Pandemic Dining Dilemmas: Exploring the Determinants of Korean Consumer Dining-Out Behavior during COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Dining-Out Intention and Behavior

2.2. Risk Information-Seeking Behavior and Dining-Out Behavior

2.3. Pandemic Fear and Dining-Out Behavior

3. Methodology

3.1. Construct Measures

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

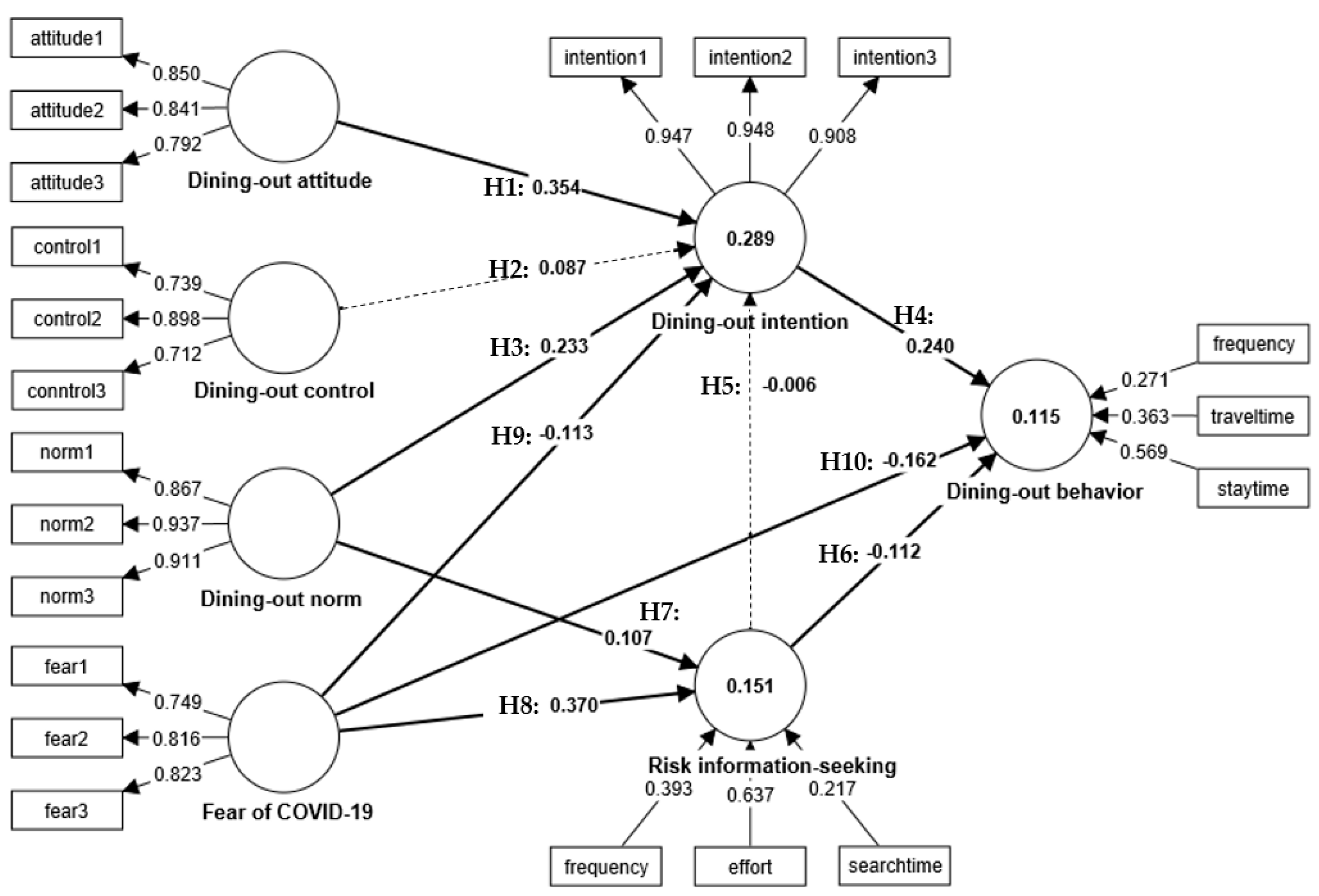

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Are, E.B.; Song, Y.; Stockdale, J.E.; Tupper, P.; Colijn, C. COVID-19 endgame: From pandemic to endemic? Vaccination, reopening and evolution in low-and high-vaccinated populations. J. Theor. Biol. 2023, 559, 111368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancolella, M.; Colona, V.L.; Mehrian-Shai, R.; Watt, J.L.; Luzzatto, L.; Novelli, G.; Reichardt, J.K. COVID-19 2022 update: Transition of the pandemic to the endemic phase. Hum. Genom. 2022, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parady, G.; Taniguchi, A.; Takami, K. Travel behavior changes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: Analyzing the effects of risk perception and social influence on going-out self-restriction. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 7, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Lian, X.; Su, X.; Wu, W.; Marraro, G.A.; Zeng, Y. From SARS and MERS to COVID-19: A brief summary and comparison of severe acute respiratory infections caused by three highly pathogenic human coronaviruses. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.H.; Son, J.H.; Kim, G.J. An exploratory study of changes in consumer dining out behavior before and during COVID-19. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizek, M.G.; Frash, R.E.; McLeod, B.M.; Patience, M.O. Independent restaurant operator perspectives in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality industry: Review of the current situations and a research agenda. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Yoon, H.H.; Song, M.K. A study on dining-out trends using big data: Focusing on changes since COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, N. The tourism–leisure behavioural continuum. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 972–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Lee, J.S.; Mohamed, M.A.; Ng, B.F. Infection risk of SARS-CoV-2 in a dining setting: Deposited droplets and aerosols. Build. Environ. 2022, 213, 108888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Kim, K.; Ma, F.; DiPietro, R. Key factors driving customers’ restaurant dining behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 836–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persing, A.J.; Roberts, B.; Lotter, J.T.; Russman, E.; Pierce, J. Evaluation of ventilation, indoor air quality, and probability of viral infection in an outdoor dining enclosure. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2022, 19, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Chen, H.; Lee, Y.M. COVID-19 preventive measures and restaurant customers’ intention to dine out: The role of brand trust and perceived risk. Serv. Bus. 2021, 16, 581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, C.L.; Taylor, S., Jr.; Taylor, D.C. Pivot! How the restaurant industry adapted during COVID-19 restrictions. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2021, 35, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenhaute, H.; Gellynck, X.; De Steur, H. COVID-19 safety measures in the food service sector: Consumers’ attitudes and transparency perceptions at three different stages of the Pandemic. Foods 2022, 11, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Liu-Lastres, B. Consumer′ dining behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: An Application of the Protection Motivation Theory and the Safety Signal Framework. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, E.; Cheng, Y. Customers’ risk perception and dine-out motivation during a pandemic: Insight for the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 6, 244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, D.E.; Kasprzyk, D. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. Health Behav. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 70, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Im, J.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. The theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model approach to consumer behavior regarding organic menus. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.L.; Fang, C.Y. Applying an extended theory of planned behavior for sustaining a landscape restaurant. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.J. Investigating beliefs, attitudes, and intentions regarding green restaurant patronage: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior with moderating effects of gender and age. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amin, M.; Arefin, M.S.; Alam, M.R.; Ahammad, T.; Hoque, M.R. Using mobile food delivery applications during COVID-19 pandemic: An extended model of planned behavior. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2021, 27, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.P.; Magnan, R.E.; Kramer, E.B.; Bryan, A.D. Theory of planned behavior analysis of social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Focusing on the intention–behavior gap. Ann. Behav. Med. 2021, 55, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Harris, P.R.; Epton, T. Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 511–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Webb, T.L. The intention–behavior gap. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2016, 10, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, K.A.; Trafimow, D.; Moroi, E. The importance of subjective norms on intentions to perform health behaviors. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2381–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Ju, I.; Ohs, J.E.; Hinsley, A.; Muzumdar, J. Information seeking during the COVID-19 pandemic: Application of the risk information seeking and processing model. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerbner, G.; Gross, L. Living with television: The violence profile. J. Commun. 1976, 26, 172–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbner, G.; Gross, L.; Morgan, M.; Signorielli, N. Living with television: The dynamics of the cultivation process. Perspect. Media Eff. 1986, 1986, 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kasperson, R.E.; Renn, O.; Slovic, P.; Brown, H.S.; Emel, J.; Goble, R.; Kasperson, J.X.; Ratick, S. The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Anal. 1988, 8, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyanto, I.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Thapa, B.; Srinivasan, S.; Villegas, J.; Matyas, C.; Kiousis, S. Predicting information seeking regarding hurricane evacuation in the destination. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.J.; Dunwoody, S.; Neuwirth, K. Proposed model of the relationship of risk information seeking and processing to the development of preventive behaviors. Environ. Res. 1999, 80, S230–S245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlor, L.; Dunwoody, S.; Griffin, R.J.; Neuwirth, K.; Giese, J. Studying heuristic-systematic processing of risk communication. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2003, 23, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, R. (Ed.) Public Health Communication: Evidence for Behavior Change; Routledge: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, A.; Özbük, R.M.Y. What influences consumer food waste behavior in restaurants? An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Waste Manag. 2020, 117, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.; Arendt, S.W. Understanding healthy eating behaviors at casual dining restaurants using the extended theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 53, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasetti, A.; Singer, P.; Troisi, O.; Maione, G. Extended theory of planned behavior (ETPB): Investigating customers’ perception of restaurants’ sustainability by testing a structural equation model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, L. The methodology of risk perception research. Qual. Quant. 2000, 34, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damasio, A. Descartes′ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P. Basic emotions. In Handbook of Cognition and Emotion; Dalgleish, T., Power, T., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ortony, A.; Turner, T.J. What′s basic about basic emotions? Psychol. Rev. 1990, 97, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restrepo-Castro, J.C.; Labrador, F.J.; Gantiva, C.; Camacho, K.; Castro-Camacho, L. The effect of information seeking behaviors in fear control. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2023, 78, 101797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.O.; Andrews, J.E.; Johnson, J.D.; Allard, S.L. Avoiding versus seeking: The relationship of information seeking to avoidance, blunting, coping, dissonance, and related concepts. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2005, 93, 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio, A.; Carvalho, G.B. The nature of feelings: Evolutionary and neurobiological origins. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.H.; Joseph, J.G. AIDS and behavioral change to reduce risk: A review. Am. J. Public Health 1988, 78, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, D.L.; Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W. A meta-analysis of research on protection motivation theory. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwin, M.O.; Stanaland, A.J.; Chan, D. Using protection motivation theory to predict condom usage and assess HIV health communication efficacy in Singapore. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lorca, M.; Martínez-Lorca, A.; Criado-Álvarez, J.J.; Armesilla, M.D.C.; Latorre, J.M. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Validation in spanish university students. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, K.; Lennox, R. Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural equation perspective. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Winklhofer, H.M. Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a TPB Questionnaire: Conceptual and Methodological Considerations. 2002. Available online: https://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Gleicher, F.; Petty, R.E. Expectations of reassurance influence the nature of fear-stimulated attitude change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 28, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.E.; Chambless, D.L.; Ahrens, A. Are emotions frightening? An extension of the fear of fear construct. Behav. Res. Ther. 1997, 35, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Luo, Q.; Ritchie, B.W. Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Ranjan, P.; Vikram, N.K.; Kaur, D.; Sahu, A.; Dwivedi, S.N.; Baitha, U.; Goel, A. A short questionnaire to assess changes in lifestyle-related behaviour during COVID 19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 1697–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, P.B.; Gaskin, J. Partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) for building and testing behavioral causal theory: When to choose it and how to use it. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2014, 57, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Riefler, P.; Roth, K.P. Advancing formative measurement models. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 1203–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Klein, K.; Wetzels, M. Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T.J. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulker-Demirel, E.; Ciftci, G. A systematic literature review of the theory of planned behavior in tourism, leisure and hospitality management research. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladeira, W.J.; Santini, F.D.O.; Araujo, C.F.; Sampaio, C.H. A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction in tourism and hospitality. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 975–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.K. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32. Available online: https://marketing-bulletin.massey.ac.nz/index.php/mb/article/view/53/45 (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Shahbaz, M.; Bilal, M.; Akhlaq, M.; Moiz, A.; Zubair, S.; Iqbal, H.M. Strategic measures for food processing and manufacturing facilities to combat coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 14, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messabia, N.; Fomi, P.R.; Kooli, C. Managing restaurants during the COVID-19 crisis: Innovating to survive and prosper. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Characteristics | Frequency (%) | Variable | Characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female Male | 268 (50%) 268 (50%) | Marital status | Unmarried Married Others | 227 (42.4%) 301 (56.2%) 8 (1.5%) |

| Age | 20 s 30 s 40 s 50 s or above | 135 (25.2%) 133 (24.8%) 134 (25.0%) 134 (25.0%) | Education | High school College/University Graduate school | 131 (24.4%) 358 (66.8%) 47(8.8%) |

| Variable | Items | Mean (SD) | Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR (rho_a) | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | I find dining-out to be a favorable experience. | 3.11 (0.757) | 0.850 | 0.772 | 0.774 | 0.686 |

| I find dining-out to be a pleasurable experience. | 3.18 (0.835) | 0.841 | ||||

| I find dining-out to be an enjoyable experience. | 3.90 (0.689) | 0.792 | ||||

| Control | I believe I have control over my decision to dine out in the future. | 3.45 (0.924) | 0.867 | 0.688 | 0.726 | 0.620 |

| I feel that I can dine out whenever I want. | 3.59 (0.909) | 0.937 | ||||

| I have the necessary resources (time, money) and ability to dine out. | 3.68 (0.808) | 0.911 | ||||

| Norm | People who are important to me would want me to dine out. | 2.86 (0.838) | 0.712 | 0.891 | 0.909 | 0.820 |

| People who are important to me would think I should dine out. | 2.77 (0.873) | 0.739 | ||||

| People who are important to me would consider dining out to be necessary. | 2.79 (0.903) | 0.898 | ||||

| Intention | I intend to dine out in the future. | 3.18 (1.056) | 0.947 | 0.927 | 0.927 | 0.873 |

| I plan to dine out in the future. | 3.05 (1.080) | 0.948 | ||||

| I intend to continue dining out regularly. | 3.22 (1.041) | 0.908 | ||||

| Fear | I feel anxious about the COVID-19 pandemic. | 4.25 (0.706) | 0.749 | 0.713 | 0.721 | 0.634 |

| The COVID-19 pandemic makes me feel nervous. | 4.32 (0.810) | 0.816 | ||||

| The COVID-19 pandemic frightens me. | 3.72 (0.904) | 0.823 |

| Attitude | Control | Norm | Intention | Fear | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | |||||

| Control | 0.510 | ||||

| Norm | 0.457 | 0.432 | |||

| Intention | 0.544 | 0.355 | 0.426 | ||

| Fear | 0.136 | 0.159 | 0.075 | 0.09 |

| Attitude | Control | Norm | Intention | Seeking | Fear | Dine-Out | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| attitude1 | 0.850 | 0.287 | 0.333 | 0.380 | −0.031 | 0.024 | 0.122 |

| attitude2 | 0.841 | 0.277 | 0.339 | 0.341 | 0.034 | 0.085 | 0.097 |

| attitude3 | 0.792 | 0.361 | 0.271 | 0.423 | 0.016 | 0.108 | 0.030 |

| control1 | 0.332 | 0.296 | 0.867 | 0.295 | 0.087 | 0.034 | 0.000 |

| control2 | 0.351 | 0.306 | 0.937 | 0.361 | 0.108 | 0.037 | 0.030 |

| control3 | 0.343 | 0.307 | 0.911 | 0.396 | 0.124 | 0.020 | 0.034 |

| norm1 | 0.254 | 0.712 | 0.265 | 0.202 | 0.122 | 0.040 | 0.029 |

| norm2 | 0.294 | 0.739 | 0.259 | 0.196 | 0.094 | 0.131 | 0.028 |

| norm3 | 0.339 | 0.898 | 0.272 | 0.270 | 0.037 | 0.083 | 0.039 |

| intention1 | 0.449 | 0.286 | 0.337 | 0.947 | −0.015 | −0.075 | 0.230 |

| intention2 | 0.412 | 0.278 | 0.360 | 0.948 | −0.001 | −0.075 | 0.260 |

| intention3 | 0.443 | 0.238 | 0.402 | 0.908 | −0.009 | −0.038 | 0.215 |

| fear1 | 0.034 | 0.098 | −0.023 | −0.060 | 0.259 | 0.749 | −0.158 |

| fear2 | 0.087 | 0.121 | 0.111 | −0.011 | 0.319 | 0.816 | −0.143 |

| fear3 | 0.086 | 0.041 | −0.011 | −0.086 | 0.311 | 0.823 | −0.218 |

| Construct | Item | Description | Mean (SD) | VIF | Outer Loading | Outer Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk information-seeking behavior | frequency | Search frequency | 4.00 (0.688) | 1.902 | 0.937 *** | 0.637 *** |

| effort | Search effort | 3.68 (0.844) | 1.862 | 0.838 *** | 0.393 ** | |

| time | Time spent on each search | 32.98 (41.69) | 1.029 | 0.341 *** | 0.217 * | |

| Dining-out behavior change | frequency | Dining-out frequency | 1.68 (0.975) | 1.387 | 0.696 *** | 0.271 * |

| traveltime | time taken to reach the dining place | 2.27 (0.956) | 1.520 | 0.789 *** | 0.363 * | |

| staytime | time spent at the dining place | 1.91 (0.923) | 1.848 | 0.923 *** | 0.569 *** |

| Variable | R2 | Adj. R2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dining-out intention | 0.289 | 0.282 | 0.273 |

| COVID19 infoseeking | 0.151 | 0.147 | 0.136 |

| Dining-out behavior | 0.115 | 0.110 | 0.049 |

| Path | Original | Sample Mean | StDev | t-Statistics | f2 | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | 0.354 | 0.353 | 0.047 | 7.516 *** | 0.137 | S |

| H2 | 0.087 | 0.092 | 0.051 | 1.702 * | 0.009 | S |

| H3 | 0.233 | 0.233 | 0.048 | 4.855 *** | 0.062 | S |

| H4 | 0.240 | 0.242 | 0.040 | 6.064 *** | 0.065 | S |

| H5 | −0.006 | −0.008 | 0.043 | 0.138 | 0.000 | NS |

| H6 | −0.112 | −0.115 | 0.052 | 2.13 * | 0.012 | S |

| H7 | 0.107 | 0.108 | 0.044 | 2.418 ** | 0.013 | S |

| H8 | 0.370 | 0.375 | 0.041 | 8.941 *** | 0.161 | S |

| H9 | −0.113 | −0.113 | 0.039 | 2.903 ** | 0.015 | S |

| H10 | −0.162 | −0.165 | 0.054 | 2.991 ** | 0.025 | S |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baek, U.; Lee, S.K. Pandemic Dining Dilemmas: Exploring the Determinants of Korean Consumer Dining-Out Behavior during COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8323. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108323

Baek U, Lee SK. Pandemic Dining Dilemmas: Exploring the Determinants of Korean Consumer Dining-Out Behavior during COVID-19. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):8323. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108323

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaek, Unji, and Seul Ki Lee. 2023. "Pandemic Dining Dilemmas: Exploring the Determinants of Korean Consumer Dining-Out Behavior during COVID-19" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 8323. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108323