Abstract

Scientists have recorded the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on small-scale fishers (SSFs), such as stagnating market demands and reduction in market price and income. Even though scientific evidence has heeded to these impacts, there is limited evidence regarding the long-term impacts and coping mechanisms of SSFs over longer periods. In addition, few studies have analysed these impacts and strategies from multiple perspectives. Our study aims to describe the perceived impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak on the communities of SSFs and the strategies adopted by them since the beginning of the outbreak in Trang Province, Thailand. Both qualitative and quantitative data obtained through semi-structured interviews indicated that, in the early stage of the outbreak, the SSFs used their natural, financial, and social capitals wisely; notably, human capitals were essential for the recovery in the later stages. Our findings suggested that an adaptive capacity to flexibly change livelihoods played an important role for the SSFs to cope with the outbreak; most importantly, our study indicated that, in a stagnating global economy, alternative income sources may not necessarily help SSFs.

1. Introduction

Small-scale fishers (SSFs) use small-sized vessels, simple or traditional fishing gear, and a small number of crew; they usually have family or local ownership [1]. SSFs typically operate near coastal shorelines and have access to only a relatively limited number of fish [2]. Part of the income source of approximately 180 million people in developing countries relies on SSFs [3]. In fact, approximately 50% of the seafood consumed in the world is caught by SSFs [4].

Despite the significance of SSFs, in terms of supporting the livelihoods of the poor and global seafood production, SSFs are considered to be particularly vulnerable in the world. Coastal communities, where large populations depend on marine resources for their livelihoods, tend to be vulnerable to sudden shocks and long-term changes [5]. Due to overfishing, habitat loss, pollution, and climate change, coastal small-scale fishing communities are experiencing decreased livelihood sustainability and increased food insecurity [6,7,8]. Additionally, compared with developed countries, SSFs tend to be more vulnerable to alterations in the global supply chains or price fluctuations [9], such as natural hazards and diseases, since they have fewer means to cope with these fluctuations [10].

Efforts to address these issues are particularly important for the SSFs, especially with respect to building resilience to adapt to any changes in social-ecological systems. Even though the literature on the theoretical aspects of vulnerability, adaptability, and resilience has increased, empirical studies on novel methods to operationalize the established theories in developing countries remain limited [11]. Considering the vulnerability of the SSFs, more studies are necessary to understand the effect of global socioeconomic and environmental changes on the SSFs, so as to plan for any rapid changes by strengthening the resilience of the SSFs [7].

Since early 2020, COVID-19 has spread worldwide at an unprecedented rate. Notably, even though studies remain limited, the latest literature reported various impacts of COVID-19 on SSFs. Measures and restrictions on social distancing during the pandemic has hindered SSFs from venturing out for fishing [12,13,14], and global industrial fishing activities were reduced by approximately 6.5%, owing to these restrictions [15]. In particular, serious impacts on fish catch and revenues have been reported in different areas around the world [16,17]. Thus, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the global seafood market and supply chain, thereby leading to a severe reduction in market demands and market price [9,18,19,20,21,22]. Notably, the SSFs who are dependent on export markets experienced a severe reduction of demands [13], and additionally, local markets were also affected [23]. SSFs suffered from income loss [4,9,14,17,24,25], unemployment [26,27], and food insecurity [28,29], since most of them did not have an alternative source of income. Therefore, some SSFs were even forced to take loans from local money lenders at high interest rates [24]. These situations also led to a loss of purchasing power [21], low consumer demands [24,30], and, often, severe psychological impacts and social unrests [28]. Moreover, social inequalities that caused restrictions on fishing activities, the barriers regarding fish product sales, and lack of social protection have increased the vulnerability of SSFs in some countries [21,31]. Furthermore, decreased capacity of monitoring and supervision [12] has led to an increase in the pressures associated with illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing within the areas used by SSFs [32]. Insufficient income and decreased tourism increase the pressure on local natural resources, to meet the needs for food and livelihoods [24]. A few studies on the coping strategies of SSFs during the pandemic reported that the SSFs helped each other by sharing food [33,34] or peddling caught fish in communities [35], while others stressed the importance of aid from public or private actors, financial assistance, and diversification of livelihoods [35,36].

The existing literature has significantly emphasized the socioeconomic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on small-scale fishing communities and their coping strategies within a relatively short time frame (i.e., mostly less than six months). However, evidence regarding the changing impacts over time and the detailed processes of how the SSFs have been adapting to the altering socioeconomic circumstances over a longer time frame (i.e., over a year), is limited. Thus, more studies that focus on the long-term effects of the pandemic are necessary [26]. Additionally, most articles have studied the impacts from a particular aspect (e.g., market economy), while few studies have comprehensively analysed the impacts in terms of natural, financial, social, human, and physical capitals. Notably, only a limited number of studies have conducted comparative analyses of different types of SSFs (e.g., fishers with and without alternative income sources), while discussing why some fishers are more severely affected than others.

To bridge these gaps, our study aims to explore the perceived impacts of COVID-19 outbreak on SSFs and document the coping strategies they implemented for over a year (i.e., before, during, and after the lockdown, and after a year from the lockdown), in Trang Province, southern Thailand. The questions addressed in this study are: (1) how did the SSFs perceive the impacts of COVID-19 outbreak over time? and (2) how have the SSFs addressed these impacts?

2. Methods

2.1. Site Description

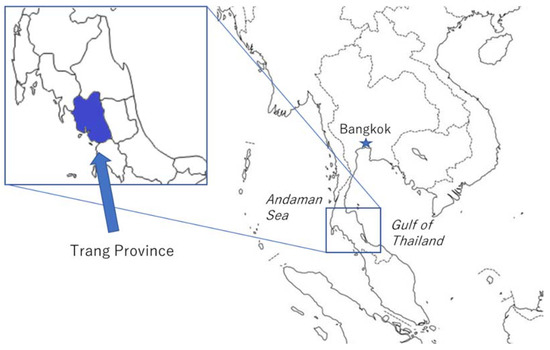

Thailand is one of the major fish producing countries in the world, with approximately 3.3 million individuals working in the fishing industry, of which 87% are categorized as SSFs [37]; the country catches 2.4 million tons of fish via marine/inland capture fisheries and aquaculture [38]. Trang Province (Figure 1) is situated in the southwestern coast of Thailand and is one of the six coastal provinces that open into the Andaman Sea, located along the Bay of Bengal. The coast of the Andaman Sea is blessed with rich marine ecosystems, such as mangrove forests (approximately 300 million m2) and seagrass beds (79 million m2), which are home to ~280 species of fish [39]. The rich marine resources have been attracting a number of fishers in this area. To date, 20,703 fishery establishments have been confirmed in 621 fishing villages along the entire Andaman Sea coast, while 3789 fishery establishments with 8459 fishers have been confirmed in 132 fishing villages in Trang Province [39]. Generally, the SSFs observed along the Andaman Sea coast fish within 3 km from the shore, using traditional or low efficient fishing gear [39]; often, the crews are comprised of family members, along with a few hired crew members [39]. The fishing ground has open access, and there is no specific limit or restriction on fish harvesting [39].

Figure 1.

Map of study site: Trang Province in southern Thailand.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

This study presents a case of coastal small-scale fishing communities in Trang Province, Thailand. The study was conducted in May–June 2021, through an in-depth qualitative interview survey, using partial collection of quantitative data. In total, 10 target villages were selected from the coastal areas of the Trang Province, which represented the socioeconomic and ecological characteristics of the region. To explore how the SSFs perceived and coped with the consequences under the pandemic, we conducted semi-structured interviews of 38 SSFs having diverse social attributes (i.e., 3–4 fishers from each village). The social attributes of the target fishers in the 10 villages were as follows. Their ages ranged from 20 to 66 (mean: 46; S.D.: 11.95); the male and female percentages were 55.3% and 44.7%. Though there were not many differences between the roles of men/women fishers in Trang Province, women fishers tended to have fewer opportunities to go out for fishing than men; therefore, the women helped maintain and repair the fishing gear/equipment, or were involved in selling the products to the middleperson. The majority of the respondents (71%) only received primary education or less, and a relatively small proportion had studied in high school (29%); there were no university graduates. Since the coastlines of the Trang Province are blessed with rich mangrove forests and seagrass beds [40], all the SSFs in the 10 villages had access to marine resources and their ecosystem services.

The interview questions followed the format built on the analytical framework (explained in 2.3), which asked the perceptions of the respondents on the impacts and coping strategies at four different stages: (1) before the COVID-19 outbreak in March 2020 (K), (2) during the initial lockdown in April–July 2020 (Ω), (3) after the initial lockdown in October 2020 (α), and (4) after one year from the initial lockdown in April 2021 (r). In each stage, the interview questions referred to the five aspects of the impacts and coping strategies, namely, natural, financial, social, human, and physical capitals (hereinafter referred to as NC, FC, SC, HC, and PC, respectively). For instance, regarding NC, we analysed the types of local natural resources (e.g., fish, crab, shrimp, fuelwood etc.) the SSFs used before the COVID-19 outbreak, discussed the effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on their usage of natural resources, and studied how they utilized these natural resources to overcome the difficulties during the pandemic (Supplementary Materials: Interview Guiding Questions). The qualitative interview data obtained from the 38 respondents was analysed based on an analytical framework, through the coding and categorization of data into themes.

During the interviews, we also acquired quantitative data on FC and NC for further analysis. Data were obtained by recording the self-reported monthly income (THB) and daily fish catch (kg) at four different stages before/during the outbreak. Since we found some quantitative data missing from the survey sheets of six respondents, the statistical analyses for income and fish catch were conducted using the data from only 32 respondents. In particular, the data regarding income were collected to examine the effectiveness of having an alternative income source, which is frequently suggested in the literature as one of the important factors for enhancing resilience [5,6,8,27,41,42,43]. Out of the 32 respondents, 13 fishers had an alternative income source (i.e., daily labour at oil palm/rubber plantations), from which they earned income in addition to fisheries. The other 19 fishers solely relied on catching and selling fish for their income.

The data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 (manufactured by IBM, New York, USA). To compare the income levels at different stages, we applied the Friedman test, followed by the Bonferroni correction. First, we classified the target fishers into fishers having single income source (i.e., fishers who rely only on fisheries for their income; n = 19) and fishers having an alternative income source in addition to fisheries (n = 13). Second, we divided the target fishers into ‘flexible fishers’ (fishers who initiated at least one new challenge for income generation during the COVID 19 outbreak; n = 19) and ‘non-flexible fishers’ (fishers who hesitated to initiate new challenge during the COVID 19 outbreak; n = 13). Using this categorization, we verified whether the income levels of the fishers changed significantly from one period to another and compared the differences among the groups. In the statistical analyses, we used the data of median income, instead of mean income, since mean values tend to be influenced by outliers.

The second author and their colleagues from the Save Andaman Network Foundation (a Thai NGO) met all the respondents individually and conducted the interview surveys. The surveyors received training to not only understand the objective of the study and the analytical framework, but also learn to effectively conduct semi-structured interviews. To avoid biased responses, the other three Japanese authors did not join the interviews. To confirm whether the questions were understandable, pre-tests were completed by the non-target fishers before the survey. Before starting the surveys, the surveyors explained the objectives of the study, explained how the data may be used, and obtained informed consent from all the respondents. The answers obtained from the respondents were recorded in Thai language, and, then, translated into English.

2.3. Analytical Framework

This study was built on an analytical framework that combined two different models, the ‘Adaptive Cycle Model (ACM)’ developed by Holling and Gunderson [44] and the ‘Sustainable Livelihood Framework (SLF)’ proposed by the Department for International Development (DFID) [45]. The ACM was developed to understand the resilience of different participants by unravelling the dynamics of social-ecological systems; the model consists of four specific stages: the exploitation phase (r) characterized by growth and seizing of opportunities, conservation phase (K; representing stability and increasing rigidity [fore-loop]), release phase (Ω, denoting the period of decline and destruction), and reorganization phase (α, for innovation and restructuring [back-loop]) [46]. The former (r to K) consists of a slowly increasing phase, with growth and accumulation, whereas the latter (Ω to α) consists of a short-term phase of destruction, followed by reorganization and leading to renewal [47,48]. However, this model does not have a numerical scale bar that determines the length of time.

By contrast, the SLF places the poor at the centre of the development process and aims to increase the sustainability of their livelihoods. This framework focuses on livelihood asset analysis, where sustainability is considered in terms of the available capitals (i.e., NC, FC, SC, HC, and PC), while examining the vulnerability context in which these assets exist [49]. The SLF can identify the connections between people and the environment that affects their livelihood strategies and outcomes [50]. It aims to make their lives more sustainable by: (i) improving access to better education, training, technology, information, nutrition, and health; (ii) creating a social environment that supports the poor, based on cooperation and collaboration; (iii) ensuring adequate access to and control over natural resources; (iv) improving access to basic infrastructure; (v) improving access to financial and economic resources; and (vi) supporting a variety of survival and livelihood strategies [51].

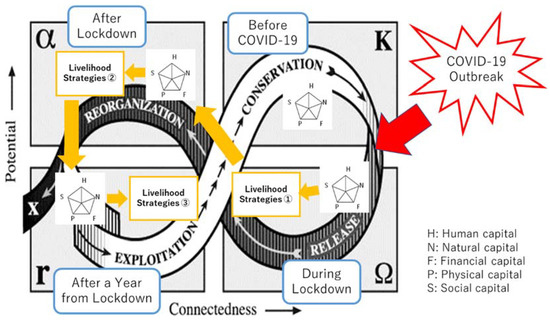

In this study, we combined the two frameworks (ACM and SLF) for the following two reasons. First, the SLF does not sufficiently present the time frame. Combining the SLF and ACM enables us to understand how each capital asset and livelihood strategies change over time, throughout the four stages of adaptation. Second, the ACM does not fully identify the detailed components or interactions among the different factors that affect the social-ecological systems in the four stages. Combining the framework allowed us to analyse the types of capital that may influence the social-ecological system in each phase of adaptation, while explaining how different capitals may affect one another over time (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Analytical Framework: Adaptive Cycle Model (ACM) + Sustainable Livelihood Framework (SLF) (Revised from [44,45]).

We assumed that the COVID-19 outbreak served as an external shock, which influenced the social-ecological system of SSF communities to alter its status from the K to Ω phases, since it disrupted their stable lives and led to a huge loss of resources. The K and Ω phases can be considered as the pre-COVID-19 and lockdown periods, respectively. Since people started to restructure their livelihoods after the lockdown, this stage was identified as the α phase. Finally, the period one year after the lockdown was set as the r phase, as this was the time when people gradually sought better livelihood opportunities.

3. Results

3.1. Before COVID-19 Outbreak (March 2020; K Phase)

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, the median daily fish catch (excluding self-consumption) among all the target respondents were 7.0 kg/day (NC), while the median monthly income of all the interviewed fishers reached THB 8500 (FC). Nearly 100% of the interview respondents acknowledged that they had strong trustworthy relationships with their family members, neighbours, colleagues, and community members before the COVID-19 outbreak (SC). All respondents answered that they had no specific problems regarding their health conditions, including both physical and mental aspects (HC). As for their skills or knowledge, the vast majority (94.7%) responded that they knew how and where to catch fish, crabs, or shrimps, but did not have any other specific skills or knowledge, since most of them (71%) only had primary education (HC). Most of the interviewees possessed minimum gears and tools necessary for fishing, including a small-sized fishing boat, fishing nets, and traps, in which the types depended on the targeted species of fish (PC).

3.2. During Lockdown (April–July 2020, Ω Phase)

The majority (95%) of respondents claimed that during the lockdown, they had difficulties in continuing fishing activities, owing to the closures of both domestic and international fish markets, strict government restrictions on leaving their houses, and the fear of infection. The data on the daily fish catch, as well as income, during this period were not available (NC and FC). Most respondents mentioned that, during this period, they continued fishing only for their own food; they did not catch fish for business purposes. Although we could not quantify the financial status during the lockdown, we presumed that most target fishers had limited income during this period. By contrast, to secure their food and reduce their expenditures to purchase other foods, such as chicken or beef, 28.9% of the interviewees depended on seafood (e.g., fish, crab, shrimp, and shellfish; NC). They managed to go fishing nearby during the unrestricted time slots. Some fishermen households consumed seafood more than twice per day. Furthermore, 92.1% of the respondents confessed that they had to rely on their savings, and that they eventually used up all their savings to make up for the lack of income (FC). We also confirmed that 68% of the respondents received an emergency subsidy of THB 15,000 from the Ministry of Finance of Thailand during April–June 2020, to compensate for their income loss.

The majority of the respondents perceived that, during the lockdown, their social relationships weakened, compared to the situation before the outbreak (SC). The ratio of the respondents who perceived that the relationships with their family members were weakened reached 84.2%. Similarly, 76.3% perceived that their relationships with the neighbours weakened. Additionally, 63.2% and 60.5% of the respondents perceived that the relationships with colleagues and community members weakened, respectively.

Furthermore, 32% of the respondents confessed that the reduction in income impacted the relationships within their family. They explained that the lack of money led to difficulties in sustaining their livelihoods, causing stressful conditions within their families. Further, interviewees explained that staying at home together for a long time without being able to go out also had a negative influence on their family relationships.

During lockdown, the government imposed strict regulations restricting social activities, such as village meetings, cultural events, or wedding ceremonies, which deprived people of opportunities to meet and socialize. In addition, they encountered difficulties in meeting each other, owing to the added fear of virus infection. Moreover, interviewees explained that people who lost their income or jobs hesitated to meet their neighbours or community members because they were embarrassed about their financial situations.

On the other hand, all interviewees acknowledged sharing their fish, shellfish, shrimps, or crabs with neighbours or community members, despite their fear of infection. They gradually started helping each other, while taking necessary measures to reduce the risks of infection (e.g., wearing masks and maintaining social distance). In most cases, people shared some of the seafood they caught for self-consumption. Approximately 20–40% of the respondents mentioned that their relationships with neighbours, colleagues, and community members strengthened during the pandemic. They explained that helping each other by sharing food or information to endure the difficult situations strengthened their social relationships even more than that before the outbreak.

Regarding HC, all respondents (100%) expressed their concerns about mental stress, particularly during the lockdown period. Due to the government regulations (e.g., prohibition on going outside and banning social events) during this period and the fear of infection, many people had limited opportunities to leave their houses or meet people other than their family members, which increased mental stress. As for physical health, among all the respondents, nobody mentioned that the respondent themselves or their families, neighbours, or colleagues suffered or were infected by COVID-19 at the time of the interviews. Eventually, they all learned and adopted ways to reduce risks of infection (e.g., wear masks, keep social distances, and comply with hygiene rules). The other aspect of HC explained by the respondents was related to knowledge and skills. All interview respondents (100%) answered that the COVID-19 outbreak did not affect their knowledge or skills during the lockdown. Additionally, regarding PC, all the respondents (100%) answered that the COVID-19 outbreak did not have any specific impacts on their possessions during the lockdown period.

3.3. After Lockdown (October 2020; α Phase); a Year from the Lockdown (April 2021; r Phase)

3.3.1. Natural Capital (NC)

During the α phase, the median daily fish catch of all the target respondents was 5.0 kg/day, which was smaller compared to the catch before the outbreak, while 71% of the respondents perceived the reduction in the market and market price as the major reason causing the reduced fish catch. The interviewees mentioned that they had to catch less amounts of fish than before, since they could not sell them to the middleperson or markets at a proper price, owing to the severe decline in the global and domestic market demand. Though some fishers wanted to increase their fish catch to cope with the reduction of market price, they could not do so because of their limited fishing gear and small-sized boats. Others had better fishing gear and increased their fish catch; however, their income was not recovered, owing to the low market price and limited markets. After a year from the lockdown, median fish catch (excluding self-consumption) among the target fishers remained at 5.0 kg/day. Though the respondents acknowledged that domestic markets were gradually recovering to some extent, they perceived that international markets were still inactive, and the difficulty in finding enough markets or middleperson as in the pre-COVID-19 period, remained.

The fishers continued to consume the seafood they caught, and 60.5% of the respondents mentioned that they started growing agricultural products and medicinal plants (e.g., chili, ginger, and galangal) in their home gardens for self-consumption. After a year from the lockdown, 24% of respondents changed their target fish to the ones that had relatively higher demands and higher market price (e.g., jellyfish).

Furthermore, 65.8% of the respondents noted that many villagers who used to work for tourism-related businesses (e.g., hotels, restaurants, tour guide, and travel agent) lost their jobs because of the impact of the pandemic on tourism and started to engage in fisheries. While local fish markets gradually started to reopen after the lockdown period, it was still difficult for tourism companies to restart their businesses; this encouraged tourism employees to change their occupation. The interviewees explained that because many of the parents or relatives of the unemployed people were engaging in fisheries, it was relatively easy for them to start working in fisheries by receiving necessary support or training. They also mentioned that fisheries seemed to be an attractive income option, because they could at least survive by consuming fish. By contrast, there were a certain portion of interview respondents (76%) who expressed a concern about fish stocks (including crabs or shrimps) being decreased, owing to increased pressure from fisheries or self-consumption, which led to a reduction in fish catch a year after the lockdown.

3.3.2. Financial Capital (FC)

During the α phase, the median monthly income of all the target fishers was THB 4500, which was still 47% lower than their income level before the outbreak, and 77% of the respondents indicated either less market demand or lower market price as the major reasons for the impact. The fact that they could not sell the caught fish to the middleperson and that the market price of fish remained to be cheap made it difficult to increase their income levels.

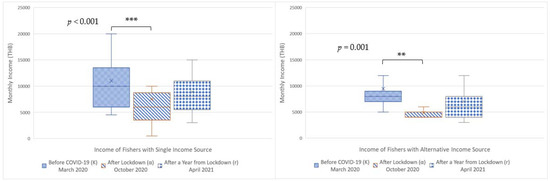

Their income declined not only among the fishers having a single income source (who relied only on fisheries for their income), but also fishers who had alternative income sources in addition to fisheries. The median income of the fishers having alternative income sources decreased from THB 8000 (S.D.: 6761.922) to THB 4000 (S.D.: 3490.371) during the K and α phases, respectively, and slightly increased to THB 6000 (S.D.: 4736.655) in the r phase. The income of the fishers who relied on a single source of income reduced from THB 10,000 (S.D.: 6639.528) to THB 6000 (S.D.: 6929.997) gradually restoring to THB 8000 (S.D.: 5108.759) in the r phase (Figure 3). Our statistical analysis, using the Friedman test with Bonferroni correction, indicated that the median income levels of both the fishers decreased significantly from the K to α stage (single: p < 0.001 ***/alternative: p = 0.001 **), while no significant differences were observed between the α and r phases and K and r phases. Their alternative income sources were represented by daily labour at oil palm or rubber plantations, which, as the respondents mentioned, were also influenced by the restriction on production under the stagnating global economy.

Figure 3.

Monthly income (THB) of fishers having single/alternative income sources during three different stages before/during the COVID-19 outbreak in Trang Province, Thailand (single: n = 19; alternative: n = 13/**: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001).

However, the expenditures of the fishermen only showed a slight decrease, from a median of THB 7000 (in the K phase) to THB 6000 (in the α phase), equivalent to a 14.3% decrease. The respondents believed that the price of commodities increased due to the stagnating supply chain and that it would be difficult to reduce their expenses to sustain the daily life of their family members (e.g., feeding their families, paying electricity costs, and taking care of sick elders).

The following coping strategies to address the financial crisis were observed after the lockdown (α–r phase). Since many of the respondents used up all their savings during the lockdown, 73.7% confessed going into debt. They borrowed money from relatives or family members (23.7%), informal money lenders (21%), banks (18.4%), or neighbours (10.5%) because they could not continue their livelihoods with their severely reduced income. While some people had the capacity to deal with the official procedures required to obtain a loan from a bank (e.g., providing collaterals and dealing with paper works), others did not have such capacity and had to borrow money from informal money lenders at high interest rates.

In addition, 71% of the interviewees sold fish, shrimp, shellfish, or crabs to their neighbours, colleagues, and local merchants, which enabled them to earn a minimum income that helped them to survive. Since the international markets were still inactive even after a year from the lockdown, they utilized their local social relationships to survive. Some interview respondents mentioned that selling products among community members further strengthened their social relationships, which was once weakened owing to the lockdown.

Moreover, 21% of fishers started online sales to sell products to domestic markets, including large cities, such as Bangkok. Interviewees explained that their friends or family members who had the skills to sell products online (e.g., by using Facebook) taught them such skills, which enabled them to sell the products to a wider group of people. In Thailand, a private delivery company provided services to deliver various products to many parts of Thailand without any cost to the fishers, which made it easier for them to sell their seafood products to the domestic consumers. Furthermore, 11% of the fishers started to produce value-added products (e.g., crab sauce) to increase their income; such products were also sold through online markets. Respondents mentioned that they learned or taught such skills among friends to overcome the issues of low market price and reduced income.

Through such strategies, the income of fishermen appeared to gradually recover in the later stages; in April 2021, the median monthly income of the respondents was restored to THB 6500. Some interviewees stated that the domestic market economy was gradually reopening, and that their efforts for increasing their income had started to bear fruit. Thus, the median monthly income that used to be THB 8500 (S.D.: 6623.732) before the COVID-19 outbreak in March 2020 (K phase) and decreased significantly to THB 4500 (S.D.: 5867.295) in October 2020 (α phase), recovering to THB 6500 (S.D.: 4969.641) in April 2021 (r phase), one year after the initial outbreak.

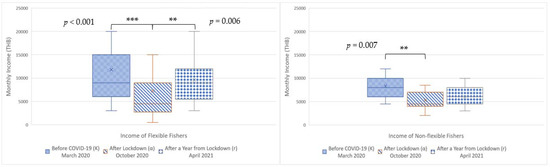

Among the respondents, two major groups with different coping strategies were determined. One comprised of fishers who had a flexible approach and initiated new challenges to increase their income (e.g., sell products online and produce value-added products). The other comprised of those who tended to hesitate to endure new challenges to increase their income and mainly relied on the existing NC, SC, and FC. The former group (i.e., ‘flexible fishers’) succeeded in restoring their median monthly income to THB 9000 (S.D.: 5804.314) in stage r, which was equivalent to their income in stage K (S.D.: 8143.436), even though it was once reduced to THB 4500 (S.D.: 7429.985) in stage α. By contrast, the latter group (i.e., ‘non-flexible fishers’) were able to only slightly restore their income from THB 4500 (S.D.: 1888.732) in stage α to THB 6000 (S.D.: 2145.359) in stage r, which was still much lower than the THB 8000 (S.D.: 2454.065) that the fishers earned in the K phase (Figure 4). The Friedman test combined with Bonferroni correction indicated that the median income levels of both the flexible and non-flexible fishers reduced significantly from stages K to α (flexible: p < 0.001 ***; non-flexible: p = 0.007 **). However, the income levels of the flexible fishers increased significantly from stages α to r (p = 0.006 **), while the income levels of non-flexible fishers exhibited no significant differences between stages α and r.

Figure 4.

Monthly income (THB) of flexible/non-flexible fishers during the three different stages before/under the COVID-19 outbreak in Trang Province, Thailand (flexible: n = 19; non-flexible: n = 13/**: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001).

3.3.3. Social Capital

Since the lockdown period, people learned to avoid risks of infection in their daily lives. After the lockdown, most respondents (97.4%) mentioned that they became accustomed to wearing a mask and maintaining social distance while taking walks or meeting with their colleagues or community members. In stage r, they were able reorganize social events, such as village meetings or wedding ceremonies, while adopting the necessary measures to prevent infection.

While they still continued to share caught seafood among neighbours or colleagues, some of them also shared their knowledge or skills. People who had the skills to sell products online educated their family members or friends; thus, the fishers could sell their fisheries products to consumers outside their village. Furthermore, they also learned or taught each other how to produce value-added products, which provided another opportunity to increase their income.

3.3.4. Human Capital (HC)

After the lockdown, people were allowed to leave their houses, go fishing with their colleagues, and socialize with other community members. The interviewees perceived that this greatly contributed to alleviate their mental stress.

Some of the interview respondents acknowledged that the impacts of COVID-19 provided an opportunity for them to learn new knowledge or skills, to overcome the issue of income loss, while 21% of interviewees mentioned that they learned how to sell fisheries products online from their friends, neighbours, or family members, to expand their market to the entire country. To address the issues of low market price, 11% learned how to produce value-added products (e.g., crab sauce). For example, one person learned and started to raise crabs in a pond, since they wanted to keep them for a while and sell them when the market price increases. Furthermore, the people who were unemployed and used to engage in tourism related businesses before the pandemic learned to conduct fisheries practices.

3.3.5. Physical Capital (PC)

One fisher confessed that they had to sell their fishing boat and gear to cover their income loss and feed their family. They asked their colleagues to share the boats or gears with them to continue fishing and hoped to purchase a new one once they earned more money. Others also mentioned that they had to pledge their houses or accessories as collaterals to borrowing money from the banks. However, some fishers (21%) strategically purchased a new fishing gear/boat, or repaired their gear/boat to increase their fish catch (mostly by taking loans), to cope with the lower income resulting from the lower market price.

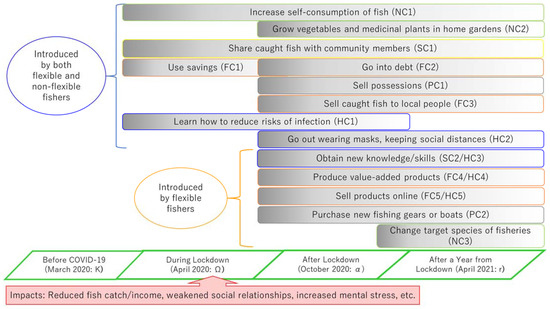

3.4. Summary of Coping Strategies

The major coping strategies described above are summarized in Figure 5. The box at the bottom of the figure indicates the major impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak, and the bar above it represents the time axis (i.e., the four stages before/during the COVID-19 outbreak), and the horizontal boxes present the coping strategies of the target fishers. This diagram portrays the types of strategies adopted in each stage. The nine strategies were identified among both flexible and non-flexible fishers, while the five strategies (lower part) were observed only among the flexible fishers.

Figure 5.

Coping strategies introduced by flexible/non-flexible fishers observed in different stages during the COVID-19 outbreak in Trang Province, Thailand.

4. Discussion

The major impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak perceived by the SSF in Trang Province during the lockdown (Ω) were as follows: (1) reduction in fish catch (NC); (2) decrease in income (FC); (3) weakened social relationships (SC); and (4) increased mental stress (HC). The impacts associated with reduced market demands, lower market price, and decreased income matched with the case study conducted in other countries [24,35,36]. The major coping strategies observed during the lockdown (Ω) were as follows. The fishers consumed the fish, crabs, and shrimps caught by themselves to secure their food source and reduce expenditure (NC1); they shared seafood with neighbours, colleagues, and community members (SC1); and they used the money from their savings (FC1). Moreover, to protect themselves from the virus, they adopted safety measures to reduce the risk of infection (HC1). Thus, their responses seemed to strongly emphasize on fulfilling their immediate needs by obtaining food and the minimum amount of money required for living, since the top priority for the fishers was their physical survival. Our findings align with the literature that NC [41], SC [52], and FC [53] play an important role as safety nets during crisis.

After the lockdown (α–r phases), since many of them used up their savings, the fishers were in debts; they borrowed money from relatives, neighbours, informal money lenders, or banks (FC2). Another strategy frequently observed was to sell caught seafood to neighbours, colleagues, or other community members to earn a minimum income (FC3). These strategies were also reported in other countries [24,35]. Further, respondents started to grow vegetables and medicinal plants in their home gardens to secure their food or medicine and save money (NC2). One of them sold their fishing boat to make up for their income loss (PC1). Furthermore, after people were gradually allowed to leave their homes and meet with other people, they started to socialize by wearing masks and maintaining social distances (HC2). This enabled them to restrengthen their social relationships through helping each other by sharing knowledge and skills (SC2/HC3).

While these diverse coping strategies were commonly observed among the target respondents, a certain portion of target fishers had the capacity to acquire new knowledge (SC2/HC3) and flexibly initiate new challenges to improve their livelihoods. Some learned from their family, neighbours, or other community members to produce value-added products (FC4/HC4), or sell products online (FC5/HC5). Others changed the target species to the ones that had higher market demand and price (NC3) or purchased new fishing gear/boats by taking loan to increase fish catch (PC2).

Fishers who conducted these flexible coping strategies after the lockdown until April, 2021 (stage r), succeeded in restoring their income levels after the severe impact observed in April–July 2020 (stage Ω) and October 2020 (stage α). Our statistical analysis indicated that the flexible fishers’ income levels increased significantly from stages α to r. In contrast, the other fishers who hesitated to explore new avenues to increase their income and mainly relied on existing NC, SC, and FC failed to restore their income. Even though coping strategies, such as increasing self-consumption of seafood or growing vegetables in home gardens, using money from their savings, taking loans, and sharing or selling caught fish among community members, were widely observed among most respondents, these efforts were insufficient to restore their income levels. Since the amount of fish catch did not increase in April 2021, we presumed that the flexible fishers were capable of increasing their income levels by improving the unit price of the products or finding a better market, whereas the non-flexible fishers failed to do so. We suggest that these challenges were possible among the fishers who had higher flexibility and learning ability, which can be associated with their HC.

Additionally, SC played an important role in strengthening HC. Since the flexible fishers utilized their social relationships with their neighbours, family members, or other community members to obtain new knowledge or skills, our findings implied that SC could provide opportunities for fishers to access such useful knowledge and build their adaptive capacities. Thus, we argue that HC together with SC were crucial in enhancing the resilience of SSFs at the later stages (α-r) of the adaptive cycle.

The literature stresses the importance of diversification of livelihoods or alternative income source in enhancing the resilience of SSFs [5,6,8,27,41,42,43]. However, our findings indicated that alternative income sources did not necessarily support the SSFs during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the global market economy was stagnant. Our statistical analyses demonstrated that the income levels of both fishers with and without alternative income sources experienced a significant reduction during stage α. Moreover, the results revealed that the fishers with alternative income sources failed to significantly increase their income levels from stages α to r. Considering the fact that alternative income sources were represented by daily labour at oil palm or rubber plantations, we presumed that such businesses were also heavily affected by the stagnation of global market economy, just like the fisheries. Thus, our results indicated that simply obtaining alternative income sources does not necessarily help strengthen SSF’s resilience under crises.

Even though we need more research to generalize these findings, our results imply that the diversification of livelihood alone is insufficient to strengthen resilience, particularly under global economic stagnation. Rather, we argue that ‘adaptive capacity’ (particularly, flexibility in strategies and learning ability to respond to changes), as explained by Cinner et al. [54] and Cinner and Barnes [55], is important in enhancing the resilience of SSFs during crisis. Since natural-resource-dependent communities tend to lack skills or capacity to change their occupation and find alternative livelihoods [56], the capacity of rural households to become flexible is essential for strengthening resilience [42]. Yet, we do not deny the importance of alternative income sources. As Bassett et al. [57] stressed on the significance of local, domestic supply chains, and networks in enhancing the resilience of SSFs, we suggest that their alternative income sources should not be dependent on the global market and should be incorporated within the local or domestic market economy.

The major limitation of this study is the small sample size and limited statistical representativeness; further studies are necessary for generalizing our outcomes. Nonetheless, we believe that conducting an in-depth case study based on the above-mentioned analytical framework would make a unique contribution to the existing literature, by offering a deeper and a more comprehensive understanding of the perceptions and coping strategies of SSFs over time.

We recommend future studies to compare the impacts of the pandemic between fishers with and without alternative income sources in other regions or countries having different socioeconomic contexts. Further, it would be also interesting to study the differences in the impacts among different types of income sources (e.g., jobs that are dependent on international and local markets). Finally, we expect researchers to apply our analytical framework to assess the impacts and coping strategies in other regions or countries to obtain a more comprehensive understanding for a longer time frame. Such studies may contribute by suggesting better approaches for enhancing the resilience of SSFs around the globe.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we explored the perceived impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak in Trang Province, Thailand, and identified the coping strategies adopted by SSFs over a year after the lockdown, while understanding the roles of NC, FC, SC, HC, and PC in determining the resilience of small-scale fishing communities.

Our study results indicated that the SSFs have been affected by severe impacts, such as reduced fish catch, loss of income, and weakened social relationships etc. Under such circumstances, the SSFs focused on fulfilling their immediate needs by relying on existing NC, SC, and FC in the early stage. In the later stages, we found that HC, together with SC, played a significant role in introducing new coping strategies, which helped the fishers to restore their income levels. Since the target respondents having such characteristics successfully increased their income after the lockdown, we argue that HC, namely adaptive capacity (particularly flexibility and learning ability), is crucial in strengthening the resilience of SSFs during a crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even though the existing literature emphasizes the importance of alternative income sources in enhancing resilience, our study revealed that the income levels of fishers with and without alternative income sources were severely affected after the COVID-19 outbreak. Therefore, we suggest that providing alternative livelihood opportunities alone is insufficient, and that the income sources should be based on an economic activity that is not dependent on the global market economy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su14052865/s1, Interview Guiding Questions

Author Contributions

This research was initiated by Y.A. and S.I. under the supervision of M.U. and M.S. conducted the field interview survey and summarized the data. The writing process was led by Y.A. in collaboration with S.I. All authors participated in the revision process. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Keidanren Nature Conservation Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Shinshu University, Japan (Date: 11 May 2021; No.: 300).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the respondents involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All the publishable data related with this study are presented in the manuscript. However, individual data obtained through the interview survey cannot be disclosed because they include privacy related information.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Save Andaman Network Foundation and Ramsar Centre Japan for their dedicated support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lunn, K.E.; Dearden, P. Monitoring small-scale marine fisheries: An example from Thailand’s Ko Chang archipelago. Fish. Res. 2006, 77, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuchiracheeva, S.; Demaine, H.; Shivakoti, G.P.; Ruddle, K. Systematizing local knowledge using GIS: Fisheries management in bang Saphan Bay, Thailand. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2003, 46, 1049–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, H.; Adhuri, D.S.; Adrianto, L.; Andrew, N.L.; Apriliani, T.; Daw, T.; Evans, L.; Garces, L.; Kamanyi, E.; Mwaipopo, R.; et al. An ecosystem approach to small-scale fisheries through participatory diagnosis in four tropical countries. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 36, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.J.; Burnham, T.L.U.; Mansfield, E.J.; Crowder, L.B.; Micheli, F. COVID-19 reveals vulnerability of small-scale fisheries to global market systems. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrol-Schulte, D.; Gorris, P.; Baitoningsih, W.; Adhuri, D.S.; Ferse, S.C.A. Coastal livelihood vulnerability to marine resource degradation: A review of the Indonesian national coastal and marine policy framework. Mar. Policy 2015, 52, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satumanatpan, S.; Pollnac, R. Resilience of small-scale fishers to declining fisheries in the Gulf of Thailand. Coast. Manag. 2020, 48, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan-Hallam, M.; Bennett, N.J.; Satterfield, T. Catching sea cucumber fever in coastal communities: Conceptualizing the impacts of shocks versus trends on social-ecological systems. Glob. Environ. Change Hum. Policy Dimen. 2017, 45, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mozumder, M.M.H.; Wahab, M.A.; Sarkki, S.; Schneider, P.; Islam, M.M. Enhancing social resilience of the coastal fishing communities: A case study of Hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha H.) fishery in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fiorella, K.J.; Bageant, E.R.; Mojica, L.; Obuya, J.A.; Ochieng, J.; Olela, P.; Otuo, P.W.; Onyango, H.O.; Aura, C.M.; Okronipa, H. Small-scale fishing households facing COVID-19: The case of Lake Victoria, Kenya. Fish. Res. 2021, 237, 105856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Chuenpagdee, R. Negotiating risk and poverty in mangrove fishing communities of the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Marit. Stud. 2013, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwarz, A.M.; Béné, C.; Bennett, G.; Boso, D.; Hilly, Z.; Paul, C.; Posala, R.; Sibiti, S.; Andrew, N. Vulnerability and resilience of remote rural communities to shocks and global changes: Empirical analysis from Solomon Islands. Glob. Environ. Change Hum. Policy Dimen. 2011, 21, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. How Is COVID-19 Affecting the Fisheries and Aquaculture Food Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small-Scale Fishermen Suffering Significantly from COVID-19 Pandemic. Seafood Source. Available online: https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/small-scale-fishermen-suffering-significantly-from-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Giannakis, E.; Hadjioannou, L.; Jimenez, C.; Papageorgiou, M.; Karonias, A.; Petrou, A. Economic consequences of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) on fisheries in the eastern Mediterranean (Cyprus). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Fisheries during COVID-19. Global Fishing Watch. Available online: https://globalfishingwatch.org/data/global-fisheries-during-covid-19 (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Coll, M.; Ortega-Cerdà, M.; Mascarell-Rocher, Y. Ecological and economic effects of COVID-19 in marine fisheries from the Northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 255, 108997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo-Núñez, J.; Mendo, T.; Gozzer-Wuest, R.; Mendo, J. Impacts of COVID-19 on the value chain of the hake small scale fishery in northern Peru. Mar. Policy 2021, 134, 104808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korten, T. With Boats Stuck in Harbor Because of COVID-19, Will Fish Bounce Back? Smithson. Mag. 2020, 1–7. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/fish-stop-covid-19-180974623/accessed (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Love, D.C.; Allison, E.H.; Asche, F.; Belton, B.; Cottrell, R.S.; Froehlich, H.E.; Gephart, J.A.; Hicks, C.C.; Little, D.C.; Nussbaumer, E.M.; et al. Emerging COVID-19 impacts, responses, and lessons for building resilience in the seafood system. Glob. Food Sec. 2021, 28, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, E.O.; Blankson, G.K.; Sabau, G. Building back sustainably: COVID-19 impact and adaptation in Newfoundland and Labrador fisheries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangubhai, S.; Nand, Y.; Reddy, C.; Jagadish, A. Politics of vulnerability: Impacts of COVID-19 and Cyclone Harold on Indo-Fijians engaged in small-scale fisheries. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 120, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Ercilla, I.; Espinosa-Romero, M.J.; Fernandez Rivera-Melo, F.J.; Fulton, S.; Fernández, R.; Torre, J.; Acevedo-Rosas, A.; Hernández-Velasco, A.J.; Amador, I. The voice of Mexican small-scale fishers in times of COVID-19: Impacts, responses, and digital divide. Mar. Policy 2021, 131, 104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishing Communities Bear Brunt of Lockdown. Available online: https://business.inquirer.net/294753/fishing-communities-bear-brunt-of-lockdown (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Sunny, A.R.; Sazzad, S.A.; Prodhan, S.H.; Ashrafuzzaman, M.; Datta, G.C.; Sarker, A.K.; Rahman, M.; Mithun, M.H. Assessing impacts of COVID-19 on aquatic food system and small-scale fisheries in Bangladesh. Mar. Policy 2021, 126, 104422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truchet, D.M.; Buzzi, N.S.; Noceti, M.B. A “new normality” for small-scale artisanal Fishers? The case of unregulated fisheries during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Bahia Blanca estuary (SW Atlantic Ocean). Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 206, 105585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.; Anelli Monti, M.; Toninato, G.; Silvestri, C.; Raffaetà, A.; Pranovi, F. Lockdown: How the COVID-19 pandemic affected the fishing activities in the Adriatic Sea (central Mediterranean Sea). Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Mishra, A.; Nuthalapati, C.S.; Bellemare, M.F.; Zilberman, D. COVID-19’s disruption of India’s transformed food supply chains. Econ. Pol. Wkly. 2020, 55, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Das, B.K.; Roy, A.; Som, S.; Chandra, G.; Kumari, S.; Sarkar, U.K.; Bhattacharjya, B.K.; Das, A.K.; Pandit, A. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on small-scale fishers (SSF) engaged in floodplain wetland fisheries: Evidences from three states in India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 29, 8452–8463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WFP Chief Warns of “Hunger Pandemic” as COVID-19 Threatens Food Security. Devex. (Blog). Available online: https://www.devex.com/news/wfp-chief-warns-of-hunger-pandemic-as-covid-19-threatens-food-security-97058 (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Hoque, M.S.; Bygvraa, D.A.; Pike, K.; Hasan, M.M.; Rahman, M.A.; Akter, S.; Mitchell, D.; Holliday, E. Knowledge, practice, and economic impacts of COVID-19 on small-scale coastal fishing communities in Bangladesh: Policy recommendations for improved livelihoods. Mar. Policy 2021, 131, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowman, M.; Sunde, J.; Pereira, T.; Snow, B.; Mbatha, P.; James, A. Unmasking governance failures: The impact of COVID-19 on small-scale fishing communities in South Africa. Mar. Policy 2021, 133, 104713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada Pulls At-Sea Observers from Fishing Boats Due to Coronavirus Pandemic. The Narwhal. Available online: https://thenarwhal.ca/fisheries-oceans-canada-pulls-at-sea-observers-fishing-boats-coronavirus-covid-19/accessed (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Scottish Fishermen Turn to Food Banks as COVID-19 Devastates Industry. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/apr/10/scottish-fishermen-turn-to-food-banks-as-covid-19-devastates-industry (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Bennett, N.J.; Finkbeiner, E.M.; Ban, N.C.; Belhabib, D.; Jupiter, S.D.; Kittinger, J.N.; Mangubhai, S.; Scholtens, J.; Gill, D.; Christie, P. The COVID-19 pandemic, small-scale fisheries and coastal fishing communities. Coast. Manag. 2020, 48, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manlosa, A.O.; Hornidge, A.K.; Schlüter, A. Aquaculture-capture fisheries nexus under COVID-19: Impacts, diversity, and social-ecological resilience. Marit. Stud. 2021, 20, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.J.; Jakub, R.; Valdivia, A.; Setiawan, H.; Setiawan, A.; Cox, C.; Kiyo, A.; Darman; Djafar, L.F.; de la Rosa, E.; et al. Immediate impact of COVID-19 across tropical small-scale fishing communities. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 200, 105485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. The Hidden Harvest. The Global Contribution of Capture Fisheries. 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277664581_World_Bank_2012_The_Hidden_Harvest_The_global_contribution_of_capture_fisheries (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- FAO. Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles: Thailand. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/facp/tha?lang=en (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Panjarat, S. Sustainable Fisheries in the Andaman Sea Coast of Thailand. Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea Office of Legal Affairs; The United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chansang, H.; Poovachiranon, S. The distribution and species composition of seagrass beds along the Andaman Sea coast of Thailand. Phuket Mar. Biol. Cent. Res. Bull. 1994, 59, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Coulthard, S. Adapting to environmental change in artisanal fisheries—Insights from a South Indian Lagoon. Glob. Environ. Change Hum. Policy Dimen. 2008, 18, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschke, M.J.; Berkes, F. Exploring strategies that build livelihood resilience: A case from Cambodia. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jara, H.J.; Tam, J.; Reguero, B.G.; Ganoza, F.; Castillo, G.; Romero, C.Y.; Gévaudan, M.; Sánchez, A.A. Current and future socio-ecological vulnerability and adaptation of artisanal fisheries communities in Peru, the case of the Huaura province. Mar. Policy 2020, 119, 104003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S.; Gunderson, L.H. Resilience and adaptive cycles. In Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems; Gunderson, L.H., Holling, C.S., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 25–62. [Google Scholar]

- DFID. Sustainable Livelihoods; Guidance Sheets; Department for International Development: London, UK, 1999; pp. 1–10.

- Stognief, N.; Walk, P.; Schöttker, O.; Oei, P. Economic resilience of German lignite regions in transition. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mizutani, S.; Sasaki, T. Foundational research of education for community development to emphasize the forest-river-ocean nexus—Examination using an adaptive cycle model to evaluate resilience. Environ. Educ. 2018, 2018, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki, S. Disaster resilience in sustaining activities on fishers-based forest conservation initiatives: Focus on before and after the Great East Japan earthquake. J. Reg. Policy Stud. 2020, 12, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, S.; McNamara, N.; Acholo, M. Sustainable livelihood approach: A critical analysis of theory and practice. Geog. Pap. 2009, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Harohau, D.; Blythe, J.; Sheaves, M.; Diedrich, A. Limits of tilapia aquaculture for rural livelihoods in Solomon Islands. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JICA. A Book to Understand the Recent Trends of International Development Assistance. 2003; (In Japanese). Available online: https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/360/360/360_000_11743572.html (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Salik, K.M.; Jahangir, S.; Hasson, S. Climate change vulnerability and adaptation options for the coastal communities of Pakistan. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 112, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, R.; Arango, C.; Lomboy, C.G.; Box, S. Financial inclusion to build economic resilience in small-scale fisheries. Mar. Policy 2020, 118, 103982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinner, J.E.; Adger, W.N.; Allison, E.H.; Barnes, M.L.; Brown, K.; Cohen, P.J.; Gelcich, S.; Hicks, C.C.; Hughes, T.P.; Lau, J.; et al. Building adaptive capacity to climate change in tropical coastal communities. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cinner, J.E.; Barnes, M.L. Social dimensions of resilience in social-ecological systems. One Earth 2019, 1, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharifuzzaman, S.M.; Hossain, M.S.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Sarker, S.; Chowdhury, M.S.N.; Chowdhury, M.Z.R. Elements of fishing community resilience to climate change in the coastal zone of Bangladesh. J. Coast. Conserv. 2018, 22, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, H.R.; Lau, J.; Giordano, C.; Suri, S.K.; Advani, S.; Sharan, S. Preliminary lessons from COVID-19 disruptions of small-scale fishery supply chains. World Dev. 2021, 143, 105473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).