2. Emerging Themes

The papers in this Special Issue reflect a range of issues and geographies. There are two papers from the global South (specifically from middle-income, settler post-colonial and climatically temperate sites, viz. Cape Town in South Africa and Chile) and five from the global North (or more specifically, four from the UK and one from north west Europe). Two deal with transport, one with housing, one with sanitation, and three with cross-sectoral local governance of climate issues. Their objects range in scale from the hyper-local to the megacity and the cross-boundary.

Nevertheless, several core themes strongly emerge from the collection. We hope that, in reading them, you will agree with us that together these articles do an exemplary job of illuminating these themes with practical insight and purpose. They will be of use not just to researchers, but to people working in and with local authorities on climate governance—again, at least across the democratic global North and ‘near-North’. By highlighting some of the features of their everyday experience and exploring their causes and connections, we hope that this collection might suggest some practical ways forward to diverse readers. However, the Special Issue also draws attention to differences as well as similarities across places, and the need for sensitivity to situational specificity.

First, the most prominent shared theme is the need for institutional and, indeed, constitutional change: the present emerges clearly as a moment, akin to the early 19th century in Europe, in which the political imperative is one of reform and re-establishment of state settlements, particularly regarding relations between national and sub-national/local government. The papers consistently describe a lack of integration or coordination between formal and informal governance actors on a vertical scale, i.e., between national, regional and local tiers of government and their partners, and a concomitant lack of strong national leadership. They also describe a lack of horizontal coordination and integration, i.e., a fragmentation of interests, action and understanding between governance organisations operating on or within the same spatial scale, and with other stakeholders and publics. They even identify such fragmentation occurring within organisations, particularly local authorities.

The picture that emerges from these papers is thus of an inconsistent patchwork of approaches, developed piecemeal in different territories and scales, both top-down and bottom-up, and characterized by a proliferating and fissiparous complexity. What it is not, therefore, is a coherent framework. The lack of scalar and sectoral coordination and transparency both inhibits effective action, and enables inaction and blame-shifting. This feeds the further proliferation of fragmenting and overwhelming complexity, as opposed to integrated and unified direction. The local is often lionized both in the academic literature on governance, and in policy and practice, and as these papers demonstrate, some local and bottom-up action is possible. However, this is highly variable across scales and territories, and is fragile and open to disruption. It is clear that ‘the local’ is per se no more pragmatic, or less political and fractious, than any other scale.

Moreover, even to the extent national government is coming around to accept and even proselytise more local powers, this tends to take a form that militates against its effective realisation. Instead, national government tends to continue to hold tight to the reins of power, while perhaps doling out limited powers and ring-fenced pots of money through specific and competitive policy initiatives that come with significant strings attached [

9,

10]. Certainly, this is the current situation in the UK, as recent announcements regarding the actual form of the flagship manifesto policy of ‘levelling up’ the regions (specifically the north of England vs. London), and associated (limited) devolution, has illustrated [

11].

The papers as a collection thus make a significant contribution to the argument that constitutional change is required to establish consistent national approaches to, and coherent sub-national and cross-sectoral distributions of, powers, responsibilities, accountability and funding for the unprecedented governance challenge of climate action. Devolution and a focus on the local are often touted as solutions to governance problems. However, another theme emerging from this collection of papers is that simple devolution may simply lock in existing inequalities and feedback loops. This is illustrated at wide range of scales, from the international to the hyper-local. Or, to put this the other way around, the nation-state and national scale also remains crucial, if in need of significant reshaping and reorientation.

The papers which consider cases in the global South are concerned with the urgency of increasing resilience and adaptation to the consequences of climate change, reflecting their status as communities which are most vulnerable to those impacts. Meanwhile those examining cases in Europe, in communities that are less vulnerable, are able to focus on the challenges of decarbonisation in various ways. This includes, illustrated in parish councils in one county in England, a wide range of responses—or absence of response—to the climate emergency. Several papers illustrate the potential for generating change and momentum at a local level, but also the fragility of this in the face of structural challenges; structural challenges to which national (and thence inter-national) government alone can effectively respond. Interventions need to recognise the existing capacities of places for constructive or destructive feedback loops, and the need for cohesion and solidarity at a higher level. A strategic and coherent trans- or multi-scalar governance approach is needed at international, national and sub-national scales to intervene in already-existing inequalities and to prevent positive feedback loops exacerbating cycles of inequality.

However, while the papers illustrate the vast gap between current situations and the kind of practices and institutional structures that might be needed for effective governance in a climate emergency, they also offer glimpses of hope in already ongoing practices. The potential for doing things better is clearly visible in the seeds of practical action that are already being sown, with insights into how things have been, are being, and could be done, at the level of local governance specifically.

Locally led, independent climate action is being driven variously from the (local) top down and the bottom up in different locations. However, these steps in the right direction are tentative and fragile, lack coordination or strategic connection, and are subject to disruption in the absence of a new constitutional settlement vis-à-vis the nation-state that would provide a more nurturing environment for them. However, although the papers make a collective case for a more coherent approach to sub-national climate action, they also recognise the need for flexibility, for local specificity and response-ability to specific local situatedness. What emerges therefore is not a clear picture of what coherence looks like, but rather the need for transparency, clarity, and cross-sector, cross-scalar co-operation in its very development. What also emerges, at the very least, is a call for urgent discussion, public and scholarly, and experiment on such constitutional issues as a key pillar of climate action, not a rabbit-hole distraction from it.

Yet, secondly, there is also a pragmatic emphasis across the papers on starting from where we find ourselves now. Certainly, the points just made regarding constitutional and institutional reorganization must not be read as the forlorn demand that ‘we shouldn’t start from here’. Indeed, amidst all the complexity that characterises local government/politics today, one may be moved to ask how such constitutional resettlement could even be attempted without simply making matters even more complex and, hence, intractable. A pragmatic approach demands recognizing that institutional change does not generally happen quickly, not least because of the intrinsic ‘self-cementing’ dynamics of (governmental) power relations. Yet, the argument remains unequivocal across the papers that existing institutional structures are not well-suited to tackling the climate emergency, and that this suboptimal present embeds a host of complicated and often unhelpful power relations.

If this is not to be simply a cause of despair, it follows that there is no option but to work with the situations and power relations which actually exist, and the webs of interests, priorities, conventions and norms that that implies. Many of the papers also offer, explicitly or implicitly, an understanding that the futures we move towards will also thus be suboptimal, at least partly because we do not know in advance what an optimal future might look like. However, this should not prevent us from building on the present seeds of hope towards an end (e.g., a net-zero-carbon future) that is at once both desirable and open or indeterminate. It is possible, even desirable, to acknowledge uncertainty about a future end state and still take steps towards it, with a view to learning more about both the destination and how to reach it on the way. Moreover, the goal or challenge thus emerges clearly as reforming the institutions and settlements of local government in parallel with continued action by local government on climate, rather than the seemingly rational approach of first getting the former ‘right’.

Thirdly, then, many of the papers also identify, explicitly or implicitly, specific factors which enable and constrain rapid climate action. This, in a way, also provides reasons for hope, as it allows for practical learning from existing situations in order to adapt and adjust as institutions move forward. While not providing a route map to a net-zero-carbon future, let alone a (utopian?) blueprint of that destination, they may provide something akin to a compass direction. They offer a clear-eyed assessment of the challenges, and a means of understanding and thus navigating through them from within. There is also a recognition that these understandings are situated—the factors that enable and constrain action are not universal and will depend on local specificity. Here, the diversity of cases also helps, providing a means for actors to sensitise themselves to unfamiliar situations and perspectives, and hence to the potential for action, and with much more work to be done in this regard in future research.

Good (and bad) practice can be (and are already being) identified and learned from, along with the causes and influences on those practices and their effects. Again, practices are specific responses to local situations, so lessons from them should be contextualised as inputs that sensitise rather than universal applications: insights generated in one site can suggest possibilities for the attention, analysis and intervention of researchers and practitioners elsewhere, rather than indicating the desirability of the wholesale transfer of practices [

12]. The value of learning, and continuing to learn, —and hence, in turn, learning

how to learn, or what Bateson referred to as ‘learning 2′ [

13]—from these examples cannot be over-emphasised, and both individually and collectively/institutionally. A crucial lesson that we have drawn from this process is the need to understand institutional dynamics better in relation to climate governance, and the importance of investing in institutional capacities to engage in processes of ongoing learning.

3. Phronesis—The Vital Missing Piece

There is, therefore, considerable insight and agreement across the papers that follow. Yet, what arguably remains missing is a terminology and/or framework that promises to be able to synthesize the wide-ranging points made above into a coherent and readily comprehensible whole. Such coherence, or at least the palpable sense of its immanent and imminent possibility, seems particularly important in the context of the current challenge being not simply climate action (i.e., in all its complexity, existential stakes and urgency) but also climate action.

How, in other words, are all these disparate insights to be held together and easily accessed by those actually tasked with the massive challenge of doing something about expedited and ‘just’ transition [

14]; those who must attend to the concrete detail of actual climate challenges and so cannot spare hours and/or ‘brain space’ for the abstract lessons above, in all

their complexity? How can all these points be condensed—but not ‘reduced’—to a single, memorable and yet productive, enabling idea? Our argument here is that this can indeed be done, and under the terminology of ‘phronesis’.

As detailed in Yuille et al. in this volume [Contribution 1] (and see also [

15]), ‘phronesis’ connotes the situated practical wisdom needed to (learn how to) govern complex dynamics systems well, and hence situated

within such predicaments. It takes its name and inspiration from Aristotle’s primary epistemic virtue. This is the practice and capacity for judgement presupposed by the skilful exercise of the two more familiar forms of knowledge that have dominated the modern age and brought us to our current predicament of global complex systems challenges, namely: episteme, or abstract ‘what/why’ knowledge of ‘natural law’; and techne, or concrete ‘know how’.

Yet, the resurrection of the term has also involved its fundamental redefinition [

8,

16] to incorporate in that ‘situated practical wisdom’ a deliberate attentiveness to issues of differential power relations in which all human agents are necessarily situated at any given place and time. Indeed, drawing specifically on the insights in the later work of Michel Foucault [

17,

18] regarding the inseparability of human power relations and (assertions/deployment of) knowledge, phronesis is thereby expanded and redefined. It becomes ‘situated practical wisdom’ that is both, and simultaneously, always strategic—vis-à-vis attention to those irreducible power relations—

and ethical—regarding the personal sensitivity to questions of truth and value implicit in the designation of beliefs as ‘knowledge’.

In our own contribution to this Special Issue, written without the benefit of having already read and reflected on all the other articles, we foreground and investigate the importance of phronesis for local government climate action in one particular sense. Specifically, we foreground the importance of institutional and personal capacity to learn about how climate action might, and/or does, actually best work in the situated institutional and cultural-political-economic setting in question. In other words, we focus on the strategic dimension of phronesis, and its phronetic learning process.

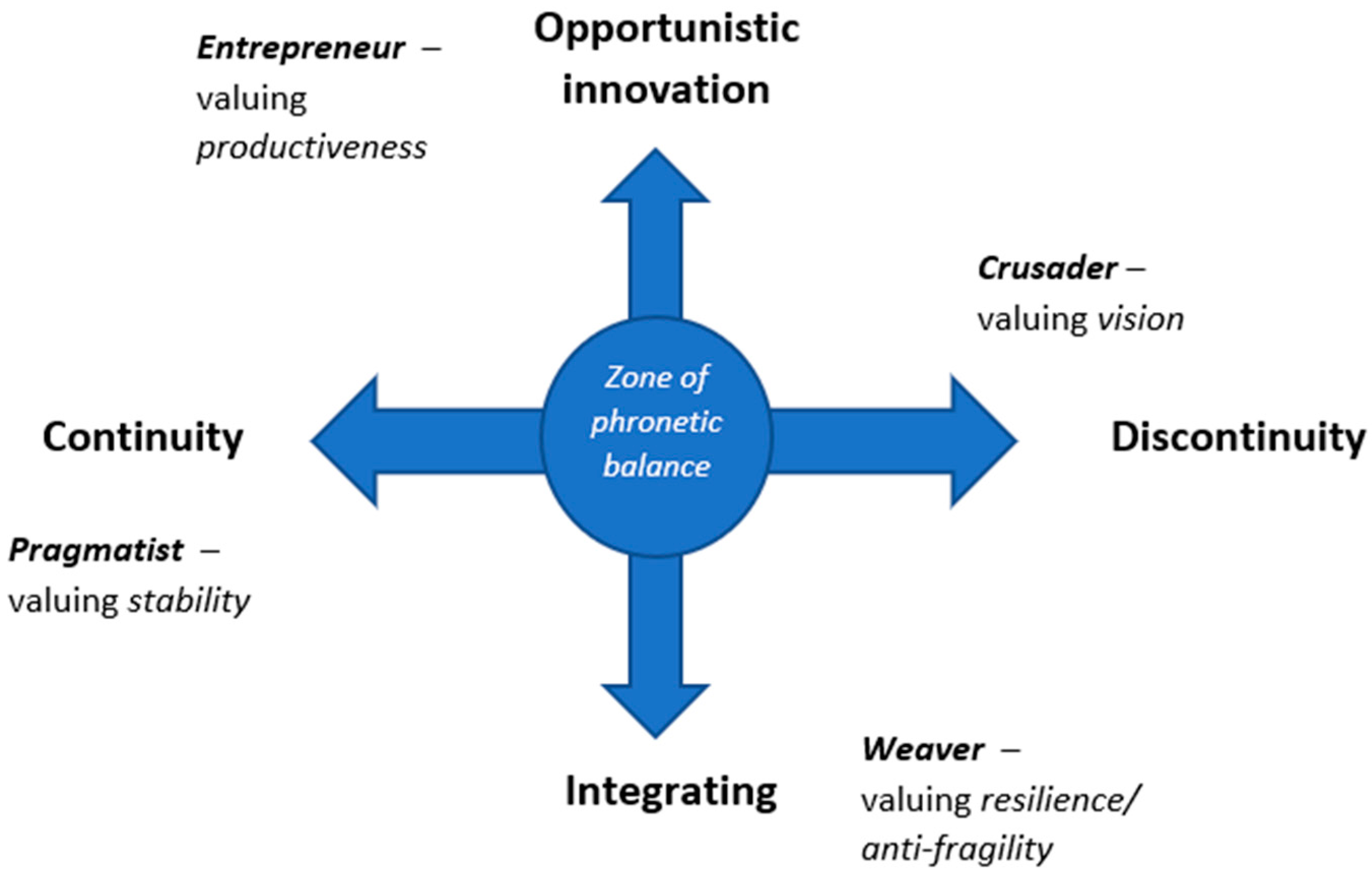

This led us to identify four key roles for effective local government climate action (namely ‘crusaders’, ‘pragmatists’, ‘entrepreneurs’ and ‘weavers’). (For a similar argument from economic geography/regional development literature encountered since writing that article, see [

19]). All four of these roles are crucial, but with one in particular often undervalued and neglected, namely ‘weavers’—see

Table 1 and

Table 2, reproduced from Contribution 1, this volume).

What is brought to light in synthetic reflection on the whole collection, though, is the importance also—if not pre-eminently—of the other, parallel element of ethical dimensions of situated practical wisdom. In short, phronesis emerges across all the papers as the self-conscious practice and orientation to cultivation of ever-greater skilfulness in both strategic and ethical regards, and hence, in turn, to learning about such learning.

As such, there is much more to say about phronesis, what it is and how to do it, and why it is so important—indeed primary, the key missing piece—regarding local government climate action. We do not propose to exhaust this further exploration here, but only to open up this wider agenda for further research.

One way into this broader perspective on phronesis and its importance is via consideration of current climate politics, especially in the global North. Some two years on from the initial efflorescence of ‘climate strikes’ and subsequent declarations of ‘climate emergency’ that prompted this Special Issue—and with the profound changes initiated by the pandemic as well—it is now apparently the case that political consensus regarding the need for (some) climate action is effectively established. Yet, debate has thus simply shifted terrain, most obviously through and after COP26 in Glasgow, towards a new and emergent polarization, broadly between ‘crusaders’ and ‘pragmatists’ regarding the pace and profundity of climate action, in bitter and deepening stand-off. These dynamics are further exacerbated by the looming danger that climate politics is pulled into the ongoing ‘culture war’ of identity politics unfolding across the global North [

20]. Moreover, this emergent political fissure has become palpable in local politics, e.g., regarding ‘low traffic neighbourhood’ plans, thereby furnishing a salutary puncturing of the bubble of fetishized local as supposedly always more productive and harmonious than national politics [

21].

Seeking thus to go beyond this increasingly hostile and obstructive context, one key element of phronesis that emerges into view is the imperative of recognizing the validity of concerns about (or, conversely, valuing) both continuity (pragmatists) and discontinuity (crusaders). A phronetic approach would, rather, move to put both orientations into productive relation.

Viewing

Table 1 and

Table 2 in this light, however, readily suggests a way forward. This relation is formed by the bridging activity of the two other roles, entrepreneurs and weavers. As such, the importance of these two roles is illuminated further. So too is the importance of a reframed approach to addressing the key question of: “how should the operations and institutions of local government be (re-)arranged so that they are more effective in realizing their stated goals of deep, expedited, locally-relevant climate action?”

However, in identifying these bridging roles, and the fact that there are two of them, we also find here a further dimension that needs to be taken up explicitly and then with balance explicitly cultivated in that regard as well. This second dimension concerns a spectrum between the opportunistic, self-starting innovation of the entrepreneur and the integrating work of the weaver. It is thus a spectrum of (individual) action and its priorities. By contrast, the continuity/discontinuity spectrum is also clearly thus one of institutional form and practices.

Closer specification of phronesis therefore precisely illuminates two key dimensions and with the challenge being to cultivate skilful balance in

both, since both ends of their respective spectra are valid and valuable concerns and approaches (

Figure 1, below). Moreover, the present situation is thus elucidated, in that what is missing primarily today is, first, the latter dimension (to bridge the polarized politics of pragmatist/crusader); and then the (re)balancing from opportunistic innovation/entrepreneur to integrating/weaver.

As such, it is emphatically not that weavers are per se primary, as necessary and sufficient condition for effective local climate action; a sort of fundamental capacity or institutional silver bullet. Rather, they are the role amongst the set of all four that is at present systematically neglected and undervalued, and most in need of concerted support, including in terms of investment in institutional capacity for such ‘weaving’ work (both within local government institutions themselves, and externally, in consultation and communication with local stakeholders).

Indeed, if a particular dysfunctional state of affairs can be seen to manifest the imbalanced dominance of each of the four resulting quadrants (

Figure 2a) then each role, if skilfully (i.e., phronetically) performed, serves to counteract and harness one of these as its respective ‘near enemy’ (

Figure 2b). For instance, a governance context in which opportunistic innovation and continuity are combined without counter-balance may well lead to runaway acceleration of technoeconomic change [

22], locking in a specific direction (hence ‘continuity’) of rapid economic growth and inequalities (hence ‘opportunistic innovation’). Yet, there is also here the opportunity for the (local government) ‘entrepreneur’ to contain and redirect these dynamics, especially when in combination with appropriate mix of the other three roles.

However, this framework also invites yet deeper understanding, up to a more profound shift in perspective. Specifically, the first step, of adding the dimension of individual action and ethics, transforms one’s relation to the question of ‘what needs to happen for local government to be up to the challenge of climate action?’ By default, we will tend to interpret this as a purely institutional question, ‘out there’, of how to ‘get local government right’ so that it can then go and ‘do climate action right’. To be sure, this approach, by shifting to ‘how’ questions, is an advance on the predominant approach of simply neglecting the capacities of current institutions of local government and presuming they are adequate, leaping straight to the question of ‘what must be done?’ (see Contribution 1, this volume). However, this approach is still, nonetheless, a manifestation of precisely the problem; and especially insofar as it simply accepts the already inimical context of austerity, inadequate capacity, etc., and overlays it with perspectives and expectations that make ‘progress’ all but impossible.

Instead, by

first reorienting to see the bridging roles as crucial, one also thereby admits the associated concern of the deliberate cultivation of a

collective ethic of personal responsibility, ethical reflection and learning as sine qua non for any progressive institutional reform [

23]. Yet, if the vertical dimension is understood in this way, the horizontal dimension is likewise reimagined. Specifically, the ‘obvious’ question above, concerning local government reform, gets recast.

No longer is it a purely institutional question. Instead, it becomes one of situated exploration of a personalized strategic practice of ever-greater conviviality, governmental competence and collective learning thereon. The individual stakeholder in local government and their ethical action thus becomes the essential window and/or vehicle for all effective governmental climate action, including the progressive improvement of the very institutions of local government.

In this way, phronesis is shown, indeed, to involve the concerted cultivation of two orthogonal, but now mutually reinforcing, issues or approaches, as against a prevailing common-sense that focuses only on one, and then in a very different form. Effective and phronetic local government climate action demands both concerted personal reflection on ends and questions of value, in and through activity together with, and in relation to, others; and concerted collective reflection on the strategic openings of oneself and others given current systems of power relations and situatedness within them. Hence, intrinsically consisting of both an ethical–individual and strategic/political–collective moment, and/or a power–knowledge and power–knowledge moment, respectively.

Such practice(s) of phronesis (i.e., of such learning, and learning about learning…), personal and collective, then themselves cultivate the activity, direction and momentum of the progressive institutional change and activity desired.I Indeed, they just

are the practising of the transformed outcome (or ‘transition’ [

24]) to which change is needed. For this activity is the cultivation of phronetic institutions and form of government [

25] that is resilient or anti-fragile [

26] precisely in being optimally capable of collective (and inseparably, personal) learning

because it is specifically and primarily oriented to that phronetic goal.

What has thus emerged, therefore, is a counter-intuitive but arresting—and, crucially, simple hence memorable—conclusion: that the cultivation of phronesis is thus the

primary goal of local government that is seeking to respond more adequately to climate emergency, even as it may seem initially as just a useful approach or means to that end. As such, reorienting to this perspective also then provides the key missing piece or new synthetic worldview [

27], that affords the integrating of disparate insights. Indeed, with the new goal of vision thus clarified, at least as initial gestalt (or even ‘flip’

Cf [

28]), these further insights can now begin to form a positive feedback spiral of activity and learning on an ongoing basis and amongst an ever-growing (and potentially fast-spreading) group of thoughtful practitioners. With the paradigm shift, in other words, such insights as occur to the disparate concrete individuals tasked with local climate action can begin to accumulate and so gather momentum as more than the sum of their parts, rather than less; avoiding a confusing mess that is simply adding to the overwhelming complexity, as is the constant risk at present.

Indeed, here we can even begin to trace the first steps towards the urgently needed reframing of a more concrete ideal enabling of such (re)constructive positive feedback loops of activity: a long-needed and -sought-for new ‘ideal’ of urban life and infrastructure. This has been missing since the disintegration of the ‘integrated ideal’ of the nineteenth to mid-twentieth century global North into the global ‘splintering urbanism’ of the late twentieth / early twenty-first century [

29], and now culminating in a ‘new urban crisis’ [

30]. The phronetic vision of today, however, is not a new ‘integrated ideal’ but rather a new ‘integrat

ing imaginary or

vision’, with the new productive process of

integrating (and infrastructur

ing to boot [

31]) coming first,

then informing the new ‘ideal’ or, rather, imaginary [

32,

33] or vision [

27].

Here again, therefore, the work of the weaver is today the necessary first step. For this reframes the equally necessary (but much more commonplace) activity of the crusader as a pragmatic idealism, and hence potentially in productive relation with the pragmatist. Conversely, absent the weaver’s influence, the crusader will tend towards strident, ideological idealism, which just polarizes and repels the pragmatist, such that they in turn may progressively become ever more cynical and intransigent in their ‘realism’, in positive feedback loops of mutual stand-off.

In short, from our starting question of ‘how can we do local government better to tackle climate emergency and unleash its potential in this regard?’, which suggests specific forms of institutional action in response, the papers here, and this reflection on them, lead to a surprising but thereby productive conclusion. The way forward on this very question actually lies elsewhere: in the decision to put phronesis and its cultivation centre-stage. This applies to both the personal action of those associated with the running of local government and politics (hence local government staff/civil servants and representatives in the first instance, but also, ultimately, all other local stakeholders too) and in the explicit operations and vision statements of the institutions of local government itself. Additionally, this requires the deliberate cultivation of balance (and rebalancing, as reintegrating) in two dimensions and

across those dimensions, namely collective strategizing and individual ethics. It is the latter, though, that has been most neglected and hence demands most attention today. Hence, perhaps most counter-intuitively, we have here emphasised the centrality for local government climate action of work on the self and self-responsibility and the associated shift in perspective or mind [

34], which can likewise only happen in and by individuals for themselves, albeit progressively over time and in active practice with others.

4. The Articles—Concrete Insights from Diverse Case Studies

Phronesis thus, we argue, presents a keyword—i.e., a compelling and fertile singular terminology and focus—for future research and practice on local government climate action. However, what do the papers of this collection have to say in this regard? We close this Introduction by turning to them, in the hope that we can situate all their diverse and insightful contributions together into a loose and productive synthesis while not aiming to claim too tight or definitive a unity of their diverse positions. Indeed, lest it need be said, we strongly encourage readers to read the articles themselves to hear the contributors in their own voice and in all their insightful detail.

It feels appropriate to start with the greater, and daunting, challenges faced by local government in the Global South. Substantial populations are vulnerable to extreme weather and disasters linked to climate change due to a lack of resilient critical infrastructure. Using data from 345 Chilean local authorities, Valdivieso, Neudorfer and Andersson [Contribution 2] examine how internal and external institutional dynamics and arrangements shape decision-making around investment in resilient critical infrastructure, a field usually examined from a technical-economic perspective.

They show that institutional dynamics moderate between capacities to act (in terms of political leadership and availability of resources) and actual outcomes (in terms of decisions to invest in new critical infrastructure). In particular, more robust internal organisational arrangements such as internal regulations, planning, coordination, and integration were associated with higher levels of investment. They observe that existing norms, conventions, routines and expectations can lead to resistance to change, and may be internally contradictory, recommending bottom-up improvements to municipal organisational robustness in terms of operational rules, communication and coordination, integration, transparency, accountability, and political support. They suggest that this can be a more significant factor in driving effective climate adaptation action than money transfers from higher-level government or other external interventions.

The key point of their article, therefore, is that organisational competence is central to successful climate action. While attending to, and investing in, institutional competences and capacities may sometimes appear like a distraction from the urgency of climate action (especially to ‘crusading’ individuals with a clear vision for a future which is markedly different to the past), Valdivieso et al. clearly show that it is central to its effective delivery. Resonating thus with the argument above, ’municipal robustness’ is, arguably, a further specification of institutional-level phronesis. Their articulation of municipal robustness foregrounds the need to strike a balance between forces pulling in different directions, e.g., flexibility vs. planning, integration vs. division of labour. This balancing of forces does not come from a universally applicable algorithm, but from the practical wisdom and skilled judgements of individuals operating within institutions that both recognise the need to strike these balances, and provide them with structures within which they can make those judgements. Again, without claiming Valdivieso et al.’s total agreement to the centrality of phronesis as presented, resonance with the arguments above regarding the importance of ‘phronetic balance’ is striking in this regard.

Peirson and Ziervogel’s article [Contribution 3] also deals with the provision of infrastructure in vulnerable communities. They focus on the ways in which informal settlements in the Global South, with basic and/or inadequate service infrastructures and informal relations with utilities companies and municipal states, adapt to the impacts of climate change, through the lens of a sanitation upgrade project in a settlement in Cape Town, South Africa. Inadequate infrastructure increases vulnerabilities to the effects of climate change, and climate change in turn exacerbates those structural vulnerabilities in positive feedback loops symptomatic of the kinds of complex system challenges and dynamics that demand a phronetic approach in response. Recognising that technical solutions often increase inequalities as they do not reach the most vulnerable communities, they examine the complex socio-institutional context in which this project developed, exploring the interactions between community groups, an NGO, and the local authority. In the case they detail, the upgrading project faltered, after a promising start, due to conflicting priorities, leading to a breakdown in relations and disagreement between different city departments and the community on how to proceed. This fuelled a longstanding resentment and mistrust of the local authority amongst the community, despite recognition of some officials engaging more openly. Here, in other words, we see collective and institutional impacts quickly morphing into personal and inter-personal issues (e.g., feelings of mistrust, disappointment, betrayal…) that then risk becoming particularly intractable, while also thereby simply exacerbating the existing challenges at the former, institutional level.

The article identifies more effective multi-level governance and inclusive horizontal coordination as particularly crucial for climate action related to informal settlements, and highlight the key enabling and constraining factors to these in this case. Peirson and Ziervogel emphasise the fragility of bottom-up, non-state action—given its still-overwhelming dependence on (inter-)personal factors, of enthusiasm, resources, connections etc.—and the need for sensitive, co-operative and transparent state support for and engagement with such action. This specifically includes the need to engage with socio-institutional factors, different socio-political realities and lived experiences, rather than assuming that multiple and diverse actors can be subsumed into a centralised, technocratic approach.

Such considerations again point to the value of a phronetic approach, of a process of ongoing learning from personal experience by concrete and diverse individuals in necessarily suboptimal situations. It particularly emphasises the importance of the often-overlooked integrating role between the forces of continuity and discontinuity, which values and can produce greater resilience in relations both within and between governance actors. It also highlights that this role is itself an ongoing process and cannot be considered as a one-off stage that can be completed and then moved beyond. In the Global South in particular, NGOs may be particularly well-placed to play these bridging roles, especially so long as they retain an explicit ‘weaver’ (and/or ‘entrepreneur’) approach and self-definition and do not veer too much into ‘crusader’ mode.

Turning to the papers from northwest Europe, over 70% of local authorities in the UK have declared a climate emergency, signalling an intention to align their policies and practices with the urgent need to tackle this emergency. However, there remains a significant gap between these high-level intentions and the actions necessary to achieve them. Yuille, Tyfield and Willis [Contribution 1] examine this gap in three UK cities—Belfast, Edinburgh and Leeds—focusing on the actual experience and understandings of local decision-makers. They identify a series of enabling and constraining factors that explain this gap, including: the shifting political priority of the climate agenda; limited understanding of how climate goals can be achieved; the interaction of national and local scales of governance; organisational culture within local authorities and their partners; the different ways in which the issue is framed; conflicts between high-level support and contentious detailed implementation; the ways in which climate action is understood as locally specific; and the risks and opportunities presented by the COVID-19 pandemic.

These factors represent a relatively uncontroversial mapping of what the challenges, opportunities, and barriers relating to rapid climate action are. Yuille et al. then move on to address how local politicians and officials engage with these factors as part of their everyday working lives. They identify distinctive patterns in working practices which different individuals may enact at different times, categorising them (as noted above) as ‘crusaders’, ‘entrepreneurs’, pragmatists’ and ‘weavers’. They emphasise the importance of ongoing learning from lived experience, at individual and institutional level, thereby continually shaping and re-shaping climate governance by focusing not just on what needs to be done, but on how local decision-makers can navigate their way through a landscape of conflicting priorities and pressures. The clear connection of these arguments to that of this Introduction has already been drawn out above.

Russell and Christie observe that the increasing interest in climate governance has tended to focus on global and national (and to a lesser extent city) scales, but that local governance is often acknowledged as a source of pioneering bottom-up action [Contribution 4]. Their article focuses on mapping and understanding micro-level climate governance in the UK, exploring the climate actions of the town and parish councils in Waverley Borough in the county of Surrey. They find that, despite a lack of national or sub-national coordination, some forms of climate action are being progressed by the County and Borough councils, as well as by some of the town and parish councils that sit below them. However, they describe these actions as improvisational and compensatory: compensating for higher levels failures and failures of coordination, and improvising due to the lack of coordination. Action is territorially highly variable, disjointed, not always evidently tied to specific local goals, and with little evidence of effectiveness. Even flows of information are horizontally and vertically limited.

In this context, Russell and Christie highlight the importance of ‘wilful actors’ who initiate activity with little or no support, guidance or leadership from higher levels of governance in driving local climate action. Like the bottom-up actions described in Cape Town, these too are fragile in the absence of improved horizontal and vertical coordination, revealing interesting analogies even across very different contexts: informal settlements in Cape Town and comparatively affluent communities in London’s ‘leafy’ commuter-belt. That similar conclusions regarding challenges and approach straddle such differences speaks to the effective—and not premature—universality of a phronetic approach.

However, our phronetic framing also suggests another form of fragility for these actions. As wilful actors are by definition pushing visions of discontinuity, enacting a ‘crusading’ role, they will often find themselves confronting pragmatist actors who value continuity, and in the absence of the bridging roles of opportunistic innovating (the entrepreneur role) or integrating (the weaver role), this confrontation can lead to stalemated paralysis. In any event, this default combination of crusaders and pragmatists alone is likely to lead to the totality of these ‘DIY’ actions adding up to less than the sum of their parts. Greater coordination, information and knowledge-sharing—more ‘weaving’ actions—are identified as crucial to re-make institutions that are capable of governance for a climate emergency.

In her article in sister journal World that is also associated with this Special Issue, von Hellermann [Contribution 5] likewise discusses the challenges of sustaining bottom-up volunteer-based local climate action as a model of local government and the limitations of the kinds of issues that tend to be addressed given this approach. The article focuses on the case of Eastbourne, a conservative town with a significant retired population on the south coast of England, and the council-citizen collaborative network model of climate governance that has emerged there since a declaration of climate emergency in 2019. She provides an auto-ethnographic account of the ups and downs, pros and cons, of such a distributed approach, dependent largely on citizen activism in collaboration with, but receiving little top-down support from, local government. Focusing on “target working groups… bringing together councillors, engaged citizens and providers” focusing on specific issues—initially trees, transport and education—the article explores the diverse constraints on effective and enduring climate governance at local level, considering both institutional and personal factors.

Regarding the former, for instance, again we find here reference to the limited budgets, time and powers of local government (in the UK), now made even harder in the context of the (post-)pandemic exigencies. Yet, it is regarding the latter, and/or its overlap and interaction with the former, that von Hellermann is most illuminating. For instance, we find that different expectations and understandings of the role and capacities of local government and/or citizen volunteers amongst different parties significantly complicates sustaining such initiatives, no matter the original optimism and energy with which they may be launched. Moreover, these disagreements appear to be most problematic where these expectations are polarized regarding the division of governmental labour between existing institutions and citizen volunteers, e.g., where staff at the former feel the limitations of their powers and so hope the latter will make happen what they cannot, while the latter may resent being asked to do—and for free—tasks that they see as ‘evidently’ the remit of council professionals. Here too, though, we find a blurred line between the emergence of disagreement on such matters and simple clash of personality, or institutional hurdles/supports and personal competence and approach, with both being crucial ‘micro-dynamics’ in the functioning, or not, of local government climate action.

The result is that the range of issues stressed by von Hellermann as crucial, and as key arenas of strategic learning, likewise range across the full spectrum, institutional to personal, strategic means to value and ends, political to ethical, highlighted by the explanation of phronesis above; and, crucially, with intimate connections and feedback loops amongst these seemingly polarized and dualistic concerns, hence demanding always holding both in mind. For instance, von Hellermann calls eloquently for a ‘both/and’ approach of bottom-up action and top-down support, and likewise personal change and institutional reform.

The importance of the latter is undeniable given that “a large part of the measures required to reduce… carbon emissions are fundamentally more about infrastructure changes that indeed need to be delivered by the authorities”. Similarly, it follows that “[t]he real power and importance of both local governments and schools ultimately lies less in (so exhausting yet so pitiful) local initiatives like ours, but in key instruments of delivery of wider, national initiatives”.

Yet the irreducible importance and centrality of the former is also illuminated here: whether in terms of the central driving force of motivated individuals, both within and outside local government, in instigating change; the challenges of their exhaustion (and with that, the initiatives they have led) and hence the crucial issue of their adequate support and remuneration; or the mediation of all these change dynamics through personal interaction amongst specific, complex, multi-dimensional people. Here, therefore, there is an implicit call for just the kind of phronetic bridging support of weavers, i.e., as key forms of institutional support focusing on the (inter-)personal dimensions of effective local government.

As she also argues, it is really only in personal experience as a citizen volunteer that one comes to a clear and living understanding of issues of strategy and power that are so pivotal regarding effective local climate action. This again illustrates the blurring of dualisms, as it is only in personal practical experience and frustration that one really learns about the seemingly external and collective issues of institutional design and organization, and how it applies ‘here’ and ‘now’ in this specific context of climate action. Indeed, von Hellermann even takes this a step further in her advocacy of an ‘engaged anthropology’ and its potential contribution to local climate action more generally, which may be read as a call precisely for the kind of qualitative strategic learning, personal and collective, that we have advocated as ‘phronesis’.

Staying in the south of England, but moving to the importance of the city-level decision-making, Drummond presents a framework to assess the state of ten factors that enable (or inhibit) effective climate governance at the city scale [Contribution 6]. He illustrates this approach through its application to the transition of passenger mobility in London, the UK’s only global mega-city and one of the most high-profile cities in the world. This framework builds on work by Van der Heijden [

35], while adding two further key governance factors, of ‘societal pressure’ and ‘conducive urban form and infrastructure’, to expand the analysis specifically for this issue of urban mobility transition. In doing so, Drummond also finds significant evidence for positivity regarding this case study, with “strong capacity for autonomy, stakeholder participation, local leadership and coordination on climate action”, resonating with the issues noted as crucial across many of the other articles. However, two issues remain causes for concern, namely: “multi-level coordination” in terms of a need for greater coordination between local and national levels of government; and intensifying funding issues, especially in the wake of the pandemic.

As such, Drummond focuses on the specifically institutional strengths and weaknesses in this case regarding local climate action. These issues speak strongly to the more substantive conclusions on this issue from a phronetic perspective, highlighting the importance of such considerations as strategically working with the, no doubt sub-optimal, affordances of the urban form as it is, or an approach balanced between effective engagement with stakeholders and competent, autonomous council leadership. Yet, even in this purely institutional register, the importance of personal, inter-personal and intra-personal (i.e., values) learning and action is still clear.

For instance, the paper notes that horizontal coordination between different constituent borough councils and/or Transport for London (TfL) is often functional only on the basis of uninstitutionalized and personal connections between two officers in the respective organizations, smoothing the process. From a purely institutional perspective, and one politically not uncommon amongst citizen-voters in the global North, relying on such fortuitous connections itself sounds like something of an institutional failure, and certainly clear evidence of a falling short regarding the kind of institutions and capacities needed to tackle these issues. Yet, a phronetic perspective would counsel greater perspective and patience in this regard, accepting that institutions will never be ‘perfect’ and hence encouraging such strategic initiative within local government insofar as it assists a muddling through and pragmatic realization of such important goals as climate action in whatever ways present themselves.

Consider likewise Drummond’s observation that many borough councils do not actually exercise powers, de jure or de facto, that they already have and so are constrained, in such cases, primarily by their own (in)actions, not by objective lack of institutional capacities. Here, again the dual personal/institutional perspective of phronesis proves illuminating. For a more self-conscious adoption of this approach by councils and their staff may encourage a more active and exploratory approach regarding not only what they can in fact already do, resonating with an ‘entrepreneur’ approach, but also then doing so in ways that bring along other stakeholders in what could be effectively a change in power/relations. Moreover, aggregated over the medium-term, such an approach also illuminates the crucial insight of Drummond, and other papers, that there are significant strategic opportunities to build up the kind of political momentum needed ultimately to demand greater clarity and redistribution from national level—i.e., precisely a constitutional resettlement—through exploiting such loopholes and openings. Such an approach, though, is again not only ultimately premised on the agency of specific individuals, but also on the specifically bridging forms of that agency, forging coalitions behind the demanded institutional changes and, with that, even subtly working towards shifting personal common-senses across society about the values that should ‘obviously’ be served by local government. The latter, thus, spells important routes to shifting the political mood, including in ways that affect national-level government and political discourse.

These twin demands, of local government ‘entrepreneurs’ and ‘weavers’—and, indeed, thence refashioned and newly complementary ‘pragmatists’ and ‘crusaders’—is likewise clear in the case study across seven local authorities in Belgium, France, the Netherlands and the UK presented by Kwon, Mlecnik and Gruis [Contribution 7]. Focusing on the issue of energy efficiency of residential housing, Kwon et al. present findings from an initiative exploring the comparative advantages of different business models for local authorities to set up ‘pop-up centres’ encouraging local citizens to upgrade their home insulation.

Here, the starting premise of this initiative is acceptance of the current distribution of powers and budgets to local authorities, aiming to work ‘from here’. Across all the localities studied, responsibilities for deep, expedited climate action weigh heavily on local government while funding and policy levers are frequently lacking. In resonance with the broader neoliberal policy orthodoxy of reducing state subsidies and encouraging fiscal self-sufficiency through enterprise, the experimental approach explored here thus aims to establish service models that are financially self-sustaining while still driving forward on local government agendas. It would be possible, therefore, to read this initiative as itself phronetic, at least in terms of a pragmatic approach working with current circumstances and accepting sub-optimal institutional arrangements as an enduring condition, not simply one that could be quickly rectified were sufficient fiscal largesse and backing from central government forthcoming.

Yet, this would be a partial interpretation of phronesis, as is illustrated by the challenges that Kwon et al. show were faced by this initiative. Most obviously, the issue of horizontal coordination (i.e., between different departments at local authorities) and stakeholder collaboration, including even active uptake of the pop-up consultancy services by citizens, are again mentioned as significant challenges and the more so the more the business model was purely in a standard private enterprise mould focused on maximized ‘returns’. In particular, while the policy entrepreneurialism in question proved reasonably effective and successful in some cases, the emphasis on this mode alone, to the exclusion of crusaders and especially weavers, left these initiatives fragile and poorly integrated with their broader normative and/or institutional context. The result is initiatives in which staff may have little longer-term strategic direction or face continual clashes of expectation and goals with others with whom they must collaborate. In short, while an initial and superficial strategic imagination is certainly a start, the hurdles thereby faced lead to a deeper engagement with phronesis and its broader set of concerns.

Finally, returning to the UK, Marsden and Anable pick up the specific issue of coordination between local and national climate policy, offering a UK-wide analysis on policy coherence in decarbonization of transport [Contribution 8]. Noting that current progress on this key high-emission sector is far too slow at present to meet even existing decarbonization targets, and the crucial role of local government in that agenda, the paper argues for the need for setting budgets and decarbonisation policies at different spatial scales, and for coherence across them, mindful of interactions across scales and territories. While the need for such coherence makes intuitive sense regardless of the issue, Marsden and Anable also emphasize its particular importance for transport emissions. Transport inevitably crosses spatial scales yet the existing policy framework in the UK places different levers at different scales. For instance, behaviour change initiatives will often be led locally (e.g., low traffic neighbourhoods, active transport schemes, congestion charging zones etc.) but are conducted within the national framework of subsidy, fuel taxes and regulation, which define the relative costs of different modes of transport.

The article presents informative analytical distinctions between different forms of local/national coherence in climate policy, specifically focusing on three key elements:

‘(carbon) budget coherence’ (viz. Are carbon budgets aligned across authorities and scales to add up to national targets? Or indeed set at all, as opposed to inconsistent net-zero target end dates that do not account for cumulative emissions?);

‘accounting coherence’ (viz. What gets counted where and at which scale (city vs. county etc.), given that journeys often start and end in different local authorities); and

‘policy coherence’ (viz. How are budgets and responsibilities aligned with the capacity and powers to act?)

Assessed against these three considerations, Marsden and Anable show that the current situation in the UK (an acknowledge leader in the field, and hence, no doubt, also elsewhere) is a messy patchwork, developed piecemeal in different territories and scales, and both top-down and bottom-up, rather than a coherent framework. The resulting lack of scalar and sectoral coordination or allocation of carbon budgets then obstructs effective action, while also enabling inaction. Indeed, absent such coherence and clarity, there remain considerable obstacles to achieving the transparency in policy goals and means needed to win public trust and to avoid inaction or blame-shifting between governments at different scales.

Crucially, though, the discussion also admits that there are no optimal solutions available, in terms of any wholesale institutional rearrangement, and especially set against the intense time pressure of climate emergency. Instead, the given complexity of policy competencies means that budgets, accounting and policy levers will necessarily be spread across scales of governance and thus need a concerted and medium-term effort to be integrated and joined up. Yet, they argue, any greater coherence in framework, for all the ensuing complexities of achieving this, would be better than the current inconsistencies & inadequacies; while translating national sectoral targets to subnational scales will likely be crucial to bring home to decision-makers the need for urgent and significant action.

Taken together, then, these two key points of the need for coherence and acceptance of the sub-optimal given arrangements, seem to be pulling in opposite directions. Yet, from a phronesis perspective, this is simply to admit the challenging but inescapable predicament of working at achievement over the medium-term of balance amongst equally important and, in fact, complementary-yet-apparently-contradictory imperatives. The alternative is precisely the polarization of positioning between a purist demand for institutional rectification first, effectively delaying climate action indefinitely, or a doomed pragmatism aiming an urgent ‘getting on with whatever can be done now’, but neglecting the profound limitations in that regard given current institutional arrangements. In short, again we find here the urgent imperative of the bridging roles highlighted by foregrounding phronesis, and thereby potentially building momentum over time that subverts the paralysis of standoff between crusaders and pragmatists into a productive mutual softening of both positions into a pragmatic radicalism (Cf Von Hellerman, Contribution 5) and an experimental pragmatism, respectively.