The Configuration Effect of Institutional Environment, Organizational Slack Resources, and Managerial Perceptions on the Corporate Water Responsibility of Small- and Medium-Sized Corporations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

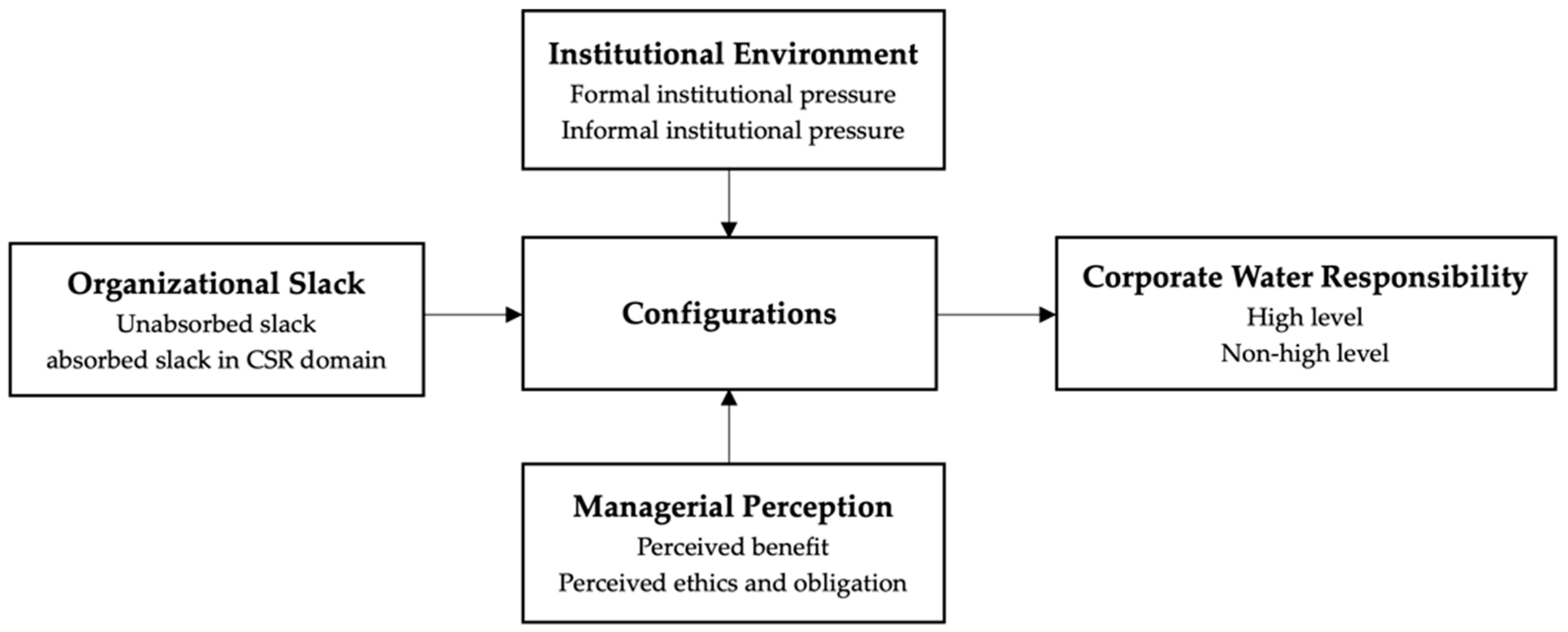

2. Theoretical Foundation and Research Model

2.1. What Is Corporate Water Responsibility?

2.2. Institutional Environment and Corporate Water Responsibility

2.3. Organizational Slack Resources and Corporate Water Responsibility

2.4. Managerial Perception and Corporate Water Responsibility

2.5. Research Model

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Methods

3.2. Samples

3.3. The Measurement of Variables and Fuzzy-Set Calibration

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Test

4.2. Necessary Conditions for High CWR

4.3. Configuration Effect Analysis

4.3.1. Configuration Leading to a High Level of CWR

4.3.2. Configuration Restricting a High Level of CWR

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Discussion

5.3. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Item |

|---|---|

| Formal institutional pressure | Our corporate water responsibility is greatly influenced by regulations posed by government agencies. |

| Legislation in water-related fields can affect the continued growth of our firm. | |

| Several penalties have been imposed on firms that violate water standards and regulations. | |

| Stricter water regulation and surveillance are major reasons why our firm is concerned about the impact on water. | |

| Our industrial cluster is faced with strict water regulations and surveillance. | |

| Informal institutional pressure | The increasing water consciousness of consumers has spurred our firm to implement corporate water responsibility. |

| Being water responsible is a basic requirement for our firm to be part of this industry. | |

| Being water responsible is a basic requirement for our firm to be part of the supply chain. | |

| Nongovernmental organizations around our firm expect us to implement corporate water responsibility. | |

| Stakeholders may not support our firm if our firm does not implement corporate water responsibility. | |

| Perceived benefits | The implementation of corporate water responsibility is useful to reduce our firm’s environmental cost and environmental impacts and thus enhance the firm image. |

| The implementation of corporate water responsibility is beneficial to increase our firm’s competitiveness and legitimacy. | |

| Reducing the water impact of our firm’s activities will lead to quality improvements in our products and processes. | |

| Our firm can increase its market share by making our current products more water friendly. | |

| The implementation of corporate water responsibility can help reduce our firm’s operational costs and identify new opportunities. | |

| Perceived ethics and obligation | The adoption of corporate water responsibility is an ethical obligation. |

| When deciding on corporate water responsibility, it is important to study considerations beyond the financial aspect. | |

| When implementing corporate water responsibility, it is personally important for me to think beyond the financial aspect. | |

| I have an ethical obligation to corporate water responsibility where I am a manager. | |

| Unabsorbed slack | Unused resources are available to support strategic initiatives in a short period of time in our firm. |

| There are plenty of resources available to support initiatives in the short term. | |

| Our firm could acquire resources to support new strategic initiatives in the short term. | |

| Absorbed slack in CSR | Our firm has invested above-average resources in our industry to fulfill social and environmental responsibilities. |

| The performance of our corporate social and environmental responsibility has exceeded social expectations. | |

| The resources invested in social and environmental responsibility need further utilization. | |

| Corporate Water Responsibility | Our firm has established and strictly implemented water management strategies and policies. |

| Our firm is fully aware of water risks and the nexus between water and other environmental issues. | |

| Our firm has pushed hard to reuse, recycle, and exploit unconventional water; thus, the efficiency of water utilization has reached above the average in our industry. | |

| Our firm attaches great importance to technological innovation and capital investment in water-saving and anti-water-contamination activities. | |

| Our firm conducts social publicity on the theme of water resource protection or invests long-term funds in public welfare projects in the field of water resource protection. | |

| Water responsibility is an important factor in our selection of suppliers, and we also inform our customers of our water responsibility. |

References

- World Meteorological Organization. State of Global Water Resources 2021; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report 2016; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wessman, H.; Salmi, O.; Kohl, J.; Kinnunen, P.; Saarivuori, E.; Mroueh, U.-M. Water and society: Mutual challenges for eco-efficient and socially acceptable mining in Finland. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 84, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello, E. From Risks to Shared Value? Corporate Strategies in Building a Global Water. Accounting and Disclosure Regime. Water Altern. 2013, 5, 636–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Ye, L.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H. Does Water Matter? The Impact of Water Vulnerability on Corporate Financial Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northey, S.A.; Mudd, G.M.; Werner, T.T.; Haque, N.; Yellishetty, M. Sustainable water management and improved corporate reporting in mining. Water Resour. Ind. 2019, 21, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, C.A. BHP mine water management: An integrated approach to manage risk and optimise resource value. In Slope Stability 2020, Proceedings of the 2020 International Symposium on Slope Stability in Open Pit Mining and Civil Engineering, Perth, Australia, 12–14 May 2020; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Perth, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bulcke, P.; Vionnet, S.; Vousvouras, C.; Weder, G. Nestlé’s corporate water strategy over time: A backward- and forward-looking view. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2020, 36, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burritt, R.L.; Christ, K.L. The need for monetary information within corporate water accounting. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 201, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.H.; Shapiro, D.; Ho, S.H.; Shin, J. Location matters: Valuing firm-specific nonmarket risk in the global mining industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 1210–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.H.; Habibullan, M.S.; Tan, S.K.; Choon, S.W. The impact of the dimensions of environmental performance on firm performance in travel and tourism industry. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 203, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, G.; Cooper, W.H. Ecological Sensemaking. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Batres, L.A.; Doh, J.P.; Miller, V.V.; Pisani, M.J. Stakeholder Pressures as. Determinants of CSR Strategic Choice: Why do Firms Choose Symbolic Versus Substantive Self-Regulatory Codes of Conduct? J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, F.E.; Bansal, P.; Slawinski, N. Scale matters: The scale of environmental issues in corporate collective actions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 1411–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingey-Holyoak, J. Sustainable water storage by agricultural businesses: Strategic responses to institutional pressures. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2590–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, A.P.; Setiawan, D. Water disclosure in the agriculture industry: Does stakeholder influence matter? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, M.; Jin, Y.; Zeng, H. Does China’s river chief policy improve corporate water disclosure? A quasi-natural experimental. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, K.L. Water management accounting and the wine supply chain: Empirical evidence from Australia. Br. Account. Rev. 2014, 46, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Grable, K.; Hustvedt, G.; Ahn, M. Sustainable water consumption: The perspective of hispanic consumers. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 50, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. Water stewardship and corporate sustainability: A case study of reputation management in the food and drinks industry. J. Public Aff. 2015, 15, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burritt, R.L.; Christ, K.L.; Omori, A. Drivers of corporate water-related disclosure: Evidence from Japan. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O.; Saunders-Hogberg, G. Corporate social responsibility, water management, and financial performance in the food and beverage industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1937–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, M. Driving Water Management Change Where Economic Incentive is Limited. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, Q. Corporate Water Responsibility systems and incentives to self-discipline. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2019, 10, 592–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, Q.; Huang, R.H. Mind the Gap: Is Water Disclosure a Missing Component of Corporate Social Responsibility? Br. Account. Rev. 2021, 53, 100940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, M. Water usage reduction and CSR committees: Taiwan evidence. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 30, 1070–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, E. Towards Adaptation of Water Resource Systems to Climatic and Socio-Economic Change. Water Resour. Manag. 2017, 31, 2965–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Amar, W.; Chelli, M. What drives voluntary corporate water disclosures? The effect of country-level institutions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1609–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otras, E.; Burritt, R.L.; Christ, K.L. The influence of macro factors on Corporate Water Responsibility: A multi-country quantile regression approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Framework of Corporate Water Responsibility. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Gu, J.; Liu, H. Interactive effects of various institutional pressures on corporate environmental responsibility: Institutional theory and multilevel analysis. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 724–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, A.X.; Zhou, K.Z.; Jiang, W. Environmental Strategy, Institutional Force, and Innovation Capability: A Managerial Cognition Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnari, S.; Crilly, D.; Misangyi, V.F.; Greckhamer, T.; Fiss, P.C.; Ruth, V. Aguilera Capturing causal complexity: Heuristics for configurational theorizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2020, 46, 778–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, K.; Aviad, B. Multilevel corporate environmental responsibility. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Jia, L. Configuration Perspective and Qualitative Comparative Analysis: A New Way of Management Research. Manag. World 2017, 6, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambooy, T. Corporate social responsibility: Sustainable water use. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 852–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, R.; Peng, N.; Bowen, F. The Wealth Effect of Corporate Water Actions: How Past Corporate Responsibility and Irresponsibility Influence Stock Market Reactions. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvarioniene, J.; Stasiskiene, Z. Integrated water resource management model for process industry in Lithuania. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Hubbard, M.; Zhang, T.; Chen, L. Water stewardship in agricultural supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1170–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarni, W. Corporate Water Strategies; Earthscan: London, UK, 2011; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.S.; de Jong, M.; Levy, D.L. Building institutions based on information disclosure: Lessons from GRI’s sustainability reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.; Powell, W.W. The iron age revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Orginizations: Ideal, Interests, and Identities; Sage Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fini, R.; Toschi, L. Academic logic and corporate entrepreneurial intentions: A study of the interaction between cognitive and institutional factors in new firms. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 76, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. A transaction cost theory of politics. J. Theor. Politics 1990, 4, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Kong, D. The real effect of legal institutions: Environmental courts and firm environmental protection expenditure. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2019, 98, 102254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yu, N.Z.; Wan, H. Does water rights trading affect corporate investment? The role of resource allocation and risk mitigation channels. Econ. Model. 2022, 117, 106063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Lins, K.V.; Roth, L.; Wagner, H.F. Do institutional investors drive corporate social responsibility? International evidence. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 131, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivazidou, E.; Tsolakis, N.; Vlachos, D.; Iakovou, E. A water footprint management framework for supply chains under green market behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 592–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, J.; Zeng, H. Impact of product market competition on corporate water information disclosure: Based on the empirical evidence of China’s high water sensitivity Industry from 2010 to 2016. J. Bus. Econ. 2019, 11, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilsbach, L.; Schutte, P.; Franken, G. Water reporting in mining: Are corporates losing sight of stakeholder interests? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 343, 131016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlos, C.S.; Stelios, Z.; Naomi, A.G. Corporate environmental performance: Revisiting the role of organizational slack. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G. Slack resources and the performance of privately held firms. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, F.S.; Kehoe, R.R. Give Them Some Slack—They’re Trying to Change! The Benefits of Excess Cash, Excess Employees, and Increased Human Capital in the Strategic Change Context. Acad. Manag. J. 2020, 63, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, P.S.; Gerrit, W.; Richard, B.C.; David, A.T. Antecedents of Organizational Slack. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Li, J. The Dynamic Test of Iron Law of Responsibility: Empirical Evidence from the M&A Samples of Chinese Listed Companies. J. Manag. World 2018, 34, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiz, L.; Ferron-Vilchez, V.; Aragon-Correa, J.A. Do firms’ slack resources influence the relationship between focused environmental innovations and financial performance? more is not always better. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 1215–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Mousa, F.T. The implications of slack heterogeneity for the slack-resources and CSP relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 62, 5964–5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.G.; Delmastro, M. The determinants of organizational change and structural inertia: Technological and organizational factors. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2002, 11, 595–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormiston, M.E.; Wong, E.M. License to ill: The effects of corporate social responsibility and CEO moral identity on corporate social irresponsibility. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 861–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C. Upper echelons theory: An update. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Managerial Interpretations and Organizational Context as Predictors of Corporate Choice of Environmental Strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Hoejmose, S.; Marchant, K. Environmental management in SMEs in the UK: Practices, pressures and perceived benefits. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Liu, Y. Behind eco-innovation: Managerial environmental awareness and external resource acquisition. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Yadav, M. Environmental capabilities, proactive environmental strategy and competitive advantage: A natural-resource-based view of firms operating in India. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 291, 125249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelson, C. Compliance and the illusion of ethical progress. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 66, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandve, A.; Øgaard, T. Exploring the interaction between perceived ethical obligation and subjective norms, and their influence on CSR-related choices. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, R.; Akhter, J.; Malarvizhi, P. Managers’ perception on factors impacting environmental disclosure. J. Manag. 2019, 6, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, G.B.; Sirdeshmukh, D.; Voss, Z.G. The Effects of Slack Resources and Environmental Threat on Product Exploration and Exploitation. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Beamish, P.W.; Jackson, S.E.; Mathieu, J.E. Building theoretical and empirical bridges across levels: Multilevel research in management. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1385–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G. Moving beyond multiple regression analysis to algorithms: Calling for adoption of a paradigm shift from symmetric to asymmetric thinking in data analysis and crafting theory. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misangyi, V.F.; Greckhamer, T.; Furnari, S.; Fiss, P.C.; Crilly, D.; Aguilera, R. Embracing Causal Complexity: The Emergence of a Neo-Configuration Perspective. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misangyi, V.F.; Acharya, A.G. Substitutes or Complements? A Configurational Examination of Corporate Governance Mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1681–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, J. Exploring the effects of institutional pressures on the implementation of environmental management accounting: Do top management support and perceived benefit work? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troilo, G.; De Luca, L.M.; Atuahene-Gima, K. More innovation with less? A strategic contingency view of slack resources, information search, and radical innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Verdú, F.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Roig-Tierno, N. Firm survival: The role of incubators and business characteristics. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 793–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cronbach’s α Coefficient | KMO 1 | Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Factor Loading Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal institutional pressure | 0.842 | 0.813 | 0.000 < 0.001 | 0.732~0.854 |

| Informal institutional pressure | 0.820 | 0.811 | 0.695~0.820 | |

| Unabsorbed slack | 0.865 | 0.832 | 0.743~0.878 | |

| Absorbed slack in CSR | 0.823 | 0.810 | 0.722~0.897 | |

| Perceived benefits | 0.845 | 0.832 | 0.755~0.877 | |

| Perceived ethics and obligation | 0.858 | 0.831 | 0.719~0.860 | |

| Corporate water responsibility | 0.876 | 0.844 | 0.766~0.876 |

| Condition | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|

| High Level of CWR | Non-High Level of CWR | |

| Formal institutional environment | 0.678 | 0.475 |

| ~Formal institutional environment | 0.427 | 0.763 |

| Informal institutional environment | 0.812 | 0.522 |

| ~Informal institutional environment | 0.465 | 0.799 |

| Unabsorbed slack | 0.757 | 0.611 |

| ~Unabsorbed slack | 0.473 | 0.764 |

| Absorbed slack in CSR | 0.716 | 0.483 |

| ~Absorbed slack in CSR | 0.481 | 0.750 |

| Perceived economic benefit | 0.782 | 0.463 |

| ~Perceived economic benefit | 0.401 | 0.930 |

| Perceived ethics and obligation | 0.923 | 0.534 |

| ~Perceived ethics and obligation | 0.409 | 0.737 |

| Condition | High Level of CWR | Non-High Level of CWR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | H2 | H3 | L1 | L2 | |

| Formal institutional environment | ● | ⊗ | ⊗ | ||

| Informal institutional environment | ● | ● | ⊗ | ⊗ | |

| Unabsorbed slack | ● | ● | ⊗ | ||

| Absorbed slack in CSR | ⊗ | ● | ● | ||

| Perceived economic benefit | ● | • | ⊗ | ⊗ | |

| Perceived ethics and obligation | • | • | ● | ||

| Coverage | 0.534 | 0.621 | 0.367 | 0.436 | 0.335 |

| Net Coverage | 0.061 | 0.056 | 0.037 | 0.052 | 0.036 |

| Consistency | 0.881 | 0.855 | 0.879 | 0.871 | 0.865 |

| Overall Coverage | 0.705 | 0.528 | |||

| Overall Consistency | 0.823 | 0.861 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, J.; Zheng, L.; Cheng, C.; Wang, M. The Configuration Effect of Institutional Environment, Organizational Slack Resources, and Managerial Perceptions on the Corporate Water Responsibility of Small- and Medium-Sized Corporations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107821

Gu J, Zheng L, Cheng C, Wang M. The Configuration Effect of Institutional Environment, Organizational Slack Resources, and Managerial Perceptions on the Corporate Water Responsibility of Small- and Medium-Sized Corporations. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):7821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107821

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Jiahao, Liyuan Zheng, Changgao Cheng, and Mengjiao Wang. 2023. "The Configuration Effect of Institutional Environment, Organizational Slack Resources, and Managerial Perceptions on the Corporate Water Responsibility of Small- and Medium-Sized Corporations" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 7821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107821