The Prosocial Driver of Ecological Behavior: The Need for an Integrated Approach to Prosocial and Environmental Education

Abstract

:1. Opening

2. Rationale

3. Research Hypothesis and Goal

4. Method

4.1. Indicator of Prosocial Propensity

4.2. Measures

- The sentimentality scale of the HEXACO personality inventory [21] in the emotionality domain was used as an indicator of empathy. We used Russian and Spanish versions of the scale, consisting of 4 items, provided at www.hexaco.org. The items were either identical to the original scales or amended to optimize their linguistic fluency in Russian and Spanish (Table A1).

- The Rushton et al. [27] scale measured altruistic behavior. Items on this scale required self-reporting altruistic behavior and were thus conceptually similar to the items on the ecological behavior scale. A small number of items on the scale were modified to better reflect Russian and Latin American culture and geography (Table A3).

- Connection to humans was measured with the scale specified in [13]. We used the “People in my community” option of the original scale, while the other two options (“Americans” and “People all over the world”) were dropped because we considered them too broad for the purpose of the study.

- Connection to nature was measured via an additional response option added to the McFarland et al. (2012) scale. Specifically, we used the additional option “Natural surroundings” to complement the original scale option “People in my community”. Assessing connection to nature with this type of measure allowed us to evaluate connection to various domains using the same question stems, thus enabling better comparisons between them. The items in scales (4) and (5) were either identical to the original scale of [13] or amended to optimize their linguistic fluency in Russian and Spanish (Table A4).

4.3. Sample Population

4.4. Data Analysis

4.5. Scale Reliability

4.6. Scale Validity

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Empathy as an Indicator

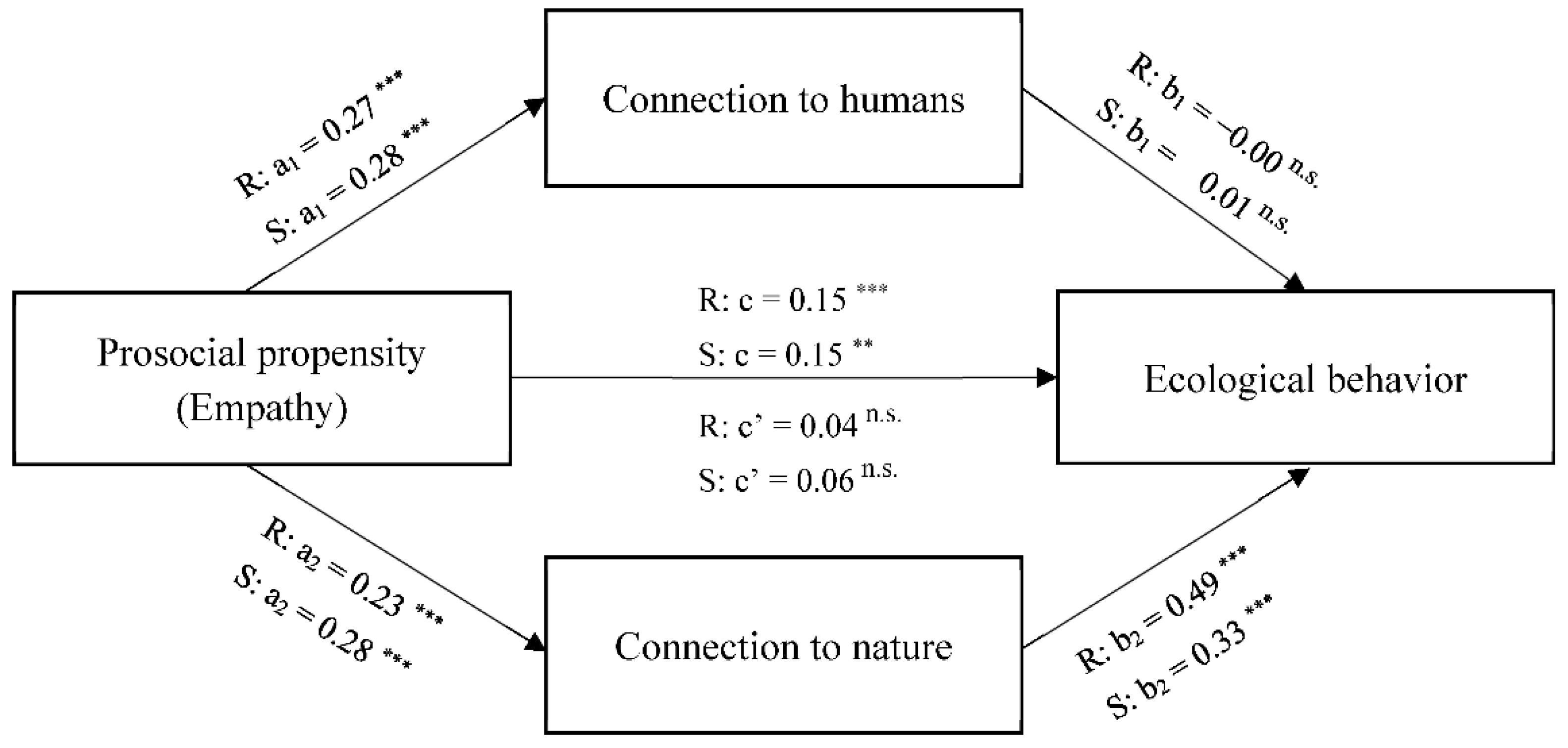

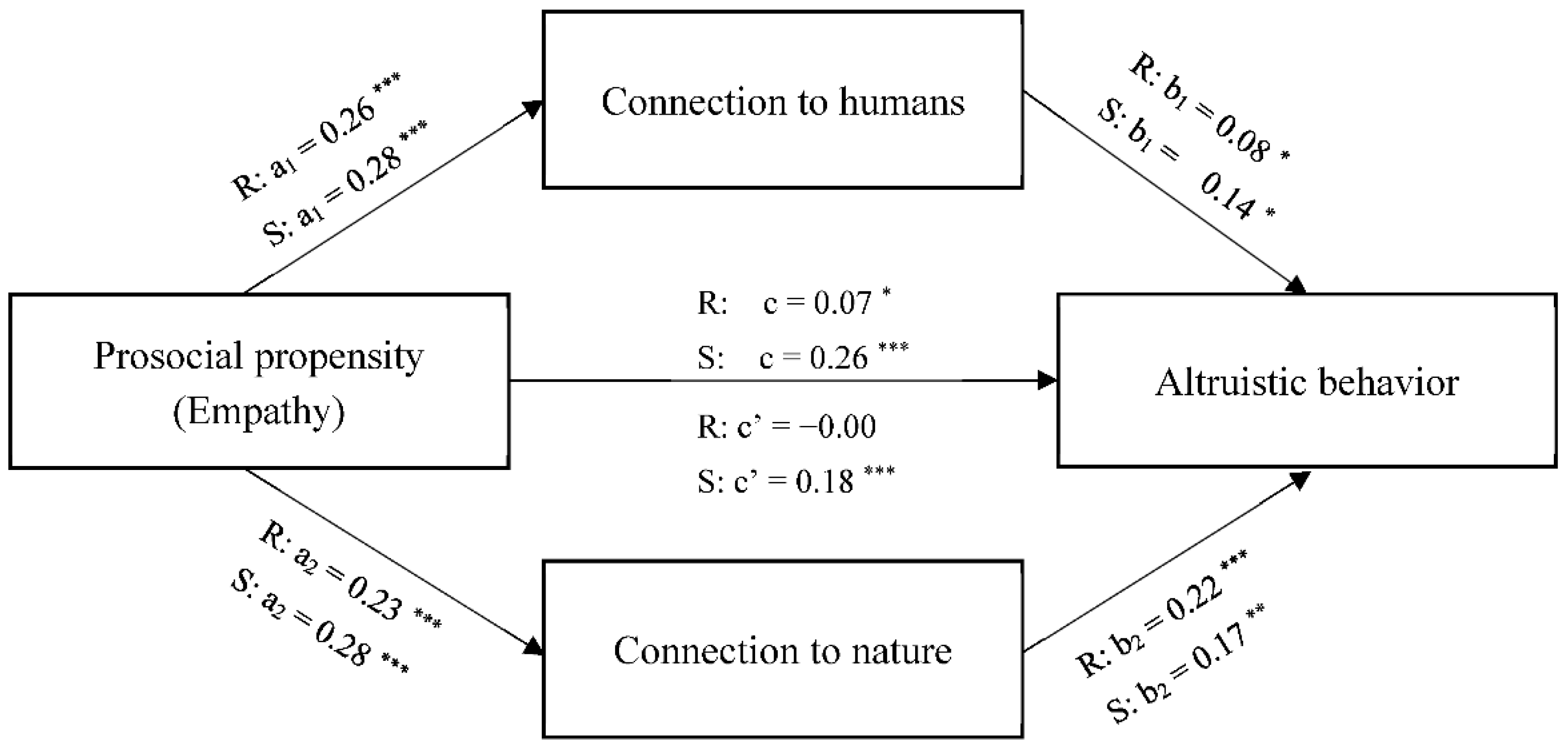

5.2. Mediation Effects

5.3. Reanalysis of a Previous Study

5.4. Differences between the Russian and Spanish Samples

5.5. Possible Mechanisms, Limitations, and Future Directions

5.6. Implications from an Educational Perspective

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| English Translation | Spanish Items | Russian Items |

|---|---|---|

| S23. I feel like crying when I see other people crying. | S23. Siento ganas de llorar cuando veo llorar a otras personas. | S23. Готов(а) заплакать, если вижу плачущего человека. |

| S47. When someone I know well is unhappy, I can almost feel that person’s pain myself. | S47. Cuando alguien muy cercano a mí es infeliz, casi puedo sentir el dolor de esa persona. | S47. Остро переживаю несчастья моих близких. |

| S71. I feel strong emotions when someone close to me is going away for a long time. | S71. Siento emociones fuertes cuando alguien cercano a mí se va a alejar por un largo tiempo. | S71. Страдаю от долгих расставаний с близкими. |

| S95. I remain unemotional even in situations where most people get very sentimental. | S95. No me emociono incluso en situaciones donde la mayoría de las personas se ponen muy sentimentales. | S95. Сохраняю хладнокровие даже в ситуациях сильного эмоционального напряжения. |

| English Translation | Spanish Items | Russian Items |

|---|---|---|

| 1. I turn off the TV, computer, and other electrical devices when I’m not using them. | 1. Apago el televisor, computador y otros artefactos eléctricos cuando no los utilizo. | 1. Выключаю телевизор, компьютер и другие электроприборы, когда ими не пользуюсь. |

| 2. I buy natural products and/or products with ecolabels (e.g., cleaning products, shampoos, etc.). | 2. Compro productos naturales y/o con sello ecológico (por ejemplo, detergentes, champúes, etc.). | 2. Покупаю натуральные/эко продукты/товары (например, моющие средства, шампуни и т.д.). |

| 3. I buy drinks or beer in disposable containers (plastic or cans). | 3. Compro bebidas o cervezas en envases desechables (plástico o lata). | 3. Покупаю напитки в одноразовой таре (пластиковой, металлической). |

| 4. I wait until I have a full load before doing laundry. | 4. Espero a tener una carga completa de ropa antes de usar la lavadora. | 4. Накапливаю белье до полной загрузки стиральной машины. |

| 5. When I shower, I turn the water off while I soap up and then turn it back on to rinse. | 5. Cuando me ducho, cierro el agua para jabonarme y finalmente abro el agua para enjuagarme. | 5. Выключаю воду в душе во время намыливания и снова включаю для ополаскивания. |

| 6. I read about environmental issues. | 6. Leo acerca de temas ambientales. | 6. Интересуюсь экологическими проблемами. |

| 7. I buy products in reusable packaging. | 7. Compro productos con envases reutilizables. | 7. Покупаю товары в многоразовой упаковке. |

| 8. I shop using my own reusable bags. | 8. Hago compras usando mis propias bolsas reutilizables (por ejemplo, bolsas de género). | 8. Отправляясь за покупками, беру с собой собственные многоразовые сумки/пакеты. |

| 9. I use public transportation, ride my bike, or walk to get around my neighborhood. | 9. Para desplazarme dentro de la ciudad, utilizo el transporte público o la bicicleta, o camino a pie. | 9. Передвигаюсь по городу на общественном транспорте, велосипеде или пешком. |

| 10. I recycle or reuse used paper. | 10. Reciclo o reutilizo el papel usado. | 10. Отправляю в переработку и повторно использую старую бумагу. |

| 11. I recycle or reuse glass bottles and/or glass jars. | 11. Reciclo o reutilizo las botellas de vidrio y/o frascos de vidrio. | 11. Отправляю в переработку и повторно использую стеклянную тару. |

| 12. I dispose of empty cans in the trash. | 12. Boto latas a la basura. | 12. Выбрасываю алюминиевые банки в мусор. |

| 13. I throw away cardboard packaging or wrapping. | 13. Boto a la basura los paquetes o embalajes de cartón. | 13. Выбрасываю в мусор картон/упаковочные материалы. |

| 14. I buy drinks or beer in returnable containers. | 14. Compro bebidas o cervezas en envases retornables. | 14. Покупаю напитки в многоразовой таре. |

| 15. I try to make my family and/or friends more environmentally friendly. | 15. He tratado que mis familiares y/o amigos sean más amigables con el medio ambiente. | 15. Стараюсь улучшить отношение родственников/друзей к окружающей среде. |

| 16. I recycle or reuse plastic bottles and/or plastic containers. | 16. Reciclo o reutilizo las botellas de plástico y/o frascos de plástico. | 16. Отправляю в переработку и повторно использую пластиковую тару. |

| 17. I turn down the heat when I leave my apartment/house for more than 1 h. | 17. Apago la calefacción cuando salgo de mi casa por más de 1 hora. | 17. Выключаю отопление, уходя из дома больше, чем на 1 час. |

| 18. I buy seasonal produce. | 18. Priorizo frutas y verduras de temporada. | 18. Предпочитаю покупать только сезонные фрукты/овощи. |

| 19. I take baths instead of showers. | 19. Me doy baños de tina, en vez de ducharme. | 19. Вместо душа предпочитаю принимать ванну. |

| 20. I buy organic products. | 20. Al realizar compras, compro productos orgánicos. | 20. Делая покупки, выбираю экологически чистые продукты. |

| 21. I use wood for heating. | 21. Uso calefacción a leña. | 21. Отапливаю дом дровами/углем. |

| 22. I reuse my shopping bags. | 22. Reutilizo las bolsas de la compra. | 22. Пользуюсь многоразовыми сумками для покупок. |

| 23. In the winter, I keep the heat on so that I do not have to wear a sweater. | 23. En invierno, pongo la calefacción tan alta que no tengo que usar sweater/polar. | 23. Зимой включаю отопление на такую температуру, чтобы не приходилось одевать свитер или кофту. |

| 24. I use the clothes dryer year-round. | 24. Utilizo secadora de ropa todo el año. | 24. Пользуюсь сушилкой для белья круглый год. |

| 25. When I brush my teeth, I keep the faucet on. | 25. Mientras cepillo mis dientes, mantengo la llave del agua abierta. | 25. Не выключаю воду, когда чищу зубы. |

| 26. I make compost with my organic waste (food scraps, fruit and vegetable waste), then I use it to fertilize plants. | 26. Hago compost con mis desechos orgánicos, para luego usarlo como abono para las plantas. | 26. Компостирую органические отходы, превращая их в органические удобрения. |

| 27. I am a member of an environmental organization. | 27. Soy miembro de una organización ambiental. | 27. Состою в организации по защите окружающей среды. |

| 28. I change my used towels every day. | 28. Cambio las toallas usadas cada día. | 28. Ежедневно меняю использованные полотенца. |

| 29. For long trips (more than 500 km) around the country, I prefer an airplane to a car and/or bus. | 29. Priorizo avión sobre el auto y/o bus para viajes largos (más de 500 kilómetros) dentro del país. | 29. Поездки по стране более чем на 500 км совершаю на самолете. |

| 30. After a picnic, I leave the place as clean as it was originally. | 30. Después de un picnic, dejo el lugar tan limpio como lo encontré. | 30. На пикнике стараюсь не оставлять за собой никакого мусора. |

| 31. I bought solar panels to produce energy. | 31. He comprado paneles solares para producir energía. | 31. У меня есть солнечные батареи для производства электроэнергии. |

| 32. I produce my own organic food (fruits, vegetables, honey, etc.). | 32. Produzco mis propios productos orgánicos (frutas y/o verduras y/o miel, etc.). | 32. Произвожу/выращиваю собственные органические продукты (фрукты/овощи, мед, молоко, сыр и т.д.). |

| 33. I dispose of used batteries in the garbage. | 33. Boto las pilas gastadas a la basura. | 33. Выбрасываю использованные батарейки в мусор. |

| 34. I boycott companies with an environmentally unfriendly background. | 34. Boicoteo compañías que tienen un historial antiecológico. | 34. Бойкотирую компании с плохой репутацией в области охраны окружающей среды. |

| 35. When I go to work or school, I usually carpool with one or more people. | 35. Comparto mi auto con una o más personas cuando voy al trabajo o a mi lugar de estudio. | 35. Добираюсь на работу/учебу на автомобиле совместно с другими людьми. |

| 36. I have a fuel-efficient car (more than 13 km per liter). | 36. Mi auto es de uso eficiente de combustible (más de 13 kilómetros por litro). | 36. Расход топлива у моего автомобиля на превышает 7,5 литров на 100 км. |

| 37. When I cook, I collect used oil in a bottle or container and then take it to a collection point. | 37. En la cocina, colecto el aceite usado en una botella o recipiente, para luego dejarlo en un punto de colecta. | 37. Использованное масло для жарки собираю и сдаю в приемный пункт. |

| 38. I make financial contributions to environmental organizations. | 38. Contribuyo económicamente a organizaciones ambientales. | 38. Делаю денежные взносы в организации по защите окружающей среды. |

| 39. I buy food in bulk (e.g., rice, noodles, nuts, beans, etc.) using my own containers. | 39. Compro productos a granel (por ejemplo, arroz, fideos, nueces, porotos, etc.) usando mis propios envases. | 39. Покупаю продукты оптом (рис, лапшу, орехи, бобы и т.д.) и в собственную тару. |

| 40. I have taken environmental courses to become more informed. | 40. He tomado clases ambientales para estar más informado/a. | 40. Посещаю лекции по охране окружающей среды, чтобы всегда быть в курсе. |

| English Translation | Spanish Items | Russian Items |

|---|---|---|

| 51. I helped push a stranger’s broken-down car. | 51. Empujo un auto en pana, perteneciente a una persona desconocida. | 51. Помогаю незнакомым завести машину с толкача. |

| 52. I gave directions to a stranger. | 52. Explico a una persona desconocida cómo llegar a un lugar. | 52. По просьбе незнакомых показываю им дорогу. |

| 53. I changed money for a stranger. | 53. Cambio dinero a una persona desconocida. | 53. По просьбе незнакомых размениваю им деньги. |

| 54. I gave money to a charity or fundraising campaign to help someone. | 54. Dono dinero a una organización de beneficencia o a una campaña de colecta de dinero para ayudar a otros. | 54. Жертвую деньги на благотворительность. |

| 55. I gave money to a stranger who needed it (or asked me for it). | 55. Entrego dinero a una persona desconocida que lo necesita. | 55. По просьбе незнакомых выручаю их деньгами. |

| 56. I donated goods or clothes to charity. | 56. Dono alimentos o ropa como caridad. | 56. Жертвую пищу и одежду на благотворительность. |

| 57. I did volunteer work for a charity. | 57. Hago trabajos voluntarios como caridad. | 57. Состою волонтером в благотворительной организации. |

| 58. I donate blood. | 58. Dono sangre. | 58. Сдаю кровь. |

| 59. I helped carry other people’s things (bags, parcels, etc.). | 59. Ayudo a cargar cosas (maletas, bolsos, etc.) a una persona desconocida. | 59. Помогаю незнакомым донести вещи (чемоданы, сумки и т.д.). |

| 60. I held up the elevator and held the door open for a stranger. | 60. Detengo un ascensor y mantengo sus puertas abiertas para una persona desconocida. | 60. Останавливаю лифт и придерживаю двери для незнакомых. |

| 61. I let people get in line ahead of me (when driving a car or standing in line at the store). | 61. Le doy la preferencia a una persona desconocida (en una fila, manejando auto, etc.). | 61. Пропускаю вперед незнакомых (в очереди, на машине и т.п.). |

| 62. I gave a stranger a ride in my car. | 62. Llevo en mi auto a una persona desconocida. | 62. Подвожу незнакомых на своей машине. |

| 63. When I get extra change, I give it back to the cashier. | 63. Al recibir vuelto demás en una caja, le devuelvo el dinero extra al cajero. | 63. Возвращаю кассиру лишнюю сдачу. |

| 64. I bought a product at a telethon. | 64. Compro un producto adherido a la Teletón. | 64. Покупаю товары на благотворительной распродаже. |

| 65. I refuse the help of strangers. | 65. Rechazo la solicitud de ayuda de una persona desconocida. | 65. Отказываю в помощи незнакомым. |

| 66. I offered to help a disabled or elderly stranger across the street. | 66. Ayudo a una persona desconocida (por ejemplo, anciana) a cruzar la calle. | 66. Помогаю незнакомым (например, пожилой женщине) перейти через дорогу. |

| 67. I offered my seat on the bus or train to a stranger who was standing. | 67. Cedo mi asiento a una persona desconocida, en un bus o en el metro. | 67. Уступаю свое место в общественном транспорте незнакомым людям. |

| 68. I would comfort a stranger who was crying. | 68. Consuelo a una persona desconocida que estaba llorando. | 68. Стараюсь утешить даже незнакомого человека, если он плачет. |

| 69. I would help a stranger who had fallen on the street. | 69. Ayudo a una persona desconocida que se cayó en la calle. | 69. Помогаю незнакомому человеку, упавшему на улице. |

| 70. I would keep walking without listening if a stranger asked me anything. | 70. Sigo mi camino cuando una persona desconocida comienza a pedirme algo y no la escucho. | 70. Игнорирую просьбы ко мне со стороны незнакомых людей на улице. |

| English Translation | Spanish Items | Russian Items |

|---|---|---|

| C1. How close do you feel to the following? | C1. ¿Qué tan cercano te sientes con cada uno de los siguientes grupos? | C1. Испытываю наибольшую близость с: |

| C2. Do you ever say “we” to refer to the following? | C2. ¿Qué tan seguido usas la palabra “nosotros” para referirte a los siguientes grupos? | C2. Говорю «мы» в отношении: |

| C3. How much would you say you have in common with the following? | C3. ¿Cuánto dirías que tienes en común con los siguientes grupos? | C3. Много ли у вас общего с: |

| C4. To what extent do you consider the following to be “family”? | C4. ¿Hasta qué punto piensas de los siguientes grupos como “familia”? | C4. Можете ли вы назвать «семьей»: |

| C5. How much do you care about the following? | C5. ¿Cuánto te preocupas por los siguientes grupos? | C5. Заботитесь ли вы о: |

| C6. How upset do you think you would be if something bad happened to the following? | C6. ¿Qué tanto dirías que sientes molestia cuando cosas malas suceden a los siguientes grupos? | C6. Беспокоят ли вас проблемы: |

| C7. How much would you like to be the following? | C7. ¿Qué tanto quisieras ser…? | C7. Хотите ли вы быть: |

| C8. How much do you believe in the following? | C8. ¿Qué tanto crees en…? | C8. Насколько вы преданы: |

| C9. If the need arose, how much would you like to help the following? | C9. En el caso de que surja la necesidad ¿Qué tanto quisieras ayudar a los siguientes grupos? | C9. Насколько вы готовы оказать помощь: |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. S23 | 2.38 | 1.17 | |||||||

| 2. S47 | 4.03 | 0.98 | 0.27 *** | ||||||

| [0.21, 0.33] | |||||||||

| 3. S71 | 3.53 | 1.13 | 0.23 *** | 0.49 *** | |||||

| [0.16, 0.29] | [0.44, 0.54] | ||||||||

| 4. S95R | 3.65 | 1.10 | 0.36 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.14 *** | ||||

| [0.30, 0.42] | [0.10, 0.23] | [0.08, 0.21] | |||||||

| 5. CH | 4.04 | 0.22 | 0.11 ** | 0.30 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.09 ** | |||

| [0.04, 0.18] | [0.24, 0.36] | [0.19, 0.31] | [0.03, 0.16] | ||||||

| 6. CN | 3.61 | 0.27 | 0.16 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.05 | 0.34 *** | ||

| [0.09, 0.23] | [0.15, 0.28] | [0.13, 0.26] | [−0.02, 0.12] | [0.28, 0.40] | |||||

| 7. Altruistic | −0.74 | 1.40 | 0.11 ** | 0.08 * | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 *** | 0.18 *** | |

| [0.05, 0.18] | [0.01, 0.15] | [−0.07, 0.07] | [−0.06, 0.07] | [0.19, 0.32] | [0.11, 0.24] | ||||

| 8. Ecological | −0.03 | 0.90 | 0.14 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.10 ** | 0.05 | 0.50 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.35 *** |

| [0.08, 0.21] | [0.08, 0.21] | [0.03, 0.16] | [−0.02, 0.12] | [0.45, 0.55] | [0.12, 0.25] | [0.29, 0.41] |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. S23 | 3.11 | 1.20 | |||||||

| 2. S47 | 3.94 | 1.03 | 0.24 *** | ||||||

| [0.15, 0.33] | |||||||||

| 3. S71 | 3.91 | 1.03 | 0.24 *** | 0.40 *** | |||||

| [0.15, 0.33] | [0.32, 0.48] | ||||||||

| 4. S95R | 3.59 | 1.07 | 0.30 *** | 0.14 ** | 0.17 *** | ||||

| [0.20, 0.38] | [0.04, 0.23] | [0.08, 0.27] | |||||||

| 5. CH | 3.35 | 0.41 | 0.22 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.16 ** | 0.06 | |||

| [0.12, 0.31] | [0.21, 0.39] | [0.06, 0.26] | [−0.04, 0.16] | ||||||

| 6. CN | 3.83 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.36 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.08 | 0.50 *** | ||

| [−0.01, 0.19] | [0.27, 0.44] | [0.15, 0.33] | [−0.02, 0.17] | [0.42, 0.57] | |||||

| 7. Altruistic | −0.46 | 1.28 | 0.08 | 0.31 *** | 0.11 * | 0.19 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.28 *** | |

| [−0.02, 0.18] | [0.21, 0.39] | [0.01, 0.20] | [0.10, 0.29] | [0.16, 0.35] | [0.19, 0.37] | ||||

| 8. Ecological | 0.23 | 0.95 | 0.14 ** | 0.21 *** | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.19 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.24 *** |

| [0.05, 0.24] | [0.11, 0.30] | [−0.06, 0.14] | [−0.08, 0.12] | [0.09, 0.28] | [0.28, 0.45] | [0.15, 0.33] |

References

- Eisenberg, N.; Shell, R. Prosocial Moral Judgment and Behavior in Children: The Mediating Role of Cost. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1986, 12, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; VanSchyndel, S.K.; Spinrad, T.L. Prosocial Motivation: Inferences from an Opaque Body of Work. Child Dev. 2016, 87, 1668–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batson, C.D.; Powell, A.A. Altruism and prosocial behavior. In Handbook of Psychology: Personality and Social Psychology; Millon, T., Lerner, M.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; Volume 5, pp. 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunfield, K.A. A construct divided: Prosocial behavior as helping, sharing, and comforting subtypes. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masson, T.; Otto, S. Explaining the difference between the predictive power of value orientations and self-determined motivation for proenvironmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 73, 101555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Otto, S.; Schuler, J. Prosocial propensity bias in experimental research on helping behavior: The proposition of a discomforting hypothesis. Compr. Psychol. 2015, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Byrka, K. Environmentalism as a trait: Gauging people’s prosocial personality in terms of environmental engagement. Int. J. Phychol. 2011, 46, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P.; Zabel, S.; Diaz-Siefer, P.; Burnham, E.; Navarro-Villarroel, C.; Neaman, A. The prosocial origin of sustainable behavior: A case study in the ecological domain. Glob. Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2021, 69, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neaman, A.; Otto, S.; Vinokur, E. Toward an integrated approach to environmental and prosocial education. Sustainability 2018, 10, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Corral-Verdugo, V.; Fraijo-Sing, B.; Durón-Ramos, M.F. Assessing sustainable behavior and its correlates: A measure of pro-ecological, frugal, altruistic and equitable actions. Sustainability 2013, 5, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schneider, F.; Klay, A.; Zimmermann, A.B.; Buser, T.; Ingalls, M.; Messerli, P. How can science support the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development? Four tasks to tackle the normative dimension of sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1593–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Fabio, A.; Rosen, M.A. Opening the black box of psychological processes in the science of sustainable development: A new frontier. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2018, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McFarland, S.; Webb, M.; Brown, D. All humanity is my ingroup: A measure and studies of identification with all humanity. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 830–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Price, J.; Leviston, Z. My country or my planet? Exploring the influence of multiple place attachments and ideological beliefs upon climate change attitudes and opinions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 30, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renger, D.; Reese, G. From equality-based respect to environmental activism: Antecedents and consequences of global identity. Polit. Psychol. 2017, 38, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.; Dietz, T. The value basis of environmental concern. J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredo, M.J.; Bruskotter, J.T.; Teel, T.L.; Fulton, D.; Schwartz, S.H.; Arlinghaus, R.; Oishi, S.; Uskul, A.K.; Redford, K.; Kitayama, S.; et al. Why social values cannot be changed for the sake of conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Shriver, C.; Tabanico, J.J.; Khazian, A.M. Implicit connections with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schultz, P.W.; Gouveia, V.V.; Cameron, L.D.; Tankha, G.; Schmuck, P.; Franěk, M. Values and their relationship to environmental concern and conservation behavior. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2005, 36, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Ashton, M.C. Psychometric Properties of the HEXACO-100. Assessment 2018, 25, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, M.C.; Lee, K. Empirical, Theoretical, and Practical Advantages of the HEXACO Model of Personality Structure. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 11, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Brown, S.L.; Lewis, B.P.; Luce, C.; Neuberg, S.L. Reinterpreting the empathy–altruism relationship: When one into one equals oneness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Batson, J.G.; Slingsby, J.K.; Harrell, K.L.; Peekna, H.M.; Todd, R.M. Empathic joy and the empathy-altruism hypothesis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Adger, W.N.; Devine-Wright, P.; Anderies, J.M.; Barr, S.; Bousquet, F.; Butler, C.; Evans, L.; Marshall, N.; Quinn, T. Empathy, place and identity interactions for sustainability. Glob. Environ. Chang.-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2019, 56, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M.R. Goal-directed conservation behavior: The specific composition of a general performance. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 1531–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, J.P.; Chrisjohn, R.D.; Fekken, G.C. The altruistic personality and the self-report altruism scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1981, 2, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Otto, S.; Neaman, A.; Richards, B.; Marió, A. Explaining the ambiguous relations between income, environmental knowledge, and environmentally significant behavior. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2016, 29, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.D.; Linacre, J.M.; Gustafson, J.E.; Martin-Lof, P. Reasonable mean-square fit values. Rasch Meas. Trans. 1994, 8, 370–371. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, S.; Kröhne, U.; Richter, D. The dominance of introspective measures and what this implies: The example of environmental attitude. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Frick, J.; Stoll-Kleemann, S. Zur Angemessenheit selbstberichteten Verhaltens: Eine Validitätsuntersuchung der Skala Allgemeinen Ökologischen Verhaltens [Accuracy of self-reports: Validating the general ecological behavior scale]. Diagnostica 2001, 47, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, A.; Kaiser, F.G.; Roczen, N. One for all? Connectedness to nature, inclusion of nature, environmental identity, and implicit association with nature. Eur. Psychol. 2011, 16, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.; Abrahamse, W. Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batson, C.D. Prosocial motivation: Is it ever truly altruistic? In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1987; pp. 65–122. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan, A. Understanding empathy. In Empathy: Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives; Coplan, A., Goldie, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cuff, B.M.P.; Brown, S.J.; Taylor, L.; Howat, D.J. Empathy: A Review of the Concept. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D. The Altruism Question: Toward a Social Psychological Answer; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, C.D. Altruism in Humans; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. 328. [Google Scholar]

- Decety, J.; Bartal, I.B.; Uzefovsky, F.; Knafo-Noam, A. Empathy as a driver of prosocial behaviour: Highly conserved neurobehavioural mechanisms across species. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roberts, W.; Strayer, J.; Denham, S. Empathy, Anger, Guilt: Emotions and Prosocial Behaviour. Can. J. Behav. Sci.-Rev. Can. Des Sci. Du Comport. 2014, 46, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telle, N.T.; Pfister, H.R. Not Only the Miserable Receive Help: Empathy Promotes Prosocial Behaviour Toward the Happy. Curr. Psychol. 2012, 31, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Keller, J. Shopping for Clothes and Sensitivity to the Suffering of Others: The Role of Compassion and Values in Sustainable Fashion Consumption. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 1119–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Sassenrath, C.; Schindler, S. Feelings for the Suffering of Others and the Environment: Compassion Fosters Proenvironmental Tendencies. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 929–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Siefer, P.; Neaman, A.; Salgado, E.; Celis-Diez, J.L.; Otto, S. Human-environment system knowledge: A correlate of pro-environmental behavior. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15510–15526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neaman, A.; Diaz-Siefer, P.; Burnham, E.; Castro, M.; Zabel, S.; Dovletyarova, E.A.; Navarro-Villarroel, C.; Otto, S. Catholic religious identity, prosocial and pro-environmental behaviors, and connectedness to nature in Chile. Gaia-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2021, 30, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensini, P.; Horn, E.; Caltabiano, N.J. An exploration of the relationships between adults’ childhood and current nature exposure and their mental well-being. Child. Youth Environ. 2016, 26, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-D’alessandro, A. The second side of education: Prosocial development. In Handbook of Prosocial Education; Brown, P.M., Corrigan, M.W., Higgins-D’Alessandro, A., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Villarroel, C. Young Students’ Attitudes toward Languages; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stapp, W.B.; Havlick, S.; Bennett, D.; Bryan, W., Jr.; Fulton, J.; MacGregor, J.; Nowak, P.; Swan, J.; Wall, R. The concept of environmental education. J. Environ. Educ. 1969, 1, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koger, S.M. Psychological and behavioral aspects of sustainability. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3006–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P. Nature-based environmental education of children: Environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefländer, A.K. Effectiveness of environmental education on water: Connectedness to nature, environmental attitudes and environmental knowledge. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bixler, R.D.; Joseph, S.L.; Searles, V.M. Volunteers as products of a zoo conservation education program. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 45, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, E.; Tabernero, C.; García, R.; Luque, B. The interactive effect of pro-environmental disciplinary concentration under cooperation versus competition contexts. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedefalk, M.; Almqvist, J.; Ostman, L. Education for sustainable development in early childhood education: A review of the research literature. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; O’Brien, M.U. Social and emotional learning and prosocial education: Theory, research and programs. In Handbook of Prosocial Education; Brown, P.M., Corrigan, M.W., Higgins-D’Alessandro, A., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 311–345. [Google Scholar]

- Vinokur, E. Reimagining European Citizenship: Europe’s Future Viewed from a Cosmopolitan Prism. In Cosmopolitanism: Educational, Philosophical and Historical Perspectives; Papastephanou, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Vinokur, E. Cosmopolitan Education in Local Settings: Toward a New Civics Education for the 21st Century. Policy Futures Educ. 2018, 16, 964–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Human Affairs. Global Humanitarian Overview 2021. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/GHO2021_EN.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2022).

| Variable | Russian Sample | Spanish Sample |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Mean ± SD | 31.2 ± 13.7 | 33.5 ± 13.2 |

| Range | 16–80 | 12–80 |

| Gender | ||

| Female (%) | 71 | 59 |

| Male (%) | 28 | 37 |

| Prefer not to specify (%) | 1 | 4 |

| Family income | ||

| We are perfectly comfortable with our income (%) | 1 | 9 |

| Our income is quite sufficient (%) | 8 | 24 |

| We can manage on our income (%) | 63 | 48 |

| It is pretty hard to live on our income (%) | 21 | 13 |

| It is extremely tough to live on our income (%) | 7 | 6 |

| Educational level | ||

| Incomplete high school (%) | 1 | 14 |

| High school (%) | 5 | 27 |

| Technical/vocational or 2-year degree (%) | 3 | 23 |

| University degree or undergraduate student (%) | 52 | 29 |

| Postgraduate (%) | 39 | 7 |

| Nationality | ||

| Russia (%) | 89 | - |

| Kazakhstan (%) | 2 | - |

| Chile (%) | - | 50 |

| Mexico (%) | - | 10 |

| Guatemala (%) | - | 6 |

| Other * (%) | 9 | 34 |

| Scale | Mean ± SD | Range | Reliability | Items with 1.2 < MS ≤ 1.3 | Items with MS > 1.3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russian sample | |||||

| Empathy | 3.40 ± 0.74 | 1.00–5.00 | 0.60 | N/A | N/A |

| Connection to nature | 3.61 ± 0.78 | 1.00–5.00 | 0.88 | N/A | N/A |

| Connection to humans | 4.04 ± 0.65 | 1.00–5.00 | 0.86 | N/A | N/A |

| Ecological behavior | −0.03 ± 0.90 | −2.67–2.72 | 0.79 | 4 | 0 |

| Altruistic behavior | −0.74 ± 1.40 | −4.61–3.62 | 0.78 | 2 | 0 |

| Sustainable behavior | −0.24 ± 0.83 | −2.71–2.88 | 0.84 | 4 | 0 |

| Spanish sample | |||||

| Empathy | 3.63 ± 0.72 | 1.25–5.00 | 0.57 | N/A | N/A |

| Connection to nature | 3.83 ± 0.76 | 1.00–5.00 | 0.88 | N/A | N/A |

| Connection to humans | 3.35 ± 0.82 | 1.00–5.00 | 0.89 | N/A | N/A |

| Ecological behavior | 0.23 ± 0.95 | −3.73–3.48 | 0.81 | 2 | 0 |

| Altruistic behavior | −0.46 ± 1.28 | −4.30–3.49 | 0.76 | 0 | 1 |

| Sustainable behavior | 0.00 ± 0.79 | −3.62–2.17 | 0.83 | 0 | 0 |

| Variable | Pearson Correlations with Connection to Nature | |

|---|---|---|

| Study of [8], [34] scale | Present study, [13] modified scale | |

| Altruistic behavior | 0.36 *** | 0.28 ** |

| Ecological behavior | 0.55 *** | 0.37 ** |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russian sample | ||||

| 1. Empathy | ||||

| 2. Connection to nature | 0.23 *** | |||

| [0.16, 0.29] | ||||

| 3. Connection to humans | 0.27 *** | 0.34 *** | ||

| [0.21, 0.33] | [0.28, 0.40] | |||

| 4. Altruistic behavior | 0.07 * | 0.25 *** | 0.18 *** | |

| [0.01, 0.14] | [0.19, 0.32] | [0.11, 0.24] | ||

| 5. Ecological behavior | 0.16 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.35 *** |

| [0.09, 0.23] | [0.45, 0.55] | [0.12, 0.25] | [0.29, 0.41] | |

| Spanish sample | ||||

| 1. Empathy | ||||

| 2. Connection to nature | 0.28 *** | |||

| [0.18, 0.37] | ||||

| 3. Connection to humans | 0.28 *** | 0.50 *** | ||

| [0.19, 0.37] | [0.42, 0.57] | |||

| 4. Altruistic behavior | 0.26 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.26 *** | |

| [0.16, 0.35] | [0.19, 0.37] | [0.16, 0.35] | ||

| 5. Ecological behavior | 0.15 ** | 0.37 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.24 *** |

| [0.05, 0.25] | [0.28, 0.45] | [0.09, 0.28] | [0.15, 0.33] | |

| Standardized Regression Coefficients | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X → M | M → Y | Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | |

| Honesty–humility → Connection to nature → Ecological behavior | |||||

| 0.12 * | 0.48 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.06 * | −0.00, 0.12 |

| Honesty–humility → Connection to nature → Altruistic behavior | |||||

| 0.12 * | 0.29 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.04 * | −0.00, 0.08 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neaman, A.; Pensini, P.; Zabel, S.; Otto, S.; Ermakov, D.S.; Dovletyarova, E.A.; Burnham, E.; Castro, M.; Navarro-Villarroel, C. The Prosocial Driver of Ecological Behavior: The Need for an Integrated Approach to Prosocial and Environmental Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074202

Neaman A, Pensini P, Zabel S, Otto S, Ermakov DS, Dovletyarova EA, Burnham E, Castro M, Navarro-Villarroel C. The Prosocial Driver of Ecological Behavior: The Need for an Integrated Approach to Prosocial and Environmental Education. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):4202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074202

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeaman, Alexander, Pamela Pensini, Sarah Zabel, Siegmar Otto, Dmitry S. Ermakov, Elvira A. Dovletyarova, Elliot Burnham, Mónica Castro, and Claudia Navarro-Villarroel. 2022. "The Prosocial Driver of Ecological Behavior: The Need for an Integrated Approach to Prosocial and Environmental Education" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 4202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074202

APA StyleNeaman, A., Pensini, P., Zabel, S., Otto, S., Ermakov, D. S., Dovletyarova, E. A., Burnham, E., Castro, M., & Navarro-Villarroel, C. (2022). The Prosocial Driver of Ecological Behavior: The Need for an Integrated Approach to Prosocial and Environmental Education. Sustainability, 14(7), 4202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074202