Tourism, Residents Agent Practice and Traditional Residential Landscapes at a Cultural Heritage Site: The Case Study of Hongcun Village, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Residential Landscapes in Traditional Villages and Tourism

2.2. Living Heritage as Landscape

3. Study Area and Research Methods

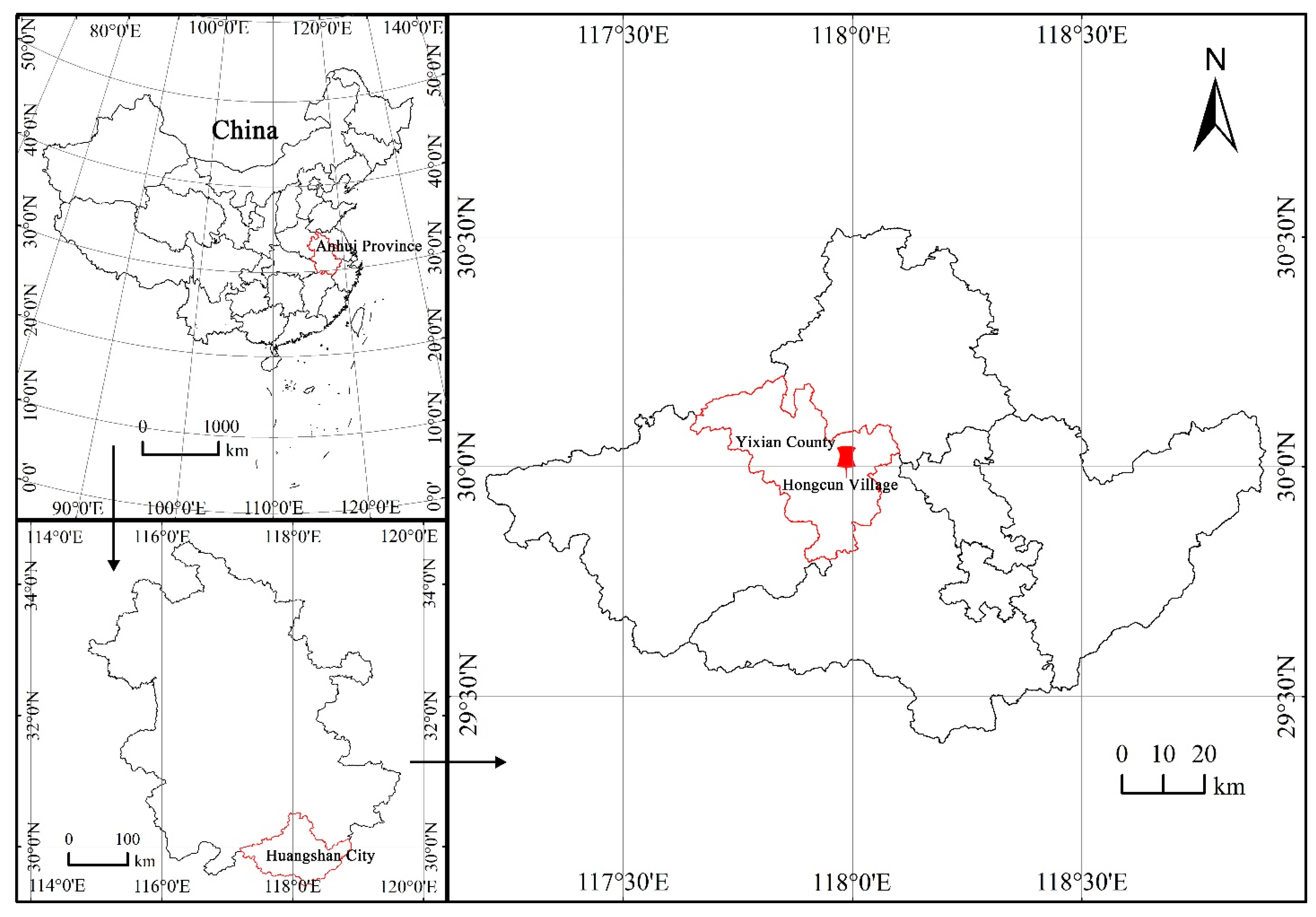

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Research Design and Data Collection

3.2.1. Non-Participatory Observations

3.2.2. In-Depth Interviews

3.2.3. Secondary Materials Analysis

4. Traditional Vernacular Houses in Hongcun: A Geographical Perspective

4.1. Foundation of Geographical Environment in Hongcun

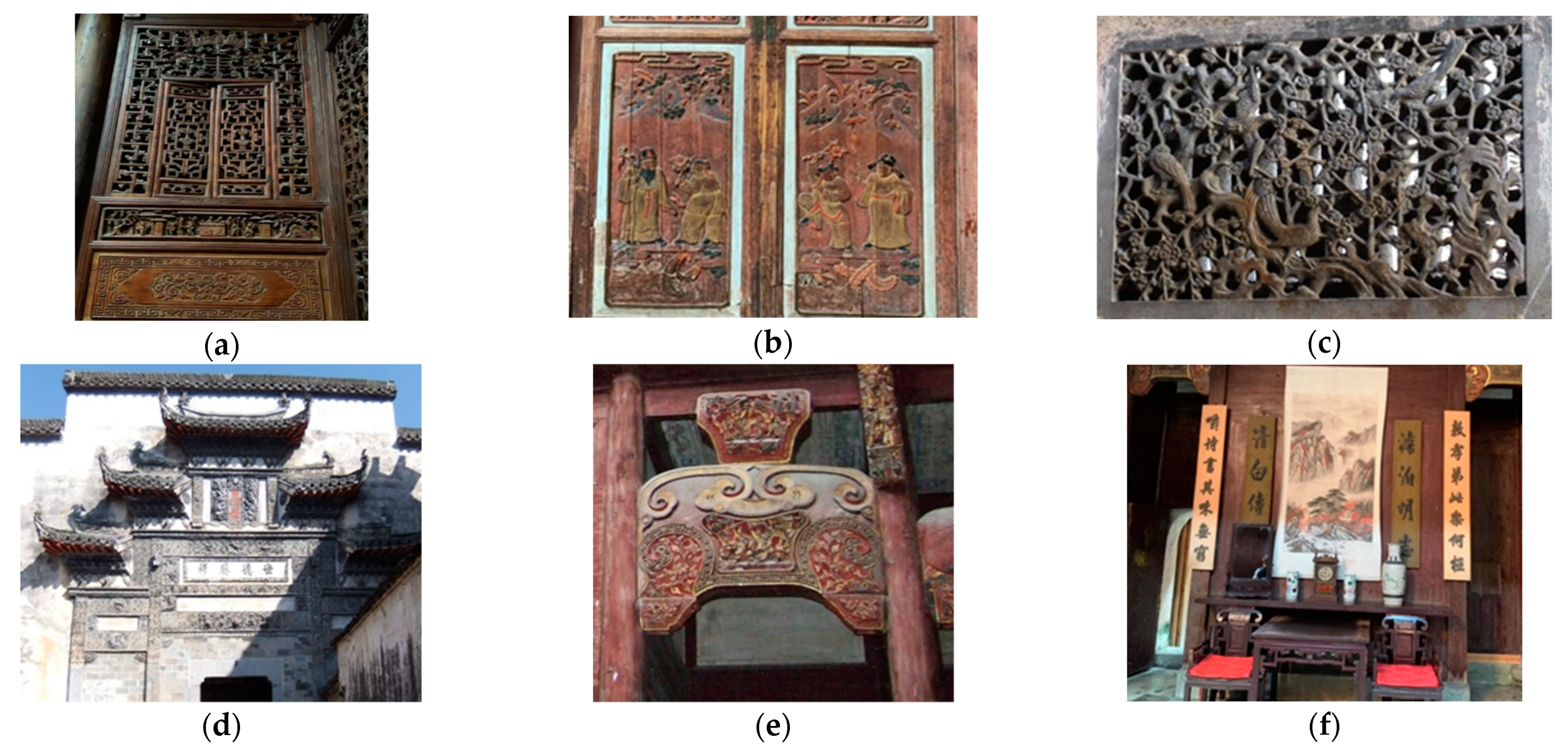

4.2. Characteristics of Traditional Vernacular Houses in Hongcun

4.3. Cultural Roots of Traditional Vernacular Houses

5. Residents’ Practices Regarding the Sustainable Development of the Residential Landscape

5.1. Material Level: Reconstructions of Spatiality by Residents

5.2. The Non-Material Level: The Reconstruction of Culture by Residents under Tourism

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Timothy, D.J.; Nyaupane, G.P. (Eds.) Cultural Heritage and Tourism in the Developing World; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Langston, C.; Wong, F.; Hui, E.; Shen, L.Y. Strategic assessment of building adaptive reuse opportunities in Hong Kong. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 1709–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. The Historic Urban Landscape paradigm and cities as cultural landscapes. Challenging orthodoxy in urban conservation. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, S. Reassembling nuremberg, reassembling heritage. J. Cult. Econ. 2009, 2, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrami, E.; Mason, R. Values and Heritage Conservation: Research Report; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bohua, L.; Peilin, L.; Yindi, D. Research progress on transformation development of traditional villages’ human settlement in China. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 1886–1900. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jing, F.; Jzab, C.; Ydab, C. Heritage values of traditional vernacular residences in traditional villages in Western Hunan, China: Spatial patterns and influencing factors. Build. Environ. 2020, 188, 107473. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.C. The predicament and way out of traditional villages. Folk Cult. Forum 2013, 1, 7–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Customized authenticity begins at home. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevoets, B.; Van Cleempoel, K. Adaptive Reuse as a Strategy towards Conservation of Cultural Heritage: A Survey of 19th and 20th Century Theories. In Proceedings of the IE International Conference Reinventing Architecture and Interiors: The Past, the Present and the Future, London, UK, 29–30 March 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Su, B. Rural Tourism in China. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1438–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1973; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Orbasli, A. Tourists in Historic Towns: Urban Conservation and Heritage Management; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, T.C. Cultural heritage tourism engineering at Penang: Complete the puzzle of the ‘The Pearl of Orient’. Syst. Eng. Procedia 2011, 1, 358–364. [Google Scholar]

- Richon, M. UNESCO-Rural Vernacular Architecture: An Underrated and Vulnerable Heritage. Futuropa 2008, 1, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Greenop, K. From ‘neo-vernacular’ to ‘semi-vernacular’: A case study of vernacular architecture representation and adaptation in rural Chinese village revitalization. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 1128–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunt, A. Cultural geography: Cultural geographies of home. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2005, 29, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastergiadis, N. Dialogues in the Diasporas: Essays and Conversations on Cultural Identity; Rivers Oram Press: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Myga-Pitek, U.; Jankowski, G. Tourism impact on the natural environment and cultural landscape. Analysis of chosen examples of highlands. Probl. Landsc. Ecol. 2009, T. XXV, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R.; Ollenburg, C.; Zhong, L. Cultural landscape in Mongolian tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, M.; Markham, F. Tourism, capital and the commodification of place. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 44, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alumäe, H.; Printsmann, A.; Palang, H. Cultural and Historical Values in Landscape Planning: Locals’ Perception; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- ALMohannadi, A.; Furlan, R.; Major, M.D. A Cultural Heritage Framework for Preserving Qatari Vernacular Domestic Architecture. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, D.C.; Soper, A.K.; Metro-Roland, M. Commentary: Gazing, performing and reading: A landscape approach to understanding meaning in tourism theory. Tour. Geogr. 2007, 9, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkenli, T.S. Landscapes of tourism: Towards a global cultural economy of space? Tour. Geogr. 2002, 4, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The Concept of a Tourism Area Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management of Resources. Can. Geogr. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.A.; Gl, B.; Ming, X.C. The linguistic landscape in rural destinations: A case study of Hongcun Village in China. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104005. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X. Commodification and the selling of ethnic music to tourists. Geoforum 2011, 42, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inskeep, E. Tourism Planning an Integrated and Sustainable Development Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991; pp. 342–345. [Google Scholar]

- Kreisel, W.; Reeh, T. Tourism and landscape in South Tyrol. Cent. Eur. J. Geosci. 2011, 3, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, B. The Spatial Factors of Cultural Identity: A Case Study of the Courtyards in a Historical Residential Area in Beijing. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bao, J.G.; Su, X.B. Studies on tourism commodificationin historic towns. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2004, 59, 427–436. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Wan, X.; Fan, X. Rethinking authenticity in the implementation of China’s heritage conservation: The case of Hongcun Village. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. “It is my home. I will die here”: Tourism development and the politics of place in Lijiang, China. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2012, 94, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, P.; Jones, O. Dwelling, place, and landscape: An orchard in Somerset. Environ. Plan. A 2001, 33, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesuriya, G. Living heritage. In Sharing Conservation Decisions; Alison, H., Jennifer, C., Eds.; The International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property: Rome, Italy, 2018; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Poulios, I. Discussing strategy in heritage conservation living heritage approach as an example of strategic innovation. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 4, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, I. Moving beyond a values-based approach to heritage conservation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Ical Sites 2010, 12, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.L. Impacts of urban renewal on the place identity of local residents—A case study of Sunwenxilu Traditional Commercial Street in Zhongshan city, Guangdong province, China. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 12, 311–326. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, C.O. The Morphology of Landscape. Univ. Calif. Publ. Geogr. 1925, 2, 19–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape; Croom Helm: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D. Landscape and surplus value: The making of the ordinary in Brentwood, California. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1994, 12, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G. Feminism and Geography: The Limits of Geographical Knowledge; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson, H. The intercorporeal emergence of landscape: Negotiating sight, blindness, and ideas of landscape in the British countryside. Environ. Plan. A 2009, 41, 1042–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorimer, H. Cultural geography: The busyness of being “more-than-representational”. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2005, 29, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatmore, S. Materialist returns: Practising cultural geography in and for a more-than-human world. Cult. Geogr. 2006, 13, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, M. In Comes I: Performance, Memory and Landscape; University of Exeter Press: Exeter, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson, H. Non-representational approaches to body landscape relations. Geogr. Compass 2010, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Survival of Capitalism: Reproduction of the Relations of Production. J. Clin. Hypertens. 1976, 16, 346–347. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. Toward a political economy of tourism. In A Companion to Tourism; Lew, A.A., Hall, C.M., Williams, A., Eds.; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Devine, J.A. Colonizing space and commodifying place: Tourism’s violent geographies. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The Logic of Practice; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Pascalian Meditations; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.L.; Zhang, Y.; Claudia, S. Protection and regeneration of traditional buildings based on BIM: A case study of Qing Dynasty tea house in Guifeng village. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 4, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.G.; Li, T.S. The Italian experience of conservation and rehabilitation for the vernacular dwellings of traditional villages: A case study of regione Piemonte. Urban Plan. Int. 2016, 31, 110–115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.H. Hongcun Village; Jiangsu Education Publishing House: Nanjing, China, 2005. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yao, J.; Zhao, S.Y. World Cultural Heritage Hongcun: Analysis of the structural factors of the development of Hongcun’s spatial form. Southeast Cult. 2005, 5, 48–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.H. Hongcun: World Cultural Heritage Road; Oriental Press: Beijing, China, 2021. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.; Jie, H. Urban Space4: Spatial Analysis of Traditional Village of Hongcun World Culture Heritage; Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 2009. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.Q. Waterways in Hongcun; Jiangsu Fine Arts Press: Nanjing, China, 2007. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Cheng, S. Traditional Construction Technique of Hui-style Dwellings; Anhui Science and Technology Publishing: Hefei, China, 2013. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qin, H. The System of the Palace and the Rule of the Palace: A Probe into the Institutionalization of Traditional Chinese Architectural Ethics. Stud. Ethics 2014, 5, 27–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T. Ming History; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1974; Volume 68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X. Research on the social significance and ethical order concept of Huizhou traditional residential space: Taking Chengzhitang in Hongcun Village of Yixian County as an example. Jianghuai Forum 2010, 2, 150–152. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. Dwellings in Yixian County; China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shan, Q. Series of Chinese Residential Architecture: Anhui Dwellings; China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X. Huizhou Culture; Liaoning Education Press: Shenyang, China, 1995. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wijesuriya, G. The past is in the present. In Conservation of Living Religious Heritage; Stovel, H., Stanley-Price, N., Killick, R., Eds.; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2005; pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, S.M.; Jones, S. Concrete and non-concrete: Exploring the contemporary authenticity of historic replicas through an ethnographic study of the St John’s of the St John’s cross replica, Iona. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 1169–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecco, M. Genius loci as a meta-concept. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 41, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zuo, D.; Li, C.; Lin, M.; Chen, P.; Kong, X. Tourism, Residents Agent Practice and Traditional Residential Landscapes at a Cultural Heritage Site: The Case Study of Hongcun Village, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084423

Zuo D, Li C, Lin M, Chen P, Kong X. Tourism, Residents Agent Practice and Traditional Residential Landscapes at a Cultural Heritage Site: The Case Study of Hongcun Village, China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084423

Chicago/Turabian StyleZuo, Di, Changrong Li, Mingliang Lin, Pinyu Chen, and Xiang Kong. 2022. "Tourism, Residents Agent Practice and Traditional Residential Landscapes at a Cultural Heritage Site: The Case Study of Hongcun Village, China" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084423

APA StyleZuo, D., Li, C., Lin, M., Chen, P., & Kong, X. (2022). Tourism, Residents Agent Practice and Traditional Residential Landscapes at a Cultural Heritage Site: The Case Study of Hongcun Village, China. Sustainability, 14(8), 4423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084423