Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles by Mushrooms: A Crucial Dimension for Sustainable Soil Management

Abstract

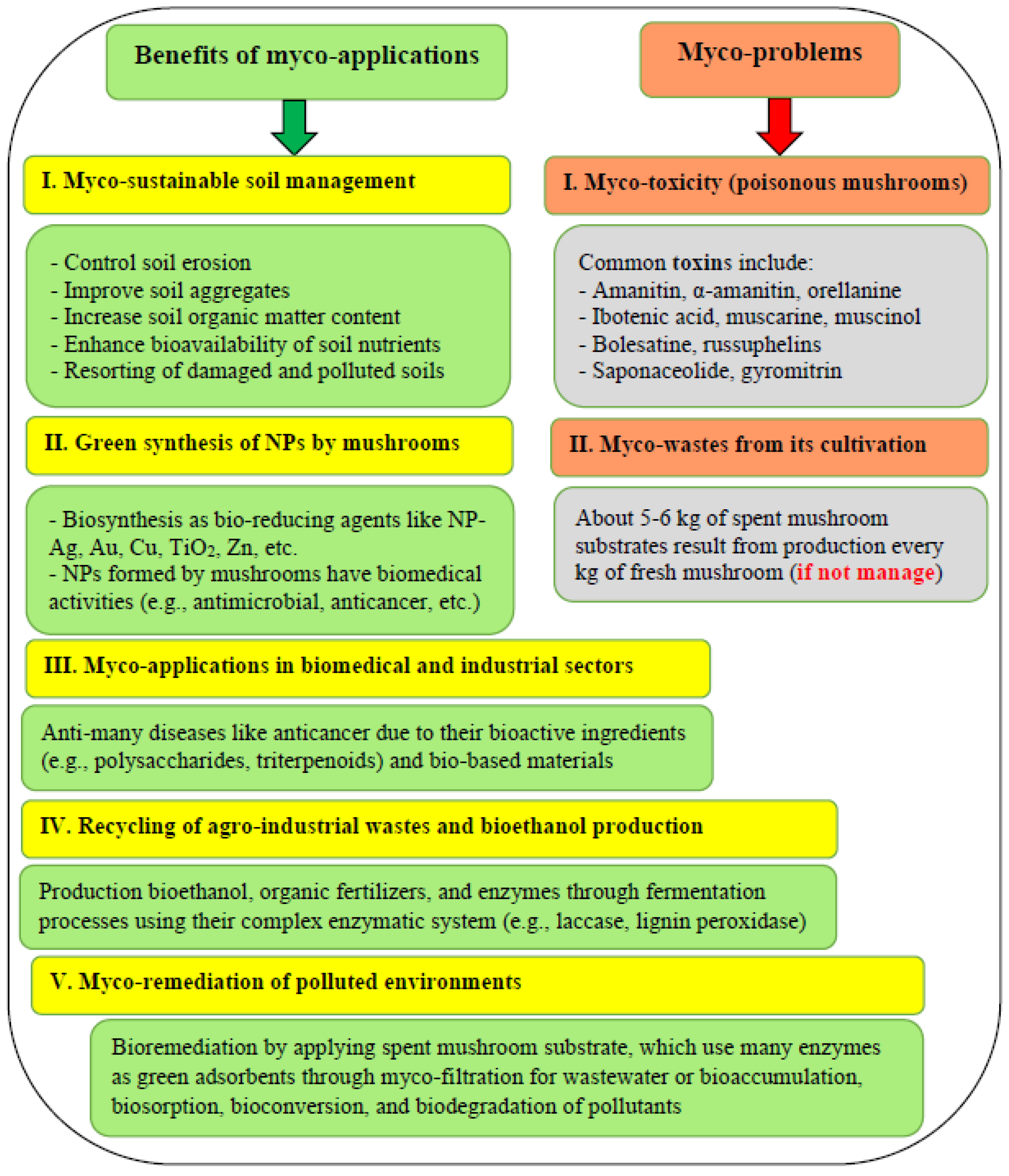

:1. Introduction

2. Soil and Its Sustainable Management

3. Soil and Mushrooms: A Vital Relationship

4. Mushrooms for Soil Improvement

4.1. Controlling Soil Erosion

4.2. Improving Soil Aggregates

4.3. Increasing Soil Organic Matter Content

4.4. Enhancing Bioavailability of Soil Nutrients

4.5. Resorting of Damaged and Polluted Soils

5. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles by Mushrooms

6. Soil Nanomanagement and Mushrooms

7. Soil Nanoremediation and Mushrooms

| Bio-Source | Applied Material | Pollutant | Mechanism or Main Findings | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. In presence of nanomaterials | ||||

| Lentinula edodes | Biochar nano Fe3O4 (LBC) | Cr(VI) (200 mg L−1) | Max. removing rate of Cr(VI) by LBC-Fe3O4 was 99.44% in aqueous media | [198] |

| Lentinula edodes Agrocybe cylindracea | Nano Fe3O4 at 2, 4, 6–22, 24 g L−1 | Cr(VI) at 200 mg L−1 | Removing Cr(VI) up to 73.88 at 240 min, 40 °C, pH 3 from 200 mg L−1 liquid by combined adsorption and redox | [199] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Desm.) Meyen | Pd-NPs (32 nm) | Azo dye direct blue 71 | Pd-NPs degraded 98% of direct blue 71 dye photochemically within 60 min under UV light in an aqueous medium | [200] |

| Tricholoma crissum Sacc. | CuO-NPs | Thorium (Th4+) | An indicator for detecting Th4+ in aqueous medium | [201] |

| II. In absent of nanomaterials | ||||

| Pleurotus ostreatus Pleurotus eryngii | Fresh SMS at rate of 4:1 (soil: SMS) | PAHs (2.63 mg kg−1) in soil | Effective remediating due to activity of laccase and manganese peroxidase in the treatment of fresh P. eryngii SMS | [81] |

| Agaricus bisporus Pleurotus eryngii | Soil amended by 5% SMS (w/w) | Total Cd in soil 72.87 mg kg−1 | Applied SMS of both mushrooms improved rice production by 38.8%; decreased Cd in soil by about 99% | [100] |

| Pleurotus ostreatus | Soil amended by dried SMS (3–12 g kg−1) | Soil Co was 8.53 mg kg−1 | Maximum pakchoi biomass recorded at applied SMS up to 9.51 g kg−1 and Co phytoavailability in soil was minimum | [111] |

| Mushroom residues | Soil amended by 10% of residues | Pb/Zn slag: 3.1 and 4.6 g kg−1, res. | Mushroom residue enhances phyto-remediation of Paulownia fortunei in Pb-Zn slag; alleviates their toxicity to plants | [117] |

| Pleurotus ostreatus | Mine polluted soil mixed with the spawn of P. ostreatus | Cr and Mn: 1.5 and 8.8 g kg−1, res. | Studied mushroom is a bio-accumulator of toxic metals (Cr, Mn, Ni, Co) from polluted soil, but not recommended to harvest/eat mushroom from polluted soil | [202] |

| Auricularia auricular and Sarcomyxa edulis | SMS mixed with polluted soil | PAH-polluted soil | Humic acid and SMS enhanced bioremediation by bacteria through laccase activity via biodegradation | [195] |

| Ganoderma lucidum, Pleurotus ostreatus, Auricularia polytricha | SMS (25 g) put into the mold | Formaldehyde free bio-board | The produced bio-board material from SMS of G. lucidum recorded the highest strength (2.51 mPa); high resistance to both fire and water | [203] |

| Discarded sticks of mushrooms | MnO2-modifed biochar | Antimony, Sb 100 mg L−1 in aqueous solution | MnO2-modified biochar produced from discarded sticks of mushrooms was excellent adsorbent; adsorption capacity 64.12 mg g−1 | [204] |

8. General Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sofo, A.; Mininni, A.N.; Ricciuti, P. Soil Macrofauna: A Key Factor for Increasing Soil Fertility and Promoting Sustainable Soil Use in Fruit Orchard Agrosystems. Agronomy 2020, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Qiu, G.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, W.; Jia, L.; Ji, X.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Shifting from Homogeneous to Heterogeneous Surfaces in Estimating Terrestrial Evapotranspiration: Review and Perspectives. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2022, 65, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Basang, C.M.; Lu, J.; Zheng, C.; Wen, Z. Different Biomass Production and Soil Water Patterns between Natural and Artificial Vegetation along an Environmental Gradient on the Loess plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 814, 152839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Zhao, D. Application of Construction Waste in the Reinforcement of Soft Soil Foundation in Coastal Cities. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbmann, M.T.; Maring, L.; Prokop, G.; Brils, J.; Bender, J.; Bispo, A.; Helming, K. Systems Knowledge for Sustainable Soil and Land Management. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Naushad, M.; Lima, E.C.; Zhang, S.; Shaheen, S.M.; Rinklebe, J. Global Soil Pollution by Toxic Elements: Current Status and Future Perspectives on the Risk Assessment and Remediation Strategies—A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 126039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Lou, Z.; Xiao, R.; Ren, Z.; Lv, X. Source Analysis and Source-Oriented Risk Assessment of Heavy Metal Pollution in Agricultural Soils of Different Cultivated Land Qualities. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, R.; Sarkar, B.; Jat, H.S.; Sharma, P.C.; Bolan, N.S. Soil Salinity under Climate Change: Challenges for Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.; Shao, Z.; Li, D.; Huang, X.; Cai, B.; Altan, O.; Wu, S. Unequal Weakening of Urbanization and Soil Salinization on Vegetation Production Capacity. Geoderma 2022, 411, 115712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prăvălie, R.; Nita, I.-A.; Patriche, C.; Niculiță, M.; Birsan, M.-V.; Roșca, B.; Bandoc, G. Global Changes in Soil Organic Carbon and Implications for Land Degradation Neutrality and Climate Stability. Environ. Res. 2021, 201, 111580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.S.S.; Seifollahi-Aghmiuni, S.; Destouni, G.; Ghajarnia, N.; Kalantari, Z. Soil Degradation in the European Mediterranean Region: Processes, Status and Consequences. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannam, I. Soil Governance and Land Degradation Neutrality. Soil Secur. 2022, 6, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnashar, A.; Zeng, H.; Wu, B.; Gebremicael, T.G.; Marie, K. Assessment of Environmentally Sensitive Areas to Desertification in the Blue Nile Basin Driven by the MEDALUS-GEE Framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 815, 152925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Dai, Q. Drivers of Soil Erosion and Subsurface Loss by Soil Leakage during Karst Rocky Desertification in SW China. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eekhout, J.P.C.; de Vente, J. Global Impact of Climate Change on Soil Erosion and Potential for Adaptation through Soil Conservation. Earth Sci. Rev. 2022, 226, 103921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-L.; Ge, Z.-M.; Xie, L.-N.; Li, S.-H.; Tan, L.-S. Effects of Waterlogging and Salinity Increase on CO2 Efflux in Soil from Coastal Marshes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 170, 104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eswar, D.; Karuppusamy, R.; Chellamuthu, S. Drivers of Soil Salinity and Their Correlation with Climate Change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 50, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janizadeh, S.; Chandra Pal, S.; Saha, A.; Chowdhuri, I.; Ahmadi, K.; Mirzaei, S.; Mosavi, A.H.; Tiefenbacher, J.P. Mapping the Spatial and Temporal Variability of Flood Hazard Affected by Climate and Land-Use Changes in the Future. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Ma, X.; Zhao, C.; Li, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, J. Risk Assessment of Soil Erosion in Central Asia under Global Warming. CATENA 2022, 212, 106056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Wei, C.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Meng, C.; Cai, Y. The Dominant Influencing Factors of Desertification Changes in the Source Region of Yellow River: Climate Change or Human Activity? Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 813, 152512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, C.; Lindo, Z. Response of Soil Biodiversity to Global Change. Pedobiologia 2022, 90, 150792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Guo, Z.; Xu, A.; Pan, K.; Pan, X. The Effects of Climate on Soil Microbial Diversity Shift after Intensive Agriculture in Arid and Semiarid Regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, M.; Sanyal, M. Extensive Study on Plant Mediated Green Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles and Their Application for Degradation of Cationic and Anionic Dyes. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2022, 17, 100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Shahid, A.; Zhu, H.; Wang, N.; Javed, M.R.; Ahmad, N.; Xu, J.; Alam, A.; Mehmood, M.A. Prospects of Algae-Based Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles for Environmental Applications. Chemosphere 2022, 293, 133571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, G.M.; Sajini, T.; Mathew, B. Advanced Green Approaches for Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesis and Their Environmental Applications. Talanta Open 2022, 5, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.V.; Nguyen, D.T.C.; Kumar, P.S.; Din, A.T.M.; Jalil, A.A.; Vo, D.-V.N. Green Synthesis of ZrO2 Nanoparticles and Nanocomposites for Biomedical and Environmental Applications: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 1309–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudheer, S.; Bai, R.G.; Muthoosamy, K.; Tuvikene, R.; Gupta, V.K.; Manickam, S. Biosustainable Production of Nanoparticles via Mycogenesis for Biotechnological Applications: A Critical Review. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 111963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, C.; Roy, A.; Ghotekar, S.; Khusro, A.; Islam, M.N.; Emran, T.B.; Lam, S.E.; Khandaker, M.U.; Bradley, D.A. Biological Agents for Synthesis of Nanoparticles and Their Applications. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadoun, S.; Arif, R.; Jangid, N.K.; Meena, R.K. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadirek, Ş.; Okkay, H. Ultrasound Assisted Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticle Attached Activated Carbon for Levofloxacin Adsorption. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2019, 105, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, T.; Ghosh, N.N.; Das, M.; Adhikary, R.; Mandal, V.; Chattopadhyay, A.P. Green Synthesis of Antibacterial and Antifungal Silver Nanoparticles Using Citrus Limetta Peel Extract: Experimental and Theoretical Studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Tripathi, J.; Sharma, M.; Nagar, S.; Sharma, A. Study of Structural, Optical Properties and Antibacterial Effects of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized by Green Synthesis Method. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 2294–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oves, M.; Ahmar Rauf, M.; Aslam, M.; Qari, H.A.; Sonbol, H.; Ahmad, I.; Sarwar Zaman, G.; Saeed, M. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles by Conocarpus lancifolius Plant Extract and Their Antimicrobial and Anticancer Activities. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Urfan, M.; Anand, R.; Sangral, M.; Hakla, H.R.; Sharma, S.; Das, R.; Pal, S.; Bhagat, M. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Eucalyptus lanceolata Leaf Litter: Characterization, Antimicrobial and Agricultural Efficacy in Maize. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2022, 28, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velsankar, K.; Venkatesan, A.; Muthumari, P.; Suganya, S.; Mohandoss, S.; Sudhahar, S. Green Inspired Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles and Its Characterizations with Biofilm, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anti-Diabetic Activities. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1255, 132420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, W.T.J.; Nyam, K.L. Evaluation of Silver Nanoparticles in Cosmeceutical and Potential Biosafety Complications. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 2085–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Desouky, N.; Shoueir, K.; El-Mehasseb, I.; El-Kemary, M. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Bio Valorization coffee Waste Extract: Photocatalytic Flow-Rate Performance, Antibacterial Activity, and Electrochemical Investigation. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, M.; Ghazal, H.; Othman, H.A.; Hassabo, A.G. Synthesis of Different Nanometals Using Citrus Sinensis Peel (Orange peel) Waste Extraction for Valuable Functionalization of Cotton Fabric. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 639–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Tripathi, A. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles and Its Key Applications in Various Sectors. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 48, 1626–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Sustainable Development Goal 6—Synthesis Report on Water and Sanitation. United Nations, New York. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/5623 (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Food & Agriculture Organization. The Future of Food and Agriculture—Alternative Pathways to 2050; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018; ISBN 978-92-5-130158-6. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018: Building Climate Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; ISBN 978-92-5-130571-3. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO and ITPS. Status of the World’s Soil Resources (SWSR): Main Report; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Intergovernmental Technical Panel on Soils: Rome, Italy, 2015; ISBN 978-92-5-109004-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, R.; Horn, R.; Kosaki, T. Soil and Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.schweizerbart.de/publications/detail/isbn/9783510654253/Soil_and_Sustainable_Development_Goals_ (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Bonfante, A.; Basile, A.; Bouma, J. Targeting the Soil Quality and Soil Health Concepts When Aiming for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the EU Green Deal. Soil 2020, 6, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R.; Bouma, J.; Brevik, E.; Dawson, L.; Field, D.J.; Glaser, B.; Hatano, R.; Hartemink, A.E.; Kosaki, T.; Lascelles, B.; et al. Soils and Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations: An International Union of Soil Sciences Perspective. Geoderma Reg. 2021, 25, e00398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Khan, H.Z. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Reporting and the Role of Country-Level Institutional Factors: An International Evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 335, 130290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatayama, H. The Metals Industry and the Sustainable Development Goals: The Relationship Explored Based on SDG Reporting. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 178, 106081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluk, K.A.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Introduction to the Special Issue on “Deepening Our Understandings of the Roles and Responsibilities of the Tourism Industry towards the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)”. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 41, 100944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; Obaideen, K.; Elsaid, K.; Wilberforce, T.; Sayed, E.T.; Maghrabie, H.M.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Assessment of the Pre-Combustion Carbon Capture Contribution into Sustainable Development Goals SDGs Using Novel Indicators. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 153, 111710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, M.; Shams Esfandabadi, Z.; Sadeghi, S.; Ranjbari, M.; Zanetti, M.C. COVID-19 and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Scenario Analysis through Fuzzy Cognitive Map Modeling. Gondwana Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.T.; Wasser, S.P. The Cultivation and Environmental Impact of Mushrooms. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-19-938941-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, G.; Goggi, S.; Giampieri, F.; Baroni, L. A Review of Mushrooms in Human Nutrition and Health. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 117, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cateni, F.; Gargano, M.L.; Procida, G.; Venturella, G.; Cirlincione, F.; Ferraro, V. Mycochemicals in Wild and Cultivated Mushrooms: Nutrition and Health. Phytochem. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, P.; Sen, I.K.; Chakraborty, I.; Mondal, S.; Bar, H.; Bhanja, S.K.; Mandal, S.; Maity, G.N. Biologically Active Polysaccharide from Edible Mushrooms: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 172, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Rauf, A.; Khalil, A.A.; Ko, E.-Y.; Keum, Y.-S.; Anwar, S.; Alamri, A.; Rengasamy, K.R.R. Edible Mushrooms Show Significant Differences in Sterols and Fatty Acid Compositions. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 141, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, F.; Ng, T.B. Interrelationship among Paraptosis, Apoptosis and Autophagy in Lung Cancer A549 Cells Induced by BEAP, an Antitumor Protein Isolated from the Edible Porcini Mushroom Boletus edulis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 188, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, R.; Nowacka-Jechalke, N.; Pietrzak, W.; Gawlik-Dziki, U. A New Look at Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms as a Source of Ergosterol and Ergosterol Peroxide—UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis. Food Chem. 2022, 369, 130927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wang, J.; He, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, S.; Penttinen, P.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Zou, L. Organic Fertilizers Shape Soil Microbial Communities and Increase Soil Amino Acid Metabolites Content in a Blueberry Orchard. Microb. Ecol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkoris, V.; Massas, I.; Polemis, E.; Koutrotsios, G.; Zervakis, G.I. Accumulation of Heavy Metals by Wild Edible Mushrooms with Respect to Soil Substrates in the Athens Metropolitan Area (Greece). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 685, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowlati, M.; Sobhi, H.R.; Esrafili, A.; FarzadKia, M.; Yeganeh, M. Heavy Metals Content in Edible Mushrooms: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Health Risk Assessment. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwenzi, W.; Tagwireyi, C.; Musiyiwa, K.; Chipurura, B.; Nyamangara, J.; Sanganyado, E.; Chaukura, N. Occurrence, Behavior, and Human Exposure and Health Risks of Potentially Toxic Elements in Edible Mushrooms with Focus on Africa. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, H.; Shariatifar, N.; Nazmara, S.; Moazzen, M.; Mahmoodi, B.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. The Concentration and Probabilistic Health Risk of Potentially Toxic Elements (PTEs) in Edible Mushrooms (Wild and Cultivated) Samples Collected from Different Cities of Iran. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 199, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovko, O.; Kaczmarek, M.; Asp, H.; Bergstrand, K.-J.; Ahrens, L.; Hultberg, M. Uptake of Perfluoroalkyl Substances, Pharmaceuticals, and Parabens by Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) and Exposure Risk in Human Consumption. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andronikov, A.V.; Andronikova, I.E.; Sebek, O. First Data on Isotope and Trace Element Compositions of a Xerocomus subtomentosus Mushroom Sample from Western Czech Republic. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 9369–9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, A.-L.; Reiter, G.; Piepenbring, M.; Bässler, C. Spatial Risk Assessment of Radiocesium Contamination of Edible Mushrooms—Lessons from a Highly Frequented Recreational Area. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronda, O.; Grządka, E.; Ostolska, I.; Orzeł, J.; Cieślik, B.M. Accumulation of Radioisotopes and Heavy Metals in Selected Species of Mushrooms. Food Chem. 2022, 367, 130670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melgar, M.J.; García, M.Á. Natural Radioactivity and Total K Content in Wild-Growing or Cultivated Edible Mushrooms and Soils from Galicia (NW, Spain). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 52925–52935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Yang, B.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Tuo, F. Radionuclide Content and Risk Analysis of Edible Mushrooms in Northeast China. Radiat. Med. Prot. 2021, 2, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ramady, H.; Llanaj, X.; Prokisch, J. Edible Mushroom Cultivated in Polluted Soils and Its Potential Risks on Human Health: A Short Communication. Egypt.J. Soil Sci. 2021, 61, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, F.; Sarikurkcu, C.; Akata, I.; Tepe, B. Metal Concentrations of Wild Mushroom Species Collected from Belgrad Forest (Istanbul, Turkey) with Their Health Risk Assessments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 36193–36204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, F.; Sarikurkcu, C.; Akata, I.; Tepe, B. Element Concentration, Daily Intake of Elements, and Health Risk Indices of Wild Mushrooms Collected from Belgrad Forest and Ilgaz Mountain National Park (Turkey). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 51544–51555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mleczek, M.; Gąsecka, M.; Budka, A.; Siwulski, M.; Mleczek, P.; Magdziak, Z.; Budzyńska, S.; Niedzielski, P. Mineral Composition of Elements in Wood-Growing Mushroom Species Collected from of Two Regions of Poland. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 4430–4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutrotsios, G.; Tagkouli, D.; Bekiaris, G.; Kaliora, A.; Tsiaka, T.; Tsiantas, K.; Chatzipavlidis, I.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Kalogeropoulos, N.; Zervakis, G.I. Enhancing the Nutritional and Functional Properties of Pleurotus citrinopileatus Mushrooms through the Exploitation of Winery and Olive Mill Wastes. Food Chem. 2022, 370, 131022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mleczek, M.; Budka, A.; Siwulski, M.; Budzyńska, S.; Kalač, P.; Karolewski, Z.; Lisiak-Zielińska, M.; Kuczyńska-Kippen, N.; Niedzielski, P. Anthropogenic Contamination Leads to Changes in Mineral Composition of Soil- and Tree-Growing Mushroom Species: A Case Study of Urban vs. Rural Environments and Dietary Implications. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 809, 151162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Wang, Y.; Tian, M.; Shah Jahan, M.; Shu, S.; Sun, J.; Li, P.; Ahammed, G.J.; Guo, S. Mixing of Biochar, Vinegar and Mushroom Residues Regulates Soil Microbial Community and Increases Cucumber Yield under Continuous Cropping Regime. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 161, 103883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, X. Changes in Physical, Chemical, and Microbiological Properties during the Two-Stage Co-Composting of Green Waste with Spent Mushroom Compost and Biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 171, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dong, S.; Yao, Y.; Shi, W.; Wu, M.; Xu, H. Inoculation of Bacteria for the Bioremediation of Heavy Metals Contaminated Soil by Agrocybe aegerita. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 65816–65824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Sarma, M.K.; Deb, U.; Steinhauser, G.; Walther, C.; Gupta, D.K. Mushrooms: From Nutrition to Mycoremediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017, 24, 19480–19493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Ge, W.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, Q.; Ma, D.; Chai, C. Effects of Spent Mushroom Substrate on the Dissipation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Agricultural Soil. Chemosphere 2020, 259, 127462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, E.; Paredes, C.; Bustamante, M.A.; Moral, R.; Moreno-Caselles, J. Relationships between Soil Physico-Chemical, Chemical and Biological Properties in a Soil Amended with Spent Mushroom Substrate. Geoderma 2012, 173–174, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Mortimer, P.E.; Hyde, K.D.; Kakumyan, P.; Thongklang, N. Mushroom Cultivation for Soil Amendment and Bioremediation. Circ. Agric. Syst. 2021, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, X.; Han, C.; Wang, C.; Yu, X. Improving Soil Surface Erosion Resistance by Fungal Mycelium. In Geo-Congress 2020: Foundations, Soil Improvement, and Erosion, Proceedings of the Geo-Congress 2020, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 25–28 February 2020; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; pp. 523–531. [Google Scholar]

- Caesar-TonThat, T.C.; Espeland, E.; Caesar, A.J.; Sainju, U.M.; Lartey, R.T.; Gaskin, J.F. Effects of Agaricus Lilaceps Fairy Rings on Soil Aggregation and Microbial Community Structure in Relation to Growth Stimulation of Western Wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii) in Eastern Montana Rangeland. Microb. Ecol. 2013, 66, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshila Ravi, R.; Anusuya, S.; Balachandar, M.; Muthukumar, T. Microbial Interactions in Soil Formation and Nutrient Cycling. In Mycorrhizosphere and Pedogenesis; Varma, A., Choudhary, D.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 363–382. ISBN 9789811364792. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, V.; Basenko, E.Y.; Benz, J.P.; Braus, G.H.; Caddick, M.X.; Csukai, M.; de Vries, R.P.; Endy, D.; Frisvad, J.C.; Gunde-Cimerman, N.; et al. Growing a Circular Economy with Fungal Biotechnology: A White Paper. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2020, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lehmann, A.; Zheng, W.; Rillig, M.C. Soil Biota Contributions to Soil Aggregation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1828–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, C.; Ni, S.; Zhang, H.; Dong, C. Ultrastructure and Development of Acanthocytes, Specialized Cells in Stropharia Rugosoannulata, Revealed by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Cryo-SEM. Mycologia 2021, 113, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Porte, A.; Schmidt, R.; Yergeau, É.; Constant, P. A Gaseous Milieu: Extending the Boundaries of the Rhizosphere. Trends Microbiol. 2020, 28, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rillig, M.C.; Muller, L.A.; Lehmann, A. Soil Aggregates as Massively Concurrent Evolutionary Incubators. ISME J. 2017, 11, 1943–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Ding, X. Organic Fertilization Increased Soil Organic Carbon Stability and Sequestration by Improving Aggregate Stability and Iron Oxide Transformation in Saline-Alkaline Soil. Plant Soil 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, F.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Liao, Y.-C. Microbial Carbon-Use Efficiency and Straw-Induced Priming Effect within Soil Aggregates Are Regulated by Tillage History and Balanced Nutrient Supply. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2021, 57, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Liu, R.; Cao, W.; Zhu, K.; Fenton, O.; Guo, J.; Chen, Q. Nitrogen and Carbon Addition Changed Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Soil Aggregates in Straw-Incorporated Soil. J. Soils Sedim. 2022, 22, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udom, B.E.; Udom, G.J.; Otta, J.T. Breakdown of Dry Aggregates by Water Drops after Applications of Poultry Manure and Spent Mushroom Wastes. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 217, 105267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Díaz, A.; Allas, R.B.; Gristina, L.; Cerdà, A.; Pereira, P.; Novara, A. Carbon Input Threshold for Soil Carbon Budget Optimization in Eroding Vineyards. Geoderma 2016, 271, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keesstra, S.; Pereira, P.; Novara, A.; Brevik, E.C.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Parras-Alcántara, L.; Jordán, A.; Cerdà, A. Effects of Soil Management Techniques on Soil Water Erosion in Apricot orchards. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 551–552, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lou, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, X.; Baig, S.A.; Hu, B.; Xu, X. Composition Variability of Spent Mushroom Substrates during Continuous Cultivation, Composting Process and Their Effects on Mineral Nitrogen Transformation in Soil. Geoderma 2017, 307, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Kohler, A.; Miao, R.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xie, L.; Tang, J.; et al. Multi-Omic Analyses of Exogenous Nutrient Bag Decomposition by the Black Morel Morchella Importuna Reveal Sustained Carbon Acquisition and Transferring. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 3909–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, H.; Liu, P.; Shan, W.; Teng, Y.; Rao, D.; Zou, L. Remediation Potential of Spent Mushroom Substrate on Cd Pollution in a Paddy Soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 36850–36860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngan, N.M.; Riddech, N. Use of Spent Mushroom Substrate as an Inoculant Carrier and an Organic Fertilizer and Their Impacts on Roselle Growth (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) and Soil Quality. Waste Biomass Valor. 2021, 12, 3801–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-W.; Xu, M.; Cai, X.-Y.; Tian, F. Evaluation of Soil Microbial Communities and Enzyme Activities in Cucumber Continuous Cropping Soil Treated with Spent Mushroom (Flammulina velutipes) Substrate. J. Soils Sedim. 2021, 21, 2938–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermeier, M.M.; Minarsch, E.-M.L.; Durai Raj, A.C.; Rineau, F.; Schröder, P. Changes of Soil-Rhizosphere Microbiota after Organic Amendment Application in a Hordeum vulgare L. Short-Term Greenhouse Experiment. Plant Soil 2020, 455, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.S.; Alqaisi, M.R.; Zahwan, T.A. Evaluation of Seed Yield, Oil, and Fatty Acid Ratio in Medicinal Pumpkin Grown According to Traditional Cultivation and Different Programs of Organic Farming. Org. Agr. 2022, 12, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Tiwari, A.; Gupta, A.; Kumar, A.; Hariprasad, P.; Sharma, S. Bioformulation Development via Valorizing Silica-Rich Spent Mushroom Substrate with Trichoderma asperellum for Plant Nutrient and Disease Management. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.-Y.; Wei, J.-K.; Xue, F.-Y.; Li, W.-C.; Guan, T.-K.; Hu, B.-Y.; Chen, Q.-J.; Han, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, G.-Q. Microbial Inoculation Influences Microbial Communities and Physicochemical Properties during Lettuce Seedling Using Composted Spent Mushroom Substrate. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 174, 104418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Vieira, V.; Almeida Conceição, A.; Raisa Barbosa Cunha, J.; Enis Virginio Machado, A.; Gonzaga de Almeida, E.; Souza Dias, E.; Magalhães Alcantara, L.; Neil Gerard Miller, R.; Gonçalves de Siqueira, F. A New Circular Economy Approach for Integrated Production of Tomatoes and Mushrooms. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 2756–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, X.; Qu, J.; Jin, Y. Spent Mushroom Substrate Combined with Alkaline Amendment Passivates Cadmium and Improves Soil Property. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 16317–16325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Kong, L.; Guan, Q.; Yang, R.; Jin, Y.; Liu, X.; Qu, J. Remediation of Cadmium Contaminated Soil by Composite Spent Mushroom Substrate Organic Amendment under High Nitrogen Level. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 430, 128345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fang, H.; Gao, Y.; Luo, L.; Feng, W.; Hu, X.; Wan, S.; Huang, W.; et al. Effects of Spent Mushroom Substrate-Derived Biochar on Soil CO2 and N2O Emissions Depend on Pyrolysis Temperature. Chemosphere 2020, 246, 125608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Huang, Q.; Su, Y.; Xue, Q.; Sun, L. Cobalt Speciation and Phytoavailability in Fluvo-Aquic Soil under Treatments of Spent Mushroom Substrate from Pleurotus Ostreatus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 7486–7496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Hanafi, F.H.; Rezania, S.; Mat Taib, S.; Md Din, M.F.; Yamauchi, M.; Sakamoto, M.; Hara, H.; Park, J.; Ebrahimi, S.S. Environmentally Sustainable Applications of Agro-Based Spent Mushroom Substrate (SMS): An Overview. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2018, 20, 1383–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, C.P.C.; Lim, L.Y.; Ho, W.S.; Lim, J.S.; Klemeš, J.J.; Towprayoon, S.; Ho, C.S.; Lee, C.T. A Review on the Global Warming Potential of Cleaner Composting and Mitigation Strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 146, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-L.; Chen, X.-M.; Sun, J.; Liu, J.-Y.; Sun, S.-Y.; Yang, Z.-Y.; Wang, Y. Spent Mushroom Substrate Biochar as a Potential Amendment in Pig Manure and Rice Straw Composting Processes. Environ. Technol. 2017, 38, 1765–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, H. The Effects of Spent Mushroom Compost on Growth and Nutrient Contents of Pepper Seedlings. Mediterr. Agric. Sci. 2017, 30, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Dai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, W.; Yuan, X.; Yuan, H.; Cui, Z. Composted Biogas Residue and Spent Mushroom Substrate as a Growth Medium for Tomato and Pepper Seedlings. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 216, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, Y.; Su, R.; Du, L.; Liu, Z. Mushroom Residue Modification Enhances Phytoremediation Potential of Paulownia fortunei to Lead-Zinc Slag. Chemosphere 2020, 253, 126774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Du, L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Han, L. The Potential of Paulownia Fortunei Seedlings for the Phytoremediation of Manganese Slag Amended with Spent Mushroom Compost. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 196, 110538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Chen, Y.; Du, L.; Liu, Z.; He, L. Spent Mushroom Compost and Calcium Carbonate Modification Enhances Phytoremediation Potential of Macleaya cordata to Lead-Zinc Mine Tailings. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 294, 113029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Sultana, S.; Wang, J.; Munir, A.; Battaglia, M.L.; Sarker, T.; Seleiman, M.F.; Barmon, M.; Zhang, R. Additions of Optimum Water, Spent Mushroom Compost and Wood Biochar to Improve the Growth Performance of Althaea rosea in Drought-Prone Coal-Mined Spoils. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Wang, J.; Han, X.; Gou, J.; Pei, Z.; Lu, G.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C. The Relationship between Material Transformation, Microbial Community and Amino Acids and Alkaloid Metabolites in the Mushroom Residue-Prickly Ash Seed Oil Meal Composting with Biocontrol Agent Addition. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 350, 126913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Yadav, A.N.; Mondal, R.; Kour, D.; Subrahmanyam, G.; Shabnam, A.A.; Khan, S.A.; Yadav, K.K.; Sharma, G.K.; Cabral-Pinto, M.; et al. Myco-Remediation: A Mechanistic Understanding of Contaminants Alleviation from Natural Environment and Future Prospect. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mnkandla, S.M.; Otomo, P.V. Effectiveness of Mycofiltration for Removal of Contaminants from Water: A Systematic Review Protocol. Environ. Evid. 2021, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, O.; Weekers, F.; Thonart, P.; Tesch, E.; Kuenemann, P.; Jacques, P. Limiting Factors of Mycopesticide Development. Biol. Control 2020, 144, 104220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoknes, K.; Scholwin, F.; Jasinska, A.; Wojciechowska, E.; Mleczek, M.; Hanc, A.; Niedzielski, P. Cadmium Mobility in a Circular Food-to-Waste-to-Food System and the Use of a Cultivated Mushroom (Agaricus subrufescens) as a Remediation Agent. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 245, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Rai, S.N.; Mishra, V.; Singh, M.P. Mycoremediation of Environmental Pollutants: A Review with Special Emphasis on Mushrooms. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 4, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewlaoyoong, A.; Chen, J.-R.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Lin, C.; Cheruiyot, N.K.; Sriprom, P. Innovative Mycoremediation Technique for Treating Unsterilized PCDD/F-Contaminated Field Soil and the Exploration of Chlorinated Metabolites. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 289, 117869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathankumar, A.K.; Saikia, K.; Cabana, H.; Kumar, V.V. Surfactant-Aided Mycoremediation of Soil Contaminated with Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Environ. Res. 2022, 209, 112926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boujelben, R.; Ellouze, M.; Tóran, M.J.; Blánquez, P.; Sayadi, S. Mycoremediation of Tunisian Tannery Wastewater under Non-Sterile Conditions Using Trametes Versicolor: Live and Dead Biomasses. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.R.; Giri, R.; Sharma, R.K. Efficient Bioremediation of Metal Containing Industrial Wastewater Using White Rot Fungi. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Vaidyanathan, V.; Venkataraman, S.; Senthil Kumar, P.; Sri Rajendran, D.; Saikia, K.; Karanam Rathankumar, A.; Cabana, H.; Varjani, S. Mycoremediation of Lignocellulosic Biorefinery Sludge: A Reinvigorating Approach for Organic Contaminants Remediation with Simultaneous Production of Lignocellulolytic Enzyme Cocktail. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 127012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Bahrani, R.; Raman, J.; Lakshmanan, H.; Hassan, A.A.; Sabaratnam, V. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Tree Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus Ostreatus and Its Inhibitory Activity against Pathogenic Bacteria. Mater. Lett. 2017, 186, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Bhargava, A. Biological Synthesis of Nanoparticles: Fungi. In Green Nanoparticles: The Future of Nanobiotechnology; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 101–137. ISBN 9789811671050. [Google Scholar]

- Owaid, M.N.; Rabeea, M.A.; Abdul Aziz, A.; Jameel, M.S.; Dheyab, M.A. Mushroom-Assisted Synthesis of Triangle Gold Nanoparticles Using the Aqueous Extract of Fresh Lentinula edodes (Shiitake), Omphalotaceae. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2019, 12, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, V.K.; Yadav, N.; Rai, N.K.; Bohara, R.A.; Rai, S.N.; Aleya, L.; Singh, M.P. Two Birds with One Stone: Oyster Mushroom Mediated Bimetallic Au-Pt Nanoparticles for Agro-Waste Management and Anticancer Activity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 13761–13775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthi, R.; Bharathakumar, S.; Malaikozhundan, B.; Mahalingam, P.U. Mycofabrication of Gold Nanoparticles: Optimization, Characterization, Stabilization and Evaluation of Its Antimicrobial Potential on Selected Human Pathogens. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 35, 102107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Ö.; Gökşen Tosun, N.; Özgür, A.; Erden Tayhan, S.; Bilgin, S.; Türkekul, İ.; Gökce, İ. Microwave-Assisted Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Crude Extracts of Boletus edulis and Coriolus versicolor: Characterization, Anticancer, Antimicrobial and Wound Healing Activities. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 64, 102641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Ö.; Gökşen Tosun, N.; İmamoğlu, R.; Türkekul, İ.; Gökçe, İ.; Özgür, A. Biosynthesis and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles from Tricholoma ustale and Agaricus arvensis Extracts and Investigation of Their Antimicrobial, Cytotoxic, and Apoptotic Potentials. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 69, 103178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, M.S.; Aziz, A.A.; Dheyab, M.A.; Khaniabadi, P.M.; Kareem, A.A.; Alrosan, M.; Ali, A.T.; Rabeea, M.A.; Mehrdel, B. Mycosynthesis of Ultrasonically-Assisted Uniform Cubic Silver Nanoparticles by Isolated Phenols from Agaricus bisporus and Its Antibacterial Activity. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 29, 101774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.A.; Nguyen, V.-C.; Phan, T.N.H.; Le, V.T.; Vasseghian, Y.; Trubitsyn, M.A.; Nguyen, A.-T.; Chau, T.P.; Doan, V.-D. Novel Biogenic Silver and Gold Nanoparticles for Multifunctional Applications: Green Synthesis, Catalytic and Antibacterial Activity, and Colorimetric Detection of Fe(III) Ions. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhansi, K.; Jayarambabu, N.; Reddy, K.P.; Reddy, N.M.; Suvarna, R.P.; Rao, K.V.; Kumar, V.R.; Rajendar, V. Biosynthesis of MgO Nanoparticles Using Mushroom Extract: Effect on Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) Seed Germination. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manimaran, K.; Natarajan, D.; Balasubramani, G.; Murugesan, S. Pleurotus sajor caju Mediated TiO2 Nanoparticles: A Novel Source for Control of Mosquito Larvae, Human Pathogenic Bacteria and Bone Cancer Cells. J. Clust. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriramulu, M.; Shanmugam, S.; Ponnusamy, V.K. Agaricus Bisporus Mediated Biosynthesis of Copper Nanoparticles and Its Biological Effects: An in-Vitro Study. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2020, 35, 100254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafeeq, C.M.; Paul, E.; Vidya Saagar, E.; Manzur Ali, P.P. Mycosynthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Pleurotus floridanus and Optimization of Process Parameters. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 12375–12380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, T.; Meydan, I.; Seckin, H.; Bekmezci, M.; Sen, F. Green Synthesis, Characterization and Bioactivity of Biogenic Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 111897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandel, P.; Shahi, S.K. Mycogenic Nanoparticles and Their Bio-Prospective Applications: Current Status and Future Challenges. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 2018, 8, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, A.; ul Ashraf, Z.; Gani, A.; Masoodi, F.A.; Gani, A. β-Glucan from Mushrooms and Dates as a Wall Material for Targeted Delivery of Model Bioactive Compound: Nutraceutical Profiling and Bioavailability. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 82, 105884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygün, A.; Özdemir, S.; Gülcan, M.; Cellat, K.; Şen, F. Synthesis and Characterization of Reishi Mushroom-Mediated Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles for the Biochemical Applications. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 178, 112970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanja, S.K.; Samanta, S.K.; Mondal, B.; Jana, S.; Ray, J.; Pandey, A.; Tripathy, T. Green Synthesis of Ag@Au Bimetallic Composite Nanoparticles Using a Polysaccharide Extracted from Ramaria botrytis Mushroom and Performance in Catalytic Reduction of 4-Nitrophenol and Antioxidant, Antibacterial Activity. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2020, 14, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaloot, A.S.; Owaid, M.N.; Naeem, G.A.; Muslim, R.F. Mycosynthesizing and Characterizing Silver Nanoparticles from the Mushroom Inonotus hispidus (Hymenochaetaceae), and Their Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2020, 14, 100313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurhade, P.; Kodape, S.; Choudhury, R. Overview on Green Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles. Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 5187–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Flores, H.E.; Contreras-Chávez, R.; Garnica-Romo, M.G. Effect of Extraction Processes on Bioactive Compounds from Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus djamor: Their Applications in the Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. J. Inorg. Organomet Polym. 2021, 31, 1406–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshchinina, E.A.; Vetchinkina, E.P.; Kupryashina, M.A.; Kursky, V.F.; Nikitina, V.E. Nanoparticles Synthesis by Agaricus Soil Basidiomycetes. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2018, 126, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musa, S.F.; Yeat, T.S.; Kamal, L.Z.M.; Tabana, Y.M.; Ahmed, M.A.; El Ouweini, A.; Lim, V.; Keong, L.C.; Sandai, D. Pleurotus sajor-caju Can Be Used to Synthesize Silver Nanoparticles with Antifungal Activity against Candida albicans. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, G.; Das, P.; Saha, A.K. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Mushroom Extract of Pleurotus Giganteus: Characterization, Antimicrobial, and α-Amylase Inhibitory Activity. Bionanoscience 2019, 9, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman Ismail Abdalla, S.; Katas, H.; Chan, J.Y.; Ganasan, P.; Azmi, F.; Fauzi Mh Busra, M. Antimicrobial Activity of Multifaceted Lactoferrin or Graphene Oxide Functionalized Silver Nanocomposites Biosynthesized Using Mushroom Waste and Chitosan. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 4969–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Debnath, G.; Das, P.; Saha, A.K. Characterization, Antimicrobial and α-Amylase Inhibitory Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized by Using Mushroom Extract of Lentinus tuber-regium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 90, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, A.; Sarwar, N.; Sadia, H.; Riaz, M.; Sharif, S.; Shahid, M.; Khan, J.A. Silver Nano-Particles: Synthesis and Characterization by Using Glucans Extracted from Pleurotus ostreatus. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 3205–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, F.N.; Nwabor, O.F. Valorization of Pichia Spent Medium via One-Pot Synthesis of Biocompatible Silver Nanoparticles with Potent Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Tyrosinase Inhibitory and Reusable Catalytic Activities. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 115, 111104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wei, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, H.; Wang, L.; Su, H. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Mushroom Flammulina velutipes Extract and Their Antibacterial Activity Against Aquatic Pathogens. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2020, 13, 1908–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Hadi, S.Y.; Owaid, M.N.; Rabeea, M.A.; Abdul Aziz, A.; Jameel, M.S. Rapid Mycosynthesis and Characterization of Phenols-Capped Crystal Gold Nanoparticles from Ganoderma applanatum, Ganodermataceae. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 27, 101683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetchinkina, E.P.; Loshchinina, E.A.; Vodolazov, I.R.; Kursky, V.F.; Dykman, L.A.; Nikitina, V.E. Biosynthesis of Nanoparticles of Metals and Metalloids by Basidiomycetes. Preparation of Gold Nanoparticles by Using Purified Fungal Phenol Oxidases. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 1047–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.H. Preparation of Novel Selenium Nanoparticles with Strong In Vitro and In Vivo Anticancer Efficacy Using Tiger Milk Mushroom. In Proceedings of the 248th National Meeting of the American-Chemical-Society (ACS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 10–14 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Senapati, U.S.; Sarkar, D. Characterization of Biosynthesized Zinc Sulphide Nanoparticles Using Edible Mushroom Pleurotuss ostreatu. Indian J. Phys. 2014, 88, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sonbaty, S.; Kandil, E.I.; Haroun, R.A.-H. Assessment of the Antitumor Activity of Green Biosynthesized Zinc Nanoparticles as Therapeutic Agent Against Renal Cancer in Rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manimaran, K.; Balasubramani, G.; Ragavendran, C.; Natarajan, D.; Murugesan, S. Biological Applications of Synthesized ZnO Nanoparticles Using Pleurotus djamor Against Mosquito Larvicidal, Histopathology, Antibacterial, Antioxidant and Anticancer Effect. J. Clust. Sci. 2021, 32, 1635–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preethi, P.S.; Narenkumar, J.; Prakash, A.A.; Abilaji, S.; Prakash, C.; Rajasekar, A.; Nanthini, A.U.R.; Valli, G. Myco-Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles as Potent Anti-Corrosion of Copper in Cooling Towers. J. Clust. Sci. 2019, 30, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Rhaman, S.M.S.; Naher, L.; Siddiquee, S. Mushroom Quality Related with Various Substrates’ Bioaccumulation and Translocation of Heavy Metals. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurd-Anjaraki, S.; Ramezan, D.; Ramezani, S.; Samzadeh-Kermani, A.; Pirnia, M.; Shahi, B.Y. Potential of Waste Reduction of Agro-Biomasses through Reishi Medicinal Mushroom (Ganoderma lucidum) Production Using Different Substrates and Techniques. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yoshida, S.; Mitani, N.; Egusa, M.; Takagi, M.; Izawa, H.; Matsumoto, T.; Kaminaka, H.; Ifuku, S. Disease Resistance and Growth Promotion Activities of Chitin/Cellulose Nanofiber from Spent Mushroom Substrate to Plant. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 284, 119233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Zin, M.I.; Jimat, D.N.; Wan Nawawi, W.M.F. Physicochemical Properties of Fungal Chitin Nanopaper from Shiitake (L. edodes), Enoki (F. velutipes) and Oyster Mushrooms (P. ostreatus). Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 281, 119038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boureghda, Y.; Satha, H.; Bendebane, F. Chitin–Glucan Complex from Pleurotus Ostreatus Mushroom: Physicochemical Characterization and Comparison of Extraction Methods. Waste Biomass Valor. 2021, 12, 6139–6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargin, I.; Karakurt, S.; Alkan, S.; Arslan, G. Live Cell Imaging With Biocompatible Fluorescent Carbon Quantum Dots Derived From Edible Mushrooms Agaricus bisporus, Pleurotus ostreatus, and Suillus luteus. J. Fluoresc. 2021, 31, 1461–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Han, X.; Bao, R.; Hao, Y.; Li, S. Preparation and Properties of Water-in-Oil Shiitake Mushroom Polysaccharide Nanoemulsion. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 140, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazli Wan Nawawi, W.M.; Lee, K.-Y.; Kontturi, E.; Murphy, R.J.; Bismarck, A. Chitin Nanopaper from Mushroom Extract: Natural Composite of Nanofibers and Glucan from a Single Biobased Source. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 6492–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- del Rocío Urbina-Salazar, A.; Inca-Torres, A.R.; Falcón-García, G.; Carbonero-Aguilar, P.; Rodríguez-Morgado, B.; del Campo, J.A.; Parrado, J.; Bautista, J. Chitinase Production by Trichoderma Harzianum Grown on a Chitin-Rich Mushroom Byproduct Formulated Medium. Waste Biomass Valor. 2019, 10, 2915–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onem, H.; Nadaroglu, H. Immobilization of Purified Phytase Enzyme from Tirmit (Lactarius volemus) on Coated Chitosan with Iron Nanoparticles and Investigation of Its Usability in Cereal Industry. Iran J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Sci. 2018, 42, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, N.; Kimura, M.; Okuzawa, R.; Nakamura, Y.; Ike, M.; Hayashi, N.; Obara, A.; Sakamoto, Y.; Habu, N. Preparation of Cellulose Nanofibers from Waste Mushroom Bed of Shiitake (Lentinus edodes) by TEMPO-Mediated Oxidation. Wood Preserv. 2016, 42, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Ramady, H.; Alshaal, T.; Abowaly, M.; Abdalla, N.; Taha, H.S.; Al-Saeedi, A.H.; Shalaby, T.; Amer, M.; Fári, M.; Domokos-Szabolcsy, É.; et al. Nanoremediation for Sustainable Crop Production. In Nanoscience in Food and Agriculture 5 (Sustainable Agriculture Reviews); Ranjan, S., Dasgupta, N., Lichtfouse, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 26, pp. 335–363. ISBN 978-3-319-58495-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.; Feng, X.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, F. Contribution of Nano-Zero-Valent Iron and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi to Phytoremediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soil. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Wang, G.; Peng, C.; Tan, J.; Wan, J.; Sun, P.; Li, Q.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, Y.; et al. Recent Advances of Carbon-Based Nano Zero Valent Iron for Heavy Metals Remediation in Soil and Water: A Critical Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 426, 127993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Rehman, F.; Rafeeq, H.; Waqas, M.; Asghar, A.; Afsheen, N.; Rahdar, A.; Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. In-Situ, Ex-Situ, and Nano-Remediation Strategies to Treat Polluted Soil, Water, and Air—A Review. Chemosphere 2022, 289, 133252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Han, Y.; Duan, Y.; Lai, X.; Fu, R.; Liu, S.; Leong, K.H.; Tu, Y.; Zhou, L. Review on the Contamination and Remediation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Coastal Soil and Sediments. Environ. Res. 2022, 205, 112423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wells, M.; Niazi, N.K.; Bolan, N.; Shaheen, S.; Hou, D.; Gao, B.; Wang, H.; Rinklebe, J.; Wang, Z. Nanobiochar-Rhizosphere Interactions: Implications for the Remediation of Heavy-Metal Contaminated Soils. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 299, 118810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambaye, T.G.; Chebbi, A.; Formicola, F.; Prasad, S.; Gomez, F.H.; Franzetti, A.; Vaccari, M. Remediation of Soil Polluted with Petroleum Hydrocarbons and Its Reuse for Agriculture: Recent Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives. Chemosphere 2022, 293, 133572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markandeya; Mohan, D.; Shukla, S.P. Hazardous Consequences of Textile Mill Effluents on Soil and Their Remediation Approaches. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 7, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahithya, K.; Mouli, T.; Biswas, A.; Mercy, S.T. Remediation Potential of Mushrooms and Their Spent Substrate against Environmental Contaminants: An Overview. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 42, 102323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshreshtha, S. Removal of Pollutants Using Spent Mushrooms Substrates. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 833–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menaga, D.; Rajakumar, S.; Ayyasamy, P.M. Spent Mushroom Substrate: A Crucial Biosorbent for the Removal of Ferrous Iron from Groundwater. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, S.N.; Redington, W.; Holland, L.B. Remediation of Metal Contaminated Simulated Acid Mine Drainage Using a Lab-Scale Spent Mushroom Substrate Wetland. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Tiwari, A.; Rathore, H.; Prasad, S.; Hariprasad, P.; Sharma, S. Valorization of Paddy Straw Using De-Oiled Cakes for P. ostreatus Cultivation and Utilization of Spent Mushroom Substrate for Biopesticide Development. Waste Biomass Valor. 2021, 12, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umor, N.A.; Ismail, S.; Abdullah, S.; Huzaifah, M.H.R.; Huzir, N.M.; Mahmood, N.A.N.; Zahrim, A.Y. Zero Waste Management of Spent Mushroom Compost. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2021, 23, 1726–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seekram, P.; Thammasittirong, A.; Thammasittirong, S.N.-R. Evaluation of Spent Mushroom Substrate after Cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus as a New Raw Material for Xylooligosaccharides Production Using Crude Xylanases from Aspergillus Flavus KUB2. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, T.; Lin, X. Influence of Organic Amendments Used for Benz[a]Anthracene Remediation in a Farmland Soil: Pollutant Distribution and Bacterial Changes. J. Soils Sedim. 2020, 20, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ge, W.; Zhang, X.; Chai, C.; Wu, J.; Xiang, D.; Chen, X. Biodegradation of Aged Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Agricultural Soil by Paracoccus Sp. LXC Combined with Humic Acid and Spent Mushroom Substrate. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 379, 120820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, Y.K.; Ma, T.-W.; Chang, J.-S.; Yang, F.-C. Recent Advances and Future Directions on the Valorization of Spent Mushroom Substrate (SMS): A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajavat, A.S.; Mageshwaran, V.; Bharadwaj, A.; Tripathi, S.; Pandiyan, K. Spent Mushroom Waste: An Emerging Bio-Fertilizer for Improving Soil Health and Plant Productivity. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 345–354. ISBN 978-0-323-85579-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Tan, H.; Liu, H.; Wu, B.; Xu, F.; Xu, H. A Nanoscale Ferroferric Oxide Coated Biochar Derived from Mushroom Waste to Rapidly Remove Cr(VI) and Mechanism Study. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 7, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wu, B.; Xu, H. Fe3O4 Nanoparticle-Coated Mushroom Source Biomaterial for Cr(VI) Polluted Liquid Treatment and Mechanism Research. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 171776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sriramulu, M.; Sumathi, S. Biosynthesis of Palladium Nanoparticles Using Saccharomyces cerevisiae Extract and Its Photocatalytic Degradation Behaviour. Adv. Nat. Sci: Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 9, 025018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, B.; Ray, J.; Jana, S.; Bhanja, S.K.; Tripathy, T. In Situ Preparation of Tricholoma Mushroom Polysaccharide-g-Poly(N,N-Dimethyl Acrylamide-Co-Acrylic Acid)–CuO Composite Nanoparticles for Highly Sensitive and Selective Sensing of Th 4+ in Aqueous Medium. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 19707–19719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sithole, S.C.; Agboola, O.O.; Mugivhisa, L.L.; Amoo, S.O.; Olowoyo, J.O. Elemental Concentration of Heavy Metals in Oyster Mushrooms Grown on Mine Polluted Soils in Pretoria, South Africa. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 101763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, S.C.; Peng, W.X.; Yang, Y.; Ge, S.B.; Soon, C.F.; Ma, N.L.; Sonne, C. Development of Formaldehyde-Free Bio-Board Produced from Mushroom Mycelium and Substrate Waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 400, 123296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, K.; Dong, L.; Qian, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J. Manganese Oxide-Modified Biochar Derived from Discarded Mushroom-Stick for the Removal of Sb(III) from Aqueous Solution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iravani, S. Bacteria in Nanoparticle Synthesis: Current Status and Future Prospects. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2014, 2014, e359316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Das, B.S.; Das, A.; Mishra, A.; Arakha, M. Microbial Cells as Biological Factory for Nanoparticle Synthesis. Front. Mater. Sci. 2021, 15, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, D.; Nag, M.; Sheikh, H.I.; Sarkar, T.; Edinur, H.A.; Pati, S.; Ray, R.R. Microbiologically-Synthesized Nanoparticles and Their Role in Silencing the Biofilm Signaling Cascade. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Ramady, H.; Abdalla, N.; Fawzy, Z.; Badgar, K.; Llanaj, X.; Törős, G.; Hajdú, P.; Eid, Y.; Prokisch, J. Green Biotechnology of Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus L.): A Sustainable Strategy for Myco-Remediation and Bio-Fermentation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, A.; Katerina, R. Biology, Cultivation and Applications of Mushrooms; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Goal (SDG) | The Expected Role of Soil | The Goal (SDG) | The Expected Role of Soil |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 1 | Indirect role of soil, which may can support reducing the poverty if this soil well be perfect used (*) | SDG 9 | Direct and indirect role of soil in the industry. Soil has direct role for the infrastructure and fostering innovation is needed (*) |

| SDG 2 | Indirect and/or direct role of soil, which is the main source for our foods. Healthy soil provides us with healthy food to reduce malnutrition (*) | SDG 10 | Without caring for soil and its conservation, the income of several populations will be not able to grow faster, especially for farmers |

| SDG 3 | Indirect and/or direct role of soil, the nutritional status of which is the main control for our health, including the positive and negative sides (*) | SDG 11 | Indirect role of soil for sustaining life in rural and urban areas. Soil or land is a guarantee for affordable and safe housing (*) |

| SDG 4 | Indirect role of soil, which needs more interest and to be added to inclusive, equitable quality education | SDG 12 | Soil has direct and indirect impacts on the environment by the self-management of the global wastes and their recycling in an eco-friendly way (*) |

| SDG 5 | For soil and its handling, everyone should respect and conserve soils. Soils does not differ between man and woman, and all can support it | SDG 13 | Soil has an indirect impact on climate and its changes by regulating emissions from soil and promoting renewable energy (*) |

| SDG 6 | Direct and indirect role of soil in providing clean water. Clean water is needed for protecting people from diseases (*) | SDG 14 | Indirect role of soil/land for conserving and sustainably using the seas, oceans, and different marine resources |

| SDG 7 | Indirect role for soil for saving energy. By 2030, more renewable, affordable energy sources are needed (*) | SDG 15 | For a prosperous world, soil and/or land need to stop any kind of degradation and must preserve ecosystems of forests, deserts, and mountains (*) |

| SDG 8 | Indirect role of soil for highly sustainable economic growth. There is no successful economy without sustaining and conserving soil | SDG 16 | Indirect impacts of soil/land on societies and their institutions. Soil/land may control the peace and justice for all people |

| Item | Champignon | Oyster Mushrooms | Shiitake Mushrooms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom | Fungi | Fungi | Fungi |

| Phylum | Basidiomycota | Basidiomycota | Basidiomycota |

| Class | Agaricomycetes | Agaricomycetes | Agaricomycetes |

| Order | Agaricales | Agaricales | Agaricales |

| Family | Agaricaceae | Pleurotaceae | Omphalotaceae |

| Genus | Agaricus (200 species) | Pleurotus (202 species) | Lentinula (9 species) |

| Example | Agaricus Linnaeus L. | Pleurotus ostreatus L. | Lentinula edodes L. |

|  |  | |

| Agaricus campestris | Pleurotus ostreatus | Lentinula edodes | |

| Some common mushroom species of the family | |||

| Agaricus abruptibulbus Peck 1905 | Pleurotus calyptratus Sacc. 1887 | Lentinula edodes (Berk.) Pegler (1976) | |

| Agaricus amicosus Kerrigan 1989 | P. citrinopileatus Singer 1942 | Lentinula edodes (Beck.) Sing. (1941) | |

| Agaricus arvensis Schaeff. 1774 | P. cornucopiae (Paulet) Rolland 1910 | Lentinula aciculospora J.L. Mata & R.H. Petersen (2000) | |

| Agaricus augustus Fr. 1838 | P. columbinus Quél. 1881 | Lentinula boryana (Berk. & Mont.) Pegler (1976) | |

| A. bitorquis (Quél.) Sacc. 1887 | P. cystidiosus O.K. Mill. 1969 (edible) | Lentinula guarapiensis (Speg.) Pegler (1983) | |

| A. bisporus (Lange) Imbach 1946 | P. dryinus (Pers.) P.Kumm. 1871 | Lentinula lateritia (Berk.) Pegler (1983) | |

| Agaricus blazei Murrill 1945 | P. djamor (Rumph. ex Fr.) Boedijn 1959 | Lentinula raphanica (Murrill) Mata & R.H. Petersen (2001) | |

| Agaricus campestris L. 1753 | P. eryngii (DC.) Quél. 1872 | Lentinula reticeps (Mont.) Murrill (1915) | |

| A. columellatus (Long) R. Chapm., V.S. Evenson, and S.T. Bates 2016 | P. opuntiae (Durieu and Lév.) Sacc. 1887 | Lentinula novae-zelandiae (G.Stev.) Pegler (1983) | |

| A. cupreobrunneus (Jul. Schäff. and Steer) Pilát 1951 | P. pulmonarius (Fr.) Quél. 1872 | ||

| Agaricus sylvaticus Schaeff. 1774 | Pleurotus radicosus Pat. 1917 | ||

| Cultivated Plant or Used Mushroom for SMS | Soil Properties or Used Substrate | Main Purpose of the Application | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. Applied SMS under cultivated soils | |||

| Paddy rice (Oryza sativa L.) | Silty loam, pH (5.58), SOM (1.2 g kg−1), and Cd (72.87 mg kg−1) | SMS of both P. eryngii and A. bisporus decreased soil content of Cd by 99% and increased rice yield by 38.8% | [100] |

| Roselle (Hibiscus sabdarifa L.) | Loamy sand, pH (7.98), SOM (0.25%) | Applied SMS to improve plant growth, soil fertility, and its quality as a biofertilizer | [101] |

| Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) | Silty, pH (6.12), TOC (11.1 g kg−1) | SMS enhanced soil microbial diversity and the activity of enzymes for long-term cultivated cucumber in greenhouse | [102] |

| Barely (Hordeum vulgare L.) | Clayey, pH (5.40), initial soil 60 kg N ha−1 and fertilized up to 200 kg N ha−1 | Applied SMS (50%) caused a strong shift in soil-rhizosphere microbiota due to release enzymes as root exudates, depending on the kind of applied organic fertilizers | [103] |

| Pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo ssp.) | Sandy loam, pH (8.0), N (6.0 mg kg−1) | Applied SMS as organic fertilizer is promising under organic farming | [104] |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) | Modified paddy straw as substrate | Paddy straw based-silica rich SMS of P. ostreatus is effective for plant disease and nutrient management | [105] |

| Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) | Composted SMS, vermiculite, coir, and perlite at (3:1:1:1) | Microbial agents can inhibit potentially pathogenic microbes of plants and increase the efficient utilization of SMS | [106] |

| Cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum Mill.) | Soil (dystro-ferric red latosol) | Co-cultivation at the same bucket tomato and A. bisporus reduced by 60 days and continuous producing mushroom prolonged by 120 days | [107] |

| II. Applied SMS under non-cultivated soils | |||

| SMS provided by Xiangfang edible fungi factory, Harbin, China | Sandy, pH (6.83), SOM (38.64 g kg−1) | SMS was compared to biochar and lime on reducing Cd-bioavailability by 66.47% and increased soil enzyme activities | [108] |

| Organic amendment (SMS and its biochar) | Soil pH (6.83), SOM (38.64 g kg−1), ava. N (115.7 mg kg−1) | Applied amendment alleviated Cd and N damage on soil, by increasing microbial biomass and enzyme activities in the soil | [109] |

| SMS-derived biochar | Soil pH (4.62), TOC and TN (57.2 and 3.9 g kg−1, resp.) | Spent mushroom substrate derived biochar was pyrolyzed at 450 °C can mitigate greenhouse gas emissions | [110] |

| Applied SMS, bacteria of Paracoccus sp., and humic acid | PAHs in soil was 1.97 mg kg−1, soil pH (6.71) | Bio-degradation of PAHs by humic acid and SMS via soil laccase activity as bioremediation | [111] |

| Mushroom Species | Nanoparticle Kind and Its Size (nm) | Bioactivity or the Reaction | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agaricus bisporus | Ag-NPs (80–100) | Antibacterial activities | [153] |

| Amanita muscaria | Ag-NPs (5–25) | Anticancer activity | [153] |

| Pleurotus ostreatus | Ag-NPs (35) | Antioxidant properties | [154] |

| Pleurotus giganteus | Ag-NPs (5–25) | Antimicrobial activity | [155] |

| Ganoderma applanatum | Ag-NPs (20–5) | Antioxidant; Antibacterial | [156] |

| Ganoderma lucidum | Ag-NPs (15–22) | Antimicrobial activity | [148] |

| Pleurotus giganteus | Ag-NPs (2–20) | Antibacterial activity | [155] |

| Lentinus tuber-regium | Ag-NPs (5–35) | Antimicrobial activity | [157] |

| Pleurotus ostreatus | Ag-NPs (15–45) | Antimicrobial activity | [158] |

| Pichia pastoris | Ag-NPs (6.63) | Antioxidant and antimicrobial | [159] |

| Inonotus hispidus | Ag-NPs (69.24) | Antibacterial and antifungal | [150] |

| Ramaria botrytis | Ag@AuNPs (200) | Antioxidant and antibacterial | [149] |

| Flammulina velutipes | Ag-NPs (22) | Antibacterial activities | [160] |

| Boletus edulis Coriolus versicolor | Ag-NPs (87.7) Ag-NPs (86.0) | Anticancer of breast, colon; liver, and antimicrobial | [137] |

| Pleurotus ostreatus Pleurotus djamor | Ag-NPs (28.44) Ag-NPs (55.76) | Antioxidant activities and antimicrobial agent | [152] |

| Agaricus arvensis | Ag-NPs (20) | Anticancer, Antimicrobial | [138] |

| Ganoderma lucidum | Ag-NPs (50) | Antibacterial activities | [140] |

| Agaricus bisporus | Ag-NPs (50.44) | Antibacterial activity | [139] |

| Pleurotus sajor-caju | Au-NPs (16–18) | Cancer cell inhibition | [135] |

| Ganoderma applanatum | Au-NPs (18.7) | Dye decolorization | [161] |

| Lentinula edodes | Au-NPs (5–15) | Anticancer activity | [162] |

| Ganoderma lucidium | Au-NPs (5–15) | Anticancer activity | [162] |

| Agaricus bisporus | Cu-NPs (10) | Antibactericidal activity | [143] |

| Pleurotus tuber-regium | Se-NPs (50) | Anticancer activity | [163] |

| Pleurotus djamor | TiO2-NPs (31) | Antilarval properties | [142] |

| Pleurotuss ostreatu | ZnS-NPs (2–5) | Biomedical; food packaging | [164] |

| Agaricus bisporus | Zn-NPs (12–17) | Antirenal cancer | [165] |

| Candida albicans | ZnO-NPs (10.2) | Antimicrobial activities | [145] |

| Pleurotus floridanus | ZnO-NPs (34.98) | Biomedical applications | [144] |

| Pleurotus djamor | ZnO-NPs (38.73) | Antibacterial and anticancer | [166] |

| Agarius bisporus | ZnO-NPs (20) | Antibacterial activity | [167] |

| Mushroom Species | Potential Materials | The Main Application/Main Findings | Refs. |

| Agaricus bisporus | Nanoencapsulation of rutin in β-glucan matrix | Encapsulation by green technology for nutraceutical activities | [147] |

| Lentinula edodes | Chitin/cellulose nanofiber | Growth promotion and disease resistance | [170] |

| Lentinula edodes, Pleurotus ostreatus | Chitin nanopaper derived from mushroom | Extraction of chitin from the mushrooms to produce nanopaper | [171] |

| Pleurotus ostreatus | Chitin–glucan complex | Producing eco-friendly polymers | [172] |

| Agaricus bisporus, Pleurotus ostreatus | Biocompatible fluorescent carbon-based nanomaterials | Producing live cells by fluorescent carbon quantum dot derived from mushrooms | [173] |

| Lentinus edodes | Nanoemulsion | Nanoemulsion derived from mushroom polysaccharide for the antitumor activity | [174] |

| Agaricus bisporus | Chitin nanopaper derived from mushroom | Production of chitin nanopaper from an extract of mushrooms | [175] |

| Agaricus bisporus | Fraction of chitin/glucan | Producing glycosidases (e.g., chitinases), which immobilize on nanoparticles and spray for biocontrol of insect pests | [176] |

| Lactarius volemus | Modified chitosan with nano-Fe3O4 nanoparticles | Purification of phytase enzymes and their potential in cereal industries | [177] |

| Lentinus edodes | Cellulose nanofibers | The highest yield of the film was produced using 0.18 g NaClO per 1.0 g of waste mushroom bed (71% cellulose) | [178] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elsakhawy, T.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Abowaly, M.; El-Ramady, H.; Badgar, K.; Llanaj, X.; Törős, G.; Hajdú, P.; Prokisch, J. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles by Mushrooms: A Crucial Dimension for Sustainable Soil Management. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074328

Elsakhawy T, Omara AE-D, Abowaly M, El-Ramady H, Badgar K, Llanaj X, Törős G, Hajdú P, Prokisch J. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles by Mushrooms: A Crucial Dimension for Sustainable Soil Management. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):4328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074328

Chicago/Turabian StyleElsakhawy, Tamer, Alaa El-Dein Omara, Mohamed Abowaly, Hassan El-Ramady, Khandsuren Badgar, Xhensila Llanaj, Gréta Törős, Peter Hajdú, and József Prokisch. 2022. "Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles by Mushrooms: A Crucial Dimension for Sustainable Soil Management" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 4328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074328

APA StyleElsakhawy, T., Omara, A. E.-D., Abowaly, M., El-Ramady, H., Badgar, K., Llanaj, X., Törős, G., Hajdú, P., & Prokisch, J. (2022). Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles by Mushrooms: A Crucial Dimension for Sustainable Soil Management. Sustainability, 14(7), 4328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074328