The Influence of Higher Education on Student Learning and Agency for Sustainability Transition

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To investigate tertiary students’ sustainability perspectives in terms of their views, knowledge, and behaviour prior to a tertiary education intervention;

- To investigate the relationship between sustainability education in the tertiary curriculum and students’ sustainability perspectives, and identify the influences that moderate this relationship; and

- To investigate tertiary students’ experience of transformative learning in sustainability education and identify the conditions that facilitate this type of learning.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Environmental Behaviour and the VBN Model

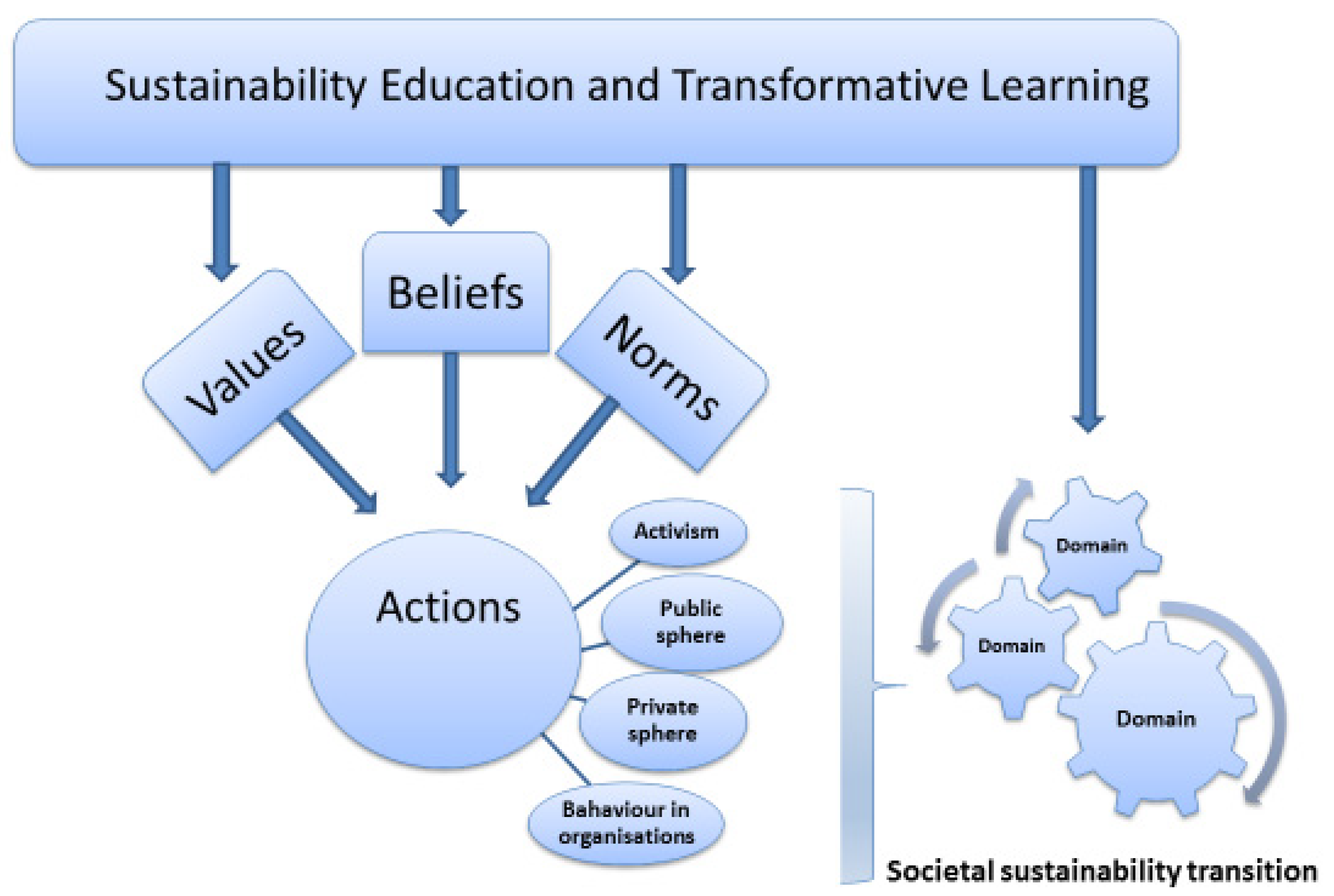

2.2. Sustainability Education and the Transformative Learning Model

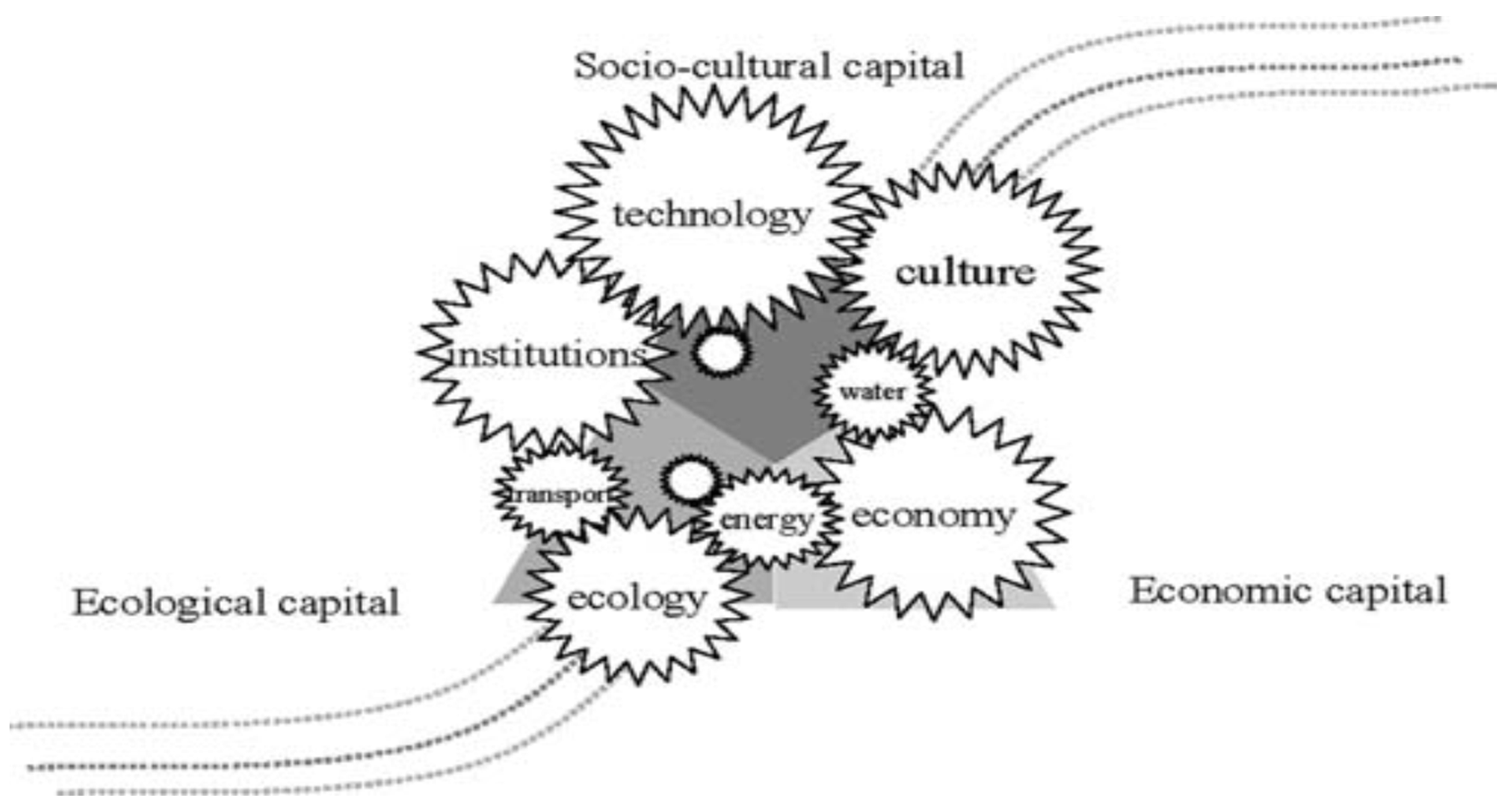

2.3. Sustainability Transitions and the Transition Management Model

2.4. Broad Conceptual Framework

- Learning can manifest in TL theory as instrumental, communicative, and transformative learning or even as resistance; in the VBN model, learning can result in a change in values, beliefs, norms, and behaviours; and in TM theory, learning features on multiple scales and includes individual learning, collaborative/social learning, and organisational learning.

- Resistance is evident in all three theories and can block or even reverse progress towards sustainability/transformation. In terms of individual learning, resistance can arise due to epistemic barriers, value orientations, or educational praxis; environmental behaviour can be blocked by attitudinal and situational/contextual factors; and resistance in socio-technical systems stems from established structures and existing power relations.

- Connection/synergy is a catalyst for change in all three theories: in TL theory, synergy is evident across aspects of a person’s lifeworld, between instrumental and communicative learning, between types of knowledge, and between cognitive, affective, and conative outcomes; in the VBN model, the synergistic effect of values, beliefs, norms, and situational/contextual factors can inhibit or promote action; and in TM theory, transformation is contingent on the connection/synergy between actors/agents in niches and between sectors/domains and levels in the societal system.

- Agency is a fundamental element in all three theories and is reflected in different levels of action. Agency may be an outcome of TL, is reflected in behaviour in the VBN, and is a key input to TM.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Paradigm

3.2. Research Method

3.3. Research Approach

- Study 1. Initial literature review (published in 2011, [105])

- Study 2. Pilot study (published in 2013—data 2012–2013, [106])

- Study 3. Case study (published in 2014—data 2005–2013, [107])

- Study 4. Multi-university study (published in 2018—data 2013–2015, [25])

- Study 5. Transformative learning study (published in 2021—data 2017, [108])

3.4. Research Instruments

3.5. Research Analysis

3.6. Research Conducted in the Component Studies

4. Results in Component Studies

4.1. Study 1. Initial Literature Review

4.2. Study 2. Pilot Study (Published 2013—Data 2012–2013)

4.3. Study 3. Case Study (Published 2014—Data 2005–2013)

4.3.1. Incremental Inclusion of Sustainability Topics

4.3.2. Introductory EfS Seminar

4.3.3. Sustainability Topics and Assessment

4.4. Study 4. Multi-University Study (Published 2018—Data 2013–2015)

4.4.1. Cross-Sectional Analysis

- Gender had no effect on the importance of sustainability, HWN, or INS scores but a pervasive effect on mean NEP (females M = 3.68, SD = 0.53, n = 607 compared to males M = 3.48, SD = 0.53, n = 345, F (1951) = 31.22, p = 0.000) and average HUMAN orientation scores (females M = 3.22, SD = 0.81 compared to males M = 2.89, SD = 1.78, F (1951) = 36.85, p = 0.000). This result was detected across age (except under 18 years of age) and discipline groups (except science), and there was no difference in gender across culture.

- Age group was significant, with all scores increasing with age except for average NEP, which exhibited a U-shaped, “early adult dip”, similar to the pilot EfS study.

- Culture (home region) exerted a significant influence on all scores except HWN, with NEP scores for Anglo-Saxon, EU, and Latin American students higher than Asian and Indian subcontinental counterparts (Welch adjusted statistic F (779.43) = 26.822, p = 0.000), similar to the pilot EfS study.

- Discipline of study influenced the importance of sustainability and HWN (not INS), with NEP scores for students in Arts, Science, and Education programmes higher than Accounting, Business Management, Architecture, and Engineering students (Welch adjusted statistic F (4168.06) = 26.57, p = 0.000). Thus, discipline of study and cultural factors remained significant influences on the importance of sustainability and on INS, HWN, and NEP scores, similar to the pilot EfS study.

4.4.2. Longitudinal Analysis

4.5. Study 5. Transformative Learning Study (Published 2021—Data 2017)

4.5.1. Incidence of PT/TL

4.5.2. Contribution/Importance of Mezirow’s 10 Steps to PT/TL

4.5.3. Factors Influencing PT/TL

4.5.4. Type of Learning Outcomes

4.5.5. Development of Competency, Agency, and Advocacy for Sustainability

5. Discussion

5.1. Challenges to Implementing SE in HE (Context of Contexts)

5.2. Challenges in the Learning Context (Motivation and Resistance)

5.3. Learning Outcomes from SE in HE (Mixed Effects/Converging Views)

5.4. Holistic Sustainability as a Challenging Concept (Crossing the Liminal Threshold)

5.5. SE in the Context of a Total Learning System (Connecting the Dots)

5.6. SE Effects on Personal Behaviour and Agency (Limited Spheres of Influence)

5.7. Developing Sustainability Competencies (Leveraging Wider Transformation)

5.8. Maintaining Optimism for Societal Change (Problematise vs. Opportunitise)

5.9. Free-Choice Learning and Agency in ST (Cascade of Chasms)

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goyal, N.; Howlett, M. Who learns what in sustainability transitions? Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 34, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R.; Ceulemans, K.; Alonso-Almeida, M.; Huisingh, D.; Lozano, F.J.; Waas, T.; Lambrechts, W.; Lukman, R.; Hugé, J. A review of commitment and implementation of sustainable development in higher education: Results from a worldwide survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, W.; Clugston, R.M. International efforts to promote higher education for sustainable development. Plan. High. Educ. 2003, 31, 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, I. Post-sustainability and environmental education: Remaking the future for education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 24, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E. Sustainability in higher education in the context of the UN DESD: A review of learning and institutionalization processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Shaping The Future We Want: UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005–2015) Final Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Leihy, P.; Salazar, J. Education for sustainability in university curricula: Policies and practice in Victoria. In Centre for the Study of Higher Education; University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2011; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts, W.; Mulà, I.; Ceulemans, K.; Molderez, I.; Gaeremynck, V. The integration of competences for sustainable development in higher education: An analysis of bachelor programs in management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiropoulos, E. The Contribution of Tertiary Sustainability Education to Student Knowledge, Views, Attitudes and Behaviour toward Sustainability. Ph.D. Thesis, Victoria University, Melbourne, Ausrtalia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Keynan, A.; Assaraf, O.B.Z.; Goldman, D. The repertory grid as a tool for evaluating the development of students’ ecological system thinking abilities. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2014, 41, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remingtondoucette, S.M.; Musgrove, S.L. Variation in sustainability competency development according to age, gender, and disciplinary affiliation. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 537–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.; Rodela, R. Social learning towards sustainability: Problematic, perspectives and promise. NJAS—Wagening J. Life Sci. 2014, 69, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Mannke, F. Addressing The Use of Non-Traditional Methods of Environmental Education: Achieving the Greatest Environmental and Educational Benefit for The European Region. In Addressing Global Environmental Security through Innovative Educational Curricula; Allen-Gil, S., Stelljes, L., Borysova, O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kopnina, H. Education for sustainable development (ESD): The turn away from ‘environment’ in environmental education? Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, E. Transformative Learning: Educational Vision for the 21st Century; Zed Books: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Living in the Earth:Towards an Education for Our Time. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 4, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano García, F.J.; Kevany, K.; Huisingh, D. Sustainability in higher education: What is happening? J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 757–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, L.V.; Filho, W.L.; Brandli, L.; Macgregor, C.J.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Ozuyar, P.; Moreira, R. Barriers to innovation and sustainability at universities around the world. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 1268–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Wu, Y.-C.J.; Brandli, L.L.; Avila, L.V.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Caeiro, S.; Madruga, L.R.D.R.G. Identifying and overcoming obstacles to the implementation of sustainable development at universities. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2017, 14, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, T.; Harraway, J.; Lovelock, B.; Skeaff, S.; Slooten, L.; Strack, M.; Shephard, K.; Slooten, E. Multinomial-Regression Modeling of the Environmental Attitudes of Higher Education Students Based on the Revised New Ecological Paradigm Scale. J. Environ. Educ. 2013, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shephard, K.; Harraway, J.; Jowett, T.; Lovelock, B.; Skeaff, S.; Slooten, L.; Strack, M.; Furnari, M. Longitudinal analysis of the environmental attitudes of university students. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 21, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiropoulos, E. The personal context of student learning for sustainability: Results of a multi-university research study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teisl, M.F.; Anderson, M.W.; Noblet, C.L.; Criner, G.K.; Rubin, J.; Dalton, T. Are Environmental Professors Unbalanced? Evidence From the Field. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 42, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Mukute, M.; Chikunda, C.; Baloi, A.; Pesanayi, T. Transgressing the norm: Transformative agency in community-based learning for sustainability in southern African contexts. Int. Rev. Educ. 2017, 63, 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J.; Sterling, S.; Goodson, I. Transformative Learning for a Sustainable Future: An Exploration of Pedagogies for Change at an Alternative College. Sustainability 2013, 5, 5347–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. High. Educ. 1996, 32, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, C.; Chabay, I.; Collins, K.; Gutscher, H.; Lotz-Sisitka, H.; McCauley, S.; Niles, D.; Pfeiffer, E.; Ritz, C.; Schmidt, F. Knowledge, Learning, and Societal Change: Finding Paths to a Sustainable Future. 2011. Available online: http://www.sustainabilogy.eu/wp-publications/chris_blackmore_knowledge_2011/ (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Wals, A.E.; Kronlid, D.; McGarry, D. Transformative, transgressive social learning: Rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 16, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative learning: Theory to practice. In Transformative Learning in Action: No. 74. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education; Cranton, P., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997; Volume 74, pp. 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C. New Environmental Theories: Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Rotmans, J. Managing Transitions for Sustainable Development. In Understanding Industrial Transformation: Views from Different Disciplines; Olsthoorn, X., Wieczorek, A.J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Rotmans, J.; Kemp, R. Managing Societal Transitions: Dilemmas and Uncertainties: The Dutch Energy Case-Study. In OECD Workshop on the Benefits of Climate Policy: Improving Information for Policy Makers; OECD: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Neumayer, E. Weak versus Strong Sustainability: Exploring the Limits of Two Opposing Paradigms; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.J. Learning Our Way to Sustainability. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 5, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiropoulos, L. Navigating the Journey to Sustainability: The Case for Embedding Sustainability Literacy Into All Tertiary Education Business Programs. Int. J. Environ. Cult. Econ. Soc. Sustain. Annu. Rev. 2011, 7, 247–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, W.E.; Beckmann, S.C.; Lewis, A.; van Dam, Y. A Multinational Examination of the Role of the Dominant Social Paradigm in Environmental Attitudes of University Students. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawcroft, L.J.; Milfont, T.L. The use (and abuse) of the new environmental paradigm scale over the last 30 years: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtel, R.B.; Corral-Verdugo, V.; Asai, M.; Riesle, A.G. A cross-cultural study of environmental belief structures in USA, Japan, Mexico, and Peru. Int. J. Psychol. 2006, 41, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Armendáriz, L.I. The “New Environmental Paradigm” in a Mexican Community. J. Environ. Educ. 2000, 31, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Carrus, G.; Bonnes, M.; Moser, G.; Sinha, J.B. Environmental beliefs and endorsement of sustainable development principles in water conservation toward a new human interdependence paradigm scale. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 703–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervisoglu, S. University students’ value orientations towards living species. Hacet. Univ. J. Educ. 2010, 39, 132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Erdoğan, N. Testing the new ecological paradigm scale: Turkish case. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2009, 4, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.D.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, G.T.; Stern, P.C. Environmental Problems and Human Behavior; Allyn & Bacon: Needham Heights, MA, USA, 1996; p. 369. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Educating for a sustainable future: A transdisciplinary vision for concerted action. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Environment and Society: Education and Public Awareness for Sustainability, Thessaloniki, Greece, 8–12 December 1997; UNESCO: Thessaloniki, Greece, 1997; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- De Corte, E. Historical developments in the understanding of learning. In The Nature of Learning. Using Research to Inspire Practice; OECD: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 35–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, H.; Istance, D.; Benavides, F. The Nature of Learning: Using Research to Inspire Practice; OECD Pub. Centre for Educational Research and Innovation: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann, R. “Sustainability Learning”: An Introduction to the Concept and Its Motivational Aspects. Sustainability 2010, 2, 2873–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddewela, E.; Warin, C.; Hesselden, F.; Coslet, A. Embedding responsible management education—Staff, student and institutional perspectives. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J.B. From Theory to Practice: A Cognitive Systems Approach. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 1993, 12, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kember, D.; Hong, C.; Yau, V.W.K.; Ho, S.A. Mechanisms for promoting the development of cognitive, social and affective graduate attributes. High. Educ. 2016, 74, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, D. A Connected Curriculum for Higher Education; UCL Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hiser, K.K. Sustainability: Perspectives of Students as Stakeholders in the Curriculum; University of Hawaii: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Istance, D.; Dumont, H. Future directions for learning environments in the 21st century. In The Nature of Learning: Using Research to Inspire Practice; OECD: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 317–340. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, J.; Cotton, D. Making the hidden curriculum visible: Sustainability literacy in higher education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for People and Planet: Creating Sustainable Futures for All; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber, A.; van Mierlo, B.; Grin, J.; Leeuwis, C. The practical value of theory: Conceptualising learning in the pursuit of a sustainable development. In Social Learning Towards a Sustainable World; Wals, A.E.J., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, A.; Nikel, J. Differentiating and Evaluating Conceptions and Examples of Participation in Environment-Related Learning. In Participation and Learning: Perspectives on Education and the Environment, Health and Sustainability; Reid, A., Jensen, B.B., Nikel, J., Simovska, V., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 32–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts, W.; Van Petegem, P. The interrelations between competences for sustainable development and research competences. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 776–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. Whole Systems Thinking as a Basis For Paradigm Change in Education: Explorations in the Context of Sustainability. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bath, Bath, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shephard, K.; Mann, S.; Smith, N.; Deaker, L. Benchmarking the environmental values and attitudes of students in New Zealand’s post-compulsory education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atherton, J. Resistance to learning: A discussion based on participants in in-service professional training programmes. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 1999, 51, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meyer, J.; Land, R. Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge: Linkages to ways of thinking and practising within the disciplines. In Improving Student Learning: Improving Student Learning Theory and Practice—Ten Years on; Rust, C., Ed.; Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Benn, S.; Bubna-Litic, D. Is the MBA sustainable? In Teaching Business Sustainability. Volume 1: From Theory to Practice; Galea, C., Roberts, S., Eds.; Greenleaf Publications: Sheffield, UK, 2004; pp. 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, E.W.; Snyder, M.J. A critical review of research on transformative learning theory, 2006–2010. In The Handbook of Transformative Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice; Taylor, E.W., Cranton, P., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, J.; Barton, G.; Allison, J.; Cotton, D. Learning Development and Education for Sustainability: What are the links? J. Learn. Dev. High. Educ. 2015, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.W. Transformative Learning Theory. In Transformative Learning Meets Bildung: An International Exchange; Laros, A., Fuhr, T., Taylor, E.W., Eds.; SensePublishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Transformative learning and sustainability: Sketching the conceptual ground. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. 2011, 5, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Understanding Transformation Theory. Adult Educ. Q. 1994, 44, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. An overview on transformative learning. In Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning Theorists… in Their Own Words; Illeris, K., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sipos, Y.; Battisti, B.; Grimm, K. Achieving transformative sustainability learning: Engaging head, hands and heart. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, E.A. Transforming Transformative Education Through Ontologies of Relationality. J. Transform. Educ. 2018, 16, 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S.; Dawson, J.; Warwick, P. Transforming Sustainability Education at the Creative Edge of the Mainstream: A Case Study of Schumacher College. J. Transform. Educ. 2018, 16, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, H. Thematic Analysis: Transformative Sustainability Education. J. Transform. Educ. 2018, 16, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnlaugson, O. Metatheoretical Prospects for the Field of Transformative Learning. J. Transform. Educ. 2008, 6, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cranton, P.; Taylor, E.W. Transformative learning theory: Seeking a more unified theory. In The Handbook of Transformative Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice; Taylor, E.W., Cranton, P., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Learning to think like an adult: Core Concepts of Transformation Theory. In Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress; Mezirow, J., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Learning to think like an adult: Core Concepts of Transformation Theory. In The Handbook of Transformative Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice; Taylor, E.W., Cranton, P., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 73–95. [Google Scholar]

- King, K.P. Facilitating perspective transformation in adult education programs: A tool for educators. In Pennsylvania Adult & Continuing Education Research Conference; King, K.P., Ferro, T.R., Eds.; Widener University: Chester, PA, USA, 1998; pp. 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- King, K.P. The Handbook of the Evolving Research of Transformative Learning Based on the Learning Activities Survey; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, S.E. Measuring the Importance of Precursor Steps to Transformative Learning. Adult Educ. Q. 2009, 60, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.A.; Duerden, M.D.; Duffy, L.N.; Hill, B.J.; Witesman, E.M. Measurement of transformative learning in study abroad: An application of the learning activities survey. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 21, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagl, S. Theoretical foundations of learning processes for sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2007, 14, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.; Kern, F.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A. A Research Agenda for the Sustainability Transitions Research Network. Sustainability Transitions Research Network (STRN); Sustainable Consumption Institute, University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, R.; Loorbach, D.; Rotmans, J. Transition management as a model for managing processes of co-evolution towards sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2007, 14, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Stirling, A.; Berkhout, F. The governance of sustainable socio-technical transitions. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1491–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Ontologies, socio-technical transitions (to sustainability), and the multi-level perspective. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Grin, J.; Pel, B.; Jhagroe, S. The politics of sustainability transitions. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2016, 18, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Rotmans, J. A dynamic conceptualization of power for sustainability research. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers, P.J.; Mierlo, B.; Hoes, A.-C. Toward an Integrative Perspective on Social Learning in System Innovation Initiatives. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoes, A.-C.; Beers, P.J.; van Mierlo, B. Communicating tensions among incumbents about system innovation in the Dutch dairy sector. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2016, 21, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, J.; Beers, P.; Wals, A.E. Social learning in regional innovation networks: Trust, commitment and reframing as emergent properties of interaction. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 49, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Hanson, W.E.; Clark Plano, V.L.; Morales, A. Qualitative Research Designs: Selection and Implementation. Couns. Psychol. 2007, 35, 236–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Sharrock, W. The Philosophy of Social Science Research, 3rd ed.; Pearson Longman: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A. Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckler, A.; McLeroy, K.; Goodman, R.M.; Bird, S.T.; McCormick, L. Toward Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: An Introduction. Health Educ. Q. 1992, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiropoulos, L. The Role of Heis in Society’s Transformation to Sustainability: The Case for Embedding Sustainability Concepts in Business Programs; RMIT University: Melbourne, Australia; Victoria University: Footscray, Australia; University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sidiropoulos, L.; Wex, I.; Sibley, J. Supporting the Sustainability Journey of Tertiary International Students in Australia. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2013, 29, 52–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiropoulos, E. Education for sustainability in business education programs: A question of value. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 85, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiropoulos, E. Measuring transformative learning for sustainability in higher education: Application of an augmented Learning Activities Survey. In Handbook on Teaching and Learning for Sustainable Development; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-environmental Behaviour: The role of values, situational factors and goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turaga, R.M.R.; Howarth, R.B.; Borsuk, M.E. Pro-environmental behavior. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1185, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, P.W. Inclusion with Nature: The Psychology Of Human-Nature Relations. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Schmuck, P., Schultz, W.P., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew, M.J.; Hoggan, C.; Rockenbach, A.N.; Lo, M.A. The Association Between Worldview Climate Dimensions and College Students’ Perceptions of Transformational Learning. J. High. Educ. 2016, 87, 674–700. [Google Scholar]

- El-Deghaidy, H. Education for Sustainable Development: Experiences from Action Research with Science Teachers. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2012, 3, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Noy, S.; Patrick, R.; Capetola, T.; McBurnie, J. Inspiration From the Classroom: A Mixed Method Case Study of Interdisciplinary Sustainability Learning in Higher Education. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2017, 33, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C. How development leads to democracy: What we know about modernization. Foreign Aff. 2009, 88, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C. The WVS Cultural Map of the World. In World Values Survey: Findings & Insights; Institute for Comparative Survey Research: Vienna, Austria, 2010; Available online: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs/articles/folder_published/article_base_54 (accessed on 24 September 2010).

- Puybaraud, M. Generation Y and the Workplace. Annual Report 2010; Johnson Controls: London, UK, 2010; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Saijo, T. Reexamining the relations between socio-demographic characteristics and individual environmental concern: Evidence from Shanghai data. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, D. Illiberal Education: The Politics of Race and Sex on Campus; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. The learning of ecology, or the ecology of learning. In Key Issues in Sustainable Development and Learning: A Critical Review; Gough, W.S.S., Ed.; Routledge Falmer: London, UK, 2004; pp. 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The dynamics of innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, S.; Scott, W. Higher Education and Sustainable Development: Paradox and Possibility; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, J.; Thomas, I.; Wilson, A. Education for Sustainability in Australian Universities: Where Is the Action? Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2006, 22, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Balas, D.; Adachi, J.; Banas, S.; Davidson, C.; Hoshikoshi, A.; Mishra, A.; Motodoa, Y.; Onga, M.; Ostwald, M. An international comparative analysis of sustainability transformation across seven universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezbatchenko, A.W. Sustainability in Colleges and Universities: Toward Institutional Culture Shifts. J. Stud. Aff. N. Y. Univ. 2010, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- McGaw, N.; Gentile, M.C. Integrating Sustainability into Management Education: A Status Report; The Aspen Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Aspen Institute. Where Will They Lead? MBA Student Attitudes about Business and Society; The Aspen Institute Center for Business Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Net Impact, New Leaders, New Perspectives: A Survey of MBA Student Opinions on the Relationship between Business and Social/Environmental Issues. 2009. Available online: http://www.netimpact.org/displaycommon.cfm?an=1&subarticlenbr=2581#mba (accessed on 1 June 2010).

- Impact Net. Undergraduate Perspectives: The Business of Changing the World. 2010. Available online: http://www.netimpact.org/associations/4342/files/Undergraduate_Perspectives_2010_final.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2010).

- Felgendreher, S.; Löfgren, Å. Higher education for sustainability: Can education affect moral perceptions? Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, S.-Y.; Jackson, N.L. Influence of an Environmental Studies Course on Attitudes of Undergraduates at an Engineering University. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 45, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, K. Deep learning and education for sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2003, 4, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggan, C. A typology of transformation: Reviewing the transformative learning literature. Stud. Educ. Adults 2016, 48, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Future-oriented higher education: Which key competencies should be fostered through university teaching and learning? Futures 2012, 44, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, C.; Ferreira, J.-A.; Blomfield, J. Teaching sustainable development in higher education: Building critical, reflective thinkers through an interdisciplinary approach. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsoom, Q.; Khanam, A. Inquiry into sustainability issues by preservice teachers: A pedagogy to enhance sustainability consciousness. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.K. Undergraduates in a Sustainability Semester: Models of social change for sustainability. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 47, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, E.A. Transformative and Restorative Learning: A Vital Dialectic for Sustainable Societies. Adult Educ. Q. 2004, 54, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J. Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.B.; Schwartz, S. Values. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Social Behaviour and Applications; Berry, J., Segall, M.H., Kagicibasi, C., Eds.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1997; Volume 3, pp. 77–118. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, I.; Saito, O.; Vaughter, P.; Whereat, J.; Kanie, N.; Takemoto, K. Higher education for sustainable development: Actioning the global goals in policy, curriculum and practice. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 14, 1621–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shephard, K. Higher Education’s Role in “Education for Sustainability”. Aust. Univ. Rev. 2010, 52, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S.; Witham, H. Pushing the boundaries: The work of the Higher Education Academy’s ESD Project1. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, R.; Glavič, P. What are the key elements of a sustainable university? Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2007, 9, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapitulčinová, D.; AtKisson, A.; Perdue, J.; Will, M. Towards integrated sustainability in higher education—Mapping the use of the Accelerator toolset in all dimensions of university practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4367–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D.; Schott, C. Academic Agency and Leadership in Tourism Higher Education. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2013, 13, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, G.; Dyer, M. Strategic leadership for sustainability by higher education: The American College & University Presidents’ Climate Commitment. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.; Tilbury, D.; Sharp, L.; Deane, E. Turnaround Leadership for Sustainability in Higher Education Institutions; Office for Learning and Teaching, Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education: Sydney, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, N.; Stevenson, R.B.; Lasen, M.; Ferreira, J.-A.; Davis, J. Approaches to embedding sustainability in teacher education: A synthesis of the literature. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 63, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, S.; Hegarty, K. From praxis to delivery: A Higher Education Learning Design Framework (HELD). J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 122, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Christ, G.; Sterling, S.; van Dam-Mieras, R.; Adomßent, M.; Fischer, D.; Rieckmann, M. The role of campus, curriculum, and community in higher education for sustainable development—A conference report. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinakou, E.; Pauw, J.B.-D.; Goossens, M.; Van Petegem, P. Academics in the field of Education for Sustainable Development: Their conceptions of sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiró, P.S.; Neutzling, D.M.; Lessa, B.D.S. Education for sustainability in higher education institutions: A multi-perspective proposal with a focus on management education. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thürer, M.; Tomašević, I.; Stevenson, M.; Qu, T.; Huisingh, D. A systematic review of the literature on integrating sustainability into engineering curricula. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulà, I.; Tilbury, D.; Ryan, A.; Mader, M.; Dlouhá, J.; Mader, C.; Benayas, J.; Dlouhý, J.; Alba, D. Catalysing Change in Higher Education for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 798–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, M.; Makrakis, V.; Concina, E.; Frate, S. Educating academic staff to reorient curricula in ESD. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Heidt, T.; Lamberton, G. How Academics in Undergraduate Business Programs at an Australian University View Sustainability. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 30, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, C.R.; Hewege, C. Integrating sustainability education into international marketing curricula. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P. Integrating sustainable development into economics curriculum: A case study analysis and sector wide survey of barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 209, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, B.A.; Miller, K.K.; Cooke, R.; White, J.G. Environmental sustainability in higher education: How do academics teach? Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 19, 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, N.E.; Ohsowski, B. Content trends in sustainable business education: An analysis of introductory courses in the USA. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Bornasal, F.; Brooks, S.; Martin, J.P. Civil Engineering Faculty Incorporation of Sustainability in Courses and Relation to Sustainability Beliefs. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2015, 141, C4014005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.; Cotton, D. Times of change: Shifting pedagogy and curricula for future sustainability. In The Sustainable University: Progress and Prospects; Sterling, S., Maxey, L., Luna, H., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 151–167. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton, D.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A. Energy saving on campus: A comparison of students’ attitudes and reported behaviours in the UK and Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harring, N.; Lundholm, C.; Torbjörnsson, T. The Effects of Higher Education in Economics, Law and Political Science on Perceptions of Responsibility and Sustainability. In Handbook of Theory and Practice of Sustainable Development in Higher Education; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunbode, C.A. The NEP scale: Measuring ecological attitudes/worldviews in an African context. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 1477–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rideout, B.E. The liberal arts and environmental awareness: Exploring endorsement of an environmental worldview in college students. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2014, 9, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sammalisto, K.; Sundström, A.; von Haartman, R.; Holm, T.; Yao, Z. Learning about Sustainability—What Influences Students’ Self-Perceived Sustainability Actions after Undergraduate Education? Sustainability 2016, 8, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glisczinski, D.J. Transformative higher education: A meaningful degree of understanding. J. Transform. Educ. 2007, 5, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackintosh, L.; Karol, E. Analysing the Lack of Student Engagement in the Sustainability Agenda: A Case Study in Teaching Architecture. Int. J. Learn. Annu. Rev. 2011, 17, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Levesque, V.R.; Salvia, A.L.; Paço, A.; Fritzen, B.; Frankenberger, F.; Damke, L.I.; Brandli, L.L.; Ávila, L.V.; Mifsud, M.; et al. University teaching staff and sustainable development: An assessment of competences. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 16, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, K.; Thomas, I.; Kriewaldt, C.; Holdsworth, S.; Bekessy, S. Insights into the value of a ‘stand-alone’ course for sustainability education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2011, 17, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, H.L. Learning sustainability leadership: An action research study of a graduate leadership course. Int. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 2016, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaim, J.A.; Maloni, M.J.; Napshin, S.A.; Henley, A.B. Influences on Student Intention and Behavior Toward Environmental Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethic. 2013, 124, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.; von der Heidt, T. Business as Usual? Barriers to Education for Sustainability in the Tourism Curriculum. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2013, 13, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesala-Varttala, T.; Humala, I.; Isacsson, A.; Salonen, A.; Nyberg, C. Fostering Sustainability Competencies and Ethical Thinking in Higher Education: Case Sustainable Chocolate. eSignals Res. 2021. Available online: https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe202201051276 (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- von der Heidt, T.; Lamberton, G. Sustainability in the undergraduate and postgraduate business curriculum of a regional university: A critical perspective. J. Manag. Organ. 2011, 17, 670–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jänicke, M. Ecological modernisation: New perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D. To transition! Governance panarchy in the new transformation. In Inaugural Address; Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W.; McMeekin, A.; Mylan, J.; Southerton, D. A critical appraisal of Sustainable Consumption and Production research: The reformist, revolutionary and reconfiguration positions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 34, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, E.; O’Neil, J. Introduction to Special Issue on Transformative Sustainability Education. J. Transform. Educ. 2018, 16, 275–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, D.; Kagawa, F. Teetering on the Brink: Subversive and Restorative Learning in Times of Climate Turmoil and Disaster. J. Transform. Educ. 2018, 16, 302–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Selby, D.; Sterling, S.R. Sustainability Education: Perspectives and Practice across Higher Education; Earthscan: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; p. 364. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.; Blewitt, J. Third wave sustainability in higher education: Some (inter) national trends and developments. In Sustainability Education: Perspectives and Practice across Higher Education; Sterling, S., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Levintova, E.M.; Mueller, D.W. Sustainability: Teaching an Interdisciplinary Threshold Concept through Traditional Lecture and Active Learning. Can. J. Sch. Teach. Learn. 2015, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Paas, F.; Renkl, A.; Sweller, J. Cognitive Load Theory and Instructional Design: Recent Developments. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 38, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Merriënboer, J.J.G.; Kester, L.; Paas, F. Teaching complex rather than simple tasks: Balancing intrinsic and germane load to enhance transfer of learning. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2006, 20, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Michelsen, G. Learning for change: An educational contribution to sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 8, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blewitt, J. The Ecology of Learning: Sustainability, Lifelong Learning And Everyday Life; Earthscan: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 1–241. [Google Scholar]

- Trencher, G.; Vincent, S.; Bahr, K.; Kudo, S.; Markham, K.; Yamanaka, Y. Evaluating core competencies development in sustainability and environmental master’s programs: An empirical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Rieckmann, M. Introduction to the Routledge Handbook of Higher Education for Sustainable Development. In Routledge Handbook of Higher Education for Sustainable Development; Barth, M., Michelsen, G., Rieckmann, M., Thomas, I., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Innovative Learning Environments; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chiong, K.S.; Mohamad, Z.F.; Abdul Aziz, A.R. Factors encouraging sustainability integration into institutions of higher education. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 14, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.; Gram-Hanssen, I.; O’Brien, K. Teaching the “how” of transformation. Sustain. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Vargas, V.R.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlacek, S. The role of universities in fostering sustainable development at the regional level. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, R. Entwining a Conceptual Framework: Transformative, Buddhist and Indigenous-Community Learning. J. Transform. Educ. 2018, 16, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebert, K. Effective Sustainability Education Is Political Education. Educ. J. Res. Debate 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D.; Miller, W.; Winter, J.; Bailey, I.; Sterling, S. Knowledge, agency and collective action as barriers to energy-saving behaviour. Local Environ. 2015, 21, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şebnem Feriver, G.; Teksöz, R.O.; Alan, R. Training early childhood teachers for sustainability: Towards a ‘learning experience of a different kind’. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 717–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibbel, A. Pathways towards sustainability through higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2009, 10, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, N.; Gifford, R.; Milfont, T.L.; Weeks, A.; Arnocky, S. Learned helplessness moderates the relationship between environmental concern and behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 55, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D.R.E.; Miller, W.; Winter, J.; Bailey, I.; Sterling, S. Developing students’ energy literacy in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 456–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hursh, D.; Henderson, J.; Greenwood, D. Environmental education in a neoliberal climate. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, F.; Davison, A.; Wood, G.; Williams, S.; Towle, N. Four Impediments to Embedding Education for Sustainability in Higher Education. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 31, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, J.K. Transformative Sustainability Learning Within a Material-Discursive Ontology. J. Transform. Educ. 2018, 16, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L. Transformative Sustainability Education and Empowerment Practice on Indigenous Lands: Part One. J. Transform. Educ. 2018, 16, 344–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springett, D. ‘Education for sustainability’ in the business studies curriculum: A call for a critical agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2005, 14, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akenji, L. Consumer scapegoatism and limits to green consumerism. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015; Available online: https://www.gcedclearinghouse.org/resources/unesco-global-action-programme-education-sustainable-development-information-folder (accessed on 1 March 2021).

| Stage 1. Research Conducted at One University (Australia) | |

|---|---|

| Study 1. Initial literature review study (published in 2011) | |

| Scope/Aims | To provide a broad perspective on the influence of higher education (HE) on student learning for sustainability (LfS) in the context of personal and societal change; describe how complex societal systems transform; discuss the influence of the business sector and HE; and focus on the influence of tertiary business schools in facilitating the sustainability transition (ST) process. |

| Method | Secondary data research combined theoretical streams in psychology, social psychology, education and learning, and societal transformation to connect the field of adult LfS in HE with individual transformation and social change. Explored the contribution of the HE and business sectors in sustainability transitions. Outlined key conceptions of sustainability, different types of learning and pedagogical approaches, and explored the role and progress of personal and cultural values for sustainability around the world. Explored the role of values and pedagogy in learning for sustainability and the role and progress of tertiary business education in the sustainability transition process. In addition, linked the role of tertiary business education in fostering individual LfS and agency to facilitate societal transformation and argued for the inclusion of sustainability in all tertiary business education programmes. |

| Study 2. Pilot study (published 2013—data 2012–2013) | |

| Scope/Aims | To investigate the existing sustainability perspectives (views, knowledge, and attitudes) of international students at an Australian university and compare the influence of different SE pedagogical initiatives on their perspectives. |

| Method | Action research study was conducted at two campuses over two semesters in 2011. The sustainability interventions consisted of course-specific introductory sustainability seminars, courses with sustainability elements already embedded in course curricula, and courses with no elements of sustainability. The sample consisted of several thousand international students enrolled in undergraduate or postgraduate IT or business programmes or in English language courses. Changes in student’s sustainability perspectives were assessed using pre-post surveys based on NEP and open questions. A total of 267 completed surveys (hard copy) were analysed quantitatively and qualitatively to explore students’ initial sustainability perceptions and evaluate changes over time. Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS and included descriptive and inferential statistics, such as t-tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA), Cronbach’s alpha, and chi-square tests. |

| Study 3. Case study (published 2014—data 2005–2013) | |

| Scope/Aims | To describe the researcher’s pedagogical approach of using values to lever the inclusion of sustainability education (SE) in the curriculum of various business courses at an Australian university and investigate the immediate and medium-term impacts of various SE interventions on tertiary student views, attitudes, and behaviour towards sustainability |

| Method | Provided a detailed account of the researcher’s SE praxis in tertiary business education over an 8-year period (2005–2013), including examples of different interpretations of “value” to embed sustainability concepts into business courses. Reported the influence of an escalating integration of SE interventions on tertiary students’ sustainability views, conceptions, and behaviour over this time. Sample consisted of several thousand international and domestic students enrolled in business units taught or coordinated by the researcher. Research data were a synthesis of empirical results from online surveys in Study 2 (pilot study), course feedback and class discussions, as well as initial online survey results from Study 4 (multi-university study). |

| Stage 2. Research Conducted at Several Universities (Australia, Malaysia, Italy) | |

| Study 4. Multi-university study (published 2018—data 2013–2015) | |

| Scope/Aims | To use a common instrument to explore the sustainability perspectives of tertiary students across disciplines and levels of study in Australia, Italy, and Malaysia; investigate tertiary students’ prior knowledge, perceptions of the importance of sustainability and graduate skills required, and their awareness of campus sustainability activities; compare the influence of SE and regular education on tertiary student views, attitudes, and behaviour towards sustainability. |

| Method | Sample consisted of undergraduate and postgraduate students enrolled in a range of courses, disciplines, and locations at nine HEIs located in Australia, Malaysia, and Italy. A quasi-experimental design was adopted to collect data from EfS participants and non-EfS participants at each location with convenience sampling providing a wide representation of courses, disciplines, and locations. The sample covered several disciplines (engineering, architecture, business, sports medicine, health, biological sciences, education, etc.), modes of study (on-campus, distance education, and mixed mode), locations, and types of SE. Pre-post surveys were developed by a consensus of staff at participating universities and consisted of several scales and open-ended questions of student perceptions of graduate attributes, importance of sustainability, and their knowledge, views, attitudes, and behaviour towards sustainability. This included measures of environmental worldviews, such as the Inclusion of Nature in Self scale (INS), the NEP scale to measure beliefs and, the Hierarchy with Nature (HWN) scale to explore attitudes (developed by the researcher), ten items for self-reported behaviour, and measures of perceived importance of sustainability. Empirical data were collected online over five separate terms/semesters in 2013–2015. Several thousand students participated in the study and provided a total of 1422 completed responses. The dataset was analysed using SPSS and included descriptive and inferential statistics, such as t-tests, ANOVA, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), and Cronbach’s alpha as well as non-parametric tests and partial correlations. Cross-sectional data were analysed to investigate differences in student dispositions at one point in time, and longitudinal data (matched responses) were analysed to investigate changes in student dispositions and behaviour over the term. |

| Stage 3 Research Conducted at Two Universities (Australia) | |

| Study 5. Transformative learning study (published 2021—data 2017) | |

| Scope/Aims | To explore the incidence and experience of transformative learning (TL) for tertiary students in dedicated SE units at two Australian universities by applying an augmented LAS to determine: (a) the incidence of perspective transformation (PT)/TL, (b) the contribution and importance of Mezirow’s 10 steps towards TL, (c) the influence of demographic, academic, study-related, and situational factors on PT/TL, (d) the type of learning outcomes, and (e) the development of competence, personal agency, and advocacy for sustainability. |

| Method | Sample consisted of undergraduate students undertaking dedicated SE units at two universities in Australia (one rural, one urban). The SE units were compulsory for students enrolled in sustainability or environmental science majors in one university and for students in business courses in the other university. Both units were delivered in a blended on-campus/distance learning mode and also widely available as electives to students in other courses, which drew students from across diverse locations, disciplines, and motivations. An online post-course survey (concurrent mixed-methods approach) covered sustainability worldviews, knowledge and behaviour, cognitive shifts in attitudes and learning, the Learning Activities Survey (LAS) and supplementary questions to explore the incidence/type of student TL, the influence of background and contextual factors, perceived capability, and intended behaviour towards sustainability. Approximately 1000 students were invited and provided 301 useable responses. Survey data were analysed to assess changes in sustainability dispositions and the incidence and extent of TL. Quantitative data were analysed with SPSS and included descriptive and inferential statistics, such as t-tests, ANOVA and Cronbach’s alpha (for respondent’s LAS score of TL), non-parametric tests, and partial correlations. Qualitative data were analysed for deeper insights to complement findings from quantitative analysis. |

| Group | Cronbach’s Alpha (NEP) | Average NEP | LTG Limits | AA Dominance | BN Balance | AE Constraints | Eco-Crisis | INS | HWN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean 1 (std deviation) (p-value) 2 | mean 1 (std deviation) (p-value) 2 | mean 1 (std deviation) (p-value) 2 | mean 1 (std deviation) (p-value) 2 | mean 1 (std deviation) (p-value) 2 | mean 1 (std deviation) (p-value) 2 | mean 1 (std deviation) (p-value) 2 | mean 1 (std deviation) (p-value) 2 | ||

| Pre-test Control | 0.766 | 3.56 (0.519) | 3.14 (0.719) | 3.72 (0.901) | 3.78 (0.668) | 3.46 (0.704) | 3.69 (0.779) | 4.57 (1.446) | 2.21 (0.781) |

| Pre-test Intervention | 0.798 | 3.76 **a (0.546) (p < 0.0005) | 3.44 **a (0.854) (p < 0.0005) | 3.91 *a (0.809) (p = 0.033) | 3.97 **a (0.705) (p = 0.007) | 3.53 (0.742) | 3.97 **a (0.753) (p < 0.0005) | 4.71 (1.530) | 2.31 (0.744) |

| Post-test Control | 0.784 | 3.54 (0.539) | 3.11 (0.741) | 3.70 (0.857) | 3.76 (0.682) | 3.40 (0.726) | 3.72 (0.771) | 4.47 (1.475) | 2.24 (0.796) |

| Post-test Intervention | 0.806 | 3.78 **b (0.551) (p < 0.0005) | 3.51 **b (0.763) (p < 0.0005) | 3.86 (0.846) | 3.97 **b (0.638) (p = 0.002) | 3.57 *b (0.718) (p = 0.020) | 3.99 **b (0.749) (p = 0.001) | 4.93 **b (1.488) (p = 0.003) | 2.28 (0.761) |

| Control | No significant changes in any pre- and post-test NEP score | ||||||||

| Intervention | No significant changes in any pre- and post-test NEP, only for INS | ||||||||

| Phase/PT Precursor Step | Total Responses (n) | Share of Total Respondents % (n = 301) | Number (n) and Share (%) of Overall PT/TL Respondents 1 (n = 171) | Chi-Square 2 (Yates Correction) | p3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a Disorienting Dilemma (actions) | 112 | 37.2 | 80 (46.8) | 14.600 | <0.001 ** |

| 1b Disorienting Dilemma (social roles) | 124 | 41.2 | 94 (55.0) | 29.709 | <0.001 ** |

| 2a Self-examination (questioned worldviews) | 61 | 20.3 | 46 (26.9) | 9.856 | 0.002 ** |

| 2b Self-examination (maintained worldviews) | 82 | 27.2 | 54 (31.6) | 3.267 | 0.071 |

| 3 Critical reflection on assumptions | 55 | 18.3 | 45 (26.3) | 15.928 | <0.001 ** |

| 4 Recognised discontent shared | 89 | 29.6 | 68 (39.8) | 18.655 | <0.001 ** |

| 5 Explored new roles | 93 | 30.9 | 70 (40.9) | 17.615 | <0.001 ** |

| 6 Planned a course of action | 92 | 30.6 | 63 (36.8) | 6.682 | 0.010 * |

| 7 Acquired knowledge/skills | 79 | 26.2 | 65 (38.0) | 26.925 | <0.001 ** |

| 8 Tried on new roles | 67 | 22.3 | 52 (30.4) | 14.128 | <0.001 ** |

| 9 Built competence/confidence | 93 | 30.9 | 66 (38.6) | 10.174 | 0.001 ** |

| 10 Reintegrated into life | 78 | 25.9 | 64 (37.4) | 25.966 | <0.001 ** |

| None of these steps | 12.3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sidiropoulos, E. The Influence of Higher Education on Student Learning and Agency for Sustainability Transition. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053098

Sidiropoulos E. The Influence of Higher Education on Student Learning and Agency for Sustainability Transition. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):3098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053098

Chicago/Turabian StyleSidiropoulos, Elizabeth. 2022. "The Influence of Higher Education on Student Learning and Agency for Sustainability Transition" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 3098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053098

APA StyleSidiropoulos, E. (2022). The Influence of Higher Education on Student Learning and Agency for Sustainability Transition. Sustainability, 14(5), 3098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053098