Host Population Well-Being through Community-Based Tourism and Local Control: Issues and Ways Forward

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Community-Based Tourism

4. Well-Being

- (1)

- basic material for a good life (economic);

- (2)

- health (medical);

- (3)

- good social relations (social);

- (4)

- security (social and political);

- (5)

- freedom of choice and action (social and political).

- doing well means feeling good, characteristic of Western societies;

- doing good means feeling well, found in developing countries.

5. Discussion: Proposing a CBT Well-Being Relationship

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mendes, S.; Martins, J.; Mouga, T. Ecotourism based on the observation of sea turtles—A sustainable solution for the touristic promotion of São Tomé and Príncipe. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.; Kabu, M.; Lobang, S. Development of Community-Based Tourism Monbang Village—Alor, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Engineering, Science, and Commerce, ICESC 2019, Labuan Bajo, Nusa Tenggara Timur, Indonesia, 18–19 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baker, D.M.; Taylor, M.; Jiang, L. Local residents’ attitudes toward the impacts of tourism development in the Caribbean nation of St. Kitts & Nevis. Revista de Turism—Studii si Cercetari in Turism 2019, 28. Available online: http://www.revistadeturism.ro/rdt/article/view/437 (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Giampiccoli, A. A conceptual justification and a strategy to advance community-based tourism development. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Mtapuri, O. Towards a coalescence of the community-based tourism and ‘Albergo Difusso’ tourism models for Sustainable Local Economic Development. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2020, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dłużewska, A.; Giampiccoli, A. Enhancing island tourism’s local benefits: A proposed community-based tourism-oriented general model. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Wang, Y.; Jin, M. Livelihood sustainability in a rural tourism destination—Hetu Town, Anhui Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. Beyond growth thinking: The need to revisit sustainable development in tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.V.; de Man, F. Tourism, inclusive growth and decent work: A political economy critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, S. International trade in services and inequalities: Empirical evaluation and role of tourism services. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Y.A.; McLees, L.A. Space, ownership and inequality: Economic development and tourism in the highlands of Lesotho. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2012, 5, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J. The roles of sustainable tourism in neoliberal policies and poverty reduction strategies: Do they adequately address quality of life? Appl. Anthropol. 2011, 31, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Carnicelli, S.; Krolikowski, C.; Wijesinghe, G.; Boluk, K. Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1926–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C.; Timothy, D.J.; Öztürk, Y. Tourism growth, national development and regional inequality in Turkey. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 133–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinyondo, A.; Pelizzo, R. Tourism, development and inequality: The case of Tanzania. Poverty Public Policy 2015, 7, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-García, M.A.; González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Vega-Vázquez, M.V. Does Sun-and-Sea All-Inclusive Tourism Contribute to Poverty Alleviation and/or Income Inequality Reduction? The case of the Dominican Republic. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Cai, Z.; Zheng, J.; Wen, Y. Conservation, ecotourism, poverty, and income inequality—A case study of nature reserves in Qinling, China. World Dev. 2019, 115, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M. A Conceptual Framework for Identifying the Binding Constraints to Tourism-Driven Inclusive Growth. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tabosa, F.J.S.; Castelar De Carvalho, P.U.; Irffi, G. Brazil, 1981–2013: The Effects of Economic Growth and Income Inequality on Poverty, Revista CEPAL; Naciones Unidas Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL): Santiago, Chile, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L. The Relationship between Poverty and Inequality: Resource Constraint Mechanisms; Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Inequality Matters. Report of the World Social Situation; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Document ST/ESA/345. [Google Scholar]

- Saayman, M.; Giampiccoli, A. Community-based and pro-poor tourism: Initial assessment of their relation to community development. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 12, 145–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Hughes, E. Can tourism help to end poverty in all its forms everywhere? The challenge of tourism addressing SDG1. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1061–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.T.; Stone, L.S. Challenges of community-based tourism in Botswana: A review of literature. Trans. R. Soc. S. Afr. 2020, 75, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Eom, T.; Al-Ansi, A.; Ryu, H.B.; Kim, W. Community-based tourism as a sustainable direction in destination development: An empirical examination of visitor behaviors. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, L.; Hsu, M.K.; Boostrom, R.E., Jr. From recreation to responsibility: Increasing environmentally responsible behavior in tourism. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, K.; Andereck, K.; Vogt, C. Local residents’ perceptions about tourism development. Travel Tour. Res. Assoc. Adv. Tour. Res. Glob. 2019, 74, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dłużewska, A. The influence of the localization of tourist facilities on the dysfunction of tourism discussed on the example of southern Tunisia. In Naturbanization. New Identities and Process for Rural-Natural Areas; Prados, M.J., Ed.; CRC, Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus, L. Gaining Community Support for Tourism in Rural Areas in Portugal. In Communities as a Part of Sustainable Rural Tourism—Success Factor or Inevitable Burden? Proceedings of the Community Tourism Conference, Kotka, Finland, 10–11 September 2013; Lähdesmäki, M., Matilainen, A., Eds.; Ruralia Institute: Mikkeli, Finland, 2013; pp. 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chassagne, N.; Everingham, P. Buen Vivir: Degrowing extractivism and growing wellbeing through tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1909–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jiang, J.; Li, S. A Sustainable Tourism Policy Research Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lv, Q.; Xie, X.; Li, Y. The Effects of Resident Empowerment on Intention to Participate in Financing: The Roles of Personal Economic Benefit and Negative Impacts of Tourism. J. China Tour. Res. 2019, 15, 541–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca-Rodríguez, C.M.; Casas-Jurado, A.C.; García-Fernández, R.M. Tourism and poverty alleviation: An empirical analysis using panel data on Peru’s departments. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 19, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, A.; Mertens, F. Participatory management of community-based tourism: A network perspective. Community Dev. 2017, 48, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarjuna, G. Local Community Involvement in Tourism: A Content Analysis of Websites of Wildlife Resorts. Atna J. Tour. Stud. 2015, 10, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Salleh, N.H.M.; Shukor, M.S.; Othman, R.; Samsudin, M.; Idris, S.H.M. Factors of Local Community Participation in Tourism-Related Business: Case of Langkawi Island. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2016, 6, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEF. The Inclusive Development Index 2018 Summary and Data Highlights; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Inclusive Tourism Destinations Model and Success Stories; World Tourism Organisation: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Justice tourism and alternative globalisation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neth, B.; Ol Rith, S.; Knerr, B. Global environmental governance and politics of ecotourism: Case study of Cambodia. In Proceedings of the 12th EADI General Conference, Geneva, Switzerland, 24–28 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, R.; Neves, K. Contradictions in Tourism. The Promise and Pitfalls of Ecotourism as a Manifold Capitalist Fix 2012. Environ. Soc. Adv. Res. 2012, 3, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duffy, R. Nature-based tourism and neoliberalism: Concealing contradictions. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.S.; Semrad, K.J.; Yilmaz, S.S. Community Based Tourism Finding the Equilibrium in COMCEC Context: Setting the Pathway for the Future; COMCEC Coordination Office: Ankara, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Miedes-Ugarte, B.; Flores-Ruiz, D.; Wanner, P. Managing Tourist Destinations According to the Principles of the Social Economy: The Case of the Les Oiseaux de Passage Cooperative Platform. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearns, K. Community-based tourism and peace parks benefit local communities through conservation in Southern Africa. Acta Acad. 2012, 44, 70–87. [Google Scholar]

- Giampiccoli, A. Community-based tourism: Origins and present trends. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2015, 21, 675–687. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, K.X.H.; Segui, A.E. Experiences of community-based tourism in Romania: Chances and challenges. J. Tour. Anal. 2020, 27, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, R.E.; Reid, D.G. Community integration. Island Tourism in Perú. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juma, L.O.; Khademi-Vidra, A. Community-Based Tourism and Sustainable Development of Rural Regions in Kenya; Perceptions of the Citizenry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaur, P.; Jawaid, A.; Bt Abu Othman, N. The Impact of Community Based Tourism On Community Development In Sarawak. J. Borneo Kalimantan 2016, 2, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dangi, T.B.; Jamal, T. An Integrated Approach to Sustainable Community-Based Tourism. Sustainability 2008, 8, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sofield, T.H.B. Empowerment for Sustainable Tourism Development; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- George, B.P.; Nedelea, A.; Antony, M. The business of community based tourism: A multi-stakeholder approach. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 3. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1267159 (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Amat Ramsa, Y.; Mohd, A. Community-based Ecotourism: A New proposition for Sustainable Development and Environmental Conservation in Malaysia. J. Appl. Sci. 2004, 4, 583–589. [Google Scholar]

- Leksakundilok, A.; Hirsch, P. Community-Based Tourism in Thailand. In Tourism at the Grassroot. Villagers and Visitors in the Asia-Pacific; Connell, J., Rugendyke, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 214–235. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Castillo-Canalejo, A.M. Community-based island tourism: The case of Boa Vista in Cape Verde. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2014, 8, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höckert, E. Sociocultural Sustainability of Rural Community-Based Tourism. Case Study of Local Participation in Fair Trade Coffee Trail, Nicaragua; Lapland University Press: Rovaniemi, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Strydom, A.J.; Mangope, D.; Henama, U.S. Making community-based tourism sustainable: Evidence from the Free State province, South Africa. GeoJournal Tour. Geosites 2019, XII, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Guijarro, G.; Pacheco, V.; Verdesoto, J.F. Percepciones y sostenibilidad del turismo comunitario: Comunidad Shiripuno. Misahuallí—Ecuador. Antropol. Cuad. Investig. 2018, 19, 12–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, M.J.; Hall, M.C.; Lindo, P.; Vanderschaeghe, M. Can community-based tourism contribute to development and poverty alleviation? Lessons from Nicaragua. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 14, 725–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Saayman, M. Community-based tourism development model and community participation. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2018, 7, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, E. A Community-Based Tourism Model: Its Conception and Use. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Tourism and community development issues. In Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2002; pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ullan de La Rosa, F.J.; Aledo Tur, A.; Garcia Andreu, H. Community-Based Tourism and the Political Instrumentalization of the Concept of Community. A New Theoretical Approach and an Ethnographical Case Study in Northeastern Brazil. Anthropos 2017, 112, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nuzhar, S. Influencing Community-Based Tourism Empirical Study on Sylhet Region. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 18, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avan, A.; Zorlu, Ö. Community Based Tourism Activities within the Context of Sustainability of Tourism: A Case of Gelemiş Village. In Proceedings of the 1st International Sustainable Tourism Congress, Kastamonu, Turkey, 23–25 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sproule, K.W.; Suhandi, A.S. Guidelines for Community-Based Ecotourism Programs: Lessons from Indonesia. In Ecotourism: A Guide for Planners and Managers; Lindberg, K., Epler Wood, M., Engeldrum, D., Eds.; The Ecotourism Society, Willey: North Bennington, VT, USA, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 215–235. [Google Scholar]

- Ndlovu, N.; Rogerson, C.M. The Local Economic Impacts of Rural Community-Based Tourism in Eastern Cape. In Tourism and Development Issues in Contemporary South Africa; Rogerson, C.M., Visser, G., Eds.; Africa Institute of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2004; pp. 436–451. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, L.K. Ecology, Environment and Tourism; ESHA Books: Delhi, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Suansri, P. Community Based Tourism Handbook. Responsible Ecological Social Tour (REST); Responsible Ecological Social Tour-REST: Bangkok, Thailand, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.E.; Eagles, P.F.J. An Integrative Approach to Tourism: Lessons from the Andes of Peru. J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dłużewska, A. Wellbeing–Conceptual Background and Research Practices. Društvena Istraživanja 2016, 25, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shea, W.R. Introduction: The Quest for a High Quality of Life. In Values and the Quality of Life; Shea, W.R., King-Farlow, J., Eds.; Science History Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1976; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Challenges of sustainable tourism development process in the developing world: The case of Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Paramati, S.R. The impact of tourism on income inequality in developing economies: Does Kuznets curve hypothesis exist? Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Britton, S.G. The political economy of tourism in the Third World. Ann. Tour. Res. 1982, 9, 331–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, S.G.; Clarke, W.C. Tourism in small developing countries. In Ambiguous Alternative: Tourism in Small Developing Countries; University of South Pacific: Suva, Fiji, 1987; pp. 167–194. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, C. Roots of unsustainable tourism development at the local level: The case of Urgup in Turkey. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Expected level of community participation in the tourism development process. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, J.S. Neo-Colonialism, Dependency and External Control of Africa’s Tourism Industry. In Akama JS Tourism and Postcolonialism: Contested Discourses, Identities and Representations; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 140–152. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Well-being, agency and freedom: The Dewey lectures 1984. J. Philos. 1985, 82, 169–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, R.A.; Eckersley, R.; Pallant, J.; Van Vugt, J.; Misajon, R. Developing a national index of subjective wellbeing: The Australian Unity Wellbeing Index. Soc. Indic. Res. 2003, 64, 159–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. A value based index for measuring national quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res. 1995, 36, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R.A.; Denby, L.; McGill, R.; Wilks, A.R. Analysis of data from the Places Rated Almanac. Am. Stat. 1987, 41, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: A Framework for Assessment. In Millennium Ecosystem Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis/Current State and Trends/Scenarios/Policy responses/Multiscale Assessments. In Millennium Ecosystem Assessment; Island Press: Washington DC, USA, 2005.

- Lee, S.E. Education as a Human Right in the 21st Century. Democr. Educ. 2013, 21, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, F.M.; Withey, S.B. Social Indicators of Well-Being: American’s Perceptions of Life Quality; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, A.P.E.; Converse Rodgers, W.L. The Quality of American Life: Perceptions, Evaluations, and Satisfactions; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M. Measuring quality of life: Economic, social and subjective indicators. Soc. Indic. Res. 1996, 40, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, D. Quality of Life in Health Care and Medical Ethics. In The Quality of Life; Nussbuam, M., Sen, A., Eds.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 95–132. [Google Scholar]

- Land, K.C. Social indicators and the quality of life: Where do we stand in the mid 1990s? SINET 1996, 45, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, A.S. Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, R.A.; Nistico, H. Maintaining life satisfaction: The role of positive cognitive bias. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 37–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R. Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? Some Empirical Evidence. In Nations and Households in Economic Growth; David, P.A., Reder, M.W., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 89–125. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin, R. Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1995, 27, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copestake, J.; Campfield, L. Measuring Subjective Wellbeing in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Peru and Thailand using a Personal Life Goal Satisfaction Approach; WeD Working Paper; University of Bath: Bath, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- White, S. Analysing Wellbeing: A Framework for Development Practice; WeD Working Paper; University of Bath: Bath, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Peake, R. Swahili Stratification and Tourism in Malindi Old Town, Kenya. Africa 1989, 59, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dłużewska, A. Well-being versus sustainable development in tourism—The host perspective. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 27, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, P.; Novelli, M. (Eds.) Tourism Development: Growth, Myths and Inequalities; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fredline, L.; Deery, M.; Jago, L. Social Impacts of Tourism on Communities; CRC for Sustainable Tourism: Gold Coast, QLD, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, R.; Griffin, K.A. (Eds.) Conflicts, Religion and Culture in Tourism; CABI: Wallingfort, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Haley, A.J.; Snaith, T.; Miller, G. The social impacts of tourism: A case study of Bath, UK. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 647–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrill, R. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: A literature review with implications for tourism planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2004, 18, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurowski, C.; Gursoy, D. Distance effects on residents’ attitudes toward tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Dyer, P.; Carter, J.; Gursoy, D. Exploring residents’ perceptions of the social impacts of tourism on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2008, 9, 288–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diedrich, A.; Garcia-Buades, E. Local perceptions of tourism as indicators of destination decline. Tour. Manag. 2008, 41, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Murray, I. Resident attitudes towards sustainable community tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deery, M.; Fredline, L.; Jago, L. A framework for the development of social and socio-economic indicators for sustainable tourism in communities. Tour. Rev. Int. 2005, 9, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Jurowski, C.; Uysal, M. Resident attitudes: A structural modeling approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pfister, R. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism and perceived personal benefits in a rural community. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.; Norman, W.; Ying, T. Exploring the theoretical framework of emotional solidarity between residents and tourists. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.; Valentine, K.; Vogt, C.; Knopf, R. Across-cultural analysis of tourism and quality of life perceptions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dłużewska, A. Społeczno-Kulturowe Dysfunkcje Turystyczne w Krajach Islamu; Warsaw University Press: Warsaw, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Andriotis, K. Community groups’ perceptions of and preferences for tourism development: Evidence from Crete. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2005, 29, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S.; Punzo, L.F. Tourist development and host–guest interaction: An economic exchange theory. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Zátori, A. Rethinking Host–Guest Relationships in the Context of Urban Ethnic Tourism. In Reinventing the Local in Tourism; Channel View: Clevedon, UK, 2016; pp. 129–150. Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.21832/9781845415709/pdf#page=144 (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Smith, V.L. Hosts and guests revisited. Am. Behav. Sci. 1992, 36, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.; Severt, D. A triple lens measurement of host–guest perceptions for sustainable gaze in tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 711–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rheede, A.; Dekker, D.M. Hospitableness and sustainable development: New responsibilities and demands in the host-guest relationship. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 6, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yfantidou, G.; Matarazzo, M. The future of sustainable tourism in developing countries. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appadurai, A. The capacity to aspire. Culture and the Term of Recognition. In Cultural Politics in a Global Age Uncertainty, Solidarity and Innovation; Rao, V., Walton, M., Eds.; Oneworld Publications: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tsartas, P. Socioeconomic impacts of tourism on two Greek isles. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsartas, P. Tourism development in Greek insular and coastal areas: Sociocultural changes and crucial policy issues. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, H.; Boniface, P. (Eds.) Tourism and Cultural Conflicts; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pizam, A. Tourism’s Impacts; The social cost to the destination community as perceived by its residents. J. Travel Res. 1978, 16, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdu, T.; Hajdu, G. Are More Equal Societies Happier? Subjective Well-Being, Income Inequality, and Redistribution; IEHAS Discussion Papers No. MT-DP-2013/20; Institute of Economics, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, Hungarian Academy of Sciences Budapest: Budapest, Hungary, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chapple, S.; Förster, M.; Martin, J.P. Inequality and Well-Being in OECD Countries: What do we know? In Proceedings of the 3rd OECD World Forum on “Statistics, Knowledge and Policy”. Charting Progress, Building Visions, Improving Life, Busan, Korea, 27–30 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Szejnwald Brown, H.; Vergragt, P.J. From consumerism to wellbeing: Toward a cultural transition? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouf, K.A. Social Thoughts and Their Implications: Critically Analyse; iUniverse: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tasci, A.D.; Croes, R.; Villanueva, J.B. Rise and fall of community-based tourism—Facilitators, inhibitors and outcomes. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2014, 6, 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Baniya, R.; Shrestha, U.; Karn, M. Local and Community Well-Being through Community Based Tourism—A Study of Transformative Effect. J. Tour. Hosp. Educ. 2018, 8, 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Brohman, J. New Directions in Tourism for the Third World. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, T.P.; Sibiya, N.P.; Giampiccoli, A. Assessing local community participation in community-based tourism: The case of the Zulu-Mpophomeni Tourism Experience. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2018, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- ASEAN. ASEAN Community Based Tourism Standard; Cambodian Ministry of Tourism: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Häusler, N.; Strasdas, W. Training Manual for Community-Based Tourism; Went—Capacity Building International: Zschortau, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sakata, H.; Prideaux, B. An alternative approach to community-based ecotourism: A bottom-up locally initiated non-monetised project in Papua New Guinea. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 880–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

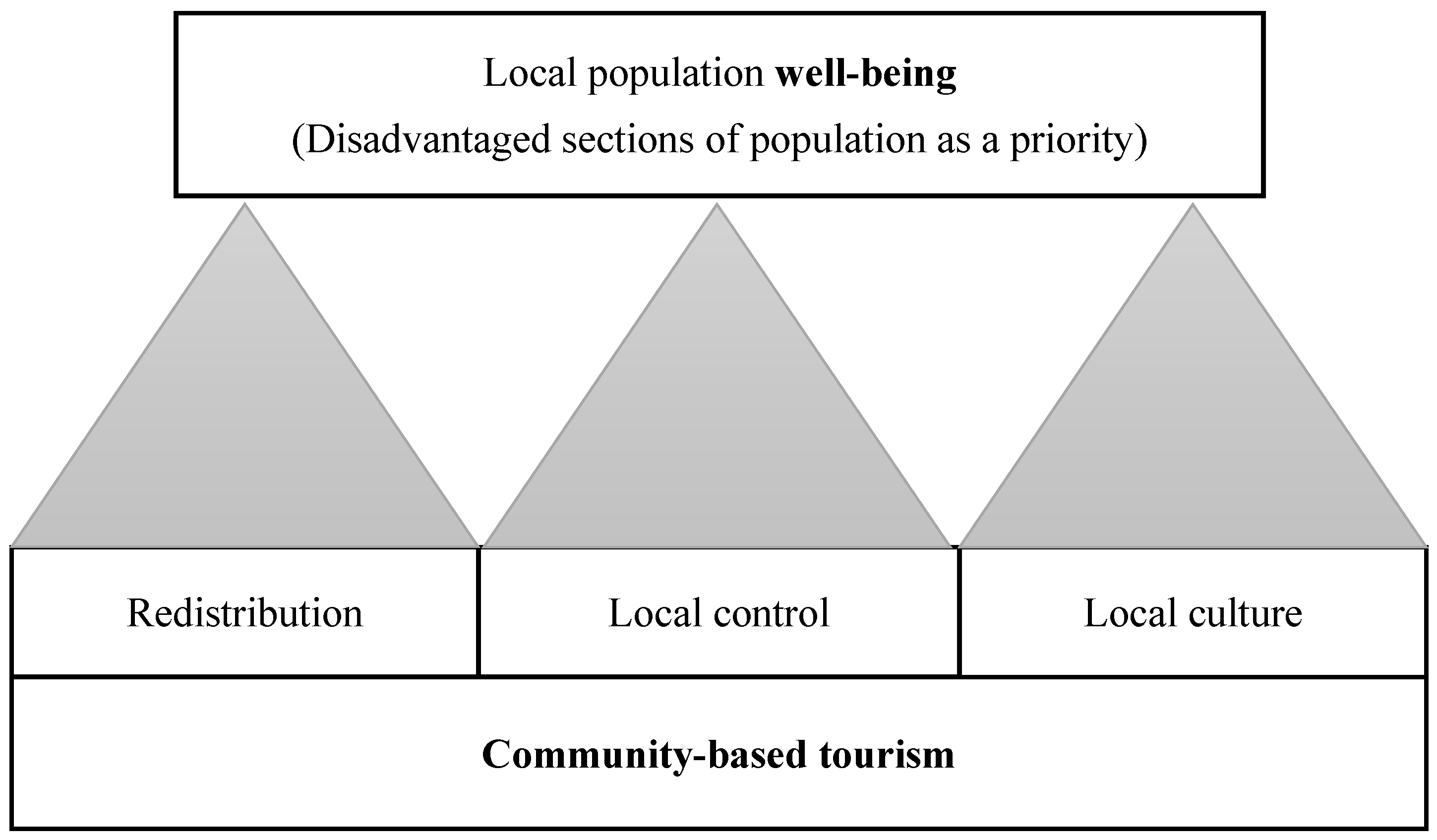

| Topic | Well-Being | CBT |

|---|---|---|

| Redistribution | √ | √ |

| Local control | √ | √ |

| Local culture | √ | √ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giampiccoli, A.; Dłużewska, A.; Mnguni, E.M. Host Population Well-Being through Community-Based Tourism and Local Control: Issues and Ways Forward. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074372

Giampiccoli A, Dłużewska A, Mnguni EM. Host Population Well-Being through Community-Based Tourism and Local Control: Issues and Ways Forward. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074372

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiampiccoli, Andrea, Anna Dłużewska, and Erasmus Mzobanzi Mnguni. 2022. "Host Population Well-Being through Community-Based Tourism and Local Control: Issues and Ways Forward" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074372