Barriers and Motives for Physical Activity and Sports Practice among Trans People: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

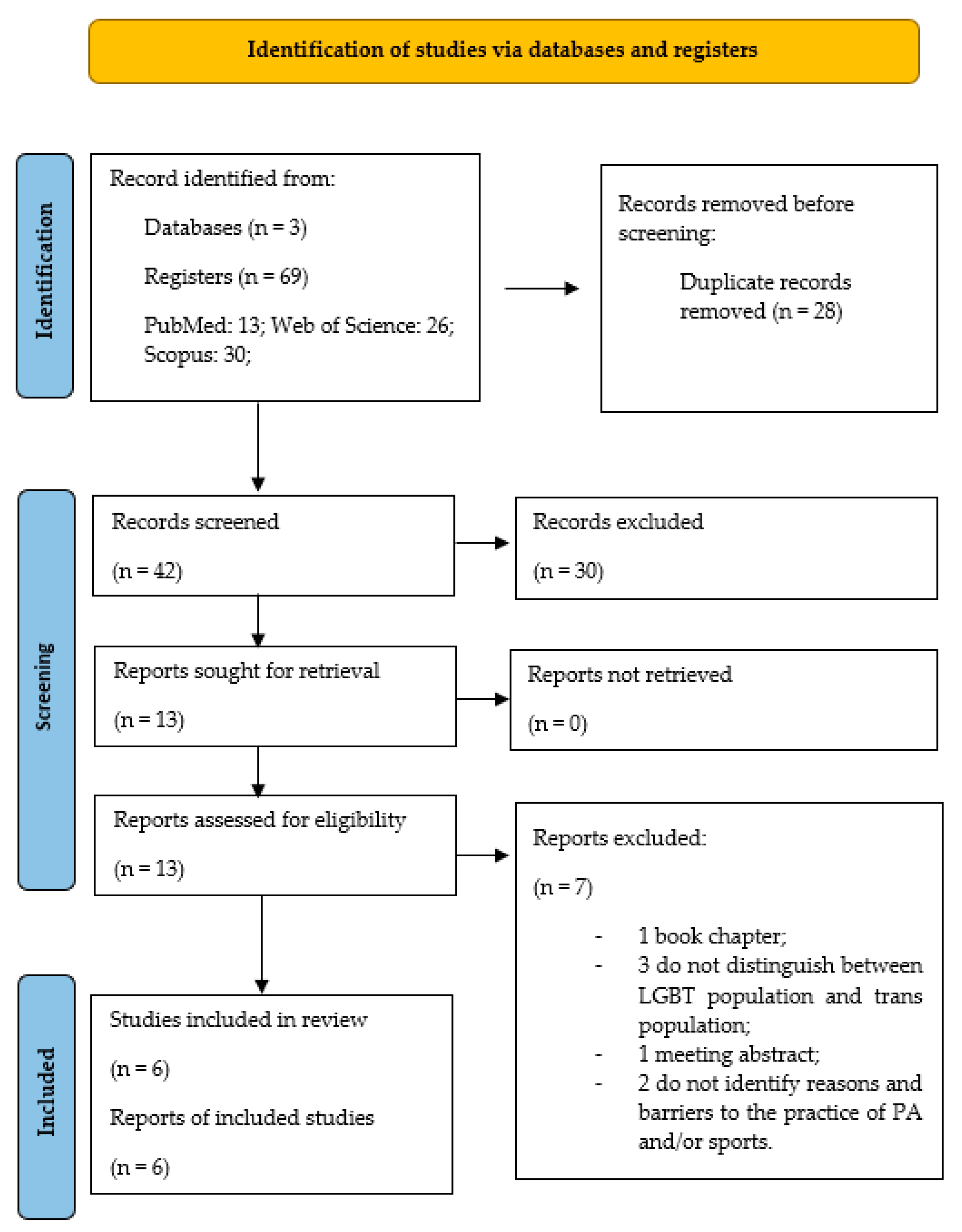

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Selection and Data Collection Process

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychologist Association Guidelines for Psychological Practice With Transgender and Gender Nonconforming People. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 832–864. [CrossRef]

- CoE. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People Introduction to the Guidelines; UCSF: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- WPATH. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People The World Professional Association for Transgender Health; WPATH: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, M.; Adams, N.; Cornell, T.; Kreukels, B.; Motmans, J.; Coleman, E. Size and Distribution of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Populations: A Narrative Review. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 48, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen-Smith, A.A.; Sineath, C.; Sanchez, T.; Dea, R.; Giammattei, S.; Gillespie, T.; Helms, M.F.; Hunkeler, E.M.; Quinn, V.P.; Roblin, D.; et al. Perception of Community Tolerance and Prevalence of Depression among Transgender Persons. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2017, 21, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lombardi, E.L.; Malouf, D. Gender Violence: Transgender Experiences with Violence and Discrimination. J. Homosex. 2001, 42, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemmer, C.L.; Arayasirikul, S.; Raymond, H.F. Transphobia-Based Violence, Depression, and Anxiety in Transgender Women: The Role of Body Satisfaction. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 2633–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisner, S.L.; Poteat, T.; Keatley, J.A.; Cabral, M.; Mothopeng, T.; Dunham, E.; Holland, C.E.; Max, R.; Baral, S.D. Global Health Burden and Needs of Transgender Populations: A Review. Lancet 2016, 388, 412–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderssen, N.; Sivertsen, B.; Lønning, K.J.; Malterud, K. Life Satisfaction and Mental Health among Transgender Students in Norway. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bouman, W.P.; Claes, L.; Brewin, N.; Crawford, J.R.; Millet, N.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Arcelus, J. Transgender and Anxiety: A Comparative Study between Transgender People and the General Population. Int. J. Transgenderism 2017, 18, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, S.L.; Adelson, J.L.; Howard, K.A.S. Anxiety and Depression in Transgender Individuals: The Roles of Transition Status, Loss, Social Support, and Coping. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 81, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Connolly, M.D.; Zervos, M.J.; Barone, C.J.; Johnson, C.C.; Joseph, C.L.M. The Mental Health of Transgender Youth: Advances in Understanding. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J.K.; Doty, J.L.; Catalpa, J.M.; Ola, C. Body Image in Transgender Young People: Findings from a Qualitative, Community Based Study. Body Image 2016, 18, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witcomb, G.L.; Bouman, W.P.; Brewin, N.; Richards, C.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Arcelus, J. Body Image Dissatisfaction and Eating-Related Psychopathology in Trans Individuals: A Matched Control Study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2015, 23, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ellis, S.J.; McNeil, J.; Bailey, L. Gender, Stage of Transition and Situational Avoidance: A UK Study of Trans People’s Experiences. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2014, 29, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malm, C.; Jakobsson, J.; Isaksson, A. Physical Activity and Sports—Real Health Benefits: A Review with Insight into the Public Health of Sweden. Sports 2019, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Mello, M.T.; Lemos, V.D.A.; Antunes, H.K.M.; Bittencourt, L.; Santos-Silva, R.; Tufik, S. Relationship between Physical Activity and Depression and Anxiety Symptoms: A Population Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 149, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carek, P.J.; Laibstain, S.E.; Carek, S.M. Exercise for the Treatment of Depression and Anxiety. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2011, 41, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ströhle, A. Physical Activity, Exercise, Depression and Anxiety Disorders. J. Neural Transm. 2009, 116, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, J. Exercise and Cardiovascular Health. Circulation 2003, 107, e2–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinckard, K.; Baskin, K.K.; Stanford, K.I. Effects of Exercise to Improve Cardiovascular Health. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Nicol, C.W.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health Benefits of Physical Activity: The Evidence. CMAJ 2006, 174, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elling-Machartzki, A. Extraordinary Body-Self Narratives: Sport and Physical Activity in the Lives of Transgender People. Leis. Stud. 2017, 36, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storr, R.; Nicholas, L.; Robinson, K.; Davies, C. ‘Game to Play?’: Barriers and Facilitators to Sexuality and Gender Diverse Young People’s Participation in Sport and Physical Activity. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.A.; Haycraft, E.; Bouman, W.P.; Arcelus, J. The Levels and Predictors of Physical Activity Engagement within the Treatment-Seeking Transgender Population: A Matched Control Study. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muchicko, M.M.; Lepp, A.; Barkley, J.E. Peer Victimization, Social Support and Leisure-Time Physical Activity in Transgender and Cisgender Individuals. Leis. Loisir 2014, 38, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudzynski, L.; Ebben, W.P. Original Research Body Image as a Motivator and Barrier to Exercise Participation. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2010, 3, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- López-Cañada, E.; Devís-Devís, J.; Pereira-García, S.; Pérez-Samaniego, V. Socio-Ecological Analysis of Trans People’s Participation in Physical Activity and Sport. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2021, 56, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, C.; Sbaraglia, M.; Hillier, L.; Mitchell, A. Come Out to Play: The Sports Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender LGBT) People in Victoria; Institute of Sport, Exercise and Active Living: Sydney, Australia, 2010; ISBN 9781921377860. [Google Scholar]

- Hargie, O.D.W.; Mitchell, D.H.; Somerville, I.J.A. ‘People Have a Knack of Making You Feel Excluded If They Catch on to Your Difference’: Transgender Experiences of Exclusion in Sport. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2017, 52, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Samaniego, V.; Fuentes-Miguel, J.; Pereira-García, S.; López-Cañada, E.; Devís-Devís, J. Experiences of Trans Persons in Physical Activity and Sport: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, J.; Hirschberg, A.L.; Jose, M.; Patino, M.; Ritzén, M.; Vilain, E.; Partner, J.T.; Bird, B.; Riley, L.; Thill, C. IOC Consensus Meeting on Sex Reassignment and Hyperandrogenism; IOC: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Human Rights Commission. Guidelines for the Inclusion of Transgender and Gender Diverse People in Sport; Australian Human Rights Commission: Sydney, Australia, 2019; ISBN 9781921449932. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association Transgender Exclusion in Sports. Available online: https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/policy/issues/transgender-exclusion-sports (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A Comparison Study of Specificity and Sensitivity in Three Search Tools for Qualitative Systematic Reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nang, C.; Piano, B.; Lewis, A.; Lycett, K.; Woodhouse, M. Using the PICOS Model to Design and Conduct a Systematic Search: A Speech Pathology Case Study; Edith Cowan University: Perth, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, M.; McClearen, J. Transgender Athletes and the Queer Art of Athletic Failure. Commun. Sport 2020, 8, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, M.; Wallach, P.; Kyriakou, A. Levels of Physical Activity and Barriers to Sport Participation in Young People with Gender Dysphoria. J. Pediatric Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 34, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.A.; Arcelus, J.; Bouman, W.P.; Haycraft, E. Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity and Sport Participation among Young Transgender Adults Who Are Medically Transitioning. Int. J. Transgenderism 2017, 18, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, C. Thinking beyond the Binary: Barriers to Trans* Participation in University Sport. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2021, 56, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, L.; Oates, J.; O’Halloran, P. “My Voice Is My Identity”: The Role of Voice for Trans Women’s Participation in Sport. J. Voice 2020, 34, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Teti, M.; Bauerband, L.A.; Rolbiecki, A.; Young, C. Physical Activity and Body Image: Intertwined Health Priorities Identified by Transmasculine Young People in a Non-Metropolitan Area. Int. J. Transgender Health 2020, 21, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.A.; Arcelus, J.; Bouman, W.P.; Haycraft, E. Sport and Transgender People: A Systematic Review of the Literature Relating to Sport Participation and Competitive Sport Policies. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López-Cañada, E.; Devís-Devís, J.; Valencia-Peris, A.; Pereira-García, S.; Fuentes-Miguel, J.; Pérez-Samaniego, V. Physical Activity and Sport in Trans Persons before and after Gender Disclosure: Prevalence, Frequency, and Type of Activities. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, G.B.; Buzuvis, E.; Mosier, C. Inclusive Spaces and Locker Rooms for Transgender Athletes. Kinesiol. Rev. 2018, 7, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, B.A.; Haycraft, E.; Murjan, S.; Arcelus, J. Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating in Trans People: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miller, A. International Policy Review 2021 Sceg Project for Review and Redraft of Guidance for Transgender Inclusion in Domestic Sport 2020; SCEG: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Carraça, E.V.; Markland, D.; Silva, M.N.; Ryan, R.M. Exercise, Physical Activity, and Self-Determination Theory: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Search Strategy | (“transgender” OR “transsexual” OR “trans individual” OR “trans people” OR “gender identity disorder” OR “gender dysphoria” OR “gender disclosure” OR “gender non-conforming”) AND (“physical activity” OR “exercise” OR “sport”) AND (“barriers” OR “obstacles” OR “facilitators” OR “determinants” OR motiv*) |

| Author | Aims | Participants | Type of Study | Methodology | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fischer and McClearen [38] | Examine how Fox’s expression of the queer art of failure provides space for rupture in racialized, hypermasculine, and heteronormative sporting spaces by finding liberation through failure. | N = 1; Professional mixed-martial-arts (MMA) fighter | Case study. | Queer methodology (combines multiple methods—interviews and critical discourse analysis). Duration: 60 min | Barriers to MMA:

|

| Gilani and colleagues [39] | Determine the levels of physical activity (PA) in young people with gender dysphoria (GD) and help identify factors that deter participation. | N = 55; AA: 16.3 Y On treatment with GnRH analog therapy. | Mixed-methods study. |

| Main barriers:

|

| Jones and colleagues [40] | Understand what factors are associated with physical activity and sports engagement in young transgender adults who are medically transitioning. | N = 14; (Transgender male = 9, transgender female = 5) AA: 22.71 Y (range 18–36). | Qualitative study. | Semi-structured interviews; Duration: 15 to 37 min | Internal/personal barriers:

|

| Phipps [41] | Outline perceptions of trans * inclusion in university sport, focusing particularly on binary models of gender evident in the BUCS transgender policy and the wider provision of sport. | Not reported. | Qualitative study. | Interviews with focus groups; Duration: 45 to 60 min. | Barriers:

|

| Stewart and colleagues [42] | Explore trans women’s experiences and awareness of their vocal communication and voice use within sporting environments. | N = 20 (all transgender female); Range: 16–65 Y All participated in organized sports, identify as trans women, and have either fully socially transitioned or are in the process of transitioning to live as a female. | Mixed-methods study. |

| Main barriers:

|

| Teti and colleagues [43] | Explore body image and exercise as priorities among transmasculine young people (TYP). | N = 16 (all transgender male); Range: 19–25 Y; Without any surgical interventions or procedures. | Qualitative study. | Semi-structured interviews. Duration: 60 min | Barriers:

|

| Internal | Body dissatisfaction and body discomfort; gender incongruence; fear and anxiety about others’ reactions and possible discrimination; inability to reconcile as an athlete and a trans woman; the constant need to prove womanhood; lack of clear guidance; negative past experiences; voice. |

| External | Lack of safe and comfortable spaces; inadequate changing facilities; sport-related clothing; team policies, rules, and regulations surrounding gender; popular discourse on the science of sex and race. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliveira, J.; Frontini, R.; Jacinto, M.; Antunes, R. Barriers and Motives for Physical Activity and Sports Practice among Trans People: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095295

Oliveira J, Frontini R, Jacinto M, Antunes R. Barriers and Motives for Physical Activity and Sports Practice among Trans People: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095295

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira, Joana, Roberta Frontini, Miguel Jacinto, and Raúl Antunes. 2022. "Barriers and Motives for Physical Activity and Sports Practice among Trans People: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095295

APA StyleOliveira, J., Frontini, R., Jacinto, M., & Antunes, R. (2022). Barriers and Motives for Physical Activity and Sports Practice among Trans People: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 14(9), 5295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095295