Connecting the Dots between Social Care and Healthcare for the Sustainability Development of Older Adult in Asia: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. The Review Protocol

2.2. Systematic Search Strategies

2.3. Selection Criteria

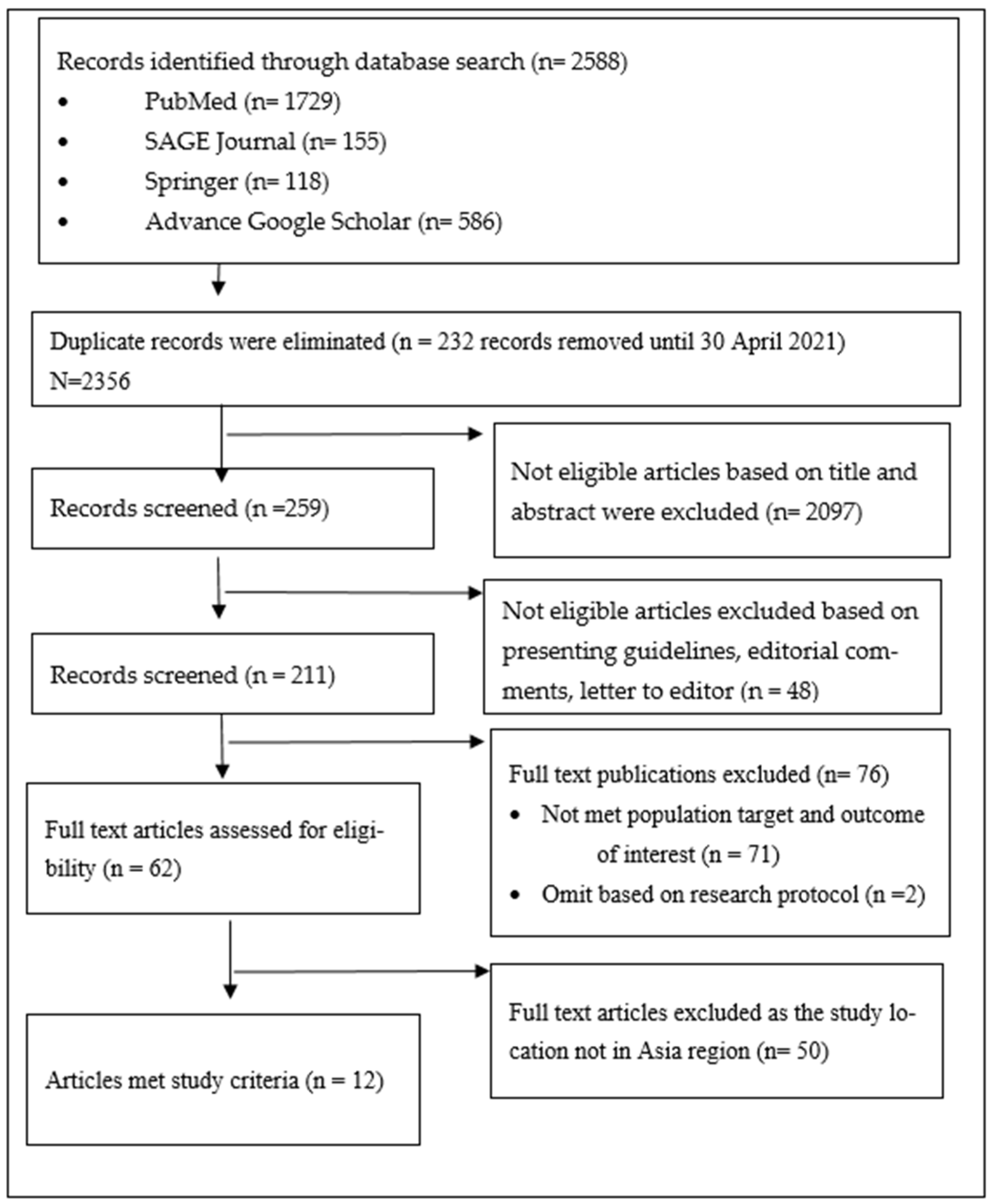

2.4. Selection of Articles

2.5. Risk of Bias

2.6. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Review Selection

3.2. Types of Reviews

3.3. Focus of Reviews

4. Discussion

4.1. Strength and Limitation

4.2. Implication and Sustainability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations; Department of Economic and Social Affairs; Population Division. World Population Ageing 2019 (ST/ESA/SER.A/444); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Tiraphat, S.; Buntup, D.; Munisamy, M.; Nguyen, T.H.; Yuasa, M.; Aung, M.N.; Myint, A.H. Age-Friendly Environments in ASEAN Plus Three: Case Studies from Japan, Malaysia, Myanmar, Vietnam, and Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IndexMundi. 2021. Available online: https://www.indexmundi.com/factbook/compare/malaysia.indonesia.thailand.singapore/demographics (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Asian Development Bank. Country Diagnostic Study on Long Term Care in Thailand. 2020. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/661736/thailand-country-diagnostic-study-long-term-care.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Damery, S.; Flanagan, S.; Combes, G. The effectiveness of interventions to achieve co-ordinated multidisciplinary care and reduce hospital use for people with chronic diseases: Study protocol for a systematic review of reviews. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ambigga, K.S.; Ramli, A.S.; Suthahar, A.; Tauhid, N.; Clearihan, L.; Browning, C. Bridging the gap in ageing: Translating policies into practice in Malaysian Primary Care. Asia Pac. Fam. Med. 2011, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scott, T.; Mackenzie, C.S.; Chipperfield, J.G.; Sareen, J. Mental health service use among Canadian older adults with anxiety disorders and clinically significant anxiety symptoms. J. Aging Ment. Health 2010, 14, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balezdrova, N.; Choi, D.; Lam, B. ‘Invisible Minorities’: Exploring Improvement Strategies for Social Care Services aimed at Elderly Immigrants in the UK using Co-Design Methods. In Proceedings of the International Association of Societies of Design Research Conference, Manchester, UK, 2–5 September 2019; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Eason, K.; Waterson, P.; Davda, P. The sociotechnical challenge of integrating Telehealth and telecare into health and social care for the elderly. Int. J. Sociotechnol. Knowl. Dev. 2013, 5, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lapre, F.; Stevenson, D.; Leser, M.; Horecky, I.J.; Kaserer, B.; Mattersberger, M. Long-Term Care 2030. European Ageing Network. 2019. Available online: https://www.ecreas.eu/uimg/ecreasportal/b80760_att-report-ean-ltc-2030-digital.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- National Institute on Aging. “National Institute of Health. US Deparment of Health and Human Services”. NIH. 2017. Available online: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-long-termcare (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- World Health Organization. Framework on Integrated, People-Centred Health Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Strehlenert, H.; Richter-Sundberg, L.; Nyström, M.E.; Hasson, H. Evidence-informed policy formulation and implementation: A comparative case study of two national policies for improving health and social care in Sweden. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018, User Guide; Registration of Copyright (#1148552); Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018.

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomized or non-randomized studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malterud, K.; Bjelland, A.K.; Elvbakken, K.T. Systematic reviews for policy-making – critical reflections are needed. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, A.M.; Valentijn, P.P.; Thiyagarajan, J.A.; de Carvalho, I.A. Elements of integrated care approaches for older people: A review of reviews. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, K.S.; Dwyer, A.; Ramelet, A.-S. International practice settings, interventions and outcomes of nurse practitioners in geriatric care: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 78, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirst, M.; Im, J.; Burns, T.; Baker, G.R.; Goldhar, J.; O’Campo, P.; Wojtak, A.; Wodchis, W.P. What works in implementation of integrated care programs for older adults with complex needs? A realist review. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2017, 29, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stoop, A.; Lette, M.; Van Gils, P.F.; Nijpels, G.; Baan, C.A.; de Bruin, S. Comprehensive geriatric assessments in integrated care programs for older people living at home: A scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, e549–e566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Threapleton, D.E.; Chung, R.Y.; Wong, S.Y.-S.; Wong, E.; Chau, P.; Woo, J.; Chung, V.C.; Yeoh, E.-K. Integrated care for older populations and its implementation facilitators and barriers: A rapid scoping review. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2017, 29, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Tang, W. The community-based integrated care system in Japan: Health care and nursing care challenges posed by super-aged society. Biosci. Trends 2019, 13, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du, P.; Wang, Y.M. Population ageing and the development of social care service systems for older persons in China. Int. J. Ageing Dev. Ctries. 2016, 1, 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cassum, L.A.; Cash, K.; Qidwai, W.; Vertejee, S. Exploring the experiences of the older adults who are brought to live in shelter homes in Karachi, Pakistan: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Ding, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhu, S.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Zhou, R.; Yu, Y. The adaptation of older adults’ transition to residential care facilities and cultural factors: A meta-synthesis. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, M.T.; Marshall, A.; Mittinty, M.M.; Harvey, G. What does integrated care mean from an older person’s perspective? A scoping review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noda, S.; Hernandez, P.M.R.; Sudo, K.; Takahashi, K.; Woo, N.E.; Chen, H.; Inaoka, K.; Tateishi, E.; Affarah, W.S.; Kadriyan, H.; et al. Service Delivery Reforms for Asian Ageing Societies: A Cross-Country Study Between Japan, South Korea, China, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines; Ubiquity Press, Ltd.: London, UK, 2021; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A.K.C.; Wong, F.K.Y.; Ngai, J.S.C.; Hung, S.Y.K.; Li, W.C. Effectiveness of a Health-Social Partnership Program For Discharged Non-Frail Older Adults: A Pilot Study; BioMed Central Ltd.: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ohinata, A.; Picchio, M. The Financial Support for Long-Term Elderly Care and Household Saving Behaviour; GLO Discussion Paper, No. 43; Global Labor Organisation (GLO): Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gospel, H.; Nishikawa, M.; Goldmann, M. Varieties of Training, Qualifications and Skills in Long-Term Care: A German, Japanese and UK Comparison; SKOPE research paper, no. 104; ESRC Centre on Skills, Knowledge and Organizational Performance (SKOPE): Cardiff, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, S.; Tsuru, S.; Iizuka, Y. Models for Designing Long-Term Care Service Plans and Care Programs for Older People. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2013, 2013, 630239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Williamson, C. Policy Mapping on Ageing in Asia and the Pacific Analytical Report. HelpAge International East Asia/Pacific Regional Office, Thailand. 2015. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/55c9e6664.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Review of Initiatives on Long-Term Care for Older People in the Member States of the South-East Asia Region; World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia: New Delhi, India, 2019.

- Gunn, K.M.; Luker, J.; Ramanathan, R.; Ross, X.S.; Hutchinson, A.; Huynh, E.; Olver, I. Choosing and Managing Aged Care Services from Afar: What Matters to Australian Long-Distance Care Givers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koris, R.; Nor, N.M.; Haron, S.A.; Hamid, T.A.; Aljunid, S.M.; Nur, A.M.; Ismail, N.W.; Shafie, A.A.; Yusuff, S.; Maimaiti, N. The Cost of Healthcare among Malaysian Community-Dwelling Elderly. J. Èkon. Malays. 2019, 53, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, J.; Zheng, M. Green Governance: New Perspective from Open Innovation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of Green HRM Practices on Employee Workplace Green Behavior: The Role of Psychological Green Climate and Employee Green Values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Qadeer, F.; Mahmood, F.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H. Ethical Leadership and Employee Green Behavior: A Multilevel Moderated Mediation Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Artz, B.; Davis, D.B. Green Care: A Review of the Benefits and Potential of Animal-Assisted Care Farming Globally and in Rural America. Animals 2017, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- de Boer, B.; Hamers, J.P.; Zwakhalen, S.M.; Tan, F.E.; Beerens, H.C.; Verbeek, H. Green Care Farms as Innovative Nursing Homes, Promoting Activities and Social Interaction for People With Dementia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Determinants |

|---|---|

| Population | Older adults (50–59 years old) and elderly (6o years and above) in Asia. Elderly OR elderly persons OR older adults OR ageing OR senior citizens OR old persons OR aged |

| Intervention | Received or provides social or health care for any form of needs for the elderly. Formal or informal care, integrated care, continuum care, transitional care, rehabilitation care, nursing, and mobilization care. |

| Comparator | None |

| outcomes | Finance model, human resources, model of long-term care (LTC.) |

| Database | Search String |

|---|---|

| PubMed | Carers OR caregivers OR parental duties OR filial piety OR formal OR informal AND integrated care OR continuum care OR transitional care OR Asia. Filters applied:free full text, associated data, comparative study, meta analysis, review, systematic review, in the last 5 years, human, english, malay, MEDLINE, aged 60+ years |

| Sage Journal | Needs OR gerontology OR geriatric OR welfare OR support OR nursing OR community service OR aid OR rehabilitation AND integrated care OR continuum care OR transitional care AND Asia Filters applied: [[Abstract needs] OR [Abstract gerontology] OR [Abstract geriatric] OR [Abstract welfare] OR [Abstract support] OR [Abstract nursing] OR [Abstract community]] AND [[Abstract service] OR [Abstract aid] OR [[Abstract rehabilitation] AND [Abstract integrated]]] AND [[Abstract care] OR [Abstract continuum]] AND [[Abstract care] OR [Abstract transitional]] AND [Abstract care] AND [Abstract asia] |

| Advance Google Scholar | Elderly OR older adults OR ageing OR senior AND social care AND health care AND integrated care AND continuum care OR transitional care AND Asia AND Barrier AND long term care Filters applied:Elderly OR older adults OR ageing OR senior AND social care AND health care AND integrated care AND continuum care OR transitional care AND Asia AND Barrier AND long term care |

| Springer | Social care service OR aged community-based OR elderly support service OR elderly social work OR old age assistance OR elderly casework AND integrated care OR continuum care OR transitional care Filters applied:’Social care service OR aged community-based OR elderly support service OR elderly social work OR old age assistance OR elderly casework AND integrated care OR continuum care OR transitional care within English, Article |

| Item | Inclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Date of a published article | 1 January 2015 to April 2021 |

| Exposure of interest | Social care model for elderly Healthcare model for elderly |

| The geographical location of the study | Asia |

| language | Malay and English |

| participants | Older adults (50–59 years old) and elderly (60 years and above) |

| Reported outcomes of interest | Finance model, human resources, model of long-term care (LTC.) |

| Study design | Systematic review, quantitative, qualitative and mixed-method study |

| Reference | Country | Region (Study Location) | Objective | Study Design | Sample Population | Elements | Study Output | Risk of Bias | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finance Model | Human Resources | Model of LTC. | ||||||||

| Briggs et al., 2018 [19] | Australia, Belgium, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Scotland, Singapore, Spain, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, UK, USA. |

|

| Review of reviews Period: 2015–2017 |

| Mortality; hospitalization; cost and resource utilization; physical functioning; psychological functioning | Various publicly and privately funded models | Nurses, physiotherapists, general practitioners, and social workers | Community services which may include the non-government and unpaid sectors | +++ |

| Chavez, Dwyer & Ramelet 2018 [20] | Canada, Netherlands, Taiwan, USA. |

|

| Scoping review Period: January 1980 and March 2016 |

|

|

|

| Primary care, home care, long-term care, acute care, and transitional care | +++ |

| Kirst et al., 2017 [21] | Australia, Canada, France, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, U.S.A., UK, |

|

| Realist review Period: January 1980 and July 2015 |

|

|

|

|

| +++ |

| Stoop et al., 2019 [22] | Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, USA. |

|

| Scoping review Period: 2006–2018. |

|

| Not available | General practitioners, social workers, elderly welfare consultants, physical therapists, occupational therapists, dietitians, pharmacists, (specialist) nurses, psychologists, geriatricians, nursing home physicians, psychiatrists, and other medical specialists. Involvement of r community organizations providing services beyond the (professional) expertise of the core | Home care needs to assess frailty or complex/multiple health and social care needs in various domains of life, which may benefit from an integrated care approach. The program needs to enhance professionals and students’ skills, efficient care, and quality of life. | +++ |

| Threapleton et al., 2017 [23] | Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, UK, USA. |

|

| Scoping review Period: 2005 to February 2017 |

|

| Funding should be realigned, pooled, and ring-fenced to facilitate the integration of services. | Case managers, nurses, or social workers | Integrated care consists of 8 components: (i) care continuity/transitions; (ii) enabling policies/governance; (iii) shared values/goals; (iv) person-centered care; (v) multi-/inter-disciplinary services; (vi) effective communication; (vii) case management; (viii) needs assessments for care and discharge planning | +++ |

| Song, P. & Tang, W. 2019 [24] | Japan |

|

| Cross-sectional study |

|

| Not available | Nurse specialists | Community-based (e.g., provides a variety of homes), Institutional services (e.g., strictly on physical and mental status) | +++ |

| Du, P. & Wang, Y. 2016 [25] | China |

|

| Policy review |

|

| Not mentioned | Emphasis on eldercare providers within families as a foundation, the community as the base and governments/agencies as supplementary | Conceptualize ‘integrated care’ and ‘new healthy ageing’ as ‘elderly care road with Chinese features’. Encouraging social participation in the cultural foundation for elderly care. Proposing reconstruction and consolidation of elder family care capabilities to support elder care capacities of the families through social services, the development of long-term care insurance systems and relevant service systems, and narrowing the gap amongst various areas of service provision | ++ |

| Cassum, Cash, Qidwai & Vertejee 2020 [26] | Pakistan |

|

| Qualitative exploratory study |

|

| The religious community provide the funding based on an assessment by SWB (Social Welfare Board), lack of family support | Nurses, physiotherapists. Capacity building training to HCPs for the care of the elderly | Shelter homes need a policy on retirement Socio-cultural value related. | +++ |

| Sun et al., 2021 [27] | Canada, Hong Kong, Philippines, Republic of Slovenia, Switzerland, UK, USA. |

|

| Meta-synthesis Period: from their inception until April 2020 |

|

| Not mentioned | Nurses caregivers involved in the decision-making process | Nursing care, assisted living, residential care, and long-term care, transition to residential care facilities, cultural adaptation | +++ |

| Lawless, Marshall, Mittinty & Harvey 2020 [28] | Australia, Canada, Denmark, Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, UK, USA. |

|

| Scoping review Period: June 2008 to July 2019 |

|

| Not mentioned | Various healthcare settings, including primary care, hospitals, allied health practices and emergency departments, ‘good’ patient-provider communication and relationships, open communication and sharing Decision-making, perceptions of safety and care quality. | Integrated (coordinated) Healthcare. Need to have continuity, both in terms of care relationships and management, seamless transitions between care services and/or settings, and coordinated care that delivers quick access, effective treatment, self-care support, respect for patient preferences, and involves carers and families. | +++ |

| Noda et al., 2021 [29] | China, Indonesia, Japan, Philippines, Thailand, South Korea |

|

| Cross-country study using document review and informat interview on policy, strategy and regulation of care provision |

|

| Not mentioned | Strengthening Doctor and hospital-based healthcare delivery system, livelihood support coordinator, | Healthcare service delivery policies, the transformation of service delivery system., long term care and welfare. National commission on social security reform, home care model, community services centre, integrated care, | +++ |

| Wong et al., 2020 [30] | Hong Kong |

|

| single-blind randomized controlled trial and follow up observation. |

|

| Departmental research fund of the Hong King Polytechnic University | Advance practise nurse and nurse case manager | Health-social partnership program | ++++ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alavi, K.; Sutan, R.; Shahar, S.; Manaf, M.R.A.; Jaafar, M.H.; Abdul Maulud, K.N.; Embong, Z.; Keliwon, K.B.; Markom, R. Connecting the Dots between Social Care and Healthcare for the Sustainability Development of Older Adult in Asia: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052573

Alavi K, Sutan R, Shahar S, Manaf MRA, Jaafar MH, Abdul Maulud KN, Embong Z, Keliwon KB, Markom R. Connecting the Dots between Social Care and Healthcare for the Sustainability Development of Older Adult in Asia: A Scoping Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052573

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlavi, Khadijah, Rosnah Sutan, Suzana Shahar, Mohd Rizal Abdul Manaf, Mohd Hasni Jaafar, Khairul Nizam Abdul Maulud, Zaini Embong, Kamarul Baraini Keliwon, and Ruzian Markom. 2022. "Connecting the Dots between Social Care and Healthcare for the Sustainability Development of Older Adult in Asia: A Scoping Review" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052573