Abstract

Crop diversity contributes to yield stability and nutrition security and is valued for its potential use in breeding improved varieties and adaptation to future climates. Women across the globe contribute to biodiversity conservation, and, in the Central Andes region, the cradle of potato diversity, rural women play a vital role in the management of a wealth of native potato diversity. To examine how gender roles and traditions influence the agricultural and conservation practices of male and female custodians of native potato diversity, we undertook a qualitative study in eight farming communities high in the Andes, in the Pasco region of Peru. This article reviews agricultural and crop diversity management practices, farmer motivations for conserving potato diversity, the role that agrobiodiversity plays in family diets and economies, and support of in situ conservation by external actors. It examines how gender norms limit the potential of women to fully benefit from the crop and argues for more gender-responsive approaches that empower both women and men, enable women to overcome barriers, and contribute to a more inclusive, community-based management of agrobiodiversity that ensures its long-term conservation and contribution to community development and well-being.

1. Introduction

Crop diversity is the foundation of sustainability, resilience, and food and nutrition security, and conserving it is an active and purposeful part of smallholder farming [1,2]. A decade ago, de Boef and colleagues [3](p. 791) affirmed that “Agrobiodiversity is a dynamic and constantly changing patchwork of relations between people, plants, animals, other organisms and the environment.” This is evident in the high Andes of Peru, where potato is the most important food crop, playing a pivotal role in the local food system and the lives of men and women [4,5]. Potato farming and conservation of the crop’s diversity have cultural significance in the complex social fabric of the high Andes, governed by tradition and influencing gender roles and norms, as men and women have differentiated roles and responsibilities in cultivation and conservation [5,6,7]. As is commonly the case in developing and emerging countries, women’s engagement in agriculture in Peru is characterized by gaps in access to assets and resources, which increases their vulnerability and affects their agricultural productivity [8,9].

This article describes the importance of potato in its center of origin and the ways in which management of the crop’s diversity is linked to gender roles and norms. While there has been significant progress in understanding the dynamics of biodiversity management and the role of local knowledge, there are still major gaps in understanding how gender norms and roles influence and are affected by in situ conservation, and how approaches can be enhanced or adjusted for the benefit of both conservation and gender equality. In an effort to fill the knowledge gap, we have sought to shed light on the following issues: (i) what are the traditional roles men and women play in native potato cultivation and conservation; (ii) how do their motivations for conservation and the challenges and opportunities they face differ; and (iii) how are these gender dynamics changing and what is the potential for generating more gender-equitable benefits from native potato diversity? Based on these insights, this paper argues for the design of gender-responsive and transformative interventions that can strengthen in situ conservation and contribute to women’s empowerment and gender equality.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Potato Biodiversity

The potato is the third most important food crop globally, cultivated and consumed on six continents, but it has special significance in the western half of South America, where it has played an important role in the history, culture, and identity of indigenous peoples [10,11,12]. The first potatoes were domesticated in that region 8,000 to 10,000 years ago, and the Central Andes region holds the world’s greatest potato biodiversity [10,13]. Following the Spanish conquest of South America in the 16th century, potatoes were slowly disseminated across Europe, North America, Asia, and Africa as farmers and crop breeders adapted them to local environments [10,13,14]. However, farmers in western South America continued to cultivate and consume a rich varietal diversity of native potatoes, conserving and renewing that agrobiodiversity through seed selection and exchange [7,10,15,16].

In spite of the establishment of breeding programs and many high yielding varieties being released since the 1950s, an estimated 2,800 to 3,300 native potato varieties are grown in the region, and nowhere is that genetic diversity as high as in Peru [14,17,18]. That diversity is the product of a dynamic process in which different relationships between people, plants, and the environment converge [6,16]. Native potato diversity contributes to community resilience, being a key source of food security and one of the resources farmers use to respond to and recover from disturbances [19,20,21]. It has also contributed to the food security of smallholder farmers outside the Andean region as potato breeders have used that genetic resource to develop more robust varieties for cultivation across the globe [10,14,22,23]. While breeding programs have primarily used native potatoes in the development of modern varieties, the International Potato Center (CIP) increased iron levels by 29% and zinc levels by 26% in a population of native potatoes with potential candidates for release as varieties in Peru, and which breeders in other regions are using to develop locally adapted varieties, as part of a global effort to reduce malnutrition [22].

Samples of native potato biodiversity are safeguarded in genebanks, but in situ conservation is also essential because it comprises genetic diversity that may not be represented in genebanks [19,24]. While enabling farmers to benefit from the food and nutrition security and resilience that native potato diversity provides, in situ conservation permits the continuing evolution of native cultivars as they adapt to changing pest, disease, and climate scenarios [1,10,19,25].

Potato is Peru’s second most important crop, representing 25% of agriculture’s contribution to the GDP, or 1.8% of the GDP, and grown on more than 700,000 farms distributed across most of the country’s regions, though primarily in the Andean highlands [26,27].

Most farmers grow higher-yielding modern, improved varieties, but native potatoes remain an important staple, especially for indigenous smallholders, many of whom plant both native and improved varieties [10,16,23]. According to a national assessment of potato cultivation in Peru in 2013, 39% of the country’s potato farmland was planted with native potatoes [28].

While native potatoes were almost exclusively consumed in the rural highlands two decades ago, the International Potato Center (CIP) has worked with an array of partners to raise awareness of their attributes in Peru’s largest cities, catalyzing demand and the development of varied value chains [29]. This resulted in a 70% increase in sales of native potatoes between 1998 and 2011 and a 49% increase in the price of native potatoes between 2007 and 2017, primarily thanks to urban and export markets, and farmers who supply those markets receive considerably higher prices than those who sell locally [29,30].

Andean farmers tend to sow dozens of native potato landraces in one plot—a mixture called chaqru or huachuy in Quechua—a practice that contributes to potato diversity conservation [10,17]. Farmers who conserve high levels of potato diversity are known as potato custodians, or custodians [19,31,32,33]. One study of the farms of 38 custodians in Peru’s Huancavelica region identified a total of 557 unique native cultivars [23]. This remarkable level of agrobiodiversity conservation is the result of traditional knowledge and reflects Andean farmers’ historic relationship with the crop and the environment [15]. Their traditional knowledge is empirical and is maintained by an intergenerational dynamism that follows differentiated patterns based on gender roles and norms [15,34].

Men and women who conserve high potato diversity reap multiple and differentiated benefits, which include more nutritious diets—since cultivars have varied protein, vitamin, iron, and zinc content—and resilience because they have varied levels of tolerance of abiotic and biotic stressors [1,17,20,21,25]. Native potatoes are also linked to sustainable land-use practices, with lower risk of erosion due to long fallows and the use of Andean foot plows, both of which sustain soil fertility and minimize erosion in fields with inclines of over 45%, traditions such as communal property, and a cosmovision that places the potato within a harmonious natural system [6,35,36]. Native potatoes are grown at high elevations, with the greatest diversity found between 3,900 and 4,200 m above sea level, and research shows that farmers have moved their potato fields 475 to 500 m higher over the past four decades [17].

Given the value of native potato biodiversity, national and international organizations have supported custodians by helping them organize themselves, and undertaken interventions to strengthen their in situ conservation [20,24,31]. These processes are helping to empower farmers, increasing awareness of their rights, and facilitating more informed decision-making processes regarding the management of their crop diversity and opportunities to alleviate poverty [32,37].

One result of such efforts was the creation of the Asociación de Guardianes de Papa Nativa del Centro de Peru (AGUAPAN), or Association of Native Potato Custodians of Central Peru, a farmer-governed organization that represents custodians from 77 communities in eight regions of Peru [32,33]. Each AGUAPAN member represents a different community and grows from 50 to 300 native potato cultivars [31,33]. AGUAPAN’s activities, which are supported by two Dutch potato seed companies, CIP, and other non-profit organizations, aim to strengthen community management of potato biodiversity, enhance the social capital that results from its conservation, and recognize the rights of custodian farmers as stipulated by clause 9 of the International Treaty for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture [32,33].

2.2. Gender and Potato Farming

Women play a central role in native potato management, as they do in the conservation of biodiversity across the globe, both to ensure the long-term availability of resources that they and their families use for subsistence and because of associated cultural and spiritual values [38]. Andean women lead different aspects of native potato cultivation, especially the management of the seed system, which, in the case of native potatoes, is almost exclusively informal. Women are responsible for variety as well as seed selection and storage and make decisions in households regarding the use of native potatoes, such as how many of which ones should be saved for seed, sold, or stored for home consumption, all of which affects in situ conservation [5,7,15].

These farmer-managed, informal seed systems are pivotal for the conservation of native potato diversity and contribute to increased resilience of the potato crop in the high Andes [39]. Because of the critical role women have in the management of potato seeds, Tapia and de la Torre [7] argued that “it would be justified calling women conservationists of native Andean seeds.”

Andean women have been acknowledged as possessing superior knowledge of native potato plants and tubers to men, who may defer to women when questions arise about identification [15]. Recent research suggests that women could also be superior potato farmers as a study of native potato variety repatriation from the CIP genebank to communities in the Peruvian Andes found that the survival rate of the repatriated varieties grown by women was higher than that of men or people younger than 29 [40]. Women also play a vital role in the transmission of knowledge and skills to the next generation regarding native potato management [5,7].

Nevertheless, rural women in Peru face challenges that are common to women across the Global South, such as less access to land, resources, and opportunities than men, as well as limited access to non-tangible assets, such as social capital and decision-making power, which limits their agency in agriculture and other spheres [8,9].

Despite the fact that both men and women play essential roles as food producers and agrobiodiversity custodians, women face more barriers [41]. Based on government statistics, Tafur et al. found that the average farm size of women was 1.8 hectares, whereas the average size of men’s farms was 3 hectares [41]. Women farmers within male-headed households tend to be invisible in statistics, which can reduce their access to agricultural services. An example of this is that only 9.5% of women farmers (65,000) received agricultural extension training in 2012, compared to 16.3% of men (254,000) [41]. In a study of the associativity of farmers in 17 Andean departments of Peru, Patel-Campillo and Salas determined that the Ministry of Agriculture’s strategic plan failed to recognize the heterogeneity of farmers, which placed women farmers at a disadvantage [42]. Within this structure, women custodians face varied challenges in achieving the necessary agency to overcome barriers and reap all the potential benefits of their involvement in native potato cultivation and conservation [43].

2.3. Pathways to Women’s Empowerment in Biodiversity Conservation Processes

Multiple factors influence the pathways to women’s empowerment in agriculture. Systemic barriers and patriarchal social norms still limit women from achieving their full potential. To understand the role and potential contribution of agricultural biodiversity to women’s empowerment, this paper uses the Social Relations Framework to analyze the underlying causes of gender inequality [44] in the context of potato biodiversity conservation experiences. The use of the framework focuses on five key elements of analysis: agency in decision-making, access to resources, gender division of labor, social norms, and recognition [39,45,46].

Women’s agency in decision-making is a fundamental step towards empowerment and is expressed through influence and action over key decisions that affect women’s lives [47,48]. Within the context of agrobiodiversity conservation, the focus is on decisions to conserve or not and what to conserve [46]. It also relates to specific choices, analyzing what, why, when, and how women and men decide to conserve biodiversity, specific crops, varieties or types of seeds, and how these choices and decisions affect their lives [49].

While decisions and choices constitute an important element in the analysis of pathways to empowerment, these choices and decisions are often strongly influenced by access to and control over resources, including natural resources, land, capital, markets, and labor [50,51]. In the context of biodiversity conservation, natural resources and land are very closely related. Resources can be managed individually, as common property or through open access, and, because women are less likely to own land, they rely more heavily on common property or open access resources [52]. Agency in choice and decision-making about what species, crops, or varieties to conserve are, therefore, highly dependent on resources.

Women and men’s knowledge, use, and conservation of biodiversity resources are highly variable and strongly influenced by social norms and gender division of labor. Society assigns different roles to women and men according to their rules and sanctions. These gender differences vary from one society to another and extend to agricultural production, linking social norms, division of labor, and decision-making [53].

One important element in the pathway to empowerment is recognition, which is regarded as a vital human need [54]. Recognition is a concept linked both to norms and psychological dimensions [55]. In the context of crop biodiversity conservation efforts, there are at least two levels of recognition at interplay. On one hand, the global recognition of the role of indigenous people and, particularly, women’s active contribution can have implications for the policies and design of future interventions [19,56]. On the other hand, elements of recognition at the local and individual level can have both psychological implications for the individuals and also reinforcing or transformative effects on social norms.

Considering the different elements of the Social Relations Framework described above, and their potential connection to crop biodiversity conservation, it becomes increasingly important to analyze their manifestation at the local level and their potential contributions to women’s empowerment. Examples of such contributions were documented in the long-term action research initiative in Southwest China coordinated by Song and Vernooy, which enhanced women’s participation in seed systems and thereby improved the wellbeing of rural households, particularly female-headed households [57]. Examples in Latin America include a project led by Chile’s Asociación Nacional de Mujeres Rurales e Indígenas (ANAMURI), or National Association of Rural and Indigenous Women, which organized custodians to grow agrobiodiversity in family gardens and disseminate seeds through exchanges, which helped the participants to resolve their daily needs and build economic autonomy [58]. Papa Andina, a regional initiative in South America that connected farmers to new market chains for native potatoes, empowered women farmers in Peru to achieve greater access to credit, land, and other resources [5]. In the cases mentioned above, we see clear connections of interventions that fostered a change in specific practices and thereby generated positive effects on the livelihood strategies of women.

Gender is a key consideration for equitable and effective biodiversity conservation practice [59]. Likewise, gender and cultural considerations are essential for the design and implementation of projects and policies to foster biodiversity conservation, development, and food systems transformation [4,9]. Incorporating gender considerations into governmental and non-governmental efforts to conserve biodiversity is key to achieving more significant and equitable outcomes [59]. By identifying and understanding how the different elements of the Social Relations Framework function in communities that manage native potato biodiversity, this study seeks to contribute to adjustments in local development approaches and inform the design of future interventions that (i) enhance community biodiversity management, (ii) facilitate women’s empowerment, and (iii) contribute to gender equality.

3. Materials and Methods

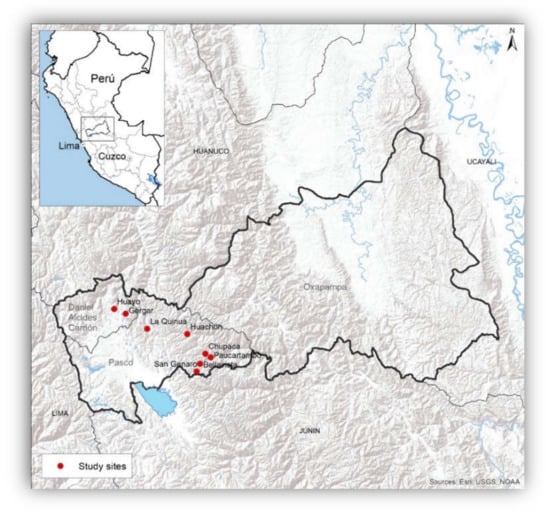

To gain insight into community management of native potato biodiversity in Peru, how gender norms and relations affect women’s participation in that management, and the implications of changing gender roles and other social dynamics, a qualitative study was carried out in eight farming communities in Peru’s Central Andes (Figure 1). The study followed a constructivist epistemology to overcome systemic or cultural bias embedded in the empirical research methods [60], and an interpretivist paradigm to capture the subjective experiences of people in their construction of reality [61]. One of the most valuable contributions of constructivism in this case is that it embraces a plurality of perspectives [62] that facilitate analysis of the multiple drivers of biodiversity conservation, its benefits, and potential outcomes.

Figure 1.

Locations of communities where research was undertaken.

The communities that were part of the study were selected because they are located within an agrobiodiversity hot spot, in an area with a concentration of AGUAPAN members, who conserve high levels of native potato diversity and maintain significant traditional knowledge. They are located in an area where women custodians are relatively active within AGUAPAN, among them the association’s vice president. Seven of the study participants are members of AGUAPAN, whereas four are closely related to AGUAPAN members.

The communities studied are clustered in the western highlands of Pasco department—a region that covers 25,028 km2 extending from the high Andes eastward into the upper Amazon Basin [63]. They are located in the provinces of Pasco and Daniel Alcides Carrion, near the regional capital of Cerro de Pasco, an historic mining city 4,330 m above sea level [64]. Despite the fortunes that have been extracted from Pasco’s mines, it is one of Peru’s poorest regions, where one out of four families lacks access to basic services and the average rate of population growth between 2010 and 2020 was negative (−0.3%) due mainly to migration to the Peruvian capital of Lima and other cities [63].

Data Generation and Analysis

Fieldwork was carried out in the communities between August 2019 and February 2020 using qualitative methods of inquiry to understand the local context, traditions, and gender dynamics. Before research activities began, a process of prior and informed consent was undertaken in which the study’s method and objectives were explained to participating farmers, and they were ensured that the information they provided would be gathered and administered in accordance with their wishes. Participants agreed that their information could be recorded and published in various formats or media, including an open-access journal. Gender, as a primary cultural frame for coordinating behavior and organizing social relations [65], was used to organize and analyze information. The study follows the Social Relations Framework, which argues that underlying causes of gender inequality are not confined to the household and family but are reproduced across a range of institutions, including community, state, and market [44]. This framework was used to analyze recognition, gender division of labor, gender norms and dynamics at the household, community, and institutional (AGUAPAN) level. The research was of an exploratory nature, which facilitated gathering pertinent information quickly from farmers, and the use of participatory tools to structure, stimulate, and visualize discussions [66,67,68]. A non-probability convenience sampling was used in order to achieve a gender balance among key informants [69].

Research began with a focus group in the community of Paucartambo, Pasco, with nine potato custodians. However, because women were reluctant to speak in the focus group, the research approach was subsequently changed to a combination of in-depth interviews and participant observation of men and women in their fields and homes, which included interaction and unstructured interviews. This methodology was chosen to better understand farmers’ lives and experience their native potato farming and conservation activities [70,71].

In-depth interviews were conducted with 11 farmers between the ages of 25 and 78. Using a gender responsive seasonal calendar tool, men and women farmers explained the agricultural activities they engage in over the course of the year to grow native potatoes, and how they divide or share those tasks between genders [66,67]. This tool enabled us to identify the distribution of responsibilities based on gender roles within a productive unit, in this case, a family [66,67]. Beginning in March of 2020, travel was severely restricted in Peru in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which made it impossible for researchers to return to the communities. In order to clarify statements by some farmers regarding native potatoes’ role within their cosmovision, semi-structured follow-up interviews were conducted with six of the farmers via telephone, or with the help of allies who live in the area.

A total of 17 interviews were conducted. Interviews and focus group discussions were recorded and transcribed (in Spanish). The names of all farmers were replaced with aliases. Data were processed using the Nvivo with open coding [72].

4. Results

Some of the farmers interviewed live only with a spouse, child, or parent, whereas others are members of households that comprise three generations. Their education levels range from incomplete primary school to the completion of secondary or vocational studies.

All the farmers grow a mix of native potato varieties known as chaqru, or huachuy. They explained that they grow native potatoes primarily for home consumption, and that they cultivate them in high areas above their communities, primarily on communal land but also on private land or rented plots.

As the potato custodian Bruno observed: “We grow huachuy (native potatoes) because for us, it’s like bread; it’s what sustains us through the year, from August (harvest) to August.”

Ana, a young mother and potato custodian who lives and farms with her parents, also reflected on the importance of native potatoes: “In my family, we plant (native potatoes) because we need the potato. It is one of the principal foods on the planet and it is nutritious for little children and adults as well. That’s why, as long as I can remember, I’ve planted them with my parents, because they say a lunch without potato isn’t lunch. It is a necessary part of any meal.”

Custodians explained that they inherited most of the native potato cultivars they grow from their parents, although they increase their potato diversity by obtaining new ones in varied ways. Both men and women obtain new native varieties at agrobiodiversity fairs or AGUAPAN meetings, where they may buy them or exchange one cultivar for another. Women primarily exchange potatoes locally or at fairs or meetings, but men also acquire new varieties in the potatoes they sometimes receive as payment for their work or other services. More men than women spoke of working at other farms, a reflection of the gender division of labor and the greater mobility that men enjoy as a result of social norms. This gives men more opportunities to expand the diversity of their native potato portfolios, whereas women are usually limited to accessing potato diversity and seeds through local exchange.

4.1. Farming

Farmers use a traditional, soil-conserving, minimal-tillage method of cultivating native potatoes, called chiwi or chiwa in Quechua, that is appropriate for sloping areas. Many of its activities include complementary gender roles, with the gender division of labor determined largely by the physical force different activities demand. The more strength required for a task, the more likely it will be done by men, whereas activities that require particular skills, such as preparing lunch for workers, are done by women.

Family members do much of the farm work, but day laborers may be hired for labor-intensive tasks, such as clearing land. Women-headed households are more likely to hire day laborers for strenuous activities. Several farmers mentioned a shortage of day laborers as many of the young men who traditionally worked at farms have left their communities to work in mines, commercial farms, or cities.

The shortage of day laborers was mentioned by one farmer as a reason for increased reliance on the traditional huaypo (work exchange), in which community members work on each other’s farms in reciprocity, without cash payment. Both women and men participate in huaypo, but, when women reciprocate for work done by men, they are not expected to perform the activities that tradition assigns to men, which can make it more difficult for women to get men to reciprocate on their farms.

Ana explained the gender division of labor as follows: “Usually, in the mornings, the men go to the field and we women prepare lunch, and after we have lunch at noon, we all work in the field together, men and women.”

The traditional farming method, chiwi, consists of a series of consecutive activities, starting with preparation of the land—a task reserved for men—which involves removing vegetation. The work of planting is differentially shared as the man makes holes in the ground while the woman places a seed potato into each hole and covers it with soil using her foot.

While both men and women participate in most farm work, they often have gender-specific roles. An example is field maintenance after planting, in which the men traditionally break up hardened soil using a foot plow called chaki taclla while the women move the soil to create furrows. The harvest also has specific gender roles: the men dig up the potatoes while the women help gather them into piles and put them into sacks.

Transporting sacks of potatoes home is men’s responsibility, using llamas, mules, and, where possible, vehicles. Once delivered, women sort and classify the potatoes according to their size and condition, and determine which will be destined for sale, home consumption, or saved for planting in the next crop cycle. Potatoes selected for consumption or use as seed are stored in a dry, relatively dark room or shed, and placed on shelves covered with eucalyptus leaves and the Andean herb muña (Minthostachys sp.), to ward off potato tuber moths [73]. While gender roles and division of labor favor women’s control of seed potatoes—critical for in situ conservation and food security—their domain is largely limited to the household and community. Social norms that facilitate men’s mobility, however, provide them with opportunities to trade outside the community and access greater potato diversity.

4.2. Cultural Norms and Gender Roles

Cultural norms govern farming and other aspects of life in rural Andean communities, and some of them are expressed through prohibitions. While few of these affect men’s farming activities, some have the potential to act as barriers for women’s ability to achieve their productive potential or take advantage of the same opportunities as men. Farmers cited the following examples:

- Women are not supposed to use the chaki taclla, which could limit their ability to perform important farming activities and could lead women heads of households to hire day laborers, increasing their production costs.

- A woman cannot reciprocate all the jobs done by a man under the huaypo work exchange because she is only supposed to do activities that are appropriate for her gender. This limits women’s equitable access to labor provided through this traditional practice of reciprocity.

- There is a belief that a woman should not enter a field where potatoes are being grown if she is menstruating because she could cause the crop to develop late blight disease, which clearly restricts a woman’s ability to participate in agricultural activities.

- Prohibitions for men are fewer and less restrictive:

- It is said that men should not take potatoes out of a pot, otherwise a fox will dig up potatoes in his field. While a folk tale, this saying validates women’s domain over the kitchen, and it reflects a tradition that a man should be served rather than participating in the preparation of meals.

- Men should not handle the potatoes in storage because they are likely to damage them. While this may inconvenience men, it strengthens women’s control over potatoes stored for family consumption, eventual sales, or planting the next season, and thus has positive effects on both food security and in situ conservation. As Marta, a custodian from the community of Huachón, observed: “If men are allowed to take potatoes out of storage, they disappear more quickly.”

Compliance with most of these prohibitions has decreased, especially those that affect a woman’s ability to do farm work. This could be due to the shortage of farm workers in many communities, and the fact that more households are headed by women as men migrate to other areas in search of more lucrative employment. The shortage of farm workers has led some younger women to learn to use the chaki taclla, or older women to do jobs they might have hired men for in the past. This reflects an erosion of the gender division of labor and social norms that restrict women’s agricultural activities. Nevertheless, traditional norms and prohibitions continue to influence men’s perceptions of what kind of work a woman can or should do, and this can limit opportunities for women to earn money or exchange work with men through the huaypo tradition. Most of the farmers interviewed said they would rather hire a man than a woman to do many of the tasks on their farm. Amanda, a 51–year-old head of household in Paucartambo, explained that she prefers to use potatoes stored from her last harvest to pay men to help her with farm work because she has had trouble getting help through huaypo: “People say no, that I’m not a man, so I can’t reciprocate their labor,” she said.

4.3. Motivations for Potato Biodiversity Management

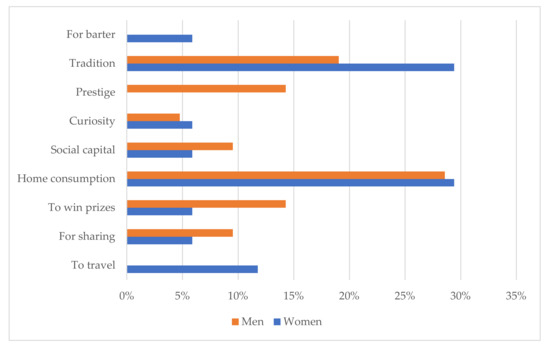

To effectively support endogenous potato diversity management, it is important to understand what motivates farmers. The main motivation for conserving and cultivating native potatoes cited by both men and women was that they like to eat them and want to ensure they have enough for their household needs during the year. While men and women expressed some different reasons for conserving native potato biodiversity, most motivations were mentioned by both, although to varied degrees (Figure 2). The motivations mentioned only by men or women reflect social norms that limit women’s access to resources or participation in biodiversity fairs and meetings, which means most receive little recognition of their role as potato custodians.

Figure 2.

Motivations for conserving native potatoes comparatively mentioned by women and men.

4.3.1. Motivations Mentioned by Both Women and Men

- For home consumption: The most common reason cited for growing native potatoes was to consume them. Farmers mentioned the varied flavors and colors of native potatoes and their nutritional value. Marta was one of several women who mentioned nutrition: “We grow them because they are delicious and also nutritious, so they are good for the children.”

- Curiosity: Inquisitiveness is an attribute that some native potato custodians mentioned since it motivates them to look for different varieties to increase the diversity in their fields and to understand the attributes of each variety. According to Ricardo, a 65-year-old custodian from Pasco district, “Other people aren’t as curious, and don’t plant them, but because we are curious and have grown these floury (native) potatoes since we were children, we make the effort to continue planting them, to continue growing them.”

- To win prizes: Custodians sometimes participate in agricultural fairs and other events organized by municipalities or government institutions that feature contests in which prizes are awarded to farmers with exceptional potato biodiversity. Men mentioned this motivation more than women.

- Tradition: Both men and women cited tradition as a motivation, noting that they have eaten native potatoes since they were children, but more women mentioned it than men.

- Social capital: Contact with professionals from the private or public sectors resulting from in situ conservation may help farmers sell their native potatoes or obtain support for participation in events or projects related to agrobiodiversity management. Men were more likely than women to mention this motivation.

- For sharing: This can refer to “gift potatoes”—a mix of the best-tasting varieties that farmers prepare for friends or family, such as relatives who visit them from the city—or a simple contribution to community members in need. As the potato custodian Julia explained: “I, of course, also give some (potatoes) to those old people who no longer farm. I share them here and there, so that we all consume the (native) potato.”

4.3.2. Motivations Mentioned Only by Women

- For barter: Barter is a fairly common practice in rural Peru, but only one woman interviewed mentioned that she exchanges native potatoes for other products.

- To travel: Most rural women in Peru have few opportunities to travel, and some mentioned that native potatoes have enabled them to visit other parts of the country to participate in meetings or events. Ana, AGUAPAN’s vice president, explained that she has travelled to several Peruvian cities she had never been to before for meetings and events, has traveled to Ecuador for a training in potato seed production, and to Geneva, Switzerland for a course on intellectual property rights. “Thanks to these little potatoes, I’ve gotten to visit places I never thought I would,” she said. “I feel blessed because I’ve been able to get to know places, people and new experiences I never imagined.”

4.3.3. Motivations Mentioned Only by Men

- Prestige: Only men mentioned prestige, which refers to the pride they feel for conserving native potatoes and the recognition they, their families, and their communities receive. As Rafael, a 62-year-old custodian from Pasco district, explained: “All my neighbors know who I am, and even if I hardly know them, I give them some of my potatoes. I feel proud to be able to grow them.” Interviews confirmed that men enjoy greater visibility and recognition as potato custodians even though women play a central role in the community management of the crop’s biodiversity. The lack of recognition is one of various barriers that hinder the empowerment that women could gain from biodiversity conservation.

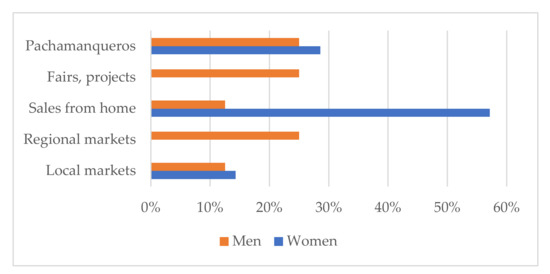

4.4. Sales of Native Potatoes

Though farmers primarily grow native potatoes for food security, most also sell a portion of their harvests, and there are gender differences in how and where they are sold (Figure 3). When a family has enough potatoes stored for their own needs, they may sell the surplus, or the woman may use it as barter to obtain other foods or household goods when needed. Native potatoes may be sold from home, at local or regional markets, at agrobiodiversity fairs, or to pachamanqueros (people involved in the preparation and sale of the traditional Andean dish pachamanca—a mixture of meats, potatoes, faba beans, and herbs baked with hot stones in an underground oven. AGUAPAN has created a brand (Miski Papa) and market innovations to add value to members’ potatoes, but it was new enough when this research was undertaken that no farmers mentioned it.

Figure 3.

Markets comparatively mentioned by women and men.

While pachamanqueros constitute an important market for both men and women, men sell a significant portion of their production in markets or agricultural fairs, which indicates greater mobility, whereas women are more likely to sell potatoes locally, from their homes or at local markets, which implies lower prices.

“When you produce a good quantity, you can sell some. They (pachamanqueros) look for you at harvest time and ask, ‘Have you got potatoes to sell?’,” explained Lorena, a custodian from Yanacancha. She added that pachamanqueros prefer “resistant” varieties that can be stored for months without significant loss of quality.

Miguel, a custodian from Paucartambo district, also mentioned pachamanqueros: “If I have more than enough (native potatoes), I sell some. Last year I managed to harvest 25 sacks, because there was no frost, so I sold to a pachamanquero in Carhaumayo who makes pachamanca every day,” he said. “Why can I sell to this pachamanquero? Because the native potatoes I have are different. They have different flavors.”

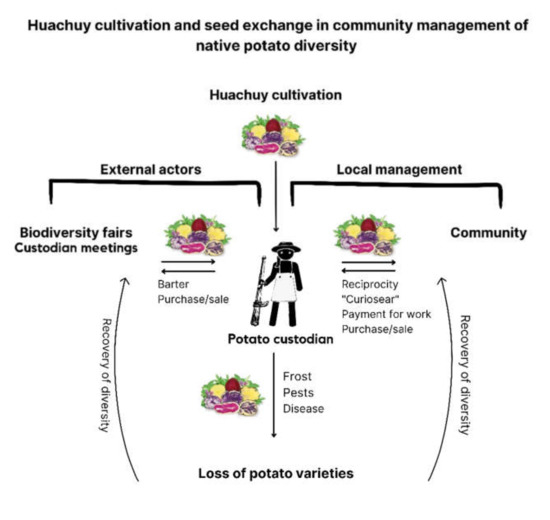

5. Discussion

In this study, we observed examples of traditional practices that contribute to community agrobiodiversity management. One of the most elemental is huachuy, or chaqru, Quechua terms that refer to the practice of growing a diversity of potato cultivars in the same plot and consuming them in a comparable mix [17,18,33]. This endogenous practice of Andean potato-growing communities has been strengthened by exogenous efforts to promote in situ conservation, which includes biodiversity fairs and custodian meetings that facilitate farmer exchange of seed potatoes [32].

5.1. Seed Management

The selection, allocation, and storage of native potatoes saved as seed for the next crop cycle is another fundamental component of biodiversity management [7]. The vital role of women in this area has been well documented and was confirmed by interviews and observation [4,5,7]. Women have ample knowledge of the culinary quality and agronomic characteristics of different varieties and often make the final decision regarding the selection and use of seed [4,7,15]. In addition to managing the seed potatoes, Andean women transmit their knowledge of native potato cultivars to their daughters and granddaughters, thereby planting seeds of future biodiversity conservation [4,7]. Interventions that aim to strengthen community biodiversity management need to recognize this valuable role and adopt approaches that can strengthen and facilitate recognition of it.

Though establishment of seed banks has been an important practice in community biodiversity management, none of the communities studied have them. Instead, seed potato selection and management are carried out at a household level, coupled with exchange of seed on a community level and beyond, which together constitutes an informal seed system that has been effective at conserving biodiversity and in which women traditionally occupy a central role [7,17,39]. Shrestha et al. noted that communities are open systems with regard to plant genetic resources, with inflows and outflows, and the informal seed systems in these communities have significant inflows and outflows of native potato diversity thanks to events that facilitate seed exchange and the active initiative of custodians to obtain new varieties through barter, purchase, or curiosear [74]. Curiosear, the practice of taking a few tubers of varieties one likes from the field of another farmer, is an accepted and established component of this informal seed system, facilitating the flow of native potato genetic resources (Figure 4) [37].

Figure 4.

Huachuy cultivation and inflow/outflow of native potato diversity.

This seed flow is important for maintaining varietal diversity on farms and in general. Custodians mentioned loss of native potato cultivars due to pests, disease, frost, or theft of large quantities (as opposed to curiosear, which entails small quantities). Julia, a 58-year-old custodian from Pasco district who grows more than 70 varieties with her husband, described discovering that some had been lost: “I told my husband, we’ve lost so many seed potatoes, various (varieties) are missing, we should have selected more seed, I told him. Now I’m missing some.”

However, Julia explained that she and her husband have been able to replace lost varieties, and even expand the diversity they manage. “My husband has bought potato varieties at the (biodiversity) fairs, one or two here, one or two there, that’s how we’ve increased our number of potatoes,” she said. She added that she has also sold seed potatoes to neighbors of varieties they had lost.

Ana, who lives and farms with her parents, explained that they have also lost varieties. “We have a goal that, if this year we’ve lost a variety, we have to find it one way or another, whether by buying it or trading for it.”

Seed management is strongly in the domain of women as a result of the gender division of labor, and they play a critical role in potato biodiversity management, yet the process is complex. Comments by women interviewed indicate that social norms and domestic circumstances largely restrict them to their household and community, limiting their access to greater genetic resources to replace lost varieties and enhance the potato diversity of their farms.

5.2. Andean Traditions

The communities studied share traditions and a cosmovision common in the Central Andes, such as the belief that the potato, and all things on Earth, are alive [5,6,35]. In a study of communities in the province of Moho, Puno, in southern Peru, for example, Apaza observed that farmers considered the potato to be a living being that needs to be raised by farmers, and that, by raising potatoes, men and women contribute to the conservation of the entire landscape [6].

This belief is reflected by an anecdote shared by Marta: “Sometimes the potato cries, because we don’t appreciate it, because we don’t take care of it. Sometimes it’s in the sun, because we leave it outside, and the birds start picking at it, and because of all this, it cries.”

Like the perception of a living landscape, the tradition of reciprocity is a defining component of Andean culture, influencing aspects of agriculture ranging from how the need for farm labor is resolved to providing access to tools or seed potatoes. Reciprocity is of an economic nature and is linked to a strategy of survival, since the parties involved act according to their own interests, but that calculated behavior is masked by the courtesy of giving and receiving gifts [75].

Both men and women make use of the form of reciprocity called huaypo, which involves working on each other’s farms without remuneration. However, women farmers are disadvantaged by the gender division of labor and perceptions that limit the agricultural activities they are supposed to perform, which can affect men’s willingness to exchange labor with them. Traditional gender roles and social norms may thus hinder women’s access to labor and their ability to benefit from reciprocity as fully as men.

Reciprocity is part of a broader Andean vision of roles, responsibilities, and connectivity in the natural world [6]. The farmer and the potato are interdependent as the farmer plants and cares for the potato and the potato nourishes the farmer and his or her family, part of a harmonious balance that extends beyond the farmer and crop to encompass the land, nature, and society [6].

As Marco, a 65-year-old custodian from the community of Huayo, explained: “The potato is for everyone, for the poor, for the travelers, for the ancestors. The potato is for everyone, for the birds, even for the worm.”

After describing how she watched birds eating her potatoes in the field instead of chasing them off, Ana echoed this sentiment: “Because, it is said, the animals taste your harvest, they have eaten well, they feel satisfied, they thank God, and God multiplies your harvest. That’s why they say that we plant for everyone.”

5.3. Subsistence and Income

While confirming the enduring power of many Andean traditions and beliefs, we observed how traditional livelihood strategies are merging with modern ones through parallel communal and individual control of resources [76,77]. Farmers’ life strategies once differed from the more individualistic, market-oriented focus of urban populations, but they increasingly need to engage in the national economy to acquire goods and services—such as mobile phones—that have become essential. This is one reason farmers grow improved potato varieties as well as native potatoes, because the modern varieties have considerably higher yields and strong markets. Native potatoes, on the other hand, are part of their traditional survival strategy, the product of a farming system that prioritizes food security.

Farmers primarily grow native potatoes on communal land and may share or trade tools, labor, and seed, maintaining a tradition of reciprocity that is rare in urban areas. Out-migration and greater integration with urban economies are changing rural communities, contributing to the erosion of traditional social norms and life strategies, as well as changes in gender roles, relations, and division of labor [19,42,78]. The migration of men has forced many women to take greater responsibility for agricultural production, increasing their workload, but this has also weakened social norms that traditionally restricted women’s options, which could enhance their agency in decision-making and facilitate empowerment.

Generating income has traditionally been the domain of men, while household expenses are controlled by women, although there is clearly flow between the two [77]. Men enjoy access to more market options, while women face barriers that limit their mobility, access to potato diversity, and market opportunities. On a local level, however, native potatoes help women ensure food security—an invaluable benefit in times of crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic—and enable them to obtain cash, barter for other products, or pay farm workers. All of this contributes to food and economic security and empowerment, which would be expected to motivate women to continue conserving their potato diversity. However, there is a need for interventions that enhance women’s agency in decision-making, mobility, and ability to participate in trade beyond the local level. This can help women farmers boost their potato diversity through external linkages and increase the positive benefits they achieve through native potato cultivation.

5.4. Interventions and Opportunities

External actors have played a role in supporting in situ conservation in the communities studied and have facilitated potato custodians’ travel to agrobiodiversity fairs and meetings. Those opportunities help farmers increase the number of varieties they conserve and participate in contests and events that enhance their sense of pride. However, while women custodians mentioned such events as motivations for in situ conservation, male custodians were more likely to mention prestige and opportunities to win prizes, indicating they had actively engaged in those events.

Women have traditionally enjoyed less visibility and mobility than men, especially women with young children. This can limit their access to resources, better markets for their crop, and other opportunities.

Men have come to occupy the role of potato custodian through participation in public spaces, whereas gender norms and relations may limit women’s agency and prevent them from receiving full recognition of their deep knowledge of native potato biodiversity and the key role they play in its conservation [5,7,19].

While interviews confirmed that efforts to strengthen in situ conservation have contributed to empowerment, ensuring that empowerment is inclusive remains a challenge. While one third of AGUAPAN’s members are women, some mentioned difficulty fully participating in the association’s meetings and events due to their numerous responsibilities as wives, mothers, daughters, and farmers. Julia, for example, said that only her husband attends meetings and other events: “I’m mostly at home or with my animals. My son is young and needs me to cook for him, so I don’t leave. My husband travels, not me.”

It is notable that women who reported more participation in those activities were either single mothers or older women whose children are adults. This is a reminder that rural women are hardly a homogenous group, and that it is important to take factors such as marital status and motherhood into account in efforts to foster empowerment. While traditional gender norms and relations, and poverty, create barriers for women, there is clearly potential to enhance their agency in decision-making linked to crop diversity management. Interventions need to improve women’s access to resources and ability to participate in fora, events, and markets so that the conservation of biodiversity becomes a way for them to empower themselves and advance toward gender equality.

An example of this potential is the case of Ana, a single mother who has twice been elected vice president of AGUAPAN and is working to make it more inclusive, and to encourage members to share their knowledge of native potatoes with their children. She noted that women are becoming more active in AGUAPAN and that the association is doing a better job of communicating the importance of their role. “In AGUAPAN, we want to visibilize women’s role in biodiversity conservation,” she said. “It’s important to know that men aren’t the only ones who can be leaders in a group, that we women are capable of many things.”

While AGUAPAN has facilitated members’ participation in agrobiodiversity fairs and other events that provide opportunities for them to sell their native potatoes, the organization recently created a brand for those potatoes, Micki Papa, and launched a system of direct sales to customers in Lima, which is home to nearly a third of Peru’s population [79]. Ana noted that one goal of the brand is to develop an urban market for huachuy, the mix of varieties, the way that farmers consume them so that sales contribute to diversity conservation.

There are indications that agrobiodiversity fairs and contests that award prizes for outstanding collections of native potato varieties have incentivized crop diversity conservation, but they involve a limited number of beneficiaries. AGUAPAN distributes a portion of the funds it receives from donors directly to its members to cover the cost of school supplies, medical emergencies, or other needs (comment by Ana). This is a type of payment for agrobiodiversity conservation services—modeled after payments for environmental services—which has been used in various countries in the past decade, has been found to be cost-effective, and has the potential to be a gender-equitable crop diversity conservation approach [19,80].

Whatever approach is taken to promote the conservation of native potato and other crop diversity, it is important to understand the cultural implications, recognize the risks of negative impacts, and consider power asymmetries to ensure that an intervention empowers women and contributes to gender equality. Gender and cultural issues are inseparable, so acknowledging cultural norms and gender roles and relations is essential for effective agricultural research and development interventions [9].

6. Conclusions

6.1. Limitations

The most significant limitation was the COVID-19 pandemic, which made it impossible to travel to the communities for further research. After clarifying some cultural concepts via telephone, or with the help of local allies, the decision was made to write this paper based on the research that had been completed. Another limitation that became apparent early in the study was the low participation of women in the focus group, which resulted in the decision to collect information through in-depth and semi-structured interviews instead. Furthermore, most custodians were male heads of household and women were a very reduced group. To address this challenge, the number of women members of AGUAPAN was used as a criterion for the selection of the regions to be included in the study.

6.2. Conclusions

The gender roles and relationships, livelihood strategies, and traditions documented here are linked to an ancestral system that has guided Andean farmers, men and women, for centuries and has helped them make rational decisions about adopting technologies or activities to meet their economic and social needs [5,15]. Over the five centuries since the Spanish conquest, this system has proven to be both socially and biologically sustainable. However, as roads, technologies, and the influence of globalization reach once remote communities, they pave the way for young people to move to urban areas, where obesity and malnutrition are on the rise. Evidence of the social cost of unhealthy modern diets and the nutritional value of native potatoes and other ancestral Andean crops should provide outside validation of the importance of sustaining these farming systems and incentives for women custodians to share their knowledge of native potato cultivation and conservation with their daughters.

An analysis of the different elements of the Social Relations Framework in the context of potato biodiversity conservation in the high Andes showed that the links between gender norms, roles, division of labor, and decision-making are mutually reinforcing. Changes in this case have been triggered by external factors influencing access to and control over resources, and recognition of the role of custodian farmers within the community and beyond. Cultural traditions and gender norms give men an advantage for capitalizing on the benefits of native potatoes, but women also reap varied benefits from their cultivation that could be enhanced through gender responsive approaches.

This study has started a process of exploring how gender roles and norms influence the conservation and utilization of potato biodiversity in Andean farming communities. However, further research is needed to adapt the existing frameworks and methods to properly reflect social differentiation and the underlying causes of gender inequality in different institutional and organizational arrangements that govern biodiversity conservation, for example, how the existence and mechanics of informal kinship networks and women’s groups for knowledge and seed exchange influence conservation decisions and practice. Future research should explore the varied differences in decision-making at the household, community, and organizational level and how these differences affect and are affected by biodiversity conservation practices and experiences.

Our study confirms the need for inclusive approaches to promoting community management of native potato agrobiodiversity that empower both women and men and facilitate the sustainable use of that resource for food and nutrition security and development. This requires acknowledging traditions and gender roles, recognizing their importance, and designing approaches that take them into account.

Understanding the motivations of men and women regarding the preservation and use of native potato biodiversity can contribute to the design of projects or policies that strengthen in situ conservation and improve rural incomes and food security without exacerbating the gender gap. Interventions and approaches that are more culturally appropriate and gender equitable, and take into account the tradition of reciprocity, the symbolic universe, and other aspects of the Andean cosmovision that the native potato forms a part of can be more effective in improving the management of the region’s invaluable potato diversity. In the words of Jacqueline D. Lau: “The time is ripe for biodiversity conservation research and practice to move toward the pole star of gender equity” [59] (p. 1591).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.P. and B.H.; Data curation, C.A.M.; Formal analysis, C.A.M.; Funding acquisition, B.H.; Investigation, C.A.M. and R.C.C.; Methodology, V.P. and B.H.; Project administration, B.H.; Resources, V.P. and R.C.C.; Software, C.A.M.; Supervision, B.H.; Validation, V.P., M.S., and B.H.; Visualization, C.A.M.; Writing—original draft, C.A.M. and D.D.; Writing—review & editing, C.A.M., D.D., V.P., M.S., and B.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was undertaken as part of and funded by the CGIAR Research Programs on Roots, Tubers and Bananas (RTB) and the CGIAR Gender Platform and supported by CGIAR Trust Fund contributors (https://www.cgiar.org/funders/; accessed on 2 March 2022).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study was non-invasive and did not involve biological human experiments and patient data.

Informed Consent Statement

At the beginning of this study, all participants gave prior and informed consent as part of a process that included an explanation of the research process and objectives and a commitment to ensure that the information provided would be managed according to the wishes of the farmers.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available to protect the privacy of the study’s participants.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for providing constructive comments and suggestions that helped improve the article, and Henry Juarez, of CIP, for creating the map of the study area (Figure 1). Special thanks to the communities in the study for their hospitality and support of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jones, A.D.; Creed-Kanashiro, H.; Zimmerer, K.S.; de Haan, S.; Carrasco, M.; Meza, K.; Cruz-Garcia, G.S.; Tello, M.; Plasencia Amaya, F.; Marin, R.M.; et al. Farm-Level Agricultural Biodiversity in the Peruvian Andes Is Associated with Greater Odds of Women Achieving a Minimally Diverse and Micronutrient Adequate Diet. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuijten, E. Gender and Management of Crop Diversity in The Gambia. J. Political Ecol. 2010, 17, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Boef, W.S.; Thijssen, M.H.; Shrestha, P.; Subedi, A.; Feyissa, R.; Gezu, G.; Canci, A.; Fonseca Ferreira, M.A.J.D.; Dias, T.; Swain, S.; et al. Moving Beyond the Dilemma: Practices That Contribute to the On-Farm Management of Agrobiodiversity. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 788–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudege, N.N.; Sarapura, S.; Polar, V. Gender Topics on Potato Research and Development. In The Potato Crop: Its Agricultural, Nutritional and Social Contribution to Humankind; Campos, H., Ortiz, O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 475–506. [Google Scholar]

- Sarapura, S.; Hambly Odame, H.; Thiele, G. Gender and Innovation in Peru’s Native Potato Market Chains. In Transforming Gender and Food Security in the Global South; Njuki, J., Parkings, J.R., Kaler, A., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, UK; New York, NY, USA; International Development Research Centre (IDRC): Ottawa, Canada, 2016; pp. 160–185. [Google Scholar]

- Apaza, J. Cosmovisión Andina de La Crianza de La Papa. In Manos Sabias para Criar la Vida. Tecnología Andina; Larraín, H., van Kessel, J., Eds.; Ediciones Abya-Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 2000; pp. 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Tapia, M.E.; de la Torre, A. Women Farmers and Andean Seeds; IPGRI: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Women in Agriculture: Closing the Gender Gap for Development. In The State of Food and Agriculture; FAO, Ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Meinzen-Dick, R.; Quisumbing, A.; Behrman, J.; Biermayr-Jenzano, P.; Wilde, V.; Noordeloos, M.; Ragasa, C.; Beintema, N. Engendering Agricultural Research; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2010; p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan, S.; Rodriguez, F. Potato Origin and Production. In Advances in Potato Chemistry and Technology; Singh, J., Kaur, L., Eds.; Academic Press, Elsevier: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Devaux, A.; Kromann, P.; Ortiz, O. Potatoes for Sustainable Global Food Security. Potato Res. 2014, 57, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshe, R.; Argumedo, A. Ayni, Ayllu, Yanantin and Chanincha: The Cultural Values Enabling Adaptation to Climate Change in Communities of the Potato Park, in the Peruvian Andes. GAIA—Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2016, 25, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, H. Impact of the Potato on Society. Am. J. Potato Res. 2016, 93, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). International Year of the Potato 2008—New Light on a Hidden Treasure; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brush, S.B. Farmers’ Bounty: Locating Crop Diversity in the Contemporary World; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brush, S.B.; Carney, H.J.; Humán, Z. Dynamics of Andean Potato Agriculture. Econ. Bot. 1981, 35, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, A.; de Haan, S.; Juarez, H.; Burra, D.D.; Plasencia, F.; Ccanto, R.; Polreich, S.; Scurrah, M. The Spatial-Temporal Dynamics of Potato Agrobiodiversity in the Highlands of Central Peru: A Case Study of Smallholder Management across Farming Landscapes. Land 2019, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Juarez, H.; Plasencia, F.; de Haan, S. Zooming in on the Secret Life of Genetic Resources in Potatoes: High Technology Meets Old-Fashioned Footwork. In Esri Conservation Map Book; Esri: Redlands, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gruberg, H.; Meldrum, G.; Padulosi, S.; Rojas, W.; Pinto, M.; Crane, T.A. Towards a Better Understanding of Custodian Farmers and Their Roles: Insights from a Case Study in Cachilaya, Bolivia; Bioversity International: La Paz, Bolivia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, C.K.; Brush, S.; Costich, D.E.; Curry, H.A.; de Haan, S.; Engels, J.M.M.; Guarino, L.; Hoban, S.; Mercer, K.L.; Miller, A.J.; et al. Crop Genetic Erosion: Understanding and Responding to Loss of Crop Diversity. New Phytol. 2021, 233, 84–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerer, K.S.; de Haan, S. Informal Food Chains and Agrobiodiversity Need Strengthening—Not Weakening—to Address Food Security amidst the COVID-19 Crisis in South America. Food Sec. 2020, 12, 891–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoros, W.; Salas, E.; Hualla, V.; Burgos, G.; de Boeck, B.; Eyzaguirre, R.; zum Felde, T.; Bonierbale, M. Heritability and Genetic Gains for Iron and Zinc Concentration in Diploid Potato. Crop. Sci. 2020, 60, 1884–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, S.; Núñez, J.; Bonierbale, M.; Ghislain, M. Multilevel Agrobiodiversity and Conservation of Andean Potatoes in Central Peru. Mt. Res. Dev. 2010, 30, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.; Salas, A.; Chavez, O.; Gomez, R.; Anglin, N. Ex Situ Conservation of Potato [Solanum Section Petota (Solanaceae)] Genetic Resources in Genebanks. In The Potato Crop: Its Agricultural, Nutritional and Social Contribution to Humankind; Campos, H., Ortiz, O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 109–138. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan, S.; Burgos, G.; Liria, R.; Rodriguez, F.; Creed-Kanashiro, H.M.; Bonierbale, M. The Nutritional Contribution of Potato Varietal Diversity in Andean Food Systems: A Case Study. Am. J. Potato Res. 2019, 96, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Riego. Análisis de Mercado—Papa 2020. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/sse/informes-publicaciones/1368947-analisis-de-mercado-papa-2020 (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Riego. Cultivos de Importancia Nacional—Papa. Available online: https://www.midagri.gob.pe/portal/23-sector-agrario/cultivos-de-importancia-nacional/183-papa (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Pradel, W.; Hareau, G.; Quintanilla, L.; Suarez, V. Adopcion e Impacto de Variedades Mejoradas de Papa en el Perú: Resultado de una Encuesta a Nivel Nacional (2013); International Potato Center: Lima, Perú, 2017; p. 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Devaux, A.; Ordinola, M.; Andrade-Piedra, J.L.; Thiele, G. Marketing Native Crops to Improve Rural Andean Livelihoods. In Vibrant Mountain Communities. Regional Development in Mountains: Realizing Potentials, Tackling Disparities; Wymann von Dach, S., Ruiz Peyré, F., Eds.; Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), University of Bern, with Bern Open Publishing (BOP): Bern, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, D.; Samanamud, K. La Revolucion de La Papa Nativa En Perú; Resumen de Innovacion 2 de Papa Andina; International Potato Center: Lima, Peru, 2017; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan, S. Custodians of Potato Biodiversity. Virginia Tech College of Agriculture and Life Science Global. Available online: https://globalagriculturalproductivity.org/custodians-of-potato-biodiversity/ (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Grupo YANAPAI. Association of Guardians of the Native Potato from Central Peru: AGUAPAN—Grupo Yanapai. Available online: https://yanapai.org/projects/?lang=en (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Sociedad Peruana de Derecho Ambiental (SPDA). The Association of Potato Biodiversity Guardians from Central Perú: A New Model of Self-organization for Benefit Sharing. Available online: https://spda.org.pe/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/DIPTICO-AGUAPAN-INGLES.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Valladares, L.; Olivé, L. ¿Qué son los Conocimientos Tradicionales? Apuntes Epistemológicos para la Interculturalidad. Cult. Represent. Soc. 2015, 10, 61–101. [Google Scholar]

- Garrafa, R.S. Simbolismo y ritualidad en torno a la papa en los Andes. Investig. Soc. 2011, 15, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerer, K.S.; Carney, J.A.; Vanek, S.J. Sustainable Smallholder Intensification in Global Change? Pivotal Spatial Interactions, Gendered Livelihoods, and Agrobiodiversity. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sust. 2015, 14, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boef, W.S.; Verhoosel, K.S.; Thijssen, M. Community Biodiversity Management and Empowerment. In Community Biodiversity Management: Promoting Resilience and the Conservation of Plant Genetic Resources; de Boef, W.S., Subedi, A., Peroni, N., Thijssen, M., O’Keeffe, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 365–377. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, I.; Lovera, S. New Times for Women and Gender Issues in Biodiversity Conservation and Climate Justice. Development 2017, 59, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puskur, R.; Mudege, N.N.; Njuguna-Mungai, E.; Nchanji, E.; Vernooy, R.; Galiè, A.; Najjar, D. Moving Beyond Reaching Women in Seed Systems Development. In Advancing Gender Equality through Agricultural and Environmental Research: Past, Present, and Future; Pyburn, R., van Eerdewijk, A., Eds.; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 113–145. [Google Scholar]

- Lüttringhaus, S.; Pradel, W.; Suarez, V.; Manrique-Carpintero, N.C.; Anglin, N.L.; Ellis, D.; Hareau, G.; Jamora, N.; Smale, M.; Gómez, R. Dynamic Guardianship of Potato Landraces by Andean Communities and the Genebank of the International Potato Center. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2021, 2, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafur, M.; Gumucio, T.; Turin, C.; Twyman, J.; Martínez Barón, D. Género y Agricultura en el Perú: Inclusión de Intereses y Necesidades de Hombres y Mujeres en la Formulación de Políticas Públicas; CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/66136 (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Patel-Campillo, A.; Salas García, V.B. Un/Associated: Accounting for Gender Difference and Farmer Heterogeneity among Peruvian Sierra Potato Small Farmers. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 64, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsop, R.; Heinsohn, N. Measuring Empowerment in Practice: Structuring Analysis and Framing Indicators; Policy Research Working Paper; No. 3510; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, N. Reversed Realities: Gender Hierarchies in Development Thought; Verso: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Deda, P.; Rubian, R. Women and Biodiversity: The Long Journey from Users to Policy-Makers. Nat. Resour. Forum 2004, 28, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momsen, J.H. Gender and Biodiversity: A New Approach to Linking Environment and Development. Geogr. Compass 2007, 1, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. The Power to Choose: Bangladeshi Women and Labor Market Decisions in London and Dhaka; Verso: London, UK, 2002; p. 464. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, N. Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment: A Critical Analysis of the Third Millennium Development Goal 1. Gend. Dev. 2005, 13, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polar, V.; Ashby, J.A.; Thiele, G.; Tufan, H. When Is Choice Empowering? Examining Gender Differences in Varietal Adoption through Case Studies from Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D.; Mbatha, P.; Muhl, E.-K.; Rice, W.; Sowman, M. Governance Principles for Community-Centered Conservation in the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2020, 2, e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia, C.; Gilles, J. Gender and Resource Management: Households and Groups, Strategies and Transitions. Agric. Hum. Values 2001, 18, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtel, J.D. Gender, Poverty and the Conservation of Biodiversity. A Review of Issues and Opportunities; MacArthur Foundation Conservation White Paper Series; MacArthur Foundation: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelali-Martini, M.; Amri, A.; Ajlouni, M.; Assi, R.; Sbieh, Y.; Khnifes, A. Gender Dimension in the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Agro-Biodiversity in West Asia. J. Socio-Econ. 2008, 37, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C. The Politics of Recognition. In Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition; Gutmann, A., Ed.; Princeton University Press: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 25–73. [Google Scholar]

- McNay, L. Against Recognition; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Women. Towards a Gender-Responsive Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework: Imperatives and Key Components. A Submission by the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN-Women) as an Input to the Development of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework 2019. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/api/v2013/documents/22969EF8-52C8-9BE5-26A7-9D306C2FBEAA/attachments/208266/UNWomen.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Song, Y.; Vernooy, R. Seeds of Empowerment. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2010, 14, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo, E.C.; Hinrichs, J.S. Curadoras de Semillas: Entre Empoderamiento y Esencialismo Estratégico. Rev. Estud. Fem. 2015, 23, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.D. Three Lessons for Gender Equity in Biodiversity Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 1589–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F. Reframing Public Policy: Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thanh, N.C.; Thanh, T.T. The Interconnection Between Interpretivist Paradigm and Qualitative Methods in Education. Am. J. Educ. Sci. 2015, 1, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Barillaro, P.; Metz, J.L.; Perran, R.; Stokes, W. Constructivist Epistemology: An Analysis. Available online: https://studylib.net/doc/7527138/constructivist-epistemology--an-analysis (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Callupe, F.; Turco, J. Caracterizacion del Departamento de Pasco; Banco Central de Reserva del Perú: Huancayo, Perú, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Coordenadas Geográficas de Cerro de Pasco—Latitud y Longitud. Available online: https://www.geodatos.net/coordenadas/peru/cerro-de-pasco (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Ridgeway, C.L. Framed Before We Know It: How Gender Shapes Social Relations. Gend. Soc. 2009, 23, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boef, W.S.; Thijssen, M. Herramientas de Trabajo Participativo con Cultivos, Variedades y Semillas. Una Guía Para Técnicos que Aplican Metodologías Participativas en el Manejo de la Agrobiodiversidad, Fitomejoramiento y Desarrollo del Sector Semillero; Wageningen University & Research: Wagening, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Geilfus, F. 80 Herramientas para el Desarrollo Participativo: Diagnóstico, Planificación, Monitoreo y Evaluación; Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA): San Jose, Costa Rica, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Sampieri, R.; Fernández Collado, C.; Baptista Lucio, P.; Méndez Valencia, S.; Mendoza Torres, C.P. Metodología de la Investigación; McGraw-Hill: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Miguélez, M. La Investigación Cualitativa Etnografica en Educación. Manual Teorico-Practico, 3rd ed.; TRILLAS: Mexico City, Mexico, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, B. La Entrevista en Profundidad: Una Técnica Útil Dentro del Campo Antropofísico. Cuicuilco 2011, 18, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International, Nvivo, version reread 1.3 (535); Software for qualitative analysis data; QSR International: Burlington, MA, USA, 2020.

- Otoya, V.L. Considerations for the Use and Study of the Peruvian “Muña” Minthostachys mollis (Benth.) Griseb and Minthostachys setosa (Briq.) Epling. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2020, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, P.; Shrestha, P.; Subedi, A.; Peroni, N.; de Boef, W.S. Community Biodiversity Management: Defined and Contextualized. In Community Biodiversity Management: Promoting Resilience and the Conservation of Plant Genetic Resources; de Boef, W.S., Subedi, A., Peroni, N., Thijssen, M., O’Keeffe, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, G.; Mayer, E. Reciprocidad e Intercambio en los Andes Peruanos. In Reciprocidad e Intercambio en los Andes Peruanos; Alberti, G., Mayer, E., Eds.; Instituto de Estudios Peruanos (IEP): Lima, Perú, 1974; pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Diez Hurtado, A. Cambios en la Ruralidad y en las Estrategias de Vida en el Mundo Rural. Una Relectura de Antiguas y Nuevas Definiciones. In Perú: El Problema Agrario en Debate; Diez Hurtado, A., Ráez Luna, E., Fort, R., Eds.; Seminario Permanente de Investigación Agraria (SEPIA): Lima, Perú, 2014; pp. 19–85. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, C.; Mayer, E. Kausana Munay: Queriendo La Vida: Sistemas Económicos en las Comunidades Campesinas del Perú, 1st ed.; Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú: Lima, Peru, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia-Díaz, M.; Polreich, S.; La Torre, M.D.L.Á.; de Haan, S. Local Knowledge of Native Potato (Solanum Spp.) for Long-Term Monitoring on Three Andean Communities of Apurimac, Peru. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 29, 64–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asociación de Guardianes de la Papa Nativa del Centro del Perú (AGUAPAN) Catálogo Miski Papa. Regalo de Los Andes. Colecciones de Los Guardianes de Papa Nativa; International Potato Center: Lima, Peru, 2020; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/111806 (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Drucker, A.G.; Ramirez, M. Payments for Agrobiodiversity Conservation Services: An Overview of Latin American Experiences, Lessons Learned and Upscaling Challenges. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |