The Importance of Sustainability Aspects When Purchasing Online: Comparing Generation X and Generation Z

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainability across Generations

| Author(s) (Year) | Method | Generational Focus | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulut et al. (2017); [44] | Mann-Whitney U Tests | Baby Boomers, Gen X, Y, and Z | Unneeded consumption differs across groups: Baby Boomers have the highest level of unneeded consumption, Gen Zers the fewest. |

| Dabija (2018); [45] | SEM | Baby Boomers, Gen X, Z, Millennials | Gen Zers and Millennials were found to have the strongest loyalty towards green-oriented apparel retail stores. |

| Dabija and Băbuț (2019); [6] | SEM | Gen X, Millennials | Retailer’s sustainable behavior has an influence on Millennials’ apparel store patronage and no influence on Xers. |

| Dabija and Bejan (2018); [18] | SEM | Baby Boomers, Gen X, Z, Millennials | Baby Boomers choose those green DIY stores whose market strategy is in line with their personal sacrifices to protect the environment. Xers choose green DIY stores to protect the environment for future generations. Millennials choose DIY stores whose strategies are in line with their own aspirations for environmental protection. Zers choose green DIY stores depending on the financial sacrifice they have to make. |

| Johnstone and Lindh (2018); [42] | Focus groups, interviews, SEM | Mainly millennials | The older consumers are, the more they are aware of sustainability issues. As sustainability is perceived as more complex for millennials, influencers are important to them to create sustainability awareness. |

| Kapferer and Michaut-Denizeau (2020); [46] | Correlations; Descriptive statistics; regression | Gen X, Millennials | Luxury and sustainability are perceived as contradictory across millennials from multiple countries. Millennials should be split into sub-segments. |

| Lakatos et al. (2018); [43] | ANOVA | Gen X, Y, Z | Gen Xers are the most concerned about the environment but Gen Yers are more open towards reducing resource consumption. |

| Littrell et al. (2005); [8] | ANOVA, Multiple Regression | Baby Boomers, Gen X, Swing | All generation cohorts put emphasis on fair trade philosophy (wages, working conditions, and environment). |

| Pencarelli et al. (2020); [4] | SEM | Gen Y, Z | Gen Yers were found to exhibit more sustainable habits than Gen Zers. |

| Severo et al. (2017); [27] | Multiple linear regression, ANOVA | Baby Boomers, Gen X, Y | Baby Boomers presented greater environmental sustainability awareness in relation to sustainable consumption behavior. |

| Severo et al. (2018); [28] | SEM | Baby Boomers, Gen X, Y | Gen Yers perceive organizations’ cleaner production, social responsibility, and eco-innovations as less intense. |

| Sogari et al. (2017); [47] | Logistic regression | Millennials, Non-Millennials | The young generation is more sensitive towards energy issues and less towards possession of environmental certification. |

2.2. Measuring the Purchase of Sustainable Products Implicitly

2.3. Comparing CBC with ACBC Experiments

2.4. Hypothetical Framework

3. Method

3.1. Pre-Study

3.2. Main Study

3.2.1. Survey

3.2.2. Sampling

4. Results

4.1. Within-Generation Analysis

4.1.1. Generation X

4.1.2. Hierarchical Bayes Estimation

4.1.3. (Welch-)ANOVA

4.1.4. Clustering Analysis

4.1.5. Generation Z

4.1.6. (Welch-)ANOVA

4.1.7. Clustering Analysis

4.2. Between-Generation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

5.3. Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Generation Z (n = 305) | Generation X (n = 305) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Proportion (in %) | Frequency | Proportion (in %) | ||

| Gender | Female | 187 | 61.3 | 154 | 50.5 |

| Male | 117 | 38.4 | 151 | 49.5 | |

| Diverse | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Age | 16–20 years | 133 | 43.6 | 0 | 0 |

| 20–25 years | 172 | 56.4 | 0 | 0 | |

| 44–48 years | 0 | 0 | 56 | 18.4 | |

| 49–53 years | 0 | 0 | 104 | 34.1 | |

| 54–59 years | 0 | 0 | 145 | 47.5 | |

| Education | Without qualification | 7 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Primary education | 10 | 3.3 | 12 | 3.9 | |

| Secondary School level I | 81 | 2.,6 | 48 | 15.7 | |

| High School degree | 143 | 46.9 | 38 | 12.5 | |

| Technical education | 35 | 11.5 | 139 | 45.6 | |

| Bachelor | 26 | 8.5 | 22 | 7.2 | |

| Master | 1 | 0.3 | 41 | 13.4 | |

| PhD | 1 | 0.3 | 5 | 1.6 | |

| other | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Net Income (€) | ≤499 | 61 | 20.0 | 14 | 4.6 |

| 500–999 | 45 | 14.8 | 29 | 9.5 | |

| 1.000–1.499 | 59 | 19.3 | 43 | 14.1 | |

| 1.500–1.999 | 30 | 9.8 | 42 | 13.8 | |

| 2.000–2.499 | 35 | 11.5 | 49 | 16.1 | |

| 2.500–2.999 | 10 | 3.3 | 40 | 13.1 | |

| ≥3.000 | 13 | 4.3 | 68 | 22.3 | |

| no specification | 52 | 17.0 | 20 | 6.6 | |

| Online shopping experience | Yes, very frequently | 256 | 83.9 | 246 | 80.7 |

| Yes, occasionally | 49 | 16.1 | 59 | 19.3 | |

| None | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Appendix C

| Attribute Levels | Average Zero- Centered Utilities | Standard Deviation |

| Regular fit, black | 30.03 | 56.58 |

| Slim fit, black | −19.98 | 52.14 |

| Regular fit, colored | 20.32 | 59.38 |

| Slim fit, colored | −30.37 | 43.31 |

| Waterproof, windproof, breathable (wwb) | 4.02 | 20.39 |

| wwb, minimized package size | −10.33 | 14.21 |

| wwb, minimized package size, low weight | 6.30 | 17.25 |

| Synthetical materials | −25.85 | 42.39 |

| Recycled materials | 11.77 | 26.29 |

| Bio-based materials | 14.08 | 26.91 |

| No eco-labels | −22.76 | 30.76 |

| Bluesign | −6.90 | 20.91 |

| OEKO-TEX | 29.65 | 24.52 |

| No social label | −20.92 | 32.05 |

| FWF | 1.00 | 19.82 |

| Fair Trade | 19.92 | 21.24 |

| Made in Asia | −66.41 | 35.67 |

| Made in Europe | 24.56 | 20.82 |

| Made in Germany | 41.85 | 32.12 |

| 79.00 EUR | 92.10 | 64.75 |

| 119.00 EUR | 31.45 | 26.48 |

| 159.00 EUR | −27.27 | 28.65 |

| 199.00 EUR | −96.28 | 58.36 |

| None-Option | 131.52 | 105.79 |

| Levels | Average Importances (in %) | Standard Deviation |

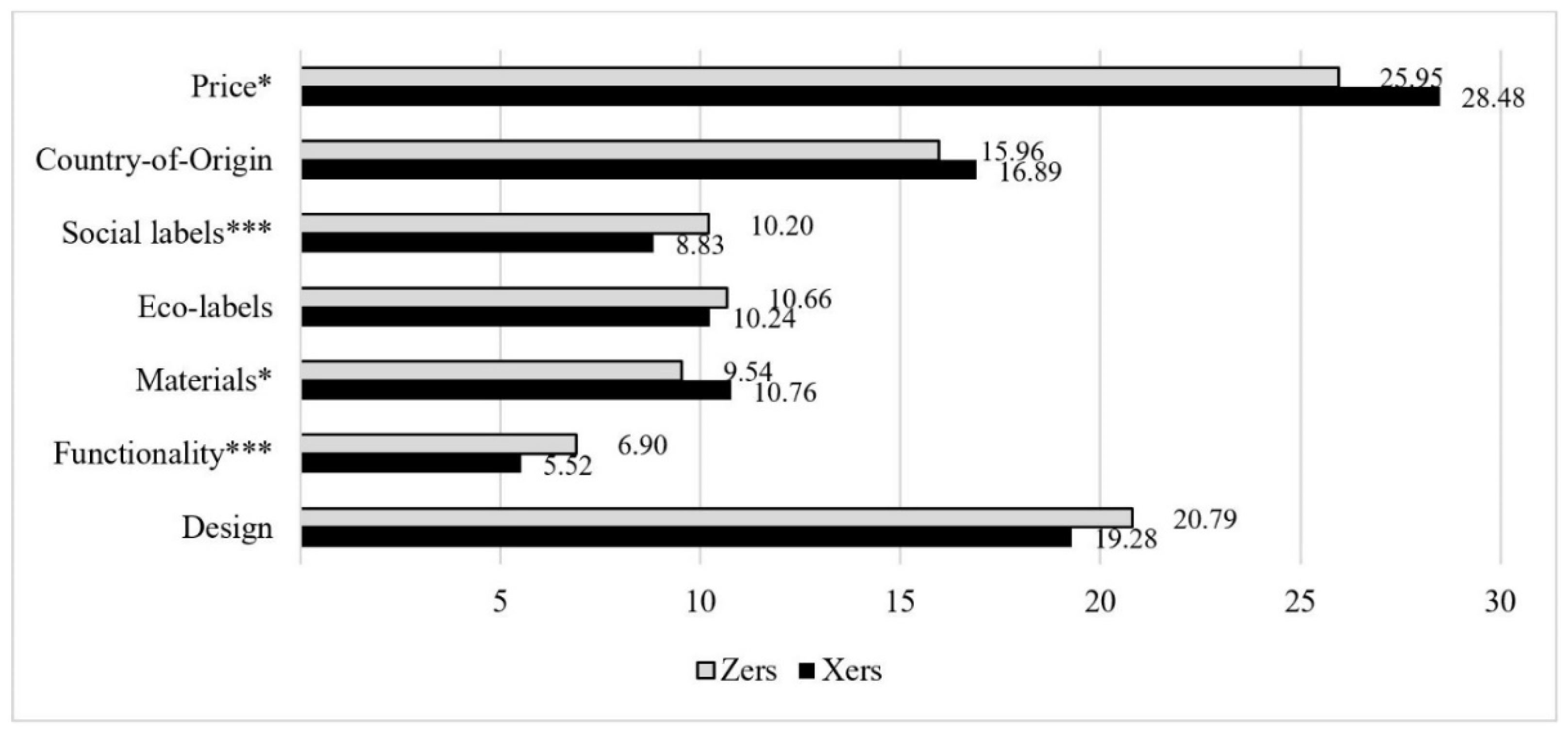

| Design | 19.28 | 9.45 |

| Functionality | 5.52 | 3.06 |

| Materials (major proportion) | 10.76 | 6.27 |

| Eco-labels | 10.24 | 4.77 |

| Social labels | 8.83 | 4.73 |

| Country-of-origin | 16.89 | 8.21 |

| Price | 28.48 | 14.83 |

Appendix D

| Average Silhouette Width Total | Average Silhouette Width | Separation | Dunn Index | Entropy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | BIC | 2loglikelihood | Cluster 1 (n = 163) | Cluster 2 (n = 142) | 2.39 | 0.04 | 0.69 | |

| 84,910.54 | 84,962.63 | −84,882.54 | 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.24 | |||

| Average Silhouette Width Total | Average Silhouette Width | Separation | Dunn Index | Entropy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | BIC | 2loglikelihood | Cluster 1 (n = 135) | Cluster 2 (n = 170) | 6.18 | 0.10 | 0.69 | |

| 88,546.32 | 88,598.40 | −88,518.32 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.26 | |||

Appendix E

| Attribute Levels | Average Zero- Centered Utilities | Standard Deviation |

| Regular fit, black | 46.69 | 58.96 |

| Slim fit, black | 32.47 | 48.63 |

| Regular fit, colored | −31.40 | 41.03 |

| Slim fit, colored | −47.76 | 49.93 |

| Waterproof, windproof, breathable (wwb) | 1.80 | 25.02 |

| wwb, minimized package size | −8.34 | 17.21 |

| wwb, minimized package size, low weight | 6.55 | 23.68 |

| Synthetical materials | −15.23 | 36.33 |

| Recycled materials | 15.97 | 28.30 |

| Bio-based materials | −0.74 | 25.27 |

| No eco-labels | −31.55 | 31.97 |

| Bluesign | 12.02 | 25.56 |

| OEKO-TEX | 19.52 | 24.94 |

| No social label | −31.07 | 31.54 |

| FWF | 8.10 | 23.68 |

| Fair Trade | 22.96 | 21.64 |

| Made in Asia | −58.55 | 38.92 |

| Made in Europe | 30.10 | 26.64 |

| Made in Germany | 28.44 | 34.79 |

| 79.00 EUR | 79.64 | 66.11 |

| 119.00 EUR | 28.84 | 29.85 |

| 159.00 EUR | −24.24 | 27.67 |

| 199.00 EUR | −84.24 | 62.15 |

| None-Option | 99.46 | 68.54 |

| Average Importances | Average Importances (in %) | Standard Deviation |

| Design | 20.79 | 10.49 |

| Functionality | 6.90 | 3.47 |

| Materials (major proportion) | 9.54 | 5.53 |

| Eco-labels | 10.66 | 5.49 |

| Social labels | 10.20 | 5.23 |

| Country-of-origin | 15.96 | 7.72 |

| Price | 25.95 | 14.69 |

Appendix F

References

- Ratten, V. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and sport entrepreneurship. IJEBR 2020, 26, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, L.; Komárková, L.; Egerová, D.; Mičík, M. The effect of COVID-19 on consumer shopping behaviour: Generational cohort perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissitsa, S.; Kol, O. Generation X vs. Generation Y–A decade of online shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencarelli, T.; Ali Taha, V.; Škerháková, V.; Valentiny, T.; Fedorko, R. Luxury Products and Sustainability Issues from the Perspective of Young Italian Consumers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T.; Kaneko, S. Is the younger generation a driving force toward achieving the sustainable development goals? Survey experiments. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 125932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.-C.; Băbuț, R. Enhancing Apparel Store Patronage through Retailers’ Attributes and Sustainability. A Generational Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, H.; Hoffmann, S. Transparent Price Labelling for Sustainable Products: A Boost for Consumers’ Willingness to Buy? MAR 2019, 41, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littrell, M.A.; Jin Ma, Y.; Halepete, J. Generation X, Baby Boomers, and Swing: Marketing fair trade apparel. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2005, 9, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oláh, J.; Kitukutha, N.; Haddad, H.; Pakurár, M.; Máté, D.; Popp, J. Achieving Sustainable E-Commerce in Environmental, Social and Economic Dimensions by Taking Possible Trade-Offs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, T.; Bişkin, F.; Kılınç, N. Sustainable dressing: Consumers’ value perceptions towards slow fashion. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 1548–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilcher, J. Mannheim’s sociology of generations: An undervalued legacy. Br. J. Sociol. 1994, 45, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schewe, C.D.; Meredith, G. Segmenting global markets by generational cohorts: Determining motivations by age. J. Consum. Behav. 2004, 4, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, K. Das problem der generationen. Kölner Vierteljahrsh. Soziolo. 1927, 69, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Mannheim, K. The problem of generations. Essays Sociol. Knowl. 1952, 57, 276–322. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, K.; Petersen, L.; Hörisch, J.; Battenfeld, D. Green thinking but thoughtless buying? An empirical extension of the value-attitude-behaviour hierarchy in sustainable clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Use of The Internet for Trip Planning: A Generational Analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.-C.; Bejan, B.M. Green DIY store choice among socially responsible consumer generations. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2018, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cruz, F.-J.; Fernández-Díaz, M.-J. Generation Z’s teachers and their digital skills. Comun. Rev. Científica. Comun. Y Educ. 2016, 24, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R.; Gonthier, J.; Lajante, M. Generation Y and online fashion shopping: Orientations and profiles. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 48, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Bock, D.; Joseph, M. Green marketing: What the Millennials buy. J. Bus. Strategy 2013, 34, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassiouni, D.H.; Hackley, C. ‘Generation Z’ children’s adaptation to digital consumer culture: A critical literature review. J. Cust. Behav. 2014, 13, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtner, S.; Soyez, K. How to catch the generation Y: Identifying consumers of ecological innovations among youngsters. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 106, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. Understanding the Millennials’ Integrated Ethical Decision-Making Process: Assessing the Relationship between Personal Values and Cognitive Moral Reasoning. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 1671–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, L.; Contini, C.; Romano, C.; Scozzafava, G. Changes in dietary preferences: New challenges for sustainability and innovation. J. Chain. Netw. Sci. 2015, 15, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, E.A.; de Guimarães, J.C.F.; Brito, L.M.P.; Dellarmelin, M.L. Environmental sustainability and sustainable consumption: The perception of baby boomers, generation X and Y in Brazil. Rev. Gestão Soc. E Ambient.-RGSA 2017, 11, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, E.A.; de Guimarães, J.C.F.; Dorion, E.C.H. Cleaner production, social responsibility and eco-innovation: Generations’ perception for a sustainable future. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, D.; Touzani, M.; Ben Slimane, K. Marketing to the (new) generations: Summary and perspectives. J. Strateg. Mark. 2017, 25, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.-C.; Bejan, B.M.; Pușcaș, C. A Qualitative Approach to the Sustainable Orientation of Generation Z in Retail: The Case of Romania. JRFM 2020, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, P.; Saunders, C.; Dalziel, P.; Rutherford, P.; Driver, T.; Guenther, M. Comparing generational preferences for individual components of sustainability schemes in the Californian wine market. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2020, 27, 1091–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.-H.J.; Tsai, C.-H.K.; Chen, M.-H.; Lv, W.Q. US sustainable food market generation Z consumer segments. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenidou, I.C.; Mamalis, S.A.; Pavlidis, S.; Bara, E.-Z.G. Segmenting the generation Z cohort university students based on sustainable food consumption behavior: A preliminary study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigerna, S.; Micheli, S.; Polinori, P. New generation acceptability towards durability and repairability of products: Circular economy in the era of the 4th industrial revolution. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 165, 120558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.-C.; Bejan, B.M.; Tipi, N. Generation X versus Millennials communication behaviour on social media when purchasing food versus tourist services. E+ M Ekon. A Manag. 2018, 21, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rayp, G. Do consumers care about ethics? Willingness to pay for fair-trade coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D. Ethical Determinants for Generations X and Y. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Pezzetti, R.; Grechi, D. Trends in the Fashion Industry. The Perception of Sustainability and Circular Economy: A Gender/Generation Quantitative Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapibul, M.; Lacka, E.; Wang, X.; Chan, H.K. An empirical investigation of green purchase behaviour among the young generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, M. Compassion without action: Examining the young consumers consumption and attitude to sustainable consumption. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Jin, B. A theoretical investigation of slow fashion: Sustainable future of the apparel industry. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, L.; Lindh, C. The sustainability-age dilemma: A theory of (un)planned behaviour via influencers. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, e127–e139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, E.S.; Cioca, L.-I.; Dan, V.; Ciomos, A.O.; Crisan, O.A.; Barsan, G. Studies and investigation about the attitude towards sustainable production, consumption and waste generation in line with circular economy in Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, Z.A.; Çımrin, F.K.; Doğan, O. Gender, generation and sustainable consumption: Exploring the behaviour of consumers from Izmir, Turkey. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.-C. Enhancing green loyalty towards apparel retail stores: A cross-generational analysis on an emerging market. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2018, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.-N.; Michaut-Denizeau, A. Are millennials really more sensitive to sustainable luxury? A cross-generational international comparison of sustainability consciousness when buying luxury. J. Brand Manag. 2020, 27, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Pucci, T.; Aquilani, B.; Zanni, L. Millennial Generation and Environmental Sustainability: The Role of Social Media in the Consumer Purchasing Behavior for Wine. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G. Moving Beyond Multiple Regression Analysis to Algorithms: Calling for Adoption of a Paradigm Shift from Symmetric to Asymmetric Thinking in Data Analysis and Crafting Theory; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beak, Y.; Kim, K.; Maeng, K.; Cho, Y. Is the environment-friendly factor attractive to customers when purchasing electric vehicles? Evidence from South Korea. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 996–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerding, S.G.; Merz, N. Consumer preferences for organic labels in Germany using the example of apples—Combining choice-based conjoint analysis and eye-tracking measurements. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, C.; Emberger-Klein, A.; Menrad, K. Consumer preferences for outdoor sporting equipment made of bio-based plastics: Results of a choice-based-conjoint experiment in Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Lessem, N. Eco-Premium or Eco-Penalty? Eco-Labels and Quality in the Organic Wine Market. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 318–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Y.-C.; Chiang, T.-F.; Chang, S.-M. Is what you choose what you want?—Outlier detection in choice-based conjoint analysis. Mark. Lett. 2017, 28, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, S.W.; Meissner, M.; Decker, R. Measuring Consumer Preferences for Complex Products: A Compositional Approach Based on Paired Comparisons. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbride, T.J.; Allenby, G.M. A Choice Model with Conjunctive, Disjunctive, and Compensatory Screening Rules. Mark. Sci. 2004, 23, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.; Watson, V.; Entwistle, V. Rationalising the ‘irrational’: A think aloud study of discrete choice experiment responses. Health Econ. 2009, 18, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, M.; Dahan, E.; Hauser, J.R.; Orlin, J. Greedoid-Based Noncompensatory Inference. Mark. Sci. 2007, 26, 532–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shocker, A.D.; Ben-Akiva, M.; Boccara, B.; Nedungadi, P. Consideration set influences on consumer decision-making and choice: Issues, models, and suggestions. Mark. Lett. 1991, 2, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turley, L.W.; LeBlanc, R.P. Evoked sets: A dynamic process model. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1995, 3, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.B.; Baier, D. Adaptive CBC: Are the Benefits Justifying its Additional Efforts Compared to CBC? Arch. Data Sci. Ser. A 2020, 6, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.M.; Orme, B.K. (Eds.) A New Approach to Adaptive CBC; Sawtooth Software Conference Proceedings: Sequim, WA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sawtooth Software Inc. The Adaptive Choice-Based Conjoint (ACBC) Technical Paper. Available online: https://www.sawtoothsoftware.com/download/techpap/acbctech2014.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2020).

- Brand, M.B.; Rausch, T.M. Examining sustainability surcharges for outdoor apparel using Adaptive Choice-Based Conjoint analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 125654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronda, L.; Abril, C.; Valor, C. Job choice decisions: Understanding the role of nonnegotiable attributes and trade-offs in effective segmentation. Manag. Decis. 2020, 59, 1546–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocquyt, A.; Crucke, S.; Slabbinck, H. Organizational characteristics explaining participation in sustainable business models in the sharing economy: Evidence from the fashion industry using conjoint analysis. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2603–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnen, G.; Hille, S.L.; Wittmer, A. Willingness to pay for green products in air travel: Ready for take-off? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W.; Engel, J.F. Consumer Behavior; Cengage Learning India: New Delhi, India, 2006; ISBN 9788131505243. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, J.F.; Kollat, D.T.; Blackwell, R.D. Consumer Behavior; Holt Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1968; ISBN 0-03-910136-3. [Google Scholar]

- Moe, W.W. An Empirical Two-Stage Choice Model with Varying Decision Rules Applied to Internet Clickstream Data. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, F.; Sattler, H. Preference Measurement with Conjoint Analysis. Overview of State-of-the-Art Approaches and Recent Developments. GfK Mark. Intell. Rev. 2011, 3, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C.E.; Deal, K.; Chen, Y. Adaptive choice-based conjoint analysis: A new patient-centered approach to the assessment of health service preferences. Patient 2010, 3, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.; Menrad, K.; Decker, T. Adaptive Hybrid Methods for Choice-Based Conjoint Analysis: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2015, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chapman, C.N.; Alford, J.L.; Johnson, C.; Lahav, M.; Weidemann, R. (Eds.) Comparing Results of CBC and ACBC with Real Product Selection. In Proceedings of the 2009 Sawtooth Software Conference; Sawtooth Software, Inc: Florida, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jervis, S.M.; Ennis, J.M.; Drake, M.A. A Comparison of Adaptive Choice-Based Conjoint and Choice-Based Conjoint to Determine Key Choice Attributes of Sour Cream with Limited Sample Size. J. Sens. Stud. 2012, 27, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salm, S.; Hille, S.L.; Wüstenhagen, R. What are retail investors’ risk-return preferences towards renewable energy projects? A choice experiment in Germany. Energy Policy 2016, 97, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orme, B.K.; Johnson, R.M. Testing Adaptive CBC: Shorter Questionnaires and BYO vs.‘Most Likelies’; Research Paper; Sawtooth Software Series: Sequim, WA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wackershauser, V.; Lichters, M.; Vogt, B. (Eds.) Predictive Validity in Choice-Based Conjoint Analysis: A Comparison of Hypothetical and Incentive-Aligned ACBC with Incentive-Aligned CBC: An Abstract; Academy of Marketing Science Annual Conference; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Strutton, D.; Pelton, L.E.; Ferrell, O.C. Ethical behavior in retail settings: Is there a generation gap? J. Bus. Ethics 1997, 16, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, F.F.; Emberger-Klein, A.; Menrad, K. Indicators of Consumers’ Preferences for Bio-Based Apparel: A German Case Study with a Functional Rain Jacket Made of Bioplastic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderjahn, I.; Peyer, M.; Seegebarth, B.; Wiedmann, K.-P.; Weber, A. The many faces of sustainability-conscious consumers: A category-independent typology. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 91, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viciunaite, V.; Alfnes, F. Informing sustainable business models with a consumer preference perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Qian, L.; Tyfield, D.; Soopramanien, D. On the heterogeneity in consumer preferences for electric vehicles across generations and cities in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 167, 120687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, D.; Rausch, T.M.; Wagner, T.F. The Drivers of Sustainable Apparel and Sportswear Consumption: A Segmented Kano Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paetz, F.; Guhl, D. Understanding Differences in Segment-specific Willingness-to-pay for the Fair Trade Label. Mark. ZFP 2017, 39, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Steiner, M.; Helm, R.; Hüttl-Maack, V. A customer-based approach for selecting attributes and levels for preference measurement and new product development. Int. J. Prod. Dev. 2016, 21, 233–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L.; Spanish, M.T. Focus groups: A new tool for qualitative research. Qual. Sociol. 1984, 7, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEVH. Product Groups Ranked by Online Retail Revenue in Germany in 2018 and 2019. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/451868/best-selling-product-groups-by-revenue-in-online-retail-in-germany/ (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Jaller, M.; Pahwa, A. Evaluating the environmental impacts of online shopping: A behavioral and transportation approach. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 80, 102223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, S.M.; Winer, R.S. The Role of the Beneficiary in Willingness to Pay for Socially Responsible Products: A Meta-analysis. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goworek, H.; Fisher, T.; Cooper, T.; Woodward, S.; Hiller, A. The sustainable clothing market: An evaluation of potential strategies for UK retailers. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 935–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Lee, H.-H. Young Generation Y consumers’ perceptions of sustainability in the apparel industry. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 16, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, M.; Vecchi, A. Close the loop: Evidence on the implementation of the circular economy from the Italian fashion industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 856–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Billah, M.M.; Hack-Polay, D.; Alam, A. The use of biotechnologies in textile processing and environmental sustainability: An emerging market context. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 159, 120204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Ha-Brookshire, J.; Chow, P.-S. The moral responsibility of corporate sustainability as perceived by fashion retail employees: A USA-China cross-cultural comparison study. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1462–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.-W.; Park, S.; Ha-Brookshire, J.E. Toward a circular economy: Understanding consumers’ moral stance on corporations’ and individuals’ responsibilities in creating a circular fashion economy. Bus. Strategy. Environ. 2021, 30, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.; Rothenberg, L. An assessment of organic apparel, environmental beliefs and consumer preferences via fashion innovativeness. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.; Abraham, L. Effect of knowledge on decision making in the context of organic cotton clothing. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börjeson, N.; Boström, M. Towards Reflexive Responsibility in a Textile Supply Chain. Bus. Strategy. Env. 2018, 27, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballet, J.; Bhukuth, A.; Carimentrand, A. Child Labor and Responsible Consumers. Bus. Soc. 2014, 53, 71–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currim, I.S.; Weinberg, C.B.; Wittink, D.R. Design of subscription programs for a performing arts series. J. Consum. Res. 1981, 8, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, L.N. Examining the Impact of Moral Imagination on Organizational Decision Making. Bus. Soc. 2015, 54, 254–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, A.M. Competition Among Self-Regulatory Institutions. Bus. Soc. 2013, 52, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekker, S.A.C.; Humphrey, J.E.; O’Brien, K.R. Do Sustainability Rating Schemes Capture Climate Goals? Bus. Soc. 2021, 60, 125–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, T.M.; Kopplin, C.S. Bridge the gap: Consumers’ purchase intention and behavior regarding sustainable clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.; Henry, B. Does Use Matter? Comparison of Environmental Impacts of Clothing Based on Fiber Type. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.Q.; Hoang, V.-N.; Wilson, C.; Nguyen, T.-T. Eco-efficiency analysis of sustainability-certified coffee production in Vietnam. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janßen, D.; Langen, N. The bunch of sustainability labels—Do consumers differentiate? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 1233–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, I.E.; Tsalis, T. A framework to evaluate eco- and social-labels for designing a sustainability consumption label to measure strong sustainability impact of firms/products. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, A.; Teichmann, K. A facts panel on corporate social and environmental behavior: Decreasing information asymmetries between producers and consumers through product labeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöckigt, G.; Schiebener, J.; Brand, M. Providing sustainability information in shopping situations contributes to sustainable decision making: An empirical study with choice-based conjoint analyses. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.S.; Byun, S.-E. Are consumers willing to go the extra mile for fair trade products made in a developing country? A comparison with made in USA products at different prices. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedermeier, A.; Emberger-Klein, A.; Menrad, K. Which factors distinguish the different consumer segments of green fast-moving consumer goods in Germany? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 1823–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.A.; Arthurs, J.D.; Treviño, L.J.; Joireman, J. Consumer animosity in the global value chain: The effect of international production shifts on willingness to purchase hybrid products. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.E. On the Design of Choice Experiments Involving Multifactor Alternatives. J. Consum. Res. 1974, 1, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhfeld, W.F.; Tobias, R.D.; Garratt, M. Efficient Experimental Design with Marketing Research Applications. J. Mark. Res. 1994, 31, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R. Millennial generation attitudes to sustainable wine: An exploratory study on Italian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orme, B. Getting Started with Conjoint Analysis: Strategies for Product Design and Pricing Research, 4th ed.; Research Publishers LLC: Madison, WI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wuebker, R.; Hampl, N.; Wuestenhagen, R. The strength of strong ties in an emerging industry: Experimental evidence of the effects of status hierarchies and personal ties in venture capitalist decision making. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2015, 9, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allenby, G.; Fennell, G.; Huber, J.; Eagle, T.; Gilbride, T.; Horsky, D.; Kim, J.; Lenk, P.; Johnson, R.; Ofek, E.; et al. Adjusting Choice Models to Better Predict Market Behavior. Mark. Lett. 2005, 16, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D. Conditional Logit Analysis of Qualitative Choice Behavior; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Hensher, D.A.; Rose, J.M.; Greene, W.H. Applied Choice Analysis: A Primer, Transferred to Digital Printing; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. ISBN 978052160 5779.

- Kalwani, M.U.; Meyer, R.J.; Morrison, D.G. Benchmarks for Discrete Choice Models. J. Mark. Res. 1994, 31, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.; Wittink, D.R.; Fiedler, J.A.; Miller, R. The Effectiveness of Alternative Preference Elicitation Procedures in Predicting Choice. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlömert, N.; Eggers, F. Predicting new service adoption with conjoint analysis: External validity of BDM-based incentive-aligned and dual-response choice designs. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Oakland, CA, USA, 1 January 1967; Lecam, L., Neyman, J., Eds.; University of California: Oakland, CA, USA; pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Niinimäki, K. Eco-clothing, consumer identity and ideology. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, A.R.; Wilkie, J.E.B.; Ma, J.; Isaac, M.S.; Gal, D. Is Eco-Friendly Unmanly? The Green-Feminine Stereotype and Its Effect on Sustainable Consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzone, L.; Hilton, D.; Sale, L.; Cohen, D. Socio-demographics, implicit attitudes, explicit attitudes, and sustainable consumption in supermarket shopping. J. Econ. Psychol. 2016, 55, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarti, S.; Darnall, N.; Testa, F. Market segmentation of consumers based on their actual sustainability and health-related purchases. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 192, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Grant, L.E. Eco-labeling strategies and price-premium: The wine industry puzzle. Bus. Soc. 2014, 53, 6–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiaracina, R.; Marchet, G.; Perotti, S.; Tumino, A. A review of the environmental implications of B2C e-commerce: A logistics perspective. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2015, 45, 565–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes, E.; Tchetchik, A. The role of electronic word of mouth in reducing information asymmetry: An empirical investigation of online hotel booking. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 85, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. Greenwash and Green Trust: The Mediation Effects of Green Consumer Confusion and Green Perceived Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, J.E.; Vakharia, A.J.; Wang, R. Environmental implications for online retailing. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 239, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pålsson, H.; Pettersson, F.; Hiselius, L.W. Energy consumption in e-commerce versus conventional trade channels-Insights into packaging, the last mile, unsold products and product returns. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product Features | Feature Characteristics (Max. Score 24) |

|---|---|

| Features and quality issues | Waterproof (21) |

| Windproof (20) | |

| Water-repellent (20) | |

| High water column (17) | |

| Durable (16) | |

| Functional (15) | |

| Low weight (11) | |

| Small pack size (9) | |

| Materials and manufacturing process | Workmanship (20) |

| Recycled materials (17) | |

| Fair production (17) | |

| Applied materials (17) | |

| Regenerative resources (15) | |

| Free of PFC (12) | |

| Transparent manufacturing processes (12) | |

| Price | Price performance ratio (16) |

| Discounts (9) | |

| Design | Look/Visual appearance (19) |

| Fitting (17) | |

| Colored (−5) | |

| Labels | Fair Wear Foundation label (15) |

| Bluesign label (10) | |

| ‚Grüner Knopf‘ (‘Green Button’) label (9) | |

| Green Shape label (5) | |

| Country-of-origin | Transparent information about product (18) |

| Produced in Europe (11) | |

| Place of manufacture (8) | |

| Sent from Germany (7) | |

| Brand proposition | Warranty (14) |

| Sustainable brand philosophy (13) | |

| Service (e.g., repair in case of deterioration) (12) | |

| Campaigns for environmental protection (8) | |

| Online service | Good online customer ratings (16) |

| Repair services (14) | |

| Free returns (13) | |

| Plastic-free packaging for delivery (12) | |

| Product test judgments (9) | |

| Climate-neutral delivery (9) | |

| Resale of returned products (9) | |

| Replacement services (8) | |

| Place of shipment (4) |

| Attribute | Attribute Levels | References |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Regular fit in black; Slim fit in black; Regular fit colored; Slim fit colored | [96]; [104]; Focus group |

| Functionality | - Waterproof, windproof, breathable - Waterproof, windproof, breathable, minimized package size - Waterproof, windproof, breathable, minimized package size, low weight | [15]; [105]; Focus group |

| Materials (major proportion) | Synthetical materials; Recycled materials; Bio-based materials | [79]; [51]; Focus group |

| Eco-labels | No eco-labels; Bluesign label OEKO-TEX label | [106]; [107]; Partwise focus group |

| Social Labels | No social labels; Fair Wear Foundation label Fair Trade Certified label | [108]; [109,110]; Focus group |

| Country-of-origin | Made in Asia; Made in Europe; Made in Germany | [50,111]; Focus group |

| Price | 79.00 EUR; 119.00 EUR; 159.00 EUR; 199.00 EUR | [66]; [112]; Focus group |

| Variables | None-Option F Value | Importance of Eco-Labels F Value | Importance of Social Labels F Value | Importance of Price F Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EnSC (mean = 3.64) 2 | 5.897 1,* | 27.155 1,*** | 17.325 1,*** | 28.178 *** |

| SoSC (mean = 3.21) 2 | 3.209 1 | 24.331 1,*** | 31.707 1,*** | 43.698 *** |

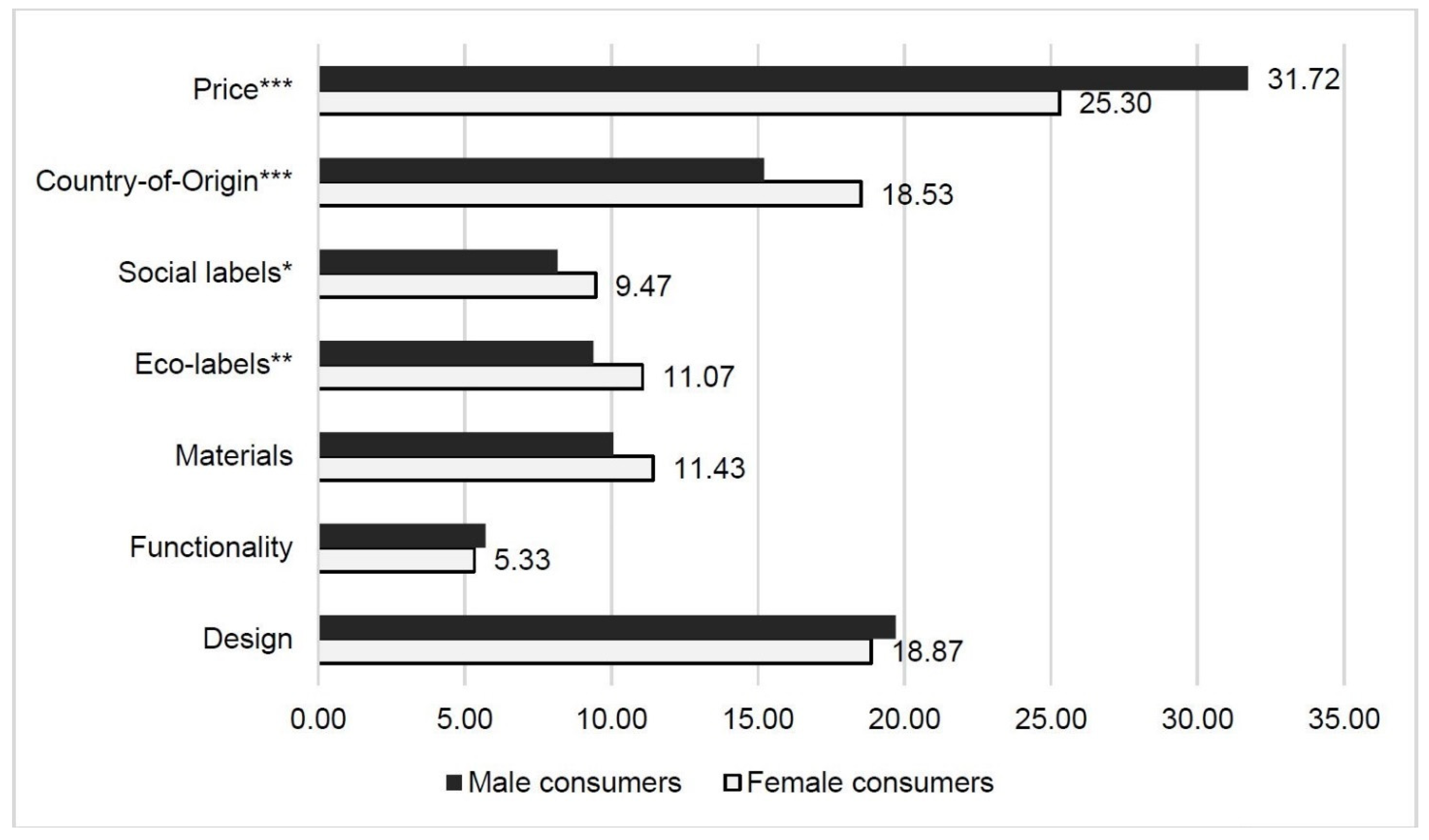

| Gender | 0.182 | 9.612 1,** | 5.834 * | 14.930 *** |

| Factor | Segment 1 | Segment 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Design | 21.49 | 16.75 |

| Functionality | 5.56 | 5.47 |

| Materials | 13.57 | 7.53 |

| Eco-Labels | 12.04 | 8.17 |

| Social labels | 10.15 | 7.31 |

| Country-of-Origin | 20.38 | 12.89 |

| Price | 16.81 | 41.87 |

| Variables | None-Option F Value | Importance of Eco-Labels F Value | Importance of Social Labels F Value | Importance of Price F Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EnSC (mean = 3.22) 2 | 2.027 | 13.107 1,*** | 8.770 ** | 15.844 *** |

| SoSC (mean = 2.76) 2 | 0.019 | 7.134 ** | 4.935 * | 9.468 ** |

| Gender 3 | 0.013 | 5.565 * | 3.486 1 | 0.003 |

| Factor | Segment 1 | Segment 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Design | 23.68 | 17.14 |

| Functionality | 7.50 | 6.15 |

| Materials | 11.14 | 7.53 |

| Eco-Labels | 12.51 | 8.32 |

| Social labels | 11.88 | 8.08 |

| Country-of-Origin | 18.68 | 12.54 |

| Price | 14.60 | 40.24 |

| Hypotheses | Confirmed/ Rejected | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | For Xers, the importance of price is higher for consumers less concerned about ecological sustainability compared to very concerned consumers. | Confirmed | <0.001 |

| H1b | For Zers, the importance of price is higher for consumers less concerned about ecological sustainability compared to very concerned consumers. | Confirmed | <0.001 |

| H2a | For Xers, the importance of price is higher for consumers less concerned about social sustainability compared to very concerned consumers. | Confirmed | <0.001 |

| H2b | For Zers, the importance of price is higher for consumers less concerned about social sustainability compared to very concerned consumers. | Confirmed | 0.002 |

| H3a | The importance of eco-labels is higher among Zers compared to Xers. | Rejected | 0.546 |

| H3b | The importance of social labels is higher among Zers compared to Xers. | Confirmed | 0.001 |

| H4 | The importance of price is higher for consumers of Generation X compared to consumers of Generation Z. | Confirmed | 0.042 |

| H5a | The importance of price is higher for men than for women among Generation X. | Confirmed | <0.001 |

| H5b | The importance of price is higher for men than for women among Generation Z. | Rejected | 0.995 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brand, B.M.; Rausch, T.M.; Brandel, J. The Importance of Sustainability Aspects When Purchasing Online: Comparing Generation X and Generation Z. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5689. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095689

Brand BM, Rausch TM, Brandel J. The Importance of Sustainability Aspects When Purchasing Online: Comparing Generation X and Generation Z. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5689. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095689

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrand, Benedikt M., Theresa Maria Rausch, and Jannika Brandel. 2022. "The Importance of Sustainability Aspects When Purchasing Online: Comparing Generation X and Generation Z" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5689. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095689

APA StyleBrand, B. M., Rausch, T. M., & Brandel, J. (2022). The Importance of Sustainability Aspects When Purchasing Online: Comparing Generation X and Generation Z. Sustainability, 14(9), 5689. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095689