Abstract

This study empirically analyzes the social benefits of opening a highway by assessing the increase in housing prices in two surrounding regions: one defined as the treatment group and the other defined as the control group. Although the two regions are geographically adjacent, they belong to different administrative districts and are physically separated by natural topographical features such as mountain ranges. Both aspects make it so that the interaction or influence between the two regions is limited, which raises the probability that the control group will show a trend similar to that of the treatment group under the influence of economic factors but will not be affected by the opening of the highway. With this in mind, the benefits of accessibility improvement due to the opening of the highway are estimated by using the difference-in-differences framework, i.e., the relative change in housing prices in the treatment group compared to the control group. In addition, the corresponding highway route is analyzed by dividing it into three sections according to their opening times and locations. The findings suggest that the estimated benefits are not fictional but robust. The increase in housing prices due to the opening of a highway is estimated to be, on average, 586 to 3075 dollars per apartment (equivalently, USD 10 to 53 per square meter). These benefits are worthy of being reflected upon, complementary to a traditional cost-benefit analysis.

1. Introduction

As infrastructure, highways provide benefits such as reducing the physical costs (e.g., fuel costs) and time costs of moving between regions [1]. In addition, if a pre-existing road is more dangerous than the highway that replaces it, another potential benefit is a reduction in the number of traffic accidents. With the increasing economic scale of industries, the amount of traffic between regions seems to be ever-growing in modern society. As social overhead capital, highways reduce logistics costs in production activities, thereby improving the overall price competitiveness of the local industry. Moreover, improved accessibility between regions in terms of living conditions promotes convenience with regard to commuting for work as well as traveling for other purposes (e.g., for leisure or shopping).

Meanwhile, road construction is a typical public investment that involves huge costs, and therefore, the opportunity cost is also considered to be large. For example, it is reported that the cost of constructing a one-lane roadway in the United States ranges between $4.2 million and $15.4 million per mile, with a maintenance cost of $24,000 per year (Transportation for America [2]). Roads often create a geographically chaotic stretch of houses, shops, and jobs. Such urban sprawl limits the achievement of the roads’ intended purpose due to the induced demand for people to drive longer distances to more places. According to the analysis results of the dynamic panel model of Hymel [3], the expansion of highway traffic capacity causes a precisely matched increase in vehicular traffic. Accordingly, it was estimated that the derived vehicular traffic will cause the traffic speed to return to the pre-expansion level within approximately five years.

As such, there are conflicting arguments about the effectiveness of highway construction. In particular, while the benefits of highways in relation to production activities such as the reduction of logistics costs are clear, there is controversy about their effectiveness as a settlement-related infrastructure. Therefore, this study estimates the extent to which the opening of a highway leads to benefits in terms of accessibility improvement. Many previous studies have empirically analyzed the effects of highway opening. However, this study controls for the influence of factors other than the opening of the highway by applying a difference-in-differences analysis framework using geographic features. In other words, we empirically analyze the changes in the differences between the prices of housing in areas with improved accessibility due to a highway opening and the prices of housing in areas without it. Since there is no stylized fact about the geographic ranges that show the effects of the accessibility improvement following the opening, the proper definition of the treatment group and the control group is a key factor in minimizing the estimation error in capturing the benefits of accessibility improvement. In this study, although the areas forming these two groups are geographically adjacent, they are distinguished by the borders of administrative districts and natural topographical characteristics such as mountain ranges. Thus, mutual influence or exchanges between the two groups are restricted. As a result, the control group would have a trend in cyclical factors similar to that of the treatment group while not being affected by the opening of the highway. With this in mind, the benefits of accessibility improvement due to the opening of a highway are estimated by the relative changes in housing prices. In addition, analyses of the corresponding highway route by dividing it into three sections according to the opening time and location allow some robustness tests to be done.

The next section discusses the theoretical background and analysis model of this study. Section 3 provides an overview of the data used in the empirical analysis and the basic statistics of the included variables. Section 4 explains the results of the empirical analyses, and the policy implications are discussed in Section 5. The last section summarizes the key results of this study and suggests future tasks.

2. Theoretical Background and Empirical Analysis Model

2.1. Theoretical Background

Road construction affects productivity (Fernald [4]), trade (Duranton et al. [5], Allen and Arkolakis [6]), lane use within cities (Baum-Snow [7], Duranton and Turner [8]), and vehicle externalities (Parry et al. [9]), and it also plays an important role as a fiscal policy for economic stabilization (Leduc and Wilson [10]). However, in order to build a road, huge investments are needed, and if this decision-making is done poorly, the (local) government will face criticism for wasting its budget.

The opening of highways will affect the volume, temporal distribution, spatial distribution, and speed of vehicle traffic (Hymel [3]). This causes an increase in profits and employment by reducing the logistics cost of manufacturers, and at the same time generates the benefit of improved access to the highway for workers or residents. These benefits are often capitalized into increasing housing prices. A rise in housing prices as a benefit of accessibility improvement due to the development of transportation facilities has been reported in many studies (Armstrong and Rodríguez [11], Cheshire and Sheppard [12], Coulson and Engle [13], Franklin and Waddell [14], Henneberry [15], Iacono and Levinson [16], Martínez and Viegas [17]). On the other hand, some studies suggest that there are both positive and negative effects of highway construction that may affect housing preferences (Debrezion et al. [18], Iacono and Levinson [16], Martínez and Viegas [17], Tillema et al. [19]). The negative effects stem from the increase in traffic noise, which decreases the price of housing units located adjacent to the new highway (Kim et al. [20], Nelson [21], Theebe [22], Wilhelmsson [23]).

The economic effects of roads have been analyzed from various points of view. Shrestha [24], as well as Gonzalez-Navarro and Quintana-Domeque [25], show that the improvement in interregional connectivity due to new roads increases property value. In particular, Shrestha [24] indicates that a 1% decrease in the distance to a road raises the market price of an agricultural plot from 0.1% to 0.25%.

According to Ghani et al. [26], highways also contribute to the geographic concentration of manufacturing plants and the increase in their productivity. Similarly, Banerjee et al. [27] provide evidence that proximity to transportation networks has some positive causal effects on per capita GDP. Having roads between cities would lower the intercity transport costs and induce the income of cities to increase. Empirical results reported by Storeygard [28] suggest that a 10% decrease in transport costs leads to a 2.8% increase in a city’s economic activity.

In addition to this production side, new roads seem to encourage educational investment in developing countries. In their case study of India, Adukia et al. [29] examine the effects of 115,000 new roads on educational choices. They find that due to these roads, children stay in school longer and perform better on exams. Additionally, a study conducted by Aggarwal [30] in rural India shows that paved roads lowered the prices and increased the availability of non-local goods, i.e., greater market integration.

The impact of the highway analyzed in this study is expected to be greater, as it is directly connected to the Gyeongbu highway, which was built in 1970. This highway plays the most pivotal role in the national transportation of South Korea by connecting Seoul, the capital, and Busan, the second-largest city in the country. However, since the increase in housing prices is affected by various factors, such as changes in the economy, that are not related to the opening of the highway, it is possible to capture the net benefit of the improved accessibility resulting from the opening of the highway only when those other factors are controlled for appropriately.

2.2. Empirical Analysis Model

In order to estimate the benefits of improved access to the Gyeongbu highway, as a result of the opening of the Pyeongtaek-Jecheon highway, in terms of a rise in housing prices in the region, a hedonic model for analyzing housing price determinants is used. It is a toll highway without traffic signals. However, the effects of the highway opening are identified through a difference-in-differences framework as follows:

yjt = b0 + b1 treatj + b2 postt1 + b3 (treat*post1)jt + b4 postt2 + b5 (treat*post2)jt + Xj c + ujt

Here, yjt is the sale price (in units of ten thousand Korean won per square meter) of apartment j traded at time t. Next, treatj is whether apartment j is located in Anseong, Gyeonggi province, taking a value of 1 in the case of Anseong and 0 in the case of Jincheon or Eumseong in Chungbuk province. The variable posttk is the time point after the opening of section k. In the case of the Anseong-Namanseong (opened on 31 August 2007) section, k corresponds to 1, and in the case of the Namanseong-Daeso (opened on 11 December 2008) section, k corresponds to 2. Then, Xj is the time-invariant characteristic of apartment j, including its size, year of construction, floor, location, and the name of the complex. Finally, ujt represents a usual error term. As a method to evaluate a policy or an event (i.e., the opening of a new highway in this study), the difference-in-differences framework is one of the popular methods. However, even though the regression Equation (1) controls for the time-invariant characteristics of individual apartments between the treatment and the control group, there would still be unobserved heterogeneity. If there are enough samples in the control group, before estimating Equation (1), we can restrict the samples to those matched to the treatment group in order to lessen the possible bias coming from the dissimilar trends in prices due to the unobserved heterogeneity.

Alternatively, a traditional cost-benefit analysis could be used as an evaluation method. In Korea, the economic feasibility of public investment projects is based on cost-benefit analyses. However, this method restricts the benefits of a new highway to direct ones and excludes indirect ones. Thus, it would not be appropriate for capturing the social benefits of a new highway that may include indirect benefits.

2.3. Areas of Analysis

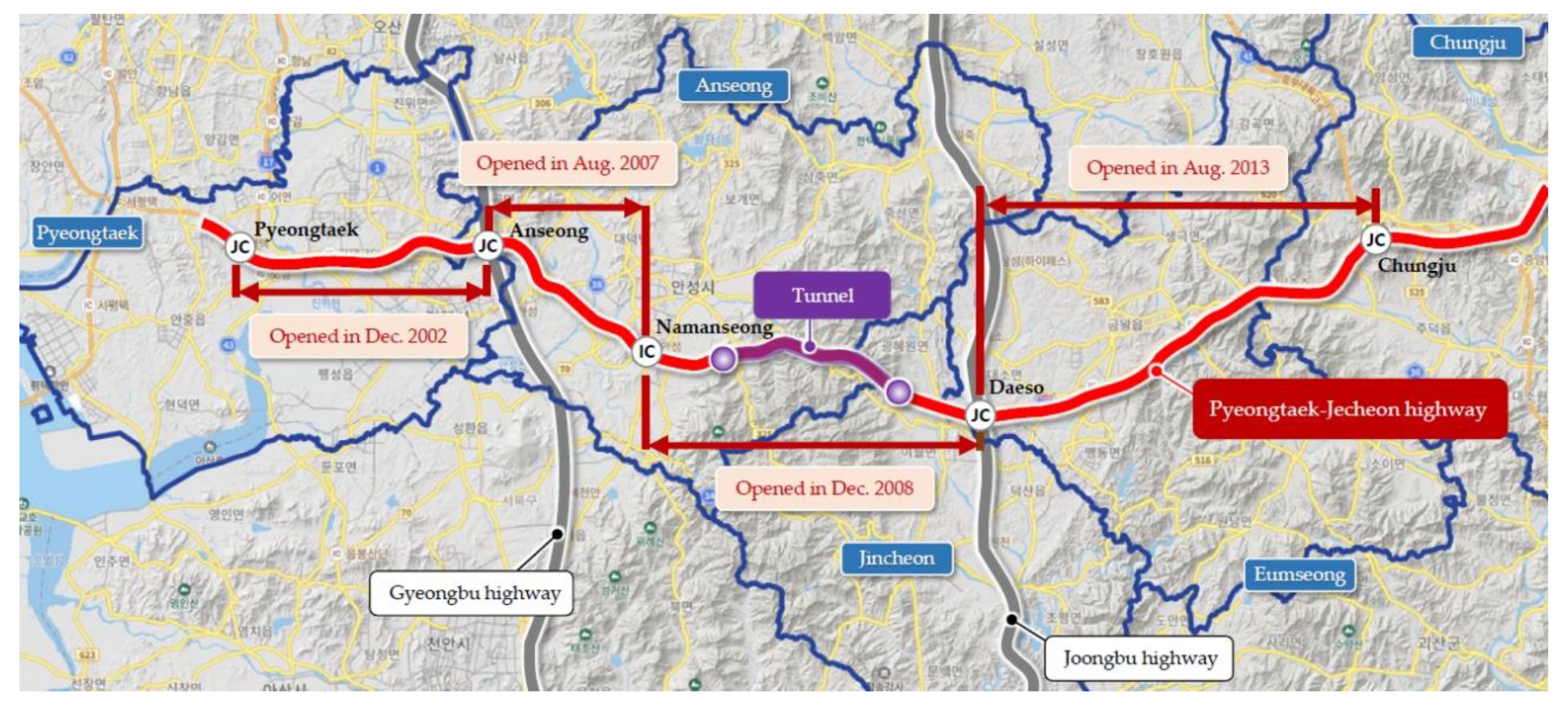

The highway of interest is the Pyeongtaek-Jecheon route, and, as parts of this route, the Anseong-Namanseong section and the Namanseong-Daeso section are analyzed (Figure 1). The route covers a total length of 109.4 km. The construction started with the opening of the Pyeongtaek-Anseong section in 2002, followed by the Anseong-Namanseong section in 2007, the Namanseong-Daeso section in 2008, the Daeso-Chungju section in 2013, and the Chungju-Jecheon section in 2015. In a geographical context, it is important to note that the Anseong-Namanseong section nearly exclusively serves the Anseong area. Moreover, although the nearby areas of Jincheon and Eumseong are geographically adjacent, before the opening of the Namanseong-Daeso section, there were difficulties regarding passage between the two regions due to the mountain range as well as the borders of administrative regions (Gyeonggi and Chungbuk province). Thus, it can be assumed that the opening of the Anseong-Namanseong section mainly affected only the residents of Anseong. Levkovich et al. (2016) pointed out the inadequate definition of the treatment group and the control group as one of the reasons for studies finding different results regarding the effects of a highway opening on the housing market. To address this issue, this study assumes that the treatment group and the control group experience similar cyclical changes in housing prices because they are geographically adjacent, while the effects of the highway opening are limited to the treatment group because they are separated physically and socially due to natural topography and administrative boundaries.

Figure 1.

Pyeongtaek-Jecheon Highway Route Map.

In the regression Equation (1), the effects of an increase in neighboring housing prices due to the opening of the Anseong-Namanseong section are estimated and represented by parameter b3. The benefits of improved accessibility to the Gyeongbu highway due to the opening of this section would be provided to residents in Anseong, and thus, b3 is supposed to have a positive value. On the other hand, since the treatment group was defined as housing located in Anseong, the opening of the Namanseong-Daeso section would cause an increase in the price of housing located in Jincheon or Eumseong, which form the control group. Thus, parameter b5 would have a negative value. However, since the Joongbu highway opened in 1987, Jincheon and Eumseong already experienced improved accessibility, and their residents may not experience substantial extra benefits from the opening of the Namanseong-Daeso section in 2007. As such, the estimate is likely to be statistically insignificant or close to zero.

3. Data and Variables

3.1. Data

In this study, the actual transaction price data, obtained through the real transaction price disclosure system of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (http://rtdown.molit.go.kr/ (accessed on 1 March 2022)), are used for analysis. The transactions recorded in this system are for land, housing (apartment, multiplex housing/townhouse, single/multi-family housing), so-called “officetels” (i.e., a type of studio apartment in a multi-purpose building with residential and commercial units), commercial real estate reported to the local government, and the resale of apartment sales/occupancy rights. In the case of apartments, the disclosure of data includes the address, the name of the complex (the name of the building in the case of a townhouse/multiplex housing), the size of the apartment, the contract date, the transaction amount, the floor, and the year of construction.

The Pyeongtaek-Jecheon highway, the subject of analysis, consists of five sections (Table 1), including the Anseong-Namanseong section opened in 2007 and the Namanseong-Daeso section opened in 2008. Since the current study focuses on the effects of opening these two particular sections, the used dataset concerns all apartments traded in the period from 1 January 2006 to 31 December 2009. However, unlike transactions in general industrial products, real estate transactions are highly unlikely to respond immediately to any event, so transactions around the time of opening—i.e., from two months prior to the opening date to two months after the opening date—are excluded from the analysis. In other words, in the case of the Anseong-Namanseong section opened on 31 August 2007, apartment sales transactions made between 30 June 2007 and 31 October 2007 are not included in the analysis. In total, 18,187 apartment sales transactions were included in the regression analysis for the entire period.

Table 1.

Opening times for each section of the Pyeongtaek-Jecheon route.

3.2. Variables

Table 2 shows the basic statistics of the variables. Regarding the characteristics of the apartments included in the regression analysis, the apartment sizes range from 25.68 square meters to 164.12 square meters, and the average corresponds to 58.57 square meters. The floors on which the apartments are located vary from the (lowest) 1st floor to the (highest) 25th floor, with the average being the 8th floor. The average number of years since construction is 7.49 years. The proportion of apartment sales transactions belonging to the treatment group, which is defined as the area experiencing an impact on housing prices due to the opening of the highway, is 60%. By time point, 42% of the transactions took place before the opening of the Anseong-Namanseong section, 58% took place after its opening, and 17% of the transactions took place after the opening of the Naman-Namanseong section. The average apartment transaction price rose annually from 1.058 million won per square meter in 2006 to 1.376 million won in 2009, representing an average annual growth rate of 9.2%. Considering that the consumer price index rose at an average annual rate of 3.3% during the same period, this implies that the increase in apartment sale prices in the analyzed area exceeded the rate of inflation.

Table 2.

Basic Statistics of Variables.

4. Empirical Results and Discussions

4.1. Baseline

Table 3 presents the empirical analysis results regarding the effects of the opening of the Anseong-Namanseong section and the Namanseong-Daeso section of the Pyeongtaek-Jecheon highway on improved accessibility, as captured in terms of the capitalization into housing prices in the region. Column (1) includes the number of years since the construction of individual apartment complexes and their squares as control variables, while Column (2) includes dummy variables for individual apartment complexes.

Table 3.

Results of estimating the effects of the opening of the Pyeongtaek-Jecheon highway on housing prices.

Prior to assessing the effects of opening the highway, it is necessary to examine the difference in apartment prices according to the characteristics of the apartments in order to examine the universal validity of the analysis results. It can be seen that the larger the size of the apartment and the higher the floor it is located on, the higher the apartment price per unit area is, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies. According to the results in Column (1), it can be seen that as more time elapsed after construction, the housing price decreased, albeit at a gradually diminishing rate. In general, it is assumed that apartment prices reach their lowest level after about 26 years, which roughly corresponds to the 30-year life cycle commonly set for apartment reconstruction.

With the opening of the Anseong-Namanseong section, the prices of apartments in Anseong, which is adjacent to Jincheon and Eumseong, Chungbuk province, have increased statistically significantly by about 63,000 won per square meter in Column (1) and 12,000 won per square meter in Column (2). These numbers reflect the effects of the improved accessibility to the Gyeongbu highway for people living in Anseong due to the opening of the Anseong-Namanseong section of the Pyeongtaek-Jecheon highway. Given the average apartment size of 58.57 square meters (Table 2), this benefit corresponds to an average of $586 to $3075 per apartment.

On the other hand, although the opening of the Namanseong-Daeso section improves access to the Gyeongbu highway through the Pyeongtaek-Jecheon highway for residents in Jincheon and Eumseong in Chungbuk province, this increase in transportation convenience appears not to be capitalized into a relative increase in apartment prices in the region. This is because the Joongbu highway, which opened in 1987, already offered Jincheon and Eumseong improved accessibility.

4.2. Robustness

Table 4 shows the analysis results when dividing the entire analysis period in Table 3 into two shorter periods that are centered on the opening times of the two sections. The first column shows the results when the analysis is limited to the period from 1 January 2006 to 11 December 2008, which is the period ending before the opening of the Namanseong-Daeso section. In other words, it shows the impact of the opening of the Anseong-Namanseong section on 31 August 2007, irrespective of the opening of the Namanseong-Daeso section. The results reveal that, with the opening of the Anseong-Namanseong section, the prices of apartments in nearby Anseong increased statistically significantly compared to the prices of apartments in Jincheon and Eumseong, which form the control group. However, this relative increase was 46,000 won per square meter, which is somewhat smaller than the 63,000 won presented in Column (1) of Table 3.

Table 4.

Results when the analysis period is divided to estimate the impact per section.

The second column presents the results when the analysis is limited to the period from 1 September 2007 to 31 December 2009, which is the period starting after the opening of the Anseong-Namanseong section. This aims to exclude the effects of the opening of the Anseong-Namanseong section and to exclusively analyze the changes in the prices of neighboring apartments due to the opening of the Namanseong-Daeso section on 11 December 2008. The estimate (0.9453) for the coefficient of the variable representing the effect of the opening of the corresponding section is not statistically significant at all, and it is similar to the result (0.6620) presented in Column (1) of Table 3.

Table 5 corresponds to a kind of placebo test result to show that the analysis result presented in Table 3 is not a spurious result due to simple economic fluctuations. In this test, only housing transactions made in 2006, when the highway sections were not opened yet, are included in the analysis. A dummy variable representing transactions made in the second half of 2006 is created arbitrarily, and it is tested whether or not the relative increase in housing prices in Anseong after the opening of the Anseong-Namanseong section shown in Table 3 is a simple trend through the interaction term between this dummy variable and a dummy variable indicating the housing in Anseong. The results in Table 5 confirm that there were no asymmetric economic fluctuations that caused relatively faster growth in housing prices in Anseong than in Jincheon and Eumseong.

Table 5.

Results for the possibility of different economic trends between groups.

5. Discussion

Highways have several positive effects. Fernald [4] suggested, through empirical analysis, that the construction of highways connecting US states before 1973 contributed to the improvement of productivity in vehicle-intensive industries. However, this increase in productivity is not continuous and appears to be limited to one time. Duranton and Turner [8] empirically analyzed the growth of US cities near highways connecting US states. According to them, if a city’s initial inventory of highways increases by 10%, employment in the city increases by 1.5% over the next 20 years. On the other hand, according to Allen and Arkolakis [6], trade costs are different due to differences in geographic location, which affect productivity and cause income inequality between regions. They suggested that the construction of a highway increases welfare by 1.1 to 1.4%, which is sufficiently greater than the cost of constructing the highway. Duranton et al. [5] analyzed the effects of highways on transactions between large cities in the United States. Their results showed that a 10% increase in highways in a city increases the city’s exports by 5%, as it allows the city to specialize in industries that use highways more intensively.

In contrast, a study by Asher and Novosad [31] found that although India’s rural national road construction program caused some workers to shift from agriculture to other industries, it did not cause significant changes in agricultural performance, income, or assets. Noticeably, it was pointed out that the effects are not large enough to slightly increase employment in village firms. One of the many purposes of highway construction is to alleviate traffic congestion in the city. However, as seen in the results of Hymel [3], this effect of road construction appears only for a short period of time. According to the Fundamental Law of Road Congestion (Downs [32]), an increase in roads does not alleviate traffic congestion in the long run because it derives demand for road use on a similar scale. In addition, as seen in the results of Baum-Snow [7], the construction of highways moves the population from the inner city to the suburbs. This causes urban proliferation and wasteful traffic.

Levkovich et al. [33] suggested that the construction of highways improves access and increases housing prices, while noise pollution and the concentration of traffic from highways decrease housing prices. Although these conflicting effects exist, the overall effects of highways on housing prices are generally analyzed to be positive. The negative impacts of traffic noise from highways are often considered to cause a drop in nearby housing prices. For example, Theebe [22]’s empirical analysis showed that, on average, a price drop of 5% occurs.

Overall, it is not easy to draw definite conclusions about the effects of opening a highway. Different results may appear when the evaluation of effectiveness is focused on production activities, such as changes in productivity or employment, improving accessibility or sedentary activities, or taking into account negative aspects such as traffic noise or congestion. Nevertheless, the decision to construct a highway, which requires a huge budget, should be based on the results of a cost-benefit analysis from the perspective of society as a whole. However, the absolute and relative weight of the benefits may vary depending on what the main purpose of the highway is, and benefits from a specific point of view may be emphasized.

From the local government’s point of view, the potential impact of a new highway on the population would be regarded as important. Depending on who migrates to the local area, the economic effects would vary. The improved transportation networks due to a new highway would encourage firms to (re)locate near the area. Then, workers would also be attracted to the area. In the larger labor pool, agglomeration economies would be realized, and labor productivity and wages would rise. Then, the overall quality of life in the area would increase.

The method used in this study is worthy of being applied to developing countries or rural areas. In the case of developed countries or urbanized areas, transportation networks would already be well-established; therefore, as Fernald [4] argued, new highways would not lead to remarkable benefits.

6. Conclusions

The opening of highways induces positive effects on production activities and settlement conditions. However, it appears that there is a limit to the alleviation of traffic congestion due to the huge number of resources being invested in the construction and the derived demand for road traffic. In other words, the opportunity cost of highway construction and the possibility of limited effects should be considered. In the end, the benefits of a highway opening should be estimated as accurately as possible, and such insights should form the basis on which the decision to construct a highway is made.

This study empirically analyzes the benefits of opening a highway by applying a difference-in-differences analysis framework to assess the capitalization of these benefits into an increase in neighboring housing prices. More specifically, the study examines two adjacent regions that are physically separated by a mountain range and independent of mutual economic activities. In this way, the effects of simple economic fluctuation factors unrelated to the effects of opening the highway are eliminated. According to the empirical analysis results, the improved accessibility due to a highway opening causes a relative increase in neighboring housing prices, which shows that the benefits of improved settlement conditions are capitalized into housing prices. On the other hand, the analysis reveals that the actual benefits of opening additional routes in areas where access to highways already exists are relatively small. The study results suggest robustness through two complementary analyses in which the benefits are assessed per highway section.

The difference-in-differences analysis framework applied in this study has been used in some earlier studies. In order for this analysis framework to be appropriate as a methodology in the present study, two basic requirements need to be met. First, the benefits of opening a highway should, at least theoretically, appear only in the treatment group and not in the control group. It is assumed that this requirement has been met sufficiently by selecting two regions that are physically separated by a mountain range. Second, assuming there was no highway opening, the treatment group and the control group should show the same trend in time-series changes. This requirement is expected to have been met by having the control group region geographically adjacent to the treatment group region. Nonetheless, the reported study is limited because the analysis period is relatively short, only allowing the estimation of benefits over four years. Highways belonging to infrastructure will, however, cause long-term impacts. Although data on housing prices after 2009 are available, it is not easy to control for other external factors that occur during the period, so follow-up analysis is scheduled as a future task.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.K. and S.H.H.; methodology, W.K. and S.H.H.; software, S.H.H.; validation, W.K. and S.H.H.; resources, W.K.; data curation, W.K.; writing—original draft preparation, W.K. and S.H.H.; writing—review and editing, W.K. and S.H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The corresponding author received financial support from the Korean Expressway Corporation for this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on previous versions of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Errampalli, M.; Senathipathi, V.; Thamban, D. Effect of congestion on fuel cost and travel time cost on multi-lane highways in india. Int. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2015, 5, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transportation for America. The Congestion Con: It’s All a Lie. 2022. Available online: https://t4america.org/maps-tools/congestion-con/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Hymel, K. If you build it, they will drive: Measuring induced demand for vehicle travel in urban areas. Transp. Policy 2019, 76, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernald, J.G. Roads to Prosperity? Assessing the Link Between Public Capital and Productivity. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duranton, G.; Morrow, P.M.; Turner, M.A. Roads and Trade: Evidence from the US. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2013, 81, 681–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.; Arkolakis, C. Trade and the Topography of the Spatial Economy *. Q. J. Econ. 2014, 129, 1085–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baum-Snow, N. Did highways cause suburbanization. Q. J. Econ. 2007, 122, 775–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duranton, G.; Turner, M. Urban growth and transportation. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2012, 79, 1407–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, I.; Walls, M.; Harrington, W. Automobile Externalities and Policies. J. Econ. Lit. 2007, 45, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leduc, S.; Wilson, D. Fueling Road Spending with Federal Stimulus. FRBSF Econ. Lett. 2014, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, R.J.; Rodríguez, D.A. An Evaluation of the Accessibility Benefits of Commuter Rail in Eastern Massachusetts using Spatial Hedonic Price Functions. Transportation 2006, 33, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, P.; Sheppard, S. On the Price of Land and the Value of Amenities. Economica 1995, 62, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, N.; Engle, R.F. Transportation costs and the rent gradient. J. Urban Econ. 1987, 21, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J.; Waddell, P. A hedonic regression of home prices in King County, Washington, using activity-specific accessibility measures. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board 82nd Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Henneberry, J. Transport investment and house prices. J. Prop. Valuat. Invest. 1998, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacono, M.; Levinson, D. Location, regional accessibility, and price effects: Evidence from home sales in Hennepin County, Minnesota. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2011, 2245, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez, L.; Viegas, J. Effects of transportation accessibility on residential property values. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2009, 2115, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrezion, G.; Pels, E.; Rietveld, P. The Impact of Railway Stations on Residential and Commercial Property Value: A Meta-analysis. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2007, 35, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tillema, T.; Hamersma, M.; Sussman, J.; Arts, J. Extending the scope of highway planning: Accessibility, negative externalities and the residential context. Transp. Rev. 2012, 32, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Park, S.; Kweon, Y. Highway traffic noise effects on land price in an urban area. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2007, 12, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J. Highway noise and property values: A survey of recent evidence. J. Transp. Econ. Policy 1982, 16, 117–138. [Google Scholar]

- Theebe, M.A.J. Planes, Trains, and Automobiles: The Impact of Traffic Noise on House Prices. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2004, 28, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsson, M. The Impact of Traffic Noise on the Values of Single-family Houses. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2000, 43, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.A. Roads, Participation in Markets, and Benefits to Agricultural Households: Evidence from the Topography-Based Highway Network in Nepal. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2020, 68, 839–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gonzalez-Navarro, M.; Quintana-Domeque, C. Paving Streets for the Poor: Experimental Analysis of Infrastruc-ture Effects. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2016, 98, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghani, E.; Goswami, A.; Kerr, W. Highway to Success: The Impact of the Golden Quadrilateral Project for the Location and Performance of Indian Manufacturing. Econ. J. 2016, 126, 317–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Duflo, E.; Qian, N. On the road: Access to transportation infrastructure and economic growth in China. J. Develop. Econ. 2020, 145, 102442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Storeygard, A. Farther on down the Road: Transport Costs, Trade and Urban Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2016, 83, 1263–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adukia, A.; Asher, S.; Novosad, P. Educational Investment Responses to Economic Opportunity: Evidence from Indian Road Construction. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2020, 12, 348–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aggarwal, S. Do rural roads create pathways out of poverty? Evidence from India. J. Dev. Econ. 2018, 133, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, S.; Novosad, P. Rural Roads and Local Economic Development. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 797–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Downs, A. The law of peak-hour expressway congestion. Traffic Q. 1962, 16, 393–409. [Google Scholar]

- Levkovich, O.; Rouwendal, J.; Van Marwijk, R. The effects of highway development on housing prices. Transportation 2016, 43, 379–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).