Abstract

Livestock have strong empowerment potential, particularly for women. They offer millions of women in the Global South the opportunity to provide protein-rich foods for home consumption and sale. Livestock provide women with income and opportunities to expand their livelihood portfolios and can strengthen women’s decision-making power. Fully realizing livestock’s empowerment potential for women is necessary for sustainable livestock development. It requires, though, that gender-equitable dynamics and norms are supported in rural communities. We draw on 73 village cases from 13 countries to explore women’s experiences with livestock-based livelihoods and technological innovations. Our analysis follows a gender empowerment framework comprised of four interdependent domains—recognition of women as livestock keepers, access to resources, access to opportunities, and decision making as a cross-cutting domain—which must come together if women are to become empowered through livestock. We find improved livestock breeds and associated innovations, such as fodder choppers or training, to provide significant benefits to women who can access these. This, nonetheless, has accentuated women’s double burdens. Another challenge is that even as women may be recognized in their community as livestock keepers, this recognition is much less common among external institutions. We present a case where this institutional recognition is forthcoming and illuminate the synergetic and empowering pathways unleashed by this as well as the barriers that remain.

1. Introduction

Livestock have strong potential for women’s empowerment. Women and girls can find it easier to access and control livestock compared to resources such as land and machinery [1,2,3]. Livestock can provide women with income and the opportunity to expand their livelihood portfolios and decision-making power [4]. They enable women to provide protein-rich foods for home consumption and sale [5] and in some contexts constitute assets that women can claim in cases of widowhood, separation, divorce, or abandonment [6]. Given that women are the majority of poor livestock keepers in low- and middle-income countries [7], only by supporting their empowerment can livestock development be sustainable.

However, in many rural communities, long-standing gender norms shape how livestock are managed and their benefits shared among household members, often in ways that disadvantage women and girls [8]. Norms around which species can be controlled by women (often small livestock such as poultry, guinea pigs, and goats) and by men (often larger species such as camels and cattle) frequently limit the assets women can accumulate [4]. In some places, cultural norms proscribe women from ploughing, thus hampering their ability to farm independently [6,9]. Norms governing access to land and fodder in many locations restrict women’s ability to develop their livestock holdings [10,11].

Fully realizing the empowerment potential of livestock for women requires that gender-equitable dynamics and norms are supported, and that interventions purposively develop and implement multiple interlocking strategies to empower women [2]. Well-meaning interventions addressing one aspect of gender inequality but failing to consider another can founder, particularly those that reproduce existing norms. For instance, training women in fodder production to alleviate the time they spend gathering feed can misfire if only men control and are trained in livestock marketing, thus securing the benefits of the improved forage provided by women [12].

While the body of evidence on women’s empowerment and livestock is growing, much still needs to be understood about the ways in which the two are interlinked: ‘can livestock provide empowering opportunities for women? How?’ Understanding the role gender norms play in the link between livestock and women’s empowerment is equally important because only by addressing the root causes of gender-based disadvantage (i.e., gender norms) can sustainable change towards gender-equitable livestock development be achieved. The overwhelming reliance on household-level data makes it difficult to answer questions around the benefits, use and accumulation of resources [13]. We contribute to closing these research gaps through collecting contextual data at the individual level whereby we look at individuals’ agency and how it is shaped by local norms and opportunities.

In this paper, we assess the ways in which female and male respondents reported livestock innovations to affect women’s empowerment, and how gender norms can influence the empowerment potential of these innovations for women. We explore data from 73 community case studies spanning 13 countries. The cases are part of the GENNOVATE study, which examined relationships between agency, gender norms, and agricultural innovation [14]. In particular, we examine data from 36 of these communities where improved livestock breeds, or an associated livestock innovation, emerged as one of the two most important innovations for the livelihoods of women and men (Top Two) compared to all agricultural innovations introduced in the area within the past five-to-ten years. We complement the cross-case perspective with a case study from Rajasthan for a deeper contextual analysis of local innovation processes. This data is powerful in helping us address our research question because: 1. livestock emerged among the most important agriculture innovations, unsolicited; 2. the large geographical span of the case studies allows both descriptive statistics across many countries and in-depth evidence on specific case studies.

The article is constructed as follows. We introduce our analytic framework followed by materials and methods. In the results, we first discuss the prevalence of Top Two livestock innovations by gender. We then organize our results according to the domains outlined in the analytic framework. To illustrate the dynamics within and across domains, for each domain we provide comparative analysis from across the cases followed by insights from the Rajasthan case. In the discussion, we argue that women’s empowerment through livestock innovations is contingent upon interdependent factors which relate to recognition, access to resources, the provision of opportunities, and decision-making capacities.

2. Analytic Framework

Empowerment can be experienced in many ways and involves collective as well as individual processes. These processes are affected by social norms and involve relational, multi-level, and multi-directional processes of change [15]. Empowerment processes embody relations of power and how power is created, used, and experienced [16,17]. In this article, we are interested in empowerment understood as the process by which an individual acquires the capacity for self-determination. Self-determination is intrinsic to living the life that each one of us has reason to value [18]. This definition of empowerment emphasizes the agency of each individual in defining their own aspirations and pathways. While it provides a universal framework to conceptualize empowerment, it also accommodates the multiplicity of individual pathways and aspirations for self-determination.

How do we know if individuals are engaged in a process of empowerment? There have been considerable efforts to operationalize the concept of empowerment, and, in some cases, to create measurable domains which can be assessed “objectively” [1,19]. The Women’s Empowerment in Livestock Index (WELI) [1], for example, like the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) [19], measures women’s empowerment across three dimensions of agency (intrinsic, instrumental, and collective). Given our aim to explore the ways in which livestock innovations were reported to affect women’s empowerment, we were interested in looking beyond an exclusive focus on agency and its quantitative assessment and, rather, adopt a broad conceptualization of empowerment that would allow us to capture it as a whole process of change (we do compare our findings to WELI results from Tanzania, where possible—see Section 5). The framework by Johnson et al. (2018) [20] on projects’ ability to ‘reach’, ‘benefit’, and ‘empower’ women was also considered not adequate to capture how the process of change in empowerment through livestock can unfold. We therefore built our conceptual framework on key broad components that are necessary for empowerment—as self-determination—to actualize. Sachs and Santarius (2007) [21] operationalize the concept of self-determination through three interdependent and mutually enforcing domains: recognition, access to resources, and access to opportunities. We adopt these domains and add decision making as a fourth, cross-cutting domain (see also [22]).

Recognition refers to acknowledgement by others of the roles each person takes, or aspires to take, in society. Recognition entails an individual’s capacity to conceive of, and freely enact, their preferred roles and identities, but also demands acknowledgement by others of a person’s preferred roles and identities and their wish to enact them.

Resources, or capital (financial, physical, human, social, political, natural, or cultural), are required for individuals to realize their desired roles and identities.

Opportunities are needed for individuals to make use of the resources they can access. Examples include jobs and training opportunities.

Decision making refers to individuals’ ability to take, and act upon, their own decisions. This allows them to achieve recognition of their aspirations, access resources, and to seize opportunities. The relationship between the domains is not necessarily linear. Women’s decision-making power cuts across and links together the domains.

Next, we present and illustrate each domain by drawing on gender and livestock literature.

2.1. Domain 1: Livestock and Recognition

The majority of researchers, rural advisory services (RAS), livestock breeders, private sector players, and policy makers fail to sufficiently recognize women as livestock keepers [22,23]. Women’s roles and responsibilities in livestock (and in agriculture more generally) are frequently subsumed under the identity of ‘helpers’ [24,25,26]. However, women are often strongly involved in livestock management and have interests in the benefits derived from selling livestock and related products or in using them within the home [27,28]. Not recognizing women as livestock keepers can have important negative implications for women. A case study from Central Nicaragua shows that women are strongly involved in cattle care and often jointly own cattle with their husbands [29]. Yet, women are not conceptualized by the RAS, or by their husbands, as ‘the livestock keepers’, only men are. Therefore, women and other family members are not formally invited to livestock training events (ibid.). Moreover, due to their close contact with cattle, women frequently are the ones who know when a cow is in heat. Yet, providers of artificial insemination (AI) mostly liaise with men only and insemination often fails because men fail to inform the inseminator on time (ibid.). Women also tend to sick animals; however, because they are not recognized as livestock keepers, their greater exposure to zoonotic diseases tends to be overlooked. The lack of recognition of women’s livestock roles and knowledge and the exclusive targeting of men can, therefore, dampen women’s decision-making capacity, limit the productivity of livestock livelihoods, and endanger women’s health.

2.2. Domain 2: Livestock and Resources

The degree of recognition of women as livestock farmers has implications for their ability to lay claim to the resources, or capitals, needed to sustain and develop livestock effectively. Flora and Flora (2008) [30] define “capital” as any type of resource which can be invested with the purpose of creating new resources. These include natural, cultural, human, social, financial, political, and physical capitals. People invest in capitals, creating flows which result in interactions and feedback loops between the capitals [31]. In contexts where livestock is vital to the local economy, access and control to livestock resources by women can result in their empowerment by increasing their bargaining power, ability to accumulate assets, and access to animal source foods that they use mostly to benefit their children [32,33]. Yet, women are disadvantaged in livestock ownership versus men in that men generally control larger animals and cross-bred or exotic breeds; women control smaller animals and local breeds that are of lesser value [4]. Five community case studies conducted in Ethiopia on goat and sheep value chains showed that women’s and men’s access to various capitals varied due to differences in cultural norms among communities [31]. Access was gendered, with women—regardless of community—generally experiencing lower access to all capitals than men and thus a lower ability to mobilize the capitals synergistically to their advantage. Male household headship provides men with a stronger say over livestock use and sales (apart from goat milk which is indisputably under women’s control). The situation in these Ethiopian communities is not static, however. Government and NGO interventions are successfully increasing women’s access to capitals, including improved breeds (natural capital), improved knowledge (human capital), and a stronger voice (political capital) (ibid.) with potentially significant implications for women’s empowerment.

2.3. Domain 3: Livestock and Opportunities

For millions of livestock keepers across the Global South, livestock provide key opportunities to improve household nutrition (by producing protein-rich foods), obtain employment, participate in markets, and pursue sustainable livelihoods [34,35]. However, such opportunities vary across and within communities and households. Intersections between gender and other social categories, for example, ethnicity, generation, or caste, may impede women’s (and men’s) abilities to access and build on opportunities. A case study on dairy cooperatives in Bihar, India, showed that Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe women members found themselves unable to benefit from training courses or to participate effectively in cooperative governance structures due to caste-based discrimination. Higher caste women occupied decision-making roles and participated in training courses. Ultimately, the cooperative and its benefits were controlled by the husbands of these women [36]. Numerous examples show that, where livestock provide significant income-generating opportunities, male capture of these opportunities and the related benefits may contribute to women’s disempowerment [37].

In other cases, women capitalize on opportunities more effectively. In a small ruminant project in Ethiopia, for example, women’s improved social capital through cooperative membership and improved human capital through livestock training programs enabled them to argue successfully for improved breeds and greater support from the RAS [31]. Dairy cooperatives were also shown to contribute to women’s empowerment in Kenya [38].

2.4. Domain 4: Livestock and Decision Making

Women and men may have different preferences for livestock species and traits, different reasons for raising livestock, and different constraints and opportunities to access and benefit from livestock or livestock services [23]. Women’s empowerment through their livestock activities requires that both spouses can shape decisions over their aspirations for the livestock enterprise, including the resources to invest in the enterprise, which agricultural innovations or other opportunities need to be adopted, and how benefits are to be distributed.

The extent of women’s decision making over livestock and related products changes over time and by size of enterprise. A study of pigkeeping in Vietnam found that women now take many more decisions than in the past, primarily due to male outmigration [39], which has made the gender division of labor in livestock care more flexible. Yet, women’s decision-making power declines with the size of the enterprise. In large enterprises with more than 50 pigs, men take many more decisions than in enterprises with fewer than 50 pigs. Moreover, men still generally take the major decisions regardless of enterprise size. These include breed selection and securing sires (ibid.).

In short, the literature signals extensive variability in women’s recognition, resources, opportunities, and decision making as they pursue livestock initiatives.

3. Materials and Methods

Sampling in GENNOVATE was purposive and guided by maximum diversity procedures [40]. The sampling frame for community selection focused on four variables: high or low gender gaps and high or low economic dynamism. Gender gaps were assessed with reference to indicators such as levels of women’s leadership, physical mobility, education levels, access to and control over productive assets, and ability to market and benefit from sales of agricultural produce. Indicators for economic dynamism included levels of infrastructure development, integration of local livelihood strategies with markets, labor market opportunities, and resources available for innovations in agriculture. Our sample includes 73 GENNOVATE village-level case studies in 13 countries:

- 42 cases from Asia and Central Europe: Afghanistan (4), Bangladesh (6), India (15), Nepal (6), Pakistan (7), Uzbekistan (4)

- 25 cases from sub-Saharan Africa: Ethiopia (8), Malawi (2), Morocco (3), Nigeria (4), Tanzania (4), Zimbabwe (4)

- 6 cases from Latin America: Mexico (6)

In each village, interviews with key informants of both sexes were conducted to complete a community profile with background on local demographic, social, economic, agricultural, and political information. Data was generated from six sex-specific groups: (i) low-income women and men (aged 30 to 55), (ii) middle-income women and men (aged 25 to 55), and (iii) young women and men (aged 16 to 24). In two Mexico cases, there were no FGDs with young men. All data collection instruments featured semi-structured questions either conducted with individuals or in a group setting. Individual life-story interviews were held with two men and two women in each community to discuss agricultural innovations in the broader context of their life story. Semi-structured innovation pathway interviews were conducted with two women and two men locally known for trying new things in agriculture—to explore the processes behind and their experiences in engaging with such innovations.

Preferences for agricultural innovations were also explored during focus group discussions (FGDs) where members identified agricultural innovations which were introduced to or developed within their community over the past five-to-ten years. Innovations are broadly defined to include new cropping or livestock technologies or other novel agricultural practices or ways of learning or organizing. Having produced a list of recent local innovations, FGD members then ranked and discussed the two most important innovations for their own gender and the two for the opposite gender. Low-income FGDs also included a Ladder of Life exercise, which developed locally relevant well-being categories and explored gender dimensions of local poverty dynamics. Although not prompted, livestock sometimes featured in these testimonies.

All tools were applied by facilitators of the same gender as the respondent(s). An ethics script was read to respondents prior to commencing each activity and consent obtained to proceed. Petesch et al. (2018) [14] provide further discussion of methodology. All community names in this article are pseudonyms.

The narrative data were translated and systematically analyzed and coded with QSR NVivo software using codes derived from the study’s theoretical framework (e.g., agency, gender norms, enabling factors for innovation adoption) and emerging themes from data. We applied variable-oriented analysis to identify recurring themes, and contextual case-oriented analysis for the case-study findings. For the latter we here focus particularly on the community of Taral in Rajasthan, which we return to in relation to each domain in the findings section and for which we provide a brief background description below. We highlight Taral because this case presents an opportunity to illustrate and learn from possibilities for beneficial synergies across the four domains and from the easing of some gender disadvantages that accompanies these processes. Furthermore, Taral was chosen for its unique context enabling women to synergistically benefit from livestock innovations (including contract farming, a milk collective, as well as feed and livestock innovations). We refer to other cases as relevant.

The Village of Taral

Taral (population 12,300) benefits from many government and NGO interventions. Women involved in dairy farming sell milk to and receive technical information from a local Dairy Center. SABMiller, a global beer brewer active in four Indian States including Rajasthan, has introduced a malting barley cultivar (locally called Sample Barley) together with improved agronomic practices. SABMiller provides the barley seeds and inputs to farmers and buys the harvest back from them. The costs for the inputs are deducted after harvesting. SABMiller’s extension program is called Saanjhi Unnati, or Progress through Partnership (see [41,42]). All extension workers are men and participating farmers are usually men as well. However, in Taral some women have been recruited by SABMiller through the Dairy Center to grow the new barley variety as well.

Women in Taral have long been identified as livestock keepers at the household and community level. Young women take livestock as part of their bridewealth into marriage. In male-absent households—due to outmigration or when women are widowed—women manage farms and sharecrop. Men are considered ‘farmers’ and are closely identified with crops. Women are, however, strongly involved in agricultural work and describe ‘helping’ their husbands irrigate, sow, weed, harvest, etc. Over the past decade, women have increased their involvement in working with field crops and sometimes as hired labor. While the study was not designed to examine gender and caste interactions, we acknowledge that caste is a significant structural variable that may inhibit the expression and realization of women’s (and men’s) agency, as well as their ability to source various capitals [43].

4. Results

4.1. Overview of Top Two Innovations Related to Livestock across the Study Sites

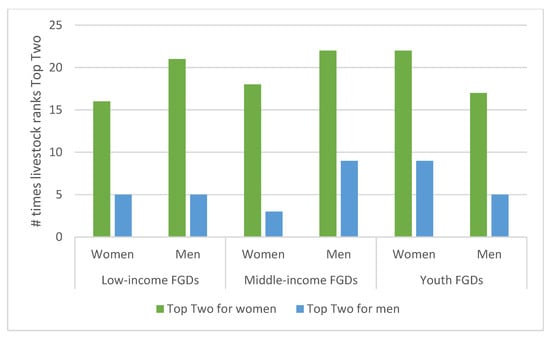

When asked about the two most important agricultural innovations—for the livelihood of women and men—which were introduced to or developed within their community over the past five-to-ten years, livestock emerges as one of the Top Two innovations for women or men, or both, in 36 of the 73 community case studies in our dataset. Regardless of socio-economic status or age-group, both women and men study participants mentioned livestock technologies as part of the Top Two far more often for women than for men (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency of livestock innovations ranked as a Top Two by gender (208 FGDs from 35 village cases in 11 countries).

The relative importance of the Top Two livestock innovations to women’s livelihoods varies by region and country. In Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, Rajasthan, Uzbekistan, and Morocco, Top Two livestock rankings (mentioned by women and men alike) are almost exclusively associated with women. In comparison with these countries, cases from sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) show men to be more likely than women to be associated with the top-ranked livestock innovations. A notable exception to these SSA patterns, however, is Ethiopia where livestock widely emerges as a top-ranked innovation for both women and men. The Mexico cases only rarely depict livestock as a Top Two for either gender. Respondents in Nigeria and Afghanistan did not present any Top Two rankings for livestock, though women in these countries discussed livestock as a means for moving out of poverty in the Ladder of Life exercise.

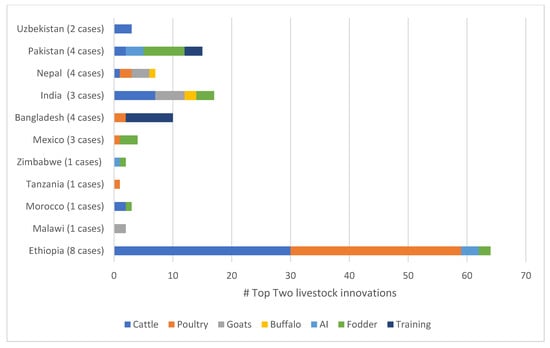

Figure 2 displays the Top Two innovations for women by country and category (livestock species, type of intervention—artificial insemination (AI) and fodder—and capacity development) and reveals livestock to be widely recognized as important for women’s livelihoods. The FGD testimonies indicate that improved dairy cattle are important for women in many cases from South Asian countries, Morocco, and across the six Ethiopia cases. Improved poultry breeds also appear often among the top rankings for women in Ethiopia, and improved goats emerge in cases from Nepal, India, and Malawi.

Figure 2.

Top Two livestock innovations for women by type of animal or related activity (192 FGDs from 32 village cases in 11 countries).

It is noteworthy that capacity development (mentioned in the interviews as ‘training’) in relation to livestock is an important innovation for women in Pakistan and especially Bangladesh. Another innovation which stands out relates to fodder, e.g., fodder choppers and improved fodder. It is important to notice that failure to mention other innovations that could potentially increase productivity (such as AI) in some of the case studies may well reflect lower incidences of such technologies in the communities under study rather than the degree to which women might value them.

We now discuss our results in more detail and in relation to the four domains of women’s self-determination. Each sub-section is organized into two parts: (i) cross-case patterns and (ii) the Rajasthan case of Taral.

4.2. Domain 1: Livestock and Recognition

In this section, we assess the ways in which empowerment and women’s recognition as livestock keepers are associated.

4.2.1. Cross-Case Findings

Men are strongly recognized as cattle farmers in cases from Ethiopia, Malawi, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. Cattle in these communities are widely described as a “bank for men.” Improved cattle/oxen allow men to obtain higher prices from livestock and meat sales and benefit from the animal’s improved load-bearing capacity and ability to plough more rapidly than local breeds, thus supporting typical male tasks in the field and in marketing. In some communities, they are used to pay bride price. Men do not use cattle to defray household expenses but rather for larger expenses, e.g., housing construction, farm inputs, cropland rentals, school fees, enterprise ventures, medical care, and court fines. As a man in Ethiopia explained:

“We men, whenever we want a large amount of money, say to build a house or rent land, we can sell cross-bred cattle for a high price. The demand for such cattle is higher in the market. For us selling improved cattle means opening a shop business. It is always something to depend on. If a farmer got into financial trouble and if he has such cattle, he will cope with the problem by selling them. Having such cattle is considered as having money in the bank.” (low-income men’s FGD, Wariso).

Although women in several case studies are not considered “owners” of cattle in terms of being able to decide whether to purchase or sell them, their role in caring for cattle is widely recognized. This role (which includes feeding) is probably why women listed improved fodder as an important innovation in many countries. Yet, the fact that cattle is mentioned in some countries as most important for women livelihoods raises the question whether cattle innovations: 1. support women’s livelihoods by easing their role as caretakers or 2. offer opportunities to expand women’s livelihoods beyond their role as carers. It is possible that local norms discourage a public association between women and cattle ownership, yet communities do recognize cattle’s transformative potential for women’s empowerment.

An exception to the male dominance of cattle opportunities in the African cases is Ethiopia, where dairy cattle feature strongly among the Top Two innovations for women as well as men. Women do not necessarily own these animals (in the sense of having full decision-making capacity over them) but traditionally have full responsibility for producing and selling dairy products and retain control over this income. Improved dairy cattle which produce a higher quantity and quality of milk are of great value to women. Improved cattle save women time and resources because they are considerably more productive and thus fewer animals (and less labor) are needed. “One cross-bred cow is more advantageous than ten indigenous cows in terms of yield and time management for women who have much more responsibility in the household” (middle-income men’s FGD, Akkela, Ethiopia). Unsurprisingly, Ethiopian women and men also ranked AI and improved fodder highly.

4.2.2. Taral Case Study

The women of Taral are innovating with new cattle breeds and dairying and are unquestioningly recognized as livestock farmers. Central to these achievements is their membership in a village-level Dairy Center, which has allowed existing community recognition of women as livestock keepers to become institutionalized and formalized. In addition to their spouses, many women indicate the Dairy Center to be an important source of information. The women testified that the Center not only collected milk from women’s homesteads but also provided an outlet for women to “go out and sell their milk”, enabling women to forge greater freedom “to go out of their homes” and to “help their husbands with farm work.” In such ways, the Dairy Center has contributed to relaxing the norms that discouraged women from being recognized as livestock farmers and that limited their physical mobility, social interactions, and information access.

The government RAS does not provide women with any support regarding improved livestock breeds or associated innovations. Yet, women’s increasing participation in the local economy and the Dairy Center have enabled women dairy farmers to become “visible” to other external partners, which we discuss below.

4.3. Domain 2: Livestock and Resources

In this section, we assess the pathways by which women access livestock and associated resources.

4.3.1. Cross-Case Findings

Many cases from South Asia and Ethiopia show that livestock innovations provide both productive and reproductive resources to women, with the recognition of women’s livestock roles being fundamental to their resource access and control. These resources are vital as women are otherwise often unable to access and benefit from local innovation processes.

The village of Chandni in Rajasthan presents a case of diverse types of women benefiting from improved goat breeds, including women with low incomes. Chandni’s women especially praised the Bhaul goat, which produces four-to-five kids per year, rather than the two provided by the local breed, and between two-to-four times more milk. They also mentioned another new goat breed they called Marwari that produces good quality milk and requires little forage. Respondents believe that goat milk is good quality, nutritious, and can combat health issues such as diabetes and dengue fever. It, therefore, has a strong market. According to a member of Chandni’s low-income men’s group, the new goat breed ranked as a Top Two for women because a goat is “small livestock, anyone can easily rear it with minimum feed. This is why goats are called ‘cows of the poor.”

Cases from Rajasthan and Pakistan also highlighted improved fodder as being a resource of particular significance to women. AI also ranked highly in cases from Pakistan. Again, in cases from Bangladesh as well as Pakistan, capacity development in livestock care and management emerges as a valued resource (contributing to human capital). Other significant innovations that provide valued resources for women include zero grazing pens, particularly in societies where women experience low mobility. In Ismashal, Pakistan, men remarked that zero grazing benefits local women because they can easily manage care within the homestead “like giving feed to them, milking them, cleaning the area where they are kept, and so forth” (low-income men’s FGD).

4.3.2. Taral Case Study

Women’s access to resources to support and expand their livestock activities is limited in Taral to mostly the Dairy Center and their kin and informal networks. Women do not own land; even when land is purchased with pooled family resources, it is often under the names of men. They cannot access formal credit (and thus rely on informal loans from family or local lenders). Women are generally not expected to attend agricultural training events. Furthermore, women report feeling too busy due to household chores and livestock care to attend meetings, and some women need male permission to leave their homes.

In Taral, valuable crop–livestock resource synergies have developed due to improved barley technologies and contract farming opportunities. The new cultivar is grown by men with sufficient land and provides men with an income through guaranteed sales to SABMiller (which pays slightly more for barley than the price set for wheat). It is worth mentioning that barley crop, as opposed to wheat, requires less water and fertilizer but lacks a ready market, which in this case SABMiller provides. Village women—of varied socio-economic and generational categories—who previously went to significant effort to source fodder for the cattle, now have high-quality barley straw and some barley grain close at hand. Improved fodder translates into enhanced milk production. In turn, women use their increased income from milk sales to build their herds. The efficacy of the fodder is further improved through the use of fodder cutters, which have been recently introduced. The increasing replacement of wheat by barley is key to women’s expanded livestock production. These crop–livestock synergies also benefit low-income households which do not plant barley but can purchase barley straw to provide good fodder to their animals because wheat straw is less suitable as livestock feed, nutritionally and in terms of palatability. Through their ever-more productive dairy businesses, women provide more milk to their household, thereby strengthening their family’s nutrition, and generate additional income through selling greater quantities of milk to the Dairy Center. Women are aware of these synergies. They explain, “The hybrid barley variety gives us more fodder. It is useful for our livestock, and it helps livestock produce more milk” (middle-income women’s FGD).

Table 1 presents the top-ranked innovations from Taral’s six FGDs. The ability to provide cattle with nutritious fodder emerges as particularly important in several FGDs because women (including those with low incomes) are innovating with Holstein, Jersey, and Friesian cattle which require high-quality fodder. Table 1 also shows that women across socio-economic and generational groups are accessing fodder choppers. Crop-based innovations including sprayers, groundnut digging machinery, and the new barley variety are also prominent, supporting the evidence that many village women are accessing resources that enable them to benefit from the innovation processes of their village.

Table 1.

Top Two innovations for women in Taral (6 FGDs).

4.4. Domain 3: Livestock and Access to Opportunities

In this section, we examine how low-income women and men use livestock as an opportunity to better their lives. We also consider how women obtain opportunities to improve their livelihood portfolios and the associated businesses of their households.

4.4.1. Cross-Case Findings

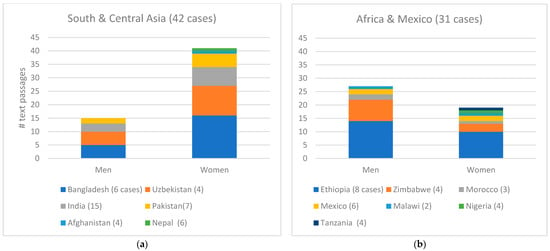

Half (73) the 146 low-income FGDs which conducted the Ladder of Life exercise (see Section 3) reported livestock opportunities to be one of the pathways by which local women and men have contributed to moving their households out of poverty. These narratives on livestock-related upward mobility contain 30% more text passages referencing women who employed livestock-related initiatives compared to men.

Figure 3 shows that it is cases from South Asia, Uzbekistan, and Ethiopia where FGDs most often refer to livestock activities when identifying strategies that local women have used to help move their households out of poverty. In cases from Ethiopia and Zimbabwe, men emerge as more likely than women to employ livestock opportunities, although women are often referenced in Ethiopia.

Figure 3.

Frequency of references to livestock as an opportunity to move their families out of poverty in Ladder of Life FGD dis-cussions. Source: 84 FGDs with low-income men and women from Asia and Uzbekistan (a); 62 FGDs with low-income men and women from Africa and Mexico (b).

4.4.2. Taral Case Study

Changing opportunities in Taral are providing greater space for women to maneuver and innovate with their livelihood activities. Improved breeds and other livestock innovations represent an important opportunity for women to increase their income, meet household consumption needs, and become recognized as providers. Expanded opportunities for barley producers are also, in turn, challenging the idea that only men are “farmers.” Extension workers with Saanjhi Unnatti (SABMiller brewery’s outreach program) invited women members of the Dairy Center to participate in their barley program as contract farmers, with one woman acting as a model farmer. She explained:

“Together with other women from my village, I attended meetings with a SABMiller representative. He told us about the benefits of growing barley. I decided to join Saanjhi Unatti and to try a new barley variety. The company members gave a demonstration on my farm about how to grow its barley seeds,” (Woman innovator, Taral).

Many testimonies suggest that the Dairy Center was the initial driver of women’s changing roles and opportunities in Taral. This was compounded by improved education for women in the community and better off-farm opportunities for men. “A decade ago women were not allowed to do farming activities. But now we can do everything what we want to do, like dairy, livestock, farming, and so forth,” reports a member of the women’s low-income FGD. The woman innovator cited above explained how respect for women’s new identities as crop farmers is shifting from within the household to the community. “I received more respect after I tried the new barley seed variety because the trials were successful. Every member of my family is now giving me more respect because my decision to grow the new variety of barley was right. Other people outside of my house also give me more respect now” (Woman innovator, Taral). Her experiences speak directly to important synergies across the four domains. However, we also found that women’s involvement in contract farming led to increased work burdens: “my children are affected. I cannot concentrate on their health and food because I am doing work on farm the whole day after adopting Saanjhi Unatti’s barley seeds”.

4.5. Domain 4: Livestock and Women’s Decision Making

In our analytic framework, decision making is the key cross-cutting domain to enabling women’s recognition and access to resources and opportunities as livestock farmers.

4.5.1. Cross-Case Findings

Across diverse cultural and agroecological contexts, some women testify to taking important decisions over their livestock livelihoods. Male outmigration in cases from Nepal is strengthening women’s ability to manage livestock. Young women in Ranagar, for instance, reported buffalo raising as a Top Two innovation for women. These are zero grazed, and women are able to decide on veterinary care and AI. The young women expressed strong agency and attributed this in part to their mothers, who participate in agricultural training courses and encourage their daughters to do likewise.

In Ethiopia, it has long been normative in many of the study villages for women to manage income from dairy products and poultry, though in some contexts women do not experience full autonomy. As a member from Nebele, Ethiopia’s middle-income FGD, explains:

For women dairy cows are important because the husband will never ask about the income from butter, cottage cheese or milk. In addition, he would not be concerned if the chicken is sold by the woman herself. So, for us dairy products and chickens are the things that help us to get a bit of extra income.

Another in this same group confirmed the women’s control over the produce, “Taking care of improved local cattle means additional work for women. But the milk will be useful for the children and the man. We also collect and process milk and sell part of it.”

In many cases, it is normative for men rather than women to engage in cattle markets, but our evidence finds women negotiating this norm. In Gobado in Ethiopia, for instance, women sell cattle provided they have their husband’s consent, and study participants testify that men also cannot sell cattle without their wife’s consent. An important reason for this outlier case appears to be active engagement by village members in a series of awareness-raising and learning sessions that were part of a Community Conversations program held locally several years ago. The program explored and raised questions about gender roles and responsibilities and the gendered taboos and institutions of the community (see [44] for further discussion). Traces of Community Conversations are evident in local norms that continue to provide many village women with greater freedom to pursue goals. Other study communities in Ethiopia also show signs of change, although not to the extent of Gobado. In Nebele, for instance, governmental programs focused on women’s rights have supported women’s growing participation in markets. This in turn is creating feedback loops whereby women gain more knowledge and new economic relationships. Women reported that “When we went out to work, we began to be exposed to and learned things. We have started selling and buying. Things are slowly changing” (middle-income women’s FGD, Nebele).

Interactions between women’s growing decision-making capacity and the other domains shaping self-determination are especially evident in the case of Madpur, Bangladesh. Low-income women of Madpur reported launching livestock portfolios by raising chickens and ducks and depositing money from selling eggs and birds in the local saving group. Once savings are adequate, they purchase cows and goats, and in due course “sell milk and cows to deposit more money.” Women’s opportunities for accumulating livestock resources are complemented by men’s initiatives, which include investing in and selling large livestock to lease land for cultivation. The data do not allow us to demonstrate causality between men’s and women’s complementary livestock and crop initiatives, women’s empowerment, and greater gender equality. In this case, however, it is significant that men’s testimonies indicate gender relations to be highly cooperative and that they are facilitating women’s decision-making power. Some men provide women with gifts of goats and cows to “encourage and inspire her productive work” (low-income men’s FGD, Madpur, Bangladesh). The catalytic interactions between women’s decision making, recognition as producers, and capacities to participate in local agricultural innovation opportunities clearly echo in this man’s testimony:

In our village, most women support their husbands more often than in the past to move ahead. Women give good advice regarding the daily activities of their husbands. A wife also looks after their crop cultivation herself in absence of her husband and she takes care of all livestock” (ibid).

4.5.2. Taral Case Study

The testimony of a 21-year-old farmer and mother of two from Taral presents another insightful example of the strong and dynamic interactions between recognition of women as agricultural producers and their decision-making power. This young woman is widely recognized in the community as an innovator with livestock and barley, and reports:

Respect for me has increased now. And my family members now give me more importance because all my family members know that I can decide everything on my own. And my family members believe me because they have seen the results of my trial of Sanjhi Unnatti’s barley seeds (innovator interview, Taral).

She is also well educated and reports that her livelihood initiatives have enabled her to continue with her studies. Indeed, toward the end of her interview, she shared, “People look at me like an idol for girls and women in my village.”

Taral’s middle-income women similarly emphasize they are experiencing greater power to take decisions: “Women can decide whether they want cows, buffaloes, or goats.” In the low-income group, women indicate that women can now “get education if they want,” and the local men “respect women. Men give importance to women’s suggestions.” Finally, some young women in their FGD highlighted the importance of education as a further necessary component to strengthening their voice. Education means “now our parents talk to us before taking any major decision about us.”

While different norms are relaxing for Taral’s women, others persist, and expectations appear to be especially restrictive pertaining to women’s entrepreneurship. Women in Taral, for instance, are permitted to visit the local market as customers, but no woman can trade there or in more distant markets. One woman, recognized as a successful innovator, explained:

Both my husband and I can sell milk. But my husband can sell milk outside the village while I can only sell milk within the village to the Dairy Center. Livestock are sold by my husband because livestock are a big asset. Also, my husband knows more than me about selling livestock.

Nevertheless, this respondent explained that she had a higher degree of decision-making power than many women because, at 40 years old, she was perceived to be an elder. Women’s statuses as wives and mothers mediate their sense of agency in significant ways. Married women gradually gain bargaining power as their children become older and they become mothers-in-law.

The broader picture is, though, that women’s and men’s incomes are often pooled and used to purchase major assets under the husband’s name and control. Many testimonies indicate that this continues to be the norm in Taral even as women’s productive and decision-making roles have grown. “I started vegetable growing in 2005 to increase my family income. With that income and the profits from the dairy products my wife sold, I bought a tractor,” observes a man from Taral during his life story interview. Although most members of the Taral young women’s FGD expressed healthy levels of agency, some testified to having constrained choices: “Young women do not take new animals for raising. And young women cannot take the decision to sell.” Many in Taral’s other two FGDs with women likewise need their husband’s permission to innovate or to take other important decisions.

While normative change appears to unfold unevenly, diverse women in Taral nevertheless testify to gaining recognition as livestock keepers, accessing resources and opportunities, and taking decisions that equip them to better manage their reproductive and productive responsibilities. All the women in the youth focus group perceived the great majority of the local women to move freely in their village, and “In our community a young woman can walk comfortably alone to the market.” By comparison, in the other Rajasthan case of Chandni, women’s mobility and social interactions beyond their homesteads remains constrained, but in recent years they have been able to purchase livestock after consulting with spouses and in-laws. They explain this is “…because now people are educated and give some rights to women so that women can also help their husband in every situation” (low-income women’s FGD, Chandni). In Taral, Chandni, and many other cases, local norms encourage only men to assert claims on major resources, leaving women with scarce means to grow their enterprises.

5. Discussion

Livestock innovations can constitute important avenues for women’s empowerment. In 36 of 73 cases, they emerged as one of the two most significant agricultural innovations, particularly for women’s livelihoods. However, biophysical technologies alone do not open these avenues. Livestock can lever change towards empowerment when all the components of self-determination, represented in the conceptual framework applied here, are in place. Furthermore, livestock-related innovations contribute to women’s empowerment when they act synergistically (e.g., improved fodder, fodder choppers, improved livestock) to open spaces for women to negotiate and alter gender biases. The findings show that women appear to value access to technologies such as choppers or forage varieties—when they are available—as much as the improved breeds themselves. This is not surprising because an improved technological infrastructure (or innovation package) is generally required to support these breeds to maximize their productivity.

Our analysis indicates that investments in livestock hold potential for shifting gender norms in ways that empower women for sustained change over time. Addressing gender norms is key to more lasting and sustainable change because it addresses the root cause of gender discrimination [22,45], as demonstrated by the Gobado, Ethioipia, experience with a community-based educational program on norms. Our findings show that innovation processes are both impacted by, and impact on, women’s agency and can help to shift local norms that govern gender roles and gendered benefits, but also that experiences of innovation can be very different across sites. We now discuss each domain separately before examining how they come together.

Recognition: We find that in many communities, livestock emerges as a key innovation perceived by study participants to be important for women. In cases from Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, Rajasthan in India, Uzbekistan, Morocco, and Ethiopia, women appear to be recognized at a community level as livestock keepers. These cases further show that women are recognized as controlling and having strong interests in cattle, and, depending on the context, goats, buffalo, and poultry, too. The weaker identification of women with livestock in cases from Tanzania, Malawi, and Zimbabwe is striking, particularly given that livestock are widely present in these environments. Men are strongly identified with cattle across these cases and exclusively identified with the top-ranked livestock innovations in the Zimbabwe cases.

This evidence is in line with gender literature which shows the frequent association of only men to farming and women to ‘helpers on the farm’ [22]. The related invisibility of women as farmers and consequent lack of access to assets and opportunities has been shown [22,29] (see also Analytical Framework). Our evidence shows, also, that the lack of recognition can vary at various levels: community members in many study villages recognized women as livestock keepers, but this was not necessarily the case for external stakeholders. In the Rajasthan cases, women do not receive any assistance from the RAS with respect to livestock, for instance, on how to source and care for improved breeds. There can thus be a significant contradiction between community perceptions and those of external stakeholders. In several cases from Bangladesh and Pakistan, women rank training opportunities highly, suggesting stronger institutional recognition in those locations of women as livestock keepers. Strengthening community-level recognition through the provision of institutional support is critical since this directly strengthens their ability to access, accumulate, and benefit from livestock. This is strongly demonstrated by the experience of women in Taral in Rajasthan, whereby The Dairy Center enabled an external private sector company, SABMiller, to identify—and work with—women as farmers. Some of Taral’s women barley producers then invested their profits in enlarging and innovating with their livestock businesses.

Resources: In and of themselves, livestock constitute an important resource and a means for responding to emergencies, or, as mentioned by study participants across the study sites, for improving livelihoods and moving up the Ladder of Life. We show that, in many countries, women and men highlight the importance of women’s livestock activities in contributing to the escapes from poverty of local households. In some contexts, the data signal linkages between socio-economic position and species/breed choice. In Chandni, for example, low-income women primarily, though not exclusively, select goats, including improved breeds, while middle-income women select improved goats, cattle, and buffalo.

It is interesting to notice, also, the asset accumulation opportunities offered to women by livestock and, particularly, the potential for poor women of keeping various species at the same time, including more lucrative ones (such as chickens, ducks, goats, and then cows) that usually belong to the better-off or men. Growing evidence refers to the ‘livestock ladder’ when showing the asset accumulation potential that livestock offer to women and their economic empowerment [46,47] (see also under ‘opportunities’ below).

The prominence of improved fodder and fodder choppers among the innovations across continents implies that women everywhere value fodder-based interventions along with other livestock-related technologies. Some of these technologies have also reduced the workloads of women; the electric fodder-cutting machine was ranked second by poor women in Talar as it reduced the time and energy required for cutting fodder. The importance for women of fodder-related innovations could be explained by the fact that improved livestock breeds necessitate improved forage management (as well as improved animal health practices) for productivity to be sustained. Improved animal feeding is often a challenge for women for two reasons: they do not own or control land to grow the forage [48]; they are tasked with the labor-intensive collection and chopping of fodder.

Opportunities: Through their identity as livestock keepers, women leverage opportunities that can shift their lives onto a different trajectory. The Taral example illuminates how gender norms contribute to structuring women’s opportunities. Through providing a reliable and accessible market and information source, the Dairy Center helped women to press for the relaxation of diverse norms and gain visibility in the local economy. Compared to their lives a decade ago, the women of Taral observe greater freedom for many women to decide to engage in paid work, become educated, and move more freely around the community. This in turn enabled external actors to target some of the village women for barley production and with education opportunities—usually provided exclusively to men. The value of leveraging existing openings to change inequitable gender norms towards less strict normative frameworks has been discussed by Galiè and Kantor [2,37]. Our findings show how livestock can provide opportunities for such processes of change in gender norms. Evidence from a WELI study in Tanzania shows that none of the respondent women achieved adequacy in access to livestock-related opportunities [1].

Our findings speak to the opportunities that livestock offer for women to build their own assets, for example, from investing in poultry to obtaining goats and then cattle. In the case of small species, which women can traditionally own in most contexts, improved breeds can provide incremental earnings that women can reinvest (e.g., in more stock) to build their asset base. In the case of larger species (e.g., cattle in Taral) women’s control and ability to build their asset base may be dependent on the availability of improved forage varieties, choppers, and market opportunities. Much evidence, however, shows that increasing the lucrativeness of livestock enterprises can result in male capture of the benefits [28,49]. Further work is needed, nevertheless, to understand the dynamics that enable women to accumulate and maintain control of numerous livestock as they expand their enterprises.

Finally, control over livestock and recognition as livestock farmers seem to constitute potential building blocks of women’s empowerment that need an opportunity—e.g., male migration and off-farm employment—to translate into actual empowerment by increasing women’s decision making.

Decision making: Data from the WELI study in Tanzania show that the respondent women achieved adequacy in decision making only in relation to nutrition. Their score was inadequate across all other domains of decision making [1]. Our data on decision making add nuances to this evidence by showing that decision making can be interpreted at two levels: meta-level changes, which potentially open opportunity spaces for women to strengthen their decision-making power, and community-level changes that also enhance women’s agentic capacities. Meta-level forces include changes underway that are exogenous to the community, such as universal education, market forces, technological change, and labor migration—all of which are heavily gendered. The study was not designed to assess these processes, but their importance is evident in many testimonies. Women’s increasing access to education and awareness of their rights appear as important for women to aspire to and pursue livelihood goals. Members of Taral’s low-income men state that “thinking has changed due to education,” and it is now acceptable for “women to work outside their home in local jobs.” In Nepal, it appears that male outmigration contributes directly to women experiencing more decision-making power [50]. In conservative communities in Ethiopia, women are also experiencing some positive changes and identify their livestock activities as important to this. Many women across the cases expressed their agency in relation to being able to influence and cooperate with their spouse and spoke of gaining decision-making capacity as their children grew older and married. Where possibilities expand for women to access opportunities and take decisions, women may continue to perceive their agency in highly normative ways; however, these structural dimensions can be important drivers of agency in both the productive and reproductive spheres of women’s lives as these spheres are so intertwined in farming households.

Expanding spaces for synergies: The experiences of Taral illuminate the potential for local innovation processes marked by strong livestock–crop synergies that present desirable and remunerative livelihood opportunities for women and men alike. The Dairy Center emerges as key to unlocking these synergies, by encouraging women to negotiate and, over time, begin to shift the norms that constrained their recognition as livestock keepers. The Center also connected Taral’s women to the barley innovation and cropping opportunities. In addition to improved fodder for their cattle, some women were able to move into a significantly new role—as own-account farmers engaged in crop production. Management of field crops is a new domain for women. The improved fodder from barley straw (the grain is sold to SABMiller) is leading to greater milk production and sales. Improved sales in turn (together with the reliability of improved fodder and associated interventions such as fodder choppers) are contributing to women’s willingness to purchase high-yielding and high-fat-content milk cows, such as Jersey and Friesian, and Murrah buffalo. Another effect is undoubtedly improved nutrition at the household level, both for producer households and those where milk is purchased. The data also show the strong interconnection among empowerment domains that are all needed to progress towards empowerment, given their complementarity [51]. On a methodological note, such strong complementarity meant that in our analysis it was difficult to assign some findings to a given domain because they overlapped across more domains (such as, for example, livestock offering opportunities for visibility (does it contribute to ‘recognition’ or ‘opportunities’?) which in turn entailed increased decision making (therefore belonging under ‘recognition’, ‘opportunities’, or ‘decision making’).

The GENNOVATE study did not focus on livestock innovations, yet the findings offer a unique bottom-up view of gender differences in livestock as propellers for innovation, escapes from poverty, and for empowering women in particular. Nevertheless, a future study with a specific focus on this would be important to further explore our findings. On the theoretical front, it would be valuable for further work to clarify boundaries and interactions between resources and opportunities in the Sachs and Santarius [21] (2007) framework. Either cattle or training, for instance, could arguably be classified as a resource or an opportunity.

Another challenge in this study was that the data sometimes had gaps because livestock was not a focus. In some FGDs, we could not identify the source of the livestock innovation or the type of breed or training. More generally, it was not clear why livestock was highly ranked or often mentioned in some cases but not others. It is also possible that, because men access more diverse resources and opportunities than women, the evidence generated did not meaningfully capture men’s livestock initiatives. A future study could also probe more deeply into the gender relations surrounding livestock as a pathway for women’s self-determination. As men also benefitted from the barley contracting opportunities in Taral, for instance, this appears to provide more space for women’s innovation and decision making along with increased access to fodder in the community more generally. The increased time burden associated with the preferred innovations could indicate a possible decrease in women’s empowerment (see, e.g., [1,52]). Unfortunately, our study did not delve in depth into livestock innovations and women’s time in relation to empowerment, an issue that we recommend for further exploration.

6. Conclusions

Our paper is based around an analytic framework that attempts to bring together the components necessary for women to realize self-determination. Yet, in no single case study do all the components of self-determination—recognition as farmers, access to resources, access to opportunities, and effective decision-making power—appear to be equally in place. The findings demonstrate that recognition of women as livestock keepers by meta-level institutional actors as well as at the community level is pivotal. To ensure balanced interventions that facilitate gender-transformative change, we recommend that development partners work to design interventions that strengthen women livestock keepers in all domains. We also point out the time costs incurred by women benefitting from such interventions and, to a lesser extent, time-saving technologies (e.g., fodder cutters). Offsetting these time investments should be a key focus of future interventions.

In many cases, much could be done by capitalizing on existing community-level recognition of women as livestock keepers. Working with the RAS to institutionalize this recognition and to target women as well as men with livestock innovations, including improved breeds and associated technologies, would go a long way towards strengthening women’s livelihood portfolios and contribute towards their self-determination. As the institutional dynamics expressed in the four domains vary greatly on the ground, contextualized research across the framework holds potential for advancing interventions that account more effectively for local realities and provide livestock-related innovations that act synergistically to address gender disadvantages and expand possibilities for women to empower themselves. In this way, our paper shows how the combination of institutional innovations (the domains of self-determination identified in our framework and approaches that address gender norms) and biophysical innovations (e.g., improved breeds, varieties, machinery), rather than the latter alone, is fundamental for sustained change towards women’s empowerment and gender equity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.G., D.N., P.P. and L.B.; Methodology: D.N., P.P. and L.B.; Formal analysis and investigation: A.G., D.N., P.P., L.B. and C.R.F.; Writing—original draft preparation: A.G., D.N., P.P. and L.B.; Writing—review and editing: A.G., D.N., P.P., L.B. and C.R.F.; Funding acquisition: L.B. and A.G.; Supervision: A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the CGIAR Research Program (CRP) on Livestock, CRP on Wheat, CRP on Maize, CRP on Dryland Cereals, and CRP on Dryland Systems (including all the donors and organizations which globally support the CGIAR system) (http://www.cgiar.org/about-us/our-funders/ accessed on 16 March 2022), as well as by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, grant number OPP1134630. Development of the original research design and data collection were supported by the CGIAR Gender and Agricultural Research Network, the World Bank, the governments of Mexico and Germany, and the CGIAR Research Programs on Wheat and Maize.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

The research involved semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions with men and women community members and followed the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Regulated Research Module, including informed consent procedures. To ensure appropriate ethical procedures were followed, before each data collection activity, the facilitators read aloud slowly and discussed a prepared statement. This explained the study purpose, assured confidentiality, and alerted the study participants that they had the right to not answer questions and were free to end their participation in the study at any time.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We warmly thank the women and men farmers and livestock keepers who participated in this research and generously shared their time and views, as well as all the members of the local collection teams and the data coding team. The views expressed in the article are those of the authors and not of any organization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Galiè, A.; Teufel, N.; Korir, L.; Baltenweck, I.; Girard, A.W.; Dominguez-Salas, P.; Yount, K.M. The Women’s Empowerment in Livestock Index. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 142, 799–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galiè, A.; Kantor, P. From Gender Analysis to Transforming Gender Norms: Using Empowerment Pathways to Enahance Gender Equity and Food Security in Tanzania. In Transforming Gender and Food Security in the Global South; Njuki, J., Parkins, J., Kaler, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 189–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjanson, P.; Waters-Bayer, A.; Johnson, N. Livestock and Women’s Livelihoods: A Review of the Recent Evidence; ILRI Discussion Paper 20; ILRI: Nairobi, Kenya, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Njuki, J.; Sanginga, P.C. Women, Livestock Ownership, and Markets: Bridging the Gender Gap in Eastern and Southern Africa; Earthscan; International Development Research Center & ILRI: Addis Abbaba, Ethiopia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Enahoro, D.; Lannerstad, M.; Pfeifer, C.; Dominguez-Salas, P. Contributions of livestock-derived foods to nutrient supply under changing demand in low- and middle-income countries. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badstue, L.; Petesch, P.; Farnworth, C.; Roeven, L.; Hailemariam, M. Women Farmers and Agricultural Innovation: Marital Status and Normative Expectations in Rural Ethiopia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Livestock Data for Decisions (LD4D). Women Livestock Keepers: Fact Check9; University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 2020; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1842/37437 (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Price, M.; Galie, A.; Marshall, J.; Agu, N. Elucidating linkages between women’s empowerment in livestock and nutrition: A qualitative study. Dev. Pract. 2018, 28, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiè, A.; Mulema, A.; Benard, M.A.M.; Onzere, S.N.; Colverson, K.E. Exploring gender perceptions of resource ownership and their implications for food security among rural livestock owners in Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Nicaragua. Agric. Food Secur. 2015, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Umaru Baba, S.; Van der Horst, D. Intrahousehold relations and environmental entitlements of land and livestock for women in rural Kano, Northern Nigeria. Environments 2018, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carpenter, C. Women and livestock, fodder, and uncultivated land in Pakistan: A summary of role responsibilities. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1991, 4, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavenner, K.; Crane, T.A. Gender power in Kenyan dairy: Cows, commodities, and commercialization. Agric. Hum. Values 2018, 35, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransom, E.; Bain, C.; Halimatusa’Diyah, I. Livestock-livelihood linkages in Uganda: The benefits for women and rural households? J. Rural. Soc. Sci. 2017, 32, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Badstue, L.; Petesch, P.; Feldman, S.; Camfield, L.; Prain, G. Qualitative, comparative, and collaborative research at large scale: The GENNOVATE field methodology. J. Gend. Agric. Food Secur. 2018, 3, 28–53. [Google Scholar]

- Eger, C.; Miller, G.; Scarles, C. Gender and capacity building: A multi-layered study of empowerment. World Dev. 2018, 106, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammage, S.; Kabeer, N.; Rodgers, Y.V.D.M. Voice and Agency: Where Are We Now? Fem. Econ. 2015, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, S.; Rambaree, K.; Jojo, B. Collective empowerment: A comparative study of community work in Mumbai and Stockholm. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2014, 24, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sen, A.K. Development as Freedom; Knopf Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Peterman, A. The women’s empowerment in agriculture index. World Dev. 2013, 52, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, N.; Balagamwala, M.; Pinkstaff, C.; Theis, S.; Meinsen-Dick, R.; Agnes, Q. How do agricultural development projects empower women? Linking strategies with expected outcomes. J. Gend. Agric. Food Secur. (Agri-Gend.) 2018, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, W.; Santarius, T. Fair Future: Resource Conflicts, Security, and Global Justice; Zed Books: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Galiè, A. The Empowerment of Women Farmers in the Context of Participatory Plant Breeding in Syria: Towards Equitable Development for Food Security. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2013. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/272924 (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Marshall, K.; de Haan, N.; Galiè, A. Integrating gender considerations into livestock genetic improvement programs in low to middle income countries. In Proceedings of the 23rd Conference of the Association for the Advancement of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Armidale, NSW, Australia, 27 October–1 November 2019; pp. 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Galiè, A.; Jiggins, J.; Struik, P. Women’s identity as farmers: A case study from ten households in Syria. NJAS —Wagening J. Life Sci. 2012, 64–65, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dixon, R.B. Women in Agriculture: Counting the Labor Force in Developing Countries. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1982, 8, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, I.; Lahiri-Dutt, K.; Lockie, S.; Pritchard, B. The feminization of agriculture or the feminization of agrarian distress? Tracking the trajectory of women in agriculture in India. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2017, 23, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.; Seyoum, T.; Caldwell, L. A Calf, a House, a Business of One’s Own: Microcredit, Asset Accumulation, and Economic Empowerment in GLCRSP Projects in Ethiopia and Ghana; Global Livestock CRSP: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Farnworth, C.; Kantor, P.; Kruijssen, F.; Longley, C.; Colverson, K.E. Gender integration in livestock and fisheries value chains: Emerging good practices from analysis to action. Int. J. Agric. Resour. Gov. Ecol. 2015, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora Benard, M.A.; Mena Urbina, M.A.; Corrales, R. The silent cattle breeders in central Nicaragua. In A Different Kettle of Fish? Gender Integration in Livestock and Fish Research; LM Publishers: Edam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 85–91. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/78649/kettle_ch13.pdf?sequence=2 (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Flora, C.; Flora, J. Rural Communities: Legacy and Change, 3rd ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mulema, A.A.; Farnworth, C.R.; Colverson, K.E. Gender-based constraints and opportunities to women’s participation in the small ruminant value chain in Ethiopia: A community capitals analysis. Community Dev. 2016, 48, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B. “Bargaining” and Gender Relations: Within and Beyond the Household. Fem. Econ. 1997, 3, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mwaseba, D.J.; Kaarhus, R. How do intra-household gender relations affect child nutrition? Findings from two rural districts in Tanzania. In Forum for Development Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; Volume 42, pp. 289–309. [Google Scholar]

- Randolph, T.F.; Schelling, E.; Grace, D.; Nicholson, C.F.; Leroy, J.L.; Cole, D.; Demment, M.W.; Omore, A.; Zinsstag, J.; Ruel, M. Invited Review: Role of livestock in human nutrition and health for poverty reduction in developing countries1,2,3. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 2788–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fafchamps, M.; Udry, C.; Czukas, K. Drought and saving in West Africa: Are livestock a buffer stock? J. Dev. Econ. 1998, 55, 273–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ravichandran, T.; Farnworth, C.R.; Galiè, A. Women-only and mixed-gender dairy cooperatives in Bihar and Telangana, India: Is there a difference for women’s empowerment? J. Gend. Agric. Food Secur. 2021, 6, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiè, A.; Farnworth, C. Power through: A new concept in the empowerment discourse. Glob. Food Secur. 2019, 21, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwambi, M.; Bijman, J.; Galie, A. The effect of membership in producer organizations on women’s empowerment: Evidence from Kenya. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2021, 87, 102492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninh, N.T.H.; Lebailly, P.; Dung, N.M. Labor division in pig farming households: An analysis of gender and economic perspectives in the Red River Delta, Vietnam. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2019, 9, 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- SABMiller India. Sustainability in Action SABMiller India: Sustainable Development Summary Report 2013. SABMiller India. Available online: https://www.ab-inbev.com/content/dam/universaltemplate/ab-inbev/investors/sabmiller/reports/local-sustainable-development-reports/sab-miller-india-sustainable-development-report-india-2013.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Bowe, C.; van der Horst, D.; Meghwanshi, C.; Assessing the Externalities of SABMiller’s Barley Extension Program in Rajasthan. Working Paper. 2013. Available online: https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/system/files/documents/SABMiller_Case_Study_Nov_2013.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Krishna, V.V.; Aravalath, L.M.; Vikraman, S. Does caste determine farmer access to quality information? PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mulema, A.; Lemma, M.; Kinati, W. Going to Scale with Community Conversations in the Highlands of Ethiopia; International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI): Addis Abbaba, Ethiopia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McDougall, C.; Badstue, L.; Mulema, A.; Fischer, G.; Najar, D.; Pyburn, R.; Elias, M.; Joshi, D.; Vos, A. Toward structural change: Gender Transformative Approaches. In Advancing Gender Equality through Agricultural and Environmental Research: Past, Present and Future; Chapter 10; Pyburn, R., van Eerdewijk, A., Eds.; IFPRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 365–402. [Google Scholar]

- Ramasawmy, M.; Galiè, A.; Dessie, T. Poultry in Ethiopia. In State of the Knowledge for Gender in Breeding: Case Studies for Practitioners; Grando, S., Tufan, H., Meola, C., Eds.; CGIAR: Montpellier, France, 2018; Available online: www.rtb.cgiar.org/gender-breeding-initiative (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Wong, J.; de Bruyn, J.; Bagnol, B.; Grieve, H.; Li, M.; Pym, R.; Alders, R.G. Small-scale poultry and food security in resource-poor settings: A review. Glob. Food Secur. 2017, 15, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njuguna-Mungai, E.; Omondi, I.; Galiè, A.; Jumba, H.; Derseh, M.; Paul, B.K.; Zenebe, M.; Juma, A.; Duncan, A. Gender dynamics around introduction of improved forages in Kenya and Ethiopia. Agron. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, V. The World has Changed; these Days, Women Are the Ones who Are Keeping Their Families. Gender Norms, Women’s Economic Empowerment and Male Capture in the Rural Tanzanian Poultry Value-Chain. Master’s Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2021. Available online: 1-108-sammanfogad.pdf (diva-portal.org) (accessed on 12 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Doss, C.R.; Qaisrani, A.; Kosec, K.; Slavchevska, V.; Galiè, A.; Kawarazuka, N. From the “Feminization of Agriculture” to Gender Equality. In Advancing Gender Equality through Agricultural and Environmental Research: Past, Present and Future; Chapter 8; Pyburn, R., van Eerdewijk, A., Eds.; IFPRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 297–328. [Google Scholar]