Abstract

Within the context of Instagram celebrity-based brand endorsement, this study investigates the effects of parasocial interaction, perceived ad message authenticity, and the match-up between brand and celebrity. An online survey was administered to 253 college students taking introductory advertising or PR courses. Respondents, in return, received course credits. As hypothesized, study results reveal that parasocial interaction positively influences perceived ad message authenticity, the match-up between brand and celebrity, and attitude toward ads. In addition, perceived ad message authenticity and the match-up between brand and celebrity have a positive impact on consumers’ attitudes toward ads. The current study provides advertising practitioners with implications when it comes to creating advertising campaign messages and selecting celebrity endorsers.

1. Introduction

Advertisers around the world employ celebrity endorsement for a number of reasons, including its positive impacts on increased attention to ads, attitude toward the brand, and purchase intention, not to mention the increased sales. The use of celebrity endorsement has long been prevalent in traditional media such as TV, newspapers, and magazines. However, with the decline in traditional media and the growth of digital media, celebrity endorsement has become ubiquitous on social media.

Social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram) is the tool that most celebrities use to connect with their fans. They connect through direct mails and real-time chatting and by posting updates and sharing photos and videos. In return, fans visit their favorite celebrities’ social media sites to keep themselves up to date on any news concerning those celebrities. In sum, social media plays a pivotal role in the communication between fans and celebrities.

Social media has, indeed, become a prominent platform on which to promote products and services via celebrity endorsement. Moreover, as with traditional media, the celebrities reap rewards. For instance, Cristiano Ronaldo, a professional soccer player, charges $1.6 million per post, and Ariana Grande, an American singer and actress, earns $1.51 million for each sponsored post, on their Instagram pages [1]. In terms of Twitter, Ronaldo charges $868,604 per post on his Twitter account, and the NBA superstar LeBron James charges $470,356 per Twitter post [2].

Social media has bolstered the relationship between celebrities and the number of their fans in the world and enriched fans’ emotional attachment and engagement with their celebrities. Some celebrities and fans can interact more frequently through social media, engaging in constant conversation. Celebrities often use social media not only for interacting with their fans but also for promoting their movies, concerts, charity events, or causes they support [3]. However, Cristiano Ronaldo, Ariana Grande, Kim Kardashian, and many others monetize their social media by endorsing products or brands. In light of such impacts on the relationship between consumers and celebrities, marketers see marketing opportunities in social media in the form of celebrity endorsement.

In spite of the prevalent use of celebrities’ endorsement in social media, little research has been conducted on how such endorsements work in these contexts. This study may provide unique contributions as it shows how Instagram celebrity-based brand endorsement works focusing on three factors: parasocial interaction, perceived ad message authenticity, and match-up between brand and celebrity. Thus, the current study delves into the effects of parasocial interaction, perceived ad message authenticity, and the match-up between brand and celebrity as it evaluates Instagram celebrity-based brand endorsements. These three factors were selected for the current study because of their importance in the celebrity endorsement literature.

Prior researchers have considered parasocial interaction to be an important factor in influencing the effects of celebrity endorsement. Parasocial interaction refers to a kind of psychological relationship experienced by an audience in their mediated encounters with performers in the mass media, particularly on television and on online platforms. As perceived authenticity is deemed to enhance message effectiveness and credibility [4,5], we include it as an important factor. Lastly, based on the match-up hypothesis, we assume that a match between a celebrity endorser and an endorsed brand will boost advertising effectiveness [6,7]. Given the importance of celebrity-based brand endorsement in social media, the results of this research should be of interest not only to scholars but also to marketing practitioners.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Parasocial Interaction with Celebrity

Horton and Wohl suggested that parasocial interaction or relationship takes place between media audiences and television performers when people are repeatedly exposed to media persona [8]. According to Horton and Wohl [8], parasocial interactions can be divided into three dimensions such as friendship, understanding, and identification. First, friendship refers to “a mutual relationship that is characterized by intimacy and liking” [9]. Second, understanding refers to “the degree to which a fan thinks that he or she knows the celebrity personally and profoundly” [9]. Third, identification refers to “a process of social influence through which an individual adopts attitudes or behaviors of another when there are clear benefits associated with such adoption” [9]. Social media could be considered to be the best media that could promote parasocial interaction between fans and their beloved celebrities.

In the context of celebrity endorsement, prior research found that parasocial relationships have a positive impact on consumers’ attitudes and their behaviors. For instance, in the political decision-making process, individuals who develop a parasocial relationship with a celebrity endorser have favorable attitudes toward the celebrity endorser and the endorsed political candidate [10]. In a similar vein, Kim, Ko, and Kim [11] found that consumers hold a positive attitude toward products and strong purchase intentions when parasocial relationships are found between consumers and celebrity endorsers. In addition, the parasocial relationship between consumers and TV shopping hosts leads to high levels of shopping satisfaction [12]. Thus, the following hypothesis is put forward:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Parasocial interaction will positively influence (a) perceived ad message authenticity, (b) match-up between brand and celebrity, and (c) attitude toward ads.

2.2. Perceived Ad Message Authenticity

In the advertising context, authentic advertising refers to “one that conveys the illusion of the reality of ordinary life in reference to a consumption situation” [13]. Similarly, Miller also defined ad authenticity as “the extent to which consumers perceive an ad is portraying the brand in a manner that resembles reality” [14]. Stern suggests that the successful creation of authentic advertising can be attributed to the rhetorical use of stories that resemble elements of real life [13]. In sum, consumers may perceive advertising to be authentic when they are ready to accept the illusion of mimetic.

Prior studies found that an ad’s authenticity plays an important role in positive effects on attitudes [13,15,16]. For instance, according to Schallehn, Burmann, and Riley [2], perceived authenticity increases consumer level of trust, resulting in a positive attitude toward the ads. Miller found that ad authenticity has a significant positive effect on attitudes toward ads and brands [14]. Similarly, Um’s study also showed that perceived ad authenticity is positively related to attitudes toward “femvertising” [10]. In the social media context, Pöyry, Pelkonen, Naumanen, and Laaksonen found that perceived authenticity of social media celebrities is positively related to the followers’ photo attitudes [16]. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Perceived ad message authenticity will positively influence attitudes toward ads.

2.3. Match-Up between Brand and Celebrity

In the celebrity endorsement context, the term “match-up” has been used interchangeably with “fit” and “congruence.” According to the match-up hypothesis, persuasion is enhanced when individuals perceive “fit” or “congruence” between the messenger and the message [17]. Based on the match-up hypothesis, Rossitier and Percy suggested that the visual imagery of an advertisement delivers information over and above the information in explicit verbal arguments [18].

Prior studies have found positive impacts on consumers’ attitudes and behaviors. For instance, Choi and Rifon [19] found that congruence between a celebrity and a product had a direct and positive impact on attitude toward ads. In one study, Pradhan, Duraipandian, and Sethi found that a match-up between brand personality and celebrity personality led to positive effects on brand attitude and purchase intention [20]. Other studies also support the notion that the effectiveness of celebrity endorsements rests on the fit between the celebrity endorser and the product [6,17,21]. Thus, the following hypothesis is put forth:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

A match-up between an endorsed brand and a celebrity endorser will positively influence attitudes toward ads.

3. Method

3.1. Design and Procedure

We chose Instagram as the social media platform in this study because many Korean celebrities use it to endorse brands [22]; moreover, among young college students (study participants), Instagram is the most popular social media platform [23]. For this study, a real celebrity (a Korean female singer in her 20s) was employed to enhance a sense of realism. An actual endorsement ad on Instagram by the celebrity was used as the stimulus.

Study participants taking introductory advertising or PR courses were first asked to read a consent form before commencing the online survey. Since it is difficult to recruit only fans of the selected celebrity, I chose a celebrity who is widely accepted and favored by college students. In addition, the level of parasocial interaction with the celebrity may play as a barometer to measure whether study participants are fans or not. By clicking the “Proceed” button on the bottom of the online survey, they understood that they were in effect agreeing to participate in this study. Questions that were first asked concerned participants’ daily social media visit frequency, daily usage time, social media activities, and use of Instagram. Before being exposed to the ads, participants answered a question regarding parasocial interaction with a celebrity endorser. Then, after viewing the ads, they were asked to respond to items measuring “match-up,” “authenticity,” and “attitude toward ads.” These items were borrowed from prior studies and proved their validity. The original questionnaire was drafted in English and then translated into Korean. The accuracy of the Korean version was verified via a back-translation procedure using external translators [24]. All measures used in this research are shown in Appendix A.

3.2. Participants and Data Collection

For this study, college students who were taking introductory advertising and public relations courses took the online survey and received course credits for completing the survey in return. A total of 253 respondents participated in the survey. Of these, 94.9% (n = 240) indicated that they visited social media sites at least once per day. Interestingly, 48.2% (n = 122) indicated that they visited social media sites more than 10 times per day. In terms of time spent visiting a social media site, 112 participants (44.3%) responded that they spent more than an hour per visit. Among the survey participants, 85.8% (n = 217) were likely to post to their social media daily or monthly while 14.2% (n = 36) would never post anything.

In regard to Instagram accounts, 94.1% (n = 238) possessed Instagram accounts, whereas only 5.9% (n = 15) did not. On average, participants owned approximately 3~4 social media accounts. The average age of survey respondents was 23.2 years old. Of this sample, males made up 35.6% (n = 90), and females made up 64.4% (n = 163). Juniors made up the largest portion (39.1%, n = 99); the rest were seniors (32.4%, n = 82), and sophomores (28.5%, n = 72).

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Parasocial Interaction

Parasocial interaction with a celebrity endorser was measured using five items based on a study about parasocial relationships with celebrities on social media [3]. Parasocial interaction was measured on a 7-point scale anchored with “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree.” Some items included (1) “I think I understand [celebrity’s name] quite well”, (2) “I would like to have a friendly chat with [celebrity’s name]”, and (3) “[Celebrity’s name] makes me feel comfortable, as if I were with a good friend”. The reliability for this scale was 0.82.

3.3.2. Perceived Ad Message Authenticity

Items used to measure the perceived ad message authenticity in this study were adopted from a study about authenticity in consumption [25]. To assess subjects’ perceived ad message authenticity, we used a 7-point scale with three items: “The ad message was authentic”, “The ad message was realistic”, and “The ad message was truthful”. The scale was anchored with “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree”. The reliability for this scale was 0.88.

3.3.3. Match-Up between Brand and Celebrity

To measure match-up between brand and celebrity, three items were borrowed from a study on definition, role, and measure of congruence [26]. The match-up between brand and celebrity was measured on a 7-point scale anchored with “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree.” Some items included (1) “This brand and [celebrity’s name] go well together”, (2) “This brand is well-matched with [celebrity’s name]”, and (3) “In my opinion, [celebrity’s name] is very appropriate for this brand”. The reliability for this scale was 0.93.

3.3.4. Attitude toward Ads

Using a seven-point semantic differential scale, this study measured attitude toward the ads with the following three items: “very bad/very good”, “very favorable/very unfavorable,” and “dislike very much/like very much”. The reliability for this scale was 0.92 [27].

4. Results

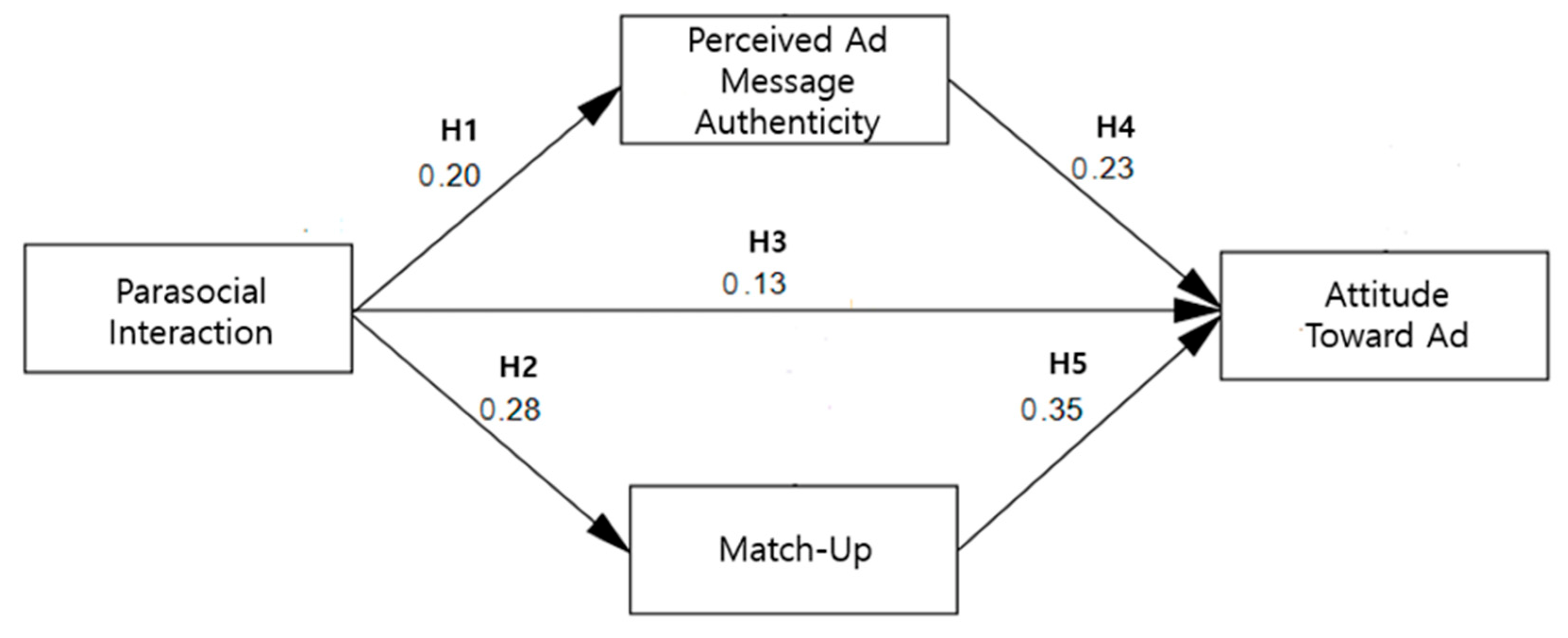

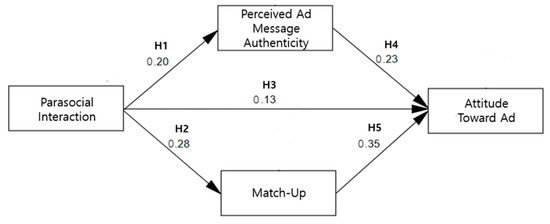

Output from the analysis revealed the composite reliability (CR), the average variance extracted (AVE), and the correlation coefficients between the constructs, which are summarized as in Table 1. To test the structural model concerning the relationships among the variables, the path analysis was performed via SPSS AMOS 21.0 [28]. Figure 1 shows the structural equation model for relationships of parasocial interaction to perceived ad message authenticity, match-up, and attitude toward ads. As shown in Table 2, the overall fit indices for the model were acceptable, revealing a moderate fit of the model to the data (x2 = 45.34, df = 1, p < 0.001; GFI = 0.93; AGFI = 0.89; NFI = 0.91; CFI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.06).

Table 1.

Composite reliability (CR), the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) (in bold) and correlations between constructs (off-diagonal).

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Model for Relationships of Parasocial Interaction to Perceived Ad Message Authenticity, Match-Up, and Attitude toward Ads. Goodness-of-fit statistics (x2 = 45.34, df = 1, p < 0.001; GFI = 0.93; AGFI = 0.89; NFI = 0.91; CFI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.06).

Table 2.

Parameter estimates for causal paths.

A model is regarded as acceptable if the normed fit index (NFI) and goodness of fit index (GFI) exceed 0.90 and the comparative fit index (CFI) exceeds 0.93, and when RMS is less than 0.08 [29,30]. Thus, the original model was rejected and the modification indices were examined as a way of improving the model fit [31].

In the current study, H1 posits that parasocial interaction will positively influence (a) perceived ad message authenticity, (b) match-up between brand and celebrity, and (c) attitude toward ads. The paths from parasocial interaction to perceived ad message authenticity, match-up between brand and celebrity, and attitude toward ads produced statistically significant standardized coefficients 0.20, 0.28, and 0.14 (p < 0.001), thus supporting H1a, H1b, and H1c.

H2 proposes that parasocial interaction will positively influence the perceived match-up between brand and celebrity. As expected, study results show that the path from perceived ad message authenticity to attitude toward ads produced statistically significant standardized coefficient 0.23 (p < 0.001), thus supporting H2.

Lastly, H3 states that match-up between an endorsed brand and a celebrity endorser will positively influence attitude toward ads. As shown in Table 2, the study results show that the path from match-up between brand and celebrity to attitude toward ads produced a statistically significant standardized coefficient of 0.35 (p < 0.001), thus supporting H3.

5. Discussion

Prior literature shows that parasocial interaction or relationship with a celebrity has a positive impact on attitude toward ads, endorsed brands, purchase intention, political candidates, and even social causes [10,11,12,32,33,34]. Study results suggest that, in a social media context (i.e., Instagram), parasocial interaction positively influenced perceived ad message authenticity, the match-up between brand and celebrity, and attitude toward ads. In a similar vein, Brown and Basil found that emotional involvement with Johnson through parasocial interaction affected the public’s perceptions of HIV-AIDS risk and high-risk behaviors [32]. The current study results provide advertising practitioners implications when it comes to choosing a celebrity endorser. One important criterion for increasing advertising effectiveness may be whether target audiences are in a parasocial relationship with a celebrity endorser.

Authenticity, or at least the perception of authenticity, has become an important concept in advertising. Advertisers pursue authentic advertising so as to gain consumer trust. Consumers, after all, are inundated with messages and have made themselves more conscious, and conscientious, of brands. For this very reason, Nike has consistently fought against many social issues that prohibit people from achieving their full potential. In the fall of 2018, for instance, Nike rolled out its “Believe in something even if it means sacrificing everything” campaign featuring the controversial NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick, which drew a great deal of attention. This study found that perceived ad message authenticity had a positive impact on attitude toward ads. Marketers tend to target Millennials (born 1981–1995) and Generation Z (born 1996–2005), as these constituents have strong spending power and seem more passionate about social causes than their older counterparts do. Similarly, in the tourism context, Ramkissoon and Uysal found a significant positive relationship between perceived authenticity and the cultural behavioral intentions of tourists [35].

In the fields of marketing, advertising, sponsorship, cause-related marketing, and others, scholars have given much attention to the concept of “match-up” [6,17,19,20,21]. As a general rule of thumb, a match-up or a fit is believed to have a positive impact on consumers’ attitudes and behaviors. Similar to prior studies, this study also found that a match-up between an endorsed brand and a celebrity endorser positively influenced attitudes toward ads. This study supports the idea that an important criterion in selecting a celebrity endorser is a match-up between a brand and a celebrity [36,37]. Similarly, Kamins and Gupta found that an increased congruence for the spokesperson/product combination resulted in the perception of higher believability and attractiveness of the spokesperson and a more favorable product attitude [38,39,40,41].

To date, companies have been using different social media to bolster their visibility and relationships with the public [42]. This study indicates that celebrity endorsement of consumer-brand engagement in Instagram works through parasocial interaction and perceived ad message authenticity and that the match-up between brand and celebrity increase consumers’ attitude toward ads. Similarly, Marques, Casais, and Camilleri found that a celebrity’s posts attracted more followers to the brand’s Instagram [43]. This study suggests that marketers can enhance consumer-brand engagement through social media and celebrity brand endorsement plays a pivotal role in consumer-brand engagement.

Like many other research, this study has certain limitations. First, this study limited its responses to students from a university. The study results would be different if the overall and/or an older population were included in the sample. To make the study results more representative and generalizable, it is essential to use the general population in future research. Second, instead of using a fictitious brand, this study used a real brand name to lend a sense of realism to the subjects participating in the study. However, the use of a real brand name could result in consumer bias in processing the ad message. For a future study, in order to control consumers’ preexisting biases toward a brand, it may be desirable to use a fictitious brand.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Hongik University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Composition of Questionnaire

| Factors | Abbreviation | Items Measurement | Sources |

| Parasocial Interaction | PI1 PI2 PI3 PI4 PI5 | I think I understand [celebrity’s name] quite well. I would like to have a friendly chat with [celebrity’s name] [Celebrity’s name] makes me feel comfortable, as if I were with a good friend. If [celebrity’s name] were not a celebrity, we would have been a good friend. [Celebrity’s name] seems to understand things I want to know. | Chung and Cho [3] Cronbach’s α = 0.82 |

| Perceived Ad Message Authenticity | PA1 PA2 PA3 | The ad message was authentic. The ad message was realistic. The ad message was truthful. | Beverland and Farrelly [25] Cronbach’s α = 0.88 |

| Match-Up | MU1 MU2 MU3 | This brand and [celebrity’s name] go well together. This brand is well matched with [celebrity’s name]. In my opinion, [celebrity’s name] is very appropriate for this brand. | Fleck and Quester [26] Cronbach’s α = 0.93 |

| Attitude toward Ads | AA1 AA2 AA3 | very bad/very good very favorable/very unfavorable dislike very much/like very much | MacKenzie and Lutz [27] Cronbach’s α = 0.92 |

References

- Sweney, M. Cristiano Ronaldo Shoots to Top of Instagram Rich List. The Guardian, 20 July 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/jun/30/cristiano-ronaldo-shoots-to-top-of-instagram-rich-list(accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Abhinandan, S. 5 Highest-Paid Athletes in the World for Twitter Posts, Read Details. The Youth, 7 August 2020. Available online: https://www.theyouth.in/2020/08/07/5-highest-paid-athletes-in-the-world-for-twitter-posts-read-details/(accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Kowalczyk, C.M.; Pounders, K.R. Transforming celebrities through social media: The role of authenticity and emotional attachment. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Kozinets, R.V.; Sherry, J.F., Jr. Teaching old brands new tricks: Retro branding and the revival of brand meaning. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molleda, J.C.; Roberts, M. The value of “authenticity” in “glocal” strategic communication: The new Juan Valdez campaign. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2008, 2, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, L.R.; Homer, P.M. Physical attractiveness of the celebrity endorser: A social adaptation perspective. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 11, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.S.; Roy, S.; Bailey, A.A. Exploring brand personality–celebrity endorser personality congruence in celebrity endorsements in the Indian context. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 1158–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, D.; Wohl, R.R. Mass communication and para-social interaction. Psychiatry 1956, 19, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Cho, H. Fostering parasocial relationships with celebrities on social media: Implications for celebrity endorsement. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, N.H. Effectiveness of celebrity endorsement of a political candidate among young voters. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2017, 45, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Ko, E.; Kim, J. SNS users’ para-social relationships with celebrities: Social media effects on purchase intentions. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2015, 25, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.M.; Kim, Y.K. Older consumers’ TV home shopping: Loneliness, parasocial interaction, and perceived convenience. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 763–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, B. Authenticity and the textual persona: Postmodern paradoxes in advertising narrative. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1994, 11, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, F.M. Ad authenticity: An alternative explanation of advertising’s effect on established brand attitudes. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2015, 36, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, E.; Peter, P.C. The real campaign: The role of authenticity in the effectiveness of advertising disclaimers in digitally enhanced images. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 77, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallehn, M.; Burmann, C.; Riley, N. Brand authenticity: Model development and empirical testing. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2014, 23, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamins, M.A. An investigation into the “match-up” hypothesis in celebrity advertising: When beauty may be only skin deep. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, J.R.; Percy, L. Attitude change through visual imagery in advertising. J. Advert. 1980, 9, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.M.; Rifon, N.J. It is a match: The impact of congruence between celebrity image and consumer ideal self on endorsement effectiveness. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, D.; Duraipandian, I.; Sethi, D. Celebrity endorsement: How celebrity–brand–user personality congruence affects brand attitude and purchase intention. J. Mark. Commun. 2016, 22, 456–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, B.D.; Busler, M. Matching products with endorsers: Attractiveness versus expertise. J. Consum. Mark. 1998, 15, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W. SNS Celebrity Endorsers. 2020. Available online: https://newsis.com/view/?id=NISX20200429_0001009781&cID=10401&pID=10400 (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Lee, B.R. Heavy Use of Social Media. 2021. Available online: http://www.seouleconews.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=63052 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Hui, C.H.; Triandis, H.C. Measurement in cross-cultural psychology: A review and comparison of strategies. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1985, 16, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M.B.; Farrelly, F.J. The quest for authenticity in consumption: Consumers’ purposive choice of authentic cues to shape experienced outcomes. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 36, 838–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, N.D.; Quester, P. Birds of a feather flock together… definition, role and measure of congruence: An application to sponsorship. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 975–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Lutz, R.J. An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, G.D. Path Analysis; Statistical Associates Publishing: Asheboro, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Testing for the factorial validity, replication, and invariance of a measurement instrument: A paradigmatic application based on the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1994, 29, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equations Models; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.J.; Basil, M.D. Media celebrities and public health: Responses to ‘Magic Johnson’s HIV disclosure and its impact on AIDS risk and high-risk behaviors. Health Commun. 1995, 7, 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R.B.; McHugh, M.P. Development of parasocial interaction relationships. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 1987, 31, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, L.I. Fostering consumer–brand relationships in social media environments: The role of parasocial interaction. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Uysal, M.S. The effects of perceived authenticity, information search behaviour, motivation and destination imagery on cultural behavioural intentions of tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.Z.; Baker, M.J. Towards a practitioner-based model of selecting celebrity endorsers. Int. J. Advert. 2000, 19, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.Z.; Baker, M.J.; Tagg, S. Selecting celebrity endorsers: The practitioner’s perspective. J. Advert. Res. 2001, 41, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamins, M.A.; Gupta, K. Congruence between spokesperson and product type: A matchup hypothesis perspective. Psychol. Mark. 1994, 11, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, B.D.; Busler, M. The match-up hypothesis: Physical attractiveness, expertise, and the role of fit on brand attitude, purchase intent and brand beliefs. J. Advert. 2000, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, N.H. What affects the effectiveness of celebrity endorsement? Impact of interplay among congruence, identification, and attribution. J. Mark. Commun. 2018, 24, 746–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.A. Reinvestigating the endorser by product matchup hypothesis in advertising. J. Advert. 2015, 45, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriotti, P.; Zeler, I.; Camilleri, M.A. Corporate communication through social networks: The identification of the key dimensions for dialogic communication. In Strategic Corporate Communication in the Digital Age; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, I.R.; Casais, B.; Camilleri, M.A. The Effect of Macrocelebrity and Microinfluencer Endorsements on Consumer–brand Engagement in Instagram. In Strategic Corporate Communication in the Digital Age; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).