Antecedents of Engagement within Online Sharing Economy Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

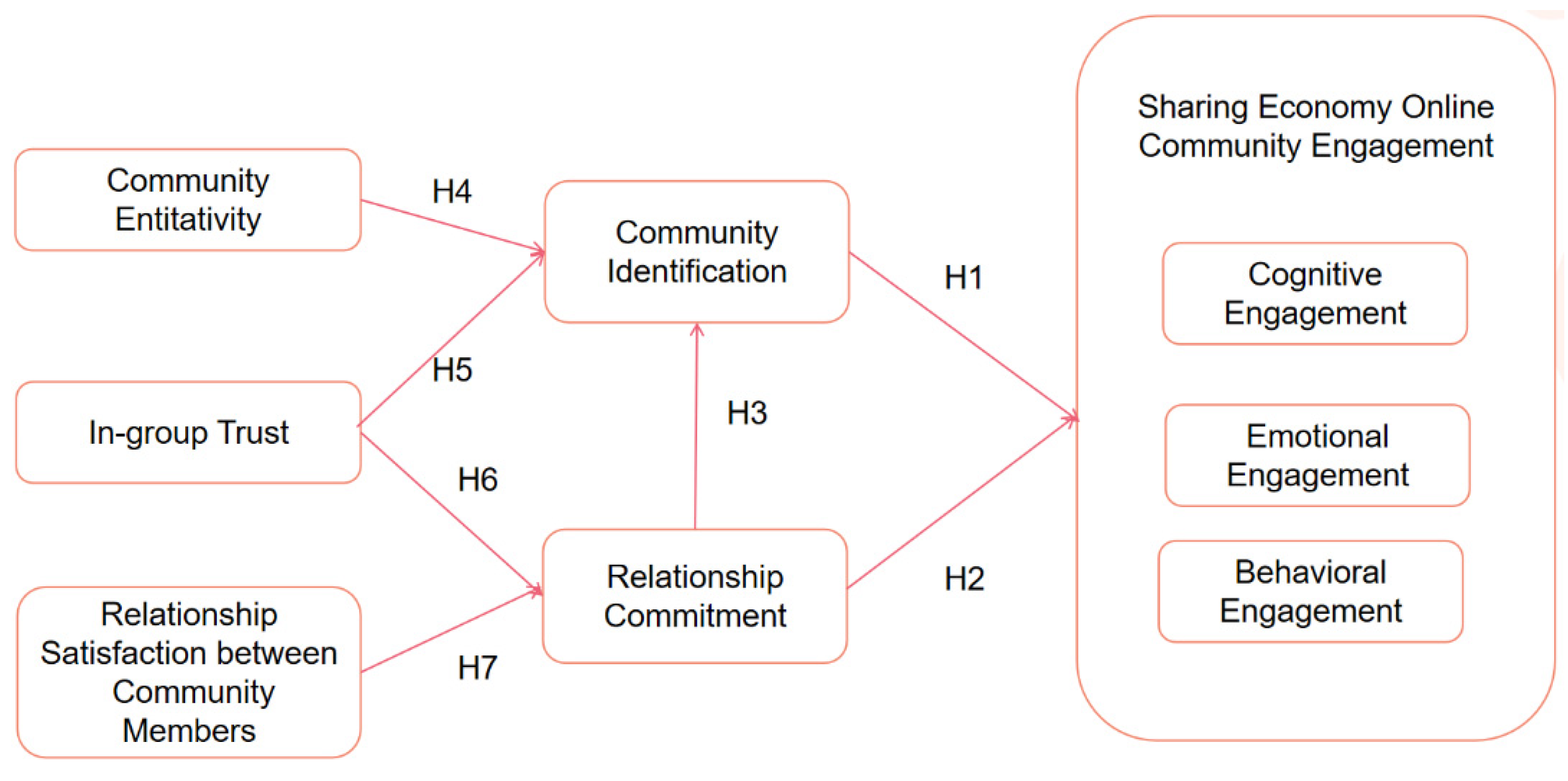

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. The Characteristics of Sharing Economy

2.2. Online Sharing Economy Community Engagement

2.3. Online Community Identification and Online Sharing Economy Community Engagement

2.4. Online Relationship Commitment and Online Sharing Economy Community Engagement

2.5. Online Community Identification and Online Relationship Commitment

2.6. Community Entitativity, In-Group Trust, and Online Community Identification

2.7. In-Group Trust, Relationship Satisfaction, and Relationship Commitment

2.8. Research Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Measures

4. Results

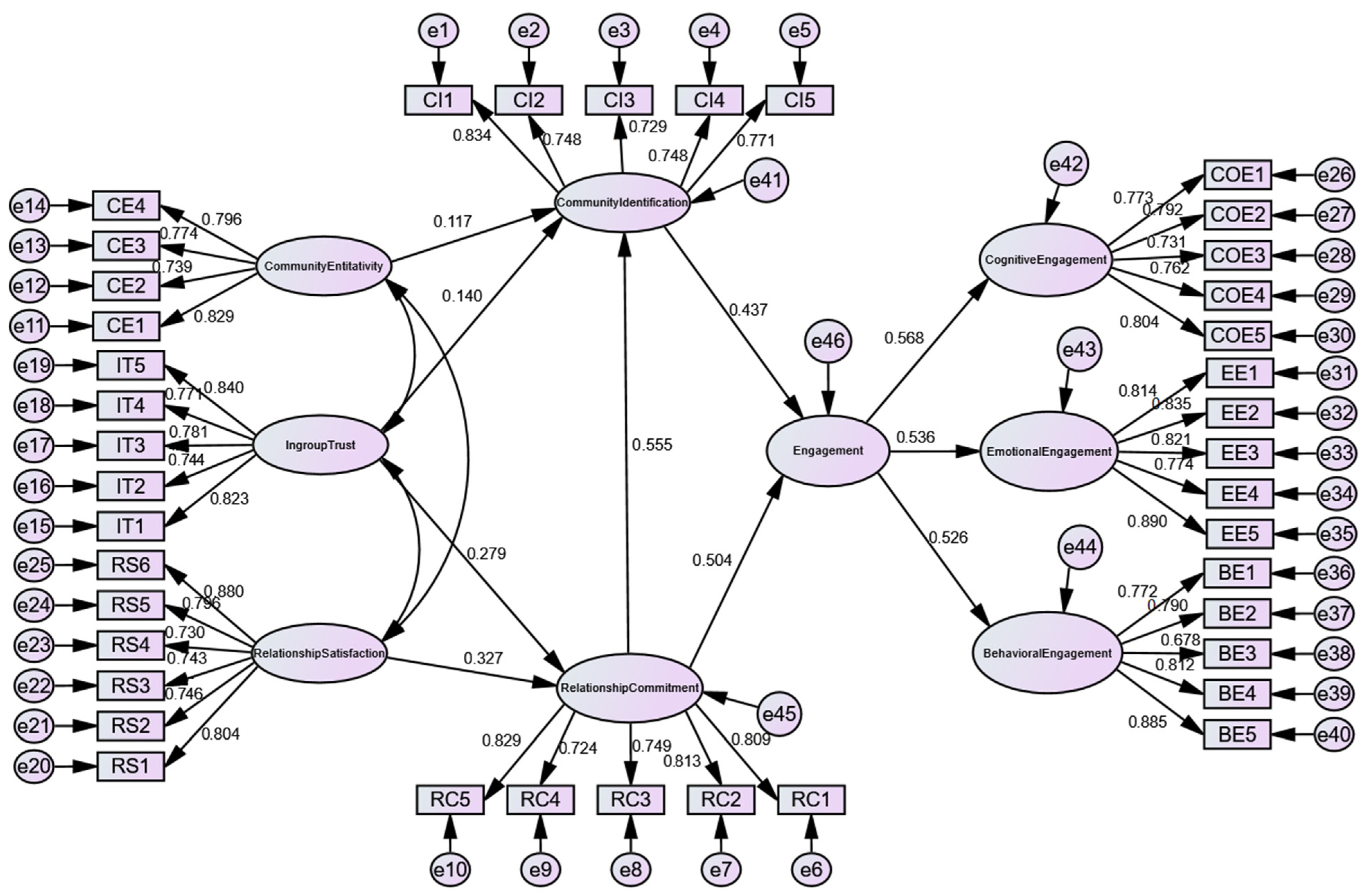

4.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions

5.1. Key Findings and Research Contribution

5.2. Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, M. Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartol, K.M.; Srivastava, A. Encouraging knowledge sharing: The role of organizational reward systems. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2002, 9, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, B.; Hofmann, E.; Kirchler, E. Do we need rules for “hat’s mine is yours”? Governance in collaborative consumption communities. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2756–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W. The Sharing Economy Model is Driving the Development of Green Economy 共享经济模式助力绿色经济发展; Accounting of Township Enterprises in China 中国乡镇企业会计: Beijing, China, 2017; pp. 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Schor, J.B.; Fitzmaurice, C.J. Collaborating and connecting: The emergence of the sharing economy. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Consumption; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 410–425. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, V. Why engagement? A second person take on social cognition. In Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rishika, R.; Kumar, A.; Janakiraman, R.; Bezawada, R. The effect of customers’ social media participation on customer visit frequency and profitability: An empirical investigation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, P.; Tsai, H.-T. Reciprocity norms and information-sharing behavior in online consumption communities: An empirical investigation of antecedents and moderators. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raïes, K.; Mühlbacher, H.; Gavard-Perret, M.-L. Consumption community commitment: Newbies’ and longstanding members’ brand engagement and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2634–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer Brand Engagement in Social Media: Conceptualization, Scale Development and Validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R.M.; Hanna, B.A.; Su, S.; Wei, J. Collective Identity, Collective Trust, and Social Capital: Linking Group Identification and Group Cooperation, 1st ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Smith, S.D. Engagement: An important bridging concept for the emerging SD logic lexicon. In Proceedings of the 2011 Naples Forum On Service, Naples, Italy, 14–17 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codagnone, C.; Martens, B. Scoping the Sharing Economy: Origins, Definitions, Impact and Regulatory Issues; JRC Working Papers on Digital Economy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kathan, W.; Matzler, K.; Veider, V. The sharing economy: Your business model’s friend or foe? Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, R.; Kozinets, R.V. Lateral exchange markets: How social platforms operate in a networked economy. J. Mark. 2018, 82, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.-P.; Turban, E. Introduction to the special issue social commerce: A research framework for social commerce. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.-C.; Csorba, L.M.; Isac, F.-L.; Rusu, S. Managing Sustainable Sharing Economy Platforms: A Stimulus–Organism–Response Based Structural Equation Modelling on an Emerging Market. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Lahiri, A.; Dogan, O.B. A strategic framework for a profitable business model in the sharing economy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 69, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L. Performing the sharing economy. Geoforum 2015, 67, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böcker, L.; Meelen, T. Sharing for people, planet or profit? Analysing motivations for intended sharing economy participation. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 23, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. Factors of satisfaction and intention to use peer-to-peer accommodation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Kumar, V. Drivers of brand community engagement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 54, 101949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Baron, R.A. Virtual customer environments: Testing a model of voluntary participation in value co-creation activities. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2009, 26, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algesheimer, R.; Dholakia, U.M.; Herrmann, A. The social influence of brand community: Evidence from European car clubs. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Jun, M.; Kim, M. Impact of online community engagement on community loyalty and social well-being. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2019, 47, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A. Engagement in school and out-of-school contexts: A multidimensional view of engagement. Theory Pract. 2011, 50, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldus, B.J.; Voorhees, C.; Calantone, R. Online brand community engagement: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algharabat, R.S.; Rana, N.P. Social Commerce in Emerging Markets and its Impact on Online Community Engagement. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 23, 1499–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B. Customer engagement with tourism brands: Scale development and validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Choe, M.-J.; Zhang, J.; Noh, G.-Y. The role of wishful identification, emotional engagement, and parasocial relationships in repeated viewing of live-streaming games: A social cognitive theory perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.G.; de Fátima Salgueiro, M.; Mateus, I. Say yes to Facebook and get your customers involved! Relationships in a world of social networks. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, S.; Wallace, B.C.; Lyu, H.; Silva, P.C.M.J. Modelling context with user embeddings for sarcasm detection in social media. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.00976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, C.; Donalds, C.; Osei-Bryson, K.-M. Investigating critical success factors in online learning environments in higher education systems in the Caribbean. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2018, 24, 582–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiltz, S.R.; Wellman, B. Asynchronous learning networks as a virtual classroom. Commun. ACM 1997, 40, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D.; Hogg, M.A. Comments on the motivational status of self-esteem in social identity and intergroup discrimination. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 18, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R.; Blader, S.L. Identity and cooperative behavior in groups. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2001, 4, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E. Psychological Sense of Community Among Treatment Analogue Group Members1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 11, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, B.D.; Suter, T.A.; Brown, T.J. Social versus psychological brand community: The role of psychological sense of brand community. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Lee, H. Travelers’ social identification and membership behaviors in online travel community. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Kim, S.S.; Morris, J.G. The central role of engagement in online communities. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M. Antecedents and purchase consequences of customer participation in small group brand communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2006, 23, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K.; Varki, S.; Brodie, R. Measuring the quality of relationships in consumer services: An empirical study. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 169–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huo, B.; Flynn, B.B.; Yeung, J. The impact of power and relationship commitment on the integration between manufacturers and customers in a supply chain. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W.; Fornell, C.; Lehmann, D.R. Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, K.; Head, M. The impact of infusing social presence in the web interface: An investigation across product types. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2005, 10, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Agnew, C.R. Ease of retrieval effects on relationship commitment: The role of future plans. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 42, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.-H.; Chang, C.-M. The influence of trust and perceived playfulness on the relationship commitment of hospitality online social network-moderating effects of gender. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 924–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, M.; Schanz, H. The sharing economy: A comprehensive business model framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.W.; Yuen, A.H. Understanding online knowledge sharing: An interpersonal relationship perspective. Comput. Educ. 2011, 56, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epp, A.M.; Price, L.L. Family Identity: A Framework of Identity Interplay in Consumption Practices. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatih, S.; Masood, H.; Zelal, A.R. An Empirical Study on the Role of Interpersonal and Institutional Trust in Organizational Innovativeness. Int. Bus. Res. 2011, 4, 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Sleebos, E. Organizational identification versus organizational commitment: Self-definition, social exchange, and job attitudes. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2006, 27, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patalano, C. A Study of the Relationship between Generational Group Identification and Organizational Commitment: Generation X vs. Generation Y.; Nova Southeastern University: Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Morewedge, C.K.; Chandler, J.J.; Smith, R.; Schwarz, N.; Schooler, J. Lost in the crowd: Entitative group membership reduces mind attribution. Conscious. Cogn. 2013, 22, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lickel, B.; Miller, N.; Stenstrom, D.M.; Denson, T.F.; Schmader, T. Vicarious retribution: The role of collective blame in intergroup aggression. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castano, E.; Yzerbyt, V.; Paladino, M.-P.; Sacchi, S. I belong, therefore, I exist: Ingroup identification, ingroup entitativity, and ingroup bias. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer-Rodgers, J.; Williams, M.J.; Hamilton, D.L.; Peng, K.; Wang, L. Culture and group perception: Dispositional and stereotypic inferences about novel and national groups. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogg, M.A.; Sherman, D.K.; Dierselhuis, J.; Maitner, A.T.; Moffitt, G. Uncertainty, entitativity, and group identification. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.H.; Kim, Y.M.; Lee, C.W.; Shim, G.Y.; Park, M.S.; Jung, H.S. Consumer adoption of virtual stores in Korea: Focusing on the role of trust and playfulness. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 652–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R.M. Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1999, 50, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. In whom we trust: Group membership as an affective context for trust development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Dhillon, G.S. Interpreting dimensions of consumer trust in e-commerce. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2003, 4, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.-C.; Csorba, L.M.; Isac, F.-L.; Rusu, S. Building Trust toward Sharing Economy Platforms beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic. Electronics 2022, 11, 2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, J.K.; Ferrin, D.L.; Rao, H.R. A Trust-Based Consumer Decision-Making Model in Electronic Commerce: The Role of Trust, Perceived Risk, and Their Antecedents. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 44, 544–564. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty, S.; Whitten, D.; Green, K. Understanding service quality and relationship quality in IS outsourcing: Client orientation & promotion, project management effectiveness, and the task-technology-structure fit. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2008, 48, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kale, P.; Singh, H.; Perlmutter, H. Learning and protection of proprietary assets in strategic alliances: Building relational capital. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C. Understanding the Effect of Customer Relationship Management Efforts on Customer Retention and Customer Share Development. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, K. Trust and TAM in Online Shopping: An Integrated Model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, X.B.; Agnew, C.R. Being Committed: Affective, Cognitive, and Conative Components of Relationship Commitment. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 1190–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmore, R.D.; Deaux, K.; McLaughlin-Volpe, T. An organizing framework for collective identity: Articulation and significance of multidimensionality. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 80–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.C.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. A Critical Review of Construct Indicators and Measurement Model Misspecification in Marketing and Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Obst, P. Community connections: Psychological Sense of Community and Identification in Geographical and Relational Settings. Ph.D. Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Liu, C.-C.; Lee, Y.-D. Effect of Commitment and Trust towards Micro-blogs on Consumer Behavioral Intention: A Relationship Marketing Perspective. Int. J. Electron. Bus. Manag. 2010, 8, 292–303. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, A.L.; Caudill, L.E.; Walker, L.S. Developing an entitativity measure and distinguishing it from antecedents and outcomes within online and face-to-face groups. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2020, 23, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Y. The role of mutual trust in building members’ loyalty to a C2C platform provider. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2009, 14, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røysamb, E.; Vittersø, J.; Tambs, K. The relationship satisfaction scale-psychometric properties. Nor. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverin, A.; Liljander, V. Does relationship marketing improve customer relationship satisfaction and loyalty? Int. J. Bank Mark. 2006, 24, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefansson, K.K.; Gestsdottir, S.; Geldhof, G.J.; Skulason, S.; Lerner, R.M. A bifactor model of school engagement: Assessing general and specific aspects of behavioral, emotional and cognitive engagement among adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2016, 40, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Shao, X.; Geng, Y.; Qu, R.; Niu, G.; Wang, Y. Development of the social media engagement scale for adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Lee, M. Building engagement in online brand communities: The effects of socially beneficial initiatives on collective social capital. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F.A. Social Identity Theory and Organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Harper, F.M.; Drenner, S.; Terveen, L.; Kraut, R.E. Building Member Attachment in Online Communities: Applying Theories of Group Identity and Interpersonal Bonds. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 841–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berscheid, E. Interpersonal relationships. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1994, 45, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 251 | 58.1 |

| Female | 181 | 41.9 | |

| Age | Under the age of 20 | 26 | 6.0 |

| 21–30 | 152 | 35.2 | |

| 31–40 | 109 | 25.2 | |

| 41–50 | 129 | 29.2 | |

| Over 50 | 19 | 4.4 | |

| Income | Under CNY 3000 | 96 | 22.2 |

| CNY 3000–7000 | 147 | 34.0 | |

| CNY 7000–10,000 | 126 | 29.2 | |

| Over CNY 10,000 | 63 | 14.6 | |

| Total Response | 432 | 100 | |

| Constructs | Number | Sources | Measurement Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community Identification | Five items | Obst (2004); Ray, Kim, and Morris (2014) [43,77] | I think the members of the online sharing economic community are one. |

| I think I am very similar to other members of the online sharing economy community. | |||

| I have a strong sense of belonging to the online sharing economy community. | |||

| I have a lot in common with members of the online sharing economy community. | |||

| I am no different from members of the online sharing economic community. | |||

| Relationship Commitment | Five items | Hsu, Liu, and Lee (2010); Ma and Yuen (2011) [52,78] | I am committed to maintaining relations with other members. |

| I hope the relationship with other members will last for a long time. | |||

| I would be sad if the relationship with other members ends in the near future. | |||

| I hope that the relationships with the other members will continue. | |||

| I hope to build good relations with the other members. | |||

| Community Entitativity | Four items | Hogg, Sherman, Dierselhuis, Maitner, and Moffitt, (2007); Blanchard (2020) [61,79] | My online sharing economy community is a unit. |

| All members of the online sharing economic community are in a group. | |||

| For members, joining an online sharing economic community is equivalent to joining a community. | |||

| For its members, the online sharing economy community is a group. | |||

| In-group Trust | Five items | Chen, Zhang, and Xu (2009); Semerciöz, Hassan, and Aldemr (2011); Dabija, Csorba, Isac, and Rusu (2022) [54,68,80] | I believe the members of the online sharing economy community. |

| I believe that other members of the online sharing economy community are trustworthy. | |||

| I think the members of the online sharing economy community are honest. | |||

| Members of the online sharing economy community perceive high credibility. | |||

| Even if not monitored, I would trust other members of the online sharing economy community. | |||

| Relationship Satisfaction | Six items | Semerciöz, Hassan, and Aldemr (2011); Røysamb, Vittersø and Tambs, (2014) [81,82] | I have a very good relationship with the members of the online sharing economy community. |

| I am very happy with the members and relationships of the online sharing economy community. | |||

| I am serious about my relationship with members of the online sharing economy community. | |||

| I want to communicate regularly with members of the online sharing economy community. | |||

| I feel very happy with my relationship with the members of the online sharing economy community. | |||

| I have many problems with the membership of the online sharing economy community. | |||

| Cognitive Engagement | Five items | Hollebeek, Glynn, and Brodie (2014); Stefansson, Gestsdottir, Geldhof, Skulason, and Lerner (2016) [10,83] | While engagement in the online sharing economy community, you will get more attention and evaluation than usual. |

| In the process of engagement in the online sharing economy community, I got a lot of attention and evaluation about me, and I found it very meaningful. | |||

| With the support and encouragement of others, there is a greater desire to join the online sharing economy community. | |||

| The more you use the sharing economy, the more you understand what an online sharing economy community is. | |||

| I often talk to people about what my gains have been from using the online sharing economy community. | |||

| Emotional Engagement | Five items | Han, Jun, and Kim (2019); Ni, Shao, Geng, Qu, Niu, and Wang (2020) [27,84] | It is very convenient to engage in the online sharing economy community. |

| It is comfortable to engage in the online sharing economy community. | |||

| It is happy to engage in the online sharing economy community. | |||

| I think the online sharing economy community is interesting. | |||

| I am excited by engagement in the online sharing economy community. | |||

| Behavioral Engagement | Five items | Baldus, Voorhees, and Calantone (2014); Wong and Lee (2022) [29,85] | I engagement in the online sharing economy community. |

| I am familiar with the use of online sharing economy communities. | |||

| I will actively choose to engage in online sharing economy communities. | |||

| I recommend online sharing economy communities to others. | |||

| I consider online sharing economy communities to be positive. |

| Rotated Component Matrix | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | α | ||

| Relationship Satisfaction | RS6 | 0.835 | −0.003 | 0.194 | 0.127 | 0.030 | 0.113 | 0.116 | 0.131 | 0.904 |

| RS5 | 0.783 | −0.010 | 0.164 | 0.148 | 0.100 | 0.080 | 0.127 | 0.074 | ||

| RS1 | 0.763 | 0.019 | 0.183 | 0.097 | 0.063 | 0.197 | 0.140 | 0.106 | ||

| RS4 | 0.753 | −0.013 | 0.147 | 0.076 | 0.080 | 0.125 | 0.110 | 0.023 | ||

| RS2 | 0.746 | −0.037 | 0.157 | 0.127 | 0.043 | 0.117 | 0.100 | 0.095 | ||

| RS3 | 0.728 | −0.048 | 0.185 | 0.156 | 0.105 | 0.103 | 0.119 | 0.057 | ||

| Emotional Engagement | EE5 | −0.042 | 0.865 | 0.118 | 0.037 | 0.092 | 0.148 | 0.124 | 0.081 | 0.915 |

| EE1 | −0.022 | 0.838 | 0.118 | 0.078 | 0.046 | 0.063 | 0.112 | 0.104 | ||

| EE3 | 0.060 | 0.829 | 0.085 | 0.101 | 0.168 | 0.118 | 0.087 | 0.022 | ||

| EE2 | −0.030 | 0.826 | 0.046 | 0.044 | 0.147 | 0.119 | 0.135 | 0.131 | ||

| EE4 | −0.066 | 0.766 | 0.094 | 0.076 | 0.071 | 0.227 | 0.133 | 0.079 | ||

| In-group Trust | IT1 | 0.169 | 0.082 | 0.834 | 0.024 | 0.075 | 0.127 | 0.092 | 0.011 | 0.894 |

| IT5 | 0.209 | 0.089 | 0.807 | 0.091 | 0.044 | 0.138 | 0.116 | 0.105 | ||

| IT3 | 0.241 | 0.099 | 0.770 | −0.030 | 0.027 | 0.068 | 0.099 | 0.127 | ||

| IT4 | 0.186 | 0.034 | 0.758 | 0.083 | 0.070 | 0.138 | 0.143 | 0.121 | ||

| IT2 | 0.186 | 0.173 | 0.751 | −0.010 | 0.057 | 0.105 | 0.085 | 0.071 | ||

| Behavioral Engagement | BE5 | 0.140 | 0.095 | 0.045 | 0.853 | 0.087 | 0.056 | 0.137 | 0.134 | 0.890 |

| BE4 | 0.116 | −0.025 | 0.052 | 0.826 | 0.037 | 0.169 | 0.108 | 0.156 | ||

| BE1 | 0.145 | 0.187 | 0.096 | 0.783 | 0.098 | 0.006 | 0.081 | 0.094 | ||

| BE2 | 0.146 | 0.045 | 0.002 | 0.766 | 0.117 | 0.117 | 0.167 | 0.166 | ||

| BE3 | 0.140 | 0.047 | −0.041 | 0.704 | 0.079 | 0.250 | 0.071 | 0.077 | ||

| Cognitive Engagement | COE5 | 0.082 | 0.041 | 0.084 | 0.098 | 0.810 | 0.087 | 0.128 | 0.129 | 0.881 |

| COE3 | 0.151 | 0.032 | 0.045 | 0.048 | 0.770 | 0.139 | 0.095 | 0.104 | ||

| COE2 | 0.144 | 0.162 | −0.001 | 0.120 | 0.768 | 0.096 | 0.142 | 0.133 | ||

| COE1 | 0.004 | 0.152 | 0.087 | 0.062 | 0.765 | 0.115 | 0.062 | 0.231 | ||

| COE4 | 0.004 | 0.150 | 0.053 | 0.080 | 0.760 | 0.121 | 0.121 | 0.179 | ||

| Relationship Commitment | RC5 | 0.130 | 0.187 | 0.176 | 0.135 | 0.112 | 0.754 | 0.233 | 0.007 | 0.889 |

| RC2 | 0.169 | 0.187 | 0.151 | 0.107 | 0.178 | 0.744 | 0.180 | 0.110 | ||

| RC1 | 0.185 | 0.184 | 0.138 | 0.089 | 0.229 | 0.736 | 0.189 | −0.005 | ||

| RC4 | 0.113 | 0.101 | 0.092 | 0.211 | 0.095 | 0.720 | 0.207 | 0.011 | ||

| RC3 | 0.230 | 0.144 | 0.128 | 0.123 | 0.072 | 0.702 | 0.230 | 0.070 | ||

| Community Identification | CI5 | 0.159 | 0.133 | 0.123 | 0.167 | 0.109 | 0.145 | 0.754 | 0.031 | 0.878 |

| CI1 | 0.197 | 0.127 | 0.180 | 0.177 | 0.110 | 0.217 | 0.744 | 0.057 | ||

| CI3 | 0.140 | 0.130 | 0.011 | 0.104 | 0.193 | 0.176 | 0.742 | 0.022 | ||

| CI4 | 0.161 | 0.132 | 0.126 | 0.113 | 0.079 | 0.170 | 0.736 | 0.097 | ||

| CI2 | 0.078 | 0.130 | 0.157 | 0.054 | 0.116 | 0.260 | 0.725 | 0.068 | ||

| Community Entitativity | CE4 | 0.084 | 0.027 | 0.043 | 0.137 | 0.233 | 0.028 | 0.078 | 0.812 | 0.865 |

| CE3 | 0.085 | 0.147 | 0.093 | 0.135 | 0.151 | 0.008 | 0.037 | 0.798 | ||

| CE1 | 0.145 | 0.097 | 0.181 | 0.168 | 0.161 | 0.119 | 0.032 | 0.787 | ||

| CE2 | 0.131 | 0.148 | 0.111 | 0.178 | 0.238 | 0.004 | 0.092 | 0.716 | ||

| Eigenvalue | 11.682 | 3.935 | 3.168 | 2.702 | 2.298 | 1.594 | 1.508 | 1.305 | ||

| Variance Explained | 29.204 | 9.838 | 7.92 | 6.754 | 5.746 | 3.986 | 3.771 | 3.263 | ||

| Variance Cumulative | 29.204 | 39.043 | 46.963 | 53.717 | 59.463 | 63.449 | 67.22 | 70.483 | ||

| KMO and Bartlett’s Test | 0.918 | |||||||||

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 11,080.371 | ||||||||

| Df | 780 | |||||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Identification | 0.768 | |||||||

| Relationship Commitment | 0.645 | 0.786 | ||||||

| Relationship Commitment | 0.298 | 0.279 | 0.785 | |||||

| In-group Trust | 0.420 | 0.446 | 0.337 | 0.793 | ||||

| Relationship Satisfaction | 0.453 | 0.462 | 0.346 | 0.523 | 0.784 | |||

| Cognitive Engagement | 0.413 | 0.436 | 0.524 | 0.243 | 0.273 | 0.773 | ||

| Emotional Engagement | 0.394 | 0.445 | 0.304 | 0.286 | 0.064 | 0.342 | 0.828 | |

| Behavioral Engagement | 0.420 | 0.408 | 0.438 | 0.203 | 0.394 | 0.312 | 0.230 | 0.790 |

| H | Path | Estimate * | S.E. | C.R. | p | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Community Identification →Engagement | 0.437 | 0.042 | 4.913 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | Relationship Commitment →Engagement | 0.504 | 0.049 | 5.505 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | Relationship Commitment → Community Identification | 0.555 | 0.064 | 9.924 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4 | Community Entitativity → Community Identification | 0.117 | 0.058 | 2.449 | 0.014 | Supported |

| H5 | In-group Trust → Community Identification | 0.140 | 0.057 | 2.650 | 0.008 | Supported |

| H6 | In-group Trust → Relationship Commitment | 0.279 | 0.056 | 4.773 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H7 | Relationship Satisfaction → Relationship Commitment | 0.327 | 0.055 | 5.539 | 0.000 | Supported |

| χ2 = 1404.131 (df = 727, p = 0.000), GFI = 0.863, AGFI = 0.846, RFI = 0.869, IFI = 0.937, TLI = 0.932, CFI = 0.937, RMSEA = 0.046, SRMR = 0.0740 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, Y.; Bae, B.-R. Antecedents of Engagement within Online Sharing Economy Communities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8322. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108322

Cai Y, Bae B-R. Antecedents of Engagement within Online Sharing Economy Communities. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):8322. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108322

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Yunwei, and Byung-Ryul Bae. 2023. "Antecedents of Engagement within Online Sharing Economy Communities" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 8322. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108322

APA StyleCai, Y., & Bae, B.-R. (2023). Antecedents of Engagement within Online Sharing Economy Communities. Sustainability, 15(10), 8322. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108322