A Storytelling Methodology to Facilitate User-Centered Co-Ideation between Scientists and Designers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Compartmentalization of Scientists’ and Designers’ Expertise

- Finding applications for new technologies and scientific research outcomes by ideating and visualizing use scenarios;

- Unlocking scientists’ tacit or implicit knowledge (knowledge that is difficult to articulate or present tangibly [41]), challenging their perceptions, and stimulating new ideas or research direction through design artefacts;

- Creating technology prototypes for testing and experimentation;

- Assisting with the communication and dissemination of research through the visualization of scientific ideas.

1.2. Storytelling as a Design Method to Facilitate Co-Creation between Scientists and Designers

1.3. Positioning of This Research

2. Theoretical Background and Fundaments of Our Storytelling Method for Co-Ideation and Three-Tension Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participatory Story Building Workshops

- 1.

- Scoping

- 2.

- Preparation

- -

- data on user needs or problems (e.g., user interviews, user personas, experience flow, clinical insights, social and lifestyle trends);

- -

- technology insights (e.g., technology basics, current or envisioned technology applications, technology trends);

- -

- business and market insights (e.g., benchmarking and business landscape around technology or solutions for the unmet need).

- 3.

- Workshop

- Knowledge sharing: specialists share their insights, and, if possible, real users describe their experience around the scoped need. Re-acting of the user experience is sometimes used to achieve a deeper understanding and empathic feel of the situation. This phase is plenary, and then the participants split into sub-teams of 3–4 people for the rest of the workshop.

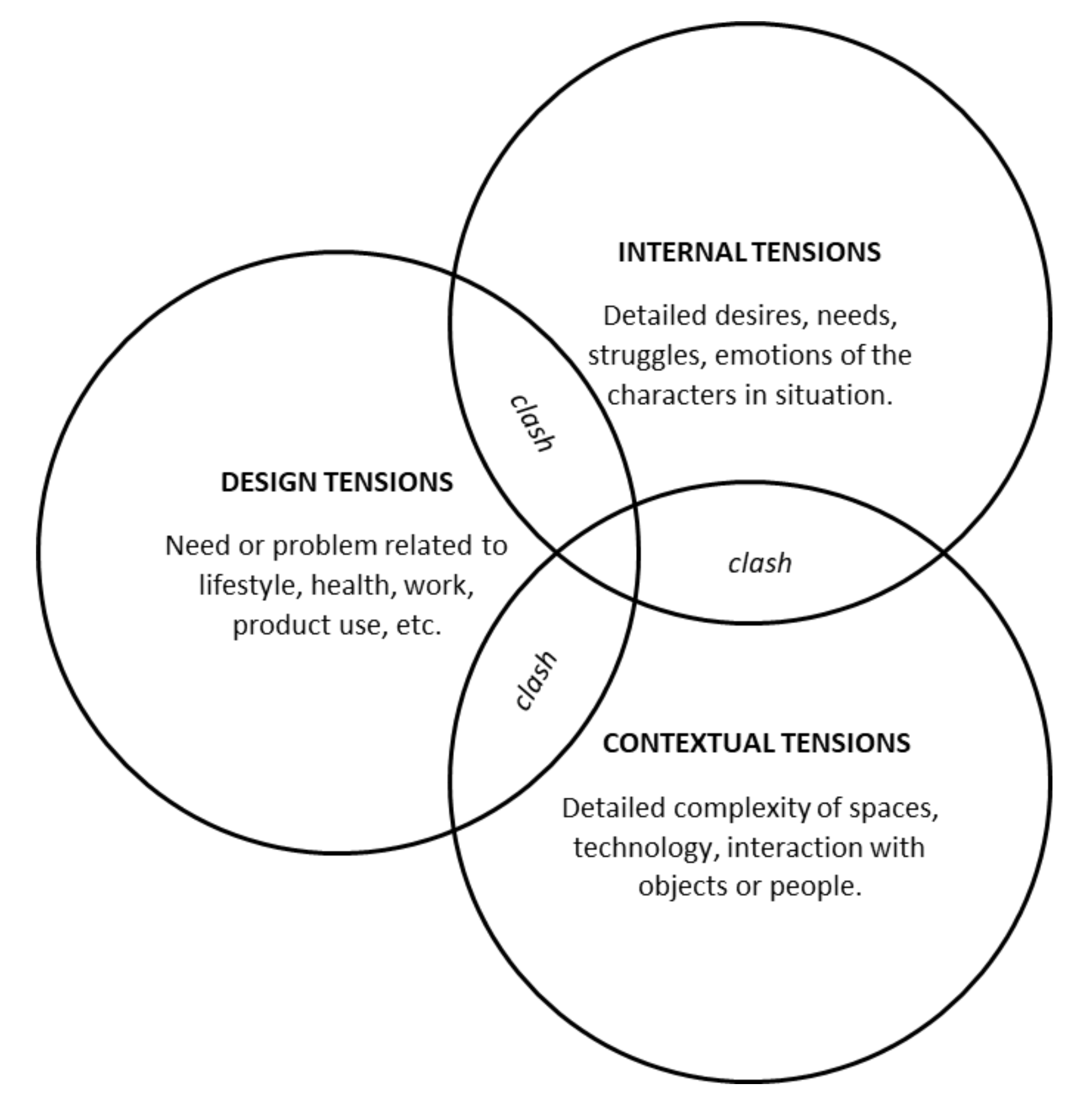

- Imaginary personas are built by the participants using detailed templates that ask questions about the character’s life, past, and expectations, based on the 3-tensions framework (Figure 2). The personas are a combination of real insights gathered from the knowledge sharing and imagination. If some aspects of the persona are too unrelatable for the participants (for example, if they are care professionals or users from different cultures), the personas can be partially worked out before the ideation by a team of designers, and a story is told around the multiple tensions of the personas to introduce them in the workshop.

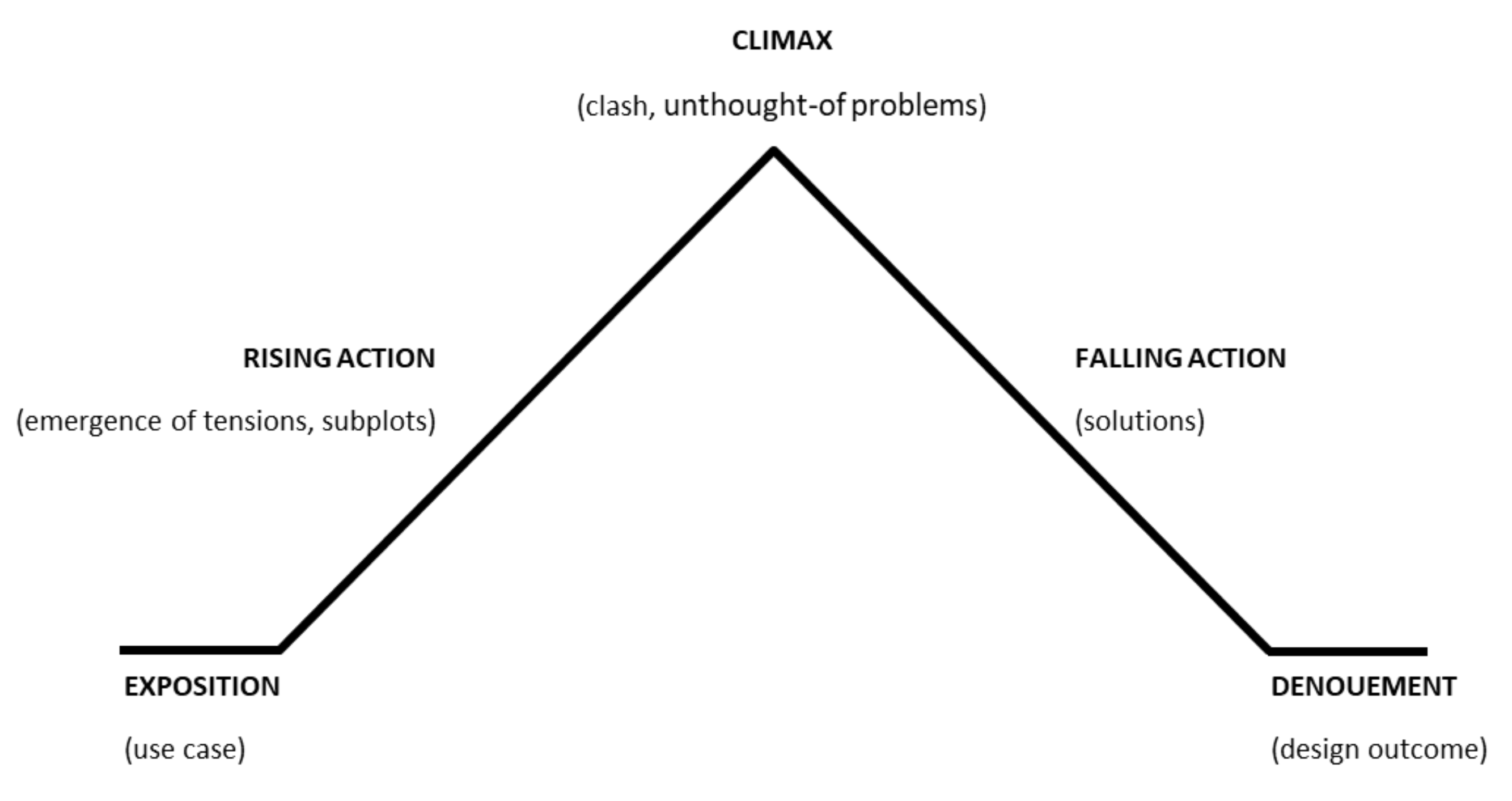

- The story arc is built following a basic story arc structure (Figure 3) [68]. The story arc can be collectively sketched on a board, in some cases using pre-defined templates. The participants use real needs and problems of users gathered from the knowledge sharing and add imaginary struggles to build a story. They discuss how the personas feel and react for each problem in the journey. To solve the problems arising in the story, solutions may be inserted that use the technology. The participants detail the interaction between the user and the solutions, making new problems emerge. If the stories take place in contexts that are unrelatable for the participants (for example, specific to some professions or cultures), story pieces highlighting problems can also be worked out before the ideation and the participants use these to ideate on how the story unfolds.

- Storytelling and enrichment: each team shares plenarily their persona(s) and story to the other teams. This can be done by (a combination of) speech, body storming, acting out, mocking up, scripting, video recording, or writing a short story, depending on the use case and the participants’ level of comfort with the technique. Some methods are more suited for certain use cases (e.g., scripting works well for conversational interfaces, body storming for gesture-based interaction). After the story is shared, the participants discuss the moments in the story that are unexpected, such as a surprising use of the technology, a surprising persona’s behavior, an unthought-of need or problem.

- 4.

- Idea filtering

3.2. Data Collection

- The first workshop was held in August 2018 face-to-face and consisted of 9 participants: 4 designers (including 2 of the authors of this paper, who facilitated the workshop), 4 scientists, and 1 clinical specialist. Of these, we interviewed 2 designers and 2 scientists.

- The second workshop was held in July 2019 face-to-face with 14 participants: 6 designers (including 2 of the authors, who facilitated the workshop), 5 scientists, and 4 business and market stakeholders. Of these, we interviewed 3 designers, 3 scientists, 1 business lead, and 1 market lead.

- The third workshop was held in March 2021 fully digitally and consisted of 10 participants: 4 designers (including 1 of the authors, who facilitated the workshop), 5 scientists, and 1 clinical specialist. Of these, we interviewed 2 designers and 2 scientists.

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

- Enabling multidisciplinary creative collaboration (seven themes);

- Promotion of user-centered thinking (three themes);

- Range and type of generated ideas (three themes);

- Relevance of the tool in innovation (four themes);

- Impact on mindset, perception, and way of working of participants (two themes).

4.1. Enabling Multidisciplinary Creative Collaboration

“When you come together with designers, with people in business, with people from research, I think that is where, you know, that’s where the Magic happens”.(a scientist)

“It’s good to kind of mix them up a bit and, then again, because the way the method is scripted, you kind of empower everybody. Doesn’t matter who contributes, it’s not like a math problem where only the engineers are happy because they’re consulted, and others feel left out”.(a scientist)

“I felt all ideas or train of thoughts were very well encouraged. So there was no judgement. And I think potentially the storytelling helped there, because we were like thinking about: oh yeah, a fictive character. Yeah. So it was not that there was one specific idea based on previous experience or an interview that may be invalid; everything was possible because it referred to a specific, fictive person”.(a designer)

“I feel like otherwise you will easily get trapped in a more technological discussion, potentially also hindered by what is possible and what’s not possible this far”.(a designer)

“What often happens and especially when you’re so deep in the topic, […] you create this one directional way of thinking […] and then it’s always good, once in a while, to have other people looking at that completely differently so that you know: OK, I have to open up again because I’m focusing too much again on the topic […] I think it happens in any cocreation session. But I think what happened here is because of the storytelling”.(a scientist)

“We came up with crazy stuff. […] as researchers can be, they can be very excited about a specific detail, and then when they put it into a story, it’s actually quite an interesting concept or idea”.(a designer)

“The flow of the workshop was very natural, and it helped to align and to find common ground in thinking about these ideas”.(a designer)

“Normally you have a workshop and then people say OK start brainstorming. It’s not a button!”.(a scientist)

“I’m bad at drawing and you know I would do it. But telling a story or coming up with a story is actually maybe a lower threshold for a lot of people, so […] you have more people in the creative mindset”.(a designer)

“It makes people curious, […] they started to have fun. I felt empowered, excited. […] I was at a party!”.(a scientist)

“So for me these were quite exhausting days. You have to be really engaged and that engagement, yeah, it takes quite a quite a lot of energy if you want to be fully engaged. I’m also a fan of like this workshop event and you need it if you really want to get something done. I was happy to engage, engage with the team”.(a scientist)

“I think it this famous thing of taking people out of their comfort zone. I think you can definitely achieve that with this approach. Because it takes them out of the technology bubble or the doctor bubble or whatever bubble they’re in, it takes them out of that bubble and it forces them to try to take that other perspective, even if it’s only for a few hours”.(a designer)

4.2. Promotion of User-Centered Thinking

“It’s a completely different angle than this technology push, this is something I think that we do too much in research, that we have a certain technology and then we’re going to look: OK, where does it fit? Now we have a problem, and whatever technology or method can be applied there is all open, and I think that’s my sort of takeaway message. […] This is also, yeah, almost the most important thing if you want to create something for people; you first have to study the people that you’re designing for, developing for”.(a scientist)

“Many designers initially are very much thinking about […] cool stuff they can make, but not always useful ones. […] It’s more in the line of thinking ‘because we can’, not necessarily because it’s going to help users”.(a designer)

“What I think it really brings is having to step out of the theoretical sphere and really look at something that gives you more information, more point of view from practice. So that’s one, and the other is actually having to think about people. So really, the story is about a person and you have to use empathy; you have to project your point of view from the point of view of that person. So that’s also something that’s really strong in this methodology”.(a designer)

“Let’s not understand them [the personas] as an object, but try to understand them from the inside out. Well, that’s what storytelling does”.(a designer)

“You’re forcing people to think what the consequences are of doing this. And yeah, you sort of might find out that the consequence doesn’t work unless you do something. So, to me, that’s always been the strongest part of the storytelling”.(a scientist)

4.3. Range and Type of Generated Ideas

“It was a kind of a pressure cooker workshop, so I was impressed by the number of ideas we had in so little time”.(a designer)

“It’s richer, it maybe gives you more avenues for coming up with ideas […]. You start to see: oh yeah, well, this might connect with this and there’s a whole story around it. So then you say: oh well, I can approach it from different angles”.(a scientist)

“I think that the quality was a bit less than I expected, but that was compensated by the amount”.(a designer)

4.4. Relevance of the Tool in Innovation

“I sometimes see that they created technology and after that, they start looking: OK, so what kind of problem can I solve? […] Often you also see that ending up in the bin”.(a scientist)

“There are many different stakeholders, and I think something like this would really help everybody get more awareness about what the problem is”.(a scientist)

“Sometimes […] if you look at the specific idea like that, it’s quite specific or random. But now, because he told the story, you can actually see how it came to be and what it’s like in context”.(a designer)

“I still think that finding the problem is sort of the unique part of it. And I’m sure there are other ways to do the other things [finding solutions], but I don’t think there are a lot of other ways to force the problems”.(a scientist)

4.5. Impact on Mindset, Perception, and Way of Working of Participants

“[before the storytelling workshop] my mindset was also, let’s come up with something, let’s invent, let’s try design or create and then test. Now I first start, OK What do we need to show? What’s the key problem that we need to solve? I think that really changed in my perception”.(a scientist)

“My mindset has I think a bit opened. You can see that there are other ways to collaborate and ideate […] in general more than what we normally do in Design, right? We always have the same types of workshops. And I think this really shows that there is room for innovation here as well to come up with new ways of doing this”.(a designer)

“I was again confirmed afterwards that [the scientists] really like this kind of thing […] it’s kind of like a little school trip for them. We get to go to Design!”.(a designer)

5. Discussion

5.1. Storytelling for Inclusive and Creative Multidisciplinary Collaboration

5.2. Storytelling to Integrate User-Centered Thinking in the Innovation Community

5.3. Perception of the Collaboration and the Other Discipline

6. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Supplementary Information on the Data Collection

- What do you remember from the workshop [date and topic of the workshop]?

- Do you think that the storytelling method brings anything?

- Let’s talk about the concrete outcome: how would you describe the resulting ideas? Do you think they were different, better or worse, and how, than ideas from other brainstorms?

- What tools do you usually use to do creative ideation? Do you get stuck somewhere where you think storytelling could help?

- How did you experience the storytelling workshop, how did you feel during the workshop?

- How did your experience the collaboration between designers and scientists during the workshop?

- Has your perception of designers/scientists, their role and their contribution to innovation changed after the workshop? If yes, how?

- Has your perception of user-centered thinking changed after the workshop? If yes, how? [only for scientists]

- Has your mindset or your way of working changed after the workshop? If yes, how?

- Do you have any other remarks, or a recommendation for improvements?

| Number of Scientists’ Quotes in This Theme | Number of Designers’ Quotes in This Theme | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Enablement of multidisciplinary creative collaboration | 1. Multidisciplinary | 21 | 12 |

| 2. Inclusiveness | 12 | 8 | |

| 3. Common language | 6 | 10 | |

| 4. Engagement | 21 | 15 | |

| 5. Accessibility | 5 | 11 | |

| 6. Creativity | 4 | 9 | |

| 7. Out of comfort zone | 6 | 5 | |

| Promotion of user-centered thinking | 8. User centered | 16 | 16 |

| 9. Persona | 9 | 11 | |

| 10. Scenario | 18 | 10 | |

| Range and type of generated ideas | 11. Range of ideas | 9 | 3 |

| 12. Quantity of ideas | 6 | 4 | |

| 13. Quality of ideas | 9 | 2 | |

| Relevance of the tool in innovation | 14. Where in the innovation process | 9 | 2 |

| 15. Business relevance | 9 | 1 | |

| 16. Communicating to others | 1 | 3 | |

| 17. Problem | 15 | 1 | |

| Impact on mindset, perception, and way of working of participants | 18. Changed way of working | 18 | 11 |

| 19. Changed perception | 8 | 8 |

| Theme | Conclusions | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Multidisciplinary (bringing different people and expertise together) | Almost all participants stated that, in ideation, it was beneficial to bring together different perspectives and disciplines (research, business, design) and to set up a collaboration space where everyone could chip in with their expertise and insights. The interdisciplinary approach facilitated looking at problems from different angles and generating more varied insights. The storytelling facilitated this multidisciplinary collaboration. | “When you come together with designers, with people in business, with people from research, I think that is where, you know, that’s where the Magic happens” (a scientist) |

| Some differences between scientists and designers were highlighted, such as scientists looking more at how products work while designers looked at how products are used. One scientist and one designer recognized that there is a stereotyped perception of designers amongst scientists, where designers make “things look pretty” and think more “out of the box, creative and free-form”, and that designers are not always considered when solutions have to be generated. | “And I think it can help to make it a bit easier with people who are bit skeptical of the sort of skill sets that design brings to the table. Or you know, like I know there is a kind of stereotype in research that design, like if you want to get a pretty image or do something that looks pretty then you go to design. But if you really want to solve a problem then you wouldn’t. Design won’t always be invited to the table” (a scientist) | |

| 2. Inclusiveness (giving everyone an equal voice) | There was consensus that the storytelling method enabled inclusiveness with respect to expertise or perspective, because every participant could easily translate their perspective through a story. It did not put more emphasis on the input of one particular person or group of persons with a given expertise—in contrast to workshops focused on one type of expertise, where participants with another type of expertise find it difficult to speak up. For example, in a technology-focused workshop, it might be difficult for non-technical people to contribute. In contrast, designers are often more talkative than scientists, who tend to internalize their thinking, which can create an imbalance. The storytelling method prevented having a dominant person or group taking over the discussion. Rather, people enhanced each other’s ideas. | “It’s good to kind of mix them up a bit and, then again, because the way the method is scripted, you kind of empower everybody. Doesn’t matter who contributes, it’s not like a math problem where only the engineers are happy because they’re consulted, and others feel left out” (a scientist) |

| It was suggested that storytelling broke down barriers for people to speak up because of the fictional nature of the character—everything was possible. All ideas or trains of thought were encouraged; there was no judgement—in contrast with other types of ideation that are framed in reality, where specific ideas can more easily be invalidated. | “I felt all ideas or train of thoughts were very well encouraged. So there was no judgement. And I think potentially the storytelling helped there, because we were like thinking about: oh yeah, a fictive character. Yeah. So it was not that there was one specific idea based on previous experience or an interview that may be invalid; everything was possible because it referred to a specific, fictive person” (a designer) | |

| One participant said that storytelling is more objective than ideation based on marketing results, because marketing personas bring in a bias while imaginary personas give more freedom when imagining their response. | ||

| 3. Common language during workshop | Most interviewees acknowledged that storytelling helped participants communicate their ideas in an understandable way because they were embedded in a story’s context. People with different expertise think very differently—for example, workflows or other design methods might be difficult for scientists to comprehend—while everyone can grasp a story and add to it. It got participants on the same page, gave them common ground, and helped them look at things from different perspectives. | “Today so many people do this with these, you know, workflows or other design methods that we have. But I can imagine that for scientists it’s actually quite hard to comprehend. And then the story, that’s something that basically everyone can grasp and then add to” (a scientist) |

| Storytelling is a fun and common language that created a natural conversation flow. The conversations were started more easily. | “The flow of the workshop was very natural, and it helped to align and to find common ground in thinking about these ideas” (a designer) | |

| Scientists tend to go into details quickly, and the storytelling helped to keep a golden thread through the discussion. | “I think it really is hard to put words to it, but I really think it helps them to not go into too much detail not to feel like they’re out of their depth […] it’s just having a kind of a lifeline to hold up through this story” (a designer) | |

| 4. Emotional engagement during workshop | In general, the participants perceived the workshops as fun, playful, laid-back, relaxed, and exciting, with a positive and energizing atmosphere. They were highly engaged and motivated to participate and empowered in providing contributions. | “It makes people curious, […] they started to have fun. I felt empowered, excited. […] I was at a party!” (a scientist) |

| Several factors were mentioned that contributed to this high engagement. First, playfulness helped participants to bond—the story building acted as an icebreaker that helped to take people out of their comfort zone. Second, people were motivated to participate beforehand; they were curious. Several participants suggested that the method was exciting and engaging because it was a new method—people might be tired of “classical” post-it-based brainstorms. Third, the introduction presentations were of high quality and enjoyable. | ||

| Several interviewees said that there was a good flow that made the workshops less exhausting than other workshops. | ||

| One scientist found the real-life workshop tiring because of the continuous and high-energy engagement required; still, they were happy to engage with the team. For the online workshop, which was shorter, one scientist mentioned that there was too much time pressure and another scientist felt that the “flow of emotion” and the interaction between people was not optimal. | “So for me these were quite exhausting days. You have to be really engaged and that engagement, yeah, it takes quite a quite a lot of energy if you want to be fully engaged. I’m also a fan of like this workshop event and you need it if you really want to get something done. I was happy to engage, engage with the team” (a scientist) | |

| 5. Accessibility of method (cognitive engagement during workshop) | It was clear from the answers that building or telling a story has a low threshold for people. “Everybody watches movies”, so it was very easy to for people to understand the method. The process of story building had clear guidelines, which made it very easy to understand what to do. It was a quick way to get people on board, to put people in the right mood and creative mindset. The process happened naturally; it did not feel like a typical ideation session. | “I’m bad at drawing and you know I would do it. But telling a story or coming up with a story is actually maybe a lower threshold for a lot of people, so […] you have more people in the creative mindset” (a designer) |

| Several interviewees mentioned that good preparation of the workshop, some conditioning of the participants beforehand, and a good introduction to give background information on the methodology were key enablers for success. The introduction on storytelling already helped to trigger discussion, instead of a classical ideation in which participants must start brainstorming when told to. | “Normally you have a workshop and then people say OK start brainstorming. It’s not a button!” (a scientist) | |

| However, the process was difficult for some participants. One scientist said that it was sometimes a lot to follow and that he needed mental breaks. One designer mentioned that writing a story from the user’s perspective is very difficult, because people like to make statements that fit into their own worldview and stick to their field of expertise. Moreover, the ability to be empathetic is very person-dependent. There is a need to bring people into a true people-centric and storytelling mindset, and the designer hypothesized that a one-day workshop might not always be enough to achieve this change. | “You really need to sort of change the mindset of people in order for them to be able to understand what it is that you’re trying to do” (a designer). “Sometimes there was a bit too much in the sense that I could not follow. I had to take a mental break” (a scientist) | |

| 6. Creativity (triggering outside-the-box thinking—a different approach to ideation) | Because the stories were imaginary, participants thought outside the box more easily. Storytelling facilitated out of the box ideas by taking away barriers—such as focusing on what is technically possible or not—and favored an open, creative mindset. | “I feel like otherwise you will easily get trapped in a more technological discussion, potentially also hindered by what is possible and what’s not possible this far” (a designer) |

| Participants combined these out-of-the-box, unexpected ideas with expertise, resulting in exciting new directions. It also facilitated the combination of ideas and formation of connections that would not be seen otherwise. | “We came up with crazy stuff. […] as researchers can be, they can be very excited about a specific detail, and then when they put it into a story, it’s actually quite an interesting concept or idea” (a designer) | |

| Designers and scientists expressed that, for someone who has been working on a topic for a long time, using the storytelling method with people who look at the topic in a different way brings a new perspective and enables a different way of thinking. It happens to some extent in any co-creation session, but the storytelling enhances this new perspective taking. A participant also mentioned that storytelling can help when one gets stuck in an ideation stage. | “What often happens and especially when you’re so deep in the topic, […] you create this one directional way of thinking […] and then it’s always good, once in a while, to have other people looking at that completely differently so that you know: OK, I have to open up again because I’m focusing too much again on the topic […] I think it happens in any cocreation session. But I think what happened here is because of the storytelling” (a scientist) | |

| Besides the active story building process, just listening to a story triggered discussion. | “So someone was telling a story about a certain situation and then you saw that on the other side of the room. Another one said like, Oh yeah, but how about you doing this? Or how would you do that?” (a designer) | |

| 7. Out of comfort zone and of usual way of working | Storytelling is not something that people do daily; it took participants out of their comfort zone. It forced them to step out of their bubble of expertise (technical, design, clinical, etc.) because the stories were all-encompassing. Furthermore, it involved brainstorming with different disciplines, which is not always common practice and was “refreshing”. | “I think it this famous thing of taking people out of their comfort zone. I think you can definitely achieve that with this approach. Because it takes them out of the technology bubble or the doctor bubble or whatever bubble they’re in, it takes them out of that bubble and it forces them to try to take that other perspective, even if it’s only for a few hours” (a designer) |

| For designers, storytelling is close to what they usually do and feels natural to their generally more extrovert or creative nature. | ||

| Scientists normally work based on literature, data, and evidence, and storytelling allowed them to think beyond that. This could be helpful, for example, in coming up with ecosystem solutions, which are usually broader than the one activity on which a typical expert focuses on. | ||

| In business, ideations are not common, but they usually integrate the customer perspective by using market analysis tools such as analytics data or customer reviews. From these, they evaluate where they can improve to come up with the next steps in the product and business models. Tools such as storytelling are also used in marketing. However, ideations are usually organized around existing activities or current business operations, with specifiable problems statements, and are aimed at imagining propositions to solve these problems. Our storytelling methodology is different because it focuses on problem finding or need-seeking. It is a complementary approach to traditional brainstorms, where participants spend most of the time coming up with potential solutions. | “The strongest part is problem finding or need-seeking aspect and that’s really different to any other workshop. It sometimes surprises me that you come up with inventions because actually you don’t spend a lot of the workshop focusing on the invention” (a scientist) | |

| 8. User-centered mindset (meaningful vs. technical) | All participants mentioned that the method helped in bringing a user perspective to the ideation. For most of the interviewees, this was a contrast from other ideations that very often start from a specific technology, a use case related to that technology, or a technological problem. The scenarios in the storytelling workshop did not address a technical capability. They made people focus holistically on the whole customer experience and needs and on the usage of the product in real-life scenarios. By doing so, they helped to improve on the interaction, usability, attractiveness, and usefulness of a product for an audience. | “It’s a completely different angle than this technology push, this is something I think that we do too much in research, that we have a certain technology and then we’re going to look: OK., where does it fit? Now we have a problem, and whatever technology or method can be applied there is all open, and I think that’s my sort of takeaway message. […] This is also, yeah, almost the most important thing if you want to create something for people; you first have to study the people that you’re designing for, developing for” (a scientist) “Many designers initially are very much thinking about […] cool stuff they can make, but not always useful ones. […] It’s more in the line of thinking ‘because we can’, not necessarily because it’s going to help users” (a designer) |

| Storytelling brought the ideas that the participants have with the perspective and context of the user in mind. It enabled the determination of whether ideas are relevant and practical or not. | “What I think it really brings is having to step out of the theoretical sphere and really look at something that gives you more information, more point of view from practice. So that’s one, and the other is actually having to think about people. So really, the story is about a person and you have to use empathy; you have to project your point of view from the point of view of that person. So that’s also something that’s really strong in this methodology” (a designer) | |

| Especially for scientists, technologists, and developers, it is difficult not to forget to bring the user in, to consider the emotional benefits and other design aspects. Forcing them to be in the shoes of the persona made the emotion of the journey flow in a more natural way. Many interviewees mentioned that scientists thoroughly enjoy being brought out of their technological sphere to a user-centered perspective (be it storytelling workshops, field trips, or discussions with real users). | “I deal with a lot of developers and they are really good at putting a certain functionality in the app code and they just push it in. But then it makes more sense to also look at the customer, how the customer actually uses this feature” (a business lead) | |

| Several designers mentioned that designers also can have a technological mindset and may lack the user-centered focus when approaching ideation: they initially think about what they can make—because it is “cool” and because “they can”—but not necessarily about useful products that would help users. | “I feel like otherwise you will easily get trapped in like a more technological discussion” (a designer) | |

| 9. Persona (stepping in the user shoes and building empathy) | The benefit of using the detailed personas in the process was clearly acknowledged. Focusing on a specific persona’s life (e.g., a patient, a care professional) helped participants take different perspectives, to take the user’s point. The story brought the personas to life. It forced participants to think about how their ideas may fit into that specific individual’s journey, what would their real-life experience be, issues, and relationships with other people. By “being in the shoes” or “being in the skin” of a particular type of persona, participants understood them deeply and truly empathized. | “Let’s not understand them [the personas] as an object, but try to understand them from the inside out. Well, that’s what storytelling does” (a designer) |

| It helped to have different personas (e.g., several types of users) to obtain different perspectives and make the participants aware of the differences, and then to focus within a breakout team on one persona. It prevented getting stuck with a specific persona’s issue and targeting the ideas around that issue. | ||

| Empathizing with the user through the use of personas led to identification of realistic ideas and opportunities. | ||

| 10. Scenario (acting out and in context) | Going through scenarios, into the real-life situation of a persona using or experiencing an existing or future product or service, did help ideation. It triggered discussion and inspired people to come up with new ideas. Several interviewees compared it to experiencing a real product. It forced the participants to think about the consequences of their ideas in real life and see what works or not in reality. A business interviewee wished that going into experience scenarios would be used more often in development processes. | “You’re forcing people to think what the consequences are of doing this. And yeah, you sort of might find out that the consequence doesn’t work unless you do something. So, to me, that’s always been the strongest part of the storytelling” (a scientist) |

| Several participants stated that ideating based on scenarios did not feel like a typical way of ideating where one finds solutions for a problem, but that it embedded the relevant context around the problem. | “[usually] this is the problem and now solve it. Right, so I think that’s more, I don’t know, it’s like in a vacuum that is presented normally and now it’s not a vacuum. You have all of the data sort of around it.” (a scientist) | |

| A designer expressed that scenarios are a better way to share user insights than the experience flows typically used in user research. He explained that experience flows are difficult to comprehend because they are too rich—unless one is already very deep in the topic—and that people get lost in the details. On the contrary, he said that scenarios are a way to tailor the experience data that one wants to share. | “You’re tempted to put the whole thing [experience flows] because A, that’s what you have and B, everything is in there. So basically, it’s not tailoring your methodology to what’s exactly needed, but just taking what you have; either nothing or not fitting. And that’s what I experience with this process. It fits exactly because you made the story and all the inputs specifically for this process, and that works really well” (a designer) | |

| Another benefit mentioned is that participants were able to map their own experience on the topic onto the story. | ||

| It appeared that the fact that participants embodied a situation not by using words, but by using gestures and acting out, made them experience a certain problem at a different level. | “And that was a very hands-on workshop. So it wasn’t just storytelling, it was really what do you call it? Body storming or something like that? So we really acted out scenes and […] I think that that’s the thing I remember most about that, when I think compared to other sessions I’ve been involved in, we acted out more scenarios and that was really, really useful” (a scientist) | |

| Several designers and scientists noted the importance of having the scenarios based on enough real experience data gathered, e.g., from interviews or psychological research data. At the same time, they did not need to be perfectly accurate if they were a support or ideation, but rather described a “day in the life” of the persona with enough depth to trigger ideation. A designer suggested to back the story building with more scientific evidence in terms of psychology. | “And also there if you get 80% right, it’s fine. It’s fine, and if your story wasn’t 100% perfect, you get some weird ideas or anything, […] it doesn’t really matter, so there’s a big gray area in how accurate your story has to be, as long as it’s a good story and gives you a lot of cues to ideate on. And it did” (a designer) | |

| 11. Range of ideas (broader scope, different type) | Most interviewees—especially scientists—stated that the scope of ideas was broader, and the ideas were more diverse than in usual ideation sessions. This was attributed to the participants in the brainstorms thinking about situations or areas that they did not consider exploring beforehand—in contrast with a traditional approach, where the problem is very scoped, and the boundaries are very well defined. | “It’s richer, it maybe gives you more avenues for coming up with ideas […]. You start to see: oh yeah, well, this might connect with this and there’s a whole story around it. So then you say: oh well, I can approach it from different angles” (a scientist) |

| Interviewee answers converged to say that storytelling is about seeing the big picture. The ideas were more connected to other services or platforms because participants thought more broadly and beyond the main problem. The range of ideas was also broader because storytelling makes the participants less hindered by what is possible and what is not possible this far. | ||

| Scientists and designers recognized that the storytelling set-up is oriented at creating UX ideas, which made them different from ideas generated in traditional brainstorms because creating user experience ideas is uncommon. | ||

| 12. Quantity of ideas | Many interviews stated that the storytelling workshops were very productive; they generated more ideas than traditional ideation. | “It was a kind of a pressure cooker workshop, so I was impressed by the number of ideas we had in so little time” (a designer) |

| 13. Quality of ideas (high level, more thought-through, farfetched) | Some participants thought that the ideas were more thought-through, while some thought that the ideas were less complex and less concrete than with other ideation methods. The idea quality and value seemed to benefit from the fact that participants enhanced each other’s ideas through the storytelling process. The lowest complexity would come from the fact the participants did not go really deep in detailing the ideas, but rather focused on the situation and on the experience. A one-day workshop was too short to bring the high-level ideas to detailed propositions, and the rough ideas needed to be worked out in more detail afterwards. A scientist missed the technological depth during the ideation but was able to chip in later when the ideas were deepened. | “Yeah, so I think they these are more thought through. [In traditional workshops], the ideas are typically from like one or two people initially, so the background of the idea is typically very small. In the storytelling workshop everyone is aligned in the story, and we give input in the story I feel the background for the ideas is a lot richer” (a scientist) “Yeah, maybe the complexity of the ideas is lower that you come up. Which is maybe also one of the weaknesses of the approach. You know you don’t, you never go really deep, you go very deep in the situations and in the experience” (a scientist) |

| Several scientists and designers observed that even if, initially, the quality of the raw ideas was heterogeneous, after selection, there were more high-quality, high-value ideas than in a typical brainstorm because of the large number of ideas generated. | “I think that the quality was a bit less than I expected, but that was compensated by the amount” (a designer) | |

| One interviewee found that some ideas were more far-fetched than usual, which he attributed to storytelling bringing participants out of their comfort zone. | ||

| 14. Where in the innovation process | Many scientists regretted that, in innovation environments, the fundamental reason for developing a technology is not always there. The approach in product innovation is too often to draft a technology, to go through the development process, and finally to position the product in the market by looking at the problems it can solve. This approach may result in low resonance of the product with the users and a potential product fail. It is important to first identify the user problems, which is what the storytelling methodology does. Storytelling can be used to identify the user’s problems that should be solved by a technological innovation. | “I sometimes see that they created technology and after that, they start looking: OK, so what kind of problem can I solve? […] Often you also see that ending up in the bin” (a scientist) |

| Several scientists found that storytelling is a good tool for exploration, at the start of the innovation journey. | ||

| A scientist and a designer thought that storytelling can enhance the experiential, visual brainstorm around a real product or a wireframe by making problems from a user perspective more visible. It can help to replace this type of physical brainstorm in digital, remote brainstorms. Storytelling could be used as a pre-test in early prototypes to gather preliminary user insights before testing with real users. | “If you can’t touch the apparatus and be there in the hospital and see what it is, by telling the story you bring the problems more to life. […] I think storytelling can maybe help compensate a bit [for the virtual collaboration that is a challenge]” (a scientist) | |

| One scientist said that storytelling can be used for product roadmap building: it enables ideation on future users’ target groups and their pain points, which can then be prioritized and used to set the scene for a solution roadmap ideation. | ||

| One scientist said that storytelling helps for ecosystem innovation, where there is no clear existing business, or any defined problems (an area where traditional methods would not suffice). | ||

| Another angle mentioned by several scientists was that by identifying new problems, storytelling can help find new general solutions for certain needs that are novel enough to allow patentability. | ||

| 15. Business relevance | According to the interviewees, the main business benefit of storytelling is its collaborative power. Storytelling can help bring various teams and stakeholders together to bring awareness about the real issues of the user and how to solve them, in order to understand the relevant gaps or opportunities to be pursued. | “There are many different stakeholders, and I think something like this would really help everybody get more awareness about what the problem is” (a scientist) |

| One scientist said that storytelling forces people to come up with propositions rather than standalone solutions. | ||

| One interviewee working in marketing thought that storytelling can support marketers in understanding how real users would use a product, in order to optimize the customer fit or to validate certain marketing ideas. Moreover, businesses often focus on the biggest target group that can yield the best revenue, but storytelling can help identify new, maybe smaller, customer groups with high margins. One designer shared similar thoughts that storytelling can help in finding new markets for a product or a technology by taking an existing product out of context to unexpected application areas. | ||

| 16. Conveying/communicating ideas to others outside the workshop | Some scientists and designers mentioned that stories are a good way to communicate information and ideas—for example, when following up or reporting on some concepts. It is easier to explain the idea and how it came to be in the context of a story and from the perspective of a person. | “Sometimes […] if you look at the specific idea like that, it’s quite specific or random. But now, because he told the story, you can actually see how it came to be and what it’s like in context” (a designer) |

| 17. Problem ideation | Most of the scientists appreciated that the method forces issues and conflicts to focus the ideation and create the solutions. If participants stay in the “happy flow” of the story, there is no problem and there is nothing to solve. The storytelling makes problems of the user and the causes of those problems more visible and tangible. By introducing problems and dilemmas in the scenarios, participants feel the struggle that the users may have in daily life; they discover new issues and pain points during product use, and eventually come up with new ideas. | “The issue that a person is facing, and if you can capture that well and you have also to say that in confidence this is an issue that we need to tackle, then start the ideation. It should be, I would say, almost the method or the standard method for ideations” (a scientist) |

| Several interviewees said that storytelling is a unique and powerful tool for finding problems and is a complementary method to other tools for solution ideation. | “I still think that finding the problem is sort of the unique part of it. And I’m sure there are other ways to do the other things [finding solutions], but I don’t think there are a lot of other ways to force the problems” (a scientist) | |

| Only the scientists and no designers mentioned problem ideation as an aspect of the storytelling method. | ||

| 18. Changed way of working and mindset after the workshop | The workshop showed that there is room for new ways to collaborate and ideate and triggered many participants to learn more about different tools related to storytelling. | “My mindset has I think a bit opened. You can see that there are other ways to collaborate and ideate […] in general more than what we normally do in Design, right? We always have the same types of workshops. And I think this really shows that there is room for innovation here as well to come up with new ways of doing this” (a designer) |

| The workshop was a trigger for most of the scientists to start implementing design tools in workshops. such as persona, metaphors, system maps, on top of the traditional ways of brainstorming they were already using (TRIZ, etc.). The storytelling method made them realize or reinforced their perception that there is value in taking a user-centered approach and in starting ideation from problems instead of technology. Only one scientist did not change their WoW or mindset after the workshop. | “[before the storytelling workshop] my mindset was also, let’s come up with something, let’s invent, let’s try design or create and then test. Now I first start, OK What do we need to show? What’s the key problem that we need to solve? I think that really changed in my perception” (a scientist) | |

| After the workshop, several designers started using personas and empathic story-building tools to incorporate the experience part to a higher degree into their design research work or in their communication. A designer explained that many designers tend to leave out the emotional part and that storytelling can fill this gap. | ||

| After the workshop, several scientists and business stakeholders reported that they encouraged their teams to try and use products and prototypes to get a realistic feel and share their experience. | ||

| A scientist explained that the way of working and ideating in innovation has changed completely in the last 5 years, from “inventing a device in a box” to a blend of digital, ecosystem, and hardware, and that storytelling is needed in this new innovation mindset. | ||

| 19. Changed perception of others after the workshop | Most participants did not significantly change their perceptions of the other roles (scientist, designer) because they had interacted or worked together in the past. | |

| However, several participants better understood the roles of people with other expertise, realized the value of having different types of expertise work together, and were triggered to do it more in future projects. | ||

| Several designers were surprised and realized that scientists can be creative and excited about this type of ideation. | “I was again confirmed afterwards that [the scientists] really like this kind of thing […] it’s kind of like a little school trip for them. We get to go to design!” (a designer) |

References

- Puerari, E.; De Koning, J.I.J.C.; Von Wirth, T.; Karré, P.M.; Mulder, I.J.; Loorbach, D.A. Co-Creation Dynamics in Urban Living Labs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barile, S.; Grimaldi, M.; Loia, F.; Sirianni, C.A. Technology, Value Co-Creation and Innovation in Service Ecosystems: Toward Sustainable Co-Innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sopjani, L.; Hesselgren, M.; Ritzen, S.; Janhager, J. Co-creation with diverse actors for sustainability innovation. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Engineering Design, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 21–25 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L.; Bour, R.; Kostense-Smit, E.; Muller, J.; Huibrechtse-Truijens, A.; Hekkert, M. Barriers to the Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rocchi, S. Designing with Purpose—A Practical Guide to Support Design & Innovation in Addressing Systemic Challenges around Health & Wellbeing for All; Koninklijke Philips: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dokter, G.; Thuvander, L.; Rahe, U. How circular is current design practice? Investigating perspectives across industrial design and architecture in the transition towards a circular economy. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 26, 692–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, S.; Niwa, K. Pioneering Customer’s Potential Task in Innovation: Separation of Idea-Generator and Concept-Planner in Front-End. In Proceedings of the 2006 Technology Management for the Global Future—PICMET 2006 Conference, Istanbul, Turkey, 8–13 July 2006; pp. 2025–2036. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, B. A conceptual history of innovation. In The Elgar Companion to Innovation and Knowledge Creation; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, A.; Peralta, C.; Moultrie, J. Exploring how industrial designers can contribute to scientific research. Int. J. Des. 2011, 5, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kurvinen, E. How industrial design interacts with technology: A case study on design of a stone crusher. J. Eng. Des. 2005, 16, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexfelt, O.; Selvefors, A. The Use2Use Design Toolkit—Tools for User-Centred Circular Design. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.; Verganti, R. Incremental and Radical Innovation: Design Research vs. Technology and Meaning Change. Des. Issues 2014, 30, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verganti, R. Radical design and technology epiphanies: A new focus for research on design management. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2011, 28, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.; Mohr, J.; Sengupta, S. Radical Product Innovation Capability: Literature Review, Synthesis, and Illustrative Research Propositions. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsiepe, G. The Uneasy Relationship between Design and Design Research. In Design Research Now; Basel, B., Ed.; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2007; pp. 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Peralta, C.; Moultrie, J. Collaboration between designers and scientists in the context of scientific research: A literature review. In Proceedings of the 11th International Design Conference, DESIGN 2010, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 17–20 May 2010; pp. 1643–1652. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, C. Design Enquiry: Tacit Knowledge and Invention in Science. Des. Issues 2004, 20, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, J.R.; Malassigné, P. Lessons learned from a 10-year collaboration between biomedical engineering and industrial design students in capstone design projects. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2017, 33, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rust, C. Unstated contributions—How artistic inquiry can inform interdisciplinary research. Int. J. Des. 2007, 1, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ruckstuhl, K.; Costa Camoes Rabello, R.; Davenport, S. Design and responsible research innovation in the additive manufacturing industry. Des. Stud. 2020, 71, 100966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinel, M.; Eismann, T.; Baccarella, C.; Fixson, S.; Voigt, K.I. Does applying design thinking result in better new product concepts than a traditional innovation approach? An experimental comparison study. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, C.P. The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Milewski, A.E. Software engineers and HCI practitioners learning to work together: A preliminary look at expectations. In Proceedings of the 17th Conference on Software Engineering Education and Training, Norfolk, VA, USA, 1–3 March 2004; pp. 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. On the Essential Contexts of Artifacts or on the Proposition That “Design Is Making Sense (of Things)”. Des. Issues 1989, 5, 9–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazman, R.; Gunaratne, J.; Jerome, B. Why can’t software engineers and HCI practitioners work together? In Human-Computer Interaction Theory and Practice; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.; Brady, S.; Sutcliffe, S.; Smith, A.; Mueller, E.; Rudser, K.; Markland, A.; Stapleton, A.; Gahagan, S.; Cunningham, S. Converging on Bladder Health through Design Thinking: From an Ecology of Influence to a Focused Set of Research Questions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlgren, L.; Elmquist, M.; Rauth, I. The Challenges of Using Design Thinking in Industry—Experiences from Five Large Firms. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2016, 25, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Damera-Venkata, N.; Liu, J.; Lin, Q. When Engineers from Mars Meet Designers from Venus: Metacognition in Multidisciplinary Practice; Hewlett-Packard Development Company, L.P.: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Koen, P.; Ajamian, G.; Boyce, S.; Clamen, A.; Fisher, E.; Fountoulakis, S.; Johnson, A.; Puri, P.; Seibert, R. Fuzzy Front End: Effective Methods, Tools, and Techniques. In The PDMA Toolbook 1 for New Product Development; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Herstatt, C.; Verworn, B. The ‘Fuzzy Front End’ of Innovation. In Bringing Technology and Innovation into the Boardroom; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2004; pp. 347–372. [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury, L. The Race to the Top: A Review of Government’s Science and Innovation Policies; HM Treasury: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlström, A. Storytelling in Design: Defining, Designing, and Selling Multidevice Products; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois-Bougrine, S.; Latorre, S.; Mourey, F. Promoting creative imagination of non-expressed needs: Exploring a combined approach to enhance design thinking. Creat. Stud. 2018, 11, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruen, D.; Rauch, T.; Redpath, S.; Ruettinger, S. The use of stories in user experience design. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2002, 14, 503–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Han, S.; Kwahk, J. A MORF-Vision Method for Strategic Creation of IoT Solution Opportunities. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2018, 35, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesenbery, W.; Brooks, K. Storytelling for User Experience—Crafting Stories for Better Design; Rosenfeld Media: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, P. Storytelling and the development of discourse in the engineering design process. Des. Stud. 2000, 21, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turilin, M. Radical Innovation of User Experience: How High Tech Companies Create New Categories of Products; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Verganti, R.; Öberg, Å. Interpreting and envisioning—A hermeneutic framework to look at radical innovation of meanings. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M. Knowledge (Explicit, Implicit and Tacit): Philosophical Aspects. Int. Encycl. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 13, 74–90. [Google Scholar]

- Charyton, C.; Jagacinski, R.; Merrill, J. CEDA: A Research Instrument for Creative Engineering Design Assessment. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2008, 2, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, A.; Hoegl, M. Organizational Knowledge Creation and the Generation of New Product Ideas: A Behavioral Approach. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 1742–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, E.; Tardini, S.; Cantoni, L. Lego Serious Play applications to enhance creativity in participatory design. Creat. Business. Res. Pap. Knowl. Innov. Enterp. 2014, 2, 200–210. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, E.; Stappers, P. Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wattanasupachoke, T. Design Thinking, Innovativeness and Performance: An Empirical Examination. Int. J. Manag. Innov. 2012, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Liedtka, J. Perspective: Linking Design Thinking with Innovation Outcomes through Cognitive Bias Reduction. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 32, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füller, J.; Hutter, K.; Faullant, R. Why Co-Creation Experience Matters? Creative Experience and Its Impact on the Quantity and Quality of Creative Contributions. RD Manag. 2011, 41, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, G.C.; DeMartino, R. Organizing for Radical Innovation: An Exploratory Study of the Structural Aspects of RI Management Systems in Large Established Firms. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2006, 23, 475–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruoslahti, H. Complexity in project co-creation of knowledge for innovation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2020, 5, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, K.O.; Katri, V. Innovation Ecosystems as Structures for Value Co-Creation. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2019, 9, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- West, R. Communities of innovation: Individual, group, and organizational characteristics leading to greater potential for innovation: A 2013 AECT Research & Theory Division Invited Paper. TechTrends 2014, 58, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jagtap, S.; Warell, A.; Hiort, V.; Motte, D.; Larsson, A. Design Methods and Factors Influencing their Uptake in Product Development Companies: A Review. In Proceedings of the DS 77: 2014 13th International Design Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 19–22 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bairaktarova, D.; Bernstein, W.; Reid, T.; Ramani, K. Beyond Surface Knowledge: An Exploration of How Empathic Design Techniques Enhances Engineers Understanding of Users’ Needs. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2016, 32, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Hatchuel, A.; Le Masson, P.; Weil, B. Teaching innovative design reasoning: How concept-knowledge theory can help overcome fixation effects. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. 2011, 25, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichaw, D. The User’s Journey: Storymapping Products That People Love; Rosenfeld Media: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Parrish, P. Design as storytelling. TechTrends 2006, 50, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genco, N.; Johnson, D.; Hölttä-Otto, K.; Seepersad, C. A Study of the effectiveness of the Empathic Experience Design creativity technique. In Proceedings of the International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 28–31 August 2011; pp. 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Mostafa, N.; Han, H.J. “StoryWeb”: A storytelling-based knowledge-sharing application among multiple stakeholders. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2020, 29, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buskermolen, D.O.; Terken, J. Co-constructing stories: A participatory design technique to elicit in-depth user feedback and suggestions about design concepts. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Roskilde, Denmark, 12 August 2012; pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kankainen, A.; Vaajakallio, K.; Kantola, V.; Mattelmäki, T. Storytelling Group—A Codesign Method for Service Design. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2012, 31, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeeva, N.; Trifilova, A. The role of storytelling in the innovation process. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2018, 27, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpong, D.; Maclean, M. Mobilising differential visions for new product innovation. Technovation 2012, 32, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckler, S.A.; Zien, K.A. From experience the spirituality of innovation: Learning from stories. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1996, 13, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, R.; Giuliani, A. A Narrative Perspective on Entrepreneurial Opportunities. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 38, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djajadiningrat, J.; Gayer, W.; Frens, J. Interaction Relabelling and Extreme Characters: Methods for Exploring Aesthetic Interactions. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques, New York, NY, USA, 17–19 August 2000; pp. 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Brem, A.; Tidd, J.; Daim, T. Managing Innovation: Understanding and Motivating Crowds; World Scientific: Singapore, 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Freytag, G.; MacEwan, E. Freytag’s Technique of the Drama: An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art, 6th German ed.; MacEwan, E.J., Translator; Scott: Chicago, IL, USA; Foresman, IN, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.; Marconi, V. Code Saturation versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qual. Health Res. 2016, 27, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; APA Handbooks in Psychology®; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J.; Buisine, S.; Aoussat, A.; Gazo, C. Generating prospective scenarios of use in innovation projects. Trav. Hum. 2014, 77, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward, T. Structured Imagination: The Role of Category Structure in Exemplar Generation. Cogn. Psychol. 1994, 27, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviselvam, S.; Subburaj, K.; Hölttä-Otto, K.; Wood, K.L. Systematic Application of Extreme-User Experiences: Impact on the Outcomes of an Undergraduate Medical Device Design Module. Biomed. Eng. Educ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedmon, A.W.; Winslow, R.; Langley, A. Micro-generation schemes: User behaviours and attitudes towards energy consumption. Ergonomics 2013, 56, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talgorn, E.; Hendriks, M. Storytelling for systems design—Embedding and communicating complex and intangible data through narratives. In Proceedings of the Relating Systems Thinking & Design (RSD) Symposium, Delft, The Netherlands, 2–6 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gersie, A. Storytelling for a Greener World; Hawthorn Press: Stroud, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Bellon, D.; Kane, A. Natural history films raise species awareness—A big data approach. Conserv. Lett. 2020, 13, e12678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Talgorn, E.; Hendriks, M.; Geurts, L.; Bakker, C. A Storytelling Methodology to Facilitate User-Centered Co-Ideation between Scientists and Designers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074132

Talgorn E, Hendriks M, Geurts L, Bakker C. A Storytelling Methodology to Facilitate User-Centered Co-Ideation between Scientists and Designers. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):4132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074132

Chicago/Turabian StyleTalgorn, Elise, Monique Hendriks, Luc Geurts, and Conny Bakker. 2022. "A Storytelling Methodology to Facilitate User-Centered Co-Ideation between Scientists and Designers" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 4132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074132

APA StyleTalgorn, E., Hendriks, M., Geurts, L., & Bakker, C. (2022). A Storytelling Methodology to Facilitate User-Centered Co-Ideation between Scientists and Designers. Sustainability, 14(7), 4132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074132