1. Introduction

Co-operatives are increasingly being recognized as important contributors to inclusive, sustainable and fair development. However, the co-operative movement faces a multitude of challenges, including the lack of access to credit. The Italian co-operative sector features an important financing tool: the solidarity funds (Fondi Mutualistici in Italian). In 1992, Law 59 established those financial institutions that are owned by the co-operative associations. By law, all co-operatives have to transfer to the mutual funds (or to the Government if they do not belong to any co-operative association) 3% of their profits. In the past 25 years, the solidarity funds have been allocating large resources, creating a financial virtuous cycle that could be inspiring for other nations. The solidarity funds promote innovative and inclusive co-operative practices as well as training and university education. Examples of similar initiatives can be found in other countries, mostly where the co-operation culture is more established. In this paper, we look at Canada, France and the United Kingdom to further explore the nature and relevance of mutualistic finance.

Co-operative behaviors are spontaneous in human beings [

1,

2]. Informal co-operation was also rather spontaneous, even frequent, in many primitive, ancient and early modern societies [

3,

4,

5]. At the village or town level, the maintenance of waterways, the erection of public infrastructures and the harvests were often managed collectively on the basis of a principle of reciprocity and solidarity. In this paper, we refer to the modern co-operative movement and to the management of co-operative firms.

Since Rochdale, the idea of running firms as a collective of workers or consumers spread across the globe, including tiny island nations in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. However, national and local co-operative movements rarely appeared spontaneously; the co-operative business model travelled across borders thanks to intellectuals, missionaries, politicians, philanthropists or books. The British Empire contributed to this diffusion among its dominions [

6,

7].

By the beginning of 1900, virtually in every nation, the first co-operative and co-operative associations had been established. This was the case in the early experiences thanks to utopian Socialists such as Owen, Fourier, Proudhon or Saint-Simon [

8]. Later, Communist, Socialist, Liberal and Christian Democrat politicians or community leaders contributed to empowering workers and consumers by suggesting that they organise around a co-operative business. Similarly, it was thanks to Christian priests that the co-operative idea was disseminated. At times, when politics or religion were not involved, it was the owner of the firm itself who would recommend workers adopt a form of collective ownership; this was the case with John Lewis and many Italian firms that were donated to the workers on the condition that they would organise them in the form of a co-operative [

9,

10].

We argue that although co-operatives are spread virtually all over the world, they were not the result of a spontaneous emergence. On the contrary, co-operative firms spread and developed with the support of radical initiatives and an adequate institutional environment. Co-operatives have been flourishing the most in areas where they were supported by a so-called ‘enabling environment’, involving appropriate legislation, co-operative associations, targeted funding opportunities from members, co-operative banks and local, national and supranational institutions [

10].

A key specificity, and issue, is that the property rights system of a co-operative firm makes them difficult customers for traditional financial institutions. We refer to the voting system, to the constraints on the remuneration of capital, to the limits to trading shares and the liquidation of capital [

11], hence the need for a specialised actor, the solidarity funds, willing to join with both loans and equity. For instance, the EBTDA normally appears weaker than traditional companies because, in the case of co-operatives, the remuneration of members (called ‘ristorno’ in Italy) has been already deducted. Another typical financial issue is that the per capita voting system discourages the attraction of additional equity investments. Moreover, despite striving for competitiveness, co-operatives also maintain a focus on safeguarding employment levels and achieving social and environmental objectives.

In this paper, we focus on Italy and, specifically, on one institutional ingredient: the presence of solidarity funds. They are a mutualistic financial institution devoted to the support of the co-operative movement. They are funded by voluntary or compulsory contributions from co-operative firms. Despite the recognised role at the Italian national level of solidarity funds in supporting the development and flourishment of the co-operative movement, the research on this specific topic is still limited. Nevertheless, the main indicator of how successful this policy has been the survival and growth of the solidarity funds themselves. They are financial institutions subject to standard control and supervision by the regulators. In the past 30 years, their capitalisation and participation portfolio have proved the financial and business sustainability of their mission. In addition, moving to actual environmental and social sustainability, the Italian solidarity funds do also assess the funding applications based on corporate social responsibility metrics as described in their annual social reports of the solidarity funds.

There are national varieties and differences, but mutual solidarity funds usually operate with financial tools (loans, mortgages, equity participations) to support start-up or established co-operatives [

12]. In some cases, they also support the co-operative movement more broadly by funding trainings, university programmes and research. While the solidarity funds were established to accumulate resources and to be used especially in periods of growth, their role is becoming increasingly important during crises such as the 2007 financial crisis and the more recent recession triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Therefore, the study seeks to highlight the role of solidarity funds in the development and support of national co-operative movements by adopting a case study approach based on the analysis of four different experiences (Italy, France, the United Kingdom and Québec as a specific Canadian province with a French institutional environment). The analysis provided an opportunity to demonstrate that—despite the limited available research on this related subject—solidarity funds emerged globally with similar objectives. Since their establishment in 1992, these mutual finance funds have been putting in practice the principle of external mutuality, and they have supported the start-up and growth of co-operatives in every sector and every region. This tool could be easily replicated elsewhere in the world, regardless the stage of development of the co-operative movement there.

The mechanism facilitates the capitalisation of firms that otherwise might have difficulties and guarantees that resources are not wasted once a co-operative ceases to exist. The Italian policymaker was particularly brave to establish such a regulation in 1992. That was the time when in many Western countries, the co-operative model appeared obsoleted and doomed to extinction. In that decade in the UK, for instance, we observed a process of demutualisation that led old building societies and co-operative unions to transform themselves into standard financial institutions [

7,

13]. The co-operative financial institutions in Great Britain were considered obsolete then. Instead, their transformation into standard banks contributed to the financial crisis of 2007. For instance, the tragically famous Northern Rock was originally a building society; it demutualized in 1997 and became Northern Rock bank. It had to be nationalized in 2008 and was later sold to Virgin Money.

In order to identify the key role of solidarity funds in supporting the development of the co-operative movement, the study will start with

Section 2, where we present the Italian case. In

Section 3, we briefly mention relevant international experiences. In

Section 4, we offer policy recommendations.

2. The Italian Solidarity Funds: An Experience of Promotion and Development of the Co-Operative Movement

The solidarity funds (Fondi mutualistici in Italian) were introduced in Italy on 31 January 1992, by Law 59. They were born as institutions for the promotion and the development of the co-operative movement; on the one hand, they were conceived to consolidate the co-operative sector in opposition to the escalating wave of privatisations of those years, with the purpose of making the funds vehicles of financing exclusively for the co-operative system. On the other hand, the objective was also to provide the national co-operative associations with appropriate mechanisms to carry out their role [

14].

With the establishment of the solidarity funds, the legislator attempted to economically empower the co-operative sector to make up for its structural financial deficit through a specific backing mechanism; furthermore, this innovation contributed to rendering the co-operative associations more independent from political parties. As [

14] explains, in virtue of Law 59/1992, co-operative enterprises are authorised ex lege to turn to a particular self-financing procedure, hence maintaining the public resources directed to the co-operative sector within its boundaries. Likewise, another important aspect is related to the premises of corporate growth that the regulatory measures aim to strengthen, levelling the competitive disparities [

15] between traditional capitalistic companies and co-operative firms.

The theoretical reasons behind the funding difficulties for co-operatives were analysed by [

11]. They developed an analytical economic model of financing and growth in co-operatives. They include in their analysis the element of access in co-operatives and free riding. This can explain why co-operatives might end being undercapitalised or reluctant to fund innovation. Additionally, ref. [

16] have studied the credit constrains that are specific to co-operatives. Additionally, ref. [

17] have identified the effects of uncertainty and capital source on the co-operative firm leverage. Ref. [

18] explain that credit unions perform a different function in rural communities than commercial banks, hence confirming the need for financial institutions specialised in non-mainstream operations.

Through this innovation, the Italian legislator established in the legal system the so-called external mutuality [

19]. The idea of external mutuality, with respect to internal mutuality, stands for pursuing the general interest of the community towards human promotion and social integration of citizens. On closer inspection, this novelty brings along the idea of a sacrifice, a transfer of resources from individual co-operatives to the entire sector for a higher good; it clearly represents a characteristic element that we cannot find in the capitalistic counterparts [

20], which tend to have easier access to standard capital markets.

There are many reasons why co-operatives can be considered different from standard capitalist companies [

21,

22]. One of these is so-called external mutuality. Co-operation among co-operatives does not necessarily mean an exchange of resources from one co-op to another, but rather the external mutuality can generate business growth and contribute to co-ops’ development in the community, sustaining the movement while creating a solid market environment for co-operatives [

23].

The Italian fondi mutualistici find their roots in the ideology of external mutuality, the systemic solidarity between co-operatives, combined with the social purpose that the Italian Constitution attributes to them, tied with the intergenerational nature of the co-operative reserve capital specifically and more broadly of the entire co-operative movement (Genco et al., 2014). Hence, external mutuality is reflected in the mutuality towards future generations, and the solidarity funds act as recipient and guarantors of these resources.

Solidarity funds are instituted by the Annual General Meeting of the co-operative associations; on that occasion, the fund’s endowment is deliberated, simultaneously to the definition of the terms of its separation from the association’s assets. In Italy, the admitted corporate structure is that of a joint-stock company, with some peculiar features claimed by law, such as the non-profit nature of the organisation, the mandatory subscription of 80% of the equity by the related co-operative association, auditing activity conducted by the Ministry of Labor and commitment to reinvesting corporate profits.

In Italy, there are five active solidarity funds: Coopfond, Fondosviluppo, General Fond (the three funds of Alleanza delle Cooperative Italiane, ACI (The Alleanza delle Cooperative Italiane is the national apex organisation coordinating the three main co-operative associations in Italy (AGCI, Confcooperative Nazionale and Legacoop Nazionale). Overall, there are about 39,000 co-operatives associated representing 90 percent of the whole Italian co-operative movement in terms of employment (1,150,000 workers), turnover (EUR 150 billion) and membership (more than 12 million people, one out of five Italians))), Promocoop and Promocoop Trentina. Between 1992 and 1993, these financial institutions were established, respectively, by Legacoop Nazionale, Confcooperative Nazionale, Associazione Generale Cooperative Italiane (AGCI), Unione Nazionale Cooperative Italiane (UNCI) and, lastly, the Trentino Cooperative Federation. Even if Law 59/1992 established earmarking for the activities of the solidarity funds, each entity allocates resources based on the different types of membership of the co-operative movement. For instance, Coopfond, Fondosviluppo and General Fond are the expressions of different socio-cultural and political backgrounds, coming, respectively, from the socialist–communist, catholic and liberal co-operative organisations. Nonetheless, the ideological divergences have diminished over the years, and the establishment of the alliance in 2011 contributed to increasing the synergies and joint efforts of the three associations.

Coopfond is the company that manages the solidarity fund associated with

Legacoop Nazionale, holder of the entire EUR 120,000 share capital [

24].

Fondosviluppo is the solidarity fund of the Italian Cooperative Confederation (

Confcooperative), a joint-stock company with EUR 120,000 share capital, whose shares are divided between Confcooperative, which holds 80%, and Federcasse, the Italian federation of co-operative credit and rural banks, which holds the remaining 20%, (for the Fondosviluppo website, see ref. [

25]).

General Fond is the joint-stock company that runs the solidarity fund of AGCI, and 97.5% of it is owned by the related co-operative association and 2.5% by Assoforr (Source: Museo virtuale della cooperazione:

https://www.cooperazione.net/museo-virtuale accessed on 10 January 2022 [

25]), the National Consortium for Training and Research, which serves as an educational agency (for the Museo virtuale della cooperazione website, see ref. [

26]).

The funds’ exclusive mission is to contribute to the start-up of new co-operatives and to support those already existing, creating the conditions for the development of the co-operative movement, promoting initiatives to enhance co-operation—particularly the programmes focused on technological innovation, employment growth and the progress of the most disadvantaged areas and of Southern Italy.

2.1. Solidarity Funds’ Sources of Financing

The funds’ financial resources have several sources and different natures; allocated assets can be both private and public, and the resources can be either imposed or received as donations [

27]. In the following paragraphs, we consider the typical and general functioning of the financial management of Italian solidarity funds. However, there are also some singularities, as it is for Fondosviluppo, which has developed an ad hoc system by virtue of the collaboration with the network of co-operative credit banks, thus not entirely following the same scheme.

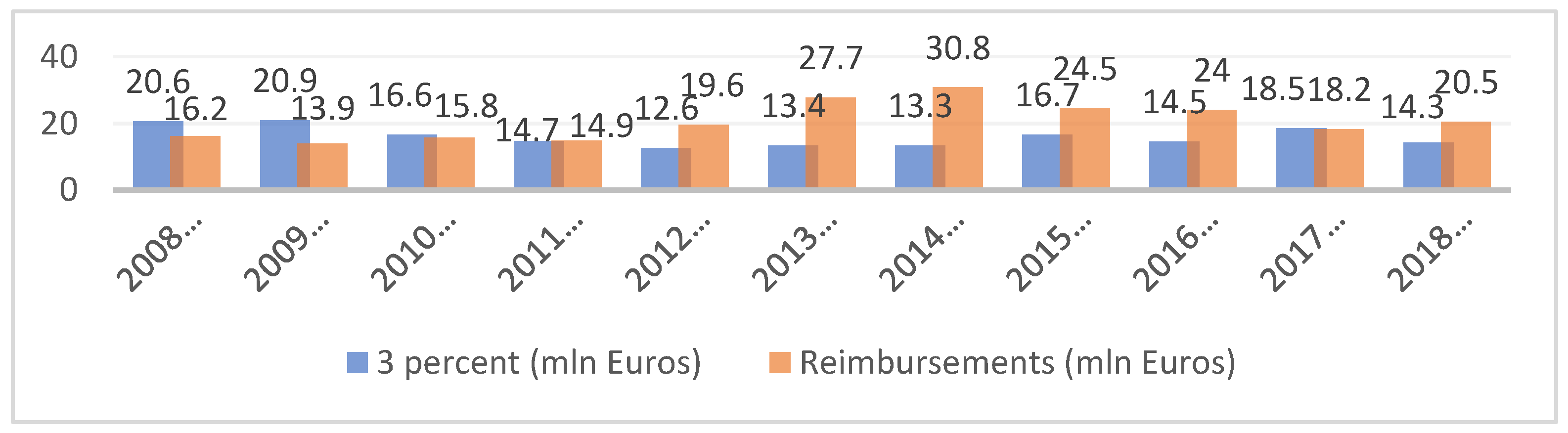

The capitalisation of the solidarity funds is supported by multiple sources. The largest one is the mandatory transfer of 3% of annual profits from member co-operatives and consortia. This is prescribed by article 11, paragraph 4, of Law 59/1992. In 2018, the three solidarity funds associated with the

Alleanza delle Cooperative Italiane (ACI) received EUR 40 million thanks to this provision. Additionally, the solidarity funds receive the remaining capital from member co-operatives that went into liquidation, in accordance with article 11, paragraph 5, of Law 59/1992. There are also capital inflows thanks to donations or contributions, i.e., public financing for specific projects [

14]. In addition, the solidarity funds also earn profits from their own financial and capital investments.

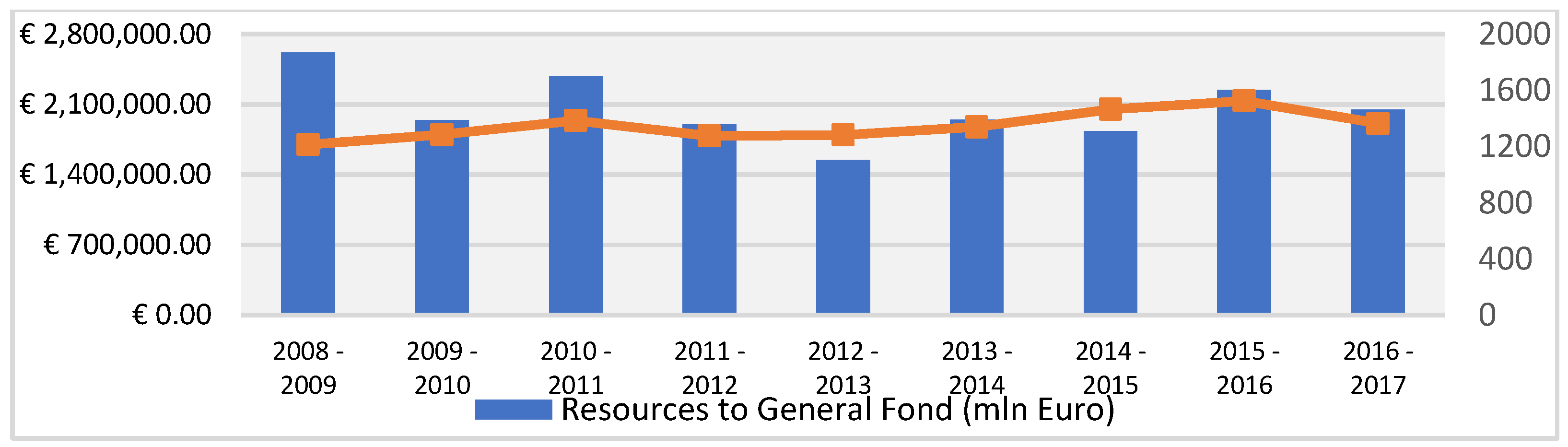

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show that Fondosviluppo is the largest actor in terms of both resources allocated and number of co-operatives reached. As far as repayments are concerned, thanks to the activities carried out by

Coopfond during the crisis—together with the reliability of the co-operative movement—repayment rates continued to be high, surpassing EUR 48 million in the last two years.

Overall, nearly EUR 205.6 million were repaid to Coopfond during the last ten financial years both through stakes in co-operatives or consortiums and reimbursing their loans, meaning that revolving procedures are a key aspect of maintaining and guaranteeing the sustainability of the solidarity fund, as shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 2 reveals that, regarding

Fondosviluppo, the sizable disparity between the two indicators is instead due to the specialisation of the fund, whose activity can be considered similar to that of a merchant bank rather than a typical bank. Indeed, during the last 10 years, a relevant amount of the ‘lending activity’ was operated by credit co-operative banks (BCCs) through a specific agreement that allowed around EUR 450 million of loans for 150 co-operatives, notably for investments in medium and big co-operative enterprises (source: Fondosviluppo).

Figure 3 reveals that GeneralFond, on average, must be contributing with much smaller transfers compared to the other two solidarity funds. Conversely,

Figure 1 and

Figure 3, respectively, reveal that for

Coopfond and

GeneralFond, there is a strong positive correlation between the resources received by the relevant co-operatives and the numbers of these co-operatives.

2.2. Areas of Intervention

The financing activity conducted by ACI’s solidarity funds aims at the promotion, at the development, at the entrepreneurial consolidation or at sustaining the integration of and between co-operatives. Measures might be carried out independently or in collaboration with other actors and in such a way as to ensure sharing risks; solidarity funds often offer a mutual guarantee to build co-operatives’ fixed assets [

29]. They operate following different paths and instruments. The main strategies adopted, specifically with regard to the actions of Coopfond, are:

- (1)

Revolving measures: the fund can grant financing, ensuring time frames and modalities or, differently, it can acquire a temporary shareholding in the capital of co-operatives, to sustain firms;

- (2)

Equity: funds can also acquire stable participations in companies where the ownership is held by co-operatives with the aim of pursuing the overall strategic objectives set for the co-operative movement;

- (3)

Active promotion: the solidarity fund can offer non-repayable grants, with a fixed maximum amount per year (i.e., EUR 2 million with Coopfond), to initiatives of high social relevance to promote co-operative values and principles [

30].

2.2.1. Revolving Measures

Revolving resources are addressed specifically (but not exclusively) to small and medium co-operative enterprises, which often face problems in accessing the market of capitals. Usually, these loans benefit from subsidised rates, and by the time firms pay them back, the fund allocates the returns in other credits, thus regenerating itself.

In this field, interventions focus mainly on four pillars: the creation of new co-operatives, development plans, corporate consolidation and restructuring and, lastly, merging processes. In order to obtain financing from the funds, co-operatives have to elaborate and present a solid business plan.

Restructuring measures are put in place preferably with workers’ co-operatives as well as with co-operatives that do not have a completed plan yet, so as to allow a punctual analysis of the entrepreneurial/industrial quality of the project and the possible intervention modalities of each fund. In the project assessment phase, particular attention is paid to the role played by the members in conferring new capital to the co-operative [

30].

Fondosviluppo operates in a unique way in this area of action; indeed, the fund has special agreements with co-operative credit banks (BCCs) that are associated with Confcooperative. Ordinary loans are always granted by the BCCs, while the procedures for nominal capital are carried out by Fondosviluppo itself (for Fondosviluppo website, see ref. [

31]).

Overall, from 2008, Coopfond has financed revolving measures worth about EUR 263.3 million. Again, as recalled above, the effects of the economic crisis are notable due to the drastic decline in financing, especially after the financial year of 2010/2011 when Coopfond approved projects for EUR 24.2 million (about 40 percent less compared to 2009/2010). Most importantly, taking into consideration only the resources used to finance this first area of action and comparing numbers with those concerning the 3 percent, an interesting first comment arises: Coopfond, at least in these last financial years, has confirmed its redistributive role as laid out by Law 59/1992, keeping a high investment rate throughout the period.

In the last six financial years, Coopfond has supported 233 revolving activities for a total of EUR 163.6 million

Figure 4. These are remarkable figures knowing that, in 2015, the operability of the solidarity fund was severely resized due to the effects originated from ministerial Decree 53/2015 on financial intermediaries. The Decree stopped the solidarity fund from financing new programmes by granting loans to co-operatives and consortiums, limiting the activities only to investments through risk capital [

32]. Nevertheless, in 2017, the Ministry of Economy and Finance issued a new decree allowing the solidarity funds to start again, granting credit to the co-operative movement.

General Fond, for its part, invests in the co-operative system a share of ¼ of resources inflow, which corresponds approximately to EUR 550,000.

2.2.2. Equity

The solidarity funds can acquire stable equity participations in co-operatives aiming to pursue the strategic objectives or to promote instrumental activities in order to follow finalities and priorities in accordance with Law 59/1992 and their mission.

In particular, the funds tend to intervene preferably in initiatives that could be promoted in collaboration with other partners, external or internal to the co-operative movement, and between funds as well. Most importantly, they co-operate to find such actors in order to increase the operational capacity and the financial effectiveness of investments supported [

30].

Regarding specifically the activity of Coopfond, it receives and examines requests coming from subjects asking to be financed. When the project is financially viable and Coopfond considers it positively, the maximum amount that the fund can grant is set to three million euros, unless otherwise specified by the board. Furthermore, the participation cannot be higher than paid-up capital by members of the co-operative or the consortium [

33] (Coopfond, 2020).

There are mainly two kinds of permanent participations depending on the actor involved: a financial partner or an industrial one. While the first has signed a higher number of agreements with Coopfond, the latter has received more than double the amount of money from the solidarity fund. However, the analysis should consider the fact that, in 2015, Coopfond acquired stakes in one single actor (Cooperare s.p.a.) for EUR 17.7 million, resulting in a drastic increase in figures [

30].

Comparing the total amount of investments promoted in this second area with revolving interventions, the latter receives nearly double the funding (EUR 146.9 against 73.5 million in participations), confirming the difference in terms of ordinary and special nature of the two interventions.

2.2.3. Inclusive and Responsible Investments through the ‘Active Promotion’

The board of each fund can decide, each financial year, to allocate additional resources (for a total amount of two million euros for Coopfond) in order to sustain several activities, most notably: measures for potential beneficiaries aimed at improving the financing request or the access conditions to the solidarity fund; measures to support co-operative entrepreneurship, especially in the Mezzogiorno (Namely the Italian regions of Abruzzo, Basilicata, Calabria, Campania, Molise, Puglia, Sicilia and Sardegna); projects presenting a high social purpose or strong co-operative solidarity towards the entire community; training, research and study programmes, which are of particular interest for the co-operative movement, in accordance with article 11, paragraph 3, Law 59/1992, to be realised by also granting scholarships [

30].

All these activities might be carried out through the provision also in the form of direct grants. In particular, ACI’s solidarity funds jointly promote different post-graduate courses and master’s programmes.

In the next section, we will identify similar schemes for the support of the co-operative sector in:

- -

Québec (Canada);

- -

France;

- -

the United Kingdom;

- -

Spain.

3. Implementing Solidarity Funds: Insights from Canada, France and the United Kingdom

In Italy, the co-operative sector is financially supported by mutual solidarity funds that finance several projects and initiatives, while providing backing activities and training. Moreover, since they are specifically dedicated to social economy enterprises and embrace their culture of co-operation, these funds represent an important alternative when standard financial institutions deny their support. Solidarity funds do instead ‘speak their same language’ and understand their logics [

34].

In his classification of reciprocity, ref. [

5] presents a matrix with four entries, as seen in

Table 1. The success of the co-operative sector is based predominantly on behaviours driven by mutuality: Internal (among members) and external mutuality (among co-operators of different, independent co-operatives). For the co-operatives belonging to the social and solidarity sector, behaviours based on altruism are equally crucial. The solidarity funds were established to support external mutuality and to facilitate the transmission of financial resources (among others) between more and less successful and developed co-operative firms.

We argue that the Italian case is characterised by favourable conditions for the start-up or the consolidation of co-operative firms. Before moving to conclusions and recommendations, other national cases are reviewed.

3.1. Québec

The Canadian co-operative sector can rely on different initiatives and programmes supporting the social economy, also thanks to cultural factors that have contributed to shaping the structure of the national economy.

The Canadian Co-operative Investment Fund (CCIF) was recently established, in 2017, by the association Co-operatives and Mutuals Canada to bridge the financial gap that hinders the co-operative economy. Joining up with other financial partners or providing grants autonomously by the current management of resources procured by its investors and borrowers, the main products stipulated by the fund are loans, equity investments in share capital and quasi-equity financing with a delayed return. With a capital of USD 25 million, the primary projects supported aim to reinforce existing co-operatives, parallel to the efforts implemented to follow traditional companies through the reorganisation towards co-operative structure.

In addition to the CCIF, from 2006, in Québec, enterprises which are active in the social economy can borrow money from the trust Fiducie du Chantier created by The Chantier de l’Economie Sociale, similar in its role to a federation, whose loans are part of the so-called patient capital: loans are granted without warranties and to be paid back in 15 years [

36]. The Quebecois social economy is composed of co-operatives, mutual-benefit societies and associations; the trust’s lending activity is carried out following two main objectives. On the one hand, enterprises can borrow up to USD 250,000 in order to face operational improvements, expansions and start-up development; on the other hand, the trust lending amount stretches to USD 1.5 million to acquire real estate properties [

37].

Data provided by the Réseau d’Investissement Social du Québec (RISQ), a network partner association of the trust, report how these investments have disentangled other forms of complementary financialisation (indeed, patient capital is accorded only if other sources of funding are available), with an estimated impact of USD 350 million and more than 3000 jobs created or preserved. The RISQ can allocate further resources by offering loans on nominal capital [

38]. Between 1997 and 2017, the trust allocated USD 28.2 million of resources, directed to 1085 loans [

39]. With an initial contribution of USD 30 million from the national government, which is represented on the board of the trust, and the ongoing consultation with trade unions, the trust represents a positive case of dialogue and collaboration of different actors towards the support of the social economy [

40].

In addition to the instruments offered by the Chantier de l’Economie Sociale, the Caisse d’Economie Solidaire Desjardins (CÉCOSOL) is one of the main financial instruments of Canadian SSE [

41]. The fund, which has its roots in trade union movements and mainly acts as a savings holder, contributes to supporting co-operative enterprises in partnership with other institutions, such as RISQ. Desjardins Capitals, a co-operative investor in patient capital, provides the Canadian economy with an additional fund, Essor et Coopération, exclusively dedicated to the financing of cooperative firms [

42].

One further instrument of co-operative support engaged in activities all over the world is the Co-operative Development Foundation of Canada (CDF), an international organisation formed in 1947 that partners with local entities in Africa, Asia and Latin America; the fund’s work, in the year 2017 alone, reached 213,000 women, men and children. The impacts pursued shall have results in terms of food security and nutrition, local economic development, climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies, inclusiveness of financial opportunities, capacity building and peace development. Clearly, all the projects promoted have as a common denominator the co-operative model as an instrument of human and socio-economic development, designed to set the basis for long-term sustainability and empowerment.

3.2. France

Similar instruments to the financial tools used by Italian solidarity funds are the solutions adopted by French co-operative movements to promote co-op enterprises. Socoden is a financial institution (structured as a co-operative) controlled by the General Confederation of SCOP (co-operative and participative firms owned by the workers), and it exists to support and promote SCOP and SCIC (co-operative firms of collective interest). Socoden intervenes by means of participation loans with a payback period from 3 to 7 years and a total amount of EUR 600,000; through equity shares (without voting rights); and by acting as guarantors for bank loans. As reported by the European Federation of Ethical and Alternative Banks and Financiers (FEBEA, 2020 (

https://www.febea.org/febea/members/socoden) accessed on 10 January 2022), Socoden manages activities amounting to EUR 15 million of participative loans, EUR 9 million in equity shares and loans guarantees for approximately EUR 50 million.

Scopinvest and Sofiscop are two other main financial instruments in the General Confederation’s hands, which operate with capital interventions, participatory shares and convertible obligations (Scopinvest) and guarantee mid-term loans [

43]. As reported by the General Confederation of Scop, Scopinvest was created to support equity formation next to corporate investment, improve financial structure supplying resources, finance firms’ internal and external growth and strengthen firms’ nominal capital in times of difficulty.

French co-operatives can also rely on other instruments belonging to the social and solidarity economy. The activity of IDES (Institut de Développement de l’Economie Sociale) lies in interventions oriented towards funding internal development and external growth of co-operative firms, associations and institutions of the SSE [

44]. Managed by ESFIN, IDES provides support in terms of equity, with an investment period between 7 and 12 years and for a maximum amount of EUR 1.5 million. Impact Co-opératif is an investment fund controlled by ESFIN, in partnership with Bpifrance, the co-operative credit and the co-operative movement, and its projects mainly finance long-term external growth and support workers’ buy-out, with investments extending up to EUR 7 million (ESFIN, see ref. [

45]).

Moreover, France’s additional contribution to the exemplification of alternative financial schemes in the social economy relates to pension funds. France, with an absolute supremacy of the public model, has been experiencing a gaining relevance of the so-called 90/10 Funds; between 90% and 95% of the fund is managed through traditional instruments, while a share ranging between 5% and 10% is dedicated by law to social economy entities (with exclusion of listed companies), which, despite the modest profitability, represent an important source of capitalisation for the economy.

The path to the creation of these funds started back in 2001, with the practical definition of which organisms could manage the mechanism and which could receive the investments; the final picture was adopted in 2014 by means of a specific law regarding social economy (Law No. 2014-856 of 31 July 2014 on the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE)), legislating also on the overall mechanisms of accreditation, check and control.

The 90/10 Funds were increasingly stimulated until 2010, when it became mandatory to include voluntary pension schemes for workers. From 2008 to 2015, the resources available to the 90/10 funds increased from EUR 898 million to EUR 6.067 million, with contributions received by approximately 900,000 workers, as reported by the consultancy firm Finansol. Available data also document how, in 2015, 6% of the resources received (a share of EUR 354 million) were addressed to social economy projects; in turn, 40% of this amount was allocated by financial institutions, and the remaining 60% was assigned through accredited institutions with a special role played by solidarity entities (i.e., co-operative banks).

The 90/10 Funds have been gaining increasing attention from the market, due also to the profitability in line with other products; for the year 2018, the total 90/10 Funds deposits amounted to EUR 9.3 billion, with a six-fold increase in 9 years [

46].

3.3. United Kingdom

The English Coop Loan Fund has been providing accessible finance to the co-operative economy since 1973. It is structured as a company limited by a guarantee and managed by the Co-operative & Community Finance, an independent organisation entitled to conduct investment business.

Funding is voluntarily donated by Cooperatives UK, the largest British co-op network, by Co-op Midcounties, East of England Co-operative Society and Chelmsford Star Co-operative Society. The scopes of the fund are to promote the creation of new co-operatives, or to expand the already existent ones, as well as to aid workers’ buy-out procedures and to help with property and capital equipment purchases. The loans granted by the fund can reach a maximum amount of GBP 85,000, are assigned unsecured, with no personal guarantees and are flexible with regard to lending terms (for Co-op Loan Fund’s website, see ref. [

47]).

One of the key elements of co-operative capitalisation in the United Kingdom is the community shares, redesigned and strengthened in 2009 by the federation Cooperatives UK and the central Government, together with local and community work associations. The functioning of the community shares is, in practice, similar to consumer co-operatives; however, they have integrated different kind of services and activities which are considered vital by the dwellers and inclusive in the socioeconomic framework of their neighbourhoods: a pub, a vegetable garden, a cultural centre, solar panels’ installation and many more [

48].

The mechanisms through which funds have been raised is somehow analogous to the public offer of exchange stocks, with the involvement of popular investors led by the interest in ameliorating the community. Since 2009, co-operative projects have been financed with GBP 150 million, raised by over 500 firms which received contributions of 150,000 investors in the UK [

49]; the owners of community shares are the owners of the co-operatives and associations constituted, managed through the co-operative principle of ‘one head, one vote’. Moreover, shares cannot be freely sold, unless if purchased by the entity itself and never at a higher price, in order to avoid enrichment from the operation; what is instead admitted is to pay back returns on the shares if the solvency is guaranteed and maintaining the interest rate at the minimum advisable rate to attract investors (two points below the standard bank interest, with a maximum of 5%).

The British case positively embodies the capability of redesigning traditional financial instruments into vehicles to support and enhance the values of the social economy. The Co-operative and Community Finance, since 1973, has financially supported co-operatives and social enterprises with loans up to GBP 150,000; no personal guarantee is required, and the only criteria demanded are employee or community ownership of the business and the democratic control over entrepreneurial exercise. Owning a capital of over GBP 4 million, the fund promotes projects whose area of action spans from renewable energy co-operatives to community-owned shops, pubs and facilities, but also invests in employee buyouts and workers’ co-operatives. Resources are acquired mostly by private investors, who seek to commit their capital to ethical sources of finance; indeed, one of the peculiarities of this fund is its potential ability to pay back dividends [

50].

3.4. Spain

For the purpose of our analysis, we have additionally taken into account the case of Spain regarding mutual funds. Notwithstanding, the Spanish experiences do not represent close similarities with the Italian case of solidarity funds for the co-operative enterprises.

In fact, the main organisations are active in social economy promotion, with the most attention focused on social enterprises supported by solidarity mutual funds; yet, those agencies are not specifically in support of the co-operative sector, even if within their activity relevant investments are dedicated to co-operative enterprises [

51]; they are more engaged in supporting social and solidarity associations and enterprises.

3.5. The Importance of Accessing Capital and Funds to Support the Role of Co-Operatives

The mutual funds have proven to be a stimulus for the co-operative and social economy in Italy and in other countries [

52]. Since their institution, they have actively supported thousands of co-operatives, as we have mentioned in the previous paragraphs, and strengthened various sectors with the primary goal being, as is also declared by the Italian constitution, art. 25, the social function of co-operation.

Co-operatives respond to modern challenges, with their engagement in social inclusion activities (such as offering job opportunities to migrants or through work integration co-ops for workers at risk), environmental conservation, climate change adaptation and mitigation projects (renewable energy co-operatives, organic farming), reinforcement of local communities (community co-operatives) and the green and circular economy [

53,

54]. Many of these positive experiences have faced obstacles in the access to capital, primary in the start-up stage, and the financial support of mutual funds and joint backup options turned business plans into reality. Indeed, in times of crisis, co-operatives have not only been shown to be resilient and solid economic agents [

55,

56,

57], but have also demonstrated their role in developing modern experiments, acting as social agents for economic, social and environmental purposes [

58]. Indeed, many of the co-operatives financed by the mutual funds have a common interest in adhering, both in the practice and in the objectives of their projects’ execution, to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the overarching framework of the Agenda 2030 [

59].

Since their establishment, solidarity funds have responded to the co-operative issue of ‘financialization’, supporting a new financial structure that appears distinct from the common financial architecture. Likewise, co-operatives, democratic ownership and governance, alongside their engagement in social and environmental goals while earning returns, highlight the differences among traditional private enterprises. Many of the financial instruments supplied by solidarity funds, as discussed in the previous paragraphs, are often similar to those of the conventional financial framework, while at the same time they prove elasticity of adaptation for social economy purposes, which typically require patient or long-term capital, or quasi-capital support [

60]. A further aspect to take into consideration is the positive features associated with a more diverse sector of financial services in terms of corporate ownership structure and business models, enhancing greater stability, higher responsibility, reduced systemic risk and better access to financial services [

61].

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we have described the origin and the role of the Italian solidarity funds [

62,

63,

64]. We have also offered an outlook on similar financial mechanisms in Québec, France, the UK and Spain. We argued that in the Italian case they proved to be very helpful.

In doing so, we have mentioned the financial constraints and specificities of the co-operative firm. The policymaker acknowledged this diversity.

The Italian case is the most developed by far. The other countries discussed have something in place, but internationally, solidarity funds are very rare and we support the idea of extending this tool as widely as possible.

With respect to the Italian solidarity funds, we have provided figures that describe the scale of their operations. We have also explained to an international audience the characteristics and the rationale of the Italian policy.

While the solidarity funds have worked very well in the past three decades and were proved to be very important particularly during the 2009 and 2020 crises, further research about their future role would be welcome.