Environmental Protection Provisions in International Investment Agreements: Global Trends and Chinese Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Environmental Protection Concerns in International Investment

2. Environmental Protection—Related Rules in IIA Texts and Arbitration Practices

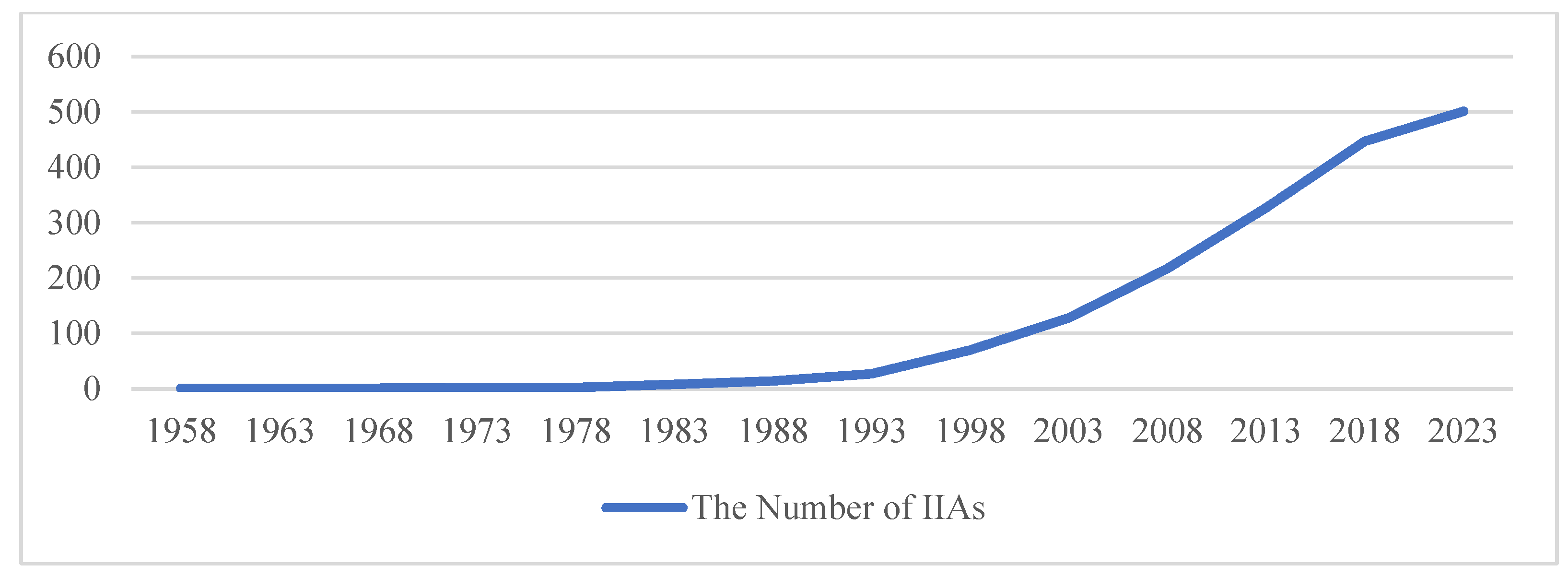

2.1. Environmental Clauses in IIAs: A Global Trend

- The provision preserving the host states’ regulatory power: The most common, and additionally the oldest, type of environmental protection-related clause is the preservation of the host state’s police power over relevant issues in foreign investments via exceptional clauses [8]. As an example, the US Model BIT (2012) includes a stand-alone provision on “Investment and Environment” demanding the contracting parties’ respect for and full implementation of the host state’s environmental policies and allowing an exception for the host state’s liability in taking environmental protection measures (Article 12). Even now, this remains the most common category. IIAs finalized in 2021 continued this trend towards providing room for host states to regulate FDI [10]. In contrast to an aspirational statement in the preamble, references to the environment in the main text of BITs or TIPs are often phrased as enforceable terms requiring investors to comply with environmental measures imposed by host states and, probably more importantly, not to challenge the validity or legality of such measures through the ISDS.

- The provision recognizing environmental protection as a treaty objective: Acknowledging environmental protection as one of the treaty objectives—commonly stipulated in the preambles of BITs or TIPs, as prescribed in Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties—is the second most common category. The forewords to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the Canada–EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement and the ECT contain allusions to the treaty purposes, including these references to the environment.

- The provision prescribing states’ continuing duty to impose environmental protection measures: The host state’s continuing commitment to implement environmental protection measures is the least common category, whereby the host state is obliged not to reduce environmental standards so as to avoid “a regulatory race to the bottom [8,21]”. This is the obligation incumbent on the host state to maintain a certain level of environmental standards and measures. By importing such relevant goals, BITs are able to cover environmental protection issues thoroughly.

- With a hybrid model comprising both an emphasis on environmental protection as parties’ mutual objective and a requirement for high-level environmental protection standards, The Netherlands Model BIT (2019) addresses environmental concerns systemically. First, its preamble states that the BIT’s policy objective may be fulfilled without compromising the host states’ police power by measures necessary for achieving the relevant targets, such as environmental protection. Second, in Article 6, Sustainable Development, the contracting parties guarantee that their investment regulatory institutions provide for and encourage a higher-level protection of the environment. In addition, the contracting parties ensure not to lower the degree of environmental protection prescribed by relevant domestic legislation, but reaffirm the host state’s treaty duties under the international agreements concerning environmental protection. Moreover, as a relatively rare fourth paradigm, Article 7, “Corporate Social Responsibility”, stipulates the obligations of investors and investments in the field of environmental protection. This CSR provision essentially alters the BIT paradigm by imposing obligations on investors. The Indian BIT also addresses the conduct of investors. Article 12 of the India Model BIT (2015) requires investors to comply with Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) principles and rules.

2.2. The Effect of International Environmental Instruments over FDI

2.3. Environmental Protection in Investment Arbitration

2.4. Applying Environment Rules in International Investment Arbitration

3. Environmental Protection in FDI Law in China

4. Environmental Protection Provisions in China’s IIAs: Status Quo and Challenges

- Treaty principles and objectives contained therein: Although the environmental protection content is not provided in detail, the China–Tanzania BIT (2013) includes the notion of CSR for the first time in the preamble and stipulates that both contracting parties are “(e)ncouraging investors to respect corporate social responsibilities”. The word “(e)ncouraging” may suggest a soft-law nature to this clause and that it imposes no legally binding obligation on the contracting parties. The China–Canada BIT (2012) emphasizes the party states’ right to regulate the FDI by providing in the preamble for the promotion of investment based on the principle of sustainable development. The China–Swiss FTA (2013) specifies in its preamble that the contracting parties acknowledge “the importance of good corporate governance and corporate social responsibility for sustainable development” and affirm “their aim to encourage enterprises to observe internationally recognized guidelines and principles in this respect”. However, these clauses are not well respected due to their lack of practicability [83]. As discussed above, the objective clause may turn out to be more decisive in investment arbitration, as the tribunal may rely on this clear statement to exempt the host state’s liability when it exercises its regulatory power.

- Clauses on environmental measures: Article 23 of the China–Japan–Korea Trilateral Investment Agreement (2012), which for the first time contains a specific “Environmental Measures” clause, requires that “(e)ach Contracting Party recognizes that it is inappropriate to encourage investment by investors of another Contracting Party by relaxing its environmental measures. To this effect each Contracting Party should not waive or otherwise derogate from such environmental measures as an encouragement for the establishment, acquisition or expansion of investments in its territory”. In contrast to this passive clause, under which the host state merely promises not to relax its environmental measures to attract foreign investment, the regulatory power over the environment can also be positively granted to the host state. For instance, some of China’s IIAs clearly permit the host state to adopt environmental measures. To illustrate, Article 8.9 in paragraph 3(d), “Performance Requirements”, in the China–Mauritius FTA (2019) states that commitments “shall not be construed to prevent a Party from adopting or maintaining measures, including environmental measures: (i) necessary to secure compliance with the laws and regulations that are not inconsistent with this Agreement; (ii) necessary to protect human, animal, or plant life or health; or (iii) related to the conservation of living and non-living exhaustible natural resources”. In addition to allowing the host state to implement environmental measures, three conditions are attached to the exercising of this regulatory power. The aim of these provisions is to avoid the regulatory “race to the bottom” by contracting states [8].

- Indirect expropriation clauses: The China–Uzbekistan BIT (2011) clearly expresses the desire to promote sustainable development in its preamble and specifies in Article 6.1 “Expropriations” that “(e)xcept in exceptional circumstances, such as the measures adopted severely surpassing the necessity of maintaining corresponding reasonable public welfare, non-discriminatory regulatory measures adopted by one Contracting Party for the purpose of legitimate public welfare, such as public health, safety and environment, do not constitute indirect expropriation”. This is an indirect expropriation clause, being a supplement to the conventional expropriation clause specifying four elements to justify a lawful expropriation. The China–Canada BIT (2012) includes a similar clause (Annex B.10. para 3). The effect of this indirect expropriation clause is to justify the host state’s health, safety, and environmental measures, which are non-discriminatory and serve legitimate public objectives. Applying such measures would not render the host state liable for expropriation.

- Exception clause: A typical exception clause is included in the BIT to allow the contracting party to adopt or maintain measures, including environmental strategies, as long as certain conditions are satisfied.Article 33 of the China–Canada BIT includes this exception clause as follows: “2. Provided that such measures are not applied in an arbitrary or unjustifiable manner, or do not constitute a disguised restriction on international trade or investment, nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to prevent a Contracting Party from adopting or maintaining measures, including environmental measures:

- (a)

- necessary to ensure compliance with laws and regulations that are not inconsistent with the provisions of this Agreement;

- (b)

- necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health; or

- (c)

- relating to the conservation of living or non-living exhaustible natural resources if such measures are made effective in conjunction with restrictions on domestic production or consumption”.

- 5.

- Non-jurisdiction clauses: According to Article 9.11B in Chapter 9 Investor-state Dispute Settlement of the ChAFTA (2015), measures taken by a party that are non-discriminatory and for legitimate public welfare—such as those relating to public health, safety, the environment, public morals, or public order—shall not be the subject of a claim. This clause functions as a waiver clause, exempting any liability of the host state arising out of environmental measures, as long as such measures are not discriminatory and are in the public’s interests. Although this non-jurisdiction clause acts like an exception clause, it can avoid a second guess by the tribunal when it comes to adjudicating a dispute and interpreting the exception clause. In this sense, this is a clause barring the investor from bringing a dispute surrounding the environmental protection measure to investment arbitration. As a result, it can save the host state and investors the potential costs of arbitration.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mabey, N.; McNally, R. Foreign Direct Investment and the Environment: From Pollution Havens to Sustainable Development; A WWF-UK Report; WWF-UK: Woking, UK, 1999; p. 3. Available online: http://assets.wwf.org.uk/downloads/fdi.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Marisi, F. Environmental Interests in Investment Arbitration: Challenges and Directions; Kluwer Law International BV: Zuid-Holland, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson, A.K. The Sociology of Ecologically Unequal Exchange, Foreign Investment Dependence and Environmental Load Displacement: Summary of the Literature and Implications for Sustainability. J. Political Ecol. 2016, 32, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garsous, G.; Koźluk, T. Foreign Direct Investment and the Pollution Haven Hypothesis: Evidence from Listed Firms; OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1379; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017; p. 7. Available online: https://one.oecd.org/document/ECO/WKP(2017)11/en/pdf (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Ren, S.; Yu, H.; Wu, H. How Does Green Investment Affect Environmental Pollution? Evidence from China. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2022, 81, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.A.; Elliott, R.J.R.; Zhang, J. Growth, Foreign Direct Investment, and the Environment: Evidence from Chinese Cities. J. Reg. Sci. 2011, 51, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Liu, Y.-M. Has the Development of FDI and Foreign Trade Contributed to China’s CO2 Emissions? An Empirical Study with Provincial Panel Data. Nat. Hazards 2015, 76, 1079–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beharry, C.L.; Kuritzky, M.E. Going Green: Managing the Environment through International Investment Arbitration. Am. Univ. Int. Law Rev. 2015, 30, 383–430. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2015: Reforming International Investment Governance. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2015_en.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2022: International Tax and Sustainable Investment. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2022_en.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- United Nations General Assembly. A/RES/60/1. 2005 World Summit Outcome. 24 October 2005. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_60_1.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Van den Berghe, A.; Tienhaara, K. Potential Solutions for Phase 3: Aligning the Objectives of UNCITRAL Working Group III with States. In International Obligations to Combat Climate Change; ClientEarth: London, UK; pp. 3–9. Available online: https://uncitral.un.org/sites/uncitral.un.org/files/media-documents/uncitral/en/wgiii_clientearth.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Energy Charter Secretariat. Decision of the Energy Charter Conference. 6 October 2019. Available online: https://www.energycharter.org/fileadmin/DocumentsMedia/CCDECS/2019/CCDEC201908.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Gazzini, T. Bilateral Investment Treaties and Sustainable Development. J. World Invest. Trade 2014, 15, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengoa, M.; Sanchez-Robles, B.; Shachmurove, Y. Do Trade and Investment Agreements Promote Foreign Direct Investment within Latin America? Evidence from a Structural Gravity Model. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alschner, W.; Tuerk, E. The Role of International Investment Agreements in Fostering Sustainable Development. In Investment Law within International Law: Integrationist Perspectives; Baetens, F., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gehring, M.; Tokas, M. Synergies and Approaches to Climate Change in International Investment Agreements: Comparative Analysis of Investment Liberalization and Investment Protection Provisions in European Union Agreements. J. World Invest. Trade 2022, 23, 778–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L. International investment agreements and climate change: The potential for investor-state conflicts and possible strategies for minimizing it. Environ. Law Rep. News Anal. 2009, 39, 11153. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2012: Towards a New Generation of Investment Policies. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2012_embargoed_en.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Copp, R.; Kremmer, M.L.; Roca, E. Socially Responsible Investment in Market Downturns Implications for the Fiduciary Responsibilities of Investment Fund Trustees. Griffith Law Rev. 2010, 19, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, K.; Pohl, J. Environmental Concerns in International Investment Agreements: A Survey; OECD Working Papers on International Investment 2011/01; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/WP-2011_1.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Ikenberry, G.J. The End of Liberal International Order? Int. Aff. 2018, 94, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggie, J.G. International Regimes, Transactions, and Change: Embedded Liberalism in the Postwar Economic Order. Int. Organ. 1982, 36, 379–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.; Keohane, R. Ideas and Foreign Policy: An Analytical Framework; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1993; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Ikenberry, G.J. The Future of the Liberal World Order: Internationalism after America. Foreign Aff. 2011, 90, 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rajput, A. Regulatory Freedom and Indirect Expropriation in Investment Arbitration; Kluwer Law International BV: Zuid-Holland, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2020: International Production beyond the Pandemic. p. 219. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2020_en.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Zarsky, L. Introduction: Balancing Rights and Rewards in Investment Rules. In International Investment for Sustainable Development: Balancing Rights and Rewards; Zarsky, L., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, X. Environmental and Human Rights Counterclaims in International Investment Arbitration: At the Crossroads of Domestic and International Law. J. Int. Econ. Law 2021, 24, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations General Assembly. Resolution A/76/L.75 The Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment. 26 July 2022. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/LTD/N22/436/72/PDF/N2243672.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Alvarez, J.E. Critical Theory and the North American Free Trade Agreement’s Chapter Eleven. Univ. Miami Inter-Am. Law Rev. 1996, 28, 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Brower, C.H., II. NAFTA’s Investment Chapter: Initial Thoughts About Second-Generation Rights. Vanderbilt J. Transnatl. Law 2003, 36, 1533–1566. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy, P.-M. Unification Rather than Fragmentation of International Law? The Case of International Investment Law and Human Rights Law. In Human Rights in International Investment Law and Arbitration; Dupuy, P.-M., Petersmann, E.-U., Francioni, F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Steininger, S. What’s Human Rights Got to Do with It? An Empirical Analysis of Human Rights References in Investment Arbitration. Leiden J. Int. Law 2018, 31, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahner, J.H.; Happold, M. The Human Rights Defence in International Investment Arbitration: Exploring the Limits of Systemic Integration. Int. Comp. Law Q. 2019, 68, 741–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potestà, M. Mapping Environmental Concerns in International Investment Agreements. In Foreign Investment, International Law and Common Concerns; Treves, T., Seatzu, F., Trevisanut, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Viñuales, J.E. Foreign Investment and the Environment in International Law; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tropper, J.; Wagner, K. The European Union Proposal for the Modernisation of the Energy Charter Treaty—A Model for Climate-Friendly Investment Treaties? J. World Invest. Trade 2022, 23, 813–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaukrodger, D. The Future of Investment Treaties: Background Note on Potential Avenues for Future Policies. In OECD Working Papers, Proceedings of the 6th Annual Conference on Investment Treaties, Virtual Conference, 29–30 March 2021; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/investment-policy/Note-on-possible-directions-for-the-future-of-investment-treaties.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Tienhaara, K. Regulatory Chill in a Warming World: The Threat to Climate Policy Posed by Investor-State Dispute Settlement. Transnatl. Environ. Law 2018, 7, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tienhaara, K.; Downie, C. Risky business? The Energy Charter Treaty, Renewable Energy, and Investor-state Disputes. Glob. Gov. Rev. Multilater. Int. Organ. 2018, 24, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, A. The Management of Protected Areas of International Significance. N. Z. J. Environ. Law 2006, 10, 93–128. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, L.E.; Gray, K.R. International Human Rights in Bilateral Investment Treaties and in Investment Treaty Arbitration, International Institute for Sustainable Development (Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs 2003). Available online: https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/investment_int_human_rights_bits.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Wu, M.; Salzman, J. The Next Generation of Trade and Environment Conflicts: The Rise of Green Industrial Policy. N. Univ. Law Rev. 2014, 108, 401–474. [Google Scholar]

- Titi, C. The Righ to Regulate. In Foreign Investment Under the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA); Mbengue, M.M., Schacherer, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 159–183. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, L.L. In Need of a Paradigm Shift: Reimagining Eco Oro v Colombia in Light of New Treaty Language. J. World Invest. Trade 2022, 23, 915–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, T. Modification of Renewable Energy Support Schemes Under the Energy Charter Treaty: Eiser and Charanne in the Context of Climate Change. Goettingen J. Int. Law 2017, 8, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Lavranos, N.; Investment Arbitration and Environmental Protection: A Double-Edged Sword. 9 November 2015. Available online: https://arbitrationblog.kluwerarbitration.com/2015/11/09/investment-arbitration-and-environmental-protection-a-double-edged-sword/ (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Gantz, D.A. Increasing Host State Regulatory Flexibility in Defending Investor-State Disputes: The Evolution of U.S. Approaches from NAFTA to the TPP. Int. Lawyer 2017, 50, 231. [Google Scholar]

- OHCHR. Promotion of a Democratic and Equitable International Order; Commission on Human Rights Resolution 2001/65; OHCHR: Geneva, Switzerland, 25 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kube, V.; Petersmann, E.-U. Human Rights Law in International Investment Arbitration. In General Principles of Law and International Investment Arbitration; Gattini, A., Tanzi, A., Fontanelli, F., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 221–268. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, W. Realizing the Right to Water in International Investment Law: An Interdisciplinary Approach to BIT Obligations. Nat. Resour. J. 2008, 48, 431–478. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, M. The Sociology of International Investment Law. In The Foundations of International Investment Law: Bringing Theory into Practice; Douglas, Z., Pauwelyn, J., Viñuales, J.E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. The Protection of Legitimate Expectations as a ‘General Principle of Law’: Some Preliminary Thoughts. Transnatl. Disput. Manag. 2009, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W. China’s Foreign Investment Law in the New Normal: Framing the Trajectory and Dynamics; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; p. 719. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2021: Investing in Sustainable Recovery. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2021_en.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Johnsons, C. MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Japanese Industrial Policy 1925–1975; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Freidman, D. The Misunderstood Miracle: Industrial Development and Political Change in Japan; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Scalapino, R.A.; Sato, S.; Wanandi, J. (Eds.) Asian Economic Development: Past and Future; Institute of East Asian Studies: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Haggard, S. Pathways from the Periphery: The Politics of Growth in the Newly Industrialized Countries; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ann, L.S. Industrialization in Singapore; Longman’s: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Yah, L.C. Economic Restructuring in Singapore; Federal Publication: Washington, DC, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, J.-E. Race to the Swift: State and Finance in Korean Industrialization; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, T.B. Entrepreneurs, Multinationals and the State. In Contending Approaches to the Political Economy of Taiwan; Winckler, E.A., Greenhalgh, S., Eds.; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 175–205. [Google Scholar]

- Gries, P.H. China’s New Nationalism: Pride, Politics, and Diplomacy; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S. We Are Patriots First and Democrats Second: The Rise of Chinese Nationalism in the 1990s. In What If China Doesn’t Democratize? Implications for War and Peace; Friedman, E., McCormick, E., McCormick, B., Eds.; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality and Species Membership; Belknap Press Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Developments as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- United States Trade Representative, Report to Congress on China’s WTO Compliance. 2005. Available online: https://china.usc.edu/sites/default/files/article/attachments/2005%20China%20Report%20to%20Congress.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Environment Directorate of the OECD. Environmental Performance Review of China; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwati, J. India’s Reform and Growth Have Lifted All Boats. Financial Times, 1 December 2010; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, J. Sen Warns that India’s Growth Must Not Come at Price of Food. Financial Times, 22 December 2010; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pilling, D. Nature Will Constrain China’s Growth. Financial Times, 4 October 2010; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. China Must Continue the Momentum of Green Law. Nature 2014, 509, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Z.; Bu, S.; Xue, B. Environmental Legislation in China: Achievements, Challenges and Trends. Sustainability 2016, 6, 8967–8979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Cao, C.; Gu, J.; Liu, T. A New Environmental Protection Law, Many Old Problems? Challenges to Environmental Governance in China. J. Environ. Law 2016, 28, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Guo, H. Does Central Supervision Enhance Local Environmental Enforcement? Quasi-experimental Evidence from China. J. Public Econ. 2018, 164, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.-A. Environmental Grants and Regulations in Strategic Farm Business Decision-making: A Case Study of Attitudinal Behaviour in Scotland. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, J.; Huang, X.; Sun, S.; Hao, Y.; Wu, H. How Does New Environmental Law Affect Public Environmental Protection Activities in China? Evidence from Structural Equation Model Analysis on Legal Cognition. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 714, 136558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X. Environmental Protection Related to Chinese Overseas Investments: An Investigation from the Dimension of Investment Law. J. Xiamen Univ. (Arts Soc. Sci.) 2018, 247, 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn, D.H. The Environmental Impact of China’s Investment in Africa. Cornell Int. Law J. 2016, 49, 25–68. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, J. Supplying the World’s Factory: Environmental Impacts of Chinese Resource Extraction in Africa. Tulane Environ. Law J. 2015, 28, 393–408. [Google Scholar]

- Weeramantry, J.R. Treaty Interpretation in Investment Arbitration; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X. On the Environmental Rules in U.S. Investment Treaties and Their Implications for China. Stud. Law Bus. 2013, 30, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

| Surveyed IIAs | IIAs with Environment Clauses in Preambles | IIAs with Environment Clauses (Except Preambles) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 2584 | 147 | 323 |

| Percentage (vs. the Surveyed IIAs in total) | 100.00% | 5.69% | 12.50% |

| Example | N/A | China-Japan-Korea, Republic of Trilateral Investment Agreement (2012), Preamble para 5: “Recognizing the importance of investors’ complying with the laws and regulations of a Contracting Party in the territory of which the investors are engaged in investment activities, which contribute to the economic, social and environmental progress; ……” | ASEAN-Hong Kong SAR Investment Agreement (2017), Annex 2, Article 4: “Non-discriminatory regulatory actions by a Party that are designed and applied to achieve legitimate public welfare objectives, such as the protection of public health, safety, and the environment, do not constitute expropriation of the type referred to in subparagraph 2 (b)”. |

| Surveyed IIAs | IIAs with Environment Clauses in Preamble | IIAs in which Parties Commit Not to Lower Environmental Standards | IIAs with Environmental Exceptions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 2584 | 147 | 123 | 243 |

| Percentage (vs. the Surveyed IIAs in total) | 100.00% | 5.69% | 4.76% | 9.40% |

| Type of Provisions | Example | Content | Treaty Duty (by Investors or States) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Preservation of States’ Regulatory Power | China-Singapore BIT (1985) | Article 11 “Prohibitions and Restrictions”: “The provisions of this Agreement shall not in any way limit the right of either Contracting Party to apply prohibitions or restrictions of any kind or take any other action which is directed to the protection of its essential security interests, or to the protection of public health or the prevention of diseases and pests in animals or plants”. | N/A |

| The Recognition of Environmental Protection as Treaty Objective | U.S. Model BIT (2012) | Preamble para 5: “Desiring to achieve these objectives in a manner consistent with the protection of health, safety, and the environment, and the promotion of internationally recognized labor rights; ……” | States |

| The States’ Continuing Duty to Take Environmental Protection Measures | Canada-Hong Kong SAR BIT (2016) | Article 15 “Health, Safety and Environmental Measures”: “The Parties recognize that it is inappropriate to encourage investment by relaxing their health, safety or environmental measures. Accordingly, a Party should not waive or otherwise derogate from, or offer to waive or otherwise derogate from, those measures to encourage the establishment, acquisition, expansion or retention in its area of an investment of an investor. ……” | States |

| The Investor and Investment’s Obligation related to Environmental Protection | The Netherlands Model BIT (2019) | Section 3, Article 7 para 1: “Investors and their investments shall comply with domestic laws and regulations of the host state, including laws and regulations on human rights, environmental protection and labor laws”. | Investors |

| Year of Initiation | Case Name (In Brief) | Relevant Treaty & Provisions (If Data Available) | Summary of Claims | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Ethyl v. Canada | NAFTA (1992) & Indirect expropriation, national treatment, performance requirements | Claims arising out of a Canadian regulation concerning of the gasoline additive MMT imports. | Settled |

| 1999 | Methanex v. USA | NAFTA (1992) & Indirect expropriation, fair and equitable treatment, national treatment | Claims arising out of damages caused by a state-level ban on the use or sale of the gasoline additive in California. | Decided in favour of the state |

| 2003 | Inceysa v. El Salvador | El Salvador–Spain BIT (1995) & Indirect expropriation | Claims arising out of the decision of El Salvador’s Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources not to fulfill a concession contract of vehicle inspection, previously awarded to the investor. | Decided in favour of the state |

| 2007 | Global Gold Mining v. Armenia | Armenia–United States of America BIT (1992) & Indirect expropriation, fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security | Claims arising out of the decision of Armenia’s Ministry of Environment to deny the investor’s renewal of existing mining licenses and the granting of new licenses. | Settled |

| 2008 | Mercuria Energy v. Poland (I) | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Indirect expropriation, fair and equitable treatment | Claims arising out of the host state’s implementation of a EU’s Directive calling for an increase of fuel reserves and the negative impact of such implementation upon the claimant’s subsidiary operating the importation of fuel. | Decided in favour of the state |

| 2008 | Oeconomicus v. Czech Republic | Czech Republic–Switzerland BIT (1990) | Claims arising out of the refusals to honour guarantees made by the Environment Ministry to the claimant’s investment. | Discontinued |

| 2009 | Abengoa v. Mexico | Mexico–Spain BIT (2006) & Indirect expropriation, fair and equitable treatment | Claims arising out of the stalled opening of the claimant-built waste landfill and treatment plant in Mexico, due to several acts by the municipal government and certain federal authorities. | Decided in favour of the investor |

| 2009 | Gold Reserve v. Venezuela | Canada–Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic of BIT (1996) & Indirect expropriation, fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security, most-favoured nation treatment | Claims arising out of the host state’s deprivation of the investor’s rights in certain mining project in Venezuela, led by an administrative ruling by the Ministry of Environment declaring the nullity of relevant permit and the termination of investor’s concessions. | Decided in favour of the investor |

| 2011 | Mamidoil v. Albania | Albania-Greece BIT (1991), The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security, indirect expropriation | Claims arising out of the host state’s decision to relocate investor’s operations after the government planning to establish a tank farm as a non-industrial zone in the relevant area, and other governmental measures aimed to ban the use of the investor’s fuel deposits, the investments’ operation, and the supply of the fuel tank farm. | Decided in favour of the state |

| 2011 | Mesa Power v. Canada | NAFTA (1992) & Fair and equitable treatment, national treatment, most-favoured nation treatment, performance requirements, full protection and security | Claims arising out of the host state’s measures concerning the renewable energy regulation in a Canadian province, which imposed unexpected changes to the established feed-in-tariff program regime. | Decided in favour of the state |

| 2011 | The PV Investors v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security | Claims arising out of several energy reforms imposed by the host state concerning renewable energy, including the subsidy reduction for relevant energy generators and the tax imposed on the power producers’ revenues. | Decided in favour of the investor |

| 2011 | Baggerwerken v. Philippines | BLEU (Belgium–Luxembourg Economic Union)–Philippines BIT (1998) | Claims arising out of the host state’s sudden termination of a contract entered into by the previous administration with the investor for the lake rehabilitation aiming to improve the ecological condition. | Decided in favour of the investor |

| 2013 | Antaris and Göde v. Czech Republic | Germany–Slovakia BIT (1990), The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security | Claims arising out of amendments to the pre-existing incentive regime for the renewables, including the imposition of tax on electricity generated. | Decided in favour of the state |

| 2013 | Europa Nova v. Czechia | Cyprus–Czech Republic BIT (2001), The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security | Decided in favour of the state | |

| 2013 | I.C.W. v. Czechia | Czech Republic–United Kingdom BIT (1990), The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security | Decided in favour of the state | |

| 2013 | JSW Solar and Wirtgen v. Czech Republic | Czech Republic–Germany BIT (1990) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security, umbrella clause | Decided in favour of the state | |

| 2013 | Natland and others v. Czech Republic | Czech Republic–Netherlands BIT (1991), Cyprus–Czech Republic BIT (2001), BLEU-Czech Republic BIT (1989), The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security | Pending | |

| 2013 | Photovoltaik Knopf v. The Czech Republic | Czech Republic–Germany BIT (1990), The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security | Decided in favour of the state | |

| 2013 | Voltaic Network v. Czechia | Czech Republic–Germany BIT (1990), The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security | Decided in favour of the state | |

| 2013 | ASA v. Egypt | Egypt–Italy BIT (1989) | Claims arising out of the host state’s measures affecting the investor’s investment in a company which had entered contracts for waste treatment in Cairo. | Settled |

| 2013 | EVN v. Bulgaria | Austria–Bulgaria BIT (1997); The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Claims arising out of measures by the host state authorities and government agencies in relation to the pricing of power and compensation concerning renewable energy. | Decided in favour of the state |

| 2013 | CSP Equity Investment v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Indirect expropriation, fair and equitable treatment | Claims arising out of several energy reforms imposed by the host state concerning renewable energy, including the subsidy reduction for relevant energy generators and the tax imposed on power producers’ revenues. | Decided in favour of the state |

| 2013 | Eiser and Energía Solar v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, umbrella clause, indirect expropriation | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2013 | Infrastructure Services and Energia Termosolar (formerly Antin) v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, umbrella clause | Decided in favour of the state | |

| 2013 | Isolux v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Decided in favour of the state | |

| 2013 | RREEF v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, Umbrella clause | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2014 | InfraRed and others v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security, indirect expropriation, umbrella clause | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2014 | Masdar v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2014 | NextEra v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, most-favoured nation treatment, umbrella clause | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2014 | RENERGY v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, umbrella clause, full protection and security, indirect expropriation | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2014 | RWE Innogy v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, umbrella clause | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2015 | 9REN Holding v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, indirect expropriation, umbrella clause | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2015 | Alten Renewable v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment | Discontinued | |

| 2015 | BayWa r.e. v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Indirect expropriation, umbrella clause, full protection and security, fair and equitable treatment | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2015 | Cavalum SGPS v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, indirect expropriation, umbrella clause | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2015 | Cube Infrastructure and others v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, indirect expropriation, umbrella clause | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2015 | E.ON SE and others v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Pending | |

| 2015 | Foresight and others v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, umbrella clause, indirect expropriation | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2015 | Hydro Energy 1 and Hydroxana v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Indirect expropriation, fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2015 | JGC v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2015 | Kruck and others v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, indirect expropriation | Pending | |

| 2015 | KS and TLS Invest v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Pending | |

| 2015 | Landesbank Baden-Württemberg and others v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Pending | |

| 2015 | Novenergia v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security, umbrella clause, indirect expropriation | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2015 | OperaFund and Schwab v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security, umbrella clause | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2015 | SolEs Badajoz v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, indirect expropriation, umbrella clause | Discontinued | |

| 2015 | Stadtwerke München and others v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, umbrella clause | Decided in favour of the state | |

| 2015 | Watkins and others v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, umbrella clause | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2015 | ENERGO-PRO v. Bulgaria | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994), Bulgaria-Czech Republic BIT (1999) | N/A | |

| 2016 | Biram and others v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2016 | Sevilla Beheer B.V. v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, umbrella clause | Pending | |

| 2016 | Eurus Energy v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Indirect expropriation, fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security | Decided in favour of the investor | |

| 2016 | Green Power and SCE v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Decided in favour of the state | |

| 2016 | Infracapital v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security, umbrella clause | Pending | |

| 2014 | Ballantine v. Dominican Republic | CAFTA–DR (2004) & National treatment, most-favoured nation treatment, fair and equitable treatment, indirect expropriation, full protection and security | Claims arising out of the rejection by the host state’s environmental authority to the investors’ request to expand their residential and tourism project, as well as other measures taken by the central and local authorities. | Decided in favour of the state |

| 2016 | ESPF and others v. Italy | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, umbrella clause | Claims arising out of several decrees to cut incentives for certain renewable power projects. | Decided in favour of the investor |

| 2017 | Elitech and Razvoj v. Croatia | Croatia–Netherlands BIT (1998) | Claims arising out of Croatia’s measures and actions leading to the stalled construction of a golf resort. The Croatian court’s rulings Reid to overturn the Croatian environmental ministry ’s approval of the resort’s construction. | Pending |

| 2017 | Tennant Energy v. Canada | NAFTA (1992) & Fair and equitable treatment | Claims arising out of the unfair treatment of the investor’s renewable power generating project through certain regulatory measures, and the local authority’s non-transparency of the feed-in tariff plan for renewable energy sources. | Pending |

| 2017 | FREIF Eurowind v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, umbrella clause | Claims arising out of several energy reforms imposed by the host state concerning renewable energy, including the subsidy reduction for relevant energy generators and the tax imposed on power producers’ revenues. | Decided in favour of the state |

| 2017 | Portigon v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Pending | |

| 2018 | KLS Energy v. Sri Lanka | Malaysia–Sri Lanka BIT (1982) | Claims arising out of the host state’s cancellation of a renewable energy generator project invested by the claimant. | Pending |

| 2018 | LSG Building Solutions and others v. Romania | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment | Claims arising out of several changes to the host state’s incentive scheme concerning renewable energy investment. | Pending |

| 2018 | European Solar Farms v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Claims arising out of several energy reforms imposed by the host state concerning renewable energy, including the subsidy reduction for relevant energy generators and the tax imposed on power producers’ revenues. | Pending |

| 2019 | Odyssey v. Mexico | NAFTA (1992) & National treatment, fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security, indirect expropriation | Claims arising out of the decision by Mexico’s environmental authority denying permits for the investor’s mining project. | Pending |

| 2019 | Mamacocha and Latam Hydro v. Peru | Peru-United States FTA (2006) & Fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security, indirect expropriation, umbrella clause | Claims arising out of the host state’s breach of a concession agreement for a renewable energy plant project by delaying to permit and approve it. | Pending |

| 2019 | Strabag and others v. Germany | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Claims arising out of the host state’s legislative changes concerning the renewable energy regime, including for power generation, which allegedly caused the investors to abandon relevant projects. | Pending |

| 2020 | EP Wind v. Romania | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Claims arising out of several changes to the host state’s incentive scheme concerning renewable energy investment. | Pending |

| 2020 | Fin.Doc and others v. Romania | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Pending | |

| 2021 | KELAG and others v. Romania | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment, indirect expropriation | Pending | |

| 2021 | RSE v. Latvia (II) | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) & Fair and equitable treatment | Claims arising out of the host state’s change of its renewable energy regulatory framework including relevant incentives programs. | Pending |

| 2021 | Spanish Solar v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Claims arising out of several regulatory changes undertaken by the host state affecting the renewables sector. | Pending |

| 2022 | WOC Photovoltaik and others v. Spain | The Energy Charter Treaty (1994) | Pending |

| Relevant Provisions in Chinese BITs | Relevant Provisions in Chinese TIPs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Environmental Protection” | “Sustainable Development” | “Environmental Protection” | “Sustainable Development” | |

| Treaty Principles and Objectives Content | 2 | 3 | 26 | 5 |

| Environmental Measure Clauses | 1 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Indirect Expropriation Clauses | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Exception Clauses | 3 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| No-jurisdiction Clause | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 12 | 3 | 43 | 5 |

| 15 | 48 | |||

| Contracting Party | Year | Number of Relevant Provisions | Content of Provisions (Including Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development Clauses) | Form of Provisions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey | 2015 | 2 | Environmental Protection | Exception Clause |

| Environmental Protection | Indirect Expropriation Clause | |||

| Tanzania | 2013 | 3 | Sustainable Development (CSR) | Treaty Principles and Objectives Contents |

| Environmental Protection | Environmental Measures Clause | |||

| Environmental Protection | Indirect Expropriation Clause | |||

| Canada | 2012 | 4 | Sustainable Development | Treaty Principles and Objectives Contents |

| Environmental Protection | Exception Clause | |||

| Environmental Protection | Indirect Expropriation Clause | |||

| Environmental Protection | No-jurisdiction Clause | |||

| Uzbekistan | 2011 | 2 | Sustainable Development | Treaty Principles and Objectives Contents |

| Environmental Protection | Indirect Expropriation Clause | |||

| Columbia | 2008 | 1 | Environmental Protection | Indirect Expropriation Clause |

| Guyana | 2003 | 1 | Environmental Protection | Treaty Principles and Objectives Contents |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 2002 | 1 | Environmental Protection | Treaty Principles and Objectives Contents |

| Mauritius | 1996 | 1 | Environmental Protection | Exception Clause (Article 11) |

| Total | 15 | - | ||

| TIP | Year | Number of Provisions | Content of Provisions (Including Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development Clauses) | Form of Provisions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCEP | 2020 | 2 | Environmental Protection | Indirect Expropriation Clause |

| Environmental Protection | Exception Clause | |||

| China–Cambodia FTA | 2020 | 4 | Environmental Protection | Environmental Measure Clauses (2) |

| Environmental Protection | Exception Clause | |||

| Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development | Treaty Principles and Objectives Contents | |||

| China–Mauritius FTA | 2019 | 2 | Environmental Protection | Exception Clause (Article 8.9 para 3(d)) |

| Environmental Protection | Indirect Expropriation Clause | |||

| Mainland and Hong Kong Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement | 2017 | 2 | Environmental Protection | Exception Clause |

| Environmental Protection | Environmental Measures Clause | |||

| China–Georgia FTA | 2017 | 1 | Environmental Protection | Treaty Principles and Objectives Contents |

| Australia–China FTA (ChAFTA) | 2015 | 3 | Environmental Protection | Exception Clause |

| Environmental Protection | No-jurisdiction Clauses (2) (Article 9.11 para 4) | |||

| China–Korea FTA | 2015 | 2 | Environmental Protection | Treaty Principles and Objectives Contents |

| Environmental Protection | Environmental Measures Clause | |||

| China–Swiss FTA | 2013 | 11 | Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development | Treaty Principles and Objectives Contents (6) |

| Sustainable Development | Treaty Principles and Objectives Contents (4) (Article 1.1 para 1) | |||

| Environmental Protection | Environmental Measures Clause | |||

| China–Iceland FTA | 2013 | 2 | Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development | Treaty Principles and Objectives Contents |

| China–Japan-Korea Trilateral Investment Agreement | 2012 | 2 | Environmental Protection | Treaty Principles and Objectives Contents |

| Environmental Protection | Environmental Measures Clause | |||

| China–Peru FTA | 2009 | 4 | Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development | Treaty Principles and Objectives in Preamble (3) |

| Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development | Environmental Measures Clause | |||

| China–New Zealand FTA | 2008 | 5 | Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development | Treaty Principles and Objectives in Preamble (4) |

| Environmental Protection | Exception Clause (Article 200 para 2) | |||

| China–Pakistan FTA | 2006 | 2 | Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development | Treaty Principles and Objectives in Contents |

| China–Chile FTA | 2005 | 2 | Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development | Treaty Principles and Objectives in Contents |

| Trade and Economic Framework Agreement between Australia and China | 2003 | 1 | Environmental Protection | Treaty Principles and Objectives in Contents |

| Mainland China and Macao Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement | 2003 | 1 | Sustainable Development | Treaty Principles and Objectives in Contents (Article 2 para 3) |

| Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Co-operation between the Association of South East Asian Nations and the People’s Republic of China | 2002 | 1 | Environmental Protection | Treaty Principles and Objectives in Contents |

| Agreement on Trade and Economic Cooperation between the European Economic Community and the People’s Republic of China | 1985 | 1 | Environmental Protection | Treaty Principles and Objectives in Contents |

| Total | 48 | - | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, K.; Shen, W. Environmental Protection Provisions in International Investment Agreements: Global Trends and Chinese Practices. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8525. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118525

Su K, Shen W. Environmental Protection Provisions in International Investment Agreements: Global Trends and Chinese Practices. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8525. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118525

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Kezhen, and Wei Shen. 2023. "Environmental Protection Provisions in International Investment Agreements: Global Trends and Chinese Practices" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8525. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118525