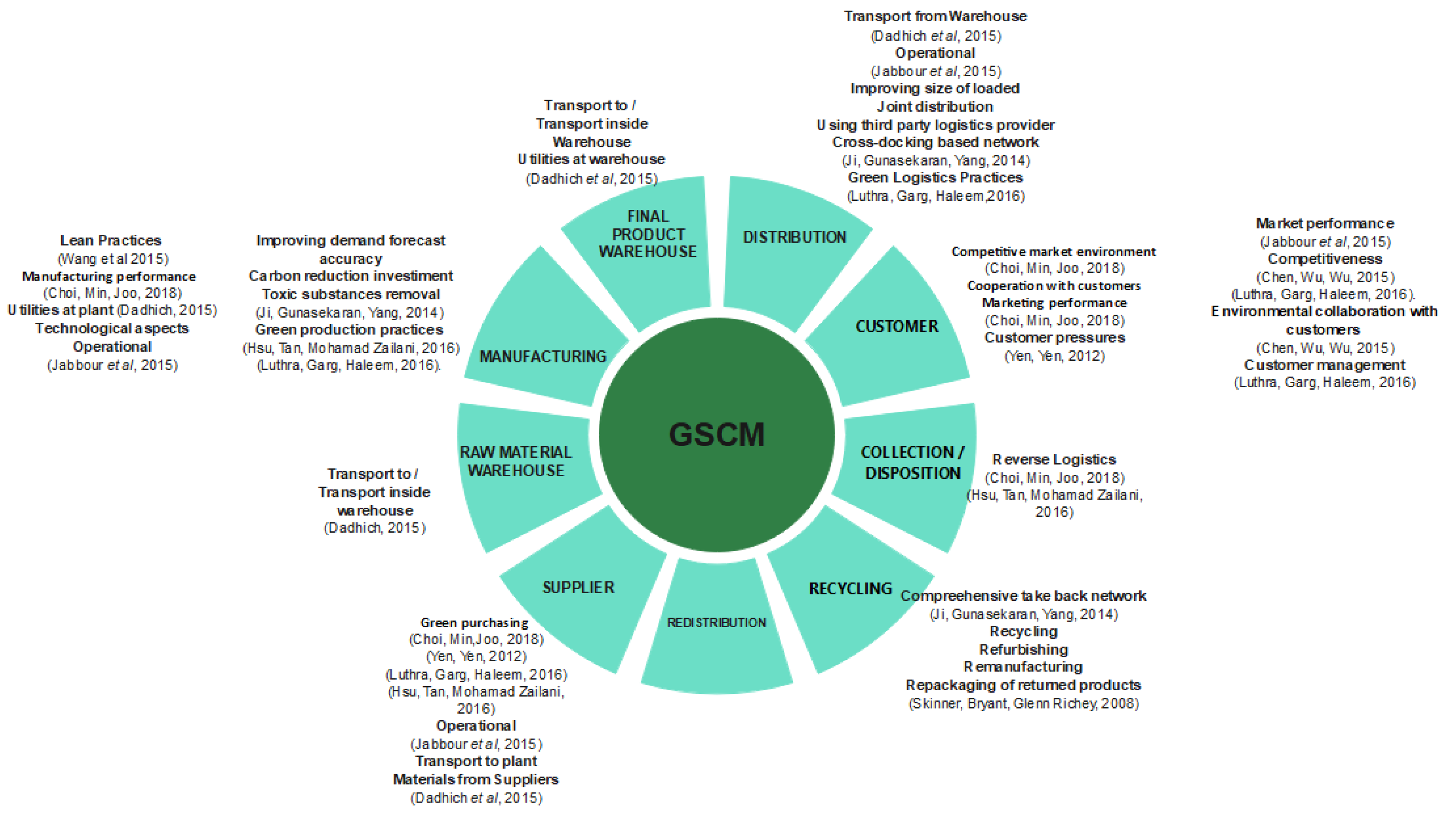

From the analysis of each activity of the supply chain, the environmental criteria were listed for observation so that this activity had a reduced environmental impact. These requirements were obtained by reading the articles and selecting the criteria. It is observed that some authors used the same terminology or very close terminologies to describe a criterion. To obtain reliability, we opted to keep the same terminologies of the authors, even if they seemed to be repetitive in some cases (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

GSCM and the activities of the product development.

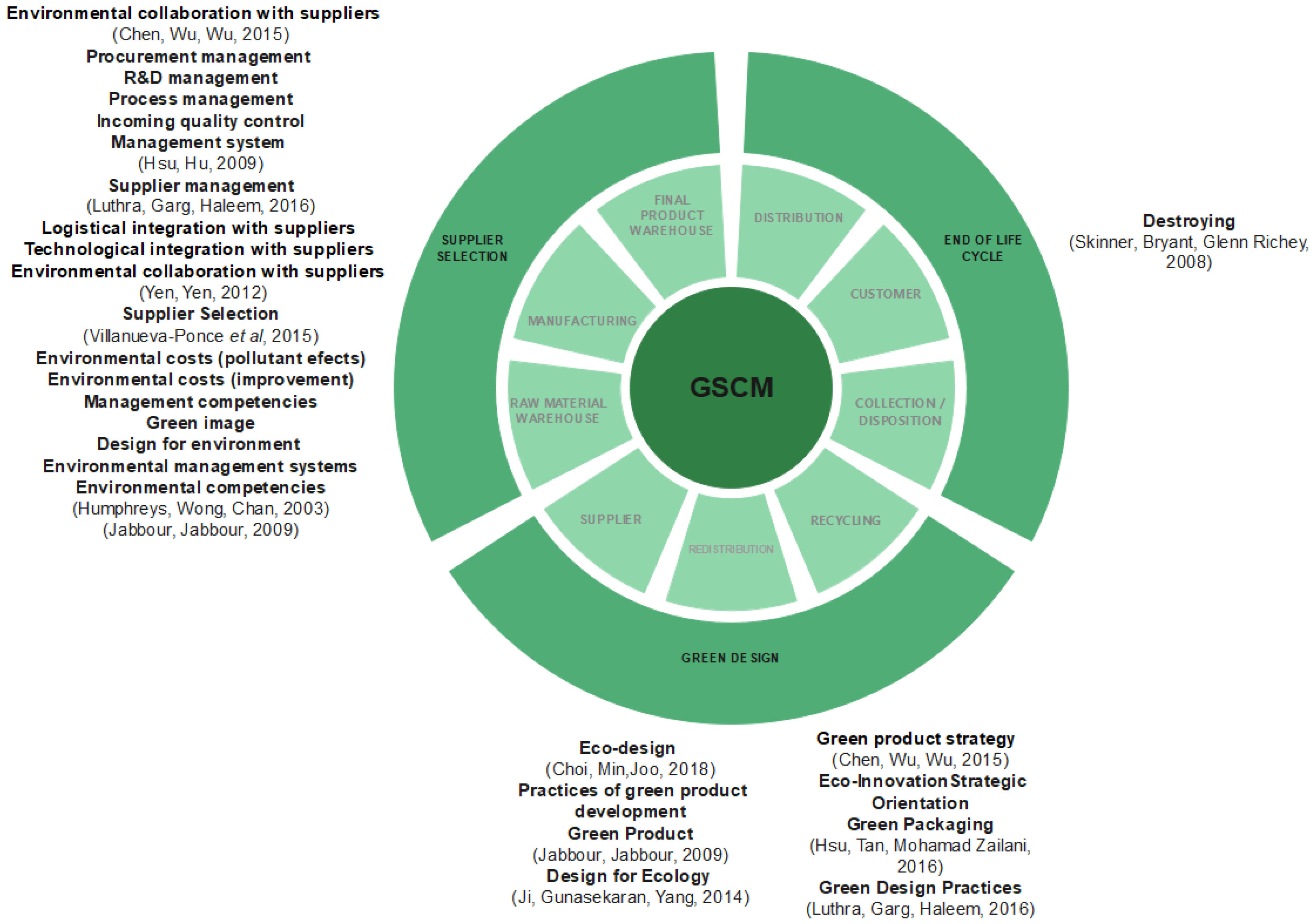

After the analysis of each supply chain activity, the macroprocesses that will guide the supply chain activities were listed. These macroprocesses are guiding towards GSCM; that is, these macroprocesses should be followed so that the GSCM activities are performed. Thus, the macroprocesses are (i) green design; (ii) supplier selection; and (iii) end of product life.

In the same way that the GSCM activities and the main authors’ terminology and reliability were analysed, when the macroprocesses were analysed the environmental criteria were also listed to be observed so that this activity had a reduced environmental impact (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

GSCM and the activities in terms of the product development—macroprocesses and main authors.

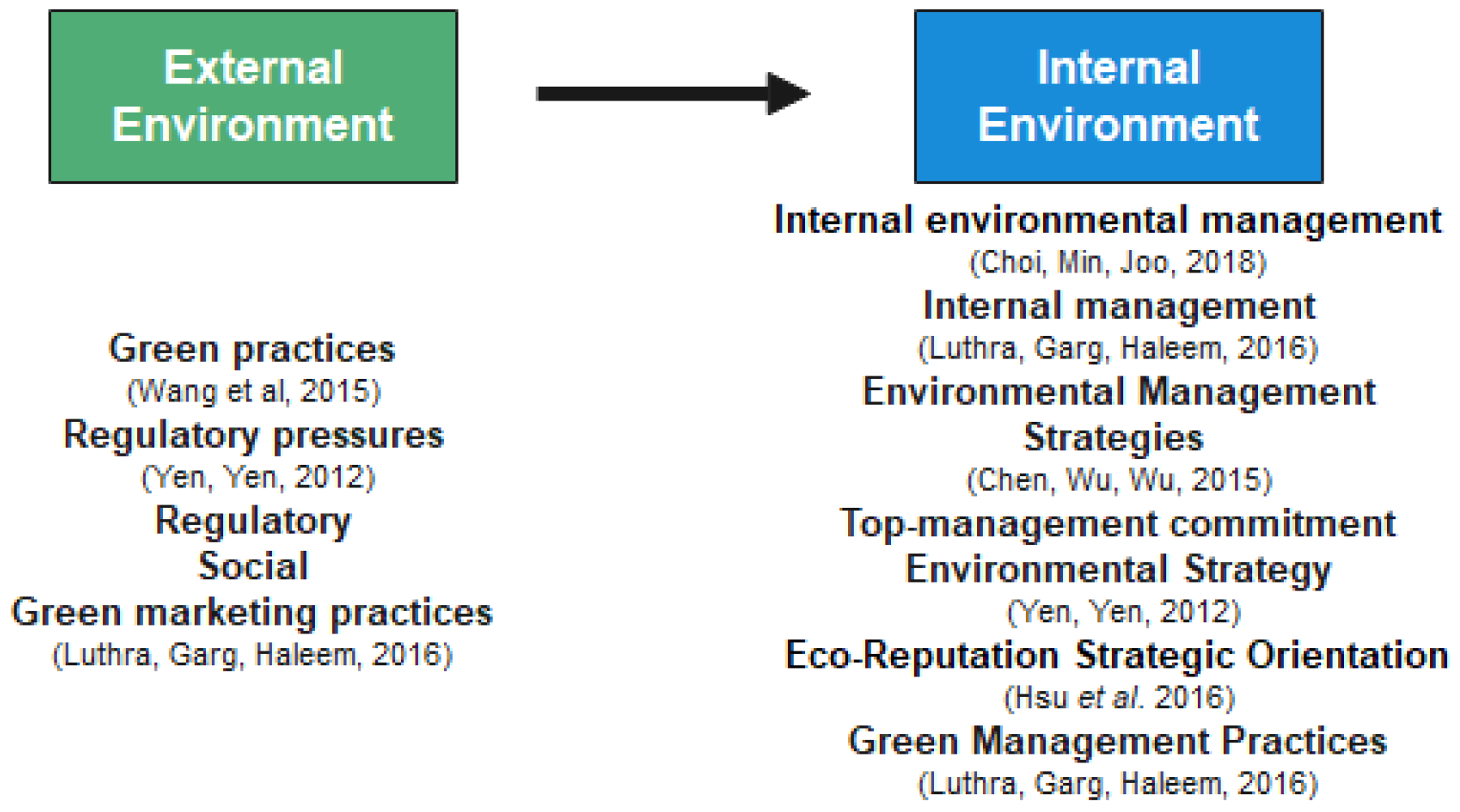

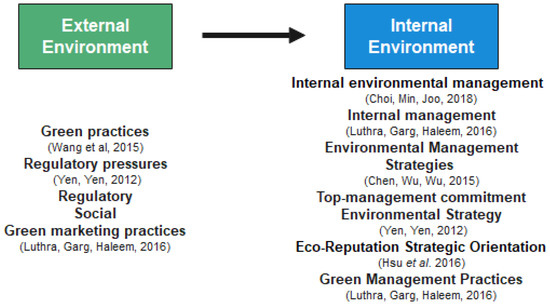

The same logic was followed to search the main authors’ contributions to the GSCM activities, and the macroprocesses were observed in order to obtain the contributions of the internal and external environment. When dealing with the environment, these refer to the drivers, the pressures, and the internal and external regulations that will also guide companies towards better practices at the environmental level (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

GSCM and the activities of the product development—external and internal environment.

4.2. Preliminary Model of Integrated Product Development Process Oriented by GSCM

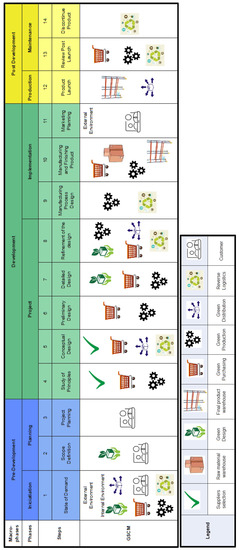

Due to the preference of the authors, after reading and analysing several models, the “model of integrated product development oriented to R&D projects of the Brazilian electricity sector” was taken as a basis because, for the development of this model, a vast amount of research on the published product development models was carried out (Figure 5) [53] The model described brings robust research in which 38 publications are analysed from the year 1962 to 2010; then, the author presents the contributions of the publications for the preparation of the macro-phases, phases, and stages of the model.

Figure 5.

Preliminary model of integrated product development process oriented by green supply chain management.

To associate the IPDP and the GSCM concept, there were classified and analysed activities of the following stages: green design, green purchasing, green production, green manufacturing, green distribution and reverse logistics. Next, the GSCM stages were related to the product development macro phases, phases, and steps (Figure 5).

The product development model was developed through 3 macro-phases, 6 phases and 14 steps (Figure 5). In the Macrophase Pre-development, there are the phases of Initialization and Planning. In the Initialization phase there is the step called the State of Demand (1). Then, the Planning phase has the steps called the Scope Definition (2) and Project Planning (3).

In the Macrophase Development, there are the phases Design and Implementation. In the Design phase the steps are the Study of Principles (4), Conceptual Design (5), Preliminary Design (6), Detailed Design (7), and Refinement of the Design (8). In the Implementation phase, the steps are Manufacturing Process Design (9), Manufacturing and Finishing Product (10), and Marketing Planning (11).

In the Macrophase Post-Development, there are the phases of Production and Maintenance. In the Production phase, the Product Launch (12) is a step. In the Maintenance phase, the steps are Review Post Launch (13) and Discontinue Product (14).

From this preliminary model, highlighted is the need to integrate the GSCM and IPDP approaches in the search for environmentally sustainable product development by companies. Although there are many relevant publications that somehow approach the theme, this article highlights the need for future studies that improve the model by the integration of IPDP and GSCM.

4.3. Relationship of the GSCM’s Internal and External Environments and the Preliminary Model

The construction of the preliminary model (Figure 5) was conceptually based on the existing relationships between the activities existing in the external and internal environments of the GSCM (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4) and the macrophases, phases and, steps of the IPDP model proposed by Pereira and Canciglieri Junior [53]. These relationships are emphasized in the columns “Contribution” and “Macrophases, Phases and steps of the proposed preliminary model” of Table 10.

Table 10.

Relationship of activities between the Green Supply Chain with the macrophases, phases, and steps of the proposed preliminary model.

5. Conclusions

This article presented a preliminary model proposal for an integrated product-development process oriented by green supply chain management. It started with a bibliographic review of the relevant conceptual models in the literature relating IPDP and GSCM. Thereby, this theoretical reference allowed the conception of a preliminary integrated product-development model oriented to green supply chain management (Figure 5).

With the evolution of the research, it was possible to notice the gap in the literature; that is, there were relevant publications that addressed green design, green purchasing, green production, green distribution, and reverse logistics. Some integrated links in the supply chain had some relationships with the products and processes.

The proposed preliminary model is composed of 3 macrophases (Pre-Development, Development, and Post-Development); 6 phases (Initialization, Planning, Project, Implementation, Production, and Maintenance); and 14 steps. These macrophases are subdivided into phases, such as: (i) pre-development—initialization and planning, (ii) development—designing and implementation, and (iii) post development—production and maintenance.

With regard to the Macrophase Pre-Development, the Initialization phase must be responsible for determining the state of demand through a mapping of the product that will be developed, taking into account the needs of the users and the raw materials available in the market that are environmentally sustainable. It should have background knowledge about development and the development of the products previously carried out by the company. This process is essential for companies to visualize the development planning of their products with the objective of and the orientation towards the environmental preservation of the planet without losing the consumer’s desire. The Planning phase has two stages, scope definition and project planning. In the scope definition stage, a study of the market needs, the raw materials, and the technologies available on the market is carried out, and from this, possible solutions for the product are defined. Additionally, the strategies that are suitable are selected so that a product that meets the GSCM requirements is developed. Finally, in this macrophase, the project planning stage, the schedule, the contract with the demand forecast, and the product details must be defined.

With regard to the Macrophase Development, the Design phase has five steps, which are the study of principles, conceptual design, preliminary design, detailed design, and refinement of design. This phase comprises the beginning of the design execution through the study of principles, scope analysis, and the investigation of possible solutions for the product to be developed, defining the design specifications and considering the expectations and desires of the users, the company’s strategies, market strategies, raw materials, and the equipment available for product development.

Conceptual design is the stage where suppliers are involved in jointly bringing solutions to the customer. The project specification will be the basis of this stage. The product design, dimensions, materials, and equipment to be used are established, as well as the check on whether the GSCM requirements and the customer’s needs are being met. The preliminary design step takes place after gathering the data obtained from the conceptual project. At this stage, the shape of the product is defined, and from then on, the basic functions of the product, the dimensions, and the materials will be defined, and the steps of the manufacturing process will be elaborated.

In the detailed design stage, the planning of the final product is prepared, based on prototype testing, and the study of the possible raw materials and components that can make the product environmentally sustainable takes place. Additionally, in the refinement of the design stage, the corrections and alterations to the project are carried out, based on the prototype tests. A prototype is built very close to the final project, and the documents relating to product design, the calculations, and the list of the materials and steps of the manufacturing process are changed.

The implementation phase has three stages, which are the manufacturing process design, manufacturing and finishing the product, and the marketing planning. The manufacturing process design stage will be carried out from the prototype and the pre-established project in the previous phases. At this stage, the production process is planned, thus defining the stages and the sequence of the production process, the machines and equipment to be used, the quality standard, and the environmental standards.

The manufacturing and finishing-product step is carried out based on the definition of the steps of the production process and the suppliers involved. A pilot batch is produced to verify production in scale, and if necessary, changes are made to the product in order to make all the adjustments to the production line. At this stage, the market insertion and marketing planning plans are also defined.

In the marketing planning stage, the insertion of the product in the market is defined based on the product scope, and the strengths, weaknesses, threats, and opportunities of the product are also established (SWOT analysis).

With regard to the Macrophase Development, the production phase has the product launch step, in which the strategy for launching the product on the market is defined. The maintenance phase has a post-launch review and discontinues the product steps. In the post-launch review stage, changes and/or improvements are made to the production line, based on the collected and systematized data. In addition, in the discontinue product step, measures are applied to withdraw the product from the market and close production, based on market monitoring. As this is a product with an environmental appeal, the instructions for recycling and reuse must be clear to final consumers for the correct disposal of the product.

The models presented were the reference base of the preliminary model that integrates IPDP and GSCM. The model will contribute to companies as it considers the criteria to reduce the environmental impact of products in the different activities of GSCM within IPDP in an integrated way. However, even though the contribution of this article has been in the presentation of the conception and design process of the preliminary IPDP model integrated with the GSCM concepts, it is possible to see which actions the product-development companies with a focus on sustainability can implement and improve to make their processes producible in a sustainable way. There are certainly other points yet to be explored. The authors would like to apply the preliminary model in different segments of the industry to transform it into a definitive model, and this will be the object of future exploration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Y.U.R. and O.C.J.; methodology, A.Y.U.R. and O.C.J.; validation, A.Y.U.R., O.C.J., A.L.S. and M.R.; investigation, A.Y.U.R. and O.C.J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Y.U.R.; writing—review and editing, A.Y.U.R., O.C.J., A.L.S. and M.R.; supervision, O.C.J. and M.R.; project administration, O.C.J.; funding acquisition, O.C.J. and A.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The researchers would like to thank the Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná (PUCPR), the Polytechnic School, the Industrial and Systems Engineering Graduate Program (PPGEPS), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq–Brazil) and Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES – Brazil) for the funding and structure of this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Population. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/br/ (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- População Mundial Atingiu 7,6 Bilhões de Habitantes. Available online: https://news.un.org/pt/story/2017/06/1589091-populacao-mundial-atingiu-76-bilhoes-de-habitantes (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Uemura Reche, A.Y.; Canciglieri Junior, O.; Estorilio, C.C.A.; Rudek, M. Integrated product development process and green supply chain management: Contributions, limitations and applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura Reche, A.Y.; Canciglieri Junior, O.; Rudek, M. The importance green supply chain management approach in the Integrated product development process. In Integrating Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-59974-4. [Google Scholar]

- Canciglieri Junior, O.; Estorilio, C.C.A.; Reche, A.Y.U. How Can Green Supply Chain Management Contribute to the Product Development Process. In Transdisciplinary Engineering Methods for Social Innovation of Industry 4.0, 1st ed.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 7, pp. 1175–1183. [Google Scholar]

- ABNT—Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas. ISO 14001:20115—Sistema de Gestão Ambiental—Requisitos com Orientações para Uso. ABNT, Rio de Janeiro. Available online: https://www.iso.org/iso-14001-environmental-management.html (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Green, K.W.; Zelbst, P.J.; Meacham, J.; Bhadauria, V.S. Green supply chain management practices: Impact on performance. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellitto, M.A.; Borchardt, M.; Pereira, G.M.; de Jesus Pacheco, D.A. Gestão de cadeias de suprimentos verdes: Quadro de trabalho. Produção Online 2013, 13, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mollenkopf, D.; Stolze, H.; Tate, W.L.; Ueltschy, M. Green, lean, and global supply chains. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2010, 40, 14–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Wu, Y.J.; Wu, T. Moderating effect of environmental supply chain collaboration. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2015, 45, 959–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, Y.X.; Yen, S.Y. Top-management’s role in adopting green purchasing standards in high-tech industrial firms. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Tan, K.-C.; Mohamad Zailani, S.H. Strategic orientations, sustainable supply chain initiatives, and reverse logistics. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2016, 36, 86–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, P.K.; Wong, Y.K.; Chan, F.T.S. Integrating environmental criteria into the supplier selection process. J. Mater. Processing Technol. 2003, 138, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, A.B.L.S.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Are supplier selection criteria going green? Case studies of companies in Brazil. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2009, 109, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.W.; Hu, A.H. Applying hazardous substance management to supplier selection using analytic network process. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.; Gunasekaran, A.; Yang, G. Constructing sustainable supply chain under double environmental medium regulations. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura Reche, A.Y.; Canciglieri, O.; Estorilio, C.C.A.; Rudek, M. Green Supply Chain Management and the Contribution to Product Development Process. In Walter Leal Filho, 1st ed.; Paulo, R., de Brito, B., Frankenberger, F., Eds.; World Sustainability Series; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Ponce, R.; Avelar-Sosa, L.; Alvarado-Iniesta, A.; Cruz-Sánchez, V.G. The green supplier selection as a key element in a supply chain: A review of cases studies. DYNA 2015, 82, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-B.; Min, H.; Joo, H.-Y. Examining the inter-relationship among competitive market environments, green supply chain practices, and firm performance. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 1025–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadhich, P.; Genovese, A.; Kumar, N.; Acquaye, A. Developing sustainable supply chains in the UK construction industry: A case study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 164, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, L.R.; Bryant, P.T.; Glenn Richey, R. Examining the impact of reverse logistics disposition strategies. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 518–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Garg, D.; Haleem, A. The impacts of critical success factors for implementing green supply chain management towards sustainability: An empirical investigation of Indian automobile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 121, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portal de Periódicos CAPES/MEC. Available online: https://www-periodicos-capes-gov-br.ezl.periodicos.capes.gov.br/index.php?option=com_pcollection&Itemid=105 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Graham, S. Antecedents to environmental supply chain strategies: The role of internal integration and environmental learning. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 197, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanot, N.; Rao, P.V.; Deshmukh, S.G. An integrated approach for analysing the enablers and barriers of sustainable manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 4412–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan Shankar, K.; Kannan, D.; Udhaya Kumar, P. Analyzing sustainable manufacturing practices e a case study in Indian context. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 1332–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrega, M.; Forkmann, S.; Zaefarian, G.; Henneberg, S.C. Networking capability in supplier relationships and its impact on product innovation and firm performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 577–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M.; Silvestri, R.; Contò, F.; Pellegrini, G. Understanding the relationship between green approach and marketing innovations tools in the wine sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 4085–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellacci, F.; Lie, C.M. A taxonomy of green innovators: Empirical evidence from South Korea. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 1036–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzoli, C.; Ceschin, F.; Diehl, J.C.; Kohtala, C. New design challenges to widely implement ‘sustainable product-service systems’. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, J.; Germain, R. Understanding the relationships of integration capabilities, ecological product design, and manufacturing performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 92, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiyazhagan, K.; Diabat, A.; Al-Refaie, A.; Xu, L. Application of analytical hierarchy process to evaluate pressures to implement green supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Jugend, D.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Gunasekaran, A.; Latan, H. Green product development and performance of Brazilian firms: Measuring the role of human and technical aspects. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, K.; Kannan, D.; Diabat, A.; Jha, P.C. A multi-criteria optimization approach to manage environmental issues in closed loop supply chain network design. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 100, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, M.; Machuca, J.A.D.; Flynn, E.J.; Perez de los Ríos, J.L. Aligning product characteristics and the supply chain process e a normative perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 161, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Choudhary, A.; Cai, X.; Yang, K. Value stream mapping to reduce the lead-time of a product development process. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 160, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Jim Wu, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.J.; Goh, M. Aligning supply chain strategy with corporate environmental strategy: A contingency approach. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, R.G.; Musgrove, C.F.; Gillison, S.T.; Gabler, C.B. The effects of environmental focus and program timing on green marketing performance and the moderating role of resource commitment. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 1246–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrettle, S.; Hinz, A.; Scherrer -Rathje, M.; Friedli, T. Turning sustainability into action: Explaining firms’ sustainability efforts and their impact on firm performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Kaliyan, M.; Kannan, D.; Haq, A.N. Barriers analysis for green supply chain management implementation in Indian industries using analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Keung Lai, K.; Sun, H.; Chen, Y. The impact of supplier integration on customer integration and new product performance: The mediating role of manufacturing flexibility under trust theory. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabat, A.; Kannan, D.; Mathiyazhagan, K. Analysis of enablers for implementation of sustainable supply chain management e a textile case. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 83, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]