1. Introduction

International aid towards the attainment of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has dramatically shrunk in the past 5 years, with some of the world’s largest economies retreating from a period of what had been a steady increase in international aid [

1]. The UNESCO Global Geoparks were developed to support countries’ efforts to strengthen sustainable development.

The identification of the Colca Canyon in southern Peru in 1981 as the deepest canyon in the world (Guinness Book 1994), which was of great value to the environment and local culture, led to the establishment in 2019 of the Colca y Volcanes de Andagua UNESCO Global Geopark in Peru (Geopark Colca). The Geopark Colca has the potential to impact the achievement of sustainable development goals in Peru and on the Peruvian ecotourism market in a significant way.

Decreasing international aid most recently, largely as a result of economic uncertainty following the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 and its pernicious variants, magnified the importance of ecotourism in driving the delivery of SDGs in Latin America generally and Peru in particular.

Thus, every effort should be made to open the Geopark Colca as quickly as it is safe to do so. An awareness of the risks posed by COVID-19 and mitigation strategies for these risks should be at the heart of policy decisions.

This paper identifies the key risks of COVID-19 to the Geopark Colca and will contend that current modelling data indicates that the park and associated hotels and transportation links could be safely reopened if vaccination programmes are improved in Peru.

1.1. The Vision of UNESCO Global Geoparks

UNESCO Global Geoparks are single, unified geographical areas where sites and landscapes of international geological significance are managed with a holistic concept of protection, education, and sustainable development. A UNESCO Global Geopark celebrates its geological heritage, in connection with all other aspects of the area’s natural and cultural heritage, to enhance the awareness and understanding of key issues facing society, such as the reaction to climate change, using our earth’s resources sustainably, and reducing the impact of natural disasters.

For tourists interested in geodiversity, the existence of a network of geoparks plays an important role. UNESCO’s collaboration with geoparks began in 2001. In 2004, 17 European and 8 Chinese geoparks came together at UNESCO headquarters in Paris to form the Global Geoparks Network (GGN), where national geological heritage initiatives can contribute to and benefit from their membership to a global network of exchange and cooperation. At present, there are 169 UNESCO Global Geoparks in 44 countries and 5 regional networks including APGN (Asia and Pacific Geoparks Network), AUGGN (African UNESCO Global Geoparks Network), CGN (Canadian Geoparks Network), EGN (European Geoparks Network), and GeoLAC (Latino American and Caribbean Geoparks Network).

UNESCO Global Geoparks are established through a bottom-up process involving landowners, community groups, tourism providers, indigenous people, and local organisations, etc. This requires a firm commitment from the local communities with long-term political and public support. Additionally, it is necessary to prepare a comprehensive plan of development that will meet all the communities’ goals while showcasing and protecting the area’s geological heritage (

Table 1).

UNESCO Global Geoparks give local communities a sense of pride in their region and strengthen their identification with the area. They raise awareness of the importance of the area’s geological heritage in the past and current society. The creation of innovative local enterprises, jobs, and high-quality training courses is stimulated, and new sources of revenue are generated through geotourism while the geodiversity of the area is protected.

UNESCO Global Geoparks give local communities the opportunity to develop cohesive partnerships and empower them with the common goal of promoting the area’s significant geological processes, features, cultural themes linked to geology, or outstanding geological heritage.

The development of areas based on tourism is limited to those with qualities that attract visitors. One such quality is broadly understood as geodiversity, which includes: geology, volcanology, mineralogy, geomorphology, and heritage stone resources [

3]. In the high mountains, the glacier areas are exceptionally attractive, but also with clear postglacial forms [

4]. The geothermal potential [

5] of the area further enhances its attractiveness.

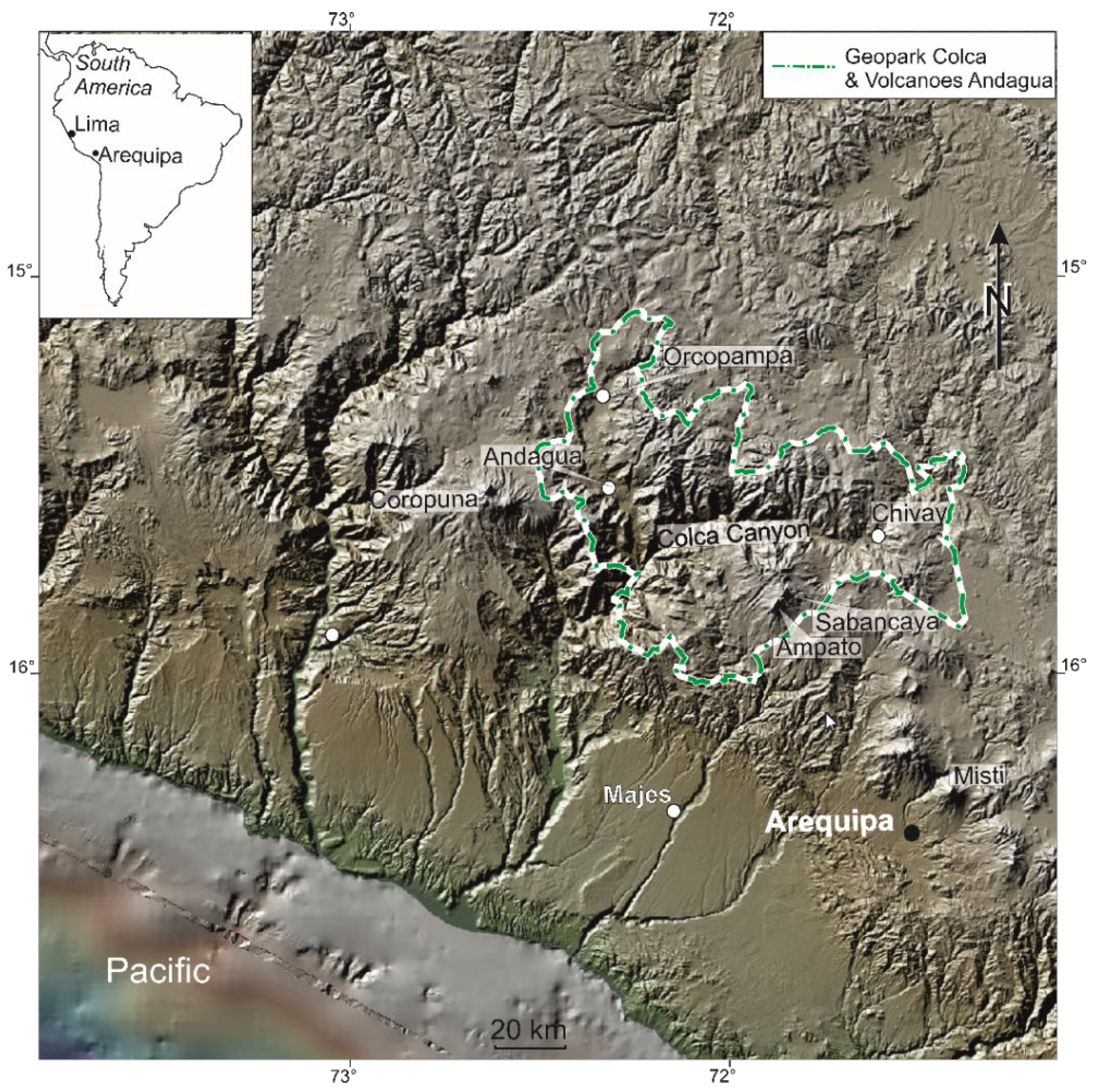

The Geopark Colca y Volcanes de Andagua (

Figure 1) has a variety of geo-attraction resources [

6,

7].

1.2. The Geopark Colca y Volcanes de Andagua (Geopark Colca)

Scientific work on the evaluation of the geoheritage in Peru that started back in 2006 in the Colca area was met with understanding and support from the regional and local authorities (

Table 2). From the beginning, the involvement and support of the political authorities (provincial Mayors of Caylloma and Castilla, and the Regional Governor of Arequipa, among other authorities) was very important. As time has shown, the political changes resulting from the term of office of the authorities have either accelerated or delayed the progress of works on the geotouristic valorisation of the area. The integration of geological information (volcanology, geological risk, neotectonics, hydrogeology, stratigraphy palaeontology, and geological heritage) contributed to a strong case for support in the various aspects of geodiversity in the geopark. The support of the Institute of Geology, Mining and Metallurgy (INGEMMET) and the Polish Scientific Expedition to Peru (PSEP) research conducted at the same time had an important impact on the understanding of the geological structure and proved that the area represented geodiversity uniqueness at a world level [

8]. In Peru, the enthusiastic reception of the communities living in the area of the future geopark was also unusual. The project was mostly funded by the Autonomous Authority of Colca and Annexes (AUTOCOLCA) and UNESCO, with additional various contributions from the other organisations (

Table 2). Many people from local communities and Arequipa volunteered to arrange paths in the mountains, install educational boards, and mark geo-sites.

Identifying, documenting, and then promoting geotouristic values is not a simple task. A good example includes Vulkaneifel, a district located in Germany south of Bonn, where after its departure from extensive agriculture in the 1970s, tourism was promoted based on geoheritage. However, the real economic development in terms of geotourism took place 30 years later and the geopark, which belongs to UNESCO, was established in 2000 [

9].

The most difficult task for the Geopark Office is to strive to unite all communities that inhabit the area in the pursuit of development that preserves all its natural values. One of the lessons learnt at the Geopark Colca y Volcanes de Andagua is that changing the terms of office of local government officials is a great impediment, as they need to be re-convinced of their role as sustainable hosts in this land of geodiversity.

It is a challenge to convince a new political office of their responsibility to the environment on behalf of the populations of the geopark territory—both local municipalities and communities—if there is no knowledge of the value of the heritage that exists in its territory or the concept of sustainable development in a geopark.

1.3. Promotion and Expectations

The Colca Canyon and the Valley of the Volcanoes (called also Andagua Valley) area has a long history of exploring its geological heritage. It has international value demonstrated by extensive research and its promotion by Peruvian geologists and the simultaneous work of the Polish Scientific Expedition to Peru [

7]. These extensive efforts have led to the inclusion of the Geopark Colca y Volcanes de Andagua (Geopark Colca) in the UNESCO Global Geoparks (UGG) network. The UGG imposes geopark management, which considers several aspects: environmental conservation, the social and economic needs of the local populations, the protection of the landscape in which they live, and conservation of their cultural identity [

6,

10]. The goal is to connect conservation with sustainable development while involving local communities. Belonging to the UGG increases the promotion of the geopark by placing it on the list of the geologically most interesting places in the world. Thus, UNESCO strongly supports geotourism. In addition, the Geopark Colca improves the international visibility of geological attractions through a dedicated website, leaflets, and a detailed map, guides, etc.

The activities preceding the establishment of the geopark (training, seminars, conferences, and promotion) were met with very positive reactions. Organisations, local governments, and companies that deal with the organisation and service of tourist movement in the region have taken several steps to prepare their employees for activities in the geopark. The geopark office was established at the AUTOCOLCA office.

The expectations were to prepare the area for new conditions: the correction of tourist routes, preparation of new routes and attractions, promotion of regional products, and the development of accommodation and services. However, the focus of many people in Geopark Colca and Arequipa was for new jobs and the environmental and sustainable development issues were pushed to the background.

In the opinion of the community, the original plans towards the environmental and sustainable development goals that were announced and expected from the creation of the geopark being part of the UGG were forgotten.

One important and expensive investment carried out in the challenging geological conditions was the construction of the road from Huambo to Ayo and connecting the Colca Canyon with the Valley of the Volcanoes [

11]. The road was commissioned in 2019.

1.4. COVID-19

The first cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, were reported in Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei Province in China. Subsequently, COVID-19 spread rapidly across the world within months, and the outbreak was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by the WHO on 30 January 2020 and as a pandemic on 11 March 2020 [

12,

13]. The first case of COVID-19 in South America was recorded on 26 February 2020 in Brazil, and Latin America was declared a new COVID-19 epicentre on 22 May 2020 [

13]. The first case of COVID-19 in Peru was detected on 6th March 2020 [

13,

14]. According to data collected up to 4 March 2022, there have been 442,895,320 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 5,986,829 deaths assigned to it [

15].

COVID-19 continues to pose a considerable public health threat, whilst the economic [

16] and social disruptions caused by the pandemic and associated control measures are severely damaging, with tens of millions of people at risk of falling into extreme poverty and an estimated 5% increase in undernourished people globally by the end of the year.

The rapid spread of COVID-19 was also facilitated by global tourism and travel [

17]. Global travel was suddenly halted, and the tourism sector is by far one of the most affected by the COVID-19 crisis (

Figure 2).

Peru was on the list of countries under a serious threat from COVID-19 [

19]. During the pandemic, inbound outdoor tourism to Peru reduced significantly, becoming practically non-existent. Currently, there are more tourists coming to Peru. The country’s second attraction after Machu Picchu, the Colca Canyon is being reactivated with national tourism for now, and slowly with international tourism, which relies on the travel policies of each country. The local community of Geopark Colca has been serving a growing group of foreign tourists for years. So far, the promotion of places that provide people with the attractions they are looking for has played an important role. In 2019, the Canyon was visited by over 259,100 people. Foreign tourists accounted for over 50% [

20].

When analysing the impact of COVID-19 on tourism, short-term and long-term effects should be considered. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the global pathway towards the Sustainable Development Goals [

21], and the world is not on track to achieve the global goals by 2030. As the pandemic continues, its ongoing impact has been noticeable during the past year. In the first instance, the threat to health and well-being came into focus. A lack of certain medical resources and difficulties in travelling has influenced the economy, education, environment, human rights, and many other aspects at national and international levels.

Some developing countries have found themselves forced to choose between diverting scant resources towards emergency health care measures and respecting their financial capability. Others have been tempted to roll back environmental and social funds to mitigate the economic crisis caused by COVID-19 restrictions, even though this could set them back years in their sustainable development agenda.

1.5. Objectives

The economic condition of the area of this study is severely problematic and the initiatives that strengthened the bond between people and nature have been suspended. This poses a threat of returning to the chaotic use of various elements of the environment. The biggest problem is the lack of designation of functional zones in the geopark, which results in unrestricted placement of investments in the hotel and transportation industries, often at the expense of landscape and natural value protection.

The aim of the research is to discuss methods of sustainable development in the Geopark Colca y Volcanes de Andagua region to preserve its values and ensure that the forecasted return of tourism is met with sufficient preparation for its long-term success as a UNESCO geopark. A further aim of the study is to understand how the region will overcome temporary difficulties without abandoning the model of sustainable development that has been developed after a great deal of effort.

Many UNESCO geoparks are in a similar situation, especially in developing countries [

22]. What are the possible scenarios for the development of geoparks and bringing tourism back based on the prognoses taking into consideration the ongoing pandemic?

2. Materials and Methods

Since 2003, interdisciplinary research related to Earth Sciences, including geology, volcanology, spatial planning, environmental protection and engineering was conducted as outlined below:

The ongoing monitoring of the environmental and social changes in the geopark area was performed by the local community. Follow-up observations were also recorded. Official disease data from the administration and the health service in Peru were closely monitored. In addition, consultations were held with residents and representatives of the administration. The data covers the entire period of the pandemic that the government officially announced in Peru on 16 March 2020. Web interviews were carried out over the months of May and June 2020. Considering the purpose of the research, the authors prepared short and direct questions regarding the COVID-19 situation and how it has affected plans for tourism in 2020.

GIS analyses of the spatial dependencies of the spread of the virus among the inhabitants were performed. Cluster maps were used to visualise the most densely inhabited areas. The number of inhabitants was indicated, and a radius of 25 km as a distance was assumed for clarity.

3. The Events of 2020 in Peru and Geopark Colca

In addition to the illness and death of many people, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic caused a political, social, and economic crisis. The suspension of work due to national closures, mainly in large cities (Lima, Arequipa, etc.) and the lack of economic resources forced many migrants to return to their towns of origin, where at least they had their families and cultivated fields [

23].

One of the main reasons for the failure of the first Peruvian lockdown was a fragmented and under-financed healthcare system coupled with insufficient testing and vaccination [

14,

23,

24,

25,

26]. In addition, social distancing regulations were rarely followed, either intentionally [

14,

23] or because social distancing was simply physically impossible due to the living conditions in overcrowded and multigenerational households [

23,

25]. Other factors which also affected the local geopark populations include:

Deep poverty: Approximately 70% of workers were employed informally and were not eager to follow the guidelines. The Government offered financial help; however, almost 40% of the Peru population did not have a bank account, leading to crowding at banks as people attempted to open accounts to receive the governmental financial aid, possibly contributing to the further spread of the virus [

23,

25]. In Geopark Colca, such problems related to settlements such as Chachas, Choco, and to some extent, Andagua and Huambo.

Water accessibility: Over 500,000 households suffered from a lack of access to water, thus impairing handwashing as a sufficient way of combating the pandemic [

23]. In the Geopark Colca, settlements closed in high-mountain, year-round camps for llamas and alpacas.

Food source and food shopping habits: Food shopping is a daily activity for over 40% of Peruvians due to the lack of refrigerators [

23,

25], resulting in food markets contributing significantly to the COVID-19 situation. Unfortunately, most of the stores in the geopark are small facilities that are part of a family business. It is very easy to contact other people when shopping.

Political instability and economic problems: Peru has had three new presidents and several health ministers since the start of the pandemic [

23,

25]. In Peru, fake news contributed to the spread of misinformation, e.g., on self-medication, which resulted in general confusion [

26,

27]. As a result of contradictory information, the surge in the number of cases in Cabanaconde was due to a lack of discipline, and migrants who were returning on foot through the mountains to their villages were additionally hid.

Since the establishment of the geopark in 2019, only the first few months were unaffected by the pandemic. This time fell within a period that is not very attractive to tourists when rains and low day and night temperatures occur in the geopark area. Since May–September 2020, the Colca Canyon has not been visited by foreign tourists, who were the main tourists in Peru [

20].

As well as the COVID-19 problems, in June 2020, a landslide of approximately 40 ha in the Colca valley occurred. It formed a dam blocking the river flow, the waters of which flooded the riverside areas. The farmlands of the inhabitants of Achoma and Ichupampa were irretrievably destroyed, and the Chacapi geothermal pools were flooded.

4. Results

One year after the Geopark Colca y Volcanes de Andagua was established, the local community began to neglect the need to change the way of managing resources towards sustainable development. The reason was that it had not been fully aware of whether the geopark still existed or it was just a short-term action. Evidence indicates a significant risk in the role of hospitality venues—such as those providing accommodation or food and beverages—and shared modes of transport in SARS-CoV-2 transmission. High risk factors include contact patterns (close, face-to-face, extended periods of contact time, group size, activity), environmental factors (indoor, poorly ventilated), and socioeconomic factors (job insecurity, lack of community safety, lack of healthcare access). These risks are discussed below in the context of tourism in Peru and specifically in the Geopark Colca. Lastly, the COVID-19 pandemic has uncovered fragmented healthcare systems that failed to respond to the health hazard. Consequently, Peru has become the second country in Latin America, after Brazil, with the highest numbers of cases and death rates among the population. It also presents a very high number of deaths and detrimental mental states of healthcare workers [

14,

15,

23,

24,

26,

27].

More recently, Hierarchy 4 granted by the Foreign Trade and Tourism Ministry of Peru, thanks to the international denomination of UNESCO Global Geoparks, favours the improvement of actions in the short, medium, and long term in this international tourist attraction. In 2019, when the Geopark Colca population received the news of their newly designated “geopark”, a world tourism market with an increase in visitors was expected. However, effective management and governance, public-private participation, academic participation of the local universities, and the inclusion of local communities are required to promote the development of geotourism as an engine of local development that guarantees a sustainable use of the geopark, in addition to being a resilient territory to face adversities, such as COVID-19 that affects us today.

4.1. Socio-Economic Factors

Currently, tourist activities are still open in the Geopark Colca, with restrictions and the use of protocols, but it is extremely difficult for companies and agencies to prepare tourist plans, as the pandemic continues to expand and forces the issuance of temporary provisions for its control. For example, with the provision regarding a total ban on transport and commuting during the Holy Week (which coincides with the celebration of the Latin American Geotourism Day), the agencies had already prepared and promoted tourist packages for that date, whereas governmental provision dismantled all these preparations, generating unease due to the consequent economic losses.

Socioeconomic factors play a crucial role in COVID-19 prevalence and mortality, with lower education levels, median income, and poverty rates associated with cases and fatalities [

28,

29]. This may be due to crowded housing, an inability to isolate due to a lack of space or for financial reasons, low levels of car ownership among the lowest-paid workers resulting in public transport use, lower-paid occupations with reduced opportunities for physical distancing, or inequalities in access to health care.

The agricultural activities and accustomed behaviours in towns are the causes of not taking suitable preventive measures, having contact with merchants from various places, and participating in celebrations without any protection from transmission risk.

UNESCO Global Geoparks present economic opportunities for local communities [

30,

31]. The modelled estimates for Peru indicated that 27.5% of working hours were lost due to the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, when women represented 68% of employment in accommodation and food service occupations [

32]. The economic risk to local populations due to the impacts of transportation and hospitality sector closure caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which exacerbated social and economic inequalities, must therefore be considered, and actions must be taken by the geopark in preparing for the reopening. This could help to alleviate the economic risk to local populations that rely on geotourism.

It is crucial to identify and reduce risk factors of SARS-CoV-2 transmission among transport and hospitality staff, such as by providing the ability to practice social distancing, protective equipment for workplaces, appropriate return-to-work guidelines, and opportunities for self-isolation outside of the household to protect more vulnerable household members, with access to testing and healthcare facilities.

An important factor among those with lower education levels in Peru is health literacy, defined as the capacity of an individual to obtain, process, and understand crucial health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions and to address or solve a health-related problem [

27]. This, combined with the overflow of fake news, has resulted in a sense that the only way of surviving the pandemic is through self-help, self-care, and self-medication, which poses a serious risk to human health [

26,

27]. Over 90% of the studied population in Peru admitted to self-medication against COVID-19, which needs to be counteracted by raising public awareness of what SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 are, and how they can be identified, prevented, and treated [

26]. Therefore, the engagement of local populations in the geopark region is crucial to co-developing safety protocols and procedures (

Figure 3), and identifying any opportunities for education on best practices for the containment and control of COVID-19, and any future pandemic or epidemic.

4.2. Tourism Implications

The area of Geopark Colca has outstanding features which represent various forces of nature. Different fields of business—agriculture, mining, and tourism—provide a wide range of geotouristic and educational attractions. Many tourist offers include a short 2-day stay in the geopark, usually, with an overnight stay in Chivay. The main attractions are, e.g., the breath-taking display given by the Andean condors (Vultur gryphus) rising in the morning from the bottom of the Colca Canyon in Cruz del Condor, the amphitheatre of Inca cultivated terraces in Coporaque, the market in Chivay and the thermal pools in La Calera. Often, tourists set off towards Puno or Cuzco the following day. These tours are offered by offices abroad and local Arequipa companies. This option is designed for tourists who want to see many places in a short time. However, tourists would need to spend at least 7–10 days to properly visit and experience what the geopark has to offer. Chivay is the most important town and is where the geopark headquarters are located as well as numerous touristic services. However, other towns can organise tours to a limited extent. The existing road network enables travelling by car, local bus lines, but also horseback, by bike or on foot. It is standard to descend from Cabanaconde to the bottom of the Colca Canyon and stay overnight in one of the resorts.

The INGEMMET Institute carried out the inventory and valorisation of geosites in the geopark. More than 120 sites [

7] were qualified for future use by allocation into the following functions: tourist, educational, and scientific. The sites were arranged into thematic groups: geomorphology, hydrogeology, volcanology, neotectonics, geodynamics, palaeontology, stratigraphy, and structural geology. There is a high concentration of proposed sites in several locations (

Figure 4): Maca-Lari, Huambo, Ayo, and Andagua. Five sites belonging to the group of geodynamics have been identified in the vicinity of Maca and Lari. There is also one geomorphological site, another one belonging to a volcanic group, and one belonging to a stratigraphic group in the area. One geosite represents different types of information, which means that it can be visited by different interest groups. In the area where the Valley of the Volcano enters the Colca Canyon, in the immediate vicinity of Ayo, two sites have been identified for the groups of hydrogeology and structural geology, and one in the groups of geomorphology and neotectonics. The Andagua area is a locus typicus for the Andahua Group volcanoes and so there are as many as seven volcanic groups there.

Most of the geotouristic attractions of the geopark are in unenclosed outdoor spaces, presenting vast spatial geological formations with the main attraction being Colca Canyon, the deepest canyon on earth. Furthermore, sightseeing in the geopark is dominated by various geological forms and biological attractions, which provoke outdoor activities in small mobile groups. Most of the attractions do not pose any threat from an epidemiological point of view as they are outdoors. Nevertheless, some facilities associated with attractions may pose a considerable health risk. These include but are not limited to various indoor, common-use facilities such as toilets, ticket offices, and tourist information offices. Offices present transmission risks due to factors related to personal hygiene level, cleanliness of the common surfaces, number of people indoors, and room ventilation [

34,

35,

36,

37]. These facilities, as for food and beverage venues, described below, should limit the number of visitors to allow for adequate social distancing between groups of people, and to reduce the density, which is associated with viral transmission [

38,

39]. Shared toilets such as public toilets or those in hospitality venues pose a transmission risk due to the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in human faeces and urine as well as in the wastewater [

40,

41]. These may be aerosolised during flushing, resulting in airborne transmission, whilst wastewater and sewage contamination are considered as possible surveillance tools in monitoring the epidemiological situation in each area and are thus included in health risk assessments [

41,

42].

Some of the geopark’s outdoor sites, however, do attract crowds because of their nature and due to the limited space, and so they pose a direct health hazard. For example, visitors need to attend at around 8 am to see the condors taking off from the bottom of the Canyon. This causes significant crowding and chaos on observation platforms, parking lots, and artisanal stands. The accumulation of tourists cannot be overlooked at the Chivay market either, or perhaps to a lesser extent in the thermal pools. It is unclear whether geothermal pools, a type of attraction such as the ones found in Chacapi, could be contaminated with SARS-CoV-2, and it is also unclear whether transmission could occur via drinking water contaminated with viral-infected human fluids [

41,

42]. SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in rivers [

40], whilst other body fluids such as saliva may present another possible transmission route [

43,

44]. Water surveillance and contact tracing of geothermal pool visitors may identify and help reduce any transmission risks in these settings.

4.3. Travelling Implications

Due to the virus’s properties, the most important focal points for risk assessment in the touristic sector should be transportation, accommodation, and hospitality establishments, in addition to those common areas at the tourist attraction sites discussed above (

Figure 5), such as public toilets and tourist information offices.

Transport: There is evidence of an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission associated with the use of public transport due to seating proximity to an infected person, duration of time spent aboard, and inadequate ventilation, which facilitates transmission through respiratory droplets and contaminated surfaces (handles, seats) [

45].

The main modes of transport available to geopark tourists are shuttle buses—with a capacity of 15–25 passengers per vehicle—organised either by travel agencies or drivers rented from among the local community. Reducing the capacity of passengers per vehicle to facilitate social distancing in shuttle buses, as well as improving ventilation and good accessible public information, reduced public transport use, effective environmental control, respiratory etiquette, and hand hygiene is expected to reduce viral transmission, while a risk-based approach should guide the use of non-medical masks [

39].

The importance of the role of transportation in transmitting SARS-CoV-2 also depends on the distance travelled and intensity of use, where shorter distances and more frequent modes of transport pose a higher risk of infection (

Figure 4) [

39]. Although these two features do not apply to the character of transportation in the region of the geopark, an important consideration in this region is the connectivity and distance between the epicentre and destination [

39]. Tourists visit the geopark mostly for 1- to 3-day trips organised from Arequipa or from Lima, which are the biggest epicentres of COVID-19 in Peru (

Table 3). This presents an additional risk of seeding local outbreaks in local rural populations given the highly infectious pre-symptomatic phase of COVID-19, which is approximately 2 days before the onset of symptoms, whilst asymptomatic patients, those who do not present symptoms throughout the course of infection, are also able to transmit SARS-CoV-2. The proximity of local rural regions to health centres, hospitals, and testing centres makes local communities vulnerable to the negative impacts of COVID-19, particularly for those at a higher risk of severe illness, such as the elderly, pregnant women, and those with lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

In the absence of travel restrictions, local communities can also expect infected visitors to arrive from nearby epidemic areas or from overseas and there is a risk of seeding local populations with SARS-CoV-2 infections [

46], including new variants of concern that demonstrate increased transmissibility and disease severity in infected patients, and possible reduction in vaccine effectiveness. This has prompted Peru, and many other countries, to restrict travel and impose mandatory periods of self-isolation upon entering the country, whilst airlines require proof of a negative COVID-19 test for all arriving air passengers. Governments change these mandates depending on the condition of the contagions.

Hospitality: Transmission risk in hospitality venues including accommodation—such as hotels or other venues with indoor shared facilities—or food and beverage venues—such as restaurants, pubs, and bars—are due to a combination of environmental and behavioural factors [

35,

46].

The absence of hygiene interventions (such as the provision of hand-hygiene products or disposable disinfecting solutions) presents a risk for SARS-CoV-2 transmission in hospitality settings by housekeeping staff and guests [

34]. In addition, a lack of adequate ventilation systems may further contribute to the transmission and spread of SARS-CoV-2 and other airborne diseases [

47], whilst the absence of routine forward and backward contact tracing to identify potential contacts and the likely setting of transmission may reduce efforts to contain the spread of infection [

48].

4.4. Possible Scenarios of Bringing Tourism Back to Life in the Colca Geopark Region

The COVID-19 situation in Peru and the geopark region from 2020 till May 2021: Since the first case of COVID-19 was detected in Peru on 6 March 2020, the number of cases rose drastically within just two months to 129,140 confirmed cases and 7660 deaths [

13,

14,

24]. Most cases, approximately 63%, were reported in the capital city of Lima [

24]. The Peruvian Government’s reaction was quick at the time of the introduction of restrictions and was considered one of the strictest measures taken in Latin America just 10 days after detection of the first case in Peru. These included a full lockdown, closure of borders, introduction of social distancing, and even a curfew [

23,

24,

25]. Despite all these measures, Peru has become the country with one of the highest R and death rate numbers [

14,

23,

24,

25], with the virus spreading rapidly through the entire population. According to estimates on 4 March 2022, the number of reported cases of COVID-19 in Peru was 3,522,484 with 210,907 fatalities [

15]. The first case of COVID-19 in Arequipa was detected on 7 March 2020, shortly after cases were detected in the capital provinces. It continued to appear in the most remote towns (

Figure 5). In July 2020, there were already 52 cases in Chivay and 642 cases in Majes. The occurrence of the virus in the latter could be explained by the Majes district having the largest population in the province and its continuous commercial exchange with the city of Arequipa. Arequipa is the starting point of tourist movement towards the Colca towns.

Among several scenarios of bringing tourism back to life in the geopark region that can be considered, two seem worthy of more thorough analysis:

Scenario 1: The Geopark follows the Peruvian Government guidelines/rules, with the latest plan consisting of the phased reopening of Peru in 2021 [

49,

50].

There are four national alert levels in Peru developed from the most severe with the highest level of restrictions: ‘Extreme Alert Level’, followed by ‘Very High Alert Level’, ‘High Alert level’, and ‘Medium Alert Level’.

The alert levels along with their specific types of restrictions are assigned to different regions of Peru by the government based on the number of current COVID-19 cases and death rates, which are reviewed every three weeks. No further specification is provided on transmission thresholds for changes to the alert level in a given region. The alert levels are more detailed regarding indoor activities and indoor facilities, whereas outdoors remain very similar across the alert levels. According to these, the geopark attractions can be open to the public no matter what alert level is currently present. Moreover, although the alert levels are very specific regarding indoor facilities’ operations and limits, they do not mention hotels and offices, e.g., tourist information centres, which are crucial for the geopark reopening for tourism. Due to high levels of COVID-19, the Peruvian Government announced on 8 May 2021 the extension of emergency self-quarantine and movement restrictions for three more weeks. These were effective as of Monday, 10 May 2021 to 30 May 2021, then were extended till 20 June 2021. The region of Arequipa and the geopark were considered on the High Alert level.

Scenario 2: As an extension of Scenario 1, the geopark plays an active role in securing tourists’ and local people’s health in addition to adhering to the Government guidelines. A significant role of the UNESCO Global Geoparks is to promote sustainable local economic development through a bottom-up approach through partnership and cooperation with local stakeholders. It is therefore important to engage with the local community to promote a two-way conversation on the risks and benefits of the possible scenarios to reopening the geopark region to tourists, from a public health perspective, but also from an economic perspective. This scenario requires substantial support and cooperation from key stakeholders including the local community, the Peruvian Government, the geopark’s network, travel agencies, and public health officials.

Health and safety is a key factor considered by many tourists especially during the pandemic and should be included in the promotion of the region to show that it is an important sustainable development issue that has been considered. There are several measures that can be introduced within the geopark region to improve the safety of the geopark for the local community and tourists as the region reopens as a travel destination. For example, there could be an organised information campaign informing people on what COVID-19 is and how to best protect from it. Information posters are now displayed prominently in local governmental offices, tourist offices, and health care facilities, which should be promoted as a reliable source of knowledge for the local community and for tourists. A communication network could be established between all medical points in the region, with central points at the hospitals in Majes (even though it is not within the geopark, it does serve the Colca residents due to its proximity to Orcopampa). These points should actively exchange information on the COVID-19 situation in their regions (such as infection rates, available hospital beds, vaccine stock, available personal protection equipment) and promote these resources to tourists. These hospitals must also be equipped to attend COVID-19 cases. Hotel, transport, and restaurant staff should be trained and evaluated every six months in COVID-19 prevention methods. Some locations mentioned previously, such as the Cruz del Condor viewpoint, the market in Chivay, or the geothermal pools (La Calera and Chacapi) would require coordination of several bodies, such as geopark administration, travel agencies, hotels, restaurants, and other facilities, to avoid the congestion of tourists such as by limiting parking spaces to reduce visitor numbers. Such a coordination would be very important in these localities, where large crowds gather in a small area in a short timeframe and overcrowding may occur.

For future epidemic and pandemic preparedness, is it also crucial that strategies and activities put in place by the geopark communities to support the local government’s efforts to protect public health and the local economy should be adequately recorded, and a follow-up consultation with local communities should promote an active discussion on the ‘lessons learnt’.

5. Discussion

UNESCO initiated discussions regarding the conservation of human heritage, culture, and the protection of human rights in the early phase of the pandemic, which in some ways helped the international and local communities to prepare for the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the United Nations agencies and UNESCO cooperated closely with governments to engage in creating better action plans in the crisis for a better coordination of resources and actions.

UNESCO, together with its global field offices, sites, and different programmes, took responses from multiple dimensions to build and raise resilience and capacity to mitigate the influences and further respond to the disaster. UNESCO provided advice for policy development, implementation, and developing institutional and human capacities in spite of the sudden changes to the modes of communication, which shifted rapidly online. Several programmes and toolkits were released by UNESCO (

Table 1) to ensure the continuity of learning and education. This engaged a variety of stakeholders including the general public, local communities, and public authorities in culture conservation and STI, strengthening international cooperation. Digital forums took place to continue the undone work and discuss the transformation of the digitisation of social interaction, and thus reshaped the economic and social sectors.

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed or deepened differences in society caused by persistent and growing inequalities between people, countries, and businesses. The impact of the crisis caused by the pandemic has varied considerably due to unequal initial conditions, and while some people could switch to remote working in times of confinement, and even improve the quality of their lives, others have lost the chance for a better future.

One important lesson learnt from the COVID-19 pandemic is that it cannot be solved by using a disciplinary or sectoral approach and that the political leaders and decision-makers must embrace new inclusive approaches due to the complex interlinked challenges. This will require an interdisciplinary approach to design holistic sustainable solutions by using the full spectrum of the social and natural sciences, as well as indigenous knowledge, and the applied fields including engineering. Engineering and technological innovations require such interdisciplinary approaches and are vital in poverty eradication and in emergency and disaster response, mitigation, and reconstruction.

For 2021, the aim was to contribute to a sustainable international recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic in order to rebuild tourism for the future, within the framework of strengthened multilateralism. The future of the tourism industry is not very optimistic. Uncertain forecasts such as the UNWTO’s extended scenarios for 2021–2024 show that it could take 2.5–4 years to return to the tourism sector condition as it was in 2019.

One of the UNESCO Global Geopark’s goals is to ensure health and well-being for all: the local population and visitors. This goal has been prioritised due to the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure continued educational and sustainable development and tourism activities in the newly shaping post-pandemic world. Furthermore, the local community and the condition of the healthcare system must be taken into consideration. The considerations discussed here are also applicable to other geoparks across the world which have been affected by the rapid spread of the virus [

22]. Data from Peru confirm that the prevalence and occurrence of the novel coronavirus is highest in more densely populated areas such as large cities, which is a trend often seen across the world. The highest numbers of cases and deaths are recorded in the capital city of Lima and the second biggest city of Arequipa, which is closer to the geopark.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Geopark Colca y Volcanes de Andagua missed out on the opportunity for an exceptional opening as a new geo-attraction on the global map of UNESCO Geoparks. Local economic growth was expected from tourists, especially those looking for geodiversity. The social costs of preparations for this season were exceptionally high. Invaluable commitments from the local volunteers have also not been included in any of the reports.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought serious socioeconomic losses and emotional distress for the Geopark Colca y Volcanes de Andagua community. The additional natural disaster, the landslide in Maca, only deepened the disappointment. The organisation of the geopark administration, which relies on revenues from visitors’ tickets, fell into crisis. Losses in the tourism sector have increased unemployment and poverty in the region, and the idea of sustainable development implemented within the geopark has in fact perished.

6. Conclusions

The creation of the Geopark Colca y Volcanes de Andagua in 2019 was preceded by many years of scientific exploration. Subsequently, the consolidation of the local communities was carried out, which often had to change their way of lifestyle to protect and display the geoheritage and natural values of the area. In order to meet the high requirements of the UNESCO Global Geoparks Network, the area’s community had to adhere to the principles of sustainable development. To do this, state funds and private funds were mobilised, and work for the geopark on a voluntary basis was widely applied. All with the hope of a better life in the future geopark.

The COVID-19 crisis brutally halted the geopark’s activities in its infancy. A concern for the health and life of the citizens forced the Peruvian government to pursue social policy at the expense of maintaining sustainable development. All of the key elements of the geopark (communities, offices, social associations, and touristic agencies) have only one goal now—to survive. This means the inhibition of sustainable development, degradation of the ecological awareness of the inhabitants, and return to the old style of living regardless of environmental resources and achieved environmental goals.

Keeping the restrictions at the highest level threatens to deepen the economic crisis associated with a significant increase in poverty and misery. The result of restrictions at the highest level alone have also been shown not to prevent further virus outbreaks due to the lack of adequate infrastructure. Lifting restrictions too early, without immunising most of the geopark community (possibly due to pressure from desperate employers and employees in the tourism, hospitality, transportation, and leisure businesses) threatens to promote the emergence of new virus outbreaks. The lack of a stronger vaccination programme will likely lead to another wave, which could culminate during the most favourable weather conditions and related peak of touristic activity in this part of the Andes.

If borders are re-opened and about 25% of tourists from the pre-pandemic period are admitted, this means a significant increase in the risk of disease introduction in the local population. The key issue is, therefore, the level of preventive vaccinations of the local community, assuming that all arriving tourists would also be vaccinated. Intuitively, the local community will be afraid of contact with “strangers”, but the risk of infection and severe disease will constantly be greater in contacts between unvaccinated geopark residents.

Despite a number of doubts, especially of a financial nature, we recommend scenario 2 in which the organisational structure of the geopark is actively involved to inform, organise help for residents and tourists, and put extra measures in place tailored specifically to the needs of such a unique region. Assuming that it is not possible to expand medical care in a short time, it is important from the point of view of the health of local communities scattered in the mountain area and the incoming tourists.

It seems that the Geopark Institution is being given a new task: to contribute to local communities on how to protect from COVID-19. For the Geopark Colca y Volcanes de Andagua, the key consideration is how to strengthen its administrative structure and management—namely, the main office located currently in Chivay which, due to the lack of tourists, lost its scope. It needs to be structurally and financially strengthened. UNESCO’s organisational aid seems to be within reach due to the active and engaged community of other geoparks in the network who willingly share good practices from their experiences. In order for Geopark Colca to survive the crisis, which also means maintaining geological, natural, and cultural values, significant outside help is needed. Additional help from the UNESCO Global Geoparks Network is also needed, which has a unique opportunity to demonstrate the relationship between its headquarters and its geopark members across the world. In practice, this means the continuation and strengthening of the process of implementing sustainable development and raising environmental awareness and sensitivity to the values of Geopark.

COVID-19 is not the first, nor the last, pandemic to affect the geopark stakeholders. Although the pandemic is still not over, some important lessons already learnt could be directly implemented for this region. The most important lesson of all is that communication between local authorities, healthcare representatives, local communities, neighbouring regions, and, crucially, the government, must be quick, reliable, and effective. This is essential for a coordinated, rapid, and effective response.