Abstract

Evidence from well-established theories of various disciplines manifests that, in the current technology-led world, continued professional development (CPD) of information professionals plays a paramount role in the uplift of institutions. CPD of university library professionals via e-learning programs leads to the implementation of user-centric-services through the initiation of emerging technological tools and the latest methods of service-delivery. The focus of this study is to shed light on the factors influencing e-learning for CPD of working librarians, challenges being encountered for e-learning adoption, and to propose the best practices for designing an efficient e-learning portfolio. For meeting the focused study-objectives, the authors applied PRISMA guidelines and procedures. An extensive search was conducted utilizing the world’s 16 leading e-databases and digital tools containing the most relevant core studies. Consequently, 30 impact factor research papers published in renowned databases were included through the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion process. Findings revealed that different factors—including organizational survival, continuous changes, adoption of emerging technologies, and professional growth—encouraged e-learning for CPD of information professionals. The study results showed that four main challenges—technical difficulties, lack of funds, reliance upon conventional models, and overwhelming work-load—were encountered for e-learning adoption. The authors proposed a framework for the development of an effective and efficient e-learning portfolio for building professional expertise among university librarians to support the organizational vision and mission statement. The recommended framework is based upon emergent categories and sub-categories extracted via thematic analysis of the existing empirical studies. This study has theoretical insights for the researchers through valuable addition in the body of literature and practical considerations for policy implementers to construct sustainable policies for devising e-learning programs to develop professional expertise in the university library workforce for attainment of value-added outcomes.

1. Introduction

The term ‘e-learning’ is used in several ways. It includes such terms as networked collaborative learning, computer-based collaborative learning, online learning, web-supported learning, and computer-assisted learning [1,2]. The rise of various technological innovations has led to the spread of e-learning [3,4,5,6]. Slebodnik [7] (pp. 33–34) mentioned that e-learning helps information professionals in different ways:

“Particularly in libraries where in-person instruction is not always feasible, online tutorials can reach more people than a typical instruction team. Tutorials can provide 24/7 access to library information as well as instruction in information literacy skills and electronic library orientation”.

E-learning for continuing professional development (CPD) is a vital factor to implement emerging technologies according to the changing job requirements for organizational survival [8]. There is a strong positive connection between CPD and enhanced work performance of librarians [9]. Ample availability of e-learning courses provides free continuing professional development opportunities to the library professionals with Internet connectivity to improve professional skills [10].

Professional development activities provided in an online environment enable librarians to grow and flourish professionally [11]. E-learning programs, including webinars and online workshops, are a cost effective means to engage early-career library professionals in continuing professional development [12,13]. Institutional changes in higher education due to rapid technological advancements stimulate information professionals towards professional development [14] for enhancing learning and skills to provide smart library services [15,16,17,18].

Different technical difficulties—including Adobe connect software, bandwidth issues, and uploading files to adobe connect cause unnecessary delays for e-learners [11], lack of finance for CPD, lack of funding to attend professional conferences and workshops, interruptible internet, and lack of leadership—are certain barriers being encountered in the adoption of e-learning [19].

Financial support is necessary to attend continued professional development programs [20]. Collaborative environments and blended learning are helpful in the workplace to enhance professional growth of librarians [21,22,23].

After an e-learning course has concluded, a satisfaction survey should be distributed among attendees for receiving their valuable feedback to refine online courses going forward [11,12]. Social media tools are very productive in the context of professional development to polish the technical expertise of librarians [24]. Professional development courses should be developed by keeping in view the organizational strategic planning to create technological skills among academic librarians [25,26].

Library administrators should help librarians to attend e-learning programs for professional development through adequate funding and a flexible organizational environment [27,28,29]. Supportive leaders, personal interest, congenial organizational atmosphere, rewards, and availability of funds to attend CPD activities also enable library professionals to develop sustainable professional competence in the field [30,31].

1.1. Statement of Problem and Rationale

In the current age, e-learning has opened innovative paths to professional development for the provision of value-added services to the target users’ community in both an effective and efficient manner. E-learning provides in-service training to library professionals to carry out user-centered services. Continued professional development via e-learning programs helps library workers keep up to date on the trends and tools necessary to grow professionally.

Although sufficient literature is available on various dimensions related to e-learning and professional development, those empirical studies have specific geographical domains. Existing literature revealed that no comprehensive systematic literature review had been conducted on e-learning for CPD of academic library professionals. This study seeks to address the changing landscape of the librarianship by manifesting factors influencing e-learning, challenges being encountered for e-learning adoption, and the best practices to develop an efficient e-portfolio.

The current study is of paramount importance for information professionals, government representatives, higher education bodies, decision-makers, and other stakeholders to construct efficient methods to implement e-learning strategies for the career development of librarians. Practical solutions revealed through this study to design an e-learning portfolio will prove fruitful and dynamic in encouraging innovative learning based on artificial intelligence (AI)-powered applications. Findings related to challenges being faced to implement e-learning for CPD will assist future researchers to further explore and expand this area. This study will add an important addition to the body of extant literature and offer a benchmark to decision-makers for developing tools and techniques to expand professional competencies among library professionals.

This study is, indeed, useful for library leadership to apply the emerging technologies to benefit from e-learning for career development to deliver value-added services to the end users of university libraries. The study has theoretical insights for the researchers and practical implications for policy-makers to promote e-learning for professional development of librarians. The proposed framework based on empirical evidence is valuable in developing documented policies related to e-learning for continued professional development of library professionals carrying out services in the university libraries.

1.2. Research Questions

The following research questions were established:

- RQ1.

- What are the factors influencing e-learning for continued professional development (CPD) of working librarians?

- RQ2.

- Which challenges are encountered in e-learning adoption?

- RQ3.

- What are the best practices to design an efficient e-learning portfolio?

2. Materials and Methods

The research team applied the “Preferred Reporting Items for the Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis” (PRISMA) procedures [32]. “PRISMA is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic review and meta-analysis. PRISMA is used for reporting of review, evaluating randomized trials, but it can also be used as a basis for reporting systematic review” [33]. Liberati et al. [34] (p. 1) mentioned:

“provided key characteristics of a systematic review are: (a) a clearly stated set of objectives with an explicit, reproducible methodology; (b) a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies that would meet the eligibility criteria; (c) an assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies, for example through the assessment of the risk of bias; and (d) systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies”.

PRISMA is based upon four major stages with various related steps. The first stage is planning, which is based upon focused research questions and the search strategy. The second stage is selection, wherein the accessed data are sorted and extrapolated. The third stage is extraction—the searched literature is evaluated the through rigorous criteria. The fourth and final stage is data synthesis, which is applied to analyze the data. These four stages have been applied in the current study. These are detailed as follows:

2.1. Stage One: Planning

- (1).

- Focused research questions

Research questions of the study covering specific scope are: factors influencing e-learning for CPD of information professionals, challenges being encountered for e-learning adoption, and the best practices to design an efficient e-learning portfolio.

- (2).

- Search strategy

Following search strategies were applied related to search terms, sources of literature, and the process of retrieving the literature.

2.1.1. Search Terms

Through pre-determined criteria, search-terms were formulated. The following search-strings were developed:

- Formulation of keywords/constructs/variables from title of the article as main thought.

- Development of a general study objective and choose some words from that showing clear direction of the instant research.

- Usage of keywords used by other researchers in their published studies.

- Relevant terms.

- Employment of Boolean operators “AND” to retrieve combined records of both terms, “OR” to include substitute terms and “NOT” to exclude keywords in search terms for finding the most relevant documents.

All relevant documents were accessed by using different searching methods and techniques. Search terms used in 16 databases are manifested as below:

- (“E-learning” OR “Factors influencings e-learning” OR “Benefits of online learning” OR “Challenges being encountered for e-learning adoption”)

- AND

- (“Online learning AND continued professional development” OR “Role of different factors in the spread e-learning for CPD” OR “Impact of e-learning” OR “Causes to attend professional development programs” OR “e-learning portfolio” OR “Role of social media application to improve e-learning” OR “Challenges to implement e-learning programs” OR “Digital learning” AND “CPD” OR “Professional learning opportunities” OR “CPD” AND “Digital literacy” OR “Framework to design an e-learning system” OR “E-learning on social media platforms” OR “Digital learning” AND “online continuing education” OR “IT skills” AND “Effective CPD” OR “Career development” AND “Value-added library services” OR “Role of technology in growing e-learning” OR “Role of library leadership” AND “E-learning strategies” OR “E-learning for professional development” AND “Sustainable e-learning professional development” OR “Professional development model” AND “Effects of professional development” OR “Collaborative e-learning” OR “Challenges for implementing e-learning” OR “Key factors of CPD” OR “E-learning for practicing librarians” AND “CPD of in-service library professionals” OR “E-learning for librarians” AND “CPD for library professionals” OR “Role of transformative leadership for CPD” OR “Best practices to implement e-learning for CPD” OR “Online professional development” OR “Benefits and challenges for adopting e-learning” OR “e-learning for university library professionals” OR “Blended learning continuing professional development” OR “Quality e-learning professional development” OR “Online professional development in librarianship” OR “Librarians’ technological readiness for online professional development” OR “Distance educational professional development” OR “Methods to develop an effective online portfolio” OR “Transformational online professional development” OR “Barriers to e-learning” OR “Continuing professional education in librarianship”)

- NOT

- (“E-learning” NOT “Traditional learning methods”, “Impact of online learning” NOT “Conventional learning”, “E-learning for professional development” NOT “Syllabus based learning”, “e-modules for CPD” NOT “On site learning”).

2.1.2. Literature Resources and Existing Research

The research team used 16 databases systematically to conduct a comprehensive search. These databases were Scopus, EBSCO Host, Web of Science, ERIC, LISTA, Emerald, LISA, Summon, Elsevier, Google Scholar, Taylor & Francis, Pro-Quest, IEEE Xplore, Springer Link, Cambridge University Press, and Wiley Inter-Science. Articles published in peer-reviewed journals were accessed through digital databases. Papers published from 2002 to 2021 in impact factor journals were included in the study to conduct a systematic literature review (SLR).

2.2. Stage Two: Selection

- (1).

- Search process

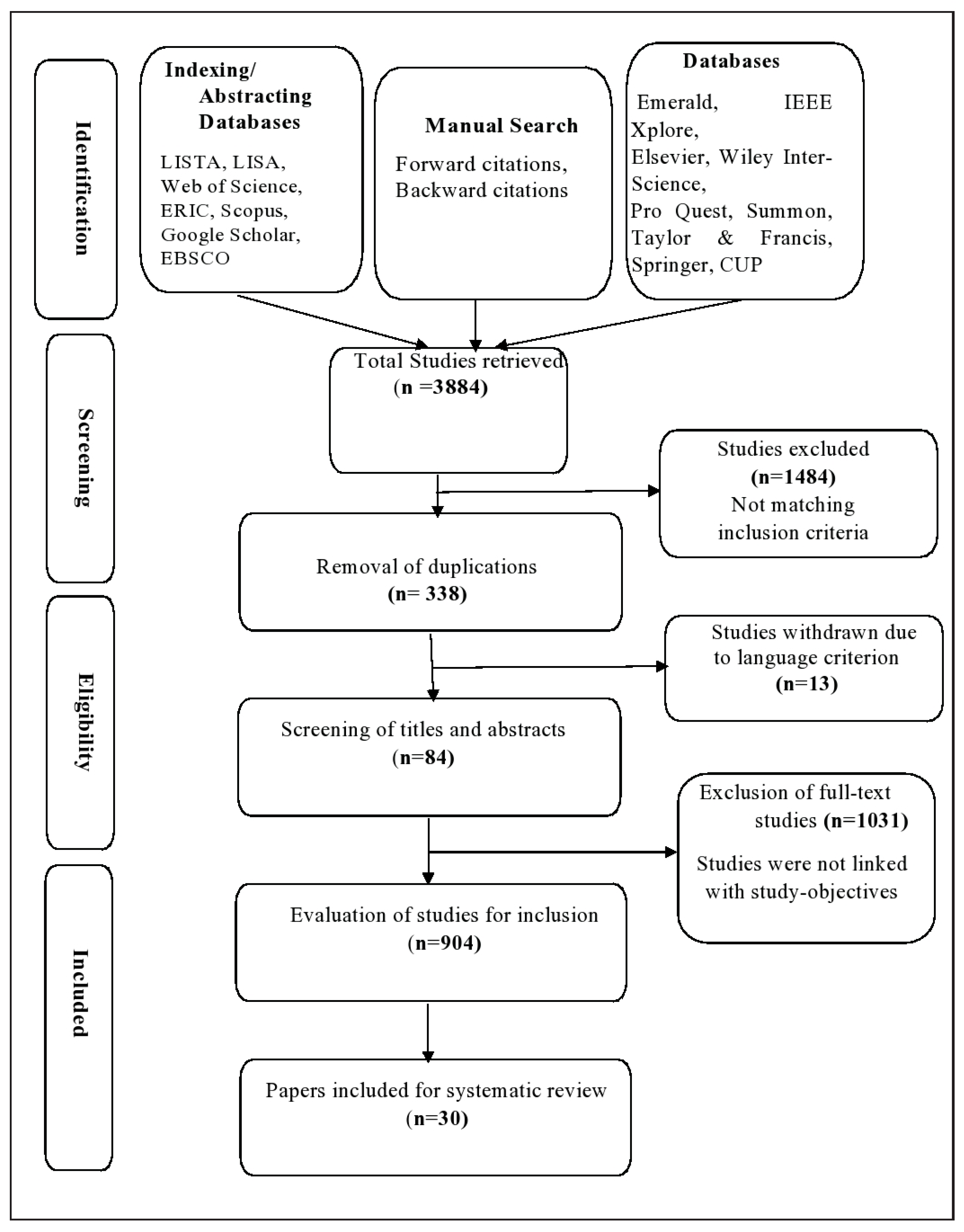

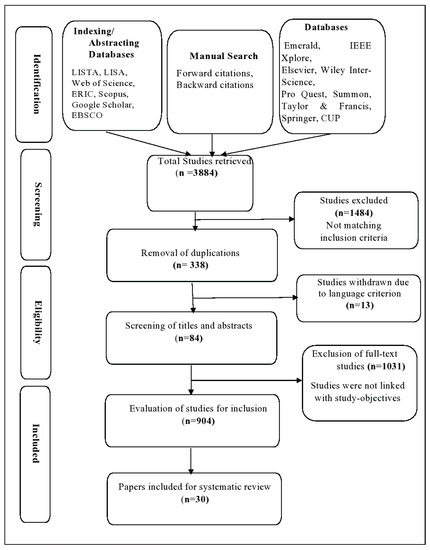

A comprehensive search is applied in a systematic literature review (SLR) for finding and locating available literature covering the pre-constructed research questions. Figure 1 displays different steps of the procedure.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the search process.

Step 1: Sixteen digital databases and tools were searched systematically for retrieving the results.

Step 2: Retrieved documents were scrutinized to include only relevant results. To check relevancy, titles of the articles were observed carefully. Papers published before 2002 were not included in the study. In total, 3884 results were retrieved. Through elimination, 1484 articles were excluded, and 338 articles were skipped after the exclusion of duplications. Through title and abstract screening, 84 studies were excluded from the list. Thirteen articles published in other languages than English were also withdrawn. After the evaluation of full-text studies, 904 papers were excluded, and 1031 irrelevant studies were also not included due to irrelevancy. The 30 most relevant peer-reviewed research articles published were selected to carry out the SLR.

- (2).

- Scrutiny and filtering

Initially retrieved documents (3884 as illustrated through Figure 1) from 16 different databases and tools were critically analyzed for ensuring relevancy. Multiple steps were carried out to complete the procedure. Various aspects including titles, language, type, content, diction, impact score, and publishing year were considered critically to include the most robust recently published studies in the current study for conducting a systematic review.

2.3. Stage Three: Extraction

According to the pre-developed research questions of the study, scorekeeping was allocated to the retrieved articles. Studies having relevancy with the set criteria were provided a score. This process led to the exclusion of 3854 irrelevant results and resulted in the retrieval of the 30 most relevant articles for addressing the present research questions.

2.4. Stage Four: Execution

The final step was to check validity and authenticity of the retrieved literature to ensure the quality of the work. Studies having no relevancy to e-learning and CPD were not included in the study. Conference proceedings, books, magazines, dissertations, newspaper articles, grey literature, organizational newsletters, magazine articles, reports, book chapters, presentations, standards, government documents, assignments, streaming videos, and trade publication articles were also not included. A final selection of 30 peer-reviewed research papers covering variables of the study were included to conduct the current study. Figure 1 offers a graphical illustration of the complete searching process conducted by the research team.

Table 1 illustrates the datasets extracted through 30 selected research papers. The table displays information about the authors, publishing years of the studies, place of the studies, journals in which the papers were published and information about the study’s objectives.

Table 1.

Datasets extracted via 30 research articles.

3. Findings

3.1. Geographical Distribution of the Studies

In systematic review, it is necessary to discover geographical locations of the selected articles. Results revealed that selected studies (n = 30) had been investigated in 16 dispersed regions of the world. Most of the studies on the topic had been conducted in the United States (n = 8). Table 2 displays geographical locations of the studies held on the e-learning for CPD of library professionals.

Table 2.

Geographical distribution of the studies (n = 30).

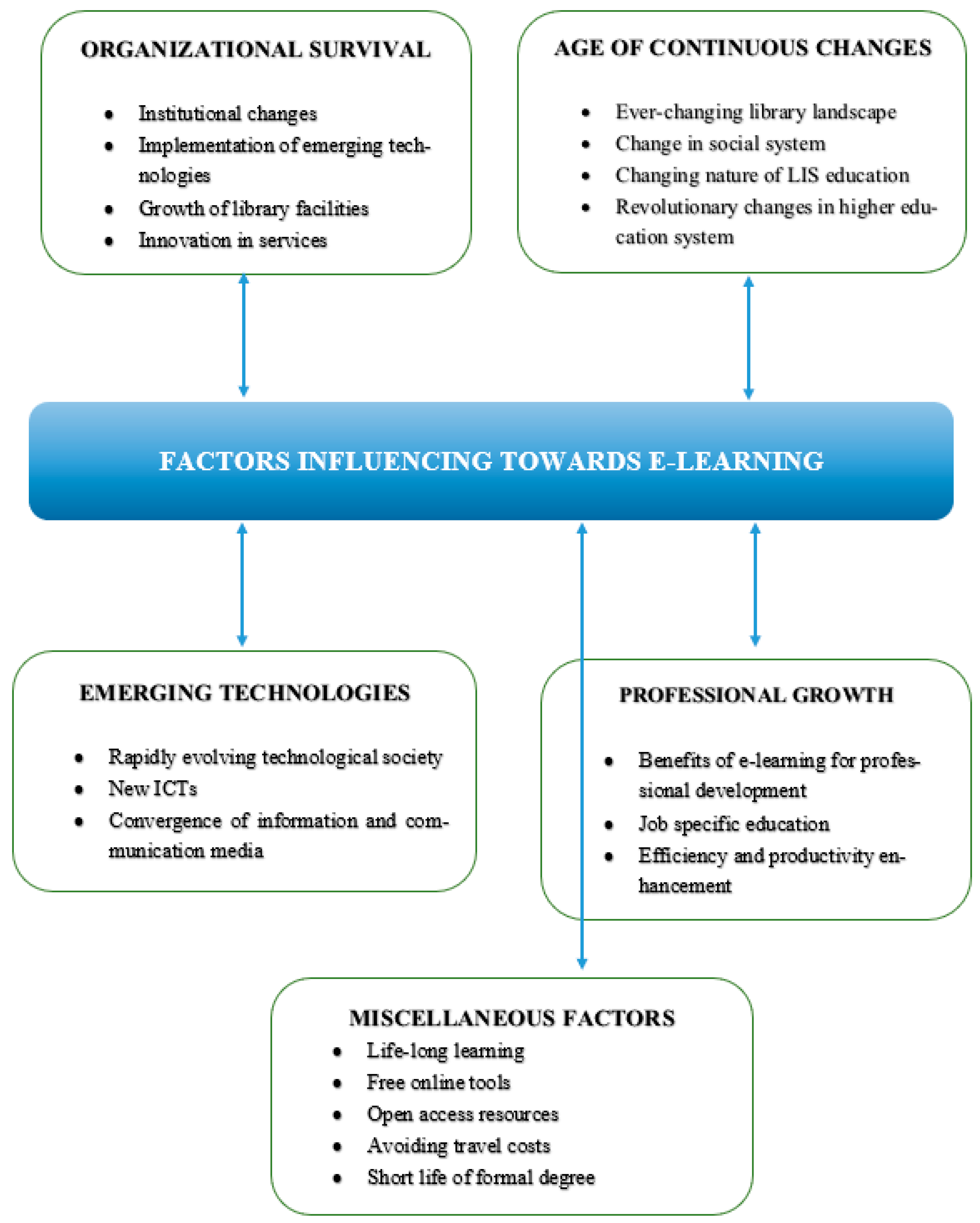

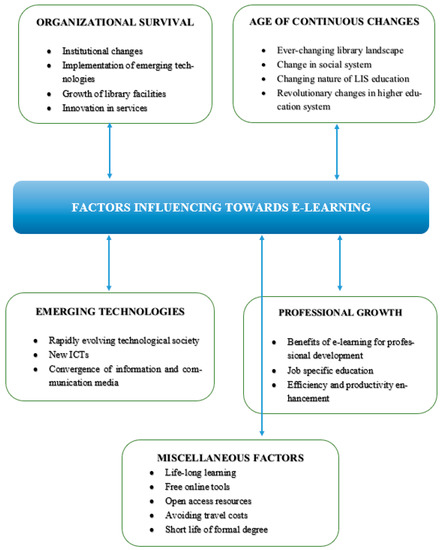

3.2. Factors Influencings E-Learning

Several factors attracted information professionals in carrying out services in university libraries towards e-learning for continued professional development (CPD). Factors are classified into the organizational survival, age of continuous changes, adoption of emerging technologies, professional growth, and miscellaneous factors and interpreted as follows.

3.3. Organizational Survival

Extracted data-sets displayed that e-learning for CPD was highly indispensable for organizational successes and survival because in the current era of continuous changes, organizational survival was not possible without the implementation of emerging technologies in the organization. Changes at the workplace stimulated information professionals to move towards e-learning courses for their professional growth [8] and addition to professional skills of the librarians proved valuable for the organizational survival [22]. Organizational survival was a key factor [35] that led towards the learning of new skills [8] for successfully managing institutional changes [19]. Growth of library facilities and innovation in services were not easy to be executed without e-learning for CPD [19,26].

3.4. Age of Continuous Changes

Ever-changing library landscape inspired employers and library professionals to adopt e-learning for CPD to meet changing situations effectively and efficiently [31,36]. Age of continuous changes attracted library manpower towards e-learning [25] for successfully managing changing work environments [35]. Changes in social system, constant changes in the field, changing nature of LIS education, and revolutionary changes in higher education system were all factors that urged decision-makers to offer e-learning opportunities to information professionals for their professional development to implement emerging technological tools in the universities to facilitate end users efficiently [8,9,14,31].

3.5. Adoption of Emerging Technologies

Rapidly evolving technological society was a pertinent factor to adopt e-learning for CPD of library professionals working in the universities [37]. Technological advancements were on the rise [9]; therefore, successful adoption of emerging technologies demanded skilled library professionals [35]. Continuing technological advances, rise of web 2.0 tools, convergence of information and communication media, and the application of new ICTs in the libraries influenced library professionals to take an active part in e-learning programs to keep pace with the changing technology and to grow their professional skills for successful adoption of emerging technologies in their libraries [19,29,38].

3.6. Professional Growth

E-learning improved professional knowledge and skills of the library workforce [19] and provided ample opportunities to develop skills in a variety of areas [39]. Job-specific education was provided to information professionals for their professional development so that they might re-shape information resources for the virtual community and advance in career and personal growth [24,26]. Subject knowledge was acquired through e-learning; efficiency and productivity were enhanced, and it was highly beneficial for librarians’ professional growth [29].

3.7. Miscellaneous Factors

Other factors influencing e-learning for CPD of university information professionals included life-long learning [35]; provision of free online tools [8]; free higher education to all [10]; affordability [23]; open access resources, information exchange, flexibility of hour, effectiveness, convenience [39]; 24/7 accessibility, virtual instructional activities, provision of life-long skills, e-learning via ubiquitous manner—anywhere, anytime, global accessibility, instantaneous educational opportunities [40]; extraordinary development of communication technologies [25]; short life of formal degree [11]; empowerment [41]; and saving of money, and avoiding travel costs [18].

Figure 2 reveals a broader outlook of factors influencing CPD through a graphical illustration.

Figure 2.

Factors influencings CPD.

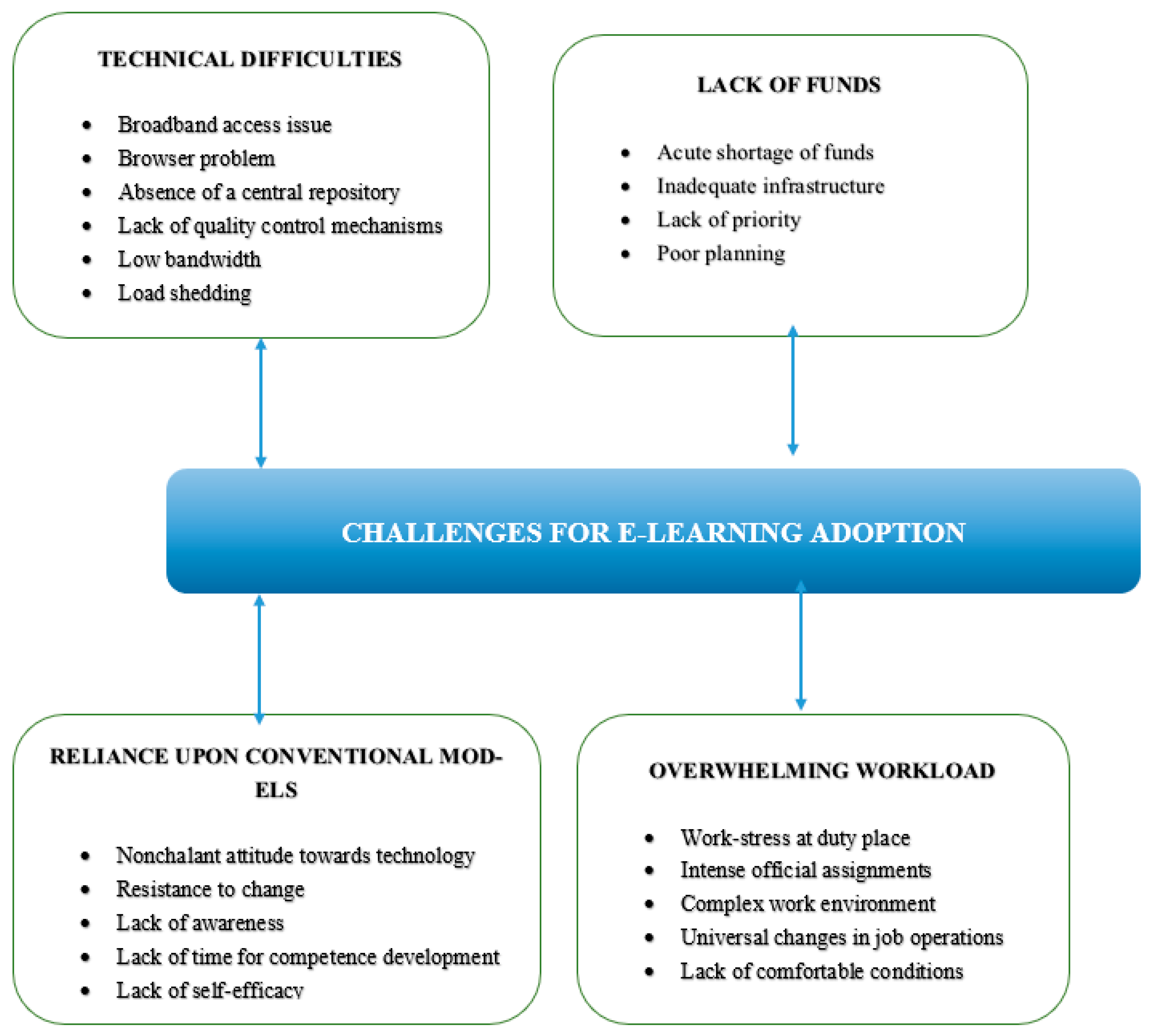

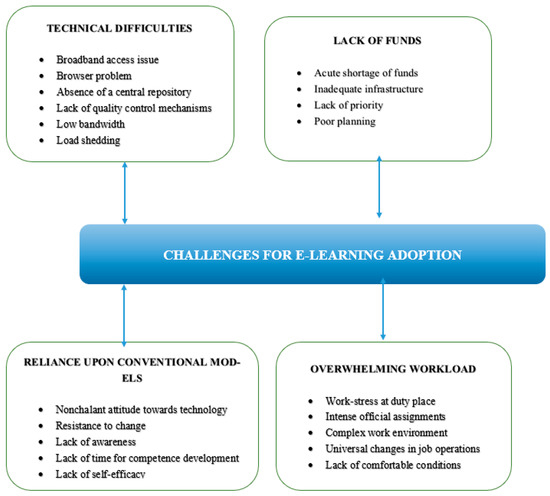

3.8. Challenges Encountered for E-Learning Adoption

Challenges being encountered for e-learning adoption for the CPD of university information professionals are grouped into technical difficulties, lack of funds, reliance upon conventional models, and overwhelming workload. These challenges are elaborated as follows alternately:

3.9. Technical Difficulties

Broadband access issue, browser problem, absence of a central repository, and lack of quality control mechanisms caused barriers for the successful adoption of e-learning programs for continued professional development of university librarians [3,8,35]. In addition, low bandwidth, technology’s explosive expansion, incessant power outage, and network failures created hurdles for the success of e-learning courses [18,25,37,39].

3.10. Lack of Funds

Acute shortage of funds, inadequate infrastructure, and lack of priority by the government and employers for the professional development of the information professionals via e-learning [14,35,39] created problems for turning manpower into skilled intellectual assets for the delivery of value-added outcomes at workplace.

3.11. Reliance upon Conventional Models

Nonchalant attitude towards technology, reliance upon conventional models, resistance to change, lack of awareness, lack of time for competence development, and lack of confidence in using new technologies caused failure in successful implementation of e-learning activities for the library workforce performing services in the universities [18,35,39].

3.12. Overwhelming Workload

Workplace stress, intense official assignments, hard office routine, overwhelming workload, complex work environment with diverse tasks, and universal changes in the job operations put constraint for the effective adoption of e-learning courses for the professional grooming of the early career information professionals [14,25,35].

Figure 3 illustrates graphically the challenges being encountered for e-learning adoption for the CPD of university information professionals.

Figure 3.

Challenges for e-learning adoption.

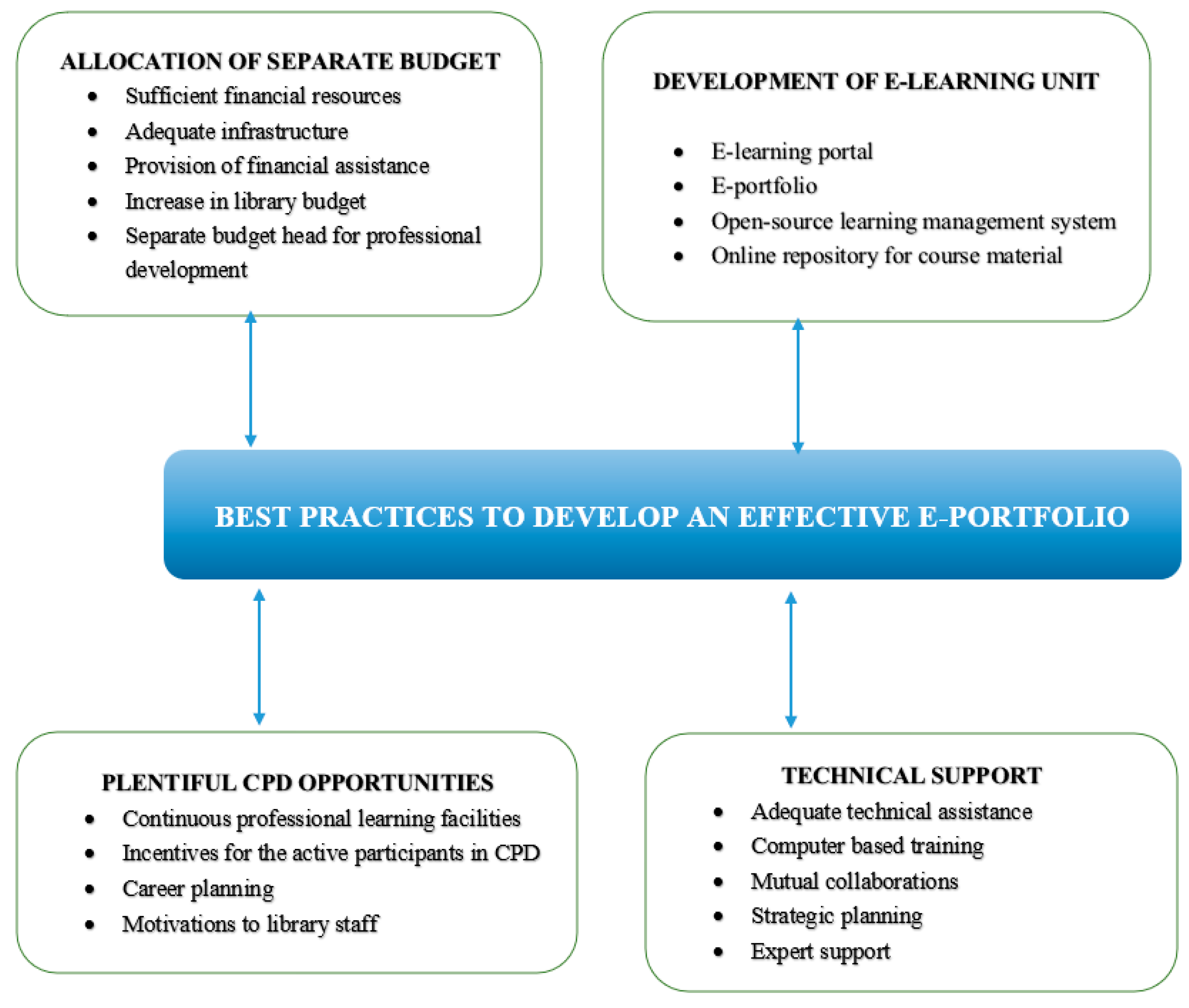

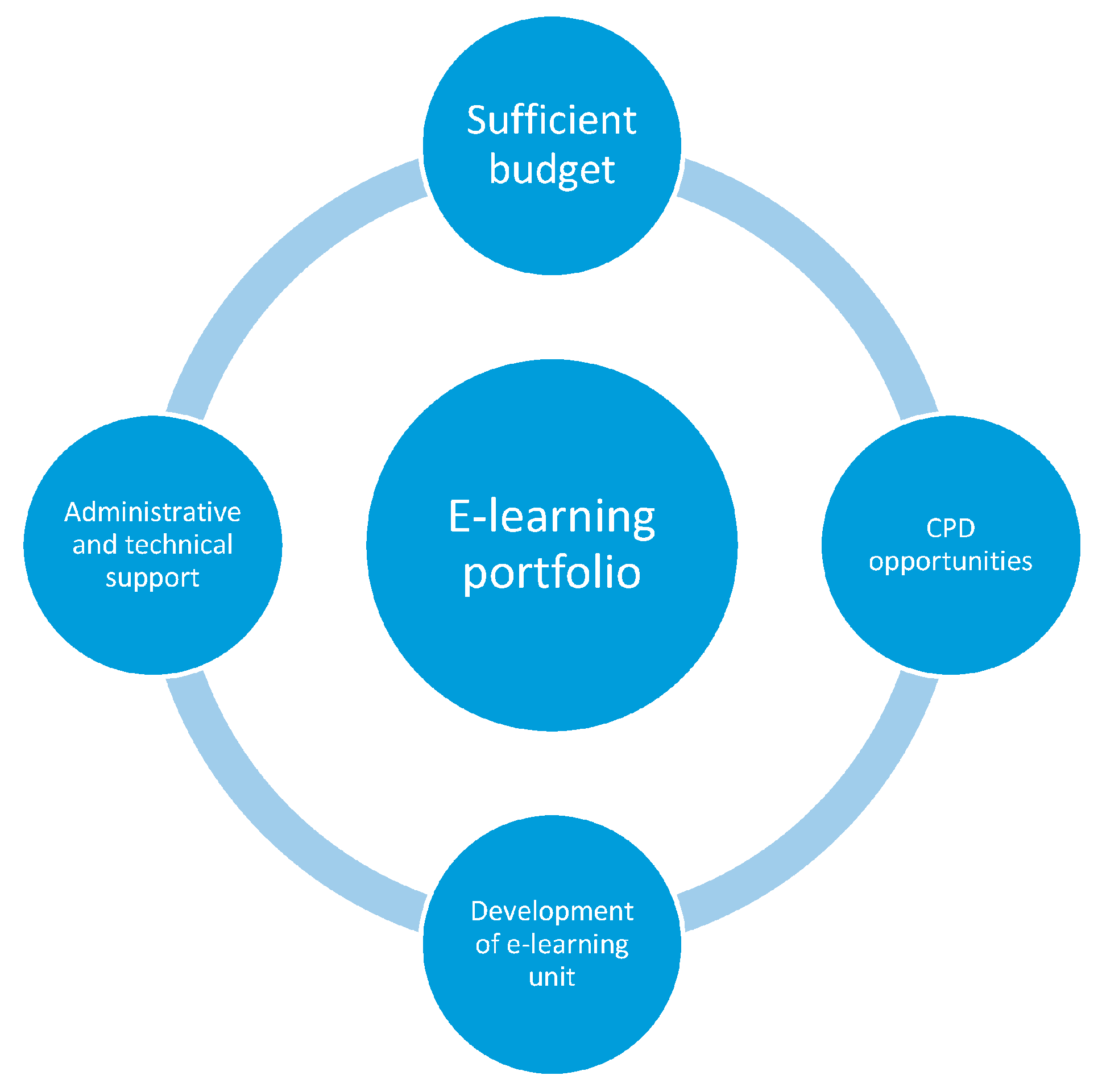

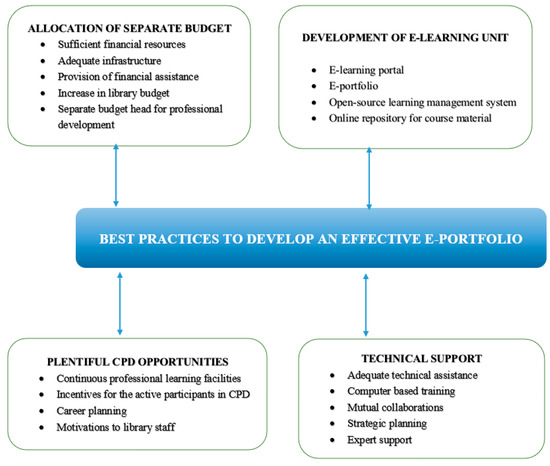

3.13. Best Practices to Develop an Effective E-Portfolio

Best practices to develop an affective e-portfolio for the delivery of e-learning for the CPD of information professionals are classified into allocation of separate budget, development of e-learning unit, plentiful professional learning opportunities, and technical support. These practices—inferred via selected studies—are interpreted as follows:

3.14. Allocation of Separate Budget

Allocation for separate budget encouraged library professionals to attend e-learning programs for their competence development [36]. Adequate infrastructure was a must for the success of e-learning activities for the transformation of information professionals [2]. Provision of sufficient funds enabled library professionals to develop technological skills for the provision of value-added services to facilitate the users through the implementation of trending technologies in the workplaces [5]. Financial assistance inspired library professionals [8] to attend short-term webinars enthusiastically [14]. There should be a positive attitude of all stakeholders [11] towards training of library professionals [42]. Library budget should be increased [31] for the creation of positive changes in librarians’ mindset [29].

3.15. Development of E-Learning Unit

An e-learning unit should be established [21] to provide adequate online learning environment [22]. E-learning portals [27] facilitated autonomous learning paths [22] in the digital environment. Implementation of an e-portfolio [23] ensured availability of relevant career development opportunities [37]. Open-source learning management system, and repository for course material [21] supported the usage of online asynchronous tools [22].

3.16. Plentiful Professional Learning Opportunities

Continuous professional learning opportunities, incentives for the active participants in CPD programs, value to the individuals, and financial support to workforce [22,30,36] helped to provide professional networking facilities, motivated staff, and created interest groups for professional discussions [2,14]. Discovery of individual talents, learning motivations to the professionals and incentives for potential learners [15] led library professionals to concentrate upon their competence development, personal career planning, and commitment of life-long learning [11,31]. Motivations to library workforce [29] created openness in library professionals towards new trends in the field and emotional training to play a leading role in the organization through effective participation in staff training events [26,41].

3.17. Technical Support

Technical support was of paramount significance [3] in the designing of effective learning modules [43] for e-community building [22]. Adequate technical assistance proved productive [21] in the making of an e-learning society [43]. Computer based training, web-based expertise, mutual collaboration, flexible systems, and strategic planning [27] proved valuable in developing online culture and knowledge communities [8]. Career guides, meaningful documentation, collaborative efforts, continuous assessment of e-learning courses, awareness sessions, support from peers and experts, and customized instruction [2,3,5,8,9,22,30] assisted in the successful training of information professionals via virtual workshops, and e-conferences [14,23]. Low-cost or no-cost options for career development, satisfaction survey at the end of e-learning programs, usage of social media platforms, effective plans, strategic leadership approach, supportive environment, involvement of professional associations in the delivery of technical skills, critical skills development, administrative encouragement to professional development, reflections and follow up activities in e-learning programs for the continued professional development of library workforce working in the university libraries impacted on the job-outcomes at workplace through the successful implementation of trending technologies [24,25,29,31,37,41,42].

Figure 4 displays the best practices for the development of an affective e-portfolio for the delivery of e-learning for the CPD of information professionals.

Figure 4.

Best practices to develop an effective e-portfolio.

4. Discussion

Results of the study showed different factors influencing the adoption of e-learning programs for continued professional development (CPD) of university library professionals. Survival of the organizations, continuous changes at workplaces, innovation in library services, ever-changing library landscape, changes in social system, revolutionary changes in higher education system, technological advancements, convergence of information and communication media, and job-specific education stimulated library professionals towards e-learning for CPD. Provision of free online tools, free higher education to all, open access resources, information exchange, effectiveness, convenience, accessibility, virtual instructional activities, provision of life-long skills, e-learning via ubiquitous manner—anywhere, anytime, global accessibility; instantaneous educational opportunities; extra ordinary development of communication technologies; and the short life of formal degree were key factors in attracting library professionals to e-learning programs for their sustainable competence development. These findings are similar to the results of the studies conducted by Gross and Leslie; Massis; Cassner and Adams; Ezeani et al.; Ahsan; Aslam; Attebury; Venturella and Breland; Sivankalai [9,14,19,25,26,29,31,35,38].

The second objective of the research was to find out challenges being encountered for the adoption of e-learning programs for CPD of library professionals carrying out services in university libraries. The study revealed several challenges that were faced in the successful implementation of online courses for the professional development of library manpower. Absence of a central repository, broadband access issues, lack of quality control mechanisms, technology’s explosive expansion, incessant power outages, network failures, funding shortage, reliance upon conventional styles, lack of awareness, lack of time for competence development, and work load all created barriers to adopt online professional learning courses to equip manpower with innovative learning and expertise to implement the latest services to facilitate the users. These findings are related to the study-results investigated by Klein and Ware; Cooke; Anasi and Ali; Hendrix and McKeal; Anene [3,8,11,18,39].

The aim of third goal was to offer the best practices to design an efficient e-learning portfolio. Study results revealed that allocation for separate budget, adequate infrastructure, positive attitude of all stakeholders, establishment of an e-learning unit, online learning portal, self-direction in e-learning, open-source learning management system, repository for course material, usage of online asynchronous tools, and plentiful professional learning opportunities were key practices encouraging successful functioning of e-learning programs for CPD of information professionals. Additionally, technical support, e-community building, strategic planning, computer-assisted training, web-based expertise, mutual collaboration, career guides, meaningful documentation, usage of social media platforms, effective plans, strategic leadership approach, supportive environment, involvement of professional associations in the delivery of technical skills, critical skills development, and administrative encouragement to professional development were also the key practices that played a vital role in the successful adoption and sustainability of e-learning programs for CPD of library human resources. These results are in consonance with the findings of the studies conducted by Klein and Ware; Rossi et al.; Massis; Stein; Fourie; Khan and Du; Chang and Hosein; Attebury; Venturella and Breland; Namaganda [2,3,5,9,22,24,29,31,41].

This study has proposed a framework (Figure 5) consisted of trending practices and practical steps for the successful adoption, functioning, and sustainability of e-learning programs for continued professional development of university library professionals for the delivery of users’ centered services through the implementation of emerging technologies. Extracted data via 30 studies (Table 1) have presented a comprehensive picture of the best practices for the adoption of e-learning portfolio to develop professional expertise in library professionals for efficient job outcomes. The framework displays practical solutions for the employers to work on the sustained competence development of information professionals through successful implementation of e-learning programs so that target users may be aided effectively.

Figure 5.

Framework for the establishment of an efficient e-learning portfolio for CPD of library professionals.

The framework (Figure 5) is highly productive for administrative heads, decision-makers, policymakers, higher education departments, chief librarians, employers, government representatives, and the funders for taking necessary initiatives in the adoption of sustainable e-learning programs for CPD of university library professionals to meet organizational objectives. A centralized e-learning portal based upon the constructed model having uniform policies and procedures may be developed for the provision of quality learning and required expertise.

The study has also shown that certain noticeable challenges are encountered in the successful adoption and functioning of e-learning programs for the CPD of information professionals; nevertheless, transformative leadership might play a key role in overcoming core barriers for the successful adoption of e-learning for the professional development of information professionals working in the university libraries through the initiation of revolutionary steps to uplift the organization by turning manpower into skilled intellectual asset.

5. Conclusions

It is clear in light of the study’s findings that, in the current age, technology rules due to rapid changes in all fields of life—especially electronic-based-learning. Therefore, it is necessary for not only survival in the field, but also to sustain value-added output in the workplace. Professionally skilled and groomed library professionals play a vital role in implementing all effective measures to satisfy information and research needs of the end users having used artificial intelligence (AI) powered tools as per changing trends in service-delivery methods. To equip the university library professionals with the quality e-learning for CPD, administrative support is highly necessary, otherwise staff may become demotivated and organizational goals may not be achieved efficiently.

6. Limitations

The authors searched literature through online databases to conduct SLR. Literature was not explored via institutional repositories, search engines, blog posts, Lib Guides, etc. The research team only included peer-reviewed research papers (n = 30) to conduct the systematic literature review. Other sources of knowledge—such as conference proceedings, books, newspaper columns, articles from magazines, grey literature, review reports, and dissertations—were not included. Although serious efforts were made by all research team members to search all existing core studies on the topic, some potential studies may be have been missed from the worldwide published literature. Articles not published in the English language were not included in the study.

7. Future Research Directions

- This study looked at the role of e-learning for CPD of university librarians through a systematic literature review methodology. Future authors may conduct similar studies on the same topic through quantitative or qualitative or mixed methods.

- Future authors may include blogs, websites, grey literature, dissertations, conference proceedings, and books to conduct a systematic literature review on the effects of e-learning on the sustainable competence development of academic librarians.

- Future researchers may include all types of librarians, including college librarians and medical librarians, to identify the role of e-learning upon their professional development.

- Future investigators may conduct the role of e-learning on CPD using different adult learning theories through empirical methods.

- A quantitative study may also be conducted by future authors for testing the validity of the framework offered through the current study for the establishment of an efficient e-learning portfolio for CPD of library professionals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S., S.A.K. and Y.J.; methodology, S.A.K. and Y.J.; validation, K.S. and A.I.: formal analysis, K.S. and A.I.; investigation, K.S., S.A.K., Y.J. and A.I.; resources, Y.J. and A.I.; data curation, Y.J. and A.I.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S., S.A.K., Y.J. and A.I.; writing—review and editing, K.S. and A.I.; visualization, K.S. and A.I.; supervision, S.A.K. and Y.J.; project administration, S.A.K., and Y.J.; funding acquisition, Y.J. and A.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was received however financial assistance was provided by Prince Sultan University Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for the provision of APC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The research team acknowledges the assistance of Prince Sultan University Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for the provision of APC.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bhabal, J. E-learning in LIS education: Case study of SHPT school of library science. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference CALIBER-2008, University of Allahabad, Allahabad, India, 28–29 February & 1 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- SStein, S.J.; Shephard, K.; Harris, I. Conceptions of e-learning and professional development for e-learning held by tertiary educators in New Zealand. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2009, 42, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D.; Ware, M. E-learning: New opportunities in continuing professional development. Learn. Publ. 2003, 16, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, B.M.; Hassan, B.B. Strategies for Developing an e-Learning Curriculum for Library and Information Sciences (LIS) Schools in the Muslim World: Meeting the Expectations in the Digital Age. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2013, 3, 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Fourie, I. Twenty-first century librarians: Time for Zones of Intervention and Zones of Proximal Development? Libr. Hi Tech 2013, 31, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hedberg, J.; Ping, L.C. Charting trends for e-learning in Asian schools. Distance Educ. 2004, 25, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slebodnik, M.; Riehle, C.F. Creating Online Tutorials at Your Libraries: Software Choices and Practical Implications. Ref. User Serv. Q. 2009, 49, 33–37, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, N.A. Professional development 2.0 for librarians: Developing an online personal learning network (PLN). Libr. Hi Tech News 2012, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Massis, B.E. Continuing professional education: Ensuring librarian engagement. New Libr. World 2010, 111, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecclestone, M. MOOCs as a Professional Development Tool for Librarians. Partnersh. Can. J. Libr. Inf. Pract. Res. 2013, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, B.R.; McKeal, A.E. Case Study: Online Continuing Education for New Librarians. J. Libr. Inf. Serv. Distance Learn. 2017, 11, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiffe, D.J. Webinars: Continuing Education and Professional Development for Librarians. J. Leadersh. Manag. Sect. 2012, 9, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, A.M. Wired Professional Development: New Librarians Connect Through the Web. Coll. Undergrad. Libr. 2008, 14, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassner, M.; Adams, K.E. Continuing Education for Distance Librarians. J. Libr. Inf. Serv. Distance Learn. 2012, 6, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, A.E.C. Librarians’ Leadership for Lifelong Learning. Public Libr. Q. 2012, 31, 91–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igben, M.J.; Akobo, D.I. State of information and communication technology (ICT) in libraries in Rivers State, Nigeria. African J. Libr. Arch. Inf. Sci. 2007, 17, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Nebeolise, L.N. The Impact of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Compliant Librarians on Library Services Delivery in Academic Library: The Case of National Open University of Nigeria (Noun) Library. Int. J. Educ. Benchmark 2018, 10, 118–129. [Google Scholar]

- Anene, I.A.; Idiedo, V.O. Librarians participation in professional development workshops using Zoom in Nigeria. Inf. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeani, C.N.; Eke, H.N.; Ugwu, F. Professionalism in library and information science. Electron. Libr. 2015, 33, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiser, B.E. Professional Development and Continuing Education. Online 2012, 36, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Fontanin, M. Developing an English course for in-service librarians. Libr. Manag. 2008, 29, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.G.; Magnoler, P.; Giannandrea, L. From an e-portfolio model to e-portfolio practices: Some guidelines. Campus-Wide Inf. Syst. 2008, 25, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampe, N.; Lewis, S. E-portfolios support continuing professional development for librarians. Aust. Libr. J. 2013, 62, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Du, J.T. Professional development through social media applications: A study of female librarians in Pakistan. Inf. Learn. Sci. 2017, 118, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M. Professional Development and Networking for Academic Librarians. Int. Res. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sivankalai, S. Academic libraries support e-learning and lifelong learning: A case study. Libr. Philos. Pract. 2021, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sammour, G.; Schreurs, J.; Al Zoubi, A.Y.; Vanhoof, K. The role of knowledge management and e-learning in professional development. Int. J. Knowl. Learn. 2008, 4, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlejs, J. IFLA Guidelines for Continuing Professional Development: Principles and Best Practices; IFLA: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Venturella, K.; Breland, M. Supporting the best: Professional development in academic libraries. J. New Librariansh. 2019, 4, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.C.; Auster, E. Factors contributing to the professional development of reference librarians. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2003, 25, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attebury, R. The Role of Administrators in Professional Development: Considerations for Facilitating Learning Among Academic Librarians. J. Libr. Adm. 2018, 58, 407–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.; Leslie, L. Twenty-three steps to learning Web 2.0 technologies in an academic library. Electron. Libr. 2008, 26, 790–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ai-Ling, Y. Continuous professional development for librarians. J. Persat. Pustak. Malaysia 2009, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, S.; Shorish, Y.; Whitmire, A.L.; Hswe, P. Building professional development opportunities in data services for academic librarians. IFLA J. 2017, 43, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A. Analysis of training initiatives undertaken for professional development of library professionals in Pakistan. Libr. Philos. Pract. 2014, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Anasi, S.N.; Ali, H. Academic librarians’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of adopting e-learning for continuing professional development in Lagos state, Nigeria. New Libr. World 2014, 115, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.E.; Taylor, D.M. The role of the academic Library Information Specialist (LIS) in teaching and learning in the 21st century. Inf. Discov. Deliv. 2017, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namaganda, A. Continuing professional development as transformational learning: A case study. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2020, 46, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen-Chang, P.; Hosein, Y. Continuing professional development of academic librarians in Trinidad and Tobago. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2019, 68, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, K.; Francis, S.; Tedd, L.A.; Tetrevova, M.; Zihlavnikova, E. Training for professional librarians in Slovakia by distance-learning methods: An overview of the PROLIB and EDULIB projects. Libr. Hi Tech 2002, 20, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).