Green Lifestyle: A Tie between Green Human Resource Management Practices and Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Underpinning Theory

2.2. Literature Review

2.2.1. Green Human Resource Management GHRM

2.2.2. Green Recruitment

2.2.3. Green Learning and Development

2.2.4. Green Compensation

2.2.5. Green Empowerment

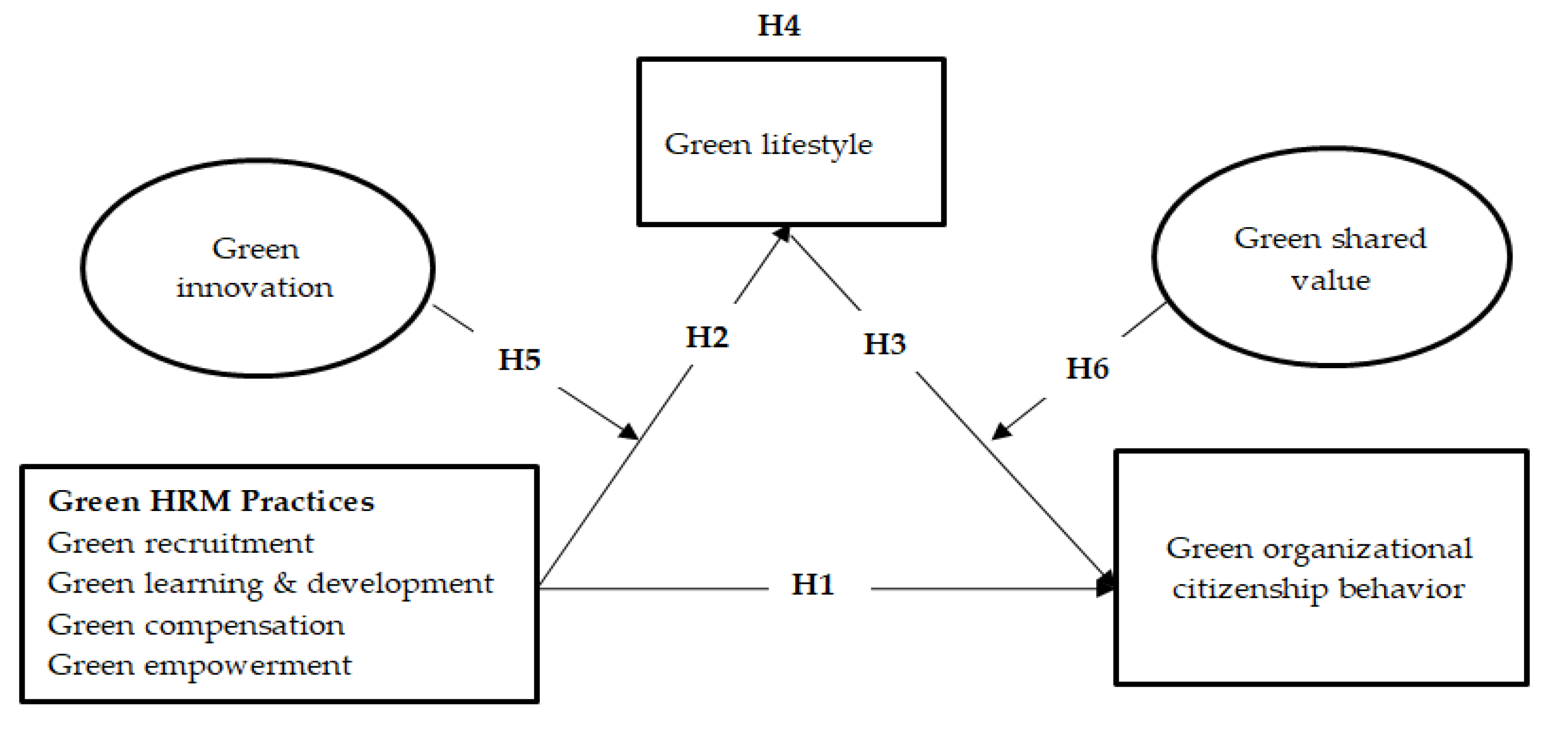

2.3. Hypotheses Development

2.3.1. Green HRM Practices and Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior

2.3.2. Green HRM Practices and Green Lifestyle

2.3.3. Green Lifestyle and Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior

2.3.4. Green HRM Practices and Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior with the Mediating Effect of a Green Lifestyle

2.3.5. Green HRM Practices and Green Lifestyle with the Moderating Effect of Green Innovation

2.3.6. Green Lifestyle and Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior by Moderating Effect of Green Shared Value

2.4. Conceptual Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Context and Data Collection

3.2. Demographics

3.3. Measures

3.4. Common Method Biased

4. Results

4.1. Data Analysis Techniques

4.2. Measurement Model

Discriminant Validity

4.3. Structural Model

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Implications, Limitations and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McMichael, A.J.; Powles, J.W.; Butler, C.D.; Uauy, R. Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet 2007, 370, 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmagrhi, M.H.; Ntim, C.G.; Elamer, A.A.; Zhang, Q. A study of environmental policies and regulations, governance structures, and environmental performance: The role of female directors. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktadir, M.A.; Ali, S.M.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Shaikh, M.A.A. Assessing challenges for implementing Industry 4.0: Implications for process safety and environmental protection. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 117, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Jantan, A.H.; Yusoff, Y.M.; Chong, C.W.; Hossain, M.S. Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) Practices and Millennial Employees’ Turnover Intentions in Tourism Industry in Malaysia: Moderating Role of Work Environment. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 0972150920907000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawashdeh, A.M. The impact of green human resource management on organizational environmental performance in Jordanian health service organizations. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, Y.M.; Nejati, M.; Kee, D.M.H.; Amran, A. Linking Green Human Resource Management Practices to Environmental Performance in Hotel Industry. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; E Jackson, S. Green human resource management research in emergence: A review and future directions. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 769–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Tučková, Z.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J. Greening the hospitality industry: How do green human resource management practices influence organizational citizenship behavior in hotels? A mixed-methods study. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaei, A.; Nejati, M.; Mohd Yusoff, Y. Green human resource management: A two-study investigation of antecedents and outcomes. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 1041–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooi, L.W.; Liu, M.S.; Lin, J.J.J. Green human resource management and green organizational citizenship behavior: Do green culture and green values matter? Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 43, 763–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, M.F.; Omar, M.K.; Wei, F.; Rasheed, M.I.; Hameed, Z. Green HRM and psychological safety: How transformational leadership drives follower’s job satisfaction. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2269–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, S.K.; Othman, M. The impact of green human resource management practices on sustainable performance in healthcare organisations: A conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, L.; Gan, X.; Xu, T.; Long, R.; Qiao, L.; Zhu, H. A new perspective to promote organizational citizenship behaviour for the environment: The role of transformational leadership. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 118002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genoveva, G.; Syahrivar, J. Green Lifestyle among Indonesian Millennials: A Comparative Study between Asia and Europe. J. Environ. Account. Manag. 2020, 8, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, S.-C.; Mohd, I.H.; Kamaruddin; Binti, J.N.; Noh, M.N. Impact of Green Human Resource Management Practices Towards Green Lifestyle and Job Performance. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Afsar, B.; Maqsoom, A.; Shahjehan, A.; Afridi, S.A.; Nawaz, A.; Fazliani, H. Responsible leadership and employee’s proenvironmental behavior: The role of organizational commitment, green shared vision, and internal environmental locus of control. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktadir, M.A.; Dwivedi, A.; Ali, S.M.; Paul, S.K.; Kabir, G.; Madaan, J. Antecedents for greening the workforce: Implications for green human resource management. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 1135–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombiak, E. Green human resource management- the latest trend or strategic necessity? Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 6, 1647–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lai, S.B.; Wen, C.T. The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, T.Y.; Chuang, C.M. Creating Shared Value Through Implementing Green Practices for Star Hotels. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 21, 678–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikar, T.; Hussain, S.; Malik, M.I.; Hyder, S.; Kaleem, M.; Saqib, A. Green human resource management and pro-environmental behaviour nexus with the lens of AMO theory. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2124603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, A.; Khan, N.A.; Bharadwaj, S.; Parvin, F. Green human resource management: A transformational vision towards environmental sustainability. Int. J. Bus. Environ. 2021, 12, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saeed, B.B.; Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting employee’s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Chavez, R.; Feng, M.; Wong, C.Y.; Fynes, B. Green human resource management and environmental cooperation: An ability-motivation-opportunity and contingency perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 219, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Rasheed, F.; Waseem, M.; Tabash, M.I. Green human resource management and environmental performance: The role of green supply chain management practices. Benchmarking Int. J. 2021, 29, 2881–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Pathak, S.; Werner, S. When do international human capital enhancing practices benefit the bottom line? An ability, motivation, and opportunity perspective. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 784–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, Y.S.; Garg, R. The simultaneous effect of green ability-motivation-opportunity and transformational leadership in environment management: The mediating role of green culture. Benchmarking 2021, 28, 830–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, A.; Boxall, P. Lean production, employee learning and workplace outcomes: A case analysis through the ability-motivation-opportunity framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2013, 23, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Altinay, L. Green HRM, environmental awareness and green behaviors: The moderating role of servant leadership. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Ramayah, T.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Sehnem, S.; Mani, V. Pathways towards sustainability in manufacturing organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Z.; Khan, I.U.; Islam, T.; Sheikh, Z.; Naeem, R.M. Do green HRM practices influence employees’ environmental performance? Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 1061–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulet, R.; Holland, P.; Morgan, D. A meta-review of 10 years of green human resource management: Is Green HRM headed towards a roadblock or a revitalisation? Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2021, 59, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, A.O.; Esen, E. Green human resource management and environmental sustainability. Int. J. Acad. Multidiscip. Res. 2019, 9, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Longoni, A.; Luzzini, D. Translating stakeholder pressures into environmental performance—The mediating role of green HRM practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 262–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, A.O.; Tan, C.N.L.; Alias, M. Linking green HRM practices to environmental performance through pro-environment behaviour in the information technology sector. Soc. Responsib. J. 2022, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Green indoor and outdoor environment as nature-based solution and its role in increasing customer/employee mental health, well-being, and loyalty. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzone, M.; Guerci, M.; Lettieri, E.; Huisingh, D. Effects of ‘green’ training on pro-environmental behaviors and job satisfaction: Evidence from the Italian healthcare sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Ashraful, A.; Niu, X.; Rounok, N. Effect of green human resource management (GHRM) overall on organization’s environmental performance. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. (2147–4478) 2021, 10, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Chen, Y. Linking environmental management practices and organizational citizenship behaviour for the environment: A social exchange perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 3552–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M. How Are Green Human Resource Management Practices Promoting Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviour in the Workplace Within the New Zealand Wine Industry? Doctoral dissertation, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, S.; Khan, K.U.; Atlas, F.; Irfan, M. Stimulating student’s pro-environmental behavior in higher education institutions: An ability–motivation–opportunity perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 24, 4128–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Karatepe, O.M. Green human resource management, perceived green organizational support and their effects on hotel employees’ behavioral outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3199–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J. How green human resource management can promote green employee behavior in China: A technology acceptance model perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amrutha, V.N.; Geetha, S.N. A systematic review on green human resource management: Implications for social sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzone, M.; Guerci, M.; Lettieri, E.; Redman, T. Progressing in the change journey towards sustainability in healthcare: The role of “Green” HRM. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 122, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F.G.; Ashraf, Z.; Gilal, N.G.; Gilal, R.G.; Channa, N.A. Promoting environmental performance through green human resource management practices in higher education institutions: A moderated mediation model. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1579–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Integrating green strategy and green human resource practices to trigger individual and organizational green performance: The role of environmentally-specific servant leadership. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1193–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emilisa, N.; Michelle; Lunarindiah, G. Concequences of Green Human Resource Management: Perspective of Professional Event Organizer Employees in Jakarta. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2020, 9, 361–372. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.E.; Renwick, D.W.S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Muller-Camen, M. State-of-the-art and future directions for green human resource management. Ger. J. Res. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 25, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Disentangling green service innovative behavior among hospitality employees: The role of customer green involvement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, F.; Du, J.; Khan, I.; Shahbaz, M.; Murad, M. Untangling the influence of organizational compatibility on green supply chain management efforts to boost organizational performance through information technology capabilities. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 122029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Green human resource practices and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The roles of collective green crafting and environmentally specific servant leadership. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1167–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.Y.; Mughal, Y.H.; Azam, T.; Cao, Y.; Wan, Z.; Zhu, H.; Thurasamy, R. Corporate Social Responsibility, Green Human Resources Management, and Sustainable Performance: Is Organizational Citizenship Behavior towards Environment the Missing Link? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mei, S.; Guo, Y. Green human resource management, green organization identity and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The moderating effect of environmental values. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2021, 15, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, P.; Aqueveque, C.; Duran, I.J. Do employees value strategic CSR? A tale of affective organizational commitment and its underlying mechanisms. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2019, 28, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q. Exploring the Impact of Responsible Leadership on Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: A Leadership Identity Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Florenthal, B.; Arling, P. Do Green Lifestyle Consumers Appreciate Low Involvement Green Products? Mark. Manag. J. 2011, 21, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, N.; Nik Mahmood, N.H.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Ramayah, T.; Noor Faezah, J.; Khalid, W. Green Human Resource Management for organisational citizenship behaviour towards the environment and environmental performance on a university campus. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Aina, R.; Atan, T. The impact of implementing talent management practices on sustainable organizational performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, Y.H. The determinants of green radical and incremental innovation performance: Green shared vision, green absorptive capacity, and green organizational ambidexterity. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7787–7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2014, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Fassott, G. Testing Moderating Effects in PLS Path Models: An Illustration of Available Procedures. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 713–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions—Google Books; Aiken, L.S., West, S.G., Reno, R.R., Eds.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinn, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modelling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.W. Corporate sustainable development strategy: Effect of green shared vision on organization members’ behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators | Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Human Resource Management Practices | 0.958 | 0.963 | 0.667 | ||

| GHRMP1 | 0.855 | 4.001 | |||

| GHRMP2 | 0.821 | 3.507 | |||

| GHRMP3 | 0.798 | 2.899 | |||

| GHRMP4 | 0.769 | 3.058 | |||

| GHRMP5 | 0.833 | 3.557 | |||

| GHRMP6 | 0.827 | 3.719 | |||

| GHRMP7 | 0.840 | 3.343 | |||

| GHRMP8 | 0.823 | 3.301 | |||

| GHRMP9 | 0.847 | 3.407 | |||

| GHRMP10 | 0.755 | 3.216 | |||

| GHRMP11 | 0.825 | 3.359 | |||

| GHRMP12 | 0.801 | 3.190 | |||

| GHRMP13 | 0.795 | 3.106 | |||

| Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior | 0.948 | 0.957 | 0.733 | ||

| GRENB1 | 0.833 | 2.597 | |||

| GRENB2 | 0.854 | 3.009 | |||

| GRENB3 | 0.854 | 3.217 | |||

| GRENB4 | 0.842 | 2.975 | |||

| GRENB5 | 0.859 | 3.139 | |||

| GRENB6 | 0.853 | 2.898 | |||

| GRENB7 | 0.872 | 3.144 | |||

| GRENB8 | 0.883 | 3.758 | |||

| Green Innovation | 0.907 | 0.935 | 0.782 | ||

| GRENI1 | 0.873 | 2.742 | |||

| GRENI2 | 0.923 | 3.795 | |||

| GRENI3 | 0.907 | 3.420 | |||

| GRENI4 | 0.833 | 2.302 | |||

| Green Lifestyle | 0.773 | 0.869 | 0.690 | ||

| GRENL1 | 0.887 | 2.238 | |||

| GRENL2 | 0.840 | 2.105 | |||

| GRENL3 | 0.759 | 1.297 | |||

| Green Shared Value | 0.906 | 0.934 | 0.780 | ||

| GRENV1 | 0.910 | 3.531 | |||

| GRENV2 | 0.879 | 2.752 | |||

| GRENV3 | 0.892 | 2.614 | |||

| GRENV4 | 0.851 | 2.252 |

| Indicators | GHRMP | GRENB | GRENI | GRENL | GRENV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHRMP1 | 0.855 | 0.236 | 0.284 | 0.230 | 0.091 |

| GHRMP10 | 0.775 | 0.262 | 0.248 | 0.236 | 0.171 |

| GHRMP11 | 0.825 | 0.242 | 0.356 | 0.278 | 0.176 |

| GHRMP12 | 0.801 | 0.218 | 0.320 | 0.222 | 0.138 |

| GHRMP13 | 0.795 | 0.137 | 0.258 | 0.222 | 0.133 |

| GHRMP2 | 0.821 | 0.204 | 0.268 | 0.198 | 0.143 |

| GHRMP3 | 0.798 | 0.292 | 0.335 | 0.220 | 0.140 |

| GHRMP4 | 0.769 | 0.180 | 0.271 | 0.164 | 0.090 |

| GHRMP5 | 0.833 | 0.208 | 0.314 | 0.197 | 0.125 |

| GHRMP6 | 0.827 | 0.232 | 0.332 | 0.225 | 0.110 |

| GHRMP7 | 0.840 | 0.215 | 0.331 | 0.243 | 0.130 |

| GHRMP8 | 0.823 | 0.226 | 0.296 | 0.185 | 0.182 |

| GHRMP9 | 0.847 | 0.249 | 0.303 | 0.245 | 0.125 |

| GRENB1 | 0.253 | 0.833 | 0.228 | 0.239 | 0.225 |

| GRENB2 | 0.266 | 0.854 | 0.309 | 0.269 | 0.214 |

| GRENB3 | 0.212 | 0.854 | 0.313 | 0.222 | 0.191 |

| GRENB4 | 0.228 | 0.842 | 0.355 | 0.224 | 0.231 |

| GRENB5 | 0.220 | 0.859 | 0.288 | 0.184 | 0.200 |

| GRENB6 | 0.199 | 0.853 | 0.275 | 0.214 | 0.231 |

| GRENB7 | 0.286 | 0.872 | 0.284 | 0.212 | 0.271 |

| GRENB8 | 0.220 | 0.883 | 0.352 | 0.228 | 0.171 |

| GRENI1 | 0.315 | 0.269 | 0.873 | 0.274 | 0.101 |

| GRENI2 | 0.325 | 0.337 | 0.923 | 0.280 | 0.061 |

| GRENI3 | 0.358 | 0.334 | 0.907 | 0.249 | 0.137 |

| GRENI4 | 0.317 | 0.300 | 0.833 | 0.242 | 0.064 |

| GRENL1 | 0.250 | 0.242 | 0.262 | 0.887 | 0.041 |

| GRENL2 | 0.163 | 0.205 | 0.230 | 0.840 | 0.139 |

| GRENL3 | 0.257 | 0.204 | 0.242 | 0.759 | 0.065 |

| GRENV1 | 0.170 | 0.198 | 0.106 | 0.067 | 0.910 |

| GRENV2 | 0.116 | 0.211 | 0.116 | 0.106 | 0.879 |

| GRENV3 | 0.158 | 0.265 | 0.056 | 0.080 | 0.892 |

| GRENV4 | 0.143 | 0.217 | 0.093 | 0.079 | 0.851 |

| Indicators | GHRMP | GRENB | GRENI | GRENL | GRENV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHRMP | 0.817 | ||||

| GRENB | 0.278 | 0.856 | |||

| GRENI | 0.371 | 0.350 | 0.885 | ||

| GRENL | 0.273 | 0.263 | 0.296 | 0.831 | |

| GRENV | 0.167 | 0.256 | 0.102 | 0.094 | 0.883 |

| Indicators | GHRMP | GRENB | GRENI | GRENL | GRENV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHRMP | |||||

| GRENB | 0.284 | ||||

| GRENI | 0.397 | 0.379 | |||

| GRENL | 0.309 | 0.304 | 0.351 | ||

| GRENV | 0.177 | 0.270 | 0.116 | 0.118 |

| Hypothesis | Relationships | β | T | p | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | |||||

| H1 | GHRMP -> GRENB | 0.192 | 3.078 | 0.002 | Accepted |

| H2 | GHRMP -> GRENL | 0.159 | 3.011 | 0.003 | Accepted |

| H3 | GRENL -> GRENB | 0.193 | 3.293 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| Indirect Effect | |||||

| H4 | GHRMP -> GRENL -> GRENB | 0.031 | 2.184 | 0.029 | Accepted |

| Moderating Effects | |||||

| H5 | GRENI × GHRMP -> GRENL | −0.084 | 1.540 | 0.124 | Rejected |

| H6 | GRENV × GRENL -> GRENB | 0.101 | 2.262 | 0.024 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meng, J.; Murad, M.; Li, C.; Bakhtawar, A.; Ashraf, S.F. Green Lifestyle: A Tie between Green Human Resource Management Practices and Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010044

Meng J, Murad M, Li C, Bakhtawar A, Ashraf SF. Green Lifestyle: A Tie between Green Human Resource Management Practices and Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Jianfeng, Majid Murad, Cai Li, Ayesha Bakhtawar, and Sheikh Farhan Ashraf. 2023. "Green Lifestyle: A Tie between Green Human Resource Management Practices and Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010044

APA StyleMeng, J., Murad, M., Li, C., Bakhtawar, A., & Ashraf, S. F. (2023). Green Lifestyle: A Tie between Green Human Resource Management Practices and Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability, 15(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010044