Canada’s Impact Assessment Act, 2019: Indigenous Peoples, Cultural Sustainability, and Environmental Justice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Treaties and Environmental Assessments

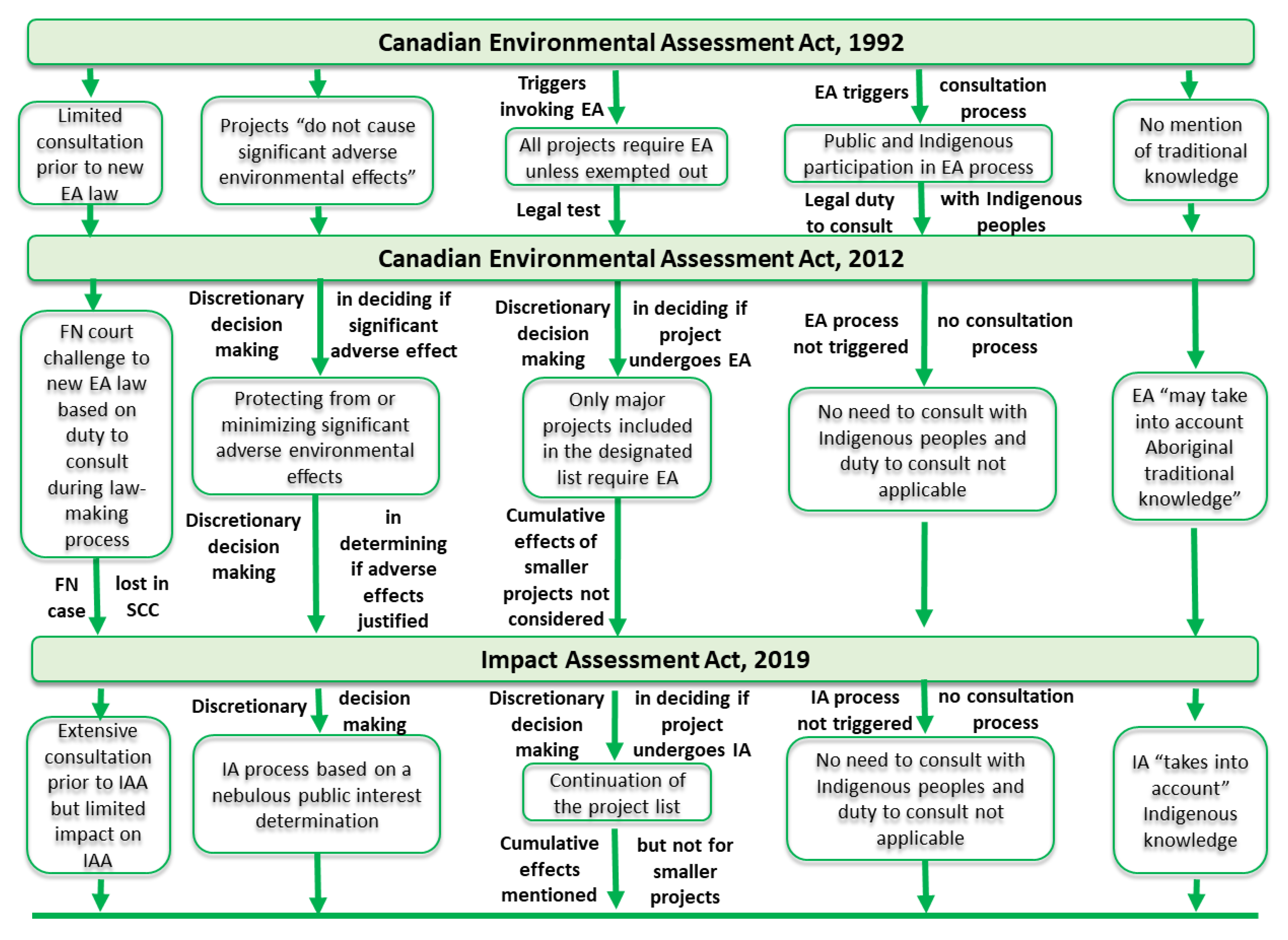

2.2. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012

2.3. An Indigenous Court Challenge to the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012

As a matter of practice and in furtherance of good public administration, consultation on policy options in the preparation of legislation is very often undertaken. But, it is not constitutionally required…If Parliament or a provincial legislature wishes to bind itself to a manner and form requirement incorporating the duty to consult Indigenous peoples before the passing of legislation, it is free to do so…But the courts will not infringe.

2.4. The Need for a New Environmental Assessment Process

2.5. Bill C-69, an Act to Enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to Amend the Navigation Protection Act and to Make Consequential Amendments to Other Acts

3. Methods

3.1. Geographical and Cultural Scope

3.2. Data Collection and Analyses

4. Results

4.1. A Pan-Indigenous Perspective on the Environment in Canada

First Nations are rights holders, who hold inherent and constitutionally-protected rights set out in their own governance and legal systems, as well as under Section 35 of the Constitution. In practice, this means that First Nations rights cannot be undermined by colonial interpretation of their rights (i.e., s.35). Instead, First Nations must first interpret and describe their inherent rights, grounded in Indigenous law, Indigenous legal traditions, and customary law. These legal orders, which lay the foundation for First Nations’ concepts of self-determination and sovereignty, are essential to starting true “Nation-to-Nation” dialogues and expressing the respect for our rights and title. For the millennia, prior to contact with European explorers, First Nations exercised control over their territories through their own governance authorities.

Our people occupied, governed, and acted as stewards of our territory prior to contact, at contact (AD 1792), at the British Crown’s assertion of sovereignty (AD 1846), and continue to do so today… Tsleil-Waututh holds a sacred, legal obligation and responsibility to our ancestors, current, and future generations to protect, defend, and steward the water, land, air, and resources of our territory. Our stewardship obligation includes the need to maintain and restore conditions that provide the environmental, cultural, spiritual, and economic foundation for our nation and community to thrive. The Tsleil-Waututh Nation does this through actively asserting and exercising its stewardship and governance rights.

4.2. A Canadian Pan-Indigenous Perspective on Development in Their Homelands

The status quo of pretending that major projects are being proposed in a pristine environment that result in zero impacts and play no role in shaping upstream and downstream impacts is fanciful and self-deluding.[116] (p. 2)

“Air We Cannot Breathe”…we have signs up all over the place about sour gas, and oil and gas activities…“Fish We Cannot Eat”…All of the fish in the reservoir system have high concentrations of methylmercury…“Land we Cannot Use to Hunt or Trap”…There are signs throughout the whole area that restrict our activity…“Animals We Cannot Eat”…a female caribou…a species-at-risk animal…was eating contaminated soil in a lease site that hadn’t been cleaned up. She died…“Water We Cannot Drink”. Areas…not affected by the Williston Reservoir and the methylmercury have coal mines on them, with high levels of selenium being dumped into them. There are signs…[warning] not to drink the water or eat the fish…“Forests we Cannot Use To Camp”…signs are up that restrict us from camping…sloughing has been happening since they flooded and went to full pool on the Williston Reservoir…It has been 40 years and it’s still sloughing there.

Here’s my observation. At this time in Canada…often Aboriginal people are cast in the role of folks adamantly opposed all the time to development. As we know…Canada is a resource rich nation and…a leading nation at a high level of development…and yet at the same time has certain values that it wants to protect and uphold around the environment …If there isn’t any investment in Canada in major projects…[the result] plays out in our community in high levels of unemployment, poor housing…a lack of infrastructure improvement and maintenance in our communities…we want to make sure that they [Indigenous children] enjoy the same living standards…along with other Canadians.

4.3. Enactment an Act Respecting a Federal Process for Impact Assessments and the Prevention of Significant Adverse Environmental Effects (Short Title: Impact Assessment Act, 2019)

4.3.1. Cultural Sustainability

‘Sustainability’ is a modern term, but sustainability was long in practice by our people and our ancestors. There were consequences that occurred when we strayed from our natural teachings, instructions, laws…It was (and is) a matter of survival. We had, and continue to have, deep connections to the land…the arrival of Europeans to our territory…has dramatically impacted our way of life.[105] (p. 3)

4.3.2. Discretionary Decision-Making Power and the Public Interest Determination

does not believe that the Minister’s obligation to consider project impacts on Indigenous “groups” as part of a public interest determination (Section 63) is sufficient…this approach does not respect Indigenous consent or decision making as to what is an “acceptable” impact to Indigenous rights and lands. The Act only acknowledges Canada as the exclusive decision making authority to make such a determination as part of the public interest test…impacts to the rights of Indigenous Nations should not be weighed against other interests (economic interests of Canada or local communities, etc.) in a manner that does not respect the very nature of the Indigenous rights which are at stake…the Act should…separate impacts to established Indigenous rights from the public interest test of Section 63.

there is a general lack of transparency and accountability on how decisions are made…in Sections 60–64…there is no requirement for the Minister to state how these rights have been considered in relation to the other considerations listed in s.63 or the “public interest”…the Minister, or Governor in Council, can trade off s. 35 Indigenous rights, but he/she has no requirement to state how or why these rights have been traded off to the “public interest”. Leaving discretionary power in the hands of the Minister or Governor in Council is certainly not transparent nor accountable, is prejudiced against the Indigenous peoples of Canada…not in the spirit of reconciliation.

4.3.3. The Designated Project List

4.3.4. Cumulative Impacts and Regional/Strategic Assessments

Over the past several decades our Traditional Territory has been subjected to waves of successive development that have heavily impacted our lands, waters, fish and animals that we have a relationship and rely upon. The cumulative impact of agriculture, hydro projects, oil and gas, oil sands, mining, forestry and over hunting and fishing have impacted the ecology of our lands and has made it difficult to impossible for our people to meet their livelihood and cultural needs and exercise their rights.

The Expert Panel suggests the Lower Athabasca Regional Plan (LARP) is a regional assessment. Fort McKay disagrees. LARP does not acknowledge the impact of industrial development on Aboriginal and Treaty Rights. It is incomplete and was not developed with reference to any baseline assessments. At best, it is a regional land use plan…LARP was developed without meaningful consultation. LARP was intended to manage industrial development effects but projects continue to be approved without systems to acknowledge, understand, or manage cumulative effects arising from these approvals.[111] (p. 10)

4.3.5. Substitution (One Project, One Review)

The [Federal] Minister continues to have broad discretionary powers under the Bill [C-69]—the power of substitution…does not lead to predictability and credibility especially when those decisions impact First Nations rights.[116] (p. 11)

It would be of significant concern…if the federal process was substituted for the provincial process…[should] require that substituted assessments meet the same standard as federal assessment.[107] (p. 4)

It is with regret that we must state, that the Government of Alberta has not acted honorably in its dealings with the DFN and has allowed our territory, our livelihood rights and our ability to feed our families to be heavily impacted.[104] (p. 5)

Any federal legislation providing for environmental or social assessment of development projects in the JBNQA [First Nations’ Cree] territory of Eeyou Istchee must ensure that the assessment is conducted by the federal environmental and social impact review panel, known as the COFEX, established under Section 22 of the JBNQA.[117] (p. 3)

[L]aid a framework for environmental, social, and impact assessments to be conducted by bodies whose members give Inuit a direct role in the assessments…in a culturally appropriate way… [through] Section 23 of the agreement…the main difference [compared to the Crees] being that the body responsible for assessmentsis called the COFEX-North and applies to the Inuit territory[135] (p. 5)

One of the main objectives of the regime is to ensure that the Crees are active participants in the orderly development of the resources in Eeyou Istchee so as to safeguard their hunting, fishing, and trapping rights, as detailed in Section 24 of the treaty.

the impact assessment regimes that are included within our land claims agreements are the outcome of extensive and careful negotiations. They are sensitive to the particular circumstances of the region and have been constructed with the rights of Nunavik Inuit in mind. Perhaps more importantly, they are relevant to and trusted by Nunavik Inuit.

4.3.6. Reconciliation

This is not a time to tweak legislation that doesn’t work, but an opportunity to create something that truly works toward reconciliation…move toward an economy that meets the needs of the current generation without compromising future generations’ ability to meet their own needs. The legislation must integrate free, prior, and informed consent in order to work toward reconciliation with Canada’s Indigenous peoples. The legislation must allow treaties and land claim agreements to be respected and fully implemented. Indigenous peoples have a tradition of sustainable, respectful development and use of the land and resources in their traditional territories…must be a shift from mitigating the worst negative impacts toward using impact assessment as a planning tool for true sustainability.[127] (p. 4)

if the final decision to approve a project can be made unilaterally by one party without confirmation from an affected First Nation that its views and concerns have been addressed. First Nations’ inherent jurisdiction must be recognized—including the ability to make final decisions at all stages of impact assessment in accordance with their own laws and customs… when the Government of Canada begins respecting and fulfilling commitments made in treaties, both historic and modern. This is important work in the journey of reconciliation and is essential to enable us to move forward together in a good way.[130] (p. 16)

there is a strong link between reconciliation and environmental assessment and the protection of our rights on our territories, a link that is becoming clearer to us every day…The problem is that government is defining what reconciliation relations are…First Nations’ rights and title cannot be undermined by the colonial interpretation of reconciliation.

4.4. An Act Respecting the Protection of Navigation in Canadian Navigable Waters (Short Title: Canadian Navigable Waters Act, 2019)

Since time immemorial, the Algonquin or Anishnabeg people have occupied a territory whose heartland is Kitchisibi or Ottawa River watershed. Traditionally, our social, political and economic organization was based on watersheds, which served as transportation corridors for our family land management units. We continue to regard ourselves as ‘keepers of the waterways.’ while continuing to promote ‘seven generations’ worth of responsibilities regarding livelihood security, sacred sites, cultural identity, territorial integrity and biodiversity protection. We have accumulated local, historic and current traditional knowledge and values, customary laws and wisdom that relate to the sustainable environmental management of the lands and waterways we occupy.[101] (p. 7)

how navigation was impeded on not one, but two, locations on our territory since 2013. These cases were not on unprotected waterways, but…were on an actual scheduled [CEAA, 2012 protected] waterway…the Ottawa River, the main highway of our nation. The following examples demonstrate that this new idea of scheduling waterways really provides no protection for navigation under the act…We ask this government, why was our navigation impeded under the Navigation Protection Act on a scheduled waterway?

that various pieces of legislation, including this current proposal [Bill C-69] to combine previous legislation under an impact assessment act, will come together as an assault on Indigenous sovereignty and protection of our land, air, and water. This cumulative policy effect could intentionally strip environmental protections across the country as resource development proceeds and colonialism completes itself.

To be blunt about it, this bill continues the practice of using the power of laws to license the slow and steady genocide of Canada’s Indigenous peoples in the name of the public interest. We are asking you to stop that, here and now, in this bill.

5. Discussion

5.1. A Pan-Indigenous Perspective on the Environment in Canada

our [Cree] worldview…is intended to provide counterpoise to the western concept of the environment that is statistical and quantitative in nature and does not by itself adequately capture the spiritual, cultural and physiological connection of the Moose Cree people to nature and our deep rooted sense of reciprocity with the land, water and animals…We believe that a western-scientific view of the environment is important, but equally valuable, is our unique way of perceiving, knowing and describing our environment.[144] (pp. 4-1 to 4-9)

5.2. A Canadian Pan-Indigenous Perspective on Development in Their Homelands

5.3. Impact Assessment Act

5.3.1. Cultural Sustainability

the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills—as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith—that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage. This intangible cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity.

5.3.2. Discretionary Decision-Making Power and the Public Interest Determination

5.3.3. The Designated Project List

5.3.4. Cumulative Impacts and Regional/Strategic Assessments

5.3.5. Substitution (One Project, One Review)

One thing that puzzles me…why in Bill C-69 we only somewhat carve out the Mackenzie Valley Resource Management Act, completely ignoring all the other First Nation self-government and land claim agreements and impact assessment processes of the north.

5.3.6. Reconciliation

5.4. Canadian Navigable Waters Act

6. Conclusions

6.1. Procedural Justice Aspects

6.2. Distributive Justice Aspects

6.3. The Way Forward

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Themes | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Inherent Rights | “The Wolastoqey are signatories of Peace and Friendship Treaties [i.e., historical treaties], which did not involve or purport to involve the ceding or surrendering of our rights to lands, waters or resources that were traditionally used or occupied. As such, we retain Aboriginal title to our lands, waters and resources. These rights have the potential to be impacted by development, energy regulation and the regulation of navigable waterways. We are entitled to have a say in matters affecting our lands, waters and rights”. (Wolastoqey Nation in New Brunswick [128] p. 1) |

| “Inherently, our lands and waters are part of the Anishinaabe Aki, a vast territory [of unceded land] surrounded by the Great Lakes in North America. For centuries we have relied on our lands and waterways for our ability to exercise our inherent rights under our own system of customary law and governments known as Ona’ken’age’win. This law is based on our mobility on the landscape, the freedom to hunt, gather, and control the sustainable use of our lands and waterways for future generations”. (H. St-Denis, Chief of Wolf Lake First Nation [106] p. 12) | |

| Protection of land and water | “Our traditional perspective and world view that all aspects of the natural world, of which people are part, need to be respected and cared for” (E. Bellegarde, Tribal Chief of Files Hills Qu’Appelle Tribal Council [116] p. 2) |

| “Continue to rely extensively on the resources in our Traditional Territory to feed themselves and their families, maintain their culture, and live as Dene Tha’ people. As Dene Tha’s people, it is our responsibility to take care of the lands and resources within our traditional Territory for current and future generations”. (Dene Tha First Nation [97] p. 1 cover let) | |

| “It’s inherent. It’s within us to be stewards of our land. We’re here to protect it. We’re here to ensure that it’s there for our grandchildren down the road. There is nothing that is going to stop us from protecting it…When things come into our territory, we have to ensure that what is brought there doesn’t leave a lifelong risk that is going to extinguish our being on that territory for my children and grandchildren down the road”. (M. Thomas, Chief of Tsleil-Waututh Nation [110] p. 13) | |

| “Akikodjiwan is a key sacred site to our peoples. Here in Ottawa, it is also known as Chaudière Falls. Akikodjiwan was, and continues to be, a site of prayer, offerings, ritual, and peace. These activities are important work for us as custodians of our waterways and communities, as we redefine and reconcile the interrelationship between our people and the river…a much higher priority must be given to recognize and preserve Akikodjiwan as a key healing point for Algonquin peoples and all cultures here in the national capital region”. (L. Haymond, Chief of Kebaowek First Nation, Wolf Lake First Nation [106] p. 15) | |

| Land and water are not untouched | “Fort McKay’s Traditional Territory comprises over 3.5 million hectares of land… Fort McKay members have used these lands for millennia; lands that are rich in the cultural heritage of the Fort McKay people…Cultural preservation and the transmission of traditional knowledge includes but is not limited to hunting, fishing, trapping and gathering on those [culturally-designated] Reserves and the surrounding lands”. (Fort McKay First Nation [111] pp. 1–4) |

| “Our people have sustained themselves through time immemorial through relying on and taking care of the lands, waters and other aspects of creation”. (Duncan’s First Nation [104] p. 1) | |

| Importance of the environment | “The economies and cultures of Indigenous peoples is inseparably woven with their lands and natural resources and the assessment processes and decision-making authority applicable to industrial projects under IA legislation may have significant impacts on the lands and resources of Indigenous peoples. Land lies at the heart of social, cultural, spiritual, political, and economic life for Indigenous women. The survival of Indigenous communities, their well-being and empowerment depend on their relationship to the land and waters, and the environmental abilities of Indigenous women to transmit their knowledge. Any changes to the environment will directly affect Indigenous women’s and girls’ health, wellbeing, and identity, including national and international policies and regulations on lands and resources…Indigenous women’s relationship to the environment is inseparable from their cultural knowledge, teachings, and identity. Their unique identities are often shaped by time spent, knowledge learned, and gifts given from the land. Environmental degradation and extractive industries influence their ability to be able to carry out their responsibilities to the land or engage in land-based activities integral to their cultural identities. Violence on the land often translates directly into violence against Indigenous women and their ability to carry out and transmit culture. Effectively, denying Indigenous women the equal opportunity to self-determination is allowing systemic cultural genocide to progress”. (Native Women’s Association of Canada [102] p. 7) |

| “The Metis Laws of the Harvest combined with [case law]…and the Canada-MMF Framework Agreement all work together to ensure that the Manitoba Metis Community’s rights are upheld, enabling the Metis to maintain an important aspect of their cultural identity and connection to the land while ensuring the natural environment is protected and species are conserved”. (Manitoba Metis Federation [112] p. 6) | |

| “the Draft Act [ignores the]…indigenous perspectives on this critical resource [i.e., water]...and ultimately views Canada’s waterways as highways that must be regulated, rather than considering the broader values associated with waterways…BC First Nations depend on water-based travel to access places where they harvest traditional resources. The inability, or an impeded ability, to access harvesting areas by water means that fishing rights are degraded and infringed. From an indigenous perspective, the ability to travel by water to access fishing areas is inextricably linked to the health of those waters. Activities that impact navigation and the ability to fish have cascading effects that reverberate through a community: impacting the spirit of the water; the ability of the water to support aquatic and terrestrial species, including plants that are harvested or used in traditional activities; travel through First Nations’ territories; the ability to pass along cultural and ecological knowledge accumulated over generations; and undermining trading and family relationships among First Nations. In failing to recognize this connection the Draft Act inherently limits the scope of engagement and excludes issues and concerns that are critical to the meaningful exercise of Indigenous rights to navigate waterways and otherwise use water”. (First Nations Fisheries Council [140] pp. 2–5) | |

| “We always identify ourselves as to where we’re from. That is our connection to the land and the water, and that’s our jurisdiction. That’s who we are. We’re part of our ancestors”. (Tsleil-Waututh Nation [109] p. 22) |

| Themes | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Consequences of development | “Throughout the 20th century and continuing today, there has been significant industrial development…including open pit and in-situ oil sands mining, uranium mining, sand and gravel mining, forestry, and pulp and paper mills…provincial and federal environmental assessment and protection laws have failed…these activities have degraded the natural environment, reduced or extirpated numerous species of wildlife, brought sickness to our communities, and infringed upon our Treaty and Aboriginal rights…[our] territory is being destroyed, habitat fragmented, species are being lost, watersheds depleted, and water and air contaminated”. (Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation [107] pp. 1–4) |

| “Over the past several decades our Traditional Territory has been subjected to waves of successive development that have heavily impacted our lands, waters, fish and animals that we have a relationship and rely upon. The cumulative impact of agriculture, hydro projects, oil and gas, oil sands, mining, forestry and over hunting and fishing have impacted the ecology of our lands and has made it difficult to impossible for our people to meet their livelihood and cultural needs and exercise their rights”. (Duncan’s First Nation [104] p. 1) | |

| “Today you can no longer take a drink out of the Ottawa River. Agricultural farms using fertilizers and pulp and paper mills and the Chalk River nuclear facility dump toxic compounds without oversight as pollution by dilution into the waterway”. (Kebaowek and Wolf Lake First Nations [101] p. 7) | |

| “Industrial projects in or near Indigenous communities can result in increased rates of violence against women…in the form of physical or sexual violence, but also takes the form of environmental violence…Indigenous peoples tend to have a greater risk of exposure to toxic heavy metals…because of their cultural, economic and spiritual relationships with nature with proximity to industrial waste and other ecological contaminants having a direct impact on health. Indigenous women and children are particularly vulnerable to industrial toxins…[this] constitutes a form of environmental violence that can have serious, potentially fatal, consequences”. (Native Women’s Association of Canada [102] p. 8) | |

| “[M]assive hydroelectric and resource development over the past 40 years…extremely rapid and disruptive cultural, social, and environmental changes. These changes have caused enormous stress on the Cree in terms of our traditional way of life and culture”. (B. Namagoose, Executive Director, Grand Council of the Crees (Eeyou Istchee), [117] p. 3) | |

| “Kichisippi Pimisi (American eel) is considered sacred to the Algonquin people and has been a central part of our culture for thousands of years…Hydroelectric dams have caused a catastrophic decline this culturally significant species in our traditional watershed…The Lake Sturgeon too is a species culturally significant to the Algonquin…also suffered major decline from dams…Fluctuating water levels and unnatural water flows have significantly impacted fish spawning” (Algonquins of Ontario [105] pp. 3–4) | |

| “If you come to our territory, you’ll hear everyone talk about impediments to navigation…Activities that change the flow of rivers is what impacts navigation most heavily in our region…If you want to make a difference to our way of life and inland navigation, fix these provisions…All that is needed is to add a small list of legislative triggers to provide a backstop to the project list”. (M. Lepine, Director, Government and Industry Relations, Mikisew Cree First Nation [133] p. 16) | |

| Not against development | “The fact is that when you’re talking about project development and economic development, our people need to work too, you know” (H. St-Denis, Chief of Wolf Lake First Nation, [106] p. 16) |

| “In fact every one else will benefit from a project except the First Nations peoples that have Aboriginal Title to the lands affected by a project. And yes There maybe a few Aboriginal jobs or a procurement process maybe in place, but when the project has come and gone there is usually no significant changes to First Nations communities affected by a project...There has to be forms of revenue sharing processes brought into place, as everyone else makes money on a project but the people that are directly affected and further to that they loose opportunity to continue to practice their traditional pursuits on the land. In some instances the land or sources of water are destroyed and not available to provide sustenance to the local FN peoples after the project is complete and long gone”. (Peguis First Nation [118] p. 4) | |

| “While we are not opposed to all forms of development…[governments need] to ensure that all developments are sustainable and to ensure that there enough lands of sufficient quantity and quality to sustain our rights, way of life, culture, livelihood and to ensure the health and safety of our people and our friends and neighbours of the Peace River country”. (Duncan’s First Nation [104] p. 1) | |

| “Ensure that Aboriginal peoples have equitable access to jobs, training, and education opportunities in the corporate sector, and that Aboriginal communities gain long-term sustainable benefits from economic development projects…This will require skills-based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism… Benefit from effective and special measures to improve the economic and social condition of Indigenous women and children”. (Native Women’s Association of Canada [102] p. 3) | |

| “Fort McKay is not opposed to oil sands development. We are, in fact, among the most proactive of first nations with respect to oil sands development. Working in the oil sands sector has brought to the first nation and its members opportunity, economic self-sufficiency, stability, and prosperity that are inaccessible to many first nations people across the country, but as I said earlier, Fort McKay is also surrounded by oil sands development…Working with industry to advance shared objectives requires mutual respect and an acknowledgement that Section 35 grants to all first nations the right to continue a way of life. It also demands that we identify the full range of impacts to first nations and take action to mitigate and accommodate our concerns”. (J. Boucher, Chief of Fort McKay First Nation [114] p. 18) | |

| “We occupy and intensively use the entire area of Eeyou Istchee, both for our traditional way of [life]…and trapping, and increasingly, for a wide range of modem economic activities”. (B. Namagoose, Executive Director, Grand Council of the Crees (Eeyou Istchee) [117] p. 3) | |

| Sustainable development | “Nunavik Inuit are not opposed to development. They recognize that large-scale development projects can represent significant economic potential for our regions and our communities. However, we also recognize that even the smallest projects can have significant impacts on the environment and on the Inuit way of life…there is an expectation within our communities that development projects will not be allowed to proceed unless every precaution has been taken to ensure that they are compatible with our understanding and respect for the environment, and that they uphold the maintenance of Inuit livelihoods, traditional practices, and the cultural identity”. (M. O’Connor, Resource Management Coordinator, Resource Development Department, Makivik Corporation [135] p. 5) |

| “Indigenous peoples have a tradition of sustainable, respectful development and use of the land and resources in their traditional territories. For the federal government to fully partner with indigenous peoples, there must be a shift from mitigating the worst negative impacts toward using impact assessment as a planning tool for true sustainability”. (A. Hoyt, Nunatsiavut Government [127] p. 4) | |

| “[P]ractices of sustainability that we have practiced for thousands of years on our territories. Indigenous institutions are essential for future prosperity and participation in evolving targets for sustainability, biodiversity and climate change under agreements to which Canada is signatory”. (Kebaowek and Wolf Lake First Nations [101] pp. 9–10) |

| Section | Relevant Quotes from the Impact Assessment Act (2019) |

|---|---|

| Designation of Physical Activity Minister’s power to designate (9) | (1) The Minister may, on request or on his or her own initiative, by order, designate a physical activity that is not prescribed by regulations made under paragraph 109(b) if, in his or her opinion, either the carrying out of that physical activity may cause adverse effects within federal jurisdiction or adverse direct or incidental effects, or public concerns related to those effects warrant the designation. Factors to be taken into account (2) Before making the order, the Minister may consider adverse impacts that a physical activity may have on the rights of the Indigenous peoples of Canada…recognized and affirmed by Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 as well as any relevant assessment referred to in Section 92, 93 or 95. (2019:13) |

| Decisions Regarding Impact Assessments (16) | (1)…the Agency must decide whether an impact assessment of the designated project is required. Factors (2) In making its decision, the Agency must take into account the following factors: (c) any adverse impact…[on] Section 35 [rights] (2019:16) |

| Factors To Be Considered Factors—impact assessment (22) | (1) The impact assessment of a designated project, whether it is conducted by the Agency or a review panel, must take into account the following factors: (a) the changes to the environment or to health, social or economic conditions and the positive and negative consequences of these changes that are likely to be caused by the carrying out of the designated project… (b) mitigation measures that are technically and economically feasible and that would mitigate any adverse effects of the designated project; (c) the impact that the designated project may have on…Section 35 [rights]… (f) any alternatives to the designated project that are technically and economically feasible and are directly related to the designated project…(l) considerations related to Indigenous cultures raised with respect to the designated project…(q) any assessment of the effects of the designated project that is conducted by or on behalf of an Indigenous governing body and that is provided with respect to the designated project (2019:20–21) |

| Substitution Minister’s power (31) | (1)… the Minister may, on request of the jurisdiction…approve the substitution of that [EA] process for the impact assessment. (2019:25) |

| Impact Assessment by a Review Panel General Rules Referral to review panel (36) | Public interest (1) Within 45 days…a designated project is posted on the Internet site, the Minister may, if he or she is of the opinion that it is in the public interest, refer the impact assessment to a review panel. (2) The Minister’s determination regarding whether the referral…is in the public interest must include a consideration of the following factors…(b) public concerns related to those effects…(d) any adverse impact…[on] Section 35 [rights](2019:28) |

| Decision-Making Minister’s decision (60) | (1) After taking into account the report with respect to the impact assessment of a designated project that is submitted to the Minister…or at the end of the assessment under the process approved under Section 31, the Minister must (a) determine whether the adverse effects within federal jurisdiction—and the adverse direct or incidental effects—that are indicated in the report are, in light of the factors referred to in Section 63 and the extent to which those effects are significant, in the public interest; or (b) refer to the Governor in Council the matter of whether the effects referred to in paragraph (a) are, in light of the factors referred to in Section 63 and the extent to which those effects are significant, in the public interest. (2019:42) |

| Referral to Governor in Council (61) | (1) After taking into account the report with respect to the impact assessment of a designated project that the Minister receives…the Minister, in consultation with the responsible Minister, if any, must refer to the Governor in Council the matter of determining whether the adverse effects within federal jurisdiction—and the adverse direct or incidental effects—that are indicated in the report are, in light of the factors referred to in Section 63 and the extent to which those effects are significant, in the public interest. (2019:42) |

| Governor in Council’s determination (62) | If the matter is referred to the Governor in Council under paragraph 60(1)(b) or Section 61, the Governor in Council must…determine whether the adverse effects…that are indicated in the report are, in light of the factors referred to in Section 63 and the extent to which those effects are significant, in the public interest. (2019:43) |

| Factors—public interest (63) | The Minister’s determination…in respect of a designated project…and the Governor in Council’s determination…in respect of a designated project…must be based on the report with respect to the impact assessment and a consideration of the following factors: (a) the extent to which the designated project contributes to sustainability; (b) the extent to which the adverse effects…are indicated in the impact assessment report in respect of the designated project are significant; (c) the implementation of the mitigation measures that the Minister or the Governor in Council, as the case may be, considers appropriate; (d) the impact that the designated project may have on any Indigenous group and any adverse impact that the designated project may have on the rights of the Indigenous peoples of Canada recognized and affirmed by Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982; and (e) the extent to which the effects of the designated project hinder or contribute to the Government of Canada’s ability to meet its environmental obligations and its commitments in respect of climate change. |

| Conditions—effects within federal jurisdiction (64) | (1) If the Minister determines under paragraph 60(1)(a), or the Governor in Council determines under Section 62, that the effects that are indicated in the report that the Minister or the Governor in Council, as the case may be, takes into account are in the public interest, the Minister must establish any condition that he or she considers appropriate in relation to the adverse effects within federal jurisdiction with which the proponent of the designated project must comply. (2019:44) |

| Decision statement issued to proponent (65) | (1) The Minister must issue a decision statement to the proponent of a designated project…Detailed reasons (2) The reasons for the determination must demonstrate that the Minister or the Governor in Council, as the case may be, based the determination on the report with respect to the impact assessment of the designated project and considered each of the factors referred to in Section 63. (2019:45) |

| Minister’s power—decision statement (68) | (1) The Minister may amend a decision statement, including to add or remove a condition, to amend any condition or to modify the designated project’s description. However, the Minister is not permitted to amend the decision statement to change the decision included in it. (2019:47) |

| Designation of class of projects (88) | (1) The Minister may, by order, designate a class of projects if, in the Minister’s opinion, the carrying out of a project that is a part of the class will cause only insignificant adverse environmental effects. (2019:54) |

| Referral to Governor in Council (90) | (1) If the authority determines that the carrying out of a project on federal lands or outside Canada is likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects, the authority may refer to the Governor in Council the matter of whether those effects are justified in the circumstances…Governor in Council’s decision…(3) When a matter has been referred to the Governor in Council, the Governor in Council must decide whether the significant adverse environmental effects are justified in the circumstances and must inform the authority of its decision. (2019:55) |

| Regional Assessments and Strategic Assessments (92) | Regional assessments—region entirely on federal Lands The Minister may establish a committee—or authorize the Agency—to conduct a regional assessment of the effects of existing or future physical activities carried out in a region that is entirely on federal lands. (2019:55) |

| Strategic Assessments (95) | (1) The Minister may establish a committee—or authorize the Agency—to conduct an assessment. (2019:57) |

| Administration Regulations—Governor in Council (109) | The Governor in Council may make regulations…(a) amending Schedule 1 or 4 by adding or deleting a body or a class of bodies; (b) for the purpose of the definition designated project in Section 2, designating a physical activity or class of physical activities and specifying which physical activity or class of physical activities may be designated by the Minister under paragraph 112(1)(a.2) [designating a physical activity]…(d) varying or excluding any requirement set out in this Act or the regulations as it applies to physical activities to be carried out…(i) on reserves, surrendered lands or other lands that are vested in Her Majesty and subject to the Indian Act (2019:63) |

| Amendment of Schedule 2 (110) | The Governor in Council may, by order, amend Schedule 2 by adding, replacing or deleting a description of lands that are subject to a land claim agreement referred to in Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. (2019:64) |

| Minister’s powers (114) | (1) For the purposes of this Act, the Minister may…(e) if authorized by the regulations, enter into agreements or arrangements with any Indigenous governing body not referred to in paragraph (f) of the definition jurisdiction in Section 2 to (i) provide that the Indigenous governing body is considered to be a jurisdiction for the application of this Act on the lands specified in the agreement or arrangement, and (ii) authorize the Indigenous governing body, with respect to those lands, to exercise powers or perform duties or functions in relation to impact assessments under this Act—except for those set out in Section 16—that are specified in the agreement or arrangement; (2019:87–88) |

| Themes | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Add Waterways | “The Bill should expand protections under the Act to include all navigable waters, not just those on the Schedule. If the Minister decides whether the project interferes with navigation and an approval is required, the Minister wields very broad discretionary power…The only way to preserve, protect, and respect inherent and Treaty rights is to amend this Bill to protect all waterways”. (Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations [95] pp. 6–7) |

| “Add Waterways to the Schedule and Respect Dene Governance and Uses The only way to preserve, protect, and respect Dene rights and protocols is to protect all waterways. This would ensure that the federal government is involved every time a proponent’s work potentially infringes a Dene right of navigability, or other s 35 rights”. (Dene Nation [100] p. 5) | |

| “Further, we continue to disagree with the decision to maintain a Schedule of navigable waters. This was contrary to the recommendation of most Indigenous Groups who made submissions in this process…In our view, all navigable waters are deserving of protection. The listing process, while somewhat clearer, remains entirely discretionary, and puts the onus on the person seeking to protect the waterway to justify its inclusion, rather than requiring proponents or the Minister to justify why a waterway should not be included in the Schedule”. (Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn [123] p. 9) | |

| “CEAA 2012 changes and as it is still today the Feds only have the responsibility of 2 bodies of water in Mb [Manitoba} and 2 major rivers and these are: Lake Manitoba, Lake Winnipeg, the Churchill River and Nelson River. There are 100,000 lakes in Mb not counting all the rivers and streams, First Nations in Mb do not have a good working relationship with the Province when it comes to “First Nations Rights to Water” (Peguis First Nation [118] p. 5) | |

| Discretionary decision-making power | “Bill C-69 remains overly politicized, with the minister making final decisions on the scheduling of waterways or designation of projects, and the cabinet making final project decisions after a full impact assessment process…Prime Minister Trudeau specifically promised to return lost protections to waterways in this country…We are requesting that the act guarantee…it will schedule any waterway that first nations request to be scheduled. Without this amendment, we have little choice but to pursue legal identity for the Ottawa River watershed…in our view all protections have effectively been lost…assessments and decisions be based on the broader scope of indigenous social, ecological, and cultural knowledge”. (H. St-Denis, Chief of Wolf Lake First Nation [106] p. 15) |

| “Overly broad discretion to exempt waters from dumping and dewatering restrictions. The proposed s. 24 allows the Governor in Council to make orders exempting any water from the application of ss. 21 to 23. The only limit on this discretion is that it be in the undefined “public interest”. This does not give sufficient guidance or protection for First Nations…“Public interest” does not include protection of Section 35 rights… In several places, the Minister or the Governor in Council may make decisions or take action if it is in the “public interest”. If “public interest” is not defined to make reference to Section 35 rights, then there is a concern that Section 35 rights will not be considered at all when these decisions are made”. (Atlantic Policy Congress of First Nations’ Chiefs Secretariat [98] pp. 6–7) | |

| “All First Nation Waterways Must Be Formally Recognized, Included, and Protected The Dene Nation has stressed throughout the legislative review process that Canada must respect and acknowledge that water is the richness of the North and of Denendeh. We submit that the discretionary powers of the Minister should be informed by the Dene Nations and ultimately limited…We suggest that regulatory instruments must require the Minister to consider Indigenous rights and uses of waterways when assessing whether a project may interfere with navigation”. (Dene Nation [100] p. 5) | |

| “the CNWA continues to provide too much unfettered discretion to the Minister to make a number of critical determinations, including designating both major works and a minor works. Such a determination should not be purely discretionary”. (Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn [123] p. 10) | |

| “It should be explicitly specified that the public interest requires the protection of Section 35 rights…There continues to be little direction on how the Minister or Governor in Council exercises discretion under the CNWA. Section 28(1)(g.1) allows the Governor in Council to make regulations “excluding any body of water from the definition of navigable water in Section 2”. Under this provision the Governor in Council can make regulations to exclude any waterway as a navigable water. Section 24 also allows the Governor in Council to make orders exempting any water from the application of Sections 21 to 23. The only limit on this discretion is that it be in the undefined “public interest”. These powers are exercised without any public or Indigenous consultation or Parliamentary oversight”. (Wolastoqey Nation in New Brunswick [128] pp. 8–9) |

References

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future. Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji, S.R.J. Indigenous Environmental Justice and Sustainability: What Is Environmental Assimilation? Sustainability 2021, 13, 8382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, J.F. The Indian Act: An historical perspective. Can. Parl. Rev. 2002, summer, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gradual Civilization Act. An Act to Encourage the Gradual Civilization of the Indian Tribes in this Province, and to Amend the Laws Respecting Indians. CAP. XXVI. Province of Canada, Canada West. 1857. Available online: https://signatoryindian.tripod.com/routingusedtoenslavethesovereignindigenouspeoples/id10.html (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Brownlie, R.J. ‘A better citizen than lots of white men’: First Nations enfranchisement—An Ontario case study. Can. Hist. Rev. 2006, 87, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, C. Reconstituting Canada: The enfranchisement and disenfranchisement of ‘Indians’ circa 1837-1900. Univ. Tor. Law J. 2019, 69, 497–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constitution Act. A Consolidation of the Constitution Acts 1867 to 1982, Department of Justice Canada, Consolidated as of 1 January 2013; Public Works and Government Services Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1982. Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/pdf/const_e.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Cannon, M. Revisiting histories of legal assimilation, racialized injustice, and the future of Indian status in Canada. Aborig. Pol. Res. Consort. Int. 2007, 97, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, B. Gender, race, and the regulation of Native identity in Canada and the United Sates: An overview. Hypatia 2003, 18, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.W. American Indian identity and blood quantum in the 21st century: A critical review. J. Anthro. 2011, 2011, 549521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruhan, P. CDIB: The role of the certificate of degree of Indian blood in defining Native American legal identity. Am. Indian Law J. 2018, 6, 169–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1, Origins to 1939; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal, S.W. A framework for Indigenous adoptee reconnection: Reclaiming language and identity. Can. J. New Sch. Ed. 2016, 7, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, R. The Indigenous child removal system in Canada: An examination of legal decision-making and racial bias. First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 2016, 11, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, L.; Dubinsky, K. The politics of history and the history of politics. Am. Indian Quart. 2013, 37, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Introduction; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015.

- Nishiiyuu Council of Elders (Undated). “What You Do to Eeyou Istchee (Our Land), You Do to Eeyouch (Our People)”. Available online: https://archives.bape.gouv.qc.ca/sections/mandats/uranium-enjeux/documents/MEM26.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Treaty No. 9 (1905); Queen’s Printer Stationery: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1964; Available online: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100028863/1581293189896 (accessed on 2 October 2021).

- James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. 1975. Available online: http://www.naskapi.ca/documents/documents/JBNQA.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Far North Act, 2010. S.O. 2010, c. 18. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/10f18?search=Far+North+act (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Mining Amendment Act, 2009. S.O. 2009, c. 21. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/s09021 (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- COVID-19 Economic Recovery Act, 2020. S.O. 2020, c.18. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/s20018 (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Bill C-69 (An Act to Enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to Amend the Navigation Protection Act and to Make Consequential Amendments to Other Acts, 2018). Available online: https://www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/bill/c-69/first-reading (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Bill C-69 (An Act to Enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to Amend the Navigation Protection Act and to Make Consequential Amendments to Other Act. S.C. 2019, c.28). Impact Assessment Act (2019) S.C. 2019, c. 28, s. 1. Canadian Energy Regulator Act (2019) S.C. 2019, c. 28, s. 10. Canadian Navigable Waters Act (2019) R.S., 1985, c. N-22, s. 1; 2012, c. 31, s. 316; 2019, c. 28, s. 46. Available online: https://www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/bill/c-69/royal-assent (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (2012) S.C. 2012, c. 19, s. 52. Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-15.21/index.html (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Commission for Racial Justice. Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States; United Church of Christ: Cleveland, OH, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard, R.D.; Mohai, P.; Saha, R.; Wright, B. Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty 1987–2007; United Church of Christ: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Environmental Justice. 2021. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Scott, D.N. What is environmental justice? Osgoode Leg. Stud. Res. Pap. 2014, 10. Research Paper No. 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, R.D. Access to Environmental Justice in Canada: The Road Ahead; Canadian Environmental Law Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://cela.ca/access-to-environmental-justice-in-canada-the-road-ahead/ (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- McGregor, D.; Whitaker, S.; Sritharan, M. Indigenous environmental justice and sustainability. Curr. Opin. Enviro. Sust. 2020, 43, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King George III of England. Royal Proclamation of 1763; King’s Printer, Mark Baskett in London: London, UK, 1763; Available online: https://exhibits.library.utoronto.ca/items/show/2470 (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Tsuji, L.J.S.; Tsuji, S.R.J. Development on Indigenous Homelands and the Need to Get Back to Basics with Scoping: Is there Still “Unceded” Land in Northern Ontario, Canada, with respect to Treaty No. 9 and its Adhesions? Int. Indig. Policy J. 2021, 12, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, S.R.J.; Tsuji, L.J.S. Treaty No. 9 and the Question of “Unceded” Land South of the Albany River in Subarctic Ontario, Canada. Arctic 2021, 74, 239–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (Undated) Pre-1975 Treaties (Historic Treaties). Available online: https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/f281b150-0645-48e4-9c30-01f55f93f78e (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Rees, W.E. EARP at the Crossroads: Environmental Assessment in Canada. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1980, 1, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency. Canadian Environmental Assessment Act: An Overview; Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/impact-assessment-agency/services/policy-guidance/canadian-environmental-assessment-act-overview.html (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Kirchhoff, D.; Gardner, H.L.; Tsuji, L.J.S. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012, and Associated Policy: Implications for Aboriginal Peoples. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2013, 4, 1. Available online: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/iipj/vol4/iss3/1/ (accessed on 18 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Kwasniak, A. Harmonization, Substitution, Equivalency, and Delegation in Relation to Federal and Provincial/Territorial Environmental Assessment; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D. Delivering the Future That Today’s Canadians Want and Tomorrow’s Canadians Need: Key Amendments to Strengthen Bill C-69, the Impact Assessment Act; Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability, University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barrell, R.; Davis, E. The Evolution of the Financial Crisis of 2007-8. Nat. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2008, 206, 5–14. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/docview/219414635/ (accessed on 18 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.K. Environmental impact assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, S.R.J. Economic Recovery in Response to Worldwide Crises: Fiduciary Responsibility and the Legislative Consultative Process with Respect to Bill 150 (Green Energy and Green Economy Act, 2009) and Bill 197 (COVID-19 Economic Recovery Act, 2020) in Ontario, Canada. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Bill C-38. An Act to Implement Certain Provisions of the Budget Tabled in Parliament on March 29 2012 and Other Measures. Short Title: Jobs, Growth and Long-Term Prosperity Act. 2012. Available online: https://www.parl.ca/LegisInfo/en/bill/41-1/C-38 (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Bill C-45. A Second Act to Implement Certain Provisions of the Budget Tabled in Parliament on March 29 2012 and Other Measures. Short Title: Jobs and Growth Act, 2012. 2012. Available online: https://www.parl.ca/LegisInfo/en/bill/41-1/C-45 (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Doelle, M. CEAA 2012: The End of Federal EA as We Know It? J. Environ. Law Pract. 2012, 24, 1–17. Available online: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2104336 (accessed on 18 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.B. In full retreat: The Canadian government’s new environmental assessment law undoes decades of progress. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kichhoff, D.; Tsuji, L.J.S. Reading Between the Lines of the ‘Responsible Resource Development’ Rhetoric: The Use of Omnibus Bills to ‘Streamline’ Canadian Environmental Legislation. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2014, 32, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRobert, D.; Tennent-Riddell, J.; Walker, C. Ontario’s green economy and green energy act: Why well-intentioned law is mired in controversy and opposed by rural communities. RELP 2016, 7, 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Environmental Assessment Act [CEAA]. 1992. (S.C. 1992, c. 37). Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-15.2/ (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Regulations Designating Physical Activities. (SOR/2012-147); Minister of Justice: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012; Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/SOR-2012-147.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Mascher, S. Written Submission on the Proposed Impact Assessment Act (IAA) to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H.L.; Tsuji, S.R.J.; McCarthy, D.D.; Whitelaw, G.S.; Tsuji, L.J.S. The Far North Act (2010) Consultative Process: A New Beginning or the Reinforcement of an Unacceptable Relationship in Northern Ontario, Canada? Int. Indig. Pol. J. 2012, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massicotte, M.G.; Farmer, D. Canada: CEAA 2012–Significant Amendments Made to the Regulations Designating Physical Activities. Available online: http://www.mondaq.com/canada/x/273806/Oil+Gas+Electricity/CEAA+2012+Significant+Amendments+Made+To+The+Regulations+Designating+Physical+Activities (accessed on 5 February 2014).

- Government of Canada’s Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development. Statutory Review of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act: Protecting the Environment, Managing Our Resources; Report of the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development. (Mark Warawa, M.P. Chair). March 2012. 41st Parliament, 1st Session; House of Commons, Public Works and Government Services Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2012/parl/XC50-1-411-01-eng.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Liberal Party of Canada. Dissenting Opinion by the Liberal Party of Canada on the Report of the Statutory Review of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA). In Statutory Review of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act: Protecting the Environment, Managing Our Resources; Report of the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; Liberal Party of Canada, Public Works and Government Services Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012; pp. 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- New Democratic Party of Canada. Dissenting Report from the Official Opposition New Democratic Party on the Seven-year review of CEAA. In Statutory Review of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act: Protecting the Environment, Managing Our Resources; Report of the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; New Democratic Party of Canada, Public Works and Government Services Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012; pp. 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Macklem, P. The Impact of Treaty 9 on natural resource development in Northern Ontario. In Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada: Essays on Law, Equity, and Respect for Difference; Asch, M., Ed.; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1997; pp. 97–132. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H.L.; Kirchhoff, D.; Tsuji, L.J.S. The streamlining of the Kabinakami River hydroelectric project Environmental Assessment: What is ‘duty to consult’ with other impacted Aboriginal communities when the co-proponent of the project is an Aboriginal community. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2015, 6, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.; Macklem, P. From consultation to reconciliation: Aboriginal rights and the Crown’s duty to consult. Can. Bar Rev. 2000, 79, 252–266. [Google Scholar]

- Bankes, N. The Duty to Consult in Canada Post-Haida Nation. Arct. Rev. Law Politics 2020, 11, 256–279. [Google Scholar]

- Rio Tinto Alcan Inc. v. Carrier Sekani Tribal Council (2010) SCC 43. Available online: https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/7885/index.do (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Bankes, N. The Duty to Consult and the Legislative Process: But What About Reconciliation? ABlawg.ca. 2016. Available online: https://ablawg.ca/2016/12/21/the-duty-to-consult-and-the-legislative-process-but-what-about-reconciliation/ (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Treaty No. 8. 1899. Available online: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100028813/1581293624572 (accessed on 2 October 2021).

- Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada (Govenor General in Council) 2018 SCC 40. Available online: https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/17288/index.do (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- SSC. Supreme Court of Canada Case in Brief Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada (Governor General in Counci). 2018. Available online: https://www.scc-csc.ca/case-dossier/cb/37441-eng.aspx (accessed on 18 January 2020).

- Gelinas, J.; Horswill, D.; Northey, R.; Renée, P. Building Common Ground. A New Vision for Impact Assessment in Canada. The Final Report of the Expert Panel for the Review of Environmental Assessment Processes; Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017.

- Government of Canada. Environmental and Regulatory Reviews Discussion Paper; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017.

- United Nations General Assembly. United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, 15 December 1972. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/stockholm1972 (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Gibson, R.; Hassan, S. Sustainability Assessment: Criteria and Processes; Earthscan: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- World Public Meeting on Culture. September 2002. Available online: https://www.agenda21culture.net/2002-2004 (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Agenda 21: Earth Summit: The United Nations Programme of Action from Rio, 1993 UNEP. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- United Cities and Local Governments. (2002–2004). Agenda 21 for Culture. Available online: https://www.agenda21culture.net/sites/default/files/files/documents/multi/ag21_en.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Wright, D.V. Public Interest versus Indigenous Confidence: Indigenous Engagement, Consultation, and ’Consideration’ in the Impact Assessment Act. SSRN (Formerly Known as Social Science Research Network). 2020. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3692839 (accessed on 18 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hunsberger, C.; Froese, S.; Hoberg, G. Toward ‘good process’ in regulatory reviews: Is Canada’s new system any better than the old? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 82, 106379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navigation Protection Act R.S., 1985, c. N-22, s. 1; 2012, c. 31, s. 316. 2012. Available online: https://tc.canada.ca/en/corporate-services/acts-regulations/navigation-protection-act-rs-1985-c-n-22 (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- IAAC. Impact Assessment Agency of Canada. Impact Assessment Act and CEAA 2012 Comparison. 2020. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/impact-assessment-agency/services/policy-guidance/impact-assessment-act-and-ceaa-2012-comparison.html (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Government of Canada. Governor in Council and Ministerial Appointments. 2021. Available online: https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/careers-carrieres.nsf/eng/00954.html (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Statistics Canada. Highlights of Canada’s Geography. 2021. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-402-x/2011000/chap/geo/geo-eng.htm (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Tsuji, L.J.S.; Gomez, N.; Mitrovica, J.X.; Kendall, R. Post-Glacial Isostatic Adjustment and Global Warming in Sub-Arctic Canada: Implications for Islands of the James Bay Region. Arctic 2009, 62, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Statistics Canada. The Social and Economic Impacts of COVID-19: A Six-month Update. Catalogue No. 11-631-x. 2020. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-631-x/11-631-x2020003-eng.htm (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Statistics Canada. Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census; Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 98-404-X2016001. Data Products, 2016 Census; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-PR-Eng.cfm?TOPIC=9&LANG=Eng&GK=PR&GC=35 (accessed on 27 December 2019).

- Statistics Canada and the Assembly of First Nations. A Snapshot: Status First Nations People in Canada; Catalogue Number: 41200002-2021001; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021.

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Maps of Inuit Nunangat (Inuit Regions of Canada). 2021. Available online: https://www.itk.ca/maps-of-inuit-nunangat/ (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- O’Donnell, V.; LaPointe, R. Response Mobility and the Growth of the Aboriginal Identity Population, 2006–2011 and 2011–2016; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019.

- Statistics Canada. Canada’s Population Estimates, Third Quarter 2019; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019.

- Tsuji, L.J.S.; Ho, E. Traditional Environmental Knowledge and Western Science: In Search of Common Ground. Can. J. Nat. Stud. 2002, 22, 327–360. Available online: http://www3.brandonu.ca/cjns/22.2/cjnsv.22no.2_pg327-360.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Eckert, L.E.; Claxton, N.X.; Owens, C.; Johnston, A.; Ban, N.C.; Moola, F.; Darimont, C.T. Indigenous Knowledge and Federal Environmental Assessments in Canada: Applying Past Lessons to the 2019 Impact Assessment Act. FACETS 5: 67–90. 2020. Available online: https://www.facetsjournal.com/doi/10.1139/facets-2019-0039 (accessed on 18 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Mikisew Cree First Nation. Written Brief Regarding the Impact Assessment Act (IAA) and the Canadian Navigable Waters Act (CNWA) in Bill C-69; Mikisew Cree First Nation: Fort McMurray, AB, Canada, 2018.

- Lower Fraser Fisheries Alliance. Brief to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development Regarding Bill C-69, an Act to Enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to Amend the Navigation Protection Act and Make Consequential Amendments to Other Acts; Lower Fraser Fisheries Alliance: Abbotsford, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Okanagan Nation Alliance. Submissions to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development (the Committee) on: “Bill C-69, an Act to Enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to Amend the Navigation Protection Act and to Make Consequential Amendments to Other Acts” (Bill C-69); Okanagan Nation Alliance: Westbank, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Teegee, T. No. 103 Presentation by the Regional Chief, British Columbia Assembly of First Nations, BC First Nations Energy & Mining Council to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; ENVI. 42nd Parliament, 1st Session; Evidence; House of Commons, Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/ENVI/meeting-103/evidence#T1240 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations. Written Submission on Bill C-69; Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Coastal First Nations. Submissions to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development (the Committee) on: “Bill C-69, an Act to Enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to Amend the Navigation Protection Act and to Make Consequential Amendments to Other Acts” (Bill C-69); Coastal First Nations: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dene Tha First Nation. Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development (Committee) Study on Bill C-69, an Act to Enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to Amend the Navigation Protection Act and to Make Consequential Amendments to Other Acts (Bill C-69); Dene Tha First Nation: Chateh, AB, Canada, 2018.

- Atlantic Policy Congress of First Nations Chiefs Secretariat. Written Submissions to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development on Bill C-69; Atlantic Policy Congress of First Nations Chiefs Secretariat: Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Assembly of First Nations. Submission to House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development on Bill C-69; British Columbia Assembly of First Nations: Prince George, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dene Nation. Written Submission on Bill C-69, an Act to Enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to Amend the Navigation Protection Act and to Make Consequential Amendments to Other Acts Introduction; Dene National/Assembly of First Nations Office (NWT): Yellowknife, NT, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kebaowek and Wolf Lake First Nations. Kebaowek and Wolf Lake First Nations’ Submission on the Impact Assessment Act, Canadian Energy Regulator, and Navigable Waters Act (Bill C-69) to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; Kebaowek and Wolf Lake First Nations: Kebaowak, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Native Women’s Association of Canada. Bill C-69: Impact Assessment Legislation and the Rights of Indigenous Women in Canada; Native Women’s Association of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Assembly of First Nations. Study on Impact Assessment Act, Canadian Energy Regulator, and Navigable Waters Act (Bill C-69); Assembly of First Nations: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan’s First Nation. Duncan’s First Nation Comments Related to Bill C-69, an Act to Enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to Amend the Navigation Protection Act and to Make Consequential Amendments to Other Acts; Duncan’s First Nation: Brownvale, AB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Algonquins of Ontario. Bill C-69–Submission of Comments; Algonquins of Ontario: Pembroke, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- St-Denis, H. No. 107 Presentation by the Chief of Wolf Lake First Nation to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; ENVI. 42nd Parliament, 1st Session; Evidence; House of Commons, Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://parlvu.parl.gc.ca/Harmony/en/PowerBrowser/PowerBrowserV2/20180425/-1/29162?Embedded=true&globalstreamId=20&startposition=5742&viewMode=3 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation. Bill C-69: An Act to Enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to Amend the Navigation Protection Act and to Make Consequential Amendments to Other Acts; Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation: Fort Chipewyan, AB, Canada, 2018.

- Haymond, L. No. 107 Brief by Chief of Kebaowek First Nation, Wolf Lake First Nation to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; ENVI. 42nd Parliament, 1st Session; Evidence; House of Commons, Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/ENVI/Brief/BR9836198/br-external/AlgonquiFirstNationOKebaowekAndWolfLake-e.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Tsleil-Waututh Nation. No. 106 Presentation by the Tsleil-Waututh Nation to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; ENVI. 42nd Parliament, 1st Session; Evidence; House of Commons, Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/ENVI/meeting-106/evidence#T1340 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Thomas, M. Tsleil-Waututh Nation Written Submission Regarding Bill C-69; Tsleil-Waututh Nation: North Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fort McKay First Nation. Fort McKay First Nation Submission to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development, Study of Bill C-69; Fort McKay First Nation: Fort McMurray, AB, Canada, 2018.

- Manitoba Metis Federation. Bill C-69 Comments–Submission by the Manitoba Metis Federation; Manitoba Metis Federation: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cold Lake First Nations Lands and Resources, Consultation Department. Bill C-69, an Act to Enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to Amend the Navigation Protection Act and to Make Consequential Amendments to Other Acts; Cold Lake First Nations Lands and Resources, Consultation Department: Cold Lake, AB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, J. No. 103 Presentation by the Chief of Fort McKay First Nation to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; ENVI. 42nd Parliament, 1st Session; Evidence; House of Commons, Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/ENVI/meeting-103/evidence#T1245 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- The First Nations Major Projects Coalition. Submission to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; The First Nations Major Projects Coalition: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bellegarde, E. Submission of Brief and Addenda for Request of the File Hills Qu’ Appelle Tribal Council to Appear before Standing Committee Studying Bill C-69; Tribal Chief of Files Hills Qu’Appelle Tribal Council: Fort Qu’Appelle, SK, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Namagoose, B. No. 104 Presentation by the Executive Director, Grand Council of the Crees (Eeyou Istchee) to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; ENVI. 42nd Parliament, 1st Session; Evidence; House of Commons, Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://parlvu.parl.gc.ca/Harmony/en/PowerBrowser/PowerBrowserV2/20180418/-1/29093?Embedded=true&globalstreamId=20&startposition=689&viewMode=3 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Peguis First Nation. Untitled Submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; Mike Sutherland, Director Peguis Consultation & Special Projects Unit: Peguis, MB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R. No. 107 Presentation by the Chief of West Moberly First Nations to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; ENVI. 42nd Parliament, 1st Session; Evidence; House of Commons, Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: http://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/ENVI/meeting-107/evidence#T1720 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Crey, E. No. 103 Presentation by Indigenous Co-Chair, Indigenous Advisory and Monitoring Committee for the Trans Mountain Pipelines and Marine Shipping to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; ENVI. 42nd Parliament, 1st Session; Evidence; House of Commons, Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/ENVI/meeting-103/evidence#T1340 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Darling, K. No. 106 Presentation by the General Counsel of the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; ENVI. 42nd Parliament, 1st Session; Evidence; House of Commons, Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/ENVI/meeting-106/evidence#T1115 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Inuvialuit Regional Corporation and Inuvialuit Game Council. Brief to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development regarding Bill C-69 an Act to Enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to Amend the Navigation Protection Act and to Make Consequential Amendments to Other Acts; Inuvialuit Regional Corporation and Inuvialuit Game Council: Inuvik, NT, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn. A Submission from Mi’gmaw’el Tplu’taqnn Inc.; Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn: Eel Ground, NB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mainville, S. The Ghost of the Harper OmniBus Legislation Continues on with Bill C-69. The Ghost of the Harper OmniBus Legislation Continues on with Bill C-69-OKT | Olthuis Kleer Townshend LLP. 2018. Available online: oktlaw.com (accessed on 25 July 2021).