Stakeholders’ Perspectives for Taking Action to Prevent Abandoned, Lost, or Otherwise Discarded Fishing Gear in Gillnet Fisheries, Taiwan

Abstract

1. Introduction

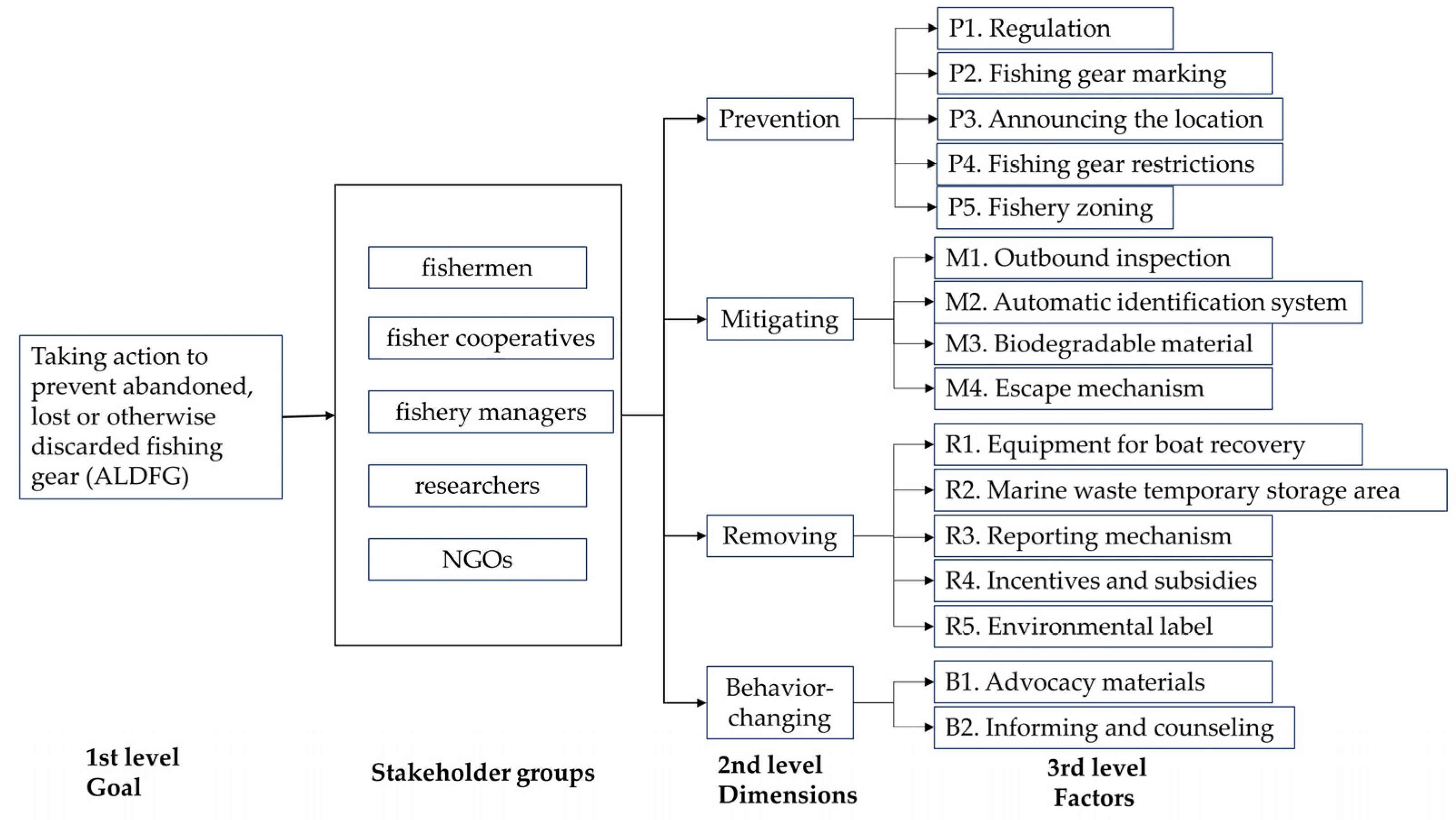

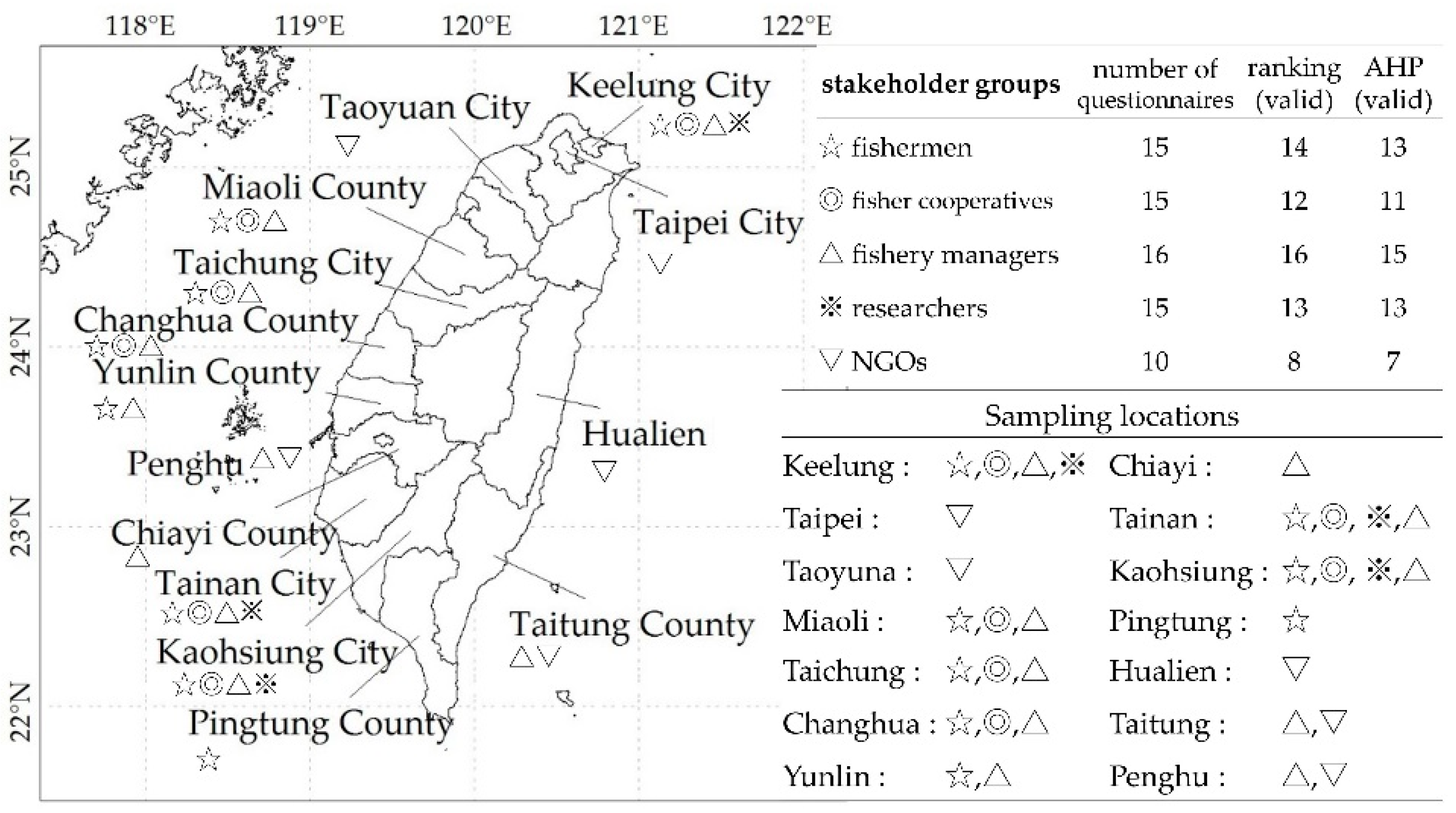

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

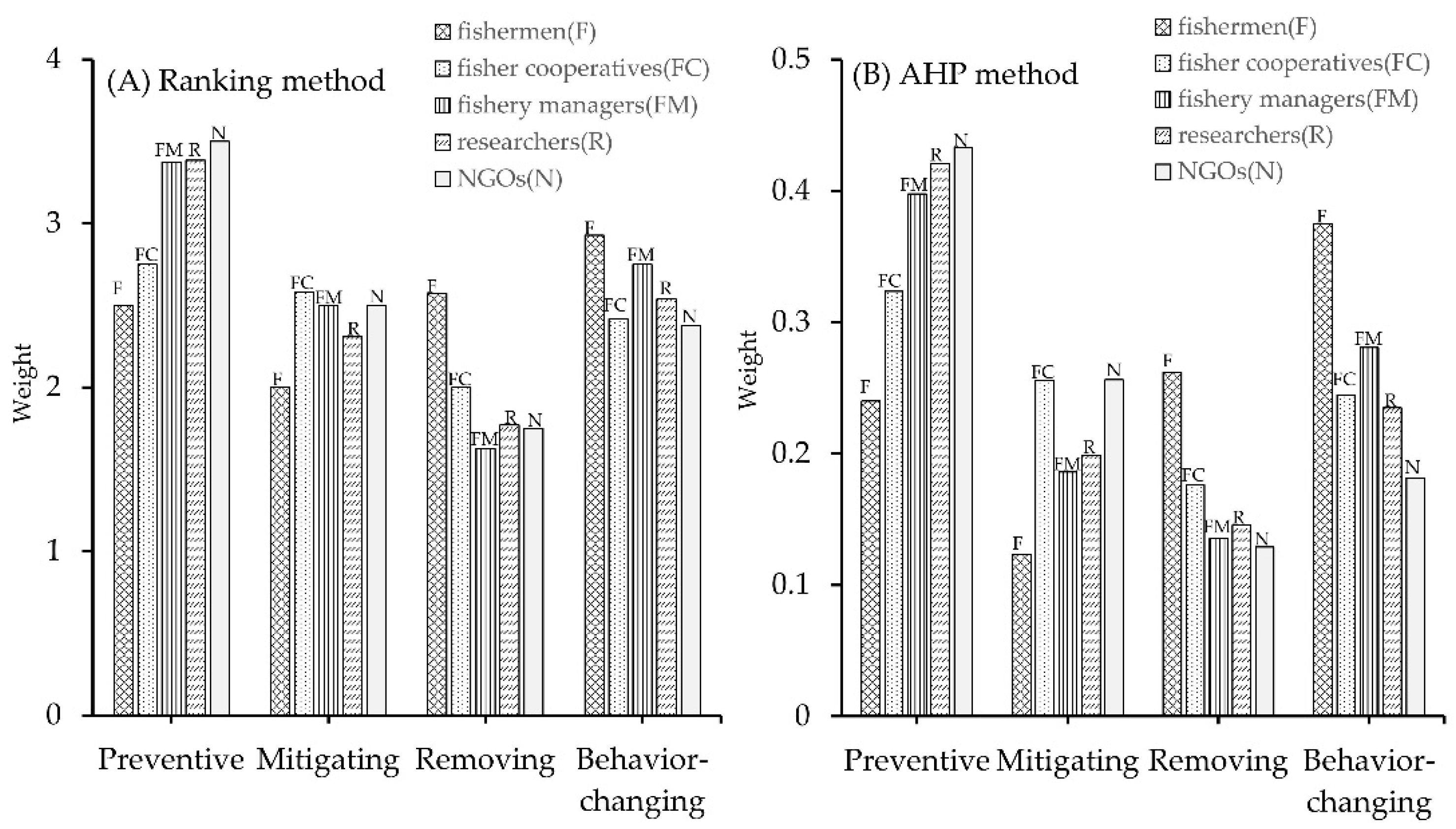

3.1. Stakeholders’ Perspective on the Four Dimensions

3.2. Stakeholders’ Perspective on the Factors

3.2.1. Preventive Dimension

3.2.2. Mitigating Dimension

3.2.3. Removing Dimension

3.2.4. Behavior-Changing Dimension

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Derraik, J.G. The pollution of the marine environment by plastic debris: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2002, 44, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfadyen, G.; Huntington, T.; Cappell, R. Abandoned, Lost or Otherwise Discarded Fishing Gear; Tech Pap No. 523; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; 139p. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, T.R.; Glazer, R.A. Assessing opinions on abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear in the Caribbean. In Proceedings of the Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute, Fort Pierce, FL, USA, 1–5 November 2010; Volume 62, pp. 12–22. Available online: https://nsgl.gso.uri.edu/flsgp/flsgpc09001/data/papers/003.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Gilman, E. Status of international monitoring and management of abandoned, lost and discarded fishing gear and ghost fishing. Mar. Policy 2015, 60, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, P.C.; Haskins, C. Application of Systems Engineering and Sustainable Development Goals towards Sustainable Management of Fishing Gear Resources in Norway. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Wilcox, C.; Vince, J.; Hardesty, B.D. Challenges and misperceptions around global fishing gear loss estimates. Mar. Policy 2021, 129, 104522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolowitz, R.J.; Corps, L.N.; Center, N.F. Lobster, Homarus americanus, trap design and ghost fishing. Mar. Fish. Rev. 1978, 40, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Debris Program (NOAA). Report on Marine Debris Impacts on Coastal and Benthic Habitats. Silver Spring, MD: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Debris Program. 2016. Available online: https://marinedebris.noaa.gov/reports/marine-debris-impacts-coastal-and-benthic-habitats (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Mangi, S.C.; Roberts, C.M. Quantifying the environmental impacts of artisanal fishing gear on Kenya’s coral reef ecosystems. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2006, 52, 1646–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, J.B.; Williamson, D.H.; Russ, G.R.; Willis, B.L. Protected areas mitigate diseases of reef building corals by reducing damage from fishing. Ecology 2015, 96, 2555–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, L.V.; Matthews, J.L.; Hoeksema, B.W. Pollution and coral damage caused by derelict fishing gear on coral reefs around Koh Tao, Gulf of Thailand. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 135, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneli, T.M.; Pereira, P.H.C.; Nunes, J.A.C.C.; Barros, F. Ghost fishing impacts on hydrocorals and associated reef fish assemblages. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 161, 105129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, C.; Heathcote, G.; Goldberg, J.; Gunn, R.; Peel, D.; Hardesty, B.D. Understanding the sources and effects of abandoned, lost, and discarded fishing gear on marine turtles in northern Australia. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, P.; Scotti, G.; Romeo, T.; Fossi, M.C.; Esposito, V.; D’Alessandro, M.; Battaglia, P.; Galgani, F.; Figurella, F.; Pragnell-Raasch, H.; et al. Characterization of seafloor litter on Mediterranean shallow coastal waters: Evidence from Dive Against Debris®, a citizen science monitoring approach. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 150, 110763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consoli, P.; Sinopoli, M.; Deidun, A.; Canese, S.; Berti, C.; Andaloro, F.; Romeo, T. The impact of marine litter from fish aggregation devices on vulnerable marine benthic habitats of the central Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 152, 110928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiappone, M.; White, A.; Swanson, D.W.; Miller, S.L. Occurrence and biological impacts of fishing gear and other marine debris in the Florida Keys. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2002, 44, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asoh, K.; Yoshikawa, T.; Kosaki, R.; Marschall, E. Damage to cauliflower coral by monofilament fishing lines in Hawaii. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 1645–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappone, M.; Dienes, H.; Swanson, D.W.; Miller, S.L. Impacts of lost fishing gear on coral reef sessile invertebrates in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Biol. Conserv. 2005, 121, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dameron, O.J.; Parke, M.; Albins, M.A.; Brainard, R. Marine debris accumulation in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands: An examination of rates and processes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2007, 54, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giskes, I.; Baziuk, J.; Pragnell-Raasch, H.; Perez Roda, A. Report on Good Practices to Prevent and Reduce Marine Plastic Litter from Fishing Activities; FAO: Rome, Italy; IMO: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.A.; Tidd, A. Mapping nearly a century and a half of global marine fishing: 1869–2015. Mar. Policy. 2018, 93, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Valuing Plastic: The Business Case for Measuring, Managing and Disclosing Plastic Use in the Consumer Goods Industry; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2014; Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/9238 (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Scheld, A.M.; Bilkovic, D.M.; Havens, K.J. The dilemma of derelict gear. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Hardesty, B.D.; Wilcox, C. Estimates of fishing gear loss rates at a global scale: A literature review and meta-analysis. Fish Fish. 2019, 20, 1218–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.J.; McIntyre, J.; Smith, A.; Fulton, L.; Walker, T.R.; Brown, C.J. Retrieval of abandoned, lost, and discarded fishing gear in Southwest Nova Scotia, Canada: Preliminary environmental and economic impacts to the commercial lobster industry. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 171, 112766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinkwin, J. Reporting and Retrieval of Lost Fishing Gear: Recommendations for Developing Effective Programmes; FAO: Rome, Italy; IMO: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, E.; Chopin, F.; Suuronen, P.; Kuemlangan, B. Abandoned, Lost and Discarded Gillnets and Trammel Nets: Methods to Estimate Ghost Fishing Mortality, and the Status of Regional Monitoring and Management; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 600; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i5051e/i5051e.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Huntington, T. Development of a Best Practice Framework for the Management of Fishing Gear. Part 1: Overview and Current Status; GGGI: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, E.; Musyl, M.; Suuronen, P.; Chaloupka, M.; Gorgin, S.; Wilson, J.; Kuczenski, B. Highest risk abandoned, lost and discarded fishing gear. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschernij, V.; Larsson, P.O. Ghost fishing by lost cod gill nets in the Baltic Sea. Fish. Res. 2003, 64, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, T.; Nakashima, T.; Nagasawa, N. A review of ghost fishing: Scientific approaches to evaluation and solutions. Fish. Sci. 2005, 71, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Large, P.A.; Graham, N.G.; Hareide, N.R.; Misund, R.; Rihan, D.J.; Mulligan, M.C.; Randall, P.J.; Peach, D.J.; McMullen, P.H.; Harlay, X. Lost and abandoned nets in deep-water gillnet fisheries in the Northeast Atlantic: Retrieval exercises and outcomes. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2009, 66, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardi, K.; Carlson-Bremer, D.; June, J.A.; Antonelis, K.; Broadhurst, G.; Cowan, T. Marine species mortality in derelict fishing nets in Puget Sound, WA and the cost/benefits of derelict net removal. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 60, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, C.; Van Waerebeek, K. Strandings and mortality of cetaceans due to interactions with fishing nets in Ecuador, 2001–2017. In Proceedings of the International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee, Nairobi, Kenya, 10–22 May 2019. Document SC/68A/HIM/17. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Voluntary Guidelines on the Marking of Fishing Gear; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/news/41168 (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- FAO. Report of 2019 FAO Regional Workshops on Best Practices to Prevent and Reduce Abandoned, Lost or Discarded Fishing Gear in Collaboration with the Global Ghost Gear Initiative. Port Vila, Vanuatu, 27–30 May 2019. Bali, Indonesia, 8–11 June 2019. Dakar, Senegal, 14–17 October 2019. Panama City, Panama, 18–23 November 2019; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GGGI. Best Practice Framework for the Management of Fishing Gear; GGGI: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Regulation and management of marine litter. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Bergmann, M., Gutow, L., Klages, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 395–428. [Google Scholar]

- Chumchuen, W.; Krueajun, K. Fishing activities and viewpoints on fishing gear marking of gillnet fishers in small-scale and industrial fishery in the Gulf of Thailand. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 172, 112827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Lin, H.T.; Hu, C.S.; Hsu, C.H.; Yen, N. Volume-based assessment of coastal litter reveals a significant underestimation of marine litter from ocean-based activities in East Asia. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2022, 51, 102214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, N.; Hu, C.S.; Chiu, C.C.; Walther, B.A. Quantity and type of coastal debris pollution in Taiwan: A rapid assessment with trained citizen scientists using a visual estimation method. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, M.P.; Brighouse, G.; Pichon, M. Priorities and strategies for addressing natural and anthropogenic threats to coral reefs in Pacific Island Nations. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2002, 45, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process; McGraw-Hill International: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, P.S.; Muraoka, J.; Nakamoto, S.T.; Pooley, S. Evaluating fisheries management options in Hawaii using analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Fish. Res. 1998, 36, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, K. How to involve stakeholders in fisheries management—A country case study in Trinidad and Tobago. Mar. Policy 2003, 27, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardle, S.; Pascoe, S.; Herrero, I. Management objective importance in fisheries: An evaluation using the analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Environ. Manag. 2004, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, J.R.; Mathiesen, C. Stakeholder preferences for Danish fisheries management of sand eel and Norway pout. Fish. Res. 2006, 77, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himes, A.H. Performance indicator importance in MPA management using a multi-criteria approach. Coast. Manag. 2007, 35, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, S.; Bustarnante, R.; Wilcox, C.; Gibbs, M. Spatial fisheries management: A framework for multi-objective qualitative assessment. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2009, 52, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardle, S.; Pascoe, S. A review of applications of multiple criteria decision making techniques to fisheries. Mar. Resour. Econ. 1999, 14, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattage, P.; Mardle, S. Stakeholder preferences towards conservation versus development for a wetland in Sri Lanka. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 77, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. Game Sense Decision-Making Method: Introduction to AHP, 1st ed.; JUSE Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1986; 218p. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, C.F. Analytic hierarchy process (AHP). In Decision Analysis and Management: A Unison Framework for Total Decision Quality Enhancement, 1st ed.; Chiu, C.W., Ed.; Yeh-Yeh Book Gallery: Taipei, Taiwan, 2005; pp. 223–253. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.; Suuronen, P. Technologies for the marking of fishing gear to identify gear components entangled on marine animals and to reduce abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 129, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C. A Study on Recycling Behavior toward Marine Debris for Fishermen in New Taipei City. Master’s Thesis, National Taipei University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, D.O. The incentive program for fishermen to collect marine debris in Korea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 58, 415–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Liu, T.K. Fill the gap: Developing management strategies to control garbage pollution from fishing vessels. Mar. Policy 2013, 40, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, M.; Mika, K.; Horowitz, C.; Herzog, M.; Leitner, L. Stemming the tide of plastic litter: A global action agenda. Pritzker Environ. Law Policy Briefs 2013, 5, 1–30. Available online: https://escholarship.org/content/qt6j74k1j3/qt6j74k1j3.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Arthur, C.; Sutton-Grier, A.E.; Murphy, P.; Bamford, H. Out of sight but not out of mind: Harmful effects of derelict traps in selected US coastal waters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 86, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good, T.P.; June, J.A.; Etnier, M.A.; Broadhurst, G. Derelict fishing nets in Puget Sound and the Northwest Straits: Patterns and threats to marine fauna. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 60, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhrin, A.V. Tropical cyclones, derelict traps, and the future of the Florida Keys commercial spiny lobster fishery. Mar. Policy 2016, 69, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinkwin, J. Methods to Locate Derelict Fishing Gear in Marine Waters: A Guidance Document; GGGI: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://repository.oceanbestpractices.org/handle/11329/1730 (accessed on 2 November 2022).

| Code | Factors | Description | Suggested Sources * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention | |||

| P1 | Regulation | Development of laws, regulations, and penalties—specify legal provisions and penalties to prevent ALDFG and avoid non-compliance with fishing gear marking regulations. | FC6, FC7 |

| P2 | Fishing gear marking | Fishing gear marking with the owner to ensure traceability—the fishing gear, buoys, and other components must have the owner’s mark or identifier to make the fish traceable. | F8, FO7, FO8, FC1, GD1, F07, GD7, R1 |

| P3 | Announcing the location | Announcement of the location of ALDFG—in conjunction with ALDFG notification, announce the location of the latest ALDFG to prevent gear and net conflicts and navigational risks. | F6, F19, FM11, FM13 |

| P4 | Fishing gear restrictions | Restrictions on fishing gear use—restrict the use of specific fishing gear and limit how and when the gear is used, and conduct gear labeling to reduce conflicts with other fishers or ALDFG. | F1, F3, F4, F5, FM1, FM2, FM9, SF1 |

| P5 | Fishery zoning | Fishery zoning and restricted operations—restrict the use of specific fishing gear in particular areas, carry out the zoning of fishing grounds, and establish no-fishing zones to avoid gear conflicts. | F1, F3, FO3, FM1, FM2, FM9, SF1 |

| Mitigating | |||

| M1 | Outbound inspection | Fishing gear inspection is required when fishing vessels leave port—when fishing vessels operate out of port, check whether the fishing gear conforms to the marking regulations and complies with the requirements concerning preventing ALDFG. | FC2, FC3, FC4, FC5 |

| M2 | Automatic identification system | Instant location reporting for fishing gear in use—the fishing gear can show the position in real-time, visible to fishing vessels and other vessels, or observed on electronic instruments. | F2, F7 |

| M3 | Biodegradable material | Fishing gear made of biodegradable materials—the fishing gear should be made of biodegradable material so that after producing ALDFG, it can decompose in the natural environment. | FM3, GD3, GD6, R2, R3, |

| M4 | Escape mechanism | Adoption of fishing gear with a fish escape mechanism—after ALDFG, the mechanism for fish to escape should still be available on the gear, disabling the gear catch function. | F16, GD2 |

| Removing | |||

| R1 | Equipment for boat recovery | The vessel should have gear retrieval equipment—the vessel should be equipped with gear retrieval equipment for immediate retrieval and removal of gear in the case of an ALDFG. | F17, F18, FM6, FM5, SF2 |

| R2 | Marine waste temporary storage area | Fishing gear retrieval equipment facilities set up on the shore of the fishing port—recycling facilities for discarded fishing gear at fishing port shore facilities, development of fishing waste disposal strategies at the fishing port shore, and provision of places for the fisher to scrap their fishing gear. | F14, F15, P1, P2, P4 |

| R3 | Reporting mechanism | Establishing a mechanism to announce ALDFG—report the date, time, place, reason, identification mark, and other messages of loss and be able to hand it over to the relevant departments for integration. | F12, F20, FO5, FM11, FM12, FM14, P3, R4 |

| R4 | Incentives and subsidies | Set up subsidies or incentives for the removal and recovery of fishing gear—subsidize or reward the removal of lost fishing gear and recovery and reuse of fishing gear. | FO6, P5, SF5, R5, R6, GD5, N3 |

| R5 | Environmental label | Products need to have environmental certification labels—third-party certification with relevant environmental certification labels is required to sell aquatic products. | FO4, F09, SF3, SF4 |

| Behavior changing | |||

| B1 | Advocacy materials | Production of guidebooks and promotional materials for gear marking and ALDFG circulars—produce instruction manuals and related promotional materials on gear marking and ALDFG notification to promote how to prevent ALDFG and what to do in case of ALDFG. | FO1, E1, E2, E3, N1, N2, FM7, FM8 |

| B2 | Informing and counseling | Conducting educational activities such as fisheries counseling and crew training—provide counseling to fishing vessel captains and crew members. Encourage and train them, and conduct educational activities related to ALDFG prevention and gear marking. | FO2, F13, SF1, FM4, FM10 |

| Fishermen (13) | Fisher Cooperatives (11) | Fisheries Managers (15) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | Rank in Dimension | Additive Weight | Rank in Factors | Weight | Rank in Dimension | Additive Weight | Rank in Factors | Weight | Rank in Dimension | Additive Weight | Rank in Factors | |

| Preventive | 0.240 | 0.323 | 0.398 | |||||||||

| P1 | 0.248 | 2 | 0.059 | 5 | 0.279 | 2 | 0.090 | 5 | 0.196 | 3 | 0.078 | 5 |

| P2 | 0.249 | 1 | 0.060 | 4 | 0.291 | 1 | 0.094 | 4 | 0.282 | 1 | 0.112 | 2 |

| P3 | 0.158 | 5 | 0.038 | 11 | 0.139 | 5 | 0.045 | 11 | 0.096 | 5 | 0.038 | 10 |

| P4 | 0.184 | 3 | 0.044 | 8 | 0.146 | 3 | 0.047 | 9 | 0.229 | 2 | 0.091 | 3 |

| P5 | 0.161 | 4 | 0.039 | 10 | 0.145 | 4 | 0.047 | 10 | 0.196 | 4 | 0.078 | 6 |

| Mitigating | 0.123 | 0.256 | 0.186 | |||||||||

| M1 | 0.340 | 1 | 0.042 | 9 | 0.436 | 1 | 0.112 | 3 | 0.233 | 3 | 0.043 | 9 |

| M2 | 0.289 | 2 | 0.036 | 12 | 0.186 | 3 | 0.048 | 8 | 0.113 | 4 | 0.021 | 15 |

| M3 | 0.185 | 3 | 0.023 | 14 | 0.222 | 2 | 0.057 | 6 | 0.394 | 1 | 0.073 | 7 |

| M4 | 0.185 | 4 | 0.023 | 15 | 0.156 | 4 | 0.040 | 13 | 0.260 | 2 | 0.048 | 8 |

| Removing | 0.262 | 0.176 | 0.135 | |||||||||

| R1 | 0.093 | 4 | 0.024 | 13 | 0.208 | 3 | 0.037 | 14 | 0.253 | 1 | 0.034 | 11 |

| R2 | 0.173 | 3 | 0.045 | 7 | 0.293 | 1 | 0.051 | 7 | 0.160 | 4 | 0.022 | 14 |

| R3 | 0.188 | 2 | 0.049 | 6 | 0.200 | 4 | 0.035 | 15 | 0.211 | 3 | 0.029 | 13 |

| R4 | 0.470 | 1 | 0.123 | 3 | 0.230 | 2 | 0.041 | 12 | 0.241 | 2 | 0.033 | 12 |

| R5 | 0.076 | 5 | 0.020 | 16 | 0.069 | 5 | 0.012 | 16 | 0.134 | 5 | 0.018 | 16 |

| Behavior | 0.375 | 0.245 | 0.281 | |||||||||

| B1 | 0.42 | 2 | 0.157 | 2 | 0.486 | 2 | 0.119 | 2 | 0.288 | 2 | 0.081 | 4 |

| B2 | 0.58 | 1 | 0.218 | 1 | 0.514 | 1 | 0.126 | 1 | 0.712 | 1 | 0.200 | 1 |

| Researchers (13) | NGOs (7) | |||||||||||

| Weight | Rank in dimension | Additive weight | Rank in factors | Weight | Rank in dimension | Additive weight | Rank in factors | |||||

| Preventive | 0.421 | 0.433 | ||||||||||

| P1 | 0.375 | 1 | 0.158 | 2 | 0.372 | 1 | 0.161 | 1 | ||||

| P2 | 0.261 | 2 | 0.110 | 3 | 0.276 | 2 | 0.120 | 3 | ||||

| P3 | 0.078 | 5 | 0.033 | 12 | 0.069 | 5 | 0.030 | 13 | ||||

| P4 | 0.151 | 3 | 0.064 | 5 | 0.151 | 3 | 0.065 | 5 | ||||

| P5 | 0.136 | 4 | 0.057 | 7 | 0.131 | 4 | 0.057 | 7 | ||||

| Mitigating | 0.199 | 0.256 | ||||||||||

| M1 | 0.405 | 1 | 0.081 | 4 | 0.414 | 1 | 0.106 | 4 | ||||

| M2 | 0.176 | 3 | 0.035 | 11 | 0.178 | 3 | 0.046 | 8 | ||||

| M3 | 0.262 | 2 | 0.052 | 8 | 0.237 | 2 | 0.061 | 6 | ||||

| M4 | 0.157 | 4 | 0.031 | 13 | 0.171 | 4 | 0.044 | 9 | ||||

| Removing | 0.145 | 0.129 | ||||||||||

| R1 | 0.177 | 3 | 0.026 | 14 | 0.174 | 4 | 0.022 | 15 | ||||

| R2 | 0.147 | 4 | 0.021 | 15 | 0.261 | 2 | 0.034 | 11 | ||||

| R3 | 0.253 | 2 | 0.037 | 10 | 0.196 | 3 | 0.025 | 14 | ||||

| R4 | 0.311 | 1 | 0.045 | 9 | 0.309 | 1 | 0.040 | 10 | ||||

| R5 | 0.112 | 5 | 0.016 | 16 | 0.060 | 5 | 0.008 | 16 | ||||

| Behavior | 0.235 | 0.181 | ||||||||||

| B1 | 0.246 | 2 | 0.058 | 6 | 0.182 | 2 | 0.033 | 12 | ||||

| B2 | 0.754 | 1 | 0.177 | 1 | 0.818 | 1 | 0.148 | 2 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, C.-M. Stakeholders’ Perspectives for Taking Action to Prevent Abandoned, Lost, or Otherwise Discarded Fishing Gear in Gillnet Fisheries, Taiwan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010318

Yang C-M. Stakeholders’ Perspectives for Taking Action to Prevent Abandoned, Lost, or Otherwise Discarded Fishing Gear in Gillnet Fisheries, Taiwan. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010318

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Ching-Min. 2023. "Stakeholders’ Perspectives for Taking Action to Prevent Abandoned, Lost, or Otherwise Discarded Fishing Gear in Gillnet Fisheries, Taiwan" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010318

APA StyleYang, C.-M. (2023). Stakeholders’ Perspectives for Taking Action to Prevent Abandoned, Lost, or Otherwise Discarded Fishing Gear in Gillnet Fisheries, Taiwan. Sustainability, 15(1), 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010318