Core Self-Evaluation, Emotional Reactivity to Interpersonal Conflict, and Subjective Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Horizontal Collectivism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Core Self-Evaluation and Emotional Reactivity to Interpersonal Conflict

2.2. The Moderating Role of Horizontal Collectivism

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analytic Strategy

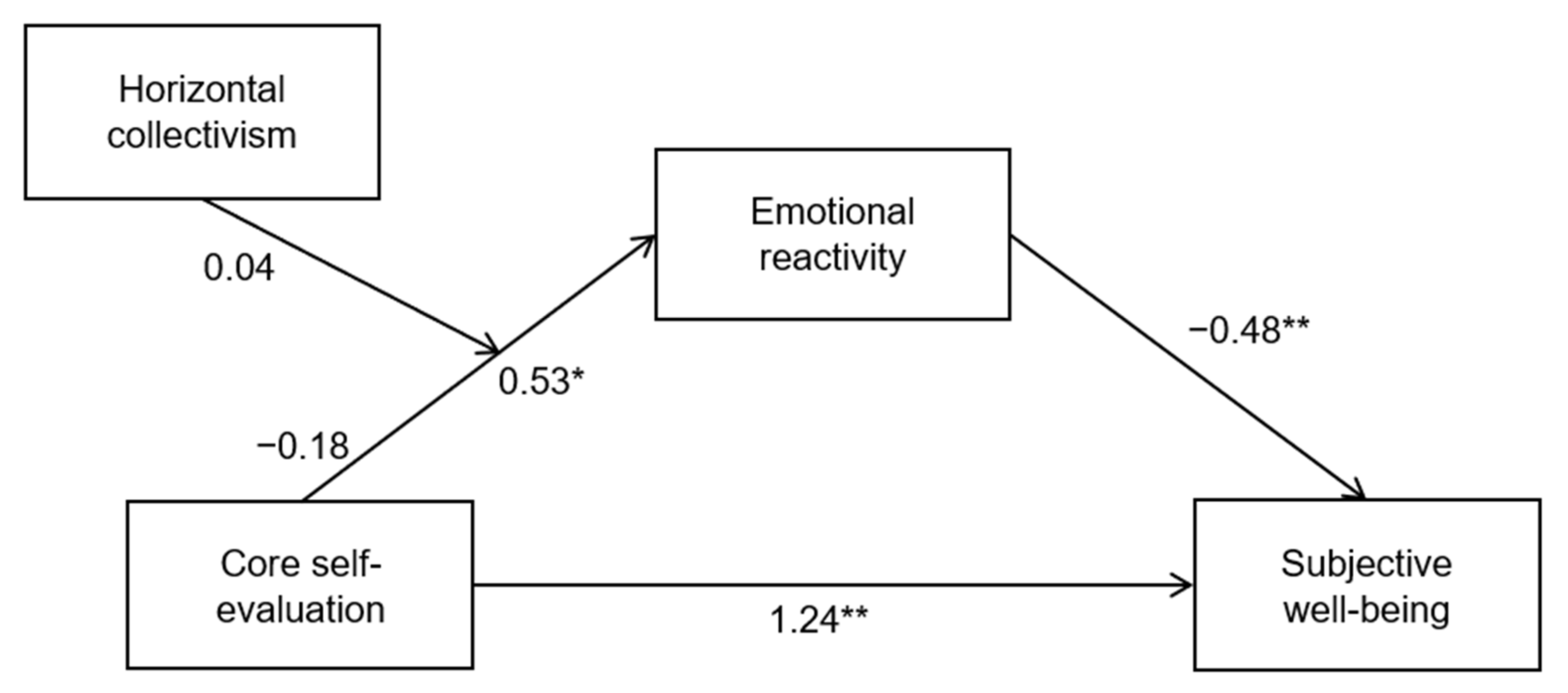

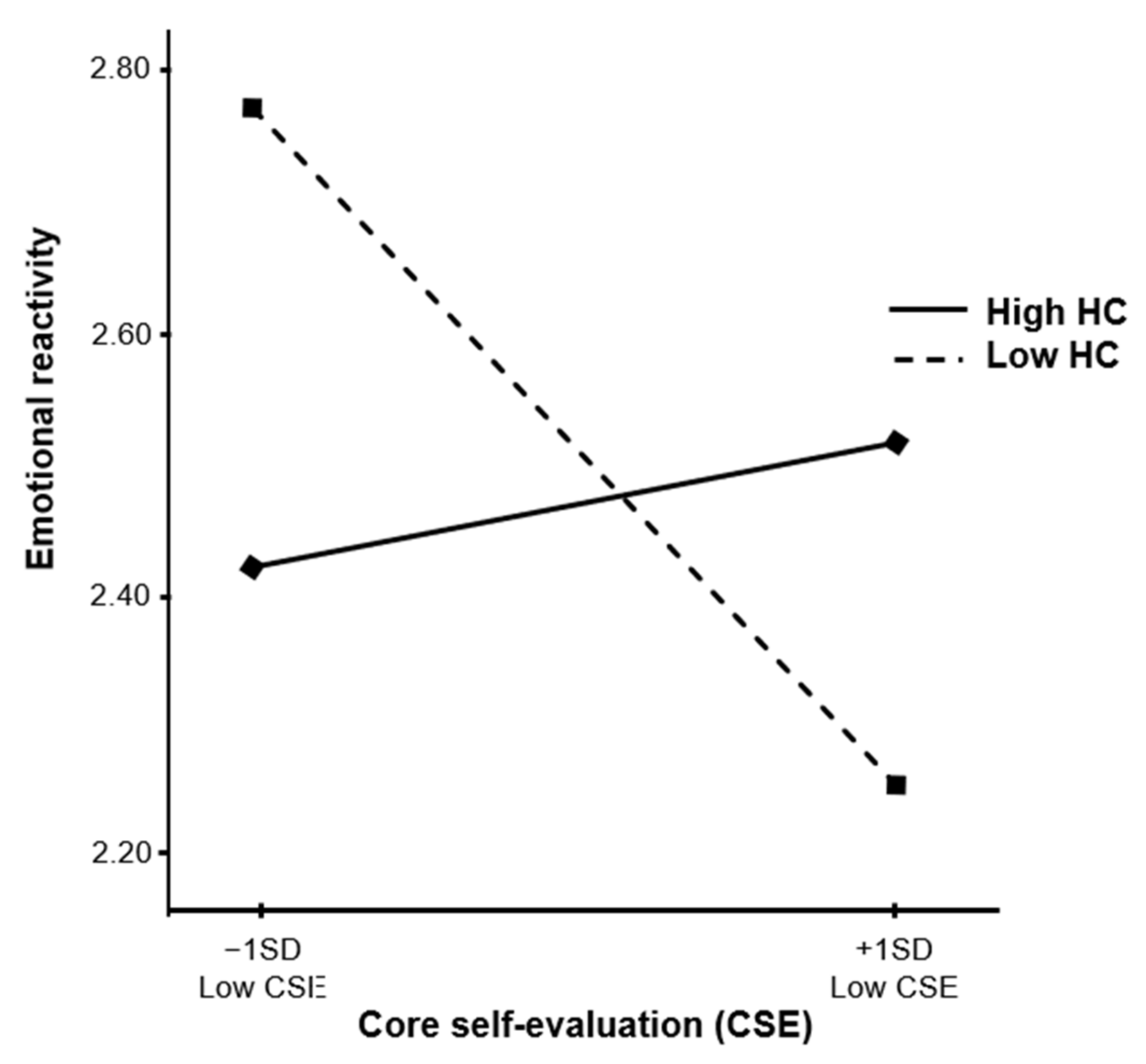

4. Results

5. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kansky, J.; Diener, E. Benefits of well-being: Health, social relationships, work, and resilience. J. Posit. Psychol. Wellbeing 2017, 1, 129–169. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Chan, M.Y. Happy People Live Longer: Subjective Well-Being Contributes to Health and Longevity: Health Benefits of Happiness. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2011, 3, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Thapa, S.; Tay, L. Positive Emotions at Work. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2020, 7, 451–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Positive Emotions Broaden and Build; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 47, pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushlev, K.; Heintzelman, S.J.; Lutes, L.D.; Wirtz, D.; Kanippayoor, J.M.; Leitner, D.; Diener, E. Does Happiness Improve Health? Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A.; Kenny, M.E. Promoting Well-Being: The Contribution of Emotional Intelligence. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor-Smith, J.K.; Compas, B.E. Coping as a Moderator of Relations between Reactivity to Interpersonal Stress, Health Status, and Internalizing Problems. Cognit. Ther. Res. 2004, 28, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatough, E.M.; Chang, C.-H. Effective Coping with Supervisor Conflict Depends on Control: Implications for Work Strains. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, D.; Falco, A.; De Carlo, A.; Benevene, P.; Comar, M.; Tongiorgi, E.; Bartolucci, G.B. The Mediating Role of Interpersonal Conflict at Work in the Relationship between Negative Affectivity and Biomarkers of Stress. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.M. Resilience and Vulnerability to Daily Stressors Assessed via Diary Methods. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 14, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N.; DeLongis, A.; Kessler, R.C.; Schilling, E.A. Effects of Daily Stress on Negative Mood. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Johnson, M.D.; Judge, T.A.; Keeney, J. A Within-Individual Study of Interpersonal Conflict as a Work Stressor: Dispositional and Situational Moderators: Interpersonal Conflict at Work. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiro, M.J.; Bettis, A.H.; Compas, B.E. College Students Coping with Interpersonal Stress: Examining a Control-Based Model of Coping. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2017, 65, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birditt, K.S.; Polenick, C.A.; Luong, G.; Charles, S.T.; Fingerman, K.L. Daily Interpersonal Tensions and Well-Being among Older Adults: The Role of Emotion Regulation Strategies. Psychol. Aging 2020, 35, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrshek-Schallhorn, S.; Stroud, C.B.; Mineka, S.; Hammen, C.; Zinbarg, R.E.; Wolitzky-Taylor, K.; Craske, M.G. Chronic and Episodic Interpersonal Stress as Statistically Unique Predictors of Depression in Two Samples of Emerging Adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2015, 124, 918–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Judge, T.A.; Scott, B.A. The Role of Core Self-Evaluations in the Coping Process. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.K.; Chen, D.-Y.; Lin, B.Y.-J. Determinants and Effects of Medical Students’ Core Self-Evaluation Tendencies on Clinical Competence and Workplace Well-Being in Clerkship. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Tai, K. Family Incivility and Job Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model of Psychological Distress and Core Self-Evaluation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.J.; Harvey, P.; Kacmar, K.M. Do Social Stressors Impact Everyone Equally? An Examination of the Moderating Impact of Core Self-Evaluations. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009, 24, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welbourne, J.L.; Gangadharan, A.; Sariol, A.M. Ethnicity and Cultural Values as Predictors of the Occurrence and Impact of Experienced Workplace Incivility. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; Ferris, D.L.; Johnson, R.E.; Rosen, C.C.; Tan, J.A. Core Self-Evaluations: A Review and Evaluation of the Literature. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 81–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Erez, A.; Bono, J.E.; Thoresen, C.J. The Core Self-Evaluations Scale (CSES): Development of a measure. Personal. Psychol. 2003, 56, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, L.E.; Maner, J.K. Does Self-Threat Promote Social Connection? The Role of Self-Esteem and Contingencies of Self-Worth. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Baumeister, R.F. The Nature and Function of Self-Esteem: Sociometer Theory. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 32, pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Turiano, N.A.; Infurna, F.J.; Lachman, M.E.; Chapman, B.P. Lifetime Trauma, Perceived Control, and All-Cause Mortality: Results from the Midlife in the United States Study. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohs, K.D.; Finkenauer, C.; Baumeister, R.F. The Sum of Friends’ and Lovers’ Self-Control Scores Predicts Relationship Quality. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2011, 2, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; Coon, H.M.; Kemmelmeier, M. Rethinking Individualism and Collectivism: Evaluation of Theoretical Assumptions and Meta-Analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Individualism-Collectivism and Personality. J. Personal. 2001, 69, 907–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, E.; Jung, H.; Park, I.-J. Psychological Factors Linking Perceived CSR to OCB: The Role of Organizational Pride, Collectivism, and Person–Organization Fit. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T.M.; Triandis, H.C.; Bhawuk, D.P.S.; Gelfand, M.J. Horizontal and Vertical Dimensions of Individualism and Collectivism: A Theoretical and Measurement Refinement. Cross Cult. Res. 1995, 29, 240–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C.; Gelfand, M.J. Converging Measurement of Horizontal and Vertical Individualism and Collectivism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.G.; Jin, P.; English, A.S. Collectivism Predicts Mask Use during COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2021793118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfundmair, M.; Aydin, N.; Frey, D.; Echterhoff, G. The Interplay of Oxytocin and Collectivistic Orientation Shields against Negative Effects of Ostracism. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 55, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Komarraju, M.; Dollinger, S.J.; Lovell, J.L. Individualism-collectivism in Horizontal and Vertical Directions as Predictors of Conflict Management Styles. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2008, 19, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, S.; Guzel, S.; Ulutas, D.A. The Relationship between Individualism, Collectivism and Conflict Handling Styles of Healthcare Employees. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2019 Prognostics and System Health Management Conference (PHM-Paris), Paris, France, 2–5 May 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.Y.; Fung, H.H. A Dynamic Process Model of Forgiveness: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2011, 15, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniati, N.M.T.; Worthington, E.L.; Kristi Poerwandari, E.; Ginanjar, A.S.; Dwiwardani, C. Forgiveness in Javanese Collective Culture: The Relationship between Rumination, Harmonious Value, Decisional Forgiveness and Emotional Forgiveness. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 20, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riek, B.M.; Mania, E.W. The Antecedents and Consequences of Interpersonal Forgiveness: A Meta-Analytic Review. Personal. Relatsh. 2012, 19, 304–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Suh, Y. Conflict Mindset. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 27, 389–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, R.; Lepak, D.P.; Wang, H.; Takeuchi, K. An Empirical Examination of the Mechanisms Mediating between High-Performance Work Systems and the Performance of Japanese Organizations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.M.; McGonagle, K.A.; Cate, R.C.; Kessler, R.C.; Wethington, E. Psychosocial Moderators of Emotional Reactivity to Marital Arguments: Results from a Daily Diary Study. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2002, 34, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L.R. Affects Balance Scale; Clinical Psychometrics Research: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Niemiec, C.P. It’s not just the amount that counts: Balanced need satisfaction also affects well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Regression-Based Statistical Mediation and Moderation Analysis in Clinical Research: Observations, Recommendations, and Implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 98, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F.; Scharkow, M. The Relative Trustworthiness of Inferential Tests of the Indirect Effect in Statistical Mediation Analysis: Does Method Really Matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pek, J.; Flora, D.B. Reporting Effect Sizes in Original Psychological Research: A Discussion and Tutorial. Psychol. Methods 2018, 23, 208–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Extremera, N.; Sánchez-Álvarez, N.; Rey, L. Pathways between Ability Emotional Intelligence and Subjective Well-Being: Bridging Links through Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, A.J.; Salovey, P.; Achor, S. Rethinking Stress: The Role of Mindsets in Determining the Stress Response. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 716–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, T.J.; Miller, G.E. The Interpersonally Sensitive Disposition and Health: An Integrative Review. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 941–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.44 | 0.50 | ||||||

| 2. Issue importance | 3.29 | 1.16 | −0.05 | |||||

| 3. Relationship closeness | 4.07 | 1.00 | −0.07 | 0.21 ** | ||||

| 4. Core self-valuation | 3.46 | 0.53 | 0.20 ** | −0.06 | 0.02 | |||

| 5. Horizontal collectivism | 3.78 | 0.52 | −0.01 | 0.13 * | 0.18 ** | 0.21 ** | ||

| 6. Emotional reactivity | 2.52 | 0.98 | −0.02 | 0.41 ** | 0.13 * | −0.15 * | 0.01 | |

| 7. Subjective well-being | 3.58 | 1.84 | −0.01 | −0.11 | −0.01 | 0.40 ** | 0.11 | −0.31 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, S. Core Self-Evaluation, Emotional Reactivity to Interpersonal Conflict, and Subjective Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Horizontal Collectivism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052515

Oh S. Core Self-Evaluation, Emotional Reactivity to Interpersonal Conflict, and Subjective Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Horizontal Collectivism. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):2515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052515

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Sunyoung. 2022. "Core Self-Evaluation, Emotional Reactivity to Interpersonal Conflict, and Subjective Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Horizontal Collectivism" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052515

APA StyleOh, S. (2022). Core Self-Evaluation, Emotional Reactivity to Interpersonal Conflict, and Subjective Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Horizontal Collectivism. Sustainability, 14(5), 2515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052515