Strengthening of Community Tourism Enterprises as a Means of Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: A Case Study of Community Tourism Development in Chimborazo

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Contextualization of Community Tourism in Chimborazo (Ecuador)

2.1. Community Tourism

- It is a type of tourism managed by and for the local community [26,27] as a way of reducing the negative consequences of tourism. Cañada [28] corroborates this statement, since he understands that this type of tourism is based on a tourism management model in which the local population of a given territory, generally a disadvantaged one, plays a leading role in the control of its design, execution, management, and distribution of benefits derived from the tourism activity [29,30,31]. Several studies address the issue of community participation and control [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39].

- The participation of the local population (local stakeholders and tourism providers) is one of the pillars on which it is based [40], enabling the empowerment of local communities [38]. Many researchers agree on the need for community involvement in tourism [41,42]. This empowerment is achieved according, to Shafieisabet and Haratifard [43] (p. 76), “through training [44], informing them [45] about available environmental resources [46] and promoting their personal and social characteristics and flexibility in spatial area [47] in order to create a clean and attractive environment for tourists [48] and improve their quality of life by increasing tourism income, which can ensure sustainable rural development in rural settlements along the tourism route and destination [45]”.

- It is generally a small-scale type of tourism (Asker et al., 2010) that improves indicators related to the quality of life of the local population involved in tourism [49].

- The benefits derived from its development are manifold:

2.2. Plurinational Federation of Community Tourism in Ecuador

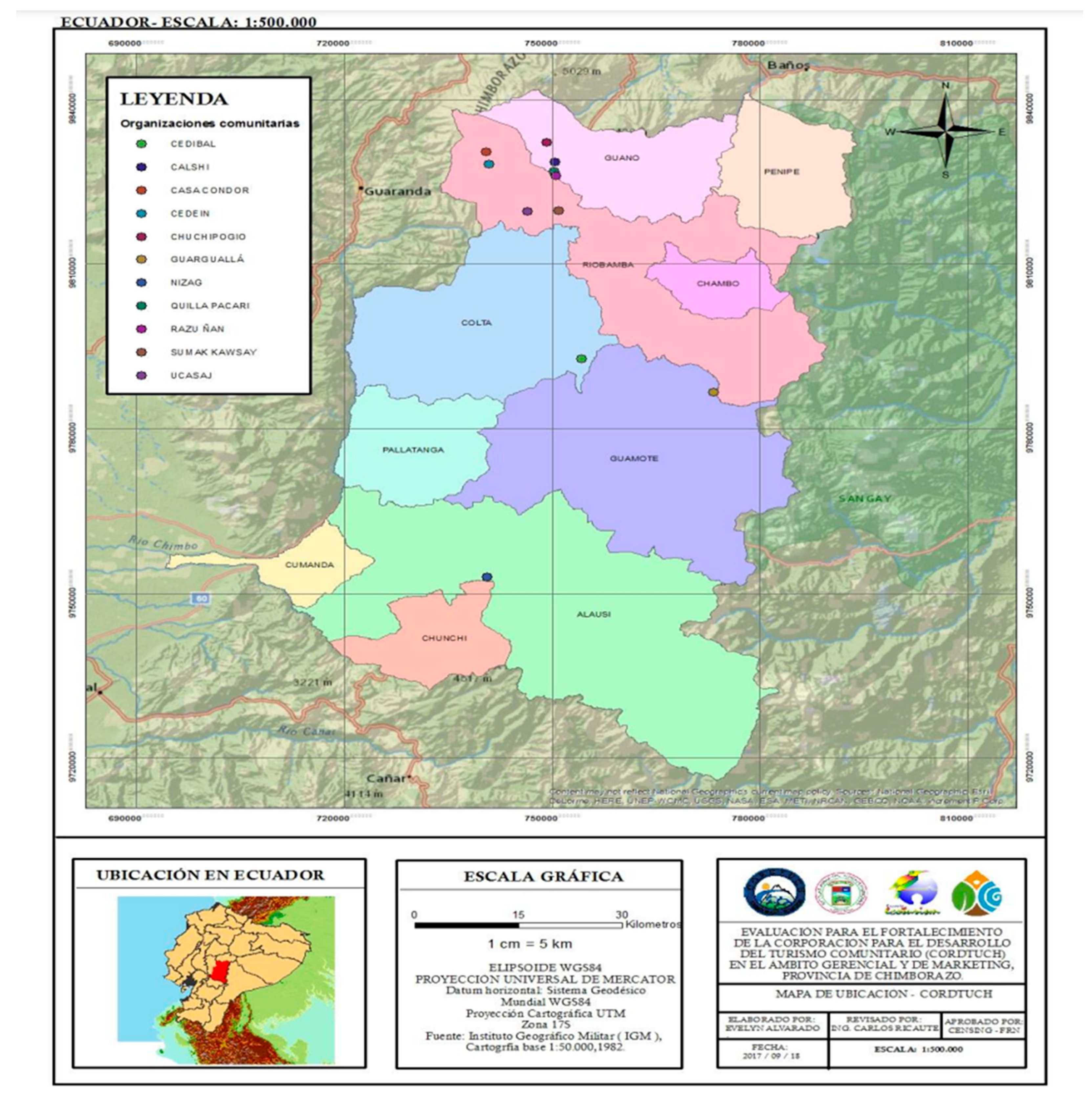

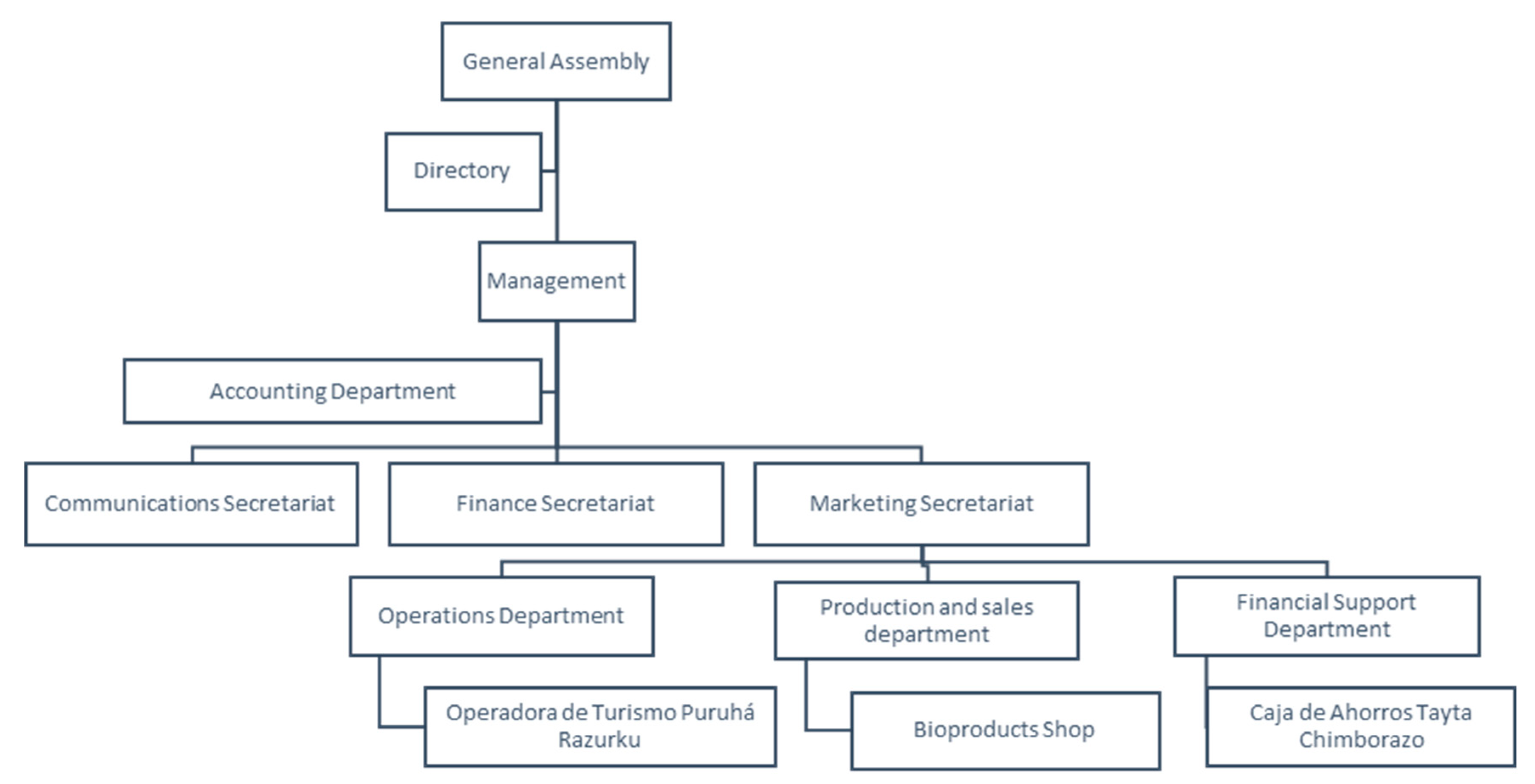

2.3. Corporation for the Development of Community Tourism (CORDTUCH)

3. Methodology

4. Overview of Community Tourism linked to CORDTUCH

4.1. Social Dimension

4.2. Environmental Dimension

- Forestation and reforestation: action implemented in the 11 CTOs. It corresponds to the implementation of small forest nurseries of native species, transplanted to eroded and deforested areas and even to family plots to be used as live fences for the protection of crops. This activity has also generated extra income from the commercialization of species.

- Management of páramo, natural areas, and micro-watersheds: implementation of strategies for the management of páramo as a source of water and reduction of the livestock load corresponding to cattle and sheep, which was replaced by camelids (llama and alpaca). It is also responsible for formulating regulations to control the burning of grasslands and the fencing off of water sources. These actions were implemented in Guarguallá, UCASAJ, Casa Cóndor, CEDEIN, and Chuquipogio, which are all areas of influence of Sangay National Park and RPFCH.

- Recovery of water sources: This is linked to the recovery of hectares of cushion and grassy páramo ecosystems, which are established as sources of water reserves, for which work has been done with the insertion of camelids and the declaration of communal conservation areas.

- Organic production: incorporation of ancestral practices to strengthen agriculture, allowing the generation of agroecological gardens, mainly in UCASAJ, CEDEIN, Balda Lupaxi, Casa Cóndor, and Razu Ñan, an activity that is currently linked to the tourist offer of the communities.

- Waste management: implementation of recycling processes and composting processes to obtain organic fertilizer, in which the local population has been involved, especially children in Razu Ñan and Balda Lupaxi. This action has made it possible to improve the condition of the cultural landscape.

4.3. Organizational Dimension

- Operadora de Turismo Puruhá Razurku: Created in 2006, this company’s purpose is the commercialization of tourism products generated by the 11 OTCs [91]. The first package that was sold had a cost of USD 70 and left a net profit of USD 15; the rest was given to the community that hosted the tourist [72]. Within the work structure, it is made up of four employees [92].

4.4. Cultural Dimension

4.5. Economic Dimension

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNWTO. UNWTO World Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex, December 2020; UNWTO World Tourism Barometer: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Volume 18, pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONU. UNWTO: International Tourism Registered in 2003 the Greatest Setback in History. UN News Noticias ONU. 2004. Available online: https://news.un.org/es/story/2004/01/1028571 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- UNWTO. 2020: The Worst Year in the History of Tourism, with One Billion Fewer International Arrivals; UNWTO World Tourism Barometer: Madrid, Spain, 2021; Available online: https://thediplomatinspain.com/en/2021/01/2020-worst-year-in-tourism-history-with-1-billion-fewer-international-arrivals/ (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- UNWTO. 24a Reunión de la Asamblea General de la OMT. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/es/24-reunion-de-la-asamblea-general-de-la-omt/sesion-tematica (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Nexotur. The UNWTO Looks towards a Green and Inclusive Tourism. Nexotur. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/unwto-points-tourism-towards-a-greener-inclusive-future-at-general-assembly (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Ministry of Tourism of Ecuador. Turismo Rural Será Clave Para la Reactivación del Sector Post COVID-19/Rural Tourism Will Be Key to the Reactivation of the Post-COVID-19 Sector. 2020. Available online: https://www.turismo.gob.ec/turismo-rural-sera-clave-para-la-reactivacion-del-sector-post-covid-19/ (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Bravo, E.F.O.; Sánchez, L.D.R.F.; Belema, L.A.A.; Viteri, X.A.S. Gestión del turismo comunitario en el sector indígena de la provincia de chimborazo caso: La Moya. Explor. Digit. 2020, 4, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Cumbajín, C.; Yánez-Segovia, S.; Hernández-Benalcázar, H.; Méndez-Játiva, J.F.; Valdiviezo-Leroux, W.; Tafur, V. La situación del turismo comunitario en Ecuador. Dominio Cienc. 2018, 4, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FEPTCE. Guia de Turismo Comunitario del Ecuador; Imprenta Mariscal: Quito, Ecuador, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Erazo, C.P.; del Río-Rama, M.D.L.C.; Noboa-Viñan, P.; Álvarez-García, J. Community-based tourism in Ecuador: Community ventures of the provincial and cantonal networks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redclift, M.; Springett, D. Routledge International Handbook of Sustainable Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lalayan, A. Community Based Tourism in Armenia: Planning for Sustainable Deveopment. Ph.D. Thesis, Asia Pacific University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fayos-Sola, E. Knowledge Management in Tourism: Policy and Governance Applications; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R.; Telfer, D.J. Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2015; Volume 63. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, I.; Williams, A.M.; Hall, C.M. Tourism innovation policy: Implementation and outcomes. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hutchins, F. Footprints in the forest: Ecotourism and altered meanings in Ecuador’s upper Amazon. J. Lat. Am. Caribb. Anthropol. 2007, 12, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, A.; Clifton, J. Assessing tourism’s impacts using local communities’ attitudes toward the environment. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2004, 76, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanilla, E. Turismo comunitario en América Latina, un concepto en construcción. Siembra 2018, 5, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanilla, E.; Garrido, C. El Turismo Comunitario en el Ecuador: Evolución, Problemática Y Desafios; Velásquez, F., Ed.; UIDE: Quito, Ecuador, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rodas, M.; Ullauri, N.; Sanmartín, I. El turismo comunitario en el Ecuador: Una revisión de la literatura. RICIT Rev. Tur. Desarro. Y Buen Vivir 2015, 9, 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez, D.; Ochoa, B. Turismo Rural. Instituto Tecnológico de Sonora. 2015. Available online: www.itson.mx (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Häusler, N.; Strasdas, W. Training Manual for Community-Based Tourism. Addendum to The Ecotourism Training Manual for Protected Area Management; InWEnt—Capacity Building International: Bonn, Germany, 2003; Available online: https://cupdf.com/document/ecotourismtrainingmanual-cbt.html?page=1 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Netherlands Development Organization (SNV). Asia Pro-Poor Sustainable Tourism Network. A Toolkit for Monitoring and Managing Community-Based Tourism; SNV Asia Pro-Poor Sustainable Tourism Network and Griffith University: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Sánchez Cañizares, S.M. Turismo comunitario y generación de riqueza en países en vías de desarrollo. Un estudio de caso en el Salvador. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2009, 30, 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Asker, S.; Boronyak, L.; Carrard, N.; Paddon, M. Effective Community Based Tourism: A Good Practice Manual; CRC for Sustainable Tourism Pty Ltd.: Parkwood, QLD, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kavita, E.; Saarinen, J. Tourism and rural community development in Namibia: Policy issues review. Fenn.-Int. J. Geogr. 2015, 194, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheyvens, R. Promoting women’s empowerment through involvement in ecotourism: Experiences from the third world. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañada, E. Turismo en Centroamérica. Un Diagnóstico Para el Debate; Editorial Enlace: Managua, Nicaragua, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sutawa, G.K. Issues on Bali tourism development and community empowerment to support sustainable tourism development. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2012, 4, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Breugel, L. Community-based tourism: Local participation and perceived impacts. Ph.D. Thesis, Radboud University Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecka, M.; Boley, B.B.; Strzelecka, C. Empowerment and resident support for tourism in rural Central and Eastern Europe (CEE): The case of Pomerania, Poland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, J.C. People on country, healthy landscapes and sustainable indigenous economic futures: The arnhem land case. Draw. Board Aust. Rev. Public Aff. 2003, 4, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zeppel, H. Indigenous Ecotourism: Sustainable Development and Management; CABI Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zeppel, H. Indigenous ecotourism: Conservation and resource rights. In Critical Issues in Ecotourism: Understanding a Complex Tourism Phenomenon; Higham, J.E.S., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 308–348. [Google Scholar]

- Colton, J.W. Indigenous tourism development in northern Canada: Beyond economic incentives. Can. J. Nativ. Stud. 2005, 1, 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Salole, M. Merging Two disparate worlds in rural Namibia: Joint venture tourism in torra conservancy. In Tourism and Indigenous Peoples: Issues and Implications; Butler, R., Hinch, T., Eds.; Elsevier: Burlington, Vermont, 2007; pp. 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Colton, J.W.; Whitney-Squire, K. Exploring the relationship between aboriginal tourism and community development. Leisure/Loisir 2010, 34, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dodds, R.; Graci, S. Sustainable tourism in island destinations. Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell, W.T. Taiwan aboriginal ecotourism: Tanayiku natural ecology park. Annals Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 876–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Introduction to Tourism in Australia: Impacts, Planning and Development; Addison, Wesley and Longman: Melbourne, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, A.L.; Beeton, R.J. Sustainable tourism or maintainable tourism: Managing resources for more than average outcomes. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 9, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J. The Evolution of Tourism Development Theory. In Tourism Development, Concepts and Issues; Sharpley, R., Telfer, D., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Clevendon, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 35–81. [Google Scholar]

- Shafieisabet, N.; Haratifard, S. Community-based tourism: An approach for sustainable rural development (Case study: Asara district, chalous road). J. Sustain. Rural Dev. 2019, 3, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, V.G.; Font, X. Community based tourism: Critical success factors. Int. Cent. Responsib. Tour. 2013, 27, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Muigua, K. Empowering the kenyan people through alternative dispute resolution mechanisms. In Proceedings of the CIArb Africa Region Centenary Conference, London, UK, 1–3 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.; Kim, S. Enhancing local community’s involvement and empowerment through practicing Cittaslow: Experiences from Goolwa. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conferenece on Tourism Research (4ICTR), Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 9–11 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, B.; Gusoy, D.; Wall, G. Residents’ support for red tourism in China: The moderating effect of central government. Annals Tour. Res. 2017, 64, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.H.; Lo, M.C.; Ramayah, T. Rural tourism sustainable management and destination marketing efforts: Key factors from communities’ perspective. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Ertuna, B.; Sasidharan, V. A referential methodology for education on sustainable tourism development. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5029–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Codespa, F. Programa RUTAS: La Apuesta por un Turismo Inclusivo en Latinoamérica. Metodología para el Fortalecimiento de Iniciativas de Turismo Rural Comunitario; CAF-Fundación CODESPA and Development Bank Of Latinamerica: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Available online: https://www.codespa.org/app/uploads/metodologia-para-el-fortalecimiento-de-iniciativas-de-turismo-rural-comunitario.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Waligo, V.M.; Clarke, J.; Hawkins, R. Implementing sustainable tourism: A multi-stakeholder involvement management framework. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muresan, I.C.; Oroian, C.F.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.H.; Porutiu, A.; Chiciudean, G.O.; Todea, A.; Lile, R. Local residents’ attitude toward sustainable rural tourism development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wall, G.; Mathieson, A. Tourism: Change, Impacts, and Opportunities; Pearson Education: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Manu, I.; Kuuder, C.J.W. Community-based ecotourism and livelihood enhancement in Sirigu, Ghana. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. Multinational Federation of Community Tourism in Ecuador (FEPTCE). Local Sustainable Development Solutions for People, Nature, and Resilient Communities; Equator Initiative Case Study Series: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- FEPTCE. Proyecto: Código de Operaciones de la Federación Plurinacional de Turismo Comunitario del Ecuador 2011/2013. 2010. Available online: https://es.scribd.com/document/313836878/Codigo-de-Operaciones-Feptce (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Carpentier, J. El turismo comunitario y sus nuevos actores: El caso de las petroleras en la Amazonia ecuatoriana. In Amazonía, Viajeros, Turistas y Poblaciones Indígenas; Valcuende del Rio, J.M., Ed.; Pasos: Quito, Ecuador, 2012; pp. 293–328. Available online: https://hal-univ-paris10.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01632040 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Tourism Law of Ecuador. Registro Oficial Suplemento No. 733, 27 de diciembre de 2002. Available online: https://www.turismo.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/LEY-DE-TURISMO.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- SENPLADES. Plan Nacional del Buen Vivir (PNBV) 2009–2013; SENPLADES: Quito, Ecuador, 2009; Available online: https://www.planificacion.gob.ec/plan-nacional-para-el-buen-vivir-2009-2013/ (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- SENPLADES. Plan Nacional para el Buen Vivir 2013–2017; SENPLADES: Quito, Ecuador, 2013. Available online: http://documentos.senplades.gob.ec/Plan Nacional Buen Vivir 2013-2017.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Loor, L.; Plaza, N.; Medina, Z. Turismo comunitario en Ecuador: Apuntes en tiempos de pandemia. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2021, 27, 265–277. [Google Scholar]

- SENPLADES. Transformación de la Matriz Productiva; SENPLADES: Quito, Ecuador, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Secretariat for Planning. Plan de Creación de Oportunidades 2021–2025. 2021. Available online: https://www.planificacion.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Plan-de-Creación-de-Oportunidades-2021-2025-Aprobado.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Ministry of Tourism of Ecuador. PLANDETUR 2020; Ministerio de Turismo: Quito, Ecuador, 2007.

- Ministry of Tourism of Ecuador. Proyecto Ecuador Potencia Turística 2015; Ministerio de Turismo: Quito, Ecuador, 2015. Available online: https://www.turismo.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Documento-Proyecto-Ecuador-Pote%0Ancia-Turística.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Ministry of Tourism of Ecuador. Plan Estratégico Institucional 2019–2021; Ministerio de Turismo: Quito, Ecuador, 2019.

- Ministry of Tourism of Ecuador. Plan Nacional de Turismo 2030; Ministerio de Turismo: Quito, Ecuador, 2019. Available online: https://www.turismo.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/PLAN-NACIONAL-DE-TURISMO-2030-v.-final-Registro-Oficial-sumillado-comprimido_compressed.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Ministry of Tourism of Ecuador. Catastro Turístico Nacional de Establecimientos; Ministerio de Turismo: Quito, Ecuador, 2021. Available online: https://servicios.turismo.gob.ec/portfolio/catastro-turistico-nacional (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Ochoa, W. Guía Básica de Estudio de Turismo Comunitario Y Solidario; FEPTCE: Quito, Ecuador, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Guamán, M.A. El Turismo Comunitario: Alcances, Limitaciones Y Propuesta de Desarrollo en la Provincia de Chimborazo; Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo: Quito, Ecuador, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Forestry and Conservation of Natural Areas and Wildlife Law of Ecuador. Ley No. 74. RO/64 de 24 de Agosto. 1981. Available online: https://www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/4033.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- CORDTUCH. Chimborazo Desde Adentro; CORDTUCH—Corporación para el Desarrollo de Turismo Comunitario de Chimborazo: Quito, Ecuador, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation for the Registration of Community Tourist Centres. 2006. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC066227/ (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Law on the Organization and Regime of Communes. 2004. Available online: https://www.gob.ec/regulaciones/ley-organizacion-regimen-comunas (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Barthol, R.; Sansolo, D.; Bursztyn, I. Turismo de Base Comunitária: Diversidade de Olhares E Experiências Brasileiras; Ministerio do Turismo, Ed.; Ministerio do Turismo: Brasilia, Brazil, 2009. Available online: http://www.each.usp.br/turismo/livros/turismo_de_base_comunitaria_bartholo_sansolo_bursztyn.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Acuerdo Ministerial 235. 2006; Ministerio de Ecuador. Available online: https://www.defensa.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2018/11/Acuerdo-Ministerial-Nro.-235-Delegaciones.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- CORDTUCH. Chimborazo Turismo Comunitario; CORDTUCH—Corporación para el Desarrollo de Turismo Comunitario de Chimborazo: Quito, Ecuador, 2019; Available online: https://issuu.com/cordtuch.org/docs/revista_chimborazo_desde_adentro2_05d78b620ee5b8 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Piray, M.; Tierra-Tierra, N.; Bautista, M.; Lasluisa, M.; Guamán, M.; Aymacaña, C.; Noboa, P.; Tenemasa, A. Sistematización de las Experiencias de Turismo Comunitario de la Provincia de Chimborazo. MKT: Descubre. Comercialización Investigación & Negocios, (3232-12): Riobamba, Ecuador, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Equator Initiative. Corporación para el Desarrollo de Turismo Comunitario de Chimborazo. 2020; Available online: https://www.equatorinitiative.org/2020/04/24/solution11244/ (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Araque, S.M. Diseño de un Sistema de Señalética Turística para las Operaciones de Turismo Comunitario; CORDTUCH: Riobamba, Ecuador, 2012; Available online: http://dspace.espoch.edu.ec/handle/123456789/1838 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Secretary of Human Rights; Directorio de Organizaciones Sociales. Sistemda Unificado de Información de las Organizaciones Sociales. 2002. Available online: https://sociedadcivil.gob.ec/nuevo_directorio (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Alvarado, E. Evaluación Para el Fortalecimiento de la Corporación Para el Desarrollo del Turismo Comunitario (CORDTUCH) en el Ámbito Gerencial Y de Marketing, Provincia de Chimborazo; CORDTUCH: Riobamba, Ecuador, 2008; Available online: http://dspace.espoch.edu.ec/handle/123456789/8400 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Pastor-Alfonso, M.J.; Espeso-Molinero, P. Capacitación turística en comunidades indígenas. Un caso de investigación acción participativa (IAP). El Periplo Sustentable Rev. Tur. Desarro. Compet. 2015, 29, 171. [Google Scholar]

- Skewes, J.C.; Guerra, D.E. The defense of maiquillahue bay: Knowledge, faith, and identity in an environmental conflict. Ethnology 2004, 43, 217–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. El impacto de la pandemia del COVID-19 en la investigación mundial. High. Educ. 2020, 104, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, A. La Cultura. Estrategias Conceptuales Para Entender la Identidad, la Diversidad, la Alteridad Y la Diferencia; Abya-Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, V. Community Cultural Revitalization Manual of Torres/ Manual de Revitalización Cultura Comunitaria; Comunicec: Quito, Ecuador, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- SNV. Guía de Buenas Prácticas de Turismo Sostenible para Comunidades de Latinoaméricana/Guide of Good Practices in Sustainable Tourism for Latin American Communities; SNV-Rainforest Alliance-Counterpart International: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Salazar, S.; Tierra-Tierra, N.; Lozano-Rodríguez, P.; Tayupanda-Pagalo, M. Turismo comunitario en los andes ecuatorianos. Estudio de caso: Legalización de las organizaciones filiales de la corporación para el desarrollo de turismo comunitario de chimborazo, provincia de Chimborazo, Ecuador. Polo Del Conoc. 2021, 6, 81–107. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón, M. Diseño de un Plan de Gestión y Educación Ambiental para Mejorar la Oferta Turística de los Once Centros de Turismo Comunitario Filiales a la Corporación para el Desarrollo de Turismo Comunitario de Chimborazo; CORDTUCH: Riobamba, Ecuador, 2012; Available online: http://dspace.espoch.edu.ec/handle/123456789/776 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Gómez, T. Elaboración del Plan de Capacitación Para el Fortalecimiento Organizativo de la Corporación Para el Desarrollo del Turismo Comunitario de Chimborazo; CORDTUCH: Riobamba, Ecuador, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Salazar, S.; Rodríguez, P.X.; Flores-Mancheno, A.C.; Gómez-Álvarez, T.A. Fortalecimiento organizativo de la Corporación para el Desarrollo de Turismo Comunitario de la provincia de Chimborazo, Ecuador. Dominio Cienc. 2021, 7, 802–821. [Google Scholar]

- ILO Convention, No. 169. 1989. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---americas/---ro-lima/documents/publication/wcms_445528.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Nagoya Protocol. Protocolo de Nagoya Sobre Acceso a Los Recursos Genéticos y Participación Justa y Equitativa en Los Beneficios Que Se Deriven de Su Utilización al Convenio Sobre la Diversidad Biológica; Secretaria del Convenio sobre la Diversidad Biológica Naciones Unidas, Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2011; Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/doc/protocol/nagoya-protocol-es.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Código Ingenios of Ecuador. Código Orgánico de la Economía Social de los Conocimientos, Creatividad e Innovación. 09 de 12. Asamblea Nacional de la Republica de Ecuador. Official Registration of 9 December 2016. Available online: https://www.asle.ec/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/ingenios-09-12-2016.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Castillo-Vizuete, D.; Miranda-Salazar, S.; Jara-Santillán, C.; Quevedo-Baez, L. Cartografía Patrimonial Y de Turismo Comunitario Provincia de Chimborazo; Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo: Chimborazo, Ecuador, 2018; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/38559849/Cartograf%C3%ADa_patrimonial_y_de_turismo_comunitario_provincia_de_Chimborazo (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Llanga, R. Análisis de la Situación Actual del Turismo Comunitario Articulado a Áreas Protegidas en la Provincia de Chimborazo; Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo: Chimborazo, Ecuador, 2017; Available online: http://dspace.espoch.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/8394/1/23T0651.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Travel Agencies Finder. Cordtuch—Turismo Comunitario de Chimborazo. 2022. Available online: https://www.travelagenciesfinder.com/EC/Riobamba/708786192592282/Cordtuch---Turismo-Comunitario-de-Chimborazo (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Community Tourism Operator “Puruhá Razurku”. 2022. Available online: https://www.fairtrips.com/hosts/puruha-razurku (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Viteri Gualinga, C. Visión indígena del desarrollo en la Amazonía. Polis Rev. Latinoam. 2002, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Graci, S. Putting community based tourism into practice: The case of the Cree Village Ecolodge in Moose Factory, Ontario. Téoros Rev. Rech. Tour. 2012, 31, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

| Rural Tourism (RT) | Community Tourism (CT) or Community-Based Tourism (CBT) |

|---|---|

| It takes place in locations of tourist interest that are a counterpoint to urban centers. As the definition is complex, it is necessary to establish what “rural” is. This will largely depend on the realities established by each territory. | It takes place within peoples or nationalities, as well as in spaces legally recognized as local communities, with strong ties of cultural identity between the members of the human group and the surrounding heritage. |

| Reduced number of service providers for tourists, but with a variety of products, in addition to being in harmony with the infrastructures of the area. | Limited tourism offer that depends on the organizational capacity of the community and that is restricted to the resources of the area, where the infrastructures are committed to the integration of designs with permaculture. |

| Optimum use of the natural and cultural resources of the area by integrating the precepts of sustainability through the local population´s knowledge. | Use of the cultural and natural heritage based on heritage processes led by the community members that consolidate a comprehensive sustainability process. |

| Vertical management model linked to a market economy that takes care of the individual interests of the participants in the tourism modality. It is focused on achieving maximum profitability. | Horizontal management model that takes into consideration the social vindication processes of historically neglected groups, putting community interests before individual ones. It focuses on obtaining profitability that will be redistributed equitably within the group. |

| Regional Network | Canton | Name of the Enterprise | Year of Creation | Number of Communities | Condition | Registration–CT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Tourism Network Sierra Centro “Kawsaymanta” | Alausí | Nizag Agro-Craft Center | 2001 | 1 | Active | No |

| Colta | Center for Indigenous Development (CEDEIN) | 1995 | 14 of Colta and Guamote | Active | No | |

| Colta | Balda Lupaxi Integral Development Center (CEDIBAL) | 2004 | 1 | Partially active | No | |

| Guamote | Guarguallá Craft and Community Tourism Center | 2008 | 2 | Active | No | |

| Guano | Calshi | 2004 | 1 | Active | No | |

| Guano | Chuquipogio | 2005 | 1 | Inactive | No | |

| Guano | Razu Ñan | 2003 | 1 | Active | No | |

| Riobamba | Casa Cóndor | 1997 | 1 | Active | Yes | |

| Riobamba | Union of Indigenous Peasants San Juan (UCASAJ) | 2002 | 11 | Partially active | No | |

| Riobamba | Sumak Kawsay—Royal Palace | 2006 | 1 | Active | Yes | |

| Riobamba | Quilla Pacari | 1998 | 1 | Active | Yes |

| Component | Problem | Nizag Agro-Craft Center | CEDEIN | CEDIBAL | Guarguallá Craft and Community Tourism Center | Calshi | Chuquipogio | Razu Ñan | Casa Cóndor | UCASAJ | Sumak Kawsay—Royal Palace | Quilla Pacari |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ground | Ground erosion | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Erosion from overgrazing | x | |||||||||||

| Advance of the agricultural frontier | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Garbage contamination of soils | x | x | ||||||||||

| Loss of vegetation cover in the páramos | x | |||||||||||

| Pollution of the wastelands | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Family land contamination | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Mining exploitation | x | |||||||||||

| Degradation of cultivated land | x | |||||||||||

| Water | River pollution | x | ||||||||||

| Unprotected waterholes | x | |||||||||||

| Unprotected micro-basins | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Air | Pollution generated by the decomposition of garbage | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Pollution due to the emission of gases due to the transit of land and heavy transport | x | x | ||||||||||

| Flora | Loss of native vegetation | x | x | |||||||||

| Eucalyptus monoculture | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Pine monoculture | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Loss of native vegetation | ||||||||||||

| Native forest felling | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Straw burning | x | |||||||||||

| Loss of grasslands | x | |||||||||||

| Reforestation with pines and eucalyptus | x | x | ||||||||||

| Fauna | Displacement of wildlife to surrounding areas | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Proliferation of domestic and sick animals | x | |||||||||||

| Decrease in the avifauna | x |

| Canton | Name of the Enterprise | Registration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Movable Property | Immovables | ||

| Alausí | Nizag Agro-Craft Center | 8 | 2 |

| Guano | Calshi | 11 | 3 |

| Guano | Razu Ñan | 11 | 1 |

| Riobamba | Casa Cóndor | 10 | 1 |

| Riobamba | UCASAJ | 13 | 2 |

| ICH Areas | Revitalized Cultural Manifestations | Nizag Agro-Craft Center | CEDEIN | CEDIBAL | Guarguallá Craft and Community Tourism Center | Calshi | Chuqui-Pogio | Razu Ñan | Casa Cóndor | UCASAJ | Sumak Kawsay—Royal Palace | Quilla Pacari |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditions and oral expressions | Tales and legends associated with natural elements such as mountains, where the loves of these mythical beings are shared | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Tales associated with the local fauna in connection with the territories (owl, wolf, Andean condor, lama) | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Stories associated with cultural practices such as marriage, weaving, the way of tilling the land, the creation of natural sites, the presence of Chimborazo, characters from popular festivals, sacred rituals | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Ritual social uses and festive acts | Community practices such as minka, makita mañachi, and randi randi” (forms of reciprocity*) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Rites of passage (marriages and funerals, among others) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Apotropaic rites of energy renewal for the body and soul | X | |||||||||||

| Propitiatory rites of gratitude to the Pachamama | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Knowledge and uses related to nature | Symbolic spaces related to rituals, legends, or myths, among which are Chiripunga; Cerro Sagrado Puruwa considered a guardian apu; and Qhapac Ñan | X | ||||||||||

| Symbolic space related to rituals, legends, or myths such as Machay Temple | X | |||||||||||

| Symbolic space related to rituals, legends, or myths such as the Sacred Stone Yana Rumi | X | X | ||||||||||

| Creative manifestations | Music and songs that narrate daily life or special events in the community | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Traditional games | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Traditional craft techniques | Traditional craft techniques linked to textiles and natural fiber fabrics, among others | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Traditional house construction techniques | X | X | ||||||||||

| Food and gastronomic heritage | Ritual and daily gastronomy | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Knowledge linked to the symbolic value of the agricultural products of the area | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Canton | Name of the Enterprise | Touristic Offer * | Attractions | Complementary Activities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Cultural | Total | ||||

| Alausí | Nizag Agro-Craft Center | FG | 7 | 4 | 11 | Hike to Chiripungo, viewpoint of the condor, and Qhapac Ñan horseback riding Demonstration of cultural activities Dance and museum at Sibambe station |

| Colta | CEDEIN | FG | 3 | 1 | 4 | Community coexistence Walks Demonstration of craft activities Visit to Yana Rumy in the canton of Riobamba, a community-owned space |

| Colta | CEDIBAL | FG | 9 | 3 | 12 | Walks Visits to fairs Visit to the quinoa and family farms |

| Guamote | Guarguallá Craft and Community Tourism Center | FAG | 21 | 21 | Purchase of handicrafts Walks Horseback riding Visit to the waterfall Excursion to the Sangay volcano | |

| Guano | Calshi | FAG | 6 | 4 | 10 | Cultural practices of skiing and weaving Participation in traditional festivals Ascent to Chimborazo Visit to the Bolívar stone Sale of handicrafts Walks High mountain climbing Preparation for mountaineering Elaboration of crafts Landscape photography Excursion to the ice mines Walks to the Cóndor Samana waterfall |

| Chuquipogio | ||||||

| Razu Ñan | ||||||

| Riobamba | Casa Cóndor | FAG | 9 | 2 | 11 | Walks Bike ride Bird watching Cultural activities High mountain climbing Shearing activities and treatment of alpaca fiber Community coexistence Organic garden tour Hike to Mount Shobol Urku Visit to the pogyo Tayta Andrés |

| UCASAJ | ||||||

| Sumak Kawsay—Royal Palace | FAG | 1 | 8 | 9 | Walks Visit to the llama museum Crafts in sheep wool, alpaca, and llama fiber Llama meat-based diet Way of Simon Bolivar Visit to spinning mill Cultural coexistence | |

| Quilla Pacari | ||||||

| Product Name | Duration | Points of Interest | Contents | CTO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trekking llama | Full day | Museum of the Llama Craft center Gastronomy Ascent to Chimborazo Interpretive trails | Guidance Accommodation Feeding High mountain climbing Preparation for mountaineering Walks | Sumak Kawsay—Royal Palace |

| Sharing life in community in the foothills of Chimborazo | 2 days and one night | Visit to agricultural and livestock activities Artisanal process for obtaining sheep’s wool Ice mines Snowy Chimborazo Cultural coexistence activities | Transport Guidance Accommodation Feeding Culture night Hike Ice mines Ascent to Chimborazo Viewpoints | Razu Ñan |

| Surrounding the Tayta Chimborazo | 4 days and 3 nights | Museum of the Llama Craft process of sheep wool Snowy Chimborazo Polylepis Forest Agroecological activities Visit to organic gardens Agro-ancestral practices | Transport Guidance Accommodation Feeding Culture night Walks | Sumak Kawsay Razu Ñan Casa Cóndor UCASAJ Quilla Pacari Balda Lupaxi (CEDIBAL) |

| Nizag: “Culture and Ancestral Knowledge” | 2 days and 1 night | Chiripungo Mountain Cóndor Viewpoint Qhapaq Ñan Seville Sibambe Visit to organic gardens Craft workshop Nizag Community | Transport Guidance Accommodation Feeding Culture night Walks | Nizag |

| Chimborazo’s last snowfield | Full day | Ice mines Snowy Chimborazo | Guidance Accommodation Feeding Walks | Razu Ñan |

| Organizations | No. of Procedure | Organizations | With License |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGUITUCH | 6 | AGUITUCH | 8 |

| UCASAJ | 2 | UCASAJ | 4 |

| Casa Cóndor | 2 | Casa Cóndor | 3 |

| Calshi | 2 | Calshi | 2 |

| CEDIBAL | 1 | CEDIBAL | 1 |

| Shobol pamba | 1 | Razu Ñan | 2 |

| Cacha | 1 | Nizag | 2 |

| San Rafael de Chuquipogio | 1 | ||

| Overall total | 15 | Santa Lucía de Chuquipogio | 1 |

| Overall total | 24 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maldonado-Erazo, C.P.; del Río-Rama, M.d.l.C.; Miranda-Salazar, S.P.; Tierra-Tierra, N.P. Strengthening of Community Tourism Enterprises as a Means of Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: A Case Study of Community Tourism Development in Chimborazo. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074314

Maldonado-Erazo CP, del Río-Rama MdlC, Miranda-Salazar SP, Tierra-Tierra NP. Strengthening of Community Tourism Enterprises as a Means of Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: A Case Study of Community Tourism Development in Chimborazo. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):4314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074314

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaldonado-Erazo, Claudia Patricia, María de la Cruz del Río-Rama, Sandra Patricia Miranda-Salazar, and Nancy P. Tierra-Tierra. 2022. "Strengthening of Community Tourism Enterprises as a Means of Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: A Case Study of Community Tourism Development in Chimborazo" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 4314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074314