1. Introduction

While Internet-associated businesses have experienced more than two decades of implementing and advancing practical industrial models and strategic frameworks, such as those provided by Chaffey et al. [

1], Jelassi and Martinez-Lopez [

2], and Laudon and Traver [

3], most of these models were designed and established for conventional enterprises and normal brick-and-mortar firms. Currently, there is a lack of appropriate and sustainable industrial models that have proved to be perfectly suited to cultural and creative industry (CCI) firms, owing to these firms’ local, small-scale features and distinctive cultural and creative context [

4].

Furthermore, there is no doubt that the ceaseless spread of the coronavirus (

https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html, accessed on 10 April 2023) has gone down in history as the defining crisis of the period from 2020 to 2023, and perhaps beyond. Kessler [

5] (p. 55) proposed a term—the so-called New Normal—to describe the world in the wake of the pandemic; even if people’s lives return to normal, things will never be exactly the same as they were before. While the business opportunities for CCI firms will not disappear completely, this form of firm will invariably face new consumption patterns. Individuals can be anticipated to have a greater-than-ever demand for personalized and customized products, such as wall art or creative accessories, because of their long hours working at home, which will also give rise to novel demands for CCI products and services.

Since many CCI proprietors’ educational and training backgrounds were based on the prospects of becoming artists, craftspeople, or designers, the question of how to develop a successful industrial model and make sure that it comprehensively addresses the compulsory elements and activities has become a critical issue because it is related to the notions of the business sector [

6]. Furthermore, based on prior studies, many CCI proprietors have expressed that they do not have sufficient knowledge and the practical wherewithal to formulate appropriate business models for their firms, especially in the nascent, albeit gradually maturing, era of ubiquitous Internet access [

4,

7,

8].

In this context, the present article contends that the potential key elements for a cultural and creative industry (CCI) business model, as proposed by prior studies—namely cultural and creative value, market estimation, achievement of business benefits, and marketing leverage—appear to be insufficient when these elements are confronted by the distinctive features of CCIs. These features include a heightened level of risk associated with business activities, a focus on balancing creativity and commerce, high production costs versus low reproduction costs, and the semi-public nature of goods that necessitates the creation of scarcity. Consequently, this study poses a major research question: “What are the special key elements crucial for the construction of a business model that aligns with the unique characteristics of CCIs”?

This study aims to address this challenging issue by considering the key elements of a CCI business model in the form of a set of guidelines, drawing on the insights of proprietors of firms in the CCI realm. Moreover, the study hopes to draw further attention to and spur debates about the scope of culture and creativity since it seems to be the time to consider ‘business’ ideas for CCI firms and proprietors and go beyond the traditional concepts of ‘art’, ‘culture’, ‘craft’, and ‘novelty’.

This manuscript is organized as follows. First, the defining characteristics of the CCI and related notions, as well as potential key spheres of a business model designed especially for the post-pandemic era, are explored in depth. Second, the compounded research methods applied for data collection and analysis herein are illustrated at length. Third, the findings are reported based on the viewpoints of the current CCI proprietors by converging the results with the preceding literature. Finally, the article arrives at conclusions and advice on the implications for theory and practice.

4. Results and Discussions

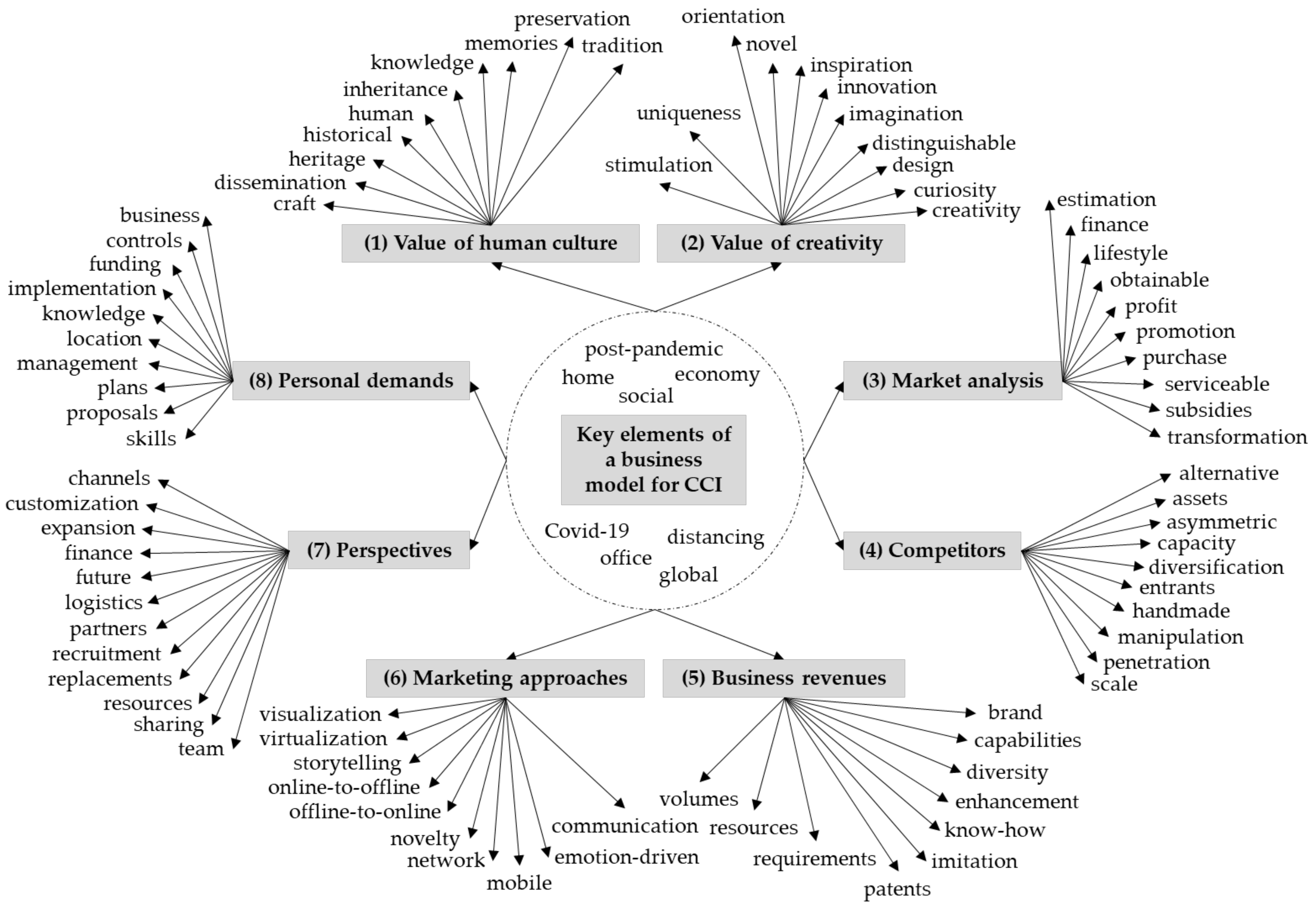

After the 54 informants’ opinions and comments were carefully extracted and considered, the content analysis revealed eight key elements for constructing a CCI business model. These key elements are categorized and elucidated below. Only those most valuable cases or descriptions were selected and are quoted.

- (1)

Statement of cultural value commitment

It was pointed out that many CCI products are not well embraced by their target markets because the business models underlying them lack one critical point: commitment to cultural value [

8]. A majority of the informants believed that the CCI products and services that they provide do, in fact, embody a certain degree of meaning in terms of cultural inheritance and civilization transmission.

For instance, as one respondent stated, ‘These woodblock printing products, which have encapsulated the cultural attributes and connotation of traditional craftsmanship for more than 1500 years, do inspire the customers’ spirits’ (Info04). Another expressed a similar sentiment in this way: ‘Based on a thousand years of hand-made pottery techniques, when I add some more artistic elements and modern expressions, my hand-made pottery products contain a combination of cultural connotations and practical functions’ (Info12). A third respondent noted, ‘Knitted products are definitely a type of commodity that could convey ideology, cultural symbols and lifestyles…In essence, it is a product that can affect and stimulate people’s thoughts’ (Info15).

When a CCI product has been imbued with cultural significance, and the techniques required to make them are based on a long-ago period, it seems that these products can surely improve people’s state of mind and their emotional states. The second informant—Info12—shared a similar sentiment about hand-made pottery products. The proprietor believed that the pottery offers a combination of cultural significance and practical use after artistic elements and modern expressions are incorporated. Furthermore, the third informant believed that knitted products can convey ideology, cultural symbols, and even lifestyles. These knitted products may be able to affect and stimulate people’s thoughts and therefore have a deeper significance beyond merely being a commodity. These expressions extended the concept from the prior literature of how important it is to embed cultural values into CCI products and services [

4,

13,

18,

19].

- (2)

Explication of added creativity values for CCI products

This sphere represented the notion that the CCI proprietors ought to manifest their original thinking, encompassing their belief in the worth, utility, and creativeness of their products and services. The prior literature has proposed a ‘cultural product design model’ for designing and adding the spirit and value of creativity to cultural products [

50]. In the course of the interviews conducted in this study, two informants’ responses stood out as examples of this idea. The first one referred to combining the energy of jade with hand sanitizer. In the informant’s words: ‘

I realize everyone has a demand to clean their hands during the pandemic. Therefore, I told consumers that jade has the function of increasing energy, which seems triggered their emotions to try new things besides hygiene protection. Surprisingly, the hand sanitizers with jade are becoming popular online’ (Info27). The second one referred to the far-infrared rays emitted by bamboo charcoal derivative, which can promote metabolism and eliminate fatigue: ‘

…during the most serious pandemic period, this product was searched online and purchased every day, as it seems many people were looking for things that can provide protection’ (Info31). Creativity seemed to be implemented in the right circumstances with the right causes, especially during the pandemic.

Although the marketing strategies were also addressed in the above examples, both of the proprietors acknowledged that it was important to apply their creativity to appeal to people’s emotions and desire for something more than simply basic hygiene protection. By emphasizing the function of those products in increasing energy, they were able to pique the interest of consumers and encourage them to try something new. Originally, it may have been difficult for consumers to relate jade ornaments or bamboo charcoal derivatives to the pandemic. However, when the distinctive characteristics of the CCI products were clarified, consumers could be encouraged to experience the uniqueness of the products or services. The idea of ‘added creativity value’ for CCI product development has also extended the concepts of ingenuity, curiosity, and adventure provided by previous literature [

6,

9,

51].

- (3)

CCI products and services marketplace conjecture

This sphere related to the onus on CCI firms to envision the market ranges of their products or services, including actual and/or potential commercial value areas. Additionally, it also represented the important concept of mapping different levels of product and service ranges to different levels of market areas. One respondent replied, ‘I was not sure that Hemerocallis fulva had beauty benefits until the facial mask manufacturer told me about this. And this gave me a new way out…It allowed me to start reforming my business strategy for approaching diversified businesses’ (Info02). Another respondent portrayed the concept in this way: ‘Since the price of hand-made wooden lamps can range from several thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars, I have established different levels of products, especially for those customized products’ special prices and their focused market scopes’ (Info34).

The first informant—Info02—discovered the beauty benefits of

Hemerocallis fulva (a type of flower that is also edible) after being informed about them by a facial mask manufacturer. This information allowed the proprietor to explore new possibilities and reform the business strategy to include a more diverse range of products. The second respondent attempted to establish different levels of products to cater to different markets, especially those looking for customized products at special prices. By doing so, the firm was able to offer a wider range of products to different customers and, furthermore, could focus on specific markets to maximize profits. These valuable narratives were consistent with the thoughts about market estimations expressed in the literature [

23] but from new perspectives, and they provided evidence for the feasibility of CCI firms using the concept of market range prediction to transform themselves.

- (4)

Analyses of direct and indirect trading competitors

This sphere referred to the other firms being able to sell similar products and operate in the same marketplace. It also recognized the existence of alternative products and potential new entrants into the CCI market. On the other hand, while some companies may be in different industries, their products can still be substitutes for each other. As one respondent expressed this dilemma: ‘My handmade bags and purses are seriously affected by this pandemic because the local market fairs did not open, nor did any of the holiday markets. Although I have tried to reduce the prices of my products, the companies that have online stores and continue to operate virtually have more competitive capability than I do’ (Info05). Yet another proprietor observed, ‘… those medium-size or big companies do have their competitive advantages and can make more profits from their products. Even though each of my handmade bags is unique, and I never duplicate any of them, the bag market is still very competitive’ (Info33).

Actually, many informants discussed the negative impact of the pandemic on their businesses selling handmade products, including Info08, 11, 13, 17, 20, 21, 22, 24, 33, and 45. Because of the closure of local markets and holiday markets, they have not been able to sell their products. They attempted to reduce the prices of their products but still struggled to compete with companies that have online stores and can operate virtually. Both informants highlighted the challenge of being a small business owner during the pandemic. Furthermore, the second informant acknowledged that, despite the uniqueness of the store’s handmade bags, the bag market was still very competitive. The CCI firms seemed to have few viable advantages that could bring more revenues from their products. These narratives pointed out that analysis of the current environment might help the proprietors to grasp the actual situation, and if there are many similar companies in a specific industrial field, it will be difficult to make a profit [

11,

17,

24].

- (5)

Tactics for acquiring industrial profits

This sphere considered distinct factors of production that other firms cannot easily access, at least in the short term. One of the keys to obtaining benefits was whether the CCI firms had the specialized skills and specific knowledge required to produce products that other companies lack. One informant explained, ‘Recently, I developed a new type of product, which embedded scallop shells on wooden pen holders. This is because a lot of wood has some chips in it; I inserted these shell fragments to fill up the indentations before it is made into a penholder so that some part of the penholder shines with the brilliance of the shell. And it’s now one of my staples, selling really well’ (Info28). Another proprietor said, ‘We added aboriginal totems to the base of the wooden clocks, and now even for customized clocks, some customers request that we add these aboriginal elements to them’ (Info29).

Informant Info28 embedded scallop shells into wooden pen holders to fill up the indentations in the wood and created a unique design element that catches the eye. This innovation became a staple for the informant’s business and was selling well. It was a clever product development strategy to differentiate CCI hand-made products and increase value by adding a distinctive and visually appealing element. According to Info29′s opinion, when the local firm added aboriginal totems to the base of the wooden clocks and provided a customized design, customers acknowledged that they had become a desirable feature of the product. The informants above seemed to have recognized the value of incorporating cultural elements into their product design, which may help to appeal to a broader customer base and differentiate their products from others in the market.

In terms of benefits, a third respondent stated, ‘

When the brand is established, consumers really remember my brand and introduce my products to others’ (Info27). The informant highlighted the benefits of establishing a brand for the CCI firm. Info27 mentioned that, once a brand was established, consumers might remember it and were more likely to introduce the products to others. This finding indicated that the informants, including Info08, 17, 20, 27, 45, and 54, recognized the importance of building a strong brand identity and the potential impact it can have on customer loyalty and word-of-mouth marketing. By focusing on branding, the respondent was likely investing in building a lasting and recognizable image for the products, which could result in standing out in a crowded marketplace and building a loyal customer base. These descriptions echoed sentiments expressed in the prior literature [

8,

31,

36] but extended evidence from the policies of CCI firms that developing unique features for products and services does bring them more industrial benefits.

- (6)

Marketing strategies for CCI products and services

How to sell ‘connotation’ and ‘creativity’ and create a positive value exchange system is key to the industrialization of cultural creativity [

36]. Almost all the interviewees mentioned that they knew it was crucial for addressing germane marketing issues. However, one interviewee confessed, ‘

During the pandemic period, the Internet seems to have become very important. But I really have no idea how to market my traditional stone carving products through the Internet’ (Info11). Another lamented, ‘

I know I need to combine the Internet and social media to do those marketing things, so I have opened a Facebook fan page…. Nevertheless, I really do not understand how to present the content…some friends said I need to talk about something related to my tea to touch people’s hearts. But the truth is, I am a farmer, and I really have no idea about how to tell good stories’ (Info01). Yet another respondent expressed bewilderment: ‘

When I saw some marketing gurus talking about the 4Ps or 7Ps, I was already spinning dizzily with confusion’ (Info42). The heightened role of a CCI firm’s online presence during the pandemic is undeniable, yet a lack of technical knowledge held many firms back: ‘

…when they all don’t want to go outside due to the pandemic, I certainly hope to help my customers to have a good view of my hand-made pottery works from their end via the Internet, but I don’t know how to do this’ (Info14).

These four informants all expressed a sense of confusion or frustration around using the Internet and social media for marketing their traditional crafts or products. The first informant—Info11—recognized the importance of the Internet but was unsure how to market the stone carving products online. Info01 created a Facebook fan page but did not know how to present content that would resonate with people. Info42 was overwhelmed by marketing jargon, such as the 4Ps or 7Ps, which are concepts related to product marketing. The fourth informant selected here acknowledged the need to showcase pottery online but lacked the technical knowledge to do so effectively. Overall, many informants, including Info11, 12, 14, 15, 17, 20, 30, 33, 37, 42, 46, 47, 48, 51, 53, and 54, suggested that, while they recognized the importance of online marketing during the pandemic, they still faced a lack of understanding and technical expertise regarding how to operate digital channels effectively. This fact highlighted the need for education and resources to support traditional craftspeople and small business owners in leveraging online tools for marketing and sales. As these comments illustrated, most of the proprietors who participated in this study expressed some level of frustration, especially during the pandemic period. Although some cases [

11] have reported similar findings, it is understood that the marketing strategies for CCI products or services typically fall outside the established boundaries and value structures of mainstream industries [

36].

- (7)

Future commerce development plans

This sphere considered the need for long-term expansion when some informants expressed that, because they operated personal studios or had only very few employees, they normally did not have a research and development (R&D) department in their firms, which many enterprises and normal brick-and-mortar companies have. The concept of this sphere represented most of the proprietors’ demands for advancements and additional arrangements. It was one of the two new dimensions found. However, two special cases should be reported. One interviewee remarked, ‘…actually, the pandemic did not distress me a lot because my raw jade ore came from my parents’ stocks. This period gave me some more time to rethink how to develop new products and find new consumer groups’ (Info27). Another described the situation in these terms: ‘… in fact, the pandemic did not really affect me or my business because, firstly, I still have a lot of wood in stock. Secondly, when customers did not visit the store, I regarded the daily making of these wooden pens as a new practice for my techniques. Moreover, I have already sketched out the ideas of the new styles that I would like to develop next year and the year after’ (Info28).

These two interviewees seemed to have a positive outlook on their situation during the pandemic. The first interviewee used the pandemic period to develop new products and find new consumer groups. This process showed that the interviewee had a long-term perspective on the business and was using this time to strategize and plan for the future. Info28 also used the pandemic period to practice and improve personal techniques and plan for future product development, showing a strong commitment to the craft. The study regarded these dialogues as a conspicuous decipherment. Nonetheless, during the interview processes, most of the informants (such as Info05, 15, 17, 20, 21, 24, 30, 40, 48, 49, 52) admitted that they knew future development plans were important, but when facing daily work and family matters and without systematic guidance about forming an appropriate future commerce development plan, especially based on the distinctive cultural and creative contexts, they felt frustrated. There are very few prior studies addressing this angle [

29].

- (8)

Requisite knowledge and skills for cultural business management

This sphere was another new one revealed by this study. Since most proprietors of CCIs conduct their businesses independently, they were required to enhance their management knowledge and skills continually. One particularly salient example appeared from the interviews: ‘I spent half of a year and drove four hours every weekend to a private class to learn relevant business operations and management knowledge and skills. The most interesting thing was that the lecturer also taught us about how to formulate a unique business model for ourselves’ (Info27). Other informants in this study also expressed that they urgently needed to engage in further studies to learn related expertise, including selecting a store’s location, developing business proposals, building the capacity to request funding from private/governmental sources, cultivating commerce management skills, bolstering competence to implement marketing activities, strengthening financial controls, etc. (Info01, 02, 11, 13, 30, 33, 45, 52).

Many informants addressed the importance of learning business operations and acquiring management knowledge and skills for creative industry entrepreneurs. In a special case, an interviewee spent half a year attending private classes and driving four hours every weekend to learn such skills and knowledge, including formulating a unique business model. However, others expressed the need to engage in further studies to gain related business management expertise. The interviewee responses suggested that many small and local creative businesses feel the need to acquire additional knowledge and skills related to business operations and management. This need is particularly urgent in light of the challenges brought about by the pandemic. The respondents recognized that, to stay competitive, they needed to learn how to select the right locations for their stores, develop business proposals, access funding, manage finances effectively, and implement marketing activities. These opinions expanded the results of prior literature [

52] and pointed to the importance of CCI proprietors taking steps to advance their knowledge and skills.

6. Conclusions

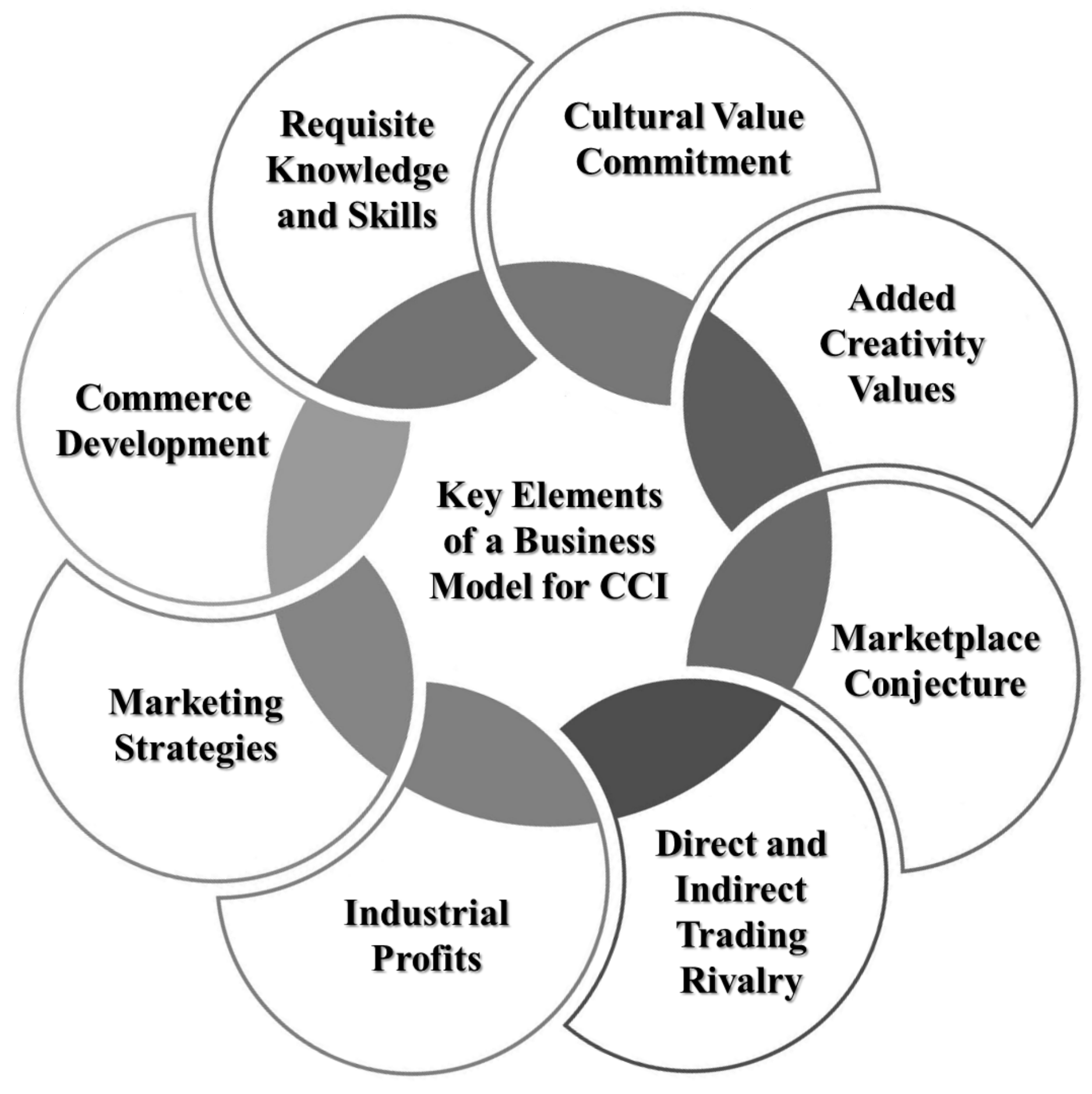

The current study used a set of key elements with a view toward helping proprietors in the cultural and creative industries (CCIs) to formulate appropriate business models based on the opinions and insights of experienced frontline proprietors of CCIs. This research has two vital implications for theory. First, it meets the urgent demand for guidance on how to operate and manage a CCI firm that is small-scale and has a low level of market identification in the post-pandemic era. It bears noting that many CCI firms are home-based, which means that proprietors conduct their businesses from their personal abodes, rather than working out of offices or storefronts. Generally speaking, these CCI proprietors have been facing the following obstacles: poor credit; excessive reliance on their personal management capability; difficulty in determining business performance; short product life cycles; insufficient innovation capability and IT investment; unclear marketing strategies; and difficulties in developing different marketing channels. The relationship between the identified obstacles and the proposed elements has been made explicit. Specifically, the obstacle of ‘poor credit’ could be mitigated by the effective implementation of “tactics for acquiring industrial profits”. Successful execution of these tactics could potentially improve the financial standing of the business and thus its access to credit. The issue of “excessive reliance on personal management capability” can be addressed by emphasizing “requisite knowledge and skills for cultural business management”. By enhancing this knowledge and skills, proprietors could be better equipped to delegate and manage more effectively. Furthermore, the challenge of “difficulty in determining business performance” can be directly tied to “CCI products and services marketplace conjecture” and “analyses of direct and indirect trading rivalries”. Both elements can provide clear parameters and metrics for performance evaluation.

“Short product life cycles” present a challenge that can be mitigated by “explication of added creativity values for CCI products” and “future commerce development plans”. By understanding the creative value of their products and having clear future plans, proprietors can devise strategies to extend their product life cycles. In addition, “insufficient innovation capability and IT investment” can be addressed by a “statement of cultural value commitment” and “future commerce development plans”. A strong commitment to cultural value and a well-structured plan for commerce development can stimulate innovation and justify IT investments. The obstacle of “unclear marketing strategies” can be directly addressed by the element of “marketing strategies for CCI products and services”, which aims to provide a clear and effective marketing roadmap. The issue of “difficulties in developing different marketing channels” can also be mitigated by the “marketing strategies for CCI products and services” element, suggesting suitable marketing channels for the industry. Each of the proposed eight elements for constructing a CCI business model directly corresponds to one or more of the identified obstacles, providing a comprehensive framework for addressing these challenges.

Second, because the current literature remains relatively ambiguous on the topic of how CCI firms can formulate appropriate and efficient business models, the eight key elements have not been discussed thoroughly in the prior literature, creating a particular dearth of deep-level investigations using qualitative research methods. Fortunately, thanks to the results of this study, there now exists a clearer blueprint for constructing workable business models for CCIs.

The eight spheres, as discussed previously, differ to some extent from those expounded in the prior literature and from the theories presented by CCI scholars. The present study endeavors to bridge an essential knowledge gap that exists between the cultural and creative industry (CCI) and business development and industrial operations, particularly in the context of the global COVID-19 pandemic. The research’s implications extend beyond theoretical understanding, shedding light on practical strategies to stimulate growth and employment opportunities in the CCI sector, which is of substantial socio-economic value. Specifically, the outcomes of the research offer explicit guidance for CCI proprietors seeking to enhance community well-being, leverage local cultural elements for industrial development, and apply these elements in a manner that generates added value. The insights derived from this study can serve as a robust foundation that supports these endeavors, consequently leading to the growth and resilience of CCIs. Furthermore, these elements are expected not only to have practical implications for current businesses in the CCI sector but also to instigate a positive cycle of scholarly and policy discussions. They can potentially inform and drive forward multidisciplinary cultural policies, highlighting their roles in managing the unique challenges faced by the CCI sector.

In conclusion, the scientific value of this research lies in its contribution to the existing body of knowledge on CCIs and their business development strategies during crisis times, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, its practical value is inherent in the specific guidance that it provides to CCI proprietors and the broader cultural policy discussions that it fosters. Through continuous exploration and implementation of the proposed key elements, we can facilitate sustainable and resilient development of the CCI sector amidst evolving global circumstances.