1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the century, the renovation of China’s old neighbourhoods has undergone a long period of change, from the “renovation of shanty towns” of the past, to the “micro-renewal” of the present, which is the inevitable result of the development of national conditions. Since the third session of the 13th National People’s Congress [

1] on 25 May 2020, which included old neighbourhoods in the construction of the “New infrastructure, new urbanization, transportation, water conservancy and other major projects”, the number of old neighbourhoods renovated from January to October 2020 reached 94.6%, and by November 2020, the number of new renovations started reached 3.97%. By November 2020, the number of old districts newly renovated reached 39,700, exceeding the original target [

2]. In addition, the Government Work Report for 2021 proposes to start renovating up to 53,000 new old urban districts [

3]. In China, the renovation of old neighbourhoods is in full swing. However, in the process of renovation, there are still many problems faced. In addition to the deficiencies in the infrastructure of the old neighbourhoods themselves, more often than not, the failure to fully understand the renovation needs and living experience of the occupants before renovation has resulted in the pursuit of renovation quantity at the expense of renovation quality [

4], making it difficult to achieve sustainable renovation. Based on the current context, this paper conducts interviews with residents of old neighbourhoods, conducts research from the perspective of living experience, and proposes sustainable renewal strategies for old neighbourhoods.

2. Theoretical Framework

There are similarities between community regeneration in different countries, with Stephen Hall finding similar approaches in the UK and France around 2010 Specifically analysing the similarities and differences between the two countries [

5], Van der Pennen uses empirical examples from the Netherlands and the UK to show that the role of practitioners should be emphasised in community regeneration [

6].

Scholar Wan JiunTin points out through his research that directing community renewal towards “social interaction” is more conducive to sustainable community renewal, thus improving the quality of life [

7], motivating different stakeholders, and also enabling “top-down” redevelopment [

8]. It is shown in scholar Fred Robinson’s research, however, that unrestricted involvement of residents in community renewal is not desirable [

9]. After analysing the causes of decline in deprived communities in the UK, scholar Wallace M. also found through his research that the focus in community renewal is on public services, and that partnerships can be established locally that focus on community needs [

10].

In Europe, community renewal has been developed as a model of urban governance, but after scholar Aalbers, M. B. studied community renewal in physical, economic, and social terms, there was an imbalance found between policies that focus on physical foreboding and those that focus on social intervention [

11]. Many deprived areas have seen significant improvements in their living environment following neighbourhood renewal, but the lack of a mechanism to regulate neighbourhood equality has made it difficult to close the gap with other areas [

12].

Siqiang Wang developed a conceptual framework to understand older people’s right to the city in older neighbourhoods, and narrowed the scope of the right to the city study to rights to community facilities. Using three communities in Kwun Tong, Hong Kong as his case study, the study found that the density of facilities was not equitable between high and low economic level in communities, so it was important to ensure that older people living in low-economic-level communities had the same rights to use community facilities, extending the information on using mobility to increase older people’s right to the city, and also providing reference suggestions for future planning of age-friendly communities [

13].

A search of the CNKI database revealed a total of 3140 research journals related to old neighbourhoods and 80 research journals related to living experience. The overall trend graph of the number of articles published shows that the attention to research related to old neighbourhoods has been increasing year by year, especially in recent years, and has become a hot spot of social concern.

In order to find a breakthrough in the study, the author conducted a search of the CNKI database, analysing the search term “old district renovation” and controlling the results in the last five years (2017–2021), initially obtaining 166 articles, and then manually sifting out articles unrelated to old district renovation before finally obtaining 99 valid articles. The selected articles were analysed by CiteSpace, and the keyword co-occurrence graph (

Figure 1) and timeline clustering graph (

Figure 2) were derived to analyse the research related to old neighbourhoods in the past five years. For example, certain scholars [

14] divided the existing renovation content into three segments: respectively architectural restoration, public environment creation, neighbourhood atmosphere reshaping, and proposed countermeasures for the renovation of each of the three segments. These emphasise that the renovation needs to be systematically designed, overall pushing the main body into repair, and distributed implementation. Scholar Wang Zhenpo [

15] analysed the attributes of China’s old neighbourhoods and the characteristics of upgrading renovation. Additionally, the renovation process by some scholars [

16,

17] takes the problem of financial pressure in renovation as a starting point, and proposes to promote the renovation process through the intervention of external forces and the improvement of renovation methods and governance systems.

The living environment experience has long been discussed by scholars in explaining the choice of living environment, but previously, it was often used to explain the choice of living environment, and early discussions of the living experience only stayed at the level of environmental experience [

18].

Rosemary Kennedy has since predicted that the share of multi-storey apartment buildings in the housing stock of subtropical cities will increase dramatically in the coming decades [

19], and has then explored the issue of livability and experience of multi-storey flat houses in subtropical cities, with the hope of reducing energy consumption at the same time. Kennedy finally found that natural ventilation and the availability of outdoor private living space play an important role in livability in the region. In terms of safeguarding the residential experience of residents, the premise is that it can also reduce energy consumption.

In 2016, the use and emotional experience of the living environment was again shown to have a significant impact on satisfaction with living [

20], and it was detailed that the size of the home, the type of housing, marriage, and children all have different levels of impact on satisfaction with living.

At the same time, the heat island effect has become a serious social problem in Korea and has seriously affected the living experience of Korean metropolitan residents. Studies have found that residents are willing to reduce the heat island effect by increasing the area of green areas (including trees in living areas, trees in street areas, parks in residential areas, trees in school areas, etc.). There is a marginal willingness of residents to pay

$56.68–

$76.59 for each additional m

2 of urban greenery [

21].

A study has also been carried out on traditional houses within the Nicosia City walls (houses that have mostly lost their function as dwellings), using a user experience assessment remould, in which the socio-cultural continuity of preserving old buildings is emphasised through literature surveys, field research, and questionnaire interviews considering three aspects: the socio-cultural, economic, and physical, ultimately concluding that when buildings are adapted for commercial, cultural, and educational use, they better contribute to the socio-cultural continuity and economic development of the city, as well as to its living experience [

22].

Siyi An has studied settlement behaviour in shrinking areas, establishing an RMD framework through subjective, environmental evaluation dimensions, mental dimensions, and cognitive dimensions, and conducting questionnaires in different communities in Japan. The findings were that residents of suburban communities tend to consider overall satisfaction with their location when considering settlement, while residents of mountainous communities place more emphasis on emotional satisfaction factors, with the results suggesting that area design that enriches residential experience and neighbourhood communication is important in promoting population settlement [

23].

Zdravko Trivic conducted a multisensory assessment of older people in a high-density residential area and found that the sensory richness of the community influences the daily behaviour of older residents and ultimately residential well-being, and that the findings provide sufficient information to support the redesign of the community [

24].

Based on the existing research results of old neighbourhood renovation studies, an attempt is made to explore and analyse the actual living experience of the residents in old neighbourhoods with the renovation audience as the focus, and to propose sustainable renewal strategies. Similarly, Guangzhou City insisted on promoting the renovation of old neighbourhoods, and in 2020, the city completed 232 micro-renovations of old neighbourhoods [

25], while by 2021, it had completed 787 renovations of old neighbourhoods, renovated 45.06 million square metres of old floor space, installed 96.2 km of additional barrier-free access, and added 618 new pocket parks and community public spaces [

26]. In the future, Guangzhou will also promote a comprehensive mass participation mechanism and improve the social governance system, gradually moving from “having a place to live” to “having a good place to live” [

27]. The Yuexiu District of Guangzhou is an old urban area with a large number of old neighbourhoods, and the study is representative of this area. The results of the study, if validated, can be replicated in Guangzhou and across the country.

3. Methodology

Through field research, resident visits, and expert interviews, high-frequency words were extracted for attribute categorization; indicators at all levels for measuring living experience were identified; a framework for measuring residents’ living experience was built [

28]; and the three-level indicators in the framework were used as the core questions. Questionnaires were designed through the relationships between the indicators, 32 people were selected for a small sample test, and the test results were examined to generate the final questionnaire, which was generated after testing the test results. The questionnaire data were collected and integrated to determine the attribute categories of each tertiary indicator in the Kano model, calculate the better value (satisfaction coefficient after increase) and worse value (dissatisfaction coefficient after elimination) of each tertiary indicator, and finally, to place each indicator in a four-quadrant diagram to give specific update strategies on top of the living experience perspective.

3.1. Preliminary Research and Framework Building

First of all, through the field survey (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), to build a field research map (

Figure 7), combined with the residents’ interviews, we learned that the specific renovation projects of the old district mainly include: car park expansion, lift retrofitting, firefighting improvement, facade improvement, property improvement, district entrance image enhancement, construction of elderly care facilities, electrical circuit renovation, water pipe renovation, optical cable laying, community service station retrofitting, illegal construction regulation, and overhead line rectification, etc.

Secondly, the content of the resident interviews was categorised into functional and environmental attributes, and each of the three levels of the measurement model were identified (

Table 1).

3.2. Model Building

This study uses the Kano model theory [

29]. The Kano model is always used in the pre-development stage of product design to determine the demand attributes of each design point, prioritise them, and make design recommendations [

30]. The Kano model can also be applied to other fields, for example, the scholar Dace uses the Kano model to assess the quality of the environment [

31]. It is also used in the field of eco-city user requirements development [

32]. The two-dimensional model and the two-factor theory of the Kano theory can also be applied to the spatial environment as a more dimensional “product”, with the degree of transformation as the horizontal axis and the satisfaction of living experience as the vertical axis. Undifferentiated, desired, and inverse attributes calculate the better and worse values of each tertiary indicator, absolute the worse value, place each tertiary indicator in a four-quadrant diagram, and prioritise the renewal items [

33].

The Kano evaluation table is the standard for rating the final attribute categorisation of each level three indicator and the Kano evaluation table (shown in

Table 2).

In this paper, the meaning of the various categories of requirements in this table are specifically referred to as follows.

M: Basic needs. When this indicator is low and the needs of the occupants are not met, the occupants’ living experiences are very poor, while when this indicator is high and the needs of the occupants are met, the occupants’ living experiences are good.

O: Desired demand. When this indicator is low, the occupants’ living experiences are very poor, whereas if it is retrofitted to a high degree, the occupants’ living experiences are greatly enhanced.

A: Attractive needs. When these indicators are low, the living experience of the occupants may not be affected too much, while when they are high, the living experience of the occupants will be greatly enhanced.

I: Non-differentiated demand. Whether the indicators are available to a high or low degree, they do not cause much fluctuation in the occupants’ living experience.

Q: Doubtful demand. When the level of the indicator is high or low, the occupant indicates either that they like this or that it is unacceptable.

R: Reverse demand. When this indicator is low, the occupants’ living experiences are high, and when it is high, the living experiences are low.

3.3. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire was divided into two parts. The first part was basic information, namely gender, age, and occupation; the second part was core questions, setting positive and negative questions (shown in

Table 3) for each tertiary indicator to facilitate subsequent attribute categorisation of each indicator [

34].

3.4. Questionnaire Distribution

This questionnaire distribution selected some old communities in Yuexiu District, Guangzhou City, and the objects were residents of the Ouzhuang Interchange Community, Ouzhuang Community, East Huanshi Road Courtyard, and Donghuan Road Courtyard (

Figure 8). The questionnaire was distributed online and offline, and the questionnaire was distributed between 23 December 2021 and 10 January 2022.

Offline questionnaires were distributed between 9:00 and 10:00 a.m., and 17:00 and 19:00 p.m., during the peak period of residents’ shopping for vegetables and returning home from work, in which there are many residents who go out. Interviewees went to the selected residential areas, which randomly selected residents and issued questionnaires. However, the average age of residents in this area is older, and some middle-aged and elderly people had difficulty understanding the content of the questionnaire quickly. The interviewees explained the content of the questionnaire and assisted them in filling in the answers. Online, questionnaires were distributed to owners in selected communities to ensure the authenticity and validity of questionnaire data while ensuring the sample size of the questionnaire.

A total of 230 questionnaires were distributed online and offline, and 216 were recovered, including 93 online and 101 offline. After 12 invalid questionnaires were removed, 204 valid questionnaires were recovered, with a questionnaire recovery rate of 88.7%.

4. Result

4.1. Data Processing

In this questionnaire, there were 96 males and 108 females, and the age range was mainly 35 to 45 years old; with the increase and decrease of this age group, the proportion of the population keeps decreasing. In terms of occupation, public institutions, civil servants, and government workers are the main ones, accounting for half of the total, while professionals, company employees, students, and housewives also account for a certain proportion (

Figure 9).

The data from the online and offline questionnaires were collected and collated, and the tertiary indicators in each questionnaire were numbered (1 to 15) (

Figure 10), (detailed data for

Figure 10 in the

Table A1) along with a table of quality attributes for each dimension (

Table 4). The better and worse values of the tertiary and secondary indicators were calculated (

Figure 11), and the formulae were:

It can be seen visually that there are eight transformation items, categorised as expectation type needs (O), accounting for 53.3%; three undifferentiated needs (I), accounting for 20%; and four charm type needs (A), accounting for 26.7%, while there are no reverse-type needs

® or basic needs (M). As shown in

Table 4, internal experience and external experience are both aspirational needs, but there are some differences between them in terms of the better value and worse value. In terms of better value, external experience is higher than internal experience, while in terms of worse value, internal experience is higher than external experience.

The worse values are taken as absolute values and the numbers 1 to 15 are brought into the four-quadrant diagram (

Figure 12). The numbers in the first quadrant are 1, 2, 3, 8, 10, 14, and 15; the number in the third quadrant is 5; and the numbers in the fourth quadrant are 4, 6, 7, 9, 12, and 13.

4.2. Four-Quadrant Chart Analysis

Based on the above four-quadrant diagram, and taking into account the field research, the renewal projects were prioritised into four echelons.

(1) First tier renewal projects

Fire and security improvements, water, electricity, heat and gas improvements, illegal building regulations, and parking extensions. These regeneration projects are categorised as aspirational needs. From the perspective of residents in newer neighbourhoods, these needs are generally classified as basic needs. In older neighbourhoods, however, such needs have long been unmet, and when they are met, residents of older neighbourhoods do not take them for granted in the same way as the former group, but rather, the living experience is significantly enhanced.

(2) Second tier renewal projects

Lift retrofitting, overhead line regulation, and lighting environment improvement. Elevators are generally not installed in old residential areas, while elevator installation and lighting improvement are more important for middle-aged and elderly groups in the old residential areas. Meanwhile, through field research, it is found that residents in the old residential areas generally have a high degree of aversion to overhead lines, which will greatly affect residents’ living experience.

(3) Third tier renewal projects

Improvements to the image of the façade, the image of the entrances and exits of the neighbourhood, and the image of the roads. In other words, when these three types of needs are not met, they do not significantly affect the living experience of the residents, but when the improvement is completed and the needs are met, the living experience will be significantly improved.

(4) Fourth tier renewal project

Elderly facility additions, electric bicycle and car charging facility additions, fitness facility additions, community service station additions, and green area improvements. The combined better and worse scores for these five renovation projects are the lowest overall, and such facility additions, including the need for green space, do not show large fluctuations in the living experience, regardless of whether they are met to a high or low degree.

The table of quality attributes for each dimension shows that the worse value for internal experience is slightly greater than for external experience, and that residents are less tolerant of the lack of internal experience needs when there are multiple needs that are difficult to be met.

4.3. Strategies for Regeneration of Older Neighbourhoods

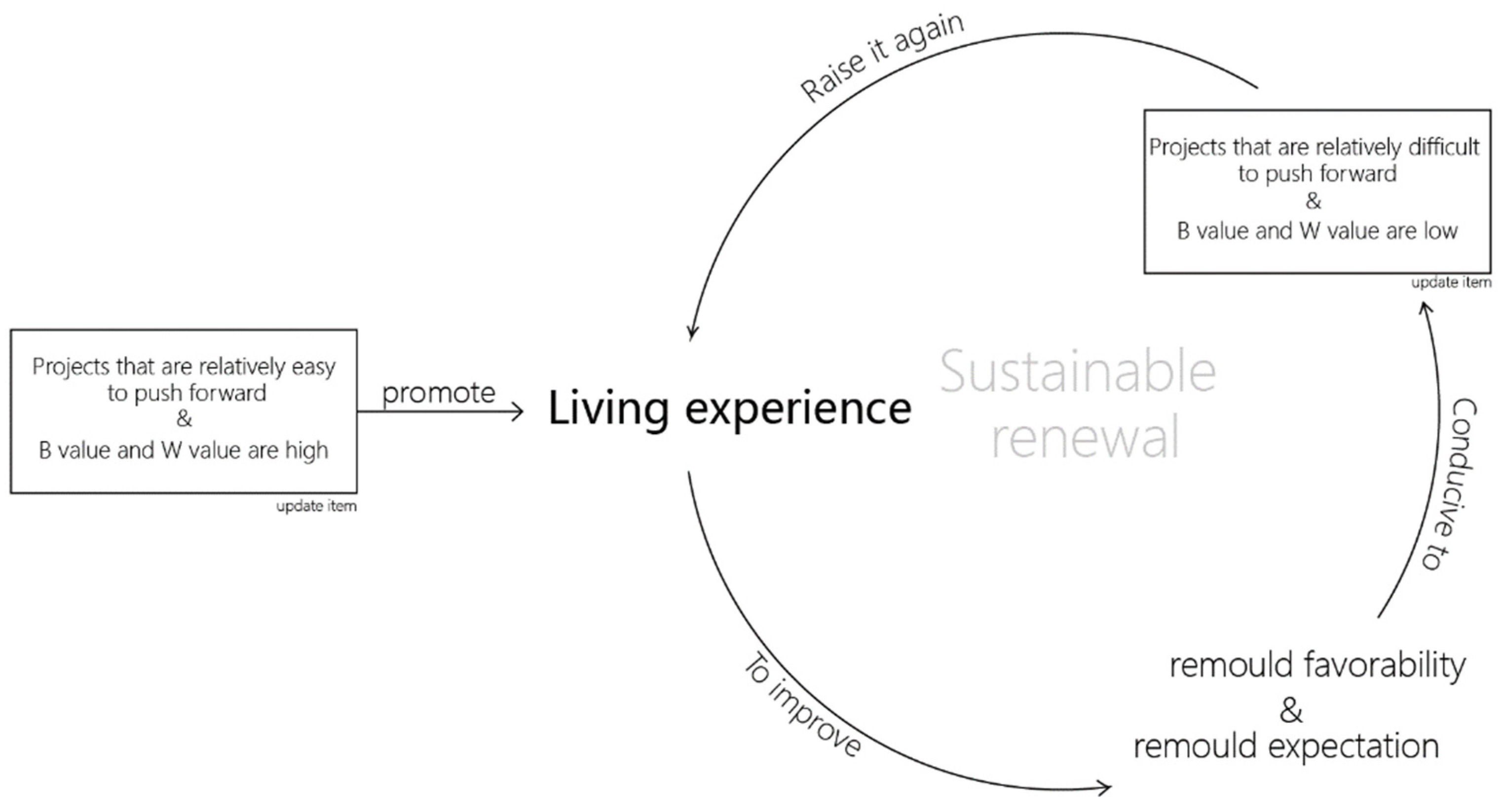

Considering the degree of impact of the remould project on the living experience and the degree of difficulty in promoting it, the remould strategy idea is constructed (

Figure 13) and sustainable renewal strategies are proposed.

(1) Regulating the management of old districts and establishing effective supervision.

Priority will be given to remedying fire hazards in old districts by installing additional fire-fighting facilities, inspecting and strictly controlling the situation of private wires, setting up corresponding fire escapes, putting up fire-fighting posters and raising residents’ awareness of firefighting. In terms of security, additional surveillance cameras, access control facilities, and burglar alarms were installed. Regular maintenance and supervision of the water, electricity, heat, and gas pipes in the community will reduce the number of cases where residents’ living experience is significantly affected by the loss of water and electricity in the community. In the course of the study, it was found that some of the unauthorised buildings on the ground floor were seriously encroaching on the public space of the majority of the residents, posing a safety hazard and greatly affecting the living experience of the residents. Therefore, it is necessary to strictly supervise illegal construction.

(2) Improving the spatial environment of old neighbourhoods and retrofitting necessary facilities.

Secondly, the old neighbourhoods located in the city centre section have a small number of parking spaces, so the government can take reasonable compensation, introduce social funds, build three-dimensional garages, and carry out effective management. Through field research in some of the old districts in Yuexiu District, some of the lifts in old districts have been retrofitted, but there are still many households to be retrofitted in constant negotiation. Such districts have been stalled in the lift retrofitting project due to the complex relationships of interests. While the majority of residents hope to complete the lift retrofitting as soon as possible, in response to this aspect of the problem, the neighbourhood committee can set up a mediation group to coordinate the interests of residents’ entanglement, so as to realise the lift retrofitting and improve the living experience. The overhead lines and lighting environment should be rectified by informing the relevant departments in a timely manner, rectifying the messy cables, cutting out the discarded cables, adjusting the areas where the lighting is insufficient at night, and installing reasonable lighting devices.

(3) Improving supporting facilities in old districts and enhancing the quality of the environmental experience in residential areas.

Finally, after the above-mentioned regeneration projects have been completed as a matter of priority and the living experience of residents has been enhanced to a certain extent, additional elderly facilities, electric bicycles, car charging facilities, fitness facilities, and community service stations, as well as an increase in the area of greenery, can be added to enhance the functional integrity of the district in all aspects and to comprehensively improve the living experience of residents in old districts.