1. Introduction

Urban spaces should be designed to reflect sustainable communities for the independent functioning of older adults. Sustainable communities imply functional urban spaces in which older people can meet their living needs through ease of mobility and adequate design, which should result in residential satisfaction.

Understanding the needs of the older adult population is important for achieving a good quality of life and forming sustainable communities. Appropriate housing and quality design of public spaces reduce risks to the health of older adults. The conditions for reducing social and health costs are provided through independence and prosperity [

1]. According to several authors, wellbeing is used to define social sustainability [

2]. It also requires sustainable mobility in the context of the needs of the older adult population. This can be achieved through infrastructure improvements and accessibility [

3].

Physical changes in the neighborhoods inhabited by older people affect their quality of and way of life, as well as their satisfaction with the built environment, because these changes are mostly associated with the locations in which they live. This association refers to buildings, areas and services in their vicinity. Satisfying the needs, trends and activities of older adults is generally reduced to just their place of residence while their mobility is reduced with age [

4,

5]. Urban transformation and revitalization change the built environment, and in the process, they affect the activities of older adults; they perceive changes in the area as a negative or stressful experience, which significantly affects the quality and the way of their lives [

6]. There are also positive effects from these changes, related to the quality of housing and the enhancement of accessibility to daily facilities [

7]. The residential satisfaction of older people is one of the indicators of eligibility for residential communities, and a number of studies have been written on this subject [

4,

8].

Related studies emphasize the disadvantages of this process in Western cities: the loss of affordable and cheap shops and affordable housing, impersonality and privatization of public spaces, and community deterioration [

9,

10,

11,

12]. The processes of transformation and revitalization of the post-socialist cities of Eastern Europe (CEE) also have a negative impact on the quality of life of the local population, by which older people are particularly affected [

13]. Despite the lack of empirical research dedicated to the quality of life and satisfaction of older people in relation to their residential environment in CEE, the latest research shows that these changes garner positive reactions in some cities [

7].

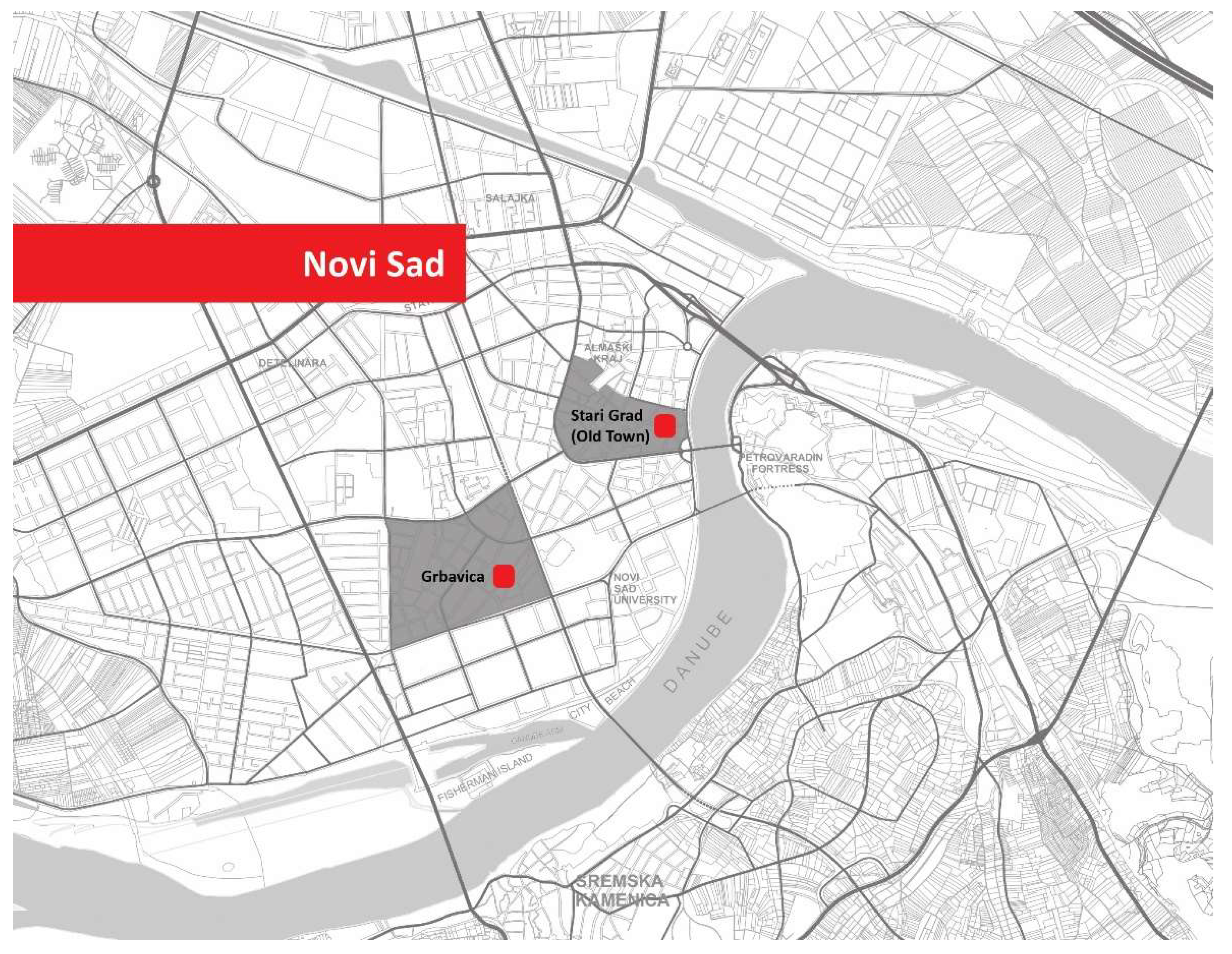

The aim of this paper is to examine the residential satisfaction of older adults, through the conditions of mobility and the quality of the public spaces in which this mobility takes place, using examples of transformed urban areas of Novi Sad. Serbia is a European country that is not an EU member but is in the process of association; this is the first study carried out in such a country, which extends its importance beyond that of a case study. This approach differs from the existing urban studies dealing with residential satisfaction. In previous studies, research on the residential satisfaction of older adults has been conducted at the level of accessibility of facilities, security in the urban environment, and interaction with the environment. This research benefits, in part, from the experience of these surveys, but largely examines the residential satisfaction of older adults in terms of mobility, namely their ability to move using facilities offered by public transportation and public places. This paper examines residential satisfaction in parallel with the analysis of the functionality of space, the orderliness of public areas, the possibility of movement in space, and accessibility to public transport. Traffic problems are evident in Novi Sad; therefore, these aspects are of great importance for the quality of life and residential satisfaction of people whose mobility is impaired or limited.

Since the mobility of older adults is one of the preconditions for their independence and for the quality of their daily (sustainable) life, it is very important to examine whether public transport is suited to their needs, which could significantly affect the results of the survey as an indicator of residential satisfaction. Furthermore, it is considered that the arrangement and adjustment of public spaces to the mobility needs of older people is extremely important in terms of their mobility and freedom in space.

Social, political and economic changes have generated processes for the transformation of cities in post-socialist countries since the beginning of the 1990s. These changes are related to the physical structure of the city, its facilities and its functions, as well as the city landscape [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Some places are more intensely affected by these changes, especially the central areas of large cities that are social, administrative and economic centers. Cities in different countries have regenerated differently, depending on the political stability, the development of institutions, economic development and the development of urban policy [

19].

The quality of the built environment depends on numerous factors (these may be of a social, housing, economic, financial, health, urban or spatial nature), as well as on personal characteristics and each person’s life. The residential mobility behavior of neighborhood residents can also be influenced by their impression of other city residents in their neighborhood, in other words, the perceived reputation of the neighborhood [

20]. One of the criteria for evaluating quality of life in sustainable communities could be residential satisfaction. In a referenced study, it is stated that: “It is one of the ways to evaluate the quality of urban environment, usually by neighborhood residents” [

7]. Older people’s residential satisfaction is discussed within the context of an age-appropriate living environment [

4,

8] and the everyday effects of urban revitalization [

9,

10,

21]. Good access to green spaces in an urban environment, from an urban-planning perspective, has positive health impacts on older populations [

22]. Green infrastructure provides environmental services in urban areas, which are a prerequisite for ensuring biodiversity, social and territorial cohesion, sustainable development, and overall human wellbeing [

23].

In the global field of built-environment studies, results indicate that the community type and the characteristics of the dwelling unit are two very important factors of residential satisfaction [

24], as well as home ownership [

25]. The older adults were therefore viewed as a negative part of the population through their dependency, impoverishment and decline of their mental and physical health. However, it was observed that older people tend to come to terms with the reality of their environment and adapt to it [

4]. Social activities, relationships and trust positively influence the increase in residential satisfaction of older people, as well as the availability of professionals that can assist them in case of need, which has been confirmed through studies [

8,

26,

27]. The sense of safety and security in the community contributes to a more independent life and increases mobility and opportunities for socialization. The term “mobility” is often used with different meanings, depending on the context. Speaking of older adults, the most important definition of mobility is crossing small distances, from the place of residence to the retail or service facilities that are frequently used [

5]. Public spaces are greatly shaped in the process of urban planning, and both are very important for senior citizens’ mobility.

In some studies, it was shown that the frequency of using public transport, in relation to other means of transport, is the highest for crossing greater distances or leaving the immediate area (from 2 to 5 km away) [

4]. This refers to the movement for the purpose of leisure: “…the majority of older population in high-density urban developments, which are characterized as having high quality public transit connections, prefer to use public transit…” [

4]. The older population, especially above the age of 75, is dependent on public transport. However, most find it difficult to use, as they need to walk to the bus stop to board, and in addition, public transport cannot ideally cover all areas [

28]. On the other hand, older adults today use cars more often than their predecessors due to the greater availability of cars and the higher share of drivers in the population. Driving as a driver or co-driver is quite popular [

29]. However, low-density development, especially in the USA, is connected to the locational flexibility of automobile and the associated road network, thus unfavorably affecting human health, social welfare, and ecological conditions [

28]. Such adverse effects can strongly influence the residential satisfaction, especially of older adults, in cases where their place of residence is a result of urban sprawl.

In Western Europe, the US and Australia, there is a growing trend among the older population to increasingly use cars as primary means of transport. However, recent studies in Asian cities suggest that in order to increase public transport usage (and therefore lower car-ownership) it is crucial to enable high accessibility to local daily opportunities (i.e., local provision of retail and service facilities) [

30].

The process of urban revitalization mainly occurs due to economic, social and political changes in a country, and it involves making changes to the entire system of urban planning. Economic aspects of neighborhood revitalization are strongly indicated since the financial and utility value of an area follows its growth. The commercialization of facilities and the privatization of an area, as well as the need to maximize the profit, all effect the neighborhoods and negatively affect the lives of residents. There are also positive effects of this process, such as better housing quality and accessibility to local retail stores that have more competitive prices [

7,

31]. This often leads to loss of residence or relocation due to the inability to adapt to new conditions and housing prices. This phenomenon is part of the gentrification process which occurs as a result of urban revitalization, and it has been the subject of a number of studies [

9,

21,

32]. In such circumstances, high-quality public transport suitable for the needs of the older adults can significantly facilitate their housing situation by enabling them to easily access the necessary facilities and certain public spaces. New housing developments stimulate the introduction of new public transport lines and new public transport systems, which contributes to space networking, creates dynamic mobility, and stimulates the use of public transport [

33].

The literature has shown that the emergence of new commercial facilities, wealthier residents and consumers generates numerous transformations in neighborhoods, which is reflected in the rise of land, real estate and rents prices, reconstructions and upgrades, land-use change, as well as modifications of the social structure of the neighborhood and the landscape layout [

9,

34,

35]. Most authors state that these changes, typical for the revitalization process in post-socialist cities, satisfy one part of the population, while for others, this implies deterioration of the social and housing situation [

9,

11,

21,

36]. In these studies, such changes of the neighborhood have a negative impact on its original residents who are exposed to the pressure of a different living environment to which they should adapt. The latest research shows that these changes have positive reactions in some of CEE [

7]. In political terms, the displacement becomes one of the urban strategies which governments of developed countries encourage by implementing urban revitalization projects [

9,

37]. This is the method by which some of the community’s problems, such as outdated infrastructure and evident poverty, are being solved. This also represents additional pressure on the local population in neighborhoods exposed to revitalization.

In neighborhoods where the necessary facilities are not easily accessible and the access to walking and cycling areas is limited, efficient and reliable public transport suited to the needs of the older adults will contribute to their independence, which is highlighted in the existing literature [

4,

5] and will be further analyzed in this study. In the case of restricted opportunities for walking or cycling, the availability of public transport is a prerequisite for ensuring that older adults can have an independent life. If public transport is suited to the needs of older people, they tend to use it more often [

38]. Vehicles adapted for people with mobility impairments, adjusted schedule and additional services provided during transport represent good public transport for older adults. This study will examine the possibilities and usage conditions of public transport. It has been observed that the mobility is perhaps the most important factor of residential satisfaction.

In order to move freely within a neighborhood, pedestrian routes, safe sidewalks and entryways, denivelation, and crossing barriers for people with disabilities are very important for the older adults. Free and adequate movement implies the provision of appropriate urban furniture. The quality and functionality of the space depends on the existence of places for rest and socialization, their visibility, and positioning in relation to the directions of movement and accessibility. Walking contributes to older adults’ agility and the establishment of social interactions. In the process of urban revitalization, the provision of surfaces for all modes of transport and their appropriate adaptation for use, especially for the older adults, occupies an important place.

Novi Sad had a long period of socialist life. Prior to that, it was fairly adequately organized within the two monarchies, given the small demands of the smaller town and adequate planning from the Austro-Hungarian period. The socialist period brought long-term development, emphasized the use of cars, the creation of large boulevards, and mass introduction of bicycle paths in all major streets of the city. However, at the smaller scale, accessibility, sizing and arranging of areas for movement of people with special needs and older adults has not been adequately addressed. This continued in the post-socialist war period and later transition period, where unregulated urbanism prevailed. Consequently, there was no room left for humanistic and welfare principles in shaping the public space, which was reflected in the two analyzed neighborhoods. Conditions for the movement and stay of people in public spaces are especially difficult for the older population. Urban transformations, resulting from urban planning principles of Serbian transitioning capitalism, have neglected the needs of older adults.

The paper consists of five parts. In the Introduction, the research problem, aim and current literature is presented. The second part describes the methodology applied in order to collect data in two revitalized neighborhoods of Novi Sad on samples of adults aged 60 years or over. The third part is the case study of the Old Town and Grbavica neighborhoods. Data processing and research results on residential satisfaction of older adults are presented in the fourth part of the paper through two sections. The first presents the results of a survey of residential satisfaction of older people through the analysis of the availability of content, security in the neighborhood and the community interaction. The second segment presents the results of the research of residential satisfaction of older people through the analysis of the trends and conditions of movement within the public space of the mentioned revitalized urban neighborhoods. The fifth part of the paper is the conclusion on residential satisfaction of older people in the analyzed neighborhoods, based on the obtained results.

5. Conclusions

Social changes in Eastern European countries which have gone through the process of post-socialist transition have led to significant urban change in larger cities, meaning their rehabilitation and reconstruction. This has greatly affected the quality of and way of life of their inhabitants, among which some groups, such as people aged over 60, have been more affected by these changes. The particularities of the post-socialist changes, their context, timing and results on the urban planning level are influencing the creation of new, different urban environments, which can offer good quality-of-life conditions to older people, allowing them freedom of movement, access to numerous facilities and a social environment that meets their requirements. However, factors such as income levels, psycho-physical conditions or subjective expectations can also affect the quality of life of older people in this region of post-socialist communities. As such, this research aimed to examine the residential satisfaction of older adults in Serbia.

The older population positively experiences changes in neighborhoods relating to the availability of facilities and security. It has been confirmed that touristification and commercialization of facilities in the Old Town of Novi Sad cause higher prices in retail stores and increase in the number of foreigners, which affects the slightly lower degree of satisfaction compared to Grbavica. The construction of several large supermarkets and a number of smaller ones in Grbavica has caused lower product prices, which benefits older adults. However, older people do not positively experience the change of social structures in the process of gentrification, in the sense of neighborhood support and willingness to communicate. The satisfaction of older people with the arrangement of pedestrian routes, availability of places for relaxation and their adaptation to population of the persons of 60 and lower is rather low. They perceive public spaces as unkempt and unmaintained and maladjusted to their needs during walking, which is the most common form of movement. Grbavica is being seen more positively in comparison to the Old Town, especially with its availability of relaxation spaces, which is the only aspect that more than 50% of respondents found positive. This can be attributed to the existence of several smaller park areas within the neighborhood, which older adults prefer over larger parks. Public spaces in the Old Town are being occupied by various visitors, tourists and other groups, making older people feel insecure and peace-deprived. Public spaces are thus arranged in a way in which they do not provide older people with adequate mobility, which is one of the most important aspects of residential satisfaction. At the same time, public transport represents an alternative which the older people choose only when traveling longer distances, while cars and bicycles are rarely used. It is also evident that using public transport is more common among older adults living in the Old Town, where the conditions for the use and parking of cars are very poor, while Grbavica offers better conditions for their participation in traffic.

The research results show consistency with other recent studies, because older people positively experience the availability of affordable shopping and service infrastructure. The results confirm that the effects of urban revitalization also have a positive spectrum. However, generally, urban revitalization in the context of a post-socialist and post-transitional city such as Novi Sad does not consider the needs of older people, on a level of efficiency of public transport and quality of public spaces, which is a wider problem. The process and system of the city revitalization as well as its construction do not acknowledge the needs of older people on the level of urban planning and arrangement of public spaces. In these circumstances, it can be concluded that public spaces do not contribute to the mobility of older people and, therefore, their residential satisfaction.

Limitations of this study arise from the material status of a certain part of older population, which, in addition to those analyzed, also affect mobility, the choice of transportation and availability of facilities and shops. Moreover, only the “healthy sample” was recruited because those with limited physical mobility remain indoors and at home, and problems within the neighborhood area are of secondary importance to them. In future works, the attention will be turned to the availability of non-commercial facilities, culture, arts and entertainment for older adults, which can also greatly affect their residential satisfaction. The city administration’s policymaking could make these facilities more available and adjusted to older people, allowing them easier access, for example, by introducing specific lines of public transport. The process of revitalization in these two neighborhoods in Novi Sad did not respond in the best way to the needs of the older adults regarding its urban planning and design of public spaces, relaxation spaces, cycling paths, and by not maintaining these areas properly. This research has shown the need to establish an appropriate relationship, during the urban revitalization and transformation, between the needs of commercialization of urban space and the needs of older adults. Therefore, the content that causes high traffic, crowds and intense activities should not disturb the peace, privacy and leisure needs of older adults in public spaces. Furthermore, it was shown that the pedestrian infrastructure in all parts of the neighborhood should be fully adapted to the movement of older people, removing all obstacles to movement and adequately dimensioning and allocating it. Urban revitalization influences the everyday lives of the older residents in the city center and push for adaptations of their daily routines and habits in the “new town”. The responsibility of local authorities and urban planners dictates to pay more attention to older people’s needs when planning and designing public areas, to provide better conditions for their active life and to create inclusive cities and more sustainable communities across post-socialist Europe. Environments should be created to suit the needs of all age groups on the level of spatial planning of a post-socialist city.

Older people responded very clearly to the survey and expressed residential dissatisfaction with the issue of mobility in a transformed urban environment. Future surveys of residential satisfaction should contain questions on the topic of mobility, as they provide clearer insight into reasons of (dis)satisfaction. The questions could be adapted to some local peculiarities of the analyzed cities, extended beyond the limits of this study, concerning the material status of the respondents and the physical and health limitations of the older adults. The results obtained can serve as an input for key policy guidelines that will lead to a high level of residential satisfaction of older adults in future transformations of urban areas.