Households Social Vulnerability to Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies in Raya Kobo and Raya Alamata Woredas, Ethiopia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area Setting

2.2. Sample Size Determination

2.3. Sampling Procudure

2.4. Procedure of Matching Strategy

Assumption of Conditional Independence and Common Support

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Socio-Economic and Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

3.2. Land Tenure

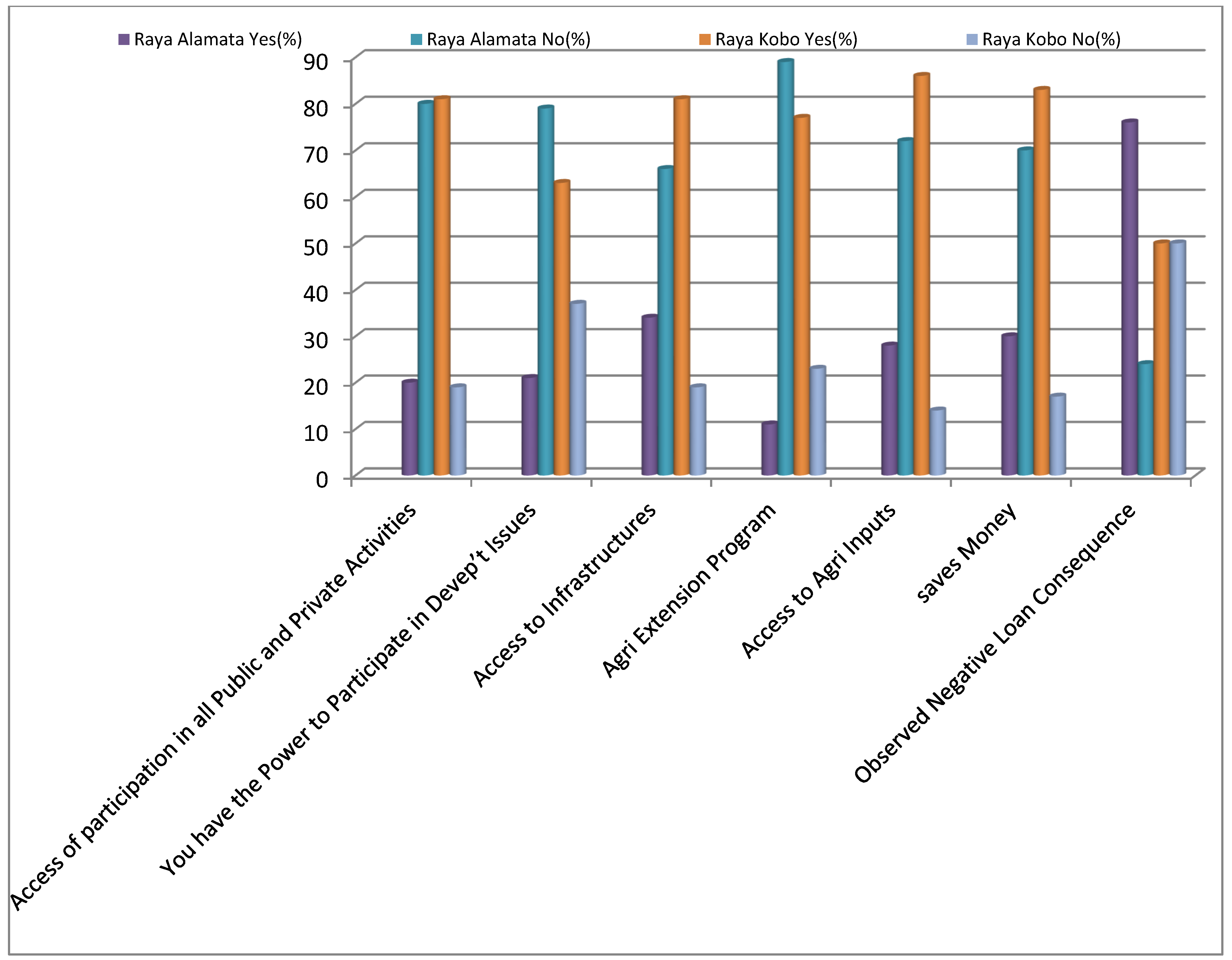

3.3. Differences in Social Vulnerability and Use of Agricultural Inputs as Food Security Determinants

3.4. Differecnes in Social Vulnerability on Production and Productivity

3.5. Food Security Status of Households in the Study Area

3.6. Social Vulnerability Dimensions and Food Insecurity in the Study Area

3.7. Food Coping Strategy of Households in the Study Area

3.8. Determinant Factors to Household Food Security in the Study Area

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

4.1. Conclusions

4.2. Recommnendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items | Sample Households (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raya Alamata = N = 124 | Raya Kobo N = 276 | ||||||

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | ||

| Age | 15 to 64 | 41.05 | 11.58 | 52.63 | 31.01 | 5.42 | 35.66 |

| Above 64 | 42.11 | 5.26 | 47.37 | 56.59 | 6.98 | 64.34 | |

| Average family size (No.) | 3.16 | 3.25 | 6.33 | 2.69 | 2.63 | 5.02 | |

| Marital status | married | 33.33 | 84.76 | 84.76 | |||

| single | 54.76 | 6.19 | 6.19 | ||||

| High school completed | 6.52 | 26.76 | |||||

| Raya Alamata (%) | Raya Kobo (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | |

| Access to irrgation | 8.18 | 68.20 | |||||

| Irrigation affordability | |||||||

| Can afford | 69.9 | 95.4 | |||||

| Can not afford | 30.1 | 4.6 | |||||

| Access to extension service | 1.82 | 49.43 | |||||

| Access to improved seed | 0.91 | 51.34 | |||||

| Access to fertilizer | 1.82 | 48.66 | |||||

| Access to pecticide | 0.00 | 30.65 | |||||

| Manure application | 0.91 | 18.01 | |||||

| Income | Agri | 80.9 | 83.14 | ||||

| Pt-T | 7.27 | 0.00 | |||||

| Agri and Pt-T | 10.91 | 16.48 | |||||

| Others | 0.91 | 0.91 | |||||

| Own land | 68.18 | 85 | 81.8 | 81.8 | 30.3 | 44.3 | |

| Land Rented from HHs | 27.27 | 30.68 | 30 | 30 | 33.33 | 20.61 | |

| Land rented from institutions | 13.6 | 7.8 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 24.24 | 23.25 | |

| Productivity trend | |||||||

| Increase | 3.5 | 54.72 | |||||

| Decrease | 96.5 | 45.28 | |||||

References

- Relief Society of Tigray. Feasibility Study Report for Raya Valley Agricultural Development Project, Volume III, Annex J, Agronomy and Crop Production; Relief Society of Tigray: Mekelle, Ethiopia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Khandker; Shahidur, R.; Koolwal Gayatri, B.; Samad Hussain, A. Handbook on Impact Evaluation: Quantitative Methods and Practices; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Relief Society of Tigray. Raya Valley Development Study Project Demographic and Social Baseline Survey Report; Relief Society of Tigray: Alamata, Ethiopia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture. Productive Safety Net Programme Phase IV Programme Implementation Manual; Ministry of Agriculture: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Water and Energy. Water and Energy Development Office Annual Report; Ministry of Water and Energy: Alamata, Ethiopia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Amhara Regional State: Urban Rural Road Authority Project (URRAP) Annual Report; ANRS: Kobo, Ethiopia, 2019.

- Raya Kobo Woreda Agriculture Office Annual Report; ANRS: Kobo, Ethiopia, 2019.

- Allen, K. Vulnerability Reduction and the Community-Based Approach. In Natural Disasters and Development in a Globalized World; Pelling, M., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 170–184. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N. Social Vulnerability to Climate Change and Extremes in Coastal Vietnam. World Dev. 1999, 27, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Huq, S.; Brown, K.; Conway, D.; Hulme, M. Adaptation to Climate Change: Setting the Agenda for Development Policy and, Research; Center for Climate Change Research Working Paper: Tyndall, SD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Brown, K.; Nelson, D.R.; Berkes, F.; Eakin, H.; Folke, C.; Galvin, K.; Gunderson, L.; Goulden, M.; O’Brien, K.; et al. Resilience implications of policy responses to climate change. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I.; Wisner, B. At Risk: Natural Hazards, Peoples Vulnerability, and Disasters; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, P.M.; Adger, W.N. Theory and practice in assessing vulnerability to climate change and facilitating adaptation. Clim. Chang. 2000, 47, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, K. Disasters in ‘development’ contexts: Contradictions and options for a prevention approach. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 1997, 5, a91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fatemi, F.; Ardalana, A.; Aguirre, B.; Mansouri, N.; Mohammadfam, I. Social vulnerability indicators in disasters: Findings from a systematic Review: Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 22, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, B.; Luce, H.R. Disaster Vulnerability: Scale, Power and Daily Life. GeoJournal 1993, 30, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HLPE. Social Protection for Food Security; High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Degefa, T. Rural Livelihoods, Poverty and Food Security in Ethiopia. A Case Study at Erenssa and Garbi Communities in Oromia Zone, Amhara National Regional State. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Geography, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; Ministry of Finance and Economic Development: Kampala, Uganda, 2013.

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Human Development Report (HDI) Report; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture. Poverty and Hunger Strategic Review: Ethiopia’s Roadmap to Achieve Zero Poverty and Hanger Report; Ministry of Agriculture: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Diriba, G. Overcoming Agricultural and Food Crises in Ethiopia: Institutional Evolution and the Path to Agricultural Transformation; Ministry of Agriculture: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.A. Food Security Situation in Ethiopia. A Review Study. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328908922 (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- FAO STAT. Agricultural Production Statistics 2000–2020 FAOSTAT Analytical Brief 41; FAOSTAT: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ACAPS. Food Insecurity. ACAPS Thematic Report: Famine in Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, and Yemen. 2018. Available online: https://www.acaps.org/sites/acaps/files/slides/files/20180226_acaps_thematic_report_food_insecurity_final.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Abdulla, A.M. Determinants of Household Food Security and Coping Strategies: The Case of BuleHora District, Borana Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Eur. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 3, 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.B.; Woodrow, P.J. Reducing Vulnerability to drought and famine; developmental approaches to relief. Disasters 1991, 15, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I.; Wisner, B. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Climate Risk and Food Security in Ethiopia: Analysis of Climate Impacts on Food Security and Livelihoods. Global Early Warning–Early Action Report on Food Security and Agriculture. 2016. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-early-warning (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, J.J.; Ichimura, H.; Todd, P. Matching as an Econometric Evaluation Estimator: The Review of Economic Studies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; Volume 65, pp. 261–294. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. Pastoralism in Africa’s Drylands: Reducing Risks, Addressing Vulnerability and Enhancing Resilience; The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World: Rome, Italy, 2017; 52p. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Health Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux, S. Theories of Famine; Harvester Wheatsheaf: Hemel Hempstead, UK, 1993; 221p. [Google Scholar]

- Feed the Future; Global Food Security Strategy (GFSS): Global Report on Food Crises. 2018. Available online: https://www.fsinplatform.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/GRFC_2018_Full_report_EN_Low_resolution.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Raya Alamata wereda Administration Office Annual Report; Raya Alamata Wereda Adminstrative Office: Alamata, Ethiopia, 2019.

- Maxwell, D. The “Coping Strategies Index” Introduction and Overview; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yimer, M. Towards Food Insecurity Multidimensional Index. 2015. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Towards-a-Food-Insecurity-Multidimensional-Index-(-NapoliMuro/e37dad6f2c3e6d3f159ab68e6c7867b3ea3034ad (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Central Statistics Agency (CSA), Ethiopia; ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016; HIV Report; CSA: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; ICF: Rockville, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WFP. Saving Lives and Changing Lives, Ethiopia Annual Country Report of 2019 Country Strategic Plan; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yimer, M. Pastoral Development Pathways in Ethiopia; the Policy Environment and Critical Constraints, Brief for GSDR. 2017. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5789pastoralism_development_pathways_rev2.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Meade, B. Ethiopia’s Progress towards Eradicating Poverty: An Interim Report on 2015/16 Poverty Analysis Study; UNDP: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture. Office of Agriculture and Rural Development Annual Report; Ministry of Agriculture: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, D.; Caldwell, R. The Coping Strategies Index Field Methods Manual, 2nd ed.; USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Helvetas, P.M.; von Grebmer, K.; Bernstein, J.; Patterson, F.; Wiemers, M.; Chéilleachair, R.N.; Foley, C.; Gitter, S.; Ekstrom, K.; Fritschel, H. Global Hunger Index: The Challenge of Hunger and Climate Change; Global Hunger Index; GHI: Dublin, Ireland; Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dan Maxwell, S.; Smith, M. Household Food Security. Concepts Indicators Measurements. A Technical Review; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA; IFAD: Rome, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Coats, J.; Swindale, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Household Food Access; Indicator Guide (V.3); Food and Nutrition Technical Assistant Project; Academy for Educational Developmen: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- FDRE, Humanitarian Partners. Joint Government and Humanitarian Partners’ Requirement Document; Government of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tigray Regional National State. Tigray Finance and Economic Development Bureau Strategic Plan; Tigray Regional National State: Mekelle, Ethiopia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- KGVD. Kobo Grana Valley Development Project Annual Report; North Wollo: Kobo, Ethiopia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Water Works Design & Supervision Enterprise (WWDSE). Raya Valley Pressurized Irrigation Project, Socioeconomic Feasibility Report; WWDSE: Mekele, Ethiopia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Debebe, H. Food Security: A Brief Review of Concepts and Indicators. In Proceedings of the Inaugural and First Annual Conference of the Agricultural Economic Society of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 8–9 June 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mariam, M.W. Rural Vulnerability to Famine in Ethiopia, 1958–1977; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

| Tabias | Population Size | Sampled Households |

|---|---|---|

| Total | Total | |

| Amhara region | 222,534 | 274 |

| Tigray region | 102,398 | 126 |

| Total | 324,932 | 400 |

| Land Fertility % | Raya Almata | Raya Kobo | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowland | Highland | Lowland | Highland | |

| Infertile | 8% | 38% | 13% | 14% |

| Medium | 75% | 54% | 40% | 81% |

| fertile | 17% | 8% | 47% | 5% |

| 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| Indicators/Group | Treated (Raya-Kobo) | No-Treated (Raya-Alamata) | Combined | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to irrigation | 0.44 | 0.018 | 0.31 | 0.42 *** |

| Better extension service | 0.49 | 0.018 | 0.35 | 0.47 *** |

| Access to improved seed | 0.51 | 0.009 | 0.36 | 0.50 *** |

| Access to fertilizer | 0.48 | 0.009 | 0.34 | 0.47 *** |

| Access to pecticide | 0.30 | 0 | 0.21 | 0.30 *** |

| Application of manure | 0.17 | 0.009 | 0.21 | 0.17 *** |

| Land ownership | ||||

| Land size | 1.13 | 1.64 | 1.27 | −0.50 *** |

| Own land | 0.42 | 0.81 | 0.54 | −0.39 *** |

| Land Rented from HHs | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.24 | −0.078 |

| Land rented from institutions | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.14 ** |

| Share cropping | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.13 |

| Production/productivity trend | ||||

| Total Production per hectare | 22.51 | 19.54 | 21.65 | −2.96 |

| Productivity | 0.55 | 0.029 | 0.40 | −0.52 *** |

| Irrigation infrastructure availability and affordability | ||||

| Irrigation system availability (Can afford) | 0.24 | 0.60 | 0.34 | 0.35 *** |

| Cannot afford even if there is the system | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.26 *** |

| Food Security Status | Raya Alamata | Raya Kobo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Land | High Land | % | Low Land | High Land | % | |

| Food secure | 10% | 6.4% | 16.4% | 40.23% | 36.40% | 76.63% |

| Mildly food insecure | 12.7% | 4.5% | 17.3% | 2.68% | 3.45% | 6.13% |

| Moderately food insecure | 41.8% | 11.8% | 53.6% | 6.13% | 10.34% | 16.47% |

| Severely food insecure | 10% | 2.7% | 12.8% | 0.38% | 0.38% | 0.76% |

| Variables | Sample | ATT | Difference (S.E) | T-Stat | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated RK | No-Treated RA | Treated RK | No-Treated RA | |||

| FS_Status | 261 | 110 | 1.43 | 2.76 | −1.35 (0.29) | −4.54 **** |

| HFIAS_Score | 261 | 110 | 3.70 | 10.58 | −6.87 (1.50) | −4.59 *** |

| HFIAS_Cat1 | 261 | 110 | 0.66 | 0.32 | 0.33 (0.12) | 2.76 ** |

| HFIAS_Cat2 | 261 | 110 | 0.30 | 0.76 | −046 (0.10) | −4.23 *** |

| HFIAS_Cat3 | 261 | 110 | 0.33 | 0.77 | −0.43 (0.09) | −4.66 *** |

| HFIAS_Cat4 | 261 | 110 | 0.19 | 0.68 | −0.48 (0.12) | −4.01 *** |

| Variables | Raya Alamata | Raya Kobo | Chi-Squared Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | ||

| Access to participates in all Public and Private Activities | 20 | 80 | 81 | 19 | p = 0.0000 |

| You have the Power to Participate in Development Issues | 21 | 79 | 63 | 37 | p = 0.0000 |

| Access to Infrastructures | 34 | 66 | 81 | 19 | p = 0.0000 |

| Transportation to Market Places | 36 | 64 | 74 | 26 | p = 0.0000 |

| Agri Extension Program | 11 | 89 | 77 | 23 | p = 0.0000 |

| Access to Agri Inputs | 28 | 72 | 86 | 14 | p = 0.0000 |

| Credit Provider—Cooperatives | 7 | 93 | 21 | 79 | p= 0.0012 |

| Credit Provider—NGOs | 2 | 98 | 5 | 95 | p = 0.1578 |

| Credit Provider—Relatives | 2 | 98 | 8 | 92 | p = 0.0231 |

| Saves Money | 30 | 70 | 83 | 17 | p = 0.0000 |

| Loan access for Non-Farm and Off-Farms Activities | 32 | 68 | 61 | 39 | p = 0.0000 |

| Loan Access from Microfinance | 58 | 42 | 40 | 60 | p = 0.0039 |

| Observed Negative Loan Consequence | 76 | 24 | 50 | 50 | p = 0.0004 |

| Loan for Ceremonial Event | 28 | 72 | 5 | 95 | p = 0.0000 |

| Loan for Sending Children to Arab | 25 | 75 | 3 | 97 | p = 0.0000 |

| Loan for Purchase of Productive Assets | 24 | 76 | 25 | 75 | p = 0.7221 |

| Loan for Food Purchase | 51 | 49 | 20 | 80 | p = 0.0000 |

| Copping Strategies | Raya Kobo (%) | Raya Alamata% |

|---|---|---|

| Decrease_No_Meal | 23.7 | 79.1 |

| Decrease_Quality and Quantity | 27.9 | 71.8 |

| Local Labor | 80.2 | 50.9 |

| Loan from micro finance | 64.9 | 60 |

| Selling productive assets | 37.0 | 47.3 |

| Dropping_Children_out of School | 38.9 | 44.5 |

| Migration | 55.0 | 13.6 |

| Sending_HH_member | 40.8 | 34.5 |

| Tradional_loan | 34.7 | 39.1 |

| Remittance | 25.6 | 33.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hidaru, A.; Tolossa, D.; Tilahun, T. Households Social Vulnerability to Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies in Raya Kobo and Raya Alamata Woredas, Ethiopia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010160

Hidaru A, Tolossa D, Tilahun T. Households Social Vulnerability to Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies in Raya Kobo and Raya Alamata Woredas, Ethiopia. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010160

Chicago/Turabian StyleHidaru, Agezew, Degefa Tolossa, and Temesgen Tilahun. 2023. "Households Social Vulnerability to Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies in Raya Kobo and Raya Alamata Woredas, Ethiopia" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010160