Abstract

With the rise of the circular economy, recycling, and upcycling is an emerging sustainable system in the fashion industry, emphasising a closed loop of “design, produce, use, and recycle”. In this context, this paper will explore community-based approaches to scale up clothing reuse and upcycling under a social innovation perspective. This study aims to establish community-based practice models, which contribute toward promoting a greater understanding of sustainable fashion and achieving collaborative cocreation frameworks for community stakeholders. This paper, therefore, takes a social innovation perspective to conduct design studies helping with the technical (problem-solving) and cultural (sense-making) barriers that clothing reuse and upcycling face. The research was conducted in the context of the Shanghai community, and a large amount of first-hand research data were obtained through field research, expert and user interviews, and participatory workshops. Finally, this research establishes a platform proposal which combines strategic service design and practical toolkit design. It is a new community-based service model highlighting a significant advancement in the degree of collaboration and cocreation in traditional community service models. Additionally, it dramatically demonstrates the potential of socially innovative design thinking in promoting circular fashion and the closed-loop fashion system.

1. Introduction

Fashion, since the industrial revolution in the 18th century, has continued to be one of the industries with a linear economic model [1]. With abundant raw material resources and low-labour costs, apparel companies have repeated this linear process of acquiring, producing, distributing, consuming, and disposing of raw materials, shaping the contemporary fashion landscape into a “take-make-dispose” landscape [2]. While the linear practices have led to growth in urban economies and employment, the continued pursuit of higher profits by apparel companies has resulted in significant resource consumption, environmental pollution, and labour exploitation [3]. Nowadays, more than 80 billion pieces of clothing are produced each year globally, while 80% of them are directly discarded into landfills, causing permanent environmental pollution [4]. In the fifteen years from 2002 to 2017, the arrival of online e-commerce and fast fashion has led to a 70% decline in clothing usage in China [5]. In this sense, the linear fashion model has placed consumers downstream of the value chain [6], creating a consumer culture where people overconsume trendy clothes and discard enormous amounts of fashion products in a short time [7].

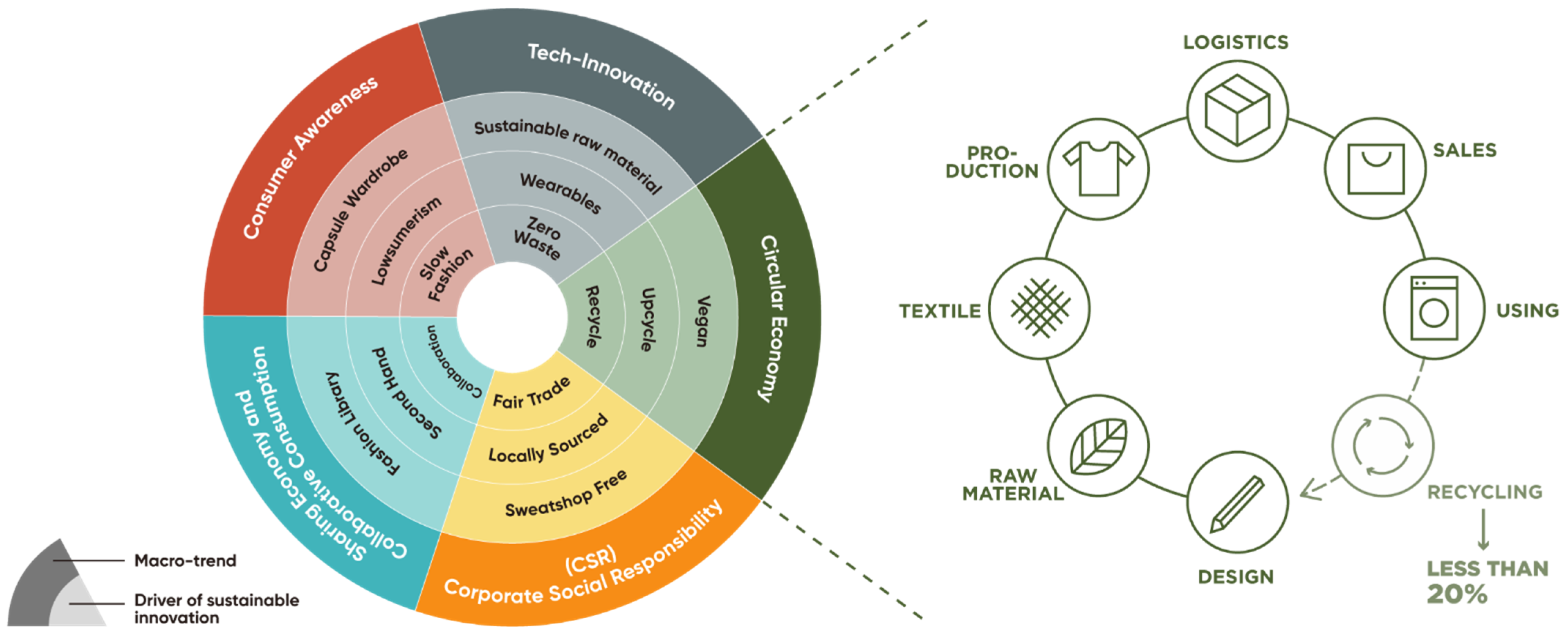

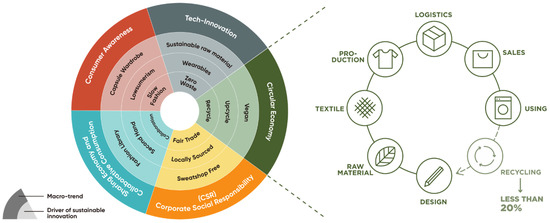

In this context, numerous sustainability trends are driving the transformation of traditional fashion business models, and Todeschini et al. have discovered five macrotrends with diverse drivers of sustainable innovation in their research [8]. Figure 1 shows this synthesizing framework of the five macrotrends [8]. Although these five macrotrends are highly interconnected, “circular economy” has become the most popular trend for both the fashion and design industry, promoting the rising idea of “circular fashion” and extensive design practices. Having recycling and upcycling as its drivers for sustainable innovation, circular fashion emphasizes a closed-loop system of “design, produce, use, and recycle” [9]. Under the global trend of sustainable fashion, the majority of fashion and apparel companies have started to involve clothing reuse and upcycling practices in their business models to reduce the negative environmental impacts and excessive resource use of their brands [10]. However, these practices are still highly limited and contain several issues and barriers to scaling up in China. There are not only technological barriers to the lack of a mature infrastructure and management system for clothing recycling [11], but also cultural barriers in terms of people’s low acceptance of clothing reuse and upcycling [12]. Therefore, in the field of prototype design, this research aims towards the goal of “circular fashion” and starts with a focus on scaling up clothing reuse and upcycling in the context of China.

Figure 1.

Trends and drivers of sustainability-related business model innovation for fashion businesses [8].

The current conditions call for more interventions that can scale up clothing reuse and upcycling from a niche practice [13]. According to research by Kyungeun Sung et al. the main approaches to scaling up are to “provide facilities”, “ensure ability”, and “build understanding” [14], while the community-based interventions are the ones with both high importance and feasibility for these three actions. In other words, the development of community-based, collaborative initiatives has the ability to create enabling environment and provide educational elements, which are highly important for promoting consumer awareness and taking measures toward circular fashion. Therefore, the community-based interventions for clothing reuse and upcycling merit more research and practice design, which is still in lacking in current studies.

Considering this challenge, social innovation frameworks and methods have emerged as noteworthy and promising approaches to innovation and design [15]. When confronted with complex sustainability issues, design for social innovation aims at shaping the paradigm by its problem-solving and sense-making ability, which are two integrated goals that cannot be treated separately [16]. Thus, social innovation design is a promising answer in this research paper, which focuses on community-based initiatives and calls for the interweaving of multiple design roles and collaborative engagement, designing for the local community and with the local community [17] to make things happen in today’s fashion ecosystem. In this context, this paper will try to explore a community-based pathway to scaling up clothing reuse and upcycling under a social innovation perspective.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Clothing Reuse and Upcycling

2.1.1. The Economy Models of Clothing Reuse, and Upcycling

The circular economy framework defines reusing, repairing, reconditioning, and recycling as critical processes to shift the linear model into a circular one (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017) [18], emphasizing the importance of extending the life cycle of resources, residual waste, and other materials as much as possible, and thus creating a closed-loop system [19]. Based on this, Guldmann believes that the prolonged use of raw materials and economic resources lies in the “using” stage of clothing and wasted textiles [20]. According to the hierarchical structure of textile waste, “reusing” is usable discarded clothing being repaired and reworn without any transformation; while “upcycling” is one step after reusing, integrating, upgrading, and recycling into processes that utilize existing objects to create better ones of new usage through different designs and ideas (Kim et al., 2021) [21]. Shen stated his findings in the article Sustainable Fashion Supply Chain: Lessons from H&M that, in general, clothing reuse and upcycling have been considered effective ways to achieve circular fashion. In recent years, clothing reuse and upcycling have started to be widely noticed and practised by fashion brands and apparel companies, including H&M, GAP, Levis, etc. [22].

In terms of clothing reuse, R. Rathinamoorthy, in his study on circular fashion, proposed that the “resale and reuse model” was “the best option to extend the life of the product with the same quality” [1]. Currently, the most widely developed model of clothing reuse is the second-hand fashion business model (Jango et al., 2015) [23], which is usually led by clothing recycling companies that sort discarded clothing and fashion products and sell them to global markets (Machado et al., 2019) [24]. Clothes swapping is another standard model in the field of clothing reuse (Soyer et al., 2021) [25]. It is mainly in the form of temporary or one-off events, gathering people with their used clothes and organizing face-to-face clothing exchange activities. However, compared to the second-hand fashion business model, clothes swapping is initiated mainly by organizations or NGOs based in local communities. The clothes swapping model is practised on a smaller scale and generates almost no profit compared to the second-hand fashion business model (Dissanayake et al., 2022) [2].

Clothing upcycling is a model to convert and remake textile waste or useless clothing into new fashion products when the original state of clothing is difficult to reuse (Park et al., 2020) [26]. Although clothing upcycling requires additional energy compared to reusing, it is also popular among commercial brands as it “eliminates the need for a new product” from raw materials, [27] and it generate new values or meanings for clothing, according to Szaky and Sung [28]. In addition to viewing it as a business model used by some companies, some researchers have pointed out that clothing upcycling is also a production model that belongs to craftsmen and individuals (Sung et al., 2014) [29], some of whom develop businesses in the form of individual workshops. Based on homemade-DIY cultural contexts that have long existed in human society, many individuals pursue an “upcycling lifestyle” that highly reduces daily consumption, aiming towards sustainability (Frank, 2013) [30]. From personal upcycling behaviour and production, individuals would not only gain “sociocultural and psychological benefits”, including a sense of community, learning, and being empowered; but also physical benefits such as getting a small amount of income from providing upcycling services to others and having low expenses by replacing purchasing new things with upcycling actions (Sung et al., 2019) [14].

Clothing reuse and upcycling models are similar in that they both involve repairing original discarded clothing through crafting or other techniques to give new life to used clothing. The difference is that clothing reuse requires only essential repair work, while upcycling requires creative repair, reuse, repurposing, and other upcycling processes that may require various technical skills depending on the condition of the original clothing (Jango et al., 2015) [23].

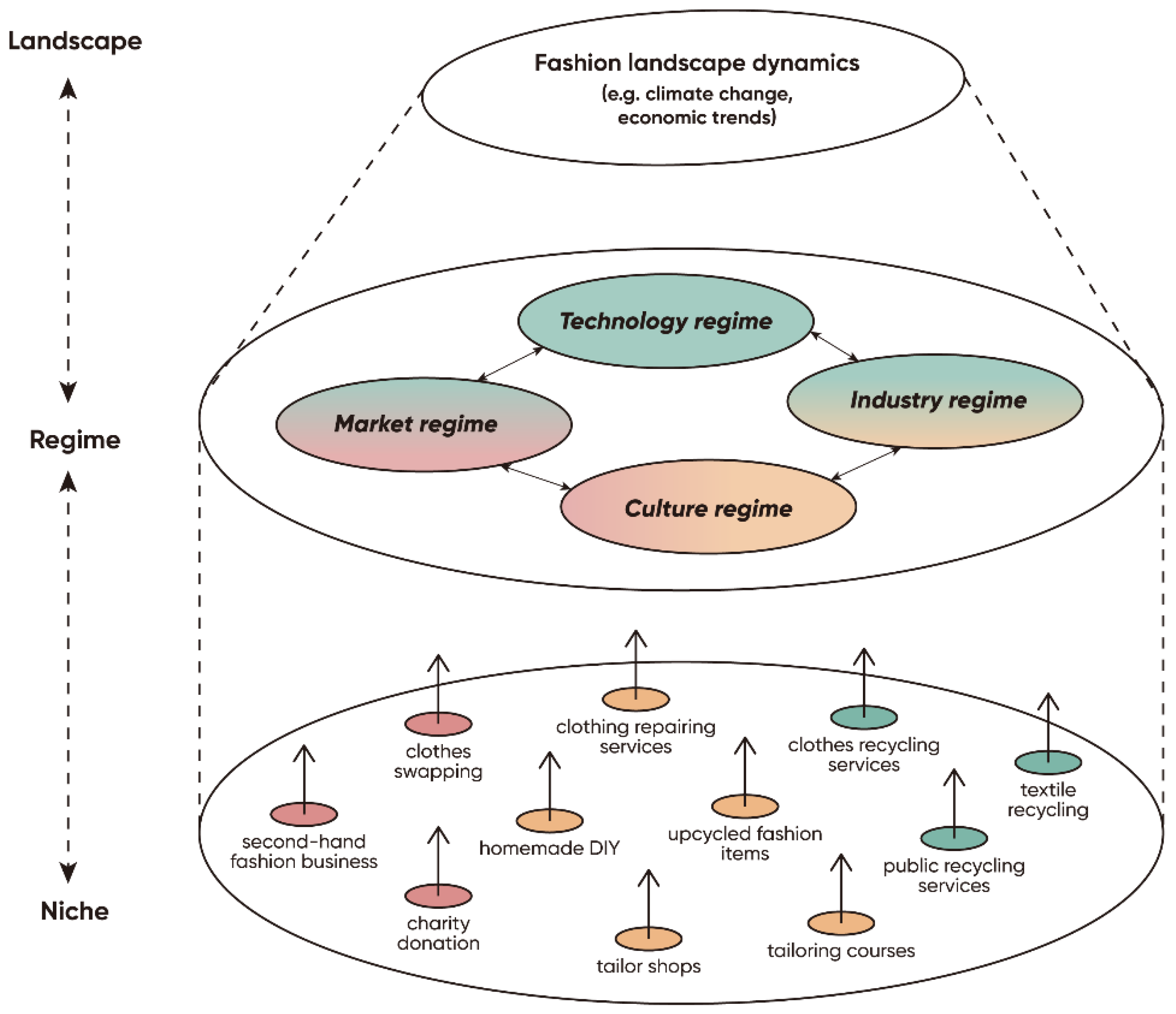

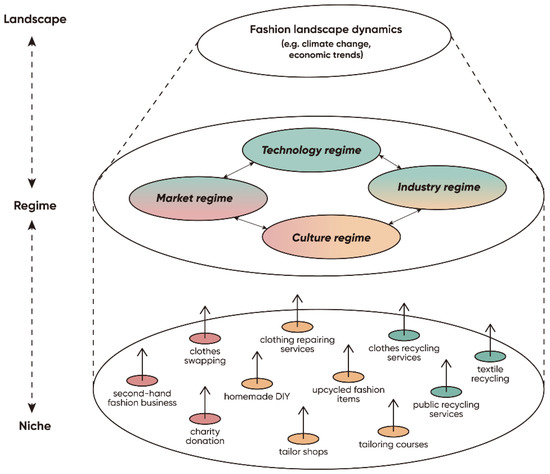

In general, however, these models are both driven by artisanal techniques, neither of which requires large amounts of additional production resources to be consumed. However, each economic model tends to be highly independent and conservative in its original framework with little interaction. Figure 2 shows how these isolated models stay independently in the niche stage [13] and demonstrates how the isolated situation of the niche stage makes it difficult to scale up in our current fashion regime.

Figure 2.

Mapping the current economic models of clothing reuse and upcycling.

2.1.2. The Barriers to Scaling Up Clothing Reuse and Upcycling

Due to the differences in the economic model of clothing reuse and upcycling, the barriers encountered by these two models in the current environment are similar but still need to be discussed separately. This paper summarizes the key issues, barriers and shortcomings of the scaling up of these two models in the Chinese context based on the previous literature.

The second-hand clothing business model has promoted clothing reuse to become a popular concept developed in many countries in the world today. However, in China, clothing reuse is still a relatively marginal and niche business model. Although there is a very diverse range of clothing recycling services offered in China (including Internet-based recycling, brand-led recycling, and government-led recycling), due to the strict laws and regulations on waste management (Frank, C. 2013) [31], only a few of the collected clothes are reused for local second-hand clothing ventures (Xu et al., 2014) [32]. A high percentage of them are exported directly overseas to second-hand clothing markets in other countries or disassembled as textiles for downcycling. This barrier is, firstly, due to a lack of well-managed recycling infrastructure, as the cost of operating and managing clothing recycling facilities is too high to maintain using public services (Guo, 2013) [10]. Xu et al. have pointed out that aside from the technical barriers, there is also a big cultural barrier to the perception of second-hand clothing, where Asian consumers resist wearing clothes worn by others [11]. Especially in China, people have “traditional social hierarchy thinking”, making people highly value their identity and status and hold rigid views towards second-hand items (Xu et al., 2022) [33].

Due to its various technical and craft requirements, the scaling up of clothing upcycling is also confronted with technical barriers. The primary reason stems from the decline of the traditional clothing and garment-making industry. Finnane described the situation in the article Tailors in 1950s Beijing: Private Enterprise, Career Trajectories, and Historical Turning Points in the Early PRC, where, in China, people in today’s society no longer maintain the lifestyle where they look for the best craftsman or tailors in the community to make their daily clothes [34]. As a result, Liu indicated that although this culture of “community tailors” still exists in the daily life of Chinese communities, it has dramatically declined from a profitable market into merely individual actions [35], including DIY and other craft-based activities that are difficult to scale up in the long term.

Regarding the barriers of these two models, the previous study by Sung et al. has emphasized the importance of community-based practices, and “community workshops” ranks as one of the top interventions in terms of both importance and feasibility (Sung et al., 2019) [14], which accordingly are in response to the cultural and technical barriers. The researchers also highlight the importance of developing “local networks of passionate hobbyists and activists for upcycling and associated activities”, which aims to promote changes in people’s intentions, attitudes, and subjective norms in their daily lives.

Participatory design is an appropriate method to tackle challenges of sustainable fields. The core characteristics of sustainable issues are the need to reconfigure, realign, and renegotiate diverging and heterogeneous interests in many application domains and at several levels of scale. Participatory design is well-equipped to solve these problems (Hakken et al., 2014) [36].

The principles and approaches of participatory design can help nurture more transparent and inclusive tools, and can also balance the needs, habits, understanding, and other nuances of all parties. This will make technology and design more acceptable (Davis, 2012) [37]. People can learn skills and expertise from each other and gain the sense of ownership, attachment, commitment, and empathy by being involved in participatory design practices, as long as they strive towards the success and consolidation of their endeavours. Therefore, when participatory design practice is actively used in specific scenarios its outputs, which are more extensible, tailorable, and maintainable, and the changes, encouragement, and opportunities it brings to all the participants can improve the sustainability of projects.

In addition, participatory design also has a unique way of understanding and handling culture. Poderi and Dittrich believe that “really existing” cultures are more accurately conceived of as a salad of analytic shreds and patches than a coherent totality. Therefore, we can study them step by step, by first focusing on one relevant aspect of culture at a time, and then examining sequentially other cultural forms, and finally assembling these specific accounts into a narrative that also reflects the actual degree of cultural coherence manifested in the question [38].

However, there is a lack of previous research on community-based scaled up clothing reuse and upcycling design. Furthermore, prior research has not yet paid adequate attention to the public interest in upcycling, such as upcycling-based crafts and homemade DIY, or on comprehending upcycling at a household level as individual behaviour, despite both being highly relevant to scaling up clothing reuse and upcycling and community-based sustainable fashion practices.

2.2. Design for Social Innovation

With the full development of social-technical society in the 21st century, we are facing more and more complex systemic and sustainability issues in the new civilized world. Many studies, led by Ezio Manzini, have focused on the topic of social innovation, emphasizing its importance for coping with social problems (van Wijk et al., 2019) [39], promoting social change and social well-being (Manzini, 2007) [40], and guiding society toward sustainable development (Schaltegger et al., 2008) [41]. In design for social innovation (DfSI), the main emphasis has been on “the role played by people and communities in creating change within their own local environment and circumstances” (Gaziulusoy et al., 2021) [42]. In recent years, the focus has been on investigating how the process of replication and scaling up can be facilitated by expert designs (Manzini and Rizzo, 2011) [43]. In this context, this paper views DfSI as a potential perspective for scaling up clothing reuse and upcycling. It also establishes a research framework through a review of the design mode map defined by Ezio Manzini to develop a working hypothesis for this research.

The meaning of design in the context of social innovation and the design paradigm is very different from our traditional perspective of expert design or professionally trained design. Meroni supposed that the socially relevant issues we face today are often highly complex, dynamic, and local, and the social innovation supporters who are the first to recognize these complex issues and try to drive social change come from ordinary people and communities [17] who are mostly the owners of the problems they are addressing, and act on a “bottom-up and self-organized basis” (Gaziulusoy et al., 2021) [42]. These people solve problems through natural, untrained inventiveness and creativity, which, in Manzini’s research, is a design activity, an ability that we all have [16].

In this sense, this paper uses the design mode map (see Figure 3), with four “typical” design modes identified by Manzini, as a benchmark for understanding the many design activities that are taking place in the context of social innovation. This map demonstrates that the emergence of social innovation actions and practices often requires that these two pairs of traditional opposites converge in two dimensions and move closer and closer to the centre of the map. In the horizontal dimension, the unification of problem-solving and sense-making facilitates the emergence of an “emerging design culture.” In contrast, in the vertical dimension, diffuse design and expert design form a synergistic new organizational form, the “design alliance”, to solve everyday problems. According to the research of Chick, in this open, collaborative design process, expert design is no longer decisive in dictating problem-solving, but is in a fundamental and specific position to create a more enabling environment for design alliances as an agent that can be triggered to sustain and guide the processes of social change towards sustainability [44].

Figure 3.

A design mode map for social innovation [16].

3. Research Framework and Hypotheses

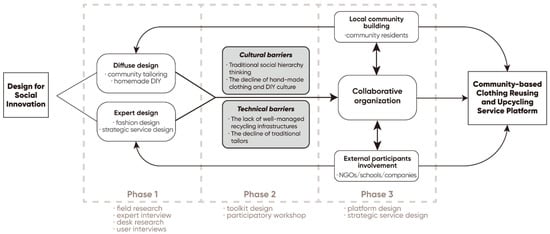

Based on a literature review of “Clothing Reusing and Upcycling” and “Design for Social Innovation”, this paper finds that clothing reuse and upcycling urgently needs scaling up to promote environmental and social sustainability in the fashion industry, however, scaling up faces many technical and cultural barriers.

The research therefore takes a social innovation perspective to conduct design studies which focus on the convergence of “four types of design modes” shown in Figure 3.

The hypothesis is to create a design framework to help with the technical (problem-solving) and cultural (sense-making) barriers that clothing reuse and upcycling face. Further on, it establishes a platform proposal which combines strategic service design and practical toolkit design. The new community-based service model will promote the collaboration and cocreation in traditional communities and demonstrates the potential of socially innovative design thinking in promoting circular fashion and the closed-loop fashion system.

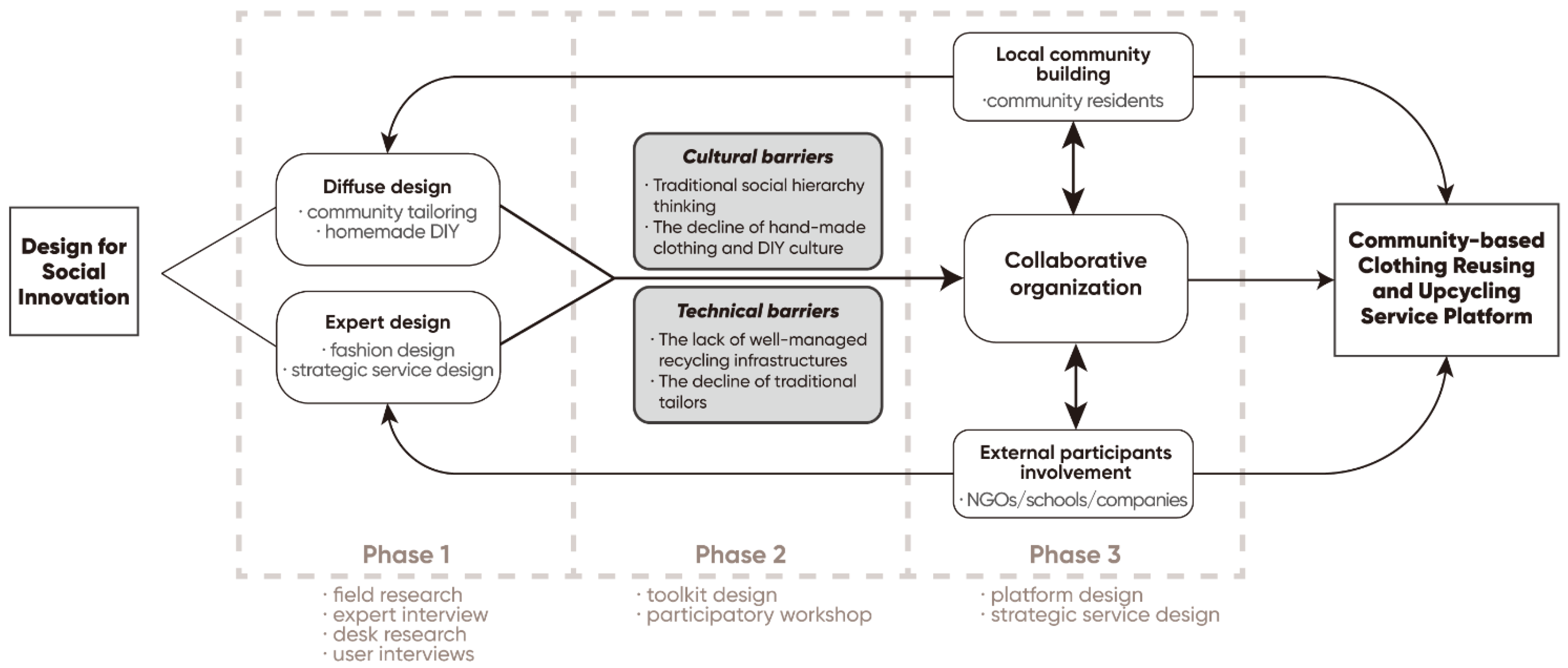

Figure 4 shows the research framework of this study, using social innovation design as the working methodology, and explores three design phases of community-based scaling up of clothing reuse and upcycling through primary and secondary research.

Figure 4.

Research framework.

4. Research Process and Methods

Based on the research questions and the literature, this paper explored the design and enabling solutions for building a collaborative platform with the objective of scaling up clothing reuse and upcycling services. The research focused on the main supporters of this collaborative organization, namely the potential service providers and receivers. At the same time, due to the robust localization of social innovation issues, this paper selected the research participants based on Shanghai residential communities. Additionally, based on the research questions, this study did not differentiate or restrict the age or gender of the participants.

4.1. Phase 1: Participants’ Research

4.1.1. Research on Local Tailors

Most tailors in Shanghai are divided into community tailors (or street tailors who are more traditionally “old ones”), and “new tailors” who are more diversified in their business response to the development of the Internet [45]. Since most of the “old tailors” manage their daily work in community environments, while most of the “new tailors” work through online platforms, this research selected representatives of the local “old tailors” and conducted field research and expert interviews.

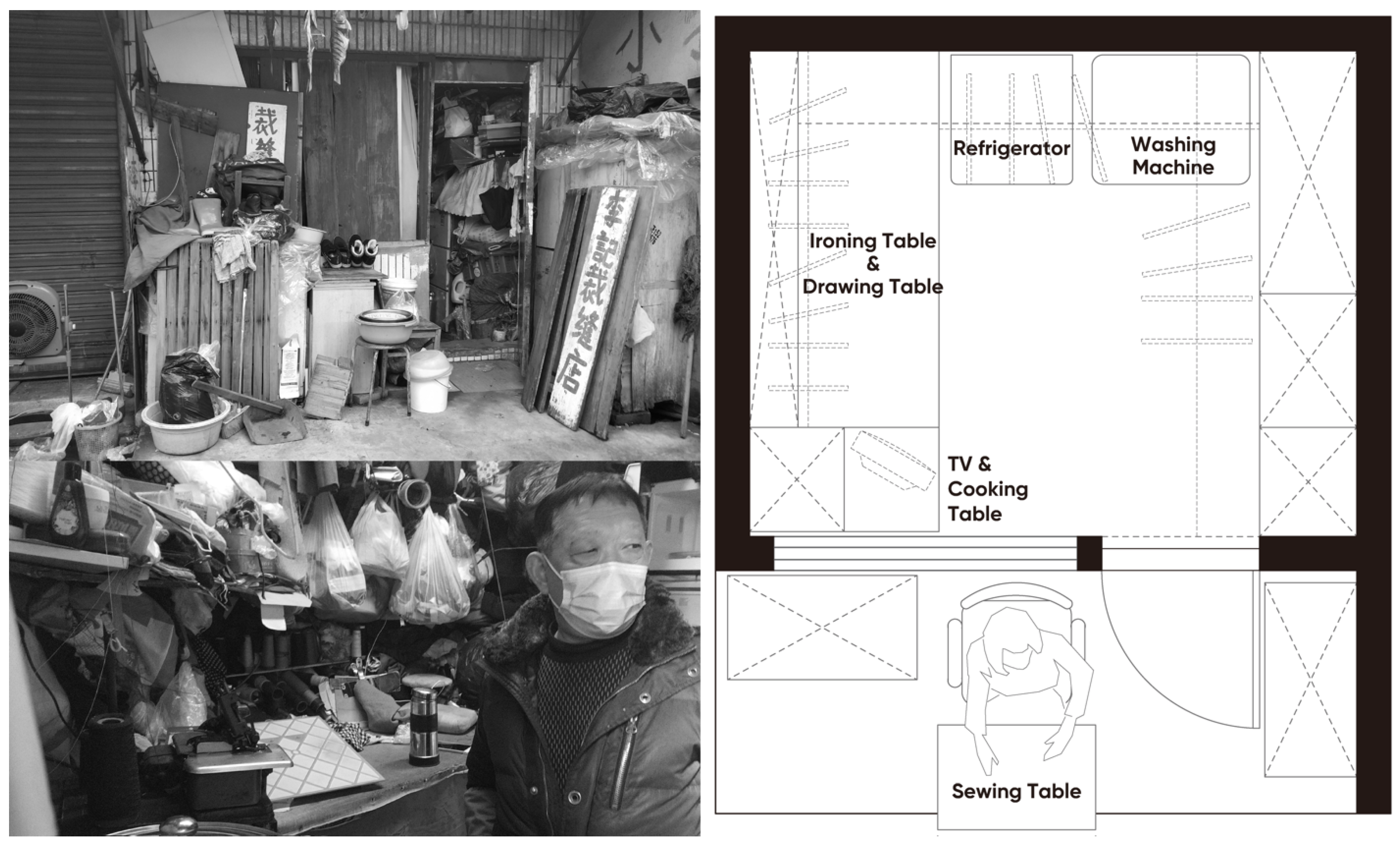

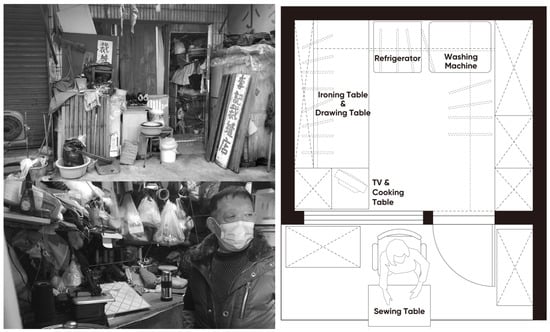

Field research was conducted to understand the traditional “old tailor”, and Mr. Li, a tailor located in the Sitang community of the Baoshan District, Shanghai, was selected for this study. Li was born in the 1960s, a native of Jiangsu province, and had been in the tailoring business for 38 years. He learned tailoring skills in 1982 (the early stage of the reform and opening up) and has moved around the world to complete tailoring work. The tailor’s store, Li Ji Tailor Shop, is located in the Xinxing Market in the Sitang community and has been operated by Li Ji since 2000. The store occupied a small and crowded space of about 5 square meters and was difficult to be found by passersby. Although Li stored all the necessary tools, accessories, and materials for his work, as well as the electrical appliances he needed for his daily life, the space was so small that he had to use the public space outside the store for his sewing machine (see Figure 5). In the past, Li has had to use a tricycle to carry his sewing machine to the streets to solicit business due to poor business, but this kind of mobile work was no longer possible due to the heavy workload and regulations.

Figure 5.

Photos and drawings of Li’s tailor shop space.

Most of Li’s customers came from the surrounding community, both young and old, with a large number of older (middle-aged and old-aged) customers, and occasionally old customers drove there after moving. Around 80%–90% of Li’s daily business was for alteration and repair services; customization services were less common and were generally for elderly people with particular figures, and occasionally for young women’s trendy coats. However, because the tailoring business was not ideal, the income from tailoring work alone could not sustain Li’s daily needs. He worked on tailoring during the day (7:00–18:00) or took a nap when there was no work, and after closing the shop at night, he went to the surrounding community to work on security duty to receive daily income for subsidies. At the same time, due to the rapid decline in the number of people learning the tailoring craftsman, Li had not been able to find suitable disciples to pass on his craft and work, so he believed that if his business continued to decline, in five years he would close his shop and retire.

4.1.2. Research on Community Residents

Regarding community residents, who are the key players that use and handle clothes in the living communities, desk research was conducted first to understand how they recognized clothing reuse and upcycling in their daily lives. Based on the secondary research, the paper further researched and collected information from community residents through user interviews and participatory workshops, which aimed at understanding how they perceived tailors as part of their communities and whether they were able to shift from the traditional “being served” model to the “co-management/production” model of collaborative organizations.

- Desk Research

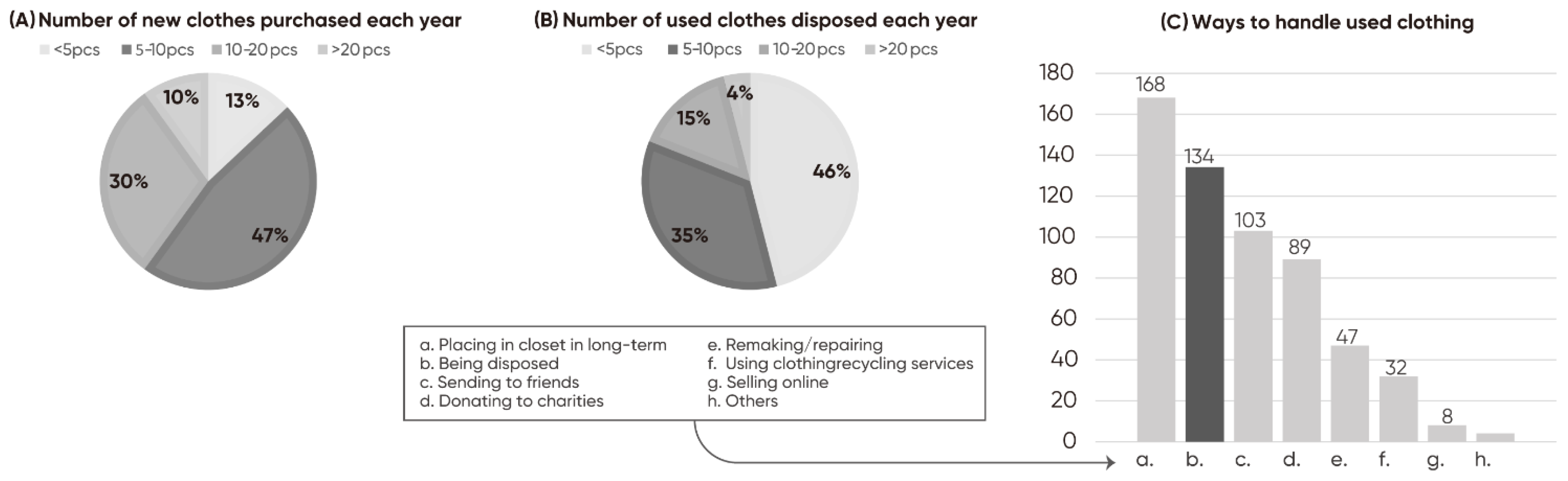

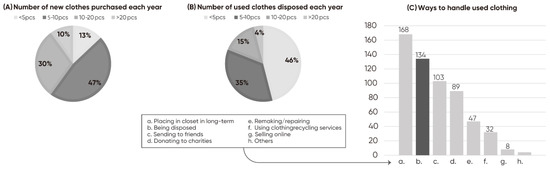

In this paper, we searched and organized the research literature and reports related to clothing reuse and upcycling in the context of Shanghai, and the main results were concentrated in the article Research on Current Situation of Recycling Unwanted Clothes in Shanghai by Liu et al. [46]. Through the field research of 278 local residents, it was found that interviewees mentioned 168 times that they “keep used clothes in their closets for a long time” and even 134 times that they “throw away used clothes directly.” In contrast, they mentioned “handing over used clothes to clothing recycling organizations” only 32 times and “reusing used clothes after transformation” was mentioned only 47 times.

This second-hand data showed that the majority of Shanghai residents still took a more negative and passive approach to recycling clothes, such as placing them in the closet or disposing directly, while only a few people took more positive approaches, such as recycling and remaking (see Figure 6). Although 225 of the 278 interviewees agreed that clothing recycling is an excellent way to reuse resources, and 155 of them believed that it could reduce pollution, the data revealed a massive gap between their awareness and actual actions or behaviours. Moreover, the majority of interviewees believed that they had seldom or essentially never heard about clothing recycling or reusing. It was evident that Shanghai residents purchased new clothes frequently and even purchased more than they needed, but they were completely unfamiliar with the proper disposal of clothes after using them in their daily lives.

Figure 6.

Clothing purchasing and disposing trends of 278 interviewees [46].

- B.

- User Interview

Based on the desk research and the second-hand data collected, this paper thus needed first-hand data to better understand the needs and value preferences of the community residents under the scenario of clothing reuse and upcycling in Shanghai communities. Therefore, this paper found eight Shanghai residents from online recruitment through the authors’ social media channels for a user interview. The eight interviewees were selected based on three criteria: (1) the number of years as a Shanghai resident; (2) the familiarity with clothing reuse and upcycling; (3) the user experience of tailoring services. The selected informants happened to show varying degrees of the three criteria and thus could reflect different user profiles of Shanghai residents to the greatest extent possible. The interviews were conducted through the online meeting platform Zoom and were based on a semistructured set of questions in 30–40 min (see Appendix A). All the answers to the questions were transcribed into first-hand data, which were finally grouped and coded in two major areas of “clothing reusing and upcycling” and “tailoring services.”

In terms of “clothing reusing and upcycling”, Ms. Wang, a 35-year-old white-collar worker living in Shanghai, said that she “just threw away her torn clothes” and “there were no recycling bins in prime locations.” The 21-year-old college student, Shi, tried “as far as possible to give the old clothes to neighbours and community cleaners”, while his “cotton sweaters could only be thrown away.” The 23-year-old student, Wang, mentioned “recycling was very inconvenient” and recycling might “require a large cost investment.” The 47-year-old white-collar worker, Ms. Li, was the only user who had tried to “reuse old clothes” in her daily life, but most of them were used clothing downgraded to rags or mops for housework. She said that even if she had considered making something new, she did not have “a sewing machine for delicate works.”

The interviewees showed very different views on “tailoring services”, among which there were three representative ones: Shi said he often visited the “tailoring stall” at the intersection of his living community since his father used to have his shirts repaired there and he did not know how to repair them himself. So he had to ask the “old tailors” to help as there was no one else to alter his shirts. Ms. Wang, the white-collar worker, often visited the community tailor shop in her neighbourhood, and thought that community tailors were very convenient, and that if we did not have them anymore, it would increase the cost of living. However, she did not think that community tailors could repair anything other than alter trouser legs.

4.1.3. Results Analysis

The field research on the traditional “old tailors”, who were mostly self-employed, showed that these community tailors had the advantages of affordable prices, convenient locations near the community, excellent craftsmanship, and trust from the community. These advantages demonstrated that community tailors not only had the essential capabilities for providing clothing reuse and upcycling services, but more importantly, they were one of the key elements and connections that built up the community culture. However, they were highly limited by their personal financial ability to provide a better image and environment for their own services. Additionally, since these “old tailors” had not kept up-to-date with modern trends, it was difficult for them to broaden the range of services they could offer alone, resulting in a deficiency in their daily work and a poor revenue status. Thus, these community “old tailors” were in need of help to encourage their potential to act as service providers who could help with the technical and cultural barriers that clothing reuse and upcycling face. In other words, they needed to regain their “community tailor” identities in a new way that could lead to a “new tailoring service” development and the repopularisation of “tailoring culture.”

For community residents, the research and interviews showed that there was a big difference between users’ awareness and behaviour. This was not only due to a lack of basic knowledge of clothing recycling, repairing, reusing, and upcycling, but also due to the incredible lack of guidance in the community environment, where residents had no supporting infrastructure even if they had the intention of reusing and upcycling their clothes. At the same time, the interview showed that local residents in Shanghai did share the culture and memories of “community tailors” and DIY from the old times. Even if they had different preferences in their daily clothing and tailoring services, they still regarded the culture as part of their local lives. Based on the data from the interviews and from previous desk research, the authors thus grouped the converging traits, needs, and value preferences the residents possessed, and developed four typical types of user profiles (see Table 1). The “Modern Users” valued their experiences and were willing to invest in high quality, and thus were more optimistic about disposing and recycling their used clothes. The “Conservative Users” needed a more diverse and practical appeal, and they were influenced by family (or friends) around them for changes in their clothing consumption behaviour. Additionally, they did care about the actual financial input and return. The “Pragmatic Users” mostly had craft-based hobbies. They needed better guidance for clothing reuse and upcycling and were more likely to quickly change to find joy and (especially after retirement) meaning in their daily lives. The “Fashionable Users” had a vibrant subcultural community, creative and self-expressive, and would change with the influence and help of their environment, but they needed better customization and convenience of the services.

Table 1.

Four types of user profiles for clothing reuse and upcycling.

The four typical user profiles provided a clear group portrait of Shanghai residents, showing the importance of the target and potential users to have the services in a situation that could be convenient, accessible, cost-effective, and trustworthy. These user profiles would be the criteria guiding the following design phase and helping the initial design conceptualization.

4.2. Phase 2: Design Prototyping

4.2.1. Toolkit Design

Based on the previous conclusions, the toolkit design proposed to establish both physical tools and digital tools, which were correspondingly the “physical spaces to give participants the chance to meet and work” and “digital platforms to connect people and to make self-organization easier and more effective” in the infrastructure elements [47]. For the physical tools, two different concepts can be adapted to different conditions of community spaces to provide the necessary infrastructure, which are the “Upcycling Case” and the “Upcycling Bike.” For the digital tools, an integrated online service platform was proposed to facilitate online connections in the community.

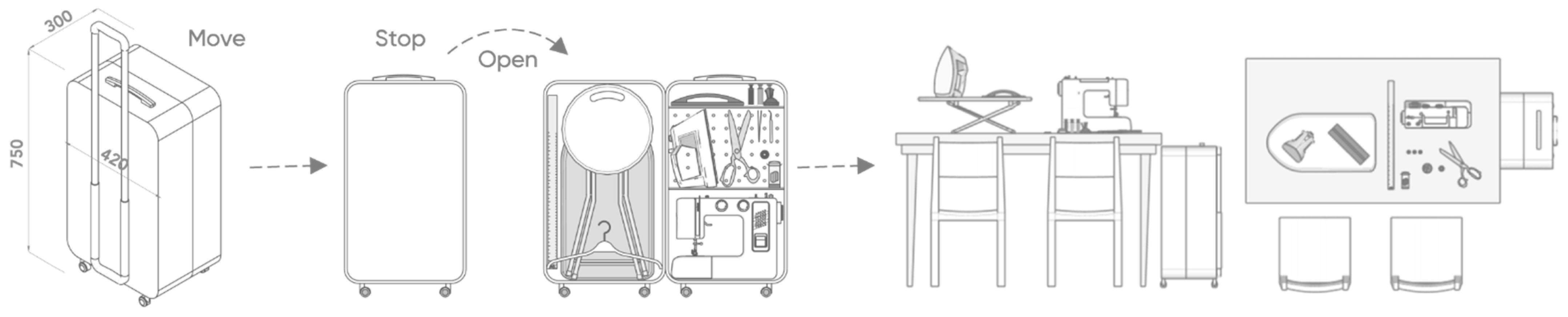

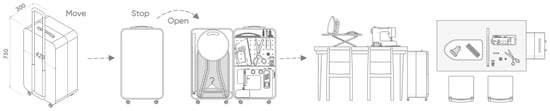

- The “Upcycling Case”

For the situations where services need to be carried out a relatively long distance from the community the “Upcycling Case” is a highly storable and portable tool that can be carried by a working group and adapted to all spatial conditions. The “Upcycling Case” is modified in the form of a trolley case to ensure maximum mobility and portability. In a case, 420 mm wide, 750 mm high and 300 mm deep, the “Upcycling Case” can accommodate a folding chair, a small ironing table, a sewing machine, an iron and other necessary equipment such as needles, thread, and scissors, and other materials can be added and transformed according to the actual needs (see Figure 7). The overall net weight of the case is about 15 kg, and it thus can be moved horizontally with the help of the tow bar. Carrying and protecting all the equipment, the case enables the working group to stop and work on the move whenever and wherever they want. When opened, the “Upcycling Case” can be unfolded with the assistance of a regular tabletop to assist in the placement of the sewing machine and ironing table, thus enabling the worker to perform basic tailoring tasks such as measuring, cutting, sewing, and ironing.

Figure 7.

Drawings of the “Upcycling Case”.

- B.

- The “Upcycling Bike”

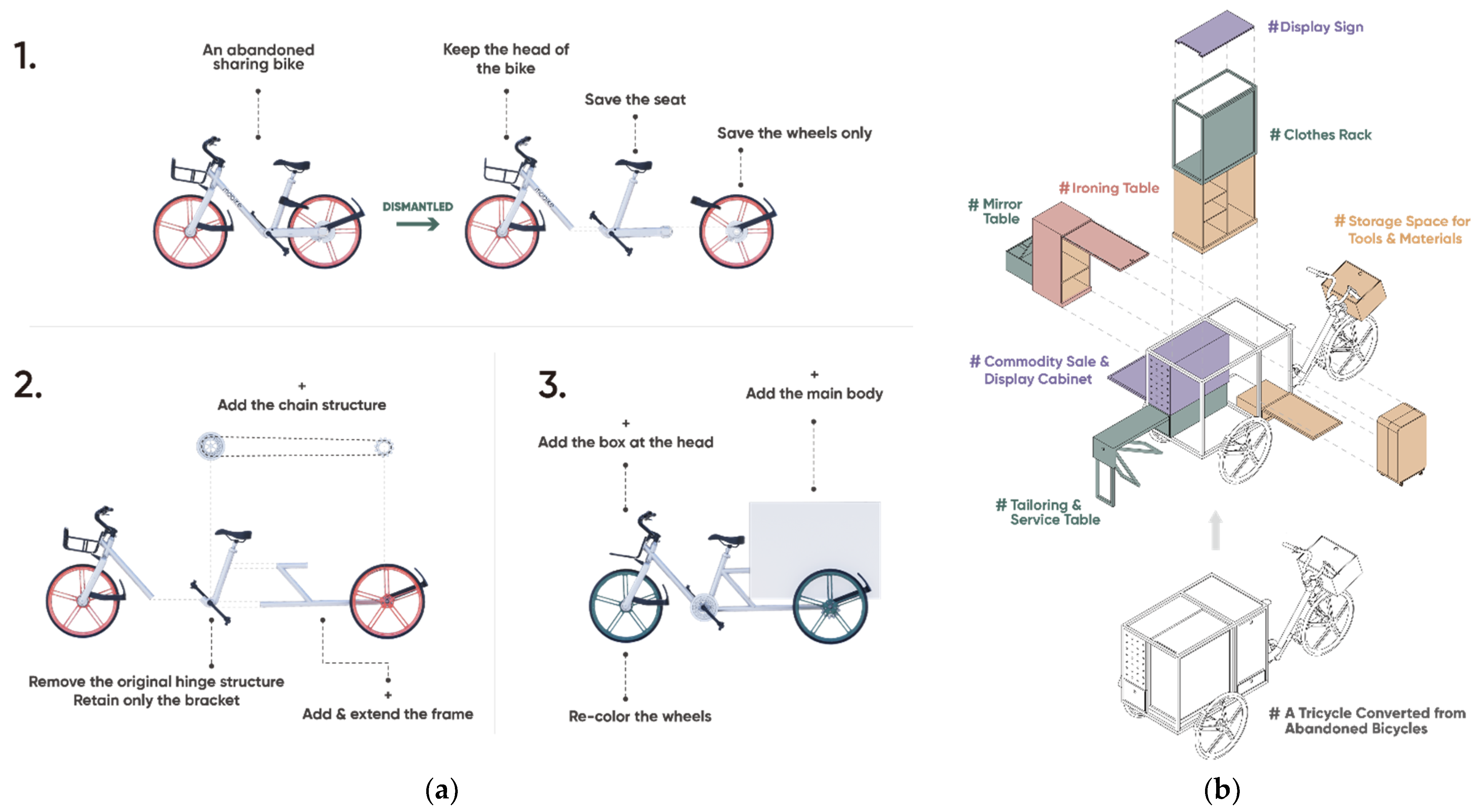

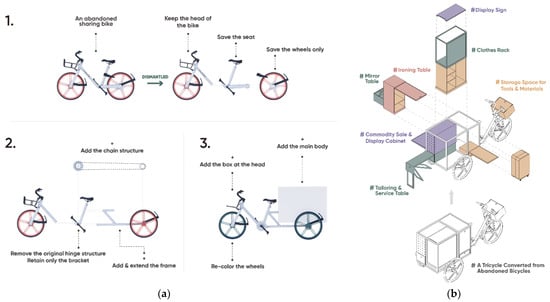

For outdoor public spaces and indoor community spaces, inspired by the traditional tailor’s tricycle, the “Upcycling Bike” provides a mobile yet reliable tool to store a wider variety of complex equipment while being able to be transformed and unfolded to accommodate scenarios such as a pop up exhibition and clothing stores. The “Upcycling Bike” model is derived from traditional tricycles and considers the mobility and higher manoeuvrability of a working group in the local community. Therefore, combined with the concept of upcycling, old raw bikes can be recycled and retrofitted from shared bikes that have otherwise been abandoned in large numbers (see Figure 8). Since abandoned shared bicycles often have their main bodies still in good condition, mostly when components such as smart locks and chains fail, the overall body of the shared bicycle is extended to accommodate the main box for storing tools and equipment while retaining the main body of the bicycle.

Figure 8.

(a) Drawings of the “Upcycling Bike”; (b) Functional modules of the “Upcycling Bike”.

The main functions of the “Upcycling Bike” are divided into four categories: the repairing service module, the ironing module, the display and sales module, and other storage modules. All these modules need to be relatively easy for all workers to operate and move around. Therefore, to enable the opening and closing of the space, the “Upcycling Bike” chooses to operate by sliding, flipping, and pulling in clear and easy directions (see Figure 9). Thus, the carriage is more stable and less prone to collision during movement and more clearly guided by the interface when working at rest.

Figure 9.

Three clothing upcycling workshops in Siping and Huaihai communities.

4.2.2. Participatory Workshops

Based on the aforementioned desktop research and user research, the research team conducted three participatory workshops on the theme of clothing reuse and upcycling (see Figure 9) among communities in Yangpu and Huangpu districts in Shanghai (the prototyping area).

The workshop participants consisted of the following roles:

- -

- Expert: local community tailor and designer

- -

- Assistants: researcher, community staff, or residents with some sewing skills

- -

- Facilitators: researchers

- -

- Participants: community residents

- -

- Coordinator: community staff

Each of the workshops had a combination of one expert, three assistants, two facilitators, 15–20 participants and one coordinator. Both the participants and the assistants were self-registered from the community. Workshops one and two were located in high-density residential communities in the Yangpu District, and workshop three was conducted in a more commercial community in the Huangpu District (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Detailed information from the three workshops.

In the first phase of the workshop, the facilitators spent 10 min giving a basic background introduction to help the raise the participants’ awareness of sustainable fashion. This was followed by a 10 min exercise where all participants were asked to share three clothing recycle and reuse cases that they had tried or heard of to ensure an explicit understanding of the workshop theme.

In the second part, participants learned some basic skills through small tasks. After a very basic sewing technique introduction, each participant was able to learn how tools could help in the process and gain the confidence to accomplish the codesign ideas. Then they needed to finish a small task which required them to use waste fabrics to make a badge and introduce it. This phase of combined hands-on practice with a self-introduction and warm-up took 30 min.

Afterwards, the third part was designed to encourage the participants to be engaged in the real cocreation task of clothes upcycling. They were guided through the process of a given theme upcycling task “step-by-step” (the three workshops conducted different cocreation themes), and with the help of the “expert and assistants”, all of them were able to finish their unique creation in 60 min.

The final exhibition session was designed to emphasize a sense of fulfilment. Each participant became a model to show their creation and they took an exhibition photo together.

These exercises were conducted in similar-sized spaces among different communities. This workshop set-up was arranged to produce several types of data. The documentation methods involved continuous video recording which covered most interactions taking place in the settings and photos taken by the coordinator throughout the activities.

At the same time, each of the facilitators made fieldnotes to record their observations of the dynamics between participants and their reactions to the processes, materials, and outcomes. After the workshop, the facilitators also collected participants’ comments through emails and phone calls to record short-term (within 7 days of the workshop) and long-term (after one month) feedback.

Throughout the workshops, participants were observed to be highly interactive and collaborative. This was demonstrated by the “expert and assistants” actively offering helpful skills in practising small tasks. The community members actively engaged in the process, in addition, the participants actively shared their experiences and opinions about clothing reuse and upcycling while completing the tasks. They also build a sense of belonging to the community and gaining a great variety of knowledge and information through interaction with other residents, hobbyists, and professional tailors. The community staff also expressed their support for such a participatory and collaborative activity during the workshops.

4.2.3. Results Analysis

Using the experience of the three workshops as evidence, all the participants showed a high level of collaboration and gave feedback of feeling a higher sense belonging to the community culture. The long-term feedback from participants showed that 80% of them (from workshop one, two, and three) shared the clothing upcycling recreational experience with their friends, and about 45–50% of the participants from workshop one and two practiced again afterwards. The second number in workshop three was lower at 25% mostly because of the lower component of retirees and DIY hobbyists as participants.

Furthermore, some of the residents with no prior skills have developed into community DIY hobbyists and could work as assistants at the later workshops we organized. It showed that the recycling and upcycling community has the potential to self-grow as the community ecosystem is established.

In conclusion, the three-phase prototype practice did demonstrate that traditional tailors had the technical ability to address the reuse of clothing but were hampered by cultural barriers that prevented further development. At the same time, community residents showed awareness of clothing reuse, and different types of users all had value preferences in their ability to be involved in sustainable fashion activities especially those who had more interest or disposable time. However, the current community services and infrastructure did not meet their needs for clothing reuse and upcycling services. In addition, community residents, hobbyists, and tailors showed a high level of collaboration in participatory workshops and a desire to form sustainable cultural communities. Therefore, this paper argued that, under the social innovation perspective, community-based clothing reuse and upcycling services which involve and connect community residents, hobbyists, and tailors could be an efficient enabling solution helping break down the barriers of scaling up. Such community-based services then need to have infrastructure that support their cooperation and comanagement and should also be able to adapt to different conditions, including:

- Be close to the community in which they live, have easily accessible recycled or reclaimed for clothing and be easily understood by community residents of all ages.

- A service of a certain quality that allows users to have a pleasant, hands-on experience at an affordable price and promotes more proactive activities.

- The autonomy of universal participation, which can help a portion of users who wish to join, to personalize the expression of their clothing regeneration while further helping them to practice.

- The formation of a community of learning exchange that can facilitate interaction and help further the spread of sustainable culture.

4.3. Phase 3: Developing Community-Based Clothing Reuse and Upcycling Services

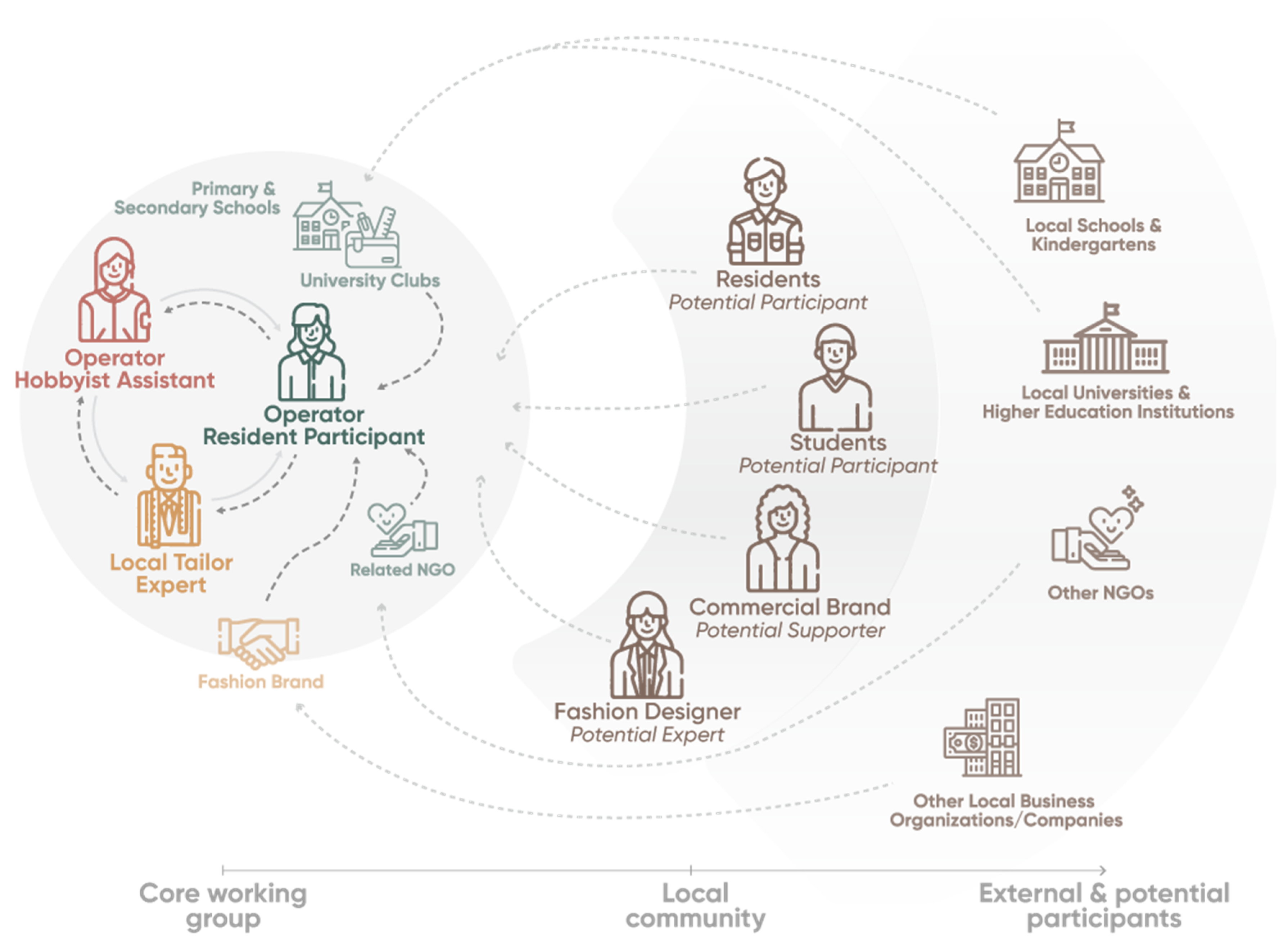

4.3.1. The Community-Based Service Network

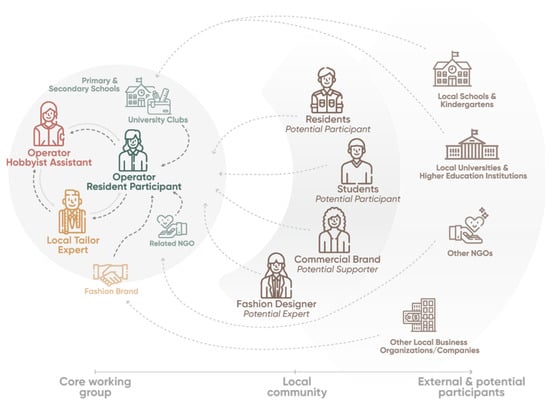

Based on previous research and analysis, this paper has discussed how to develop community-based clothing reuse and upcycling services and the need for an overarching strategic design. Following the concept of “networked governance” [48], this research thus proposes the “community-based service network” in the hope of solving many existing problems in the community while better meeting the current unmet needs of users and forming a creative community culture. The network should connect local residents and hobbyists with community tailors to form a core working group in which participants comanage the services and coproduce the reused and upcycled clothing. At the same time, with further connections with local community schools, fashion brands, and other NGOs, this network could be expanded and enhanced through collaborated classes and events (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The community-based clothing reuse and upcycling services network.

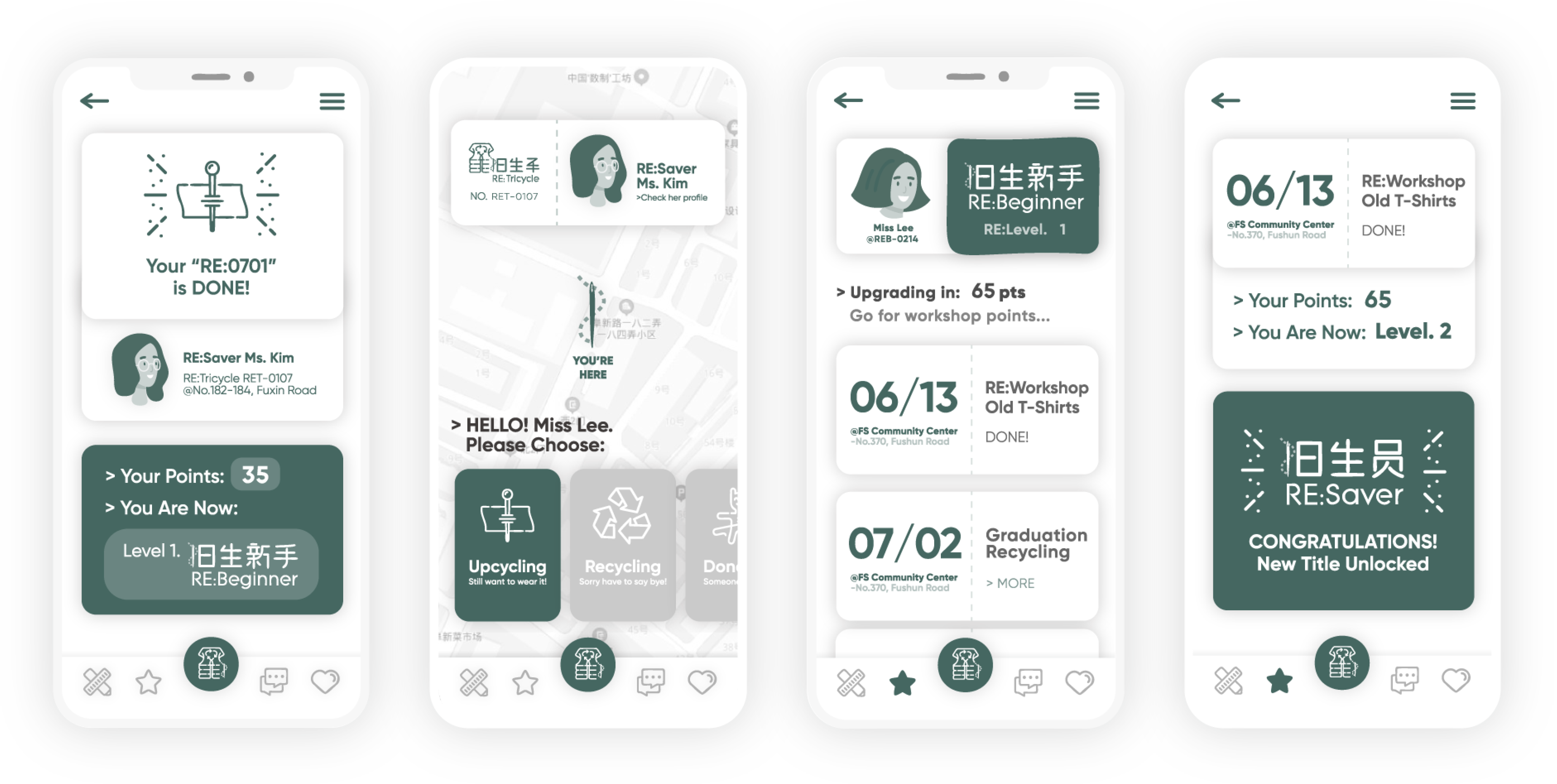

4.3.2. Developing the Online Platform

According to the physical tools, the online platform could mainly include the core module of “clothing upcycling service reservation”, “individual courses and activities”, and “learning and exchange forum” modules. In the core “clothing upcycling service reservation” module, users could locate and select the service from the nearby site through the online platform when they are close to the “Upcycling Case” or “Upcycling Bike” offline (see Figure 11). After submitting the service needs and clothing information, the platform would directly make a “clothing evaluation” of the clothes to let the users know the sustainability of the clothes they choose in terms of material selection, production process, transportation process, etc. The more sustainable the clothes are, the higher the points would be. These points can be directly redeemed for used-life services and will be recorded in the user’s personal profile to encourage users to choose more reusing and upcycling services and become engaged in a transparent closed-loop clothing system.

Figure 11.

Digital interfaces of the online platform.

4.3.3. Service Network Effect

Having an “Upcycling Case” and “Upcycling Bike” as infrastructure that facilitate the community-based clothing reuse and upcycling services network, this platform shows a collaborative pathway towards strategic service design for circular fashion. this service network is an “enabling solution” [16] and creates a collaborative community, where the intensity of individual input is reduced, and the benefits people receive from participating in the organization and becoming cocreators are increased. The reduced individual input not only includes a reduction in the cost of time and learning that users invest, but also means that tailors and hobbyists are fully supported with the skills and resources they need to develop their work. At the same time, the increased benefits lead to a creative community as well as a cultural community for cocreation. In this sense, more people and actions would be encouraged and involved in this service network, promoting the separated clothing reuse and upcycling practices to be connected and scaled up in the local community.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This paper defines the critical role of clothing reuse and upcycling in driving circular fashion and identifies its biggest developmental issue: scaling up from the niche stage to the current fashion regime. Through a systematic literature study and review, this paper argues that the key to clothing reuse and upcycling lies in breaking down its technical and cultural barriers and maintaining a strong relationship between them. Through a review of the literature on design for social innovation, this paper suggests for the first time that the ability of design for social innovation to problem-solving and sense-making overlaps highly with the technical and cultural barriers to scaling up clothing reuse and upcycling. Thus, this study fills the current design research gap for clothing reuse and upcycling under a social innovation perspective.

Moreover, this research was conducted in the context of the Shanghai community, and a large amount of first-hand research data were obtained through field research, expert and user interviews, and participatory workshops. This helps not only existing research to obtain more research information and evidence on clothing reuse and upcycling but also helps subsequent design research to obtain supporting practical information.

Finally, this article analyses the research data and establishes a proposal for a service design network developed from strategic service design to a practical tool design. This is a new community-based service model for existing research, highlighting a significant advancement in the degree of collaboration in traditional service models. It also dramatically demonstrates the potential of socially innovative designs, rather than traditional industrial designs, in promoting circular fashion and a closed-loop fashion system perspective.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

The main part of the research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, thus more in-depth user and expert interviews could not be achieved, which could lead to limitations for obtaining complete research information on the local tailors and residents. Additionally, due to the design prototyping process, all the design proposals in this paper are still at the virtual design concept stage and need to be further developed and iterated into physical prototypes. At the same time, the service network design proposal in this paper is still in the preparation process and has not yet been fully implemented.

Future research should continue to focus on the effectiveness of the service network. Furthermore, experiments should be conducted based on other regional cultural contexts, which could test the wide potential of the design for social innovation to promote clothing reuse and upcycling in different countries or regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.W., M.Z. and Y.Z.; methodology, D.W. and M.Z.; software, X.Z.; validation, D.W. and X.Z.; formal analysis, M.Z.; investigation, M.Z.; resources, X.Z.; data curation, D.W.; writing—original draft preparation, D.W.; writing—review and editing, D.W. and X.Z.; visualization, M.Z.; supervision, D.W.; project administration, D.W.; funding acquisition, D.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Siping and Huaihai communities for supporting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Profiles of selected interviewees.

Table A1.

Profiles of selected interviewees.

| Number /Name | Residence in Shanghai | Occupation | How Much Do You Know about Clothing Reuse and Upcycling? (Rate 1–5) | Do You Know Your Community Tailors Well? (Rate 1–5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-Mr. Fu | 4 years | Student | 4: Knows about it and has tried several times before | 1: Definitely not |

| B-Ms. Li | 35 years | Accountant | 1: Never heard of it | 2: Probably not |

| C-Mr. Shi | 22 years | Public Servant | 2: Somehow knows it but has never tried before | 5: Definitely yes |

| D-Ms. Wang | 7 years | Researcher | 3: Knows about it and has tried before | 1: Definitely not |

| E-Ms. Wang | 27 years | Manager | 2: Somehow knows about it but has never tried before | 4: Probably yes |

| F-Ms. Xu | 21 years | Student | 4: Knows about it and has tried several times before | 3: Unsure |

| G-Mr. Zhang | 24 years | Teacher | 1: Never heard of it | 4: Probably yes |

| H-Ms. Zhu | 18 years | Lawyer | 3: Knows about it and has tried before | 3: Unsure |

Table A2.

Survey questions and answers.

Table A2.

Survey questions and answers.

| Variable | Proposed Questions | Answers |

|---|---|---|

| Clothing Consumption Behaviour | How many new clothes do you buy on average every month? | A: 5–10 |

| B: 1–2 | ||

| C: Almost none | ||

| D: Around 3 | ||

| E: 10–20 every year | ||

| F: 2–3 | ||

| G: Around 20 every year | ||

| H: 3–4 | ||

| Where do you buy most of the clothes? | A: Online platforms (e.g., Taobao) and malls | |

| B: Online platforms and markets | ||

| C: Malls and brand stores (Uniqlo) | ||

| D: Mainly online platforms | ||

| E: Popular shopping malls (e.g., iapm) | ||

| F: Shopping malls and brand stores (collectpoint) | ||

| G: 70% online and 30% offline | ||

| H: Brand stores (Uniqlo and NiceClaup) | ||

| How long do you usually wear the new clothes you bought? | A: 1–2 years for each piece | |

| B: As long as possible | ||

| C: At least 4–5 years for clothes of good quality and 1–2 years for clothes worn daily | ||

| D: At least 2 years and I will organise my clothes every 2 years | ||

| E: Some stay “forever” and some stay for just a few months | ||

| F: 2–3 years | ||

| G: I don’t really know since I won’t wear some of my clothes, but I also won’t just throw them away | ||

| H: Around half a year to 1 year maybe | ||

| Clothing Recycling Behaviour | How many pieces of clothes will be disposed by you each year on average? | A: Around 4–5 pieces |

| B: 1–2 pieces | ||

| C: Maybe 5–6 | ||

| D: I do not throw my clothes away | ||

| E: 8–10 pieces | ||

| F: Around 5 | ||

| G: None | ||

| H: 10 pieces maybe | ||

| What are the reasons for disposing of these clothes? | A: They are no longer “shiny” enough to me | |

| B: Some clothes do not fit me and some are too old | ||

| C: I don’t like them, or I cannot wear them anymore | ||

| D: | ||

| E: I will throw the clothes once they are damaged | ||

| F: When they no longer match my style and are too old | ||

| G: | ||

| H: A lot, when I don’t like the style, when I cannot fit in them, when the clothes are washed into bad shapes or the colour fades, when they cannot be washed clean | ||

| How do you mostly choose to “dispose” of these used clothes? | A: I just choose the trash can which is closest to me | |

| B: I first choose to see if they can be cut into something that could be directly used for my daily housework (for example, rags or foot mats); I would also like to remake some of them by myself but I don’t have a sewing machine; some of them I also choose to send to family members who may need them; I have also participated in clothing donation organized by our neighbourhood committee | ||

| C: I give them to our community cleaning workers | ||

| D: I try to resell the clothes I really don’t like anymore or have been “hidden back” in my closet, but it has been hard to do this kind of reselling | ||

| E: Of course, I first try to repair some of the damaged clothes, but when they are no longer “repairable” I just leave them in the street trash cans | ||

| F: Our neighbourhood has a good system of sending clothes to each other so we normally just send them to the neighbours | ||

| G: My clothes are always in my closet | ||

| H: I use the community clothing recycling box which has a panda | ||

| After the new waste management rules were implemented, were there any new facilities or publications for clothing recycling in your community? | A: I have never heard of or seen any of them | |

| B: There are some green clothing recycling boxes in my neighbourhood, but they have been there for two years and have nothing to do with the new rules | ||

| C: I know the “panda” boxes, but in my community, they are managed by the community cleaning workers, so I just directly give to them instead | ||

| D: There haven’t been any around my house and to me they are actually not convenient | ||

| E: I will throw the clothes out once they are damaged | ||

| F: I only know “panda” boxes but they are really not used nor close to our community | ||

| G: I have not paid attention to this | ||

| H: There is no publication from the community, and “panda” is still the same there | ||

| Clothing Upcycling Behaviour | Have you encountered “damaged” clothes of yours (e.g., holes, loose threads, broken zipper, etc.)? What do you usually do in this case? | A: Yes, but sometimes I just left them there; this is a kind of interesting status to me |

| B: A lot and I will try to sew them by myself in the first instance | ||

| C: I will go directly to the tailor shop sitting at the roadside in my neighbourhood; the tailor there has perfect skills to make the clothes new again and we like to chat with each other | ||

| D: My mum sometimes helps me with this, and sometimes I go to the tailor shop near me | ||

| E: I really wish I had some sewing skills but I don’t, so I just go to the tailor shops located in the shopping malls with institutional recognition, which usually have better service qualities than the “roadside” tailors | ||

| F: My mom can cover almost all the situations, and when I was in middle school we went to the community tailor but he is no longer working | ||

| G: My grandma often does this for me, and we actually have a community tailor next to my house so sometimes I also go there | ||

| H: I try to fix it by myself first, and if I fail at repairing it I would just throw the clothes out | ||

| Clothing Upcycling Behaviour | Have you ever encountered a situation where the clothes you bought need to be altered again before you can wear them? How often do you encounter this situation? | A: A lot, as I really don’t like some of the original designs but I still like the clothes, so I really want to change the clothes in some way |

| B: Sometimes when the length of the trousers doesn’t fit | ||

| C: I barely have this problem since I will try my best to find the best fit, but sometimes the collar of my shirts needs to be renewed | ||

| D: Sometimes | ||

| E: Quite often for my trousers and suits | ||

| F: Since the store I buy clothes from already provides this kind of service before I get them, I have never been in this situation before | ||

| G: I know my body size so I seldom have this issue | ||

| H: Sometimes, especially in winter if my down jacket get leaks on the feathers | ||

| How often do you usually go to your community tailor shop for these situations? | A: Never, I don’t really know any of them and I cannot speak Shanghai dialect so I think it will be hard to communicate with them | |

| B: Sometimes if I think the work can only be done with sewing machine, otherwise I will still insist to do them myself | ||

| C: Always, they have the best skills to renew my collars | ||

| D: I will immediately use the exchange services instead of finding someone to alter the clothes for me | ||

| E: I will go to community tailor shops if the sewing work is really small and I can be sure the tailor won’t mess it up, but for the majority I still go to the “branded” tailor shop in the shopping mall | ||

| F: Almost never for my personal situation | ||

| G: I will return the clothes if they really don’t fit, and very occasionally I will visit the tailor next to my house to alter the trousers | ||

| H: The community tailor shop is the only place I know for this situation | ||

| Fashion Attitudes and Awareness | What are the factors that influence you the most when you buy clothes? | A: The very unique style of them |

| B: The quality of the clothes and if they are cost-effective for me | ||

| C: The cost-effectiveness, the quality, and the brand | ||

| D: The style, the design, the texture, the materials, the sense of meaning...I really value what the designers want to express in their design, and I think what I buy needs to have meaning in it | ||

| E: The quality, the brand, and the price | ||

| F: The brand, design, quality, and price | ||

| G: The good style and my mood | ||

| H: The popularity of the style, the price, and the quality | ||

| Do you think tailors are needed for your daily life? | A: Not really for now | |

| B: They are not that necessary for me but I’m sure they are for others | ||

| C: Yes, and if they are gone it will be a problem for me | ||

| D: Maybe? | ||

| E: Yes, the good ones are important to me | ||

| F: Maybe sometimes | ||

| G: Not really much but I do like my tailor neighbour | ||

| H: Yes especially when my jackets get holes | ||

| Do you think you need to learn some simple sewing skills? | A: Yes and I’m already learning some because I want to make a pair of gloves for myself | |

| B: I think I already know them well but I may need more tools like a sewing machine | ||

| C: I hope I will never need to learn | ||

| D: I would like to learn, so far I can only sew some badges onto my clothes and I would like to improve | ||

| E: I don’t want to and hope I never need to | ||

| F: I now have basic skills to make some accessories and I think this is already enough for me, going further may take too much time and cost for me | ||

| G: No | ||

| H: I know some basic ones and would like to learn more if they are free for me to learn | ||

| Have you heard about “circular fashion” or “sustainable fashion”? Do these topics influence your consumption choices? | A: Yes, I always keep up with the fashion trends and I think they are the important directions for the future of fashion | |

| B: Never, but if it is related to corporate responsibility then it may influence me | ||

| C: Yes, I have paid attention to these ideas but I’m still looking forward to more substantial progress in these areas instead of just slogans and campaigns | ||

| D: Yes, but they will only influence me if they genuinely show the meaning of it | ||

| E: Yes I have heard of them but I don’t think we are in a good environment for these topics to develop; my personal capability is small and compared to other factors, my quality of life would be the first thing for me to consider | ||

| F: Yes sometimes, since for my dressing culture it is important to make sure the design of the clothes are original and responsible and they will highly influence my buying choice | ||

| G: I only have a very vague idea of them; for me the style is still prior to other factors and sometimes the materials may influence | ||

| H: I have only heard of these topics and I still think my daily needs are of the first priority, but if they become the trend then I may follow |

References

- Rathinamoorthy, R. Circular Fashion. In Circular Economy in Textiles and Apparel; The Textile Institute Book Series; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 13–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake, D.G.K.; Weerasinghe, D. Towards circular economy in fashion: Review of strategies, barriers and enablers. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 2, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, S.; Sandin, G.; Zamani, B.; Peters, G.; Svanström, M. Will Clothing Be Sustainable? Clarifying Sustainable Fashion. In Textiles and Clothing Sustainability: Implications in Textiles and Fashion; Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy/ (accessed on 6 November 2022).

- Euromonitor International Apparel & Footwear 2016 Edition (Volume Sales Trends 2005–2015). Available online: https://www.euromonitor.com/apparel-and-footwear-in-china/report (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Stahel, W.R. The Circular Economy. Nature 2016, 531, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, S.; Peirson-Smith, A. The Sustainability Word Challenge: Exploring Consumer Interpretations of Frequently Used Words to Promote Sustainable Fashion Brand Behaviors and Imagery. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2018, 22, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. Current Situation and Trend of Waste Textile Recycling Industry in China (Part 1). Shanxi Text. Cloth. 2013, 3, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Burman, R.; Zhao, H. Second-Hand Clothing Consumption: A Cross-Cultural Comparison between American and Chinese Young Consumers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, B.V.; Cortimiglia, M.N.; Callegaro-de-Menezes, D.; Ghezzi, A. Innovative and Sustainable Business Models in the Fashion Industry: Entrepreneurial Drivers, Opportunities, and Challenges. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K. Sustainable Production and Consumption by Upcycling: Understanding and Scaling-up Niche Environmentally Significant Behaviour. Doctoral Dissertation, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; Kettley, S. Developing Interventions for Scaling Up UK Upcycling. Energies 2019, 12, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, İ. Design for Sustainability: A Multi-Level Framework from Products to Socio-Technical Systems; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, E. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation; Design Thinking, Design Theory; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meroni, A. Creative Communities: People Inventing Sustainable Ways of Living; POLI Design: Milan, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savage, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A New Sustainability Paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Closing the Loop: New Circular Economy Package|Think Tank|European Parliament. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2016)573899 (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Guldmann, E. Best Practice Examples of Circular Business Models; The Danish Environmental Protection Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.; Jung, H.J.; Lee, Y. Consumers’ Value and Risk Perceptions of Circular Fashion: Comparison between Secondhand, Upcycled, and Recycled Clothing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Sustainable Fashion Supply Chain: Lessons from H&M. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6236–6249. [Google Scholar]

- Jango, K.A.; Wu, J. Collaborative Redesign of Used Clothes as a Sustainable Fashion Solution and Potential Business Opportunity. Fashion. Pract. 2015, 7, 75–97. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, M.A.D.; de Almeida, S.O.; Bollick, L.C.; Bragagnolo, G. Second-Hand Fashion Market: Consumer Role in Circular Economy. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2019, 23, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyer, M.; Dittrich, K. Sustainable Consumer Behavior in Purchasing, Using and Disposing of Clothes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring Attitude–Behavior Gap in Sustainable Consumption: Comparison of Recycled and Upcycled Fashion Products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaky, T. Outsmart Waste: The Modern Idea of Garbage and How to Think Our Way Out of It; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, K. A review on upcycling: Current body of literature, knowledge gaps and a way forward. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Environment, Cultural, Economic and Social Sustainability, Venice, Italy, 13–14 April 2015; pp. 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; Kettley, S. Individual upcycling practice: Exploring the possible determinants of upcycling based on a literature review. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Innovation 2014 Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, 3–4 November 2014; pp. 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, C. Living Simple, Free & Happy: How to Simplify, Declutter Your Home, and Reduce Stress, Debt & Waste; Betterway Home: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Cheng, H.; Liao, Z.; Hu, H. An Account of the Textile Waste Policy in China (1991–2017). J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 1459–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Hong, Y.; Zeng, X.; Dai, X.; Wagner, M. A Systematic Literature Review for the Recycling and Reuse of Wasted Clothing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, L.; Shen, L. Exploring Sustainable Fashion Consumption Behavior in the Post—Pandemic Era: Changes in the Antecedents of Second-Hand Clothing-Sharing in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnane, A. Tailors in 1950s Beijing: Private Enterprise, Career Trajectories, and Historical Turning Points in the Early PRC. Front. Hist. China 2011, 6, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Study on the Hong Bang Tailors; Zhejiang University Press: Zhejiang, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hakken, D.; Mate, P. The culture question in participatory design. In Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference, Windhoek, Namibia, 6–10 October 2014; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J. Early Experiences with Participation in Persuasive Technology Design. In Proceedings of the 12th Participatory Design Conference, Roskilde, Denmark, 12–16 August 2012; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Poderi, G.; Dittrich, Y. Participatory Design and Sustainability—A literature review of PDC Proceedings. In Proceedings of the 15th Participatory Design Conference, Hasselt, Belgium; Genk, Belgium, 20–24 August 2018; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- van Wijk, J.; Zietsma, C.; Dorado, S.; de Bakker, F.G.A.; Martí, I. Social Innovation: Integrating Micro, Meso, and Macro Level Insights from Institutional Theory. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 887–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E. Design Research for Sustainable Social Innovation. In Design Research Now: Essays and Selected Projects; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Types of Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Conditions for Sustainability Innovation: From the Administration of a Technical Challenge to the Management of an Entrepreneurial Opportunity; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gaziulusoy, I.; Veselova, E.; Hodson, E.; Berglund, E.; Öztekin, E.E.; Houtbeckers, E.; Hernberg, H.; Jalas, M.; Fodor, K.; Litowtschenko, M.F. Design for Sustainability Transformations: A Deep Leverage Points Research Agenda for the (Post-)Pandemic Context. Strateg. Des. Res. J. 2021, 14, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E.; Rizzo, F. Small Projects/Large Changes: Participatory Design as an Open Participated Process. CoDesign 2011, 7, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chick, A. Design for Social Innovation: Emerging Principles and Approaches. Iridescent 2012, 2, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y. Fashion Women Have “New Tactics” to Combat Inflation, Dressmakers Start Booming. China Fiber. Insp. 2011, 6, 80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Guan, J.; Yu, X. Shanghai old clothes recycling present study. J. Wool Spinn. Technol. 2019, 47, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hillgren, P.-A.; Seravalli, A.; Emilson, A. Prototyping and Infrastructuring in Design for Social Innovation. CoDesign 2011, 7, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julier, G. Public Sector Innovation. In Economies of Design; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2017; pp. 143–163. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).