3. Results

Statistically processed data are summarized in tables and graphs.

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 contain relevant information related to the factor analysis for closed-response items, and

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show the distribution of items by components in the varimax rotation axis system.

3.1. The Results of the Factor Analysis and the Internal Consistency for the Items of the Constructed Questionnaire

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test (KMO = 0.690) for the MS factor indicates a value >0.5, so it is above the Kaiser/Kaiser’s Criteria threshold, which verifies the adequacy of the sampling adequacy for analysis, according to

Table 1. The result of Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (χ

2 = 179.126 with Sig. = 0.000) indicates a good correlation between the MS factor items (rejects the hypothesis that the variables would not be correlated), so there are one or more common components to apply factor reduction via the PCA technique (principal component analysis). In this case, there are three main components, which cumulatively explain 57.20% of the total variance: Component 1 (34.165% of the variance), component 2 (12.806% of the variance), and component 3 (10.228% of the variance).

Table 2 indicates the loading of items/variables on the three main components after applying the orthogonal rotation procedure with the Varimax variant, which reduces/minimizes the number of variables with high loads (>0.6) for each component. Component 1 is strongly loaded on items MS11, MS10, MS12, and MS3 (quality of the relationship with the coach and teammates, support and motivation of the coach, and victory as a motivating factor) and secondarily (moderate) on MS1 and MS 6 (spectacularity of the game as motivation and involvement out of pure passion). Component 2 only has two items with strong loads: MS9 and MS5 (self-perception of rugby skills and financial motivation), but there are four items (MS10, MS1, MS6, MS2) with a moderate load (importance of victory, spectacularity of the game, involvement out of passion, motivation and family support). Component 3 also presents two items with a strong load: MS8 and MS4 (attractiveness of technical training and the existence of players as career models). It is observed that the item MS7 (existence of moments of abandonment) has weak loads for all components, but it will not be removed from the composition of the MS factor because the values presented above are also significant in its presence.

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test (KMO = 0.811) for the EB factor indicates a value of >0.5, being above the Kaiser/Kaiser’s Criteria threshold, an aspect that also verifies the sampling adequacy for analysis, according to

Table 3. The result of Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (χ

2 = 170.087 with Sig. = 0.000) also indicates a good correlation between EB factor items, so there are one or more common components, and factor reduction can be applied via the PCA (principal component analysis) technique. In this case, however, only two main components were found, which cumulatively explain 59.681% of the total variance: Component 1 (46.602% of the variance) and component 2 (13.079% of the variance).

Table 4 indicates the loading of the items/variables of the EB factor on the two main components after the application of the orthogonal rotation procedure with the Varimax variant. Component 1 is strongly loaded on items EB2, EB3, and EB1 (appearance of the feeling of physical superiority, satisfaction produced by training, effects on the formation of positive attitudes) and moderately on items EB4, EB8, EB6, and EB9 (positive effects on physical development, utility for an active lifestyle, frequency of injuries in rugby, utility of reintroduction in profile faculties) (

Figure 2). Component 2 has three items with a strong load: EB7, EB5, and EB9 (impairment of school performance, effects on health, usefulness of reintroduction in profile faculties). Furthermore, there are three items (EB3, EB4, and EB8) with moderate weight/load (satisfaction produced by training, positive effects on physical development, usefulness for an active lifestyle). It was observed that all items have strong (>0.6) or moderate (>0.4) loads for both or at least one of the components.

Table 5 shows the fidelity values (Cronbach’s Alpha) and those of Hotelling’s T-Squared Test.

The results related to the internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach’s Alpha) and the indicators of the equality test for the averages of the items corresponding to the two analyzed factors (Hotelling’s T-Squared Test) are summarized in

Table 5. For both factors (effects and benefits of motivational support), values of internal consistency >0.8 are obtained, an aspect that demonstrates the fidelity of the measurement of the questionnaire for the items with closed answers, thus confirming the first hypothesis of the research/H1. For Hotelling’s T-Squared Test, statistically significant values are recorded (

p < 0.001) for both factors, so we can conclude that there is diversity among the choice of answers/item scores, with the obtained averages not being equal, aspect: F1 (11,38) = 16.175; F2 (8,41) = 10.713, confirming, in this case, Hypotheses H1.2 and H1.3.

3.2. The Findings of the Analysis of the Results Obtained when Processing and Interpreting the Items with Close-Ended Answers (for the Two Factors) and the Items with Open-Ended Answers

Table 6 and

Table 7 show the values of Univariate tests, the comparison between the averages of the items for the U-15 and U-16 groups, the significance thresholds, and the values of Ƞ

2p, while

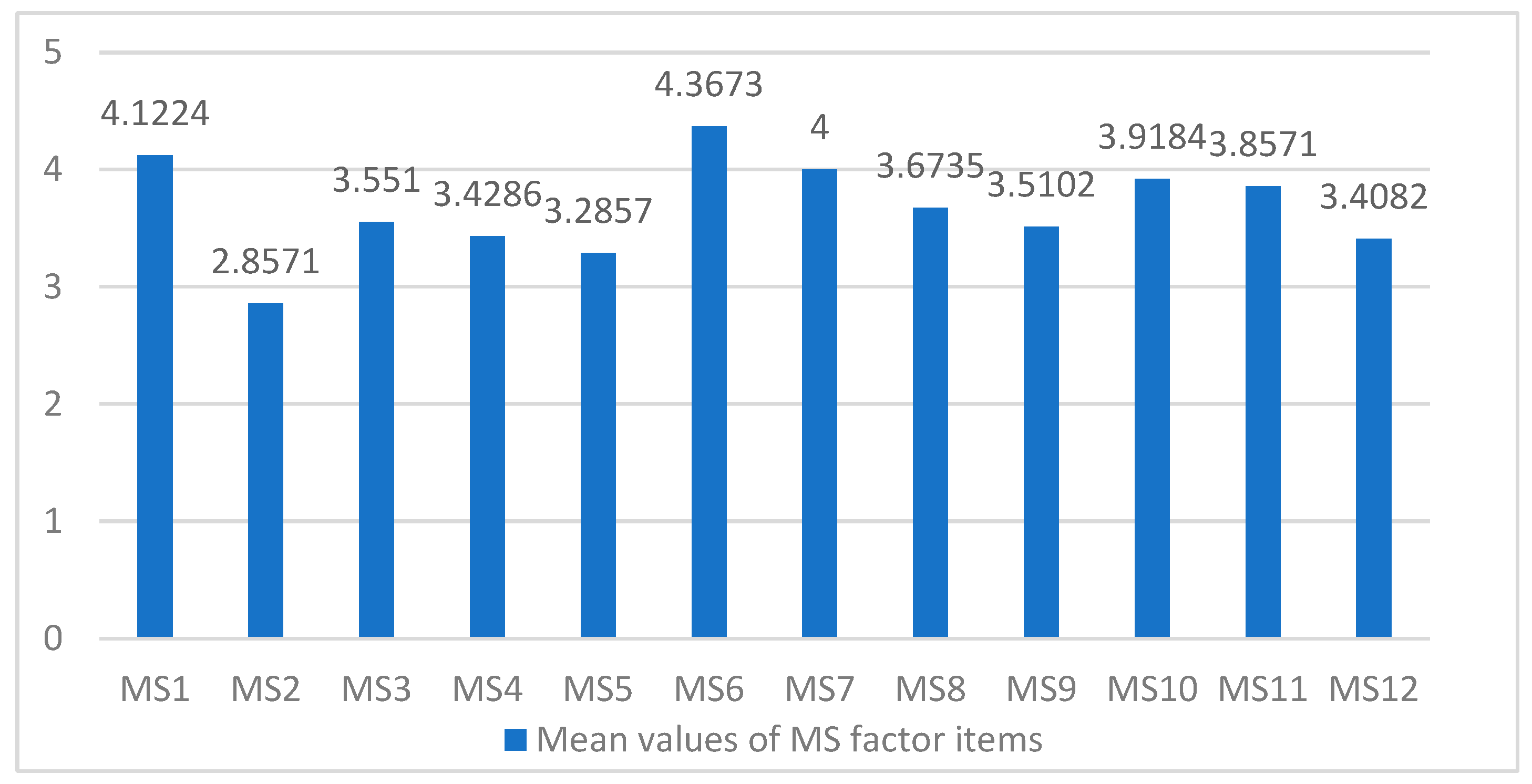

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show the average values of the items of the two factors for the whole group of athletes.

Table 6 summarizes the results of the variance analysis and the differences between the mean values of the U-15 and U-16 groups for the MS factor. Most of the values of F and the related significance thresholds indicate a lack of significance of the differences between the mean values (

p > 0.05), in addition to the weak values of Ƞ

2p. The only significant difference between the groups is in the case of item MS5 (financial motivation in rugby), where those in the U-16 group have a higher score than the U-15 group, with F = 7.629 and

p = 0.008. In fact, 14% of the variance in this item is explained by the age stage influence, so with the transition to a new group, money and financial security become more important, motivating factors. For the U-15 group, having role models to follow is more important, while the pleasure of involvement also has a higher average value. In this group, there are lower abandonment tendencies, and victory is also more important in motivation, compared to the U-16 group, which is a slightly surprising aspect if we take into account that the pressure of results is stronger with the selection in the higher age range. The U-15 group assigned higher scores to the relationships with the coach and teammates in influencing their own performance, so the relationship with authority and the quality of group interactions are perceived as more important. The U-16 team obtains higher average scores regarding the motivational support provided by parents/entourage and teachers and coaches, as well as the ability to self-perceive/self-evaluate their own skills needed in the game of rugby, thus being more confident in their own abilities to achieve high performance in sports.

Table 7 shows the results of the analysis of variance and the differences between the mean values of the U-15 and U-16 groups at the EB factor level. The only item where significant differences are reported in the opinions expressed by the investigated groups is EB8 (usefulness and accessibility of the game of rugby as an active lifestyle for any person), with the U-15 group being overly optimistic about this (F = 22.829,

p = 0.000), and 32.7% of the variance of this dependent variable being explained by the effect of age stages/independent variable. The major difference in opinions can be attributed to the greater experience of those in the U-16 team, who faced several problems associated with the game of rugby and better understand its difficulty and complexity, as well as the weaker popularity among all categories of the population. The enthusiasm of those in the U-15 group for most of the effects and benefits of rugby is noticeable, even if all the values of F and their thresholds are insignificant (

p > 0.05) and the values of Ƞ

2p are weak. The U-15 team has a high perception of physical superiority over other athletes (as a manifestation of the egotistic component and belonging to an exclusive group), has higher scores related to the effects of rugby on health and physical development, is more satisfied with the training and less affected by injuries (probably as a result of the shorter average duration of involvement and participation in training/competitions), and believes more in the usefulness of reintroducing the game of rugby in the profile faculties. The U-16 group obtains a higher average score related to the favorable effects on the attitudinal component, and this group also reports fewer problems related to the impact of school performances as a result of concentrating on a sports career, a sign that experience generates better adaptation to these multiple tasks (academic and sports). Insignificant differences between the mean values of the two groups (for most of the questions in

Table 6 and

Table 7) lead to the idea that. in these cases, Hypothesis H2.1 is not confirmed (

Figure 3).

Figure 3 shows the distribution of average scores for responses to MS factor items. It is observed that ranking highest in motivational support is the pleasure/passion for rugby, its spectacularity, the desire for victory/success, and the quality of the relationship with the coach (average scores > 4, related to the Likert scale), and ranked last is the quality of the relationship with teammates, financial motivation (with average values within the range of 3 and 4 on the Likert scale), and parental support in practicing this sport, with this last item having the lowest average value/<3, which is slightly surprising.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of average scores for responses to EB factor items. The highest values are related to the formation of positive attitudes, harmonious physical development, the usefulness of reintroducing the game of rugby in faculties, satisfaction induced by training, and favorable influences on health (with average scores of approximately 4 on the Likert scale), and the lowest values are allocated to neglecting school activities and the feeling of physical superiority compared to athletes from other disciplines. For this factor, the lowest average score is >3, which is higher than the average value of the Likert scale; as a result, all the effects/benefits of the game of rugby are evaluated as having high importance.

The free answers provide complementary information to the items based on closed answers because they allow the identification of particular problems and issues, related to the characteristics and specificity of the investigated groups. The percentages corresponding to each answer option (associated with the eight items with free answers) indicate differences between the opinions expressed by the two groups; hence, this aspect validates the last hypothesis (H2.2).

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11,

Table 12,

Table 13 and

Table 14 summarize the main variants of free answers, with the percentages allocated to each group and cumulated for the whole group. The data presented above (in connection with the factor analysis) confirm the adequacy of the sampling for analysis, while the good inter-item correlations for the two factors of the questionnaire, for each factor of the questionnaire, and the distribution of the items of each factor by component confirm the hypothesis H1.1.

The reasons that rugby is attractive for these age groups are numerous, but the masculine characteristic is the highest-ranked factor (with over 50% of answers), followed by hard physical contact (over 32% at the level of the whole group, but with dominance for the U-16 group with 41%). The unique character has values of over 30% at the level of the whole group but is dominant for the U-15 group (40%). The existence of collaboration and the higher level of fair play and discipline have lower values for the whole group, but higher percentages for the U-16 group.

Over 40% of players did not practice or currently practice another sport, with a higher percentage for the U-15 group (50%), which is problematic because multilateral training may have beneficial effects on the motor skills of players and facilitate the reorientation of sport in the event of rugby failure. Other sports games ranked highest among the variants practiced for the whole group (over 30%), followed by contact sports (18%), bodybuilding/fitness types, and tennis and athletics, with higher values for the U-16 group and lower values for the U-15 group.

The area with the most problems related to injuries is the legs (over 83% in the whole group), followed by the arms (over 30%), the back and spine (18%), and the head with more than 14%. However, the cause for concern regarding the head and face is that 25% of those with problems are in the U-15 group, similar to abdominal problems. For the rest of the listed regions, the U-16 group has higher percentages of injuries, and those who have never been injured (only 4.8%) were in the U-15 group.

The main cause of injuries is identified as blows and contact with opponents, as a peculiarity of the game of rugby (over 57%), followed by poor warming-up (over 32%), forcing the amplitude of motion (22%), the execution of unconsolidated procedures/poor technique (over 14%), and only 10.20% report excessive loads during training, which shows that the extent of effort is still properly planned. The U-16 group has higher percentages for the entire category of listed factors.

The most difficult aspect for young players to bear is related to the hardness of physical training (over 61% for the whole team, with an increase to over 75% for U-16). Routine and standardized/pattern/workouts are reported by 14.28% of the whole group, but with higher values in the U-15 group (25%), so the ability to concentrate and engage in uninteresting/unattractive and rigid activities for this age category it is more limited. However, 35% of the U-15 players are satisfied with absolutely everything that is planned in training, compared to the U-16 group with only 17%.

The specialization of positions is obviously at a higher level for the U-16 group (almost 90%), with only 10% of these players still being in the test/testing phase. For the U-15 group, the values of specialization of positions are naturally lower (only 80%), and 20% of the players are in tests.

Regarding the ability to self-assess strengths in training, for the whole group, the opinion that the level of specific physical training/fitness is the best-developed skill dominates (over 71%), followed at a great distance by the quality of training/technical skills (47%) and tactical ones (over 20%). The superior values of the U-16 group are noticeable for all these factors of sports training, but especially for the technical and tactical skills.

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicate mismatches in opinion between these two groups for the MS and EB factors. However, from a statistical point of view, these are significant only for two items: MS5/financial motivation in rugby and EB8/utility and accessibility for an active lifestyle, for which Hypothesis H2.1 is validated. For both groups, the average scores of the Likert scale exceed the average limit of 3; scores over 4 are registered for certain items, which emphasize the importance of the motivational factor and the effects/benefits of the game of rugby for the participants in the study. The free answers allowed for additional information about the characteristics of this sport’s attractiveness, being involved in other sports disciplines, and in parallel, the matter of injuries in various parts of the body and their causes, aspects difficult to tackle during training, the self-perceived strong points, and the issues that need to be dealt with. Several studies are analyzed in this chapter to compare the results of our research, in order to identify similar or divergent points.

The effectiveness of consulting rugby players (as research partners in the university environment/colleagues) was demonstrated in a previous study [

54]. They made an important contribution to the construction of a questionnaire aimed at assessing their health, noting superior involvement, additions and improvements for standardized items or those with free answers, and suggestions about their own experiences, similar issues also encountered in our study.

The risk of losing talented rugby players (U-14, U-15, U-16/South Africa) due to RAE (relative age effects) is identified by [

55], noting that grouping by age categories (depending on the date of birth) is often erroneous due to the major differences that often occur between chronological, biological, and psychological age and individual motor potential. Other authors propose a system for identifying and developing young rugby players in the UK who mature later through programs for late-maturing players within the young rugby league, with this facilitating a larger selection base, according to [

56]. Our research also identifies problems related to excessively intense training sessions, which are not adapted to biological age and training level; from technical and tactical points of view, weak points that need improvement have been highlighted.

The financial impact and exodus of South African rugby players to other countries (as a business model) were investigated by [

57]. Financial investments are needed in this sport, in order to prevent the exodus of players to other countries, an aspect also valid in Romania where the weak media coverage and insufficient financial support do not allow a significant expansion of this sport among young people. In our study, financial motivation is significantly more important for the U-16 group.

Unrealistic predictions of young rugby players about the longevity of their sports careers, but also the poor support of clubs and academies, are inhibitory factors for career and post-career planning. Sacrificing the education provided by schools and the exclusive search for financial contracts are mistakes that many young players make, neglecting the concern for other alternative and realistic careers for those who fail in rugby [

58]. Our study identifies more significant issues, related to neglecting school activities, for the U-15 group. The role of rugby players models dedicated to young British players (U-13 and U-14) is captured by [

59]. Almost everyone selected a favorite model/player, chosen for physical skills, technical skills, and temper, aspects also confirmed by our research, with higher scores for the U-15 group.

Attractive training options generate better motivation for young people in rugby. After the implementation of a 24-week program based on TGFU (Teaching Games for Understanding) for U-12 players, the authors found increased learning through cooperation and effort, decreased attitudes of rivalry and inequality, conscious involvement, and a positive attitude towards rugby, according to [

60]. Our study identified a lack of interest in monotonous and stereotypical activities in the U-15 group.

Motivation is influenced by the interaction style of the coach, which must be seen as a source of support to meet the needs of athletes [

61,

62], as also confirmed by our study. Coaches who offer rugby players options and the opportunity to get involved in decision-making will have a positive influence on how competent and autonomous athletes feel. Relationships are perceived as being of high quality for athletes who feel that coaches care and are interested in them, rather than just the results. We have obtained high scores for the importance of victory, which proves that pressures of results also exist for these age categories, with higher values for the U-15 group.

A study conducted on young Spanish rugby players (15–19 years old) identified the importance of the models offered by parents and their role/influence in playing the game in the early years, but also draws attention to the low popularity in the media [

63], a situation similar to the state of rugby in Romania. The parents of young rugby players are advised to constantly talk to them about their wishes and needs and to provide them with the support they need [

64]. The study of 314 boys in England (average age of 16.23 years) showed positive associations between parents’ receptivity to youth prosperity/vitality and negative associations between parents’ receptivity to athletes’ anxiety and anxiety levels before and after competitions, mediated by self-esteem. However, we obtained lower values of motivation to play rugby from parents/entourage, but higher values associated with the influence of the coach.

Differences in the motivational factors for rugby players are reported depending on gender. Even if both genders have high scores for intrinsic motivation, the tendency of men to orient themselves towards external rewards (extrinsic rewards) is indicated, and the component related to the social aspect is very important, according to [

65], an aspect confirmed by our study for the U-16 group.

Interviews with rugby coaches (for U-13 groups) conducted by [

66] point out that early specialization is not indicated, with less than 25% of children from the U-13 group found in U-18 groups and late specialization (high school) being indicated, while in the U-16 group, one can move on to talent identification when physical maturation indicates the presence or lack of qualities for rugby. In our study, 90% of the U-16 group already have a clearly defined specialization. Maintaining a larger group of young athletes is important, rather than just small elite groups. Attempts at several branches of sport in the U-13 group are recommended to diversify motor skills. In our study, 50% of the sportsmen in the U-15 group and 62% of the U-16 group practice other sports disciplines, where other sports games are prevalent. The pressure of results at a young age should be avoided, and the provision of sufficient time for homework should be allowed, as the issue of motivation related to victory and neglect of schoolwork (especially for the U-15 group) is also reported in our study.

The problems generated by the early selection and over-specialization, as well as the important role of the coach in the education and motivation of young players in understanding their needs related to the development phases, are also signaled by [

67]. The need for a multidimensional/holistic assessment of talented young rugby players in Australia is highlighted by [

68], which insists on investigating the real potential (physical performance, anthropometric measurements, technical-tactical skills, mental traits, etc.) as a way to minimize RAE (relative age effects), a topic also highlighted by [

69].

Knowing the mental, motor, and physical characteristics of the players allows trainers to individualize and adapt the training process. The comparative study of young players (16 years old) in rugby, football, and basketball showed that all specializations have a good ability to manage stress, superior motivation, and self-assessment skills, but those in rugby have better scores related to the evaluation of performance and mental capacity, and those in football to control stress, motivation, and cohesion of the team, according to [

70]. We noted higher scores of favorable self-assessments of their own abilities for the U-16 group.

Attention to injuries in rugby for young people is addressed by [

71], highlighting the hardness and the fact that it is a contact sport (full-contact collision), in which the force to gain possession of the ball is often extreme. Young people and children are more prone to injuries due to physical vulnerability; our study shows that most injuries are caused by direct contact with opponents, even if this is a particular attraction of rugby.

Players with high workloads and training throughout the season recovered faster than those with moderate or low values. The analysis of shorter stages (intense competitive phases) generated high levels of stress and poor recovery for those involved more, so not all young people can cope with stress and rapid recovery processes, which can affect results, cause injuries, and result in overtraining, according to [

72]. It is recommended to reduce the intensity of the effort on the day when rugby players report, in the morning before training or competition, an impairment of well-being, so as not to diminish performance, according to [

73]. Our group indicates physical training and hard effort as the main aspect that is difficult to bear in training.

Using/wearing mouth guards (MGs) in adult rugby players of Japan is conditioned by their use during the high school period, as a measure of reducing injuries in this area of the body [

74].

Concussions can cause long-term neurological complications. Even though 91% of rugby players surveyed know they do not have to play anymore, 75% will continue to do so after a concussion, with men less worried about the long-term effects [

75]. A study of Irish rugby players (U-20) found that almost 50% had suffered a concussion at least once, but the problem is that they do not understand the risks associated with the lack of medical investigation after suffering this trauma, and efforts are needed to inform players to reduce the risk of future secondary injuries [

76]. A study performed on 304 young rugby players in Ireland (12–18 years old) a decade ago reports a concussion incidence of 6.6%, and 25% of them return to play on the pitch without seeking advice or consent from a doctor. The explanation offered is the internal motivation and the desire to play, which put pressure on the athletes, according to [

77]. In our research, we discovered a high frequency of injuries to the legs and arms, with blows to the head and face being more frequent for the U-15 group.

The simultaneous existence of the well-being of professional rugby players in England (athlete welfare) and high sports performance is conditioned by the existence of several factors that generate prosperity (enhance thriving): Quality and strengthened relationships with teammates, good relations between players, coaches, and club management, activating an integrated, inclusive, and trustworthy environment, identifying the sensitive points of the players, and carefully treating families and players who do not always play or belong to the reserves. All these factors ensure development and success, according to [

78]; our study also highlighted the importance of qualitative relationships with teammates and the coach in order to facilitate performance.

5. Conclusions

This study validates the hypotheses regarding factor analysis and the internal consistency of the constructed and applied questionnaire and identifies the differences in opinions on the items with free answers. However, the analysis of variance showed that the differences between the scores of the two groups are, in most cases, insignificant (the values of F correspond to the threshold p > 0.05). Exceptions are observed only in the case of two items: Financial motivation (where those in the U-16 group have significantly higher scores, being more concerned about this aspect) and accessibility/usefulness of rugby for the population, as a variant of active leisure (where those in the U-15 group are significantly more optimistic). The U-15 team is more attracted to the top players in terms of role models, more involved in training out of passion, and also more dependent on the quality of relationships with the coach and teammates (with the coach having an important role in supporting and motivating young people), while those in the U-16 team have better scores on self-perceived skills that ensure success in rugby. Surprisingly, however, parents and entourage have much lower scores than coaches, in the motivational support for this sport. The U-15 team has a more optimistic perception of most of the benefits of rugby on multiple levels, and those in the U-16 team have higher scores on favorable effects on attitudes and better manage problems related to school activity, managing to focus better on both levels (academic and sports). The fact that 80% of the members of the U-15 group and 90% of those of the U-16 group already have a specialization in a playing position is a gratifying aspect, which can be explained by the fact that their level of training is higher (by comparison with their colleagues from their clubs of origin).

The masculine characteristics of the game, its uniqueness, and the physical contact are the main factors of attraction for rugby. Over 56% of players have practiced or currently practice other forms of movement, with sports games and contact sports being favorites. Moreover, 96% of the players suffered injuries, with their legs and arms being the most affected, but the high incidence of head and face blows for those in the U-15 group (25%) is surprising, with the main causes for these problems identified as the hardness of the contact with opponents and the superficiality of warming up. Hard, intense, and long workouts (related to physical training) are the most difficult factor to bear, and for the U-15 group, the boredom induced by routine and monotony is noted. However, the high level of physical training/fitness is self-perceived as the main strength of the players, followed by technical and then tactical.

Practical Applications

The results obtained can be used by coaches to optimize the training process by capitalizing on the motivational components identified and eliminating the problems identified by athletes. Trainers can adjust/adapt their behavior and support their players much better, as the relationship between them and the players is emphasized as being relevant for obtaining superior performance. Ensuring a collaboration framework within the group is also important in order to increase both the involvement and the level of self-confidence. Promoting the game within schools and for young people should be based on the aspects that render it attractive (the unique aspect, the man-like aspect, and the high level of fair play). The study also provides relevant information about the options that can reduce boredom and put an end to abandonment, that is, avoiding standard, monotonous training and promoting interesting activities for these age categories. The fact that the players indicate the causes generating injuries frequently represents an opportunity for the prevention and treatment of the non-superficial warming-up stage in training. Focusing on exercises/mobility structures that have beneficial effects on the muscle force and the mobility of the inferior member joints (where most injuries are observed) is a priority. Last but not least, the fact that the players mention a series of training weak points that they consider to prevent them from optimizing their performance might provide guidance and personalization of training by improving these problematic factors.

Limits of the study and future directions of investigation:

The studied scientific literature also includes other research directions, which are missing in our study. We did not address the issue of addictions (especially smoking, but also alcohol and banned substances/doping among rugby players and coaches), an aspect reported by [

79], as well as high-risk health behaviors.

The investigation of the coaches working in club teams and in national groups for the questioned age ranges would facilitate a more complete study, providing information related to the investigated issue. Furthermore, questioning athletes in senior teams would identify how to change the perception of the motivational factor and assess the effects of the game of rugby, with increased age and increased competitive experience.

A differentiated analysis of players’ skills in positions and departments would allow a clearer orientation of training, as the investigation of [

80] establishes that attackers have better scores for agility tests, and upper body strength is very important for defenders/back players. The analysis of variations and fluctuations in the physical development and motor skills of school rugby players at puberty and adolescence (for close age ranges) would be another direction to investigate, in order to eliminate some of the problems generated by the relative age of athletes, a problem also reported by [

81].

Last but not least, a comparative approach between the selection process, the work methodology, and the competitive system in Romania and countries with results and tradition in rugby (Southern Hemisphere and Western Europe) would identify differences that facilitate the achievement of sports performance.