Gaps between Attitudes and Behavior in the Use of Disposable Plastic Tableware (DPT) and Factors Influencing Sustainable DPT Consumption: A Study of Hong Kong Undergraduates

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Questions

2.1. Attitude Formation Process

2.2. Disposable Plastic Tableware, Environmental Impact, and Public Attitudes

2.3. Sustainability Measures of Some Developed Countries and Regions and the Hong Kong Status Quo

- The Canadian government banned several disposable plastics nationwide by the end of 2021, including shopping plastic bags, tableware, straws, and stirring rods [19].

- The European Parliament passed a directive on disposable plastics. By 2021, all European Union member states had to ban disposable plastic products, such as plastic drinking straws, plastic plates, plastic knives and forks, and styrofoam food containers and cups [20].

- The Ministry of Environment of South Korea implemented a stricter restriction on using single-use goods, including takeaway cups in coffee shops and plastic bags in supermarkets. The country aimed to reduce the use of plastic cups by 35% by the end of 2022 [21].

- Taiwan implemented comprehensive plans to tackle the problem of plastic pollution, starting in the 2000s, with measures broadly in line with recommendations from the United Nations.

2.4. Research Questions

- RQ1

- What attitudes do undergraduate students have toward DPT?

- RQ2

- What behavior do undergraduate students undertake regarding DPT?

- RQ3

- Do demographic factors affect undergraduate students’ attitudes and behavior toward DPT?

- RQ4

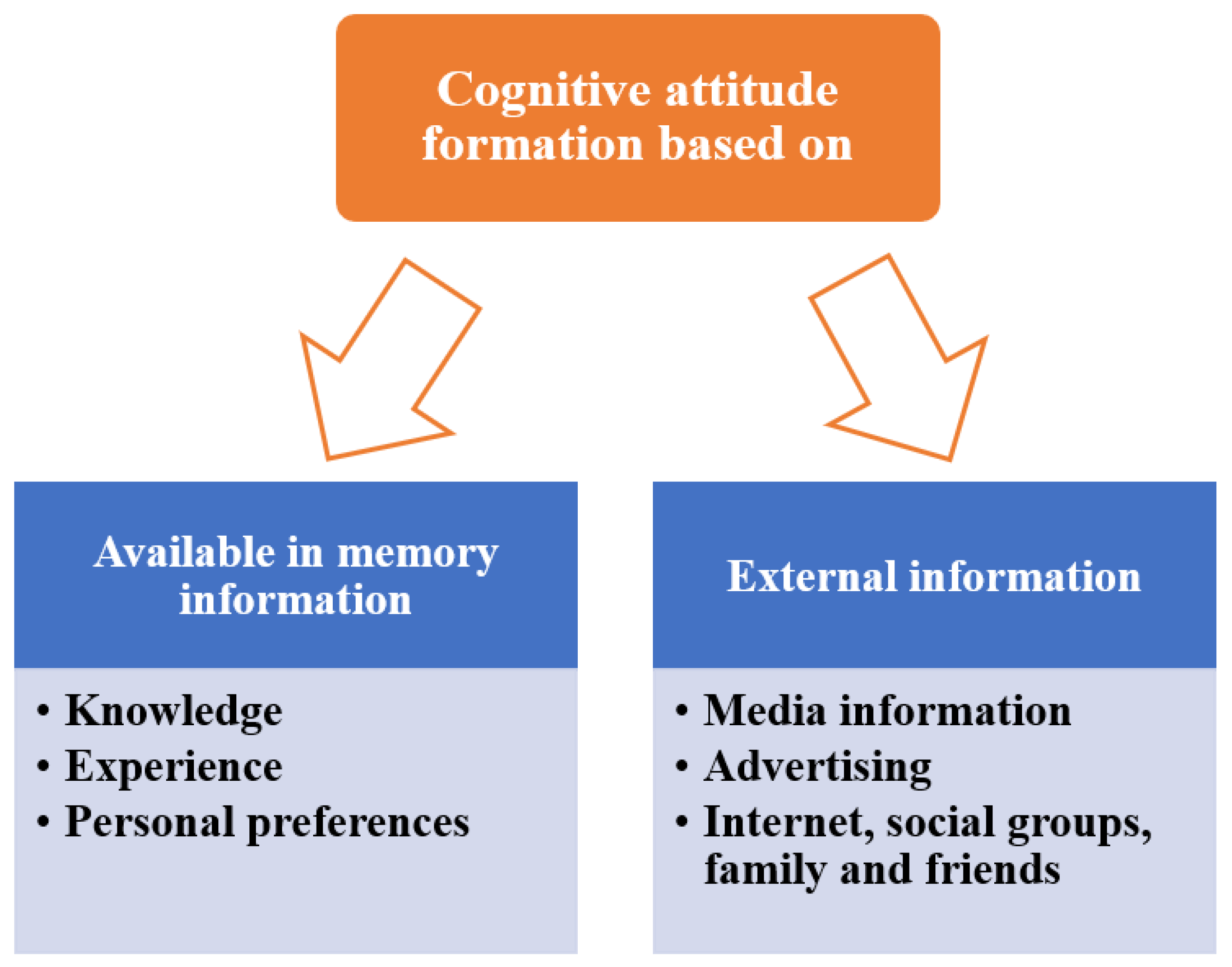

- Could cognitive attitude formation factors explain the sustainable attitudes formed by Hong Kong undergraduates at a cognitive level? Does the cognitive model in Figure 1 work for Hong Kong undergraduates?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Target Respondents and Research Design

3.2. Questionnaire Structure

- Socio-demographic questions: This section covered information related to respondents’ gender, year of study, and area of study. Year of study and area of study were also potential cognitive attitude formation factors.

- Perceptions and usage of DPT: This section contained questions about respondents’ views on the severity of environmental damage caused by DPT in Hong Kong, as well as their habits and frequency of using DPT. This section aimed to capture the cognitive aspect of their attitudes.

- Attitudes toward legislative measures: In this section, respondents were asked about their opinions on implementing legislative measures to control the use of DPT in Hong Kong. This section focused on capturing respondents’ behavioral intentions and their readiness to act on their attitudes.

- Factors influencing feelings and actions: This section explored factors that affected respondents’ emotions regarding DPT usage and their actions toward using these items. This section aimed to assess the affective component of their attitudes.

- Sustainable behavior and self-assessment: The final section focused on respondents’ sustainable behaviors related to DPT usage and included a self-assessment of their attitudes toward reducing DPT usage, integrating all three components of the ABC model.

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographics of Respondents

4.2. Findings on Undergraduates’ Attitudes and Behavior

4.3. Differences in Undergraduates’ Attitudes and Behavior by Socio-Demographic Variables

4.4. Assessing the Influence of Attitude Formation Factors on the Cognitive Component of the Attitude Formation Process Using Multiple Linear Regression

- The cognitive model in Figure 1 was proven to be valid in the online survey data of Hong Kong undergraduate students because the factors from the two types of cognitive attitude formation factors are significant. For example, the most significant factors influencing the model are I1, I3, and I4 from available in memory information and E1 and E2 from external information.

- The four significant cognitive attitude formation factors that are the drivers for positive attitudes toward reducing the use of DPT are as follows: the DPT charge (I4), action for using DPT—relevant information (E2), the problem of DPT seriously affecting your quality of life (I3), and feelings about using DPT—personal preference (E1). The higher the accepted DPT charge or the higher the rating in the other three factors, the more positive the attitude toward reducing the use of DPT.

- The DPT charge (I4) is the most impactful driver with the highest positive standardized coefficient (0.335). This result echoes the HKSAR Government’s policy to increase the plastic shopping bag charge from $0.5 to $1.0 per bag, to be effective from January 2023, as suggested by the Council for Sustainable Development (SDC) after conducting a public engagement in 2021 on the control of single-use plastics.

- Two significant cognitive attitude formation factors that are barriers to developing positive attitudes toward reducing the use of DPT are as follows: action for using DPT—media information and advertising (E2), and students in Year 3 or above (I1).

- Students in Year 3 or above have a less positive attitude toward reducing the use of DPT compared with students in Years 1 or 2. However, this inertia is not strong because its magnitude (0.118) is less than half the magnitude of the most impactful driver (0.335).

- The higher the rating in action for using DPT—media information and advertising (E2), the more negative the attitude toward reducing the use of DPT. It is the most inhibiting factor, having the highest negative standardized coefficient (−0.222), in fostering a positive attitude at the cognitive level.

5. Discussion

5.1. Attitude–Behavior Gap

5.2. Fostering Sustainable Behavior in the City

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question | Choice | Factor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | Year of study | Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 | Available in memory information |

| I2 | Area of study | Arts Business administration Education Engineering Environmental science Social science Others | Available in memory information |

| I3 | The problem of DPT seriously affects your quality of life | 5 = Strongly agree 4 = Agree 3 = Neither agree or disagree 2 = Disagree 1 = Strongly disagree | Available in memory information |

| I4 | If DPT were to be charged for in the future, what cost do you think is reasonable? | Between HK$0 and HK$5 | Available in memory information |

| E1 | To what extent do you think the following aspects# influence your feelings about the use of DPT? | 5 = Strongly agree 4 = Agree 3 = Neither agree or disagree 2 = Disagree 1 = Strongly disagree | External information |

| E2 | To what extent do you think the following aspects# influence your actions in using DPT? | 5 = Strongly agree 4 = Agree 3 = Neither agree or disagree 2 = Disagree 1 = Strongly disagree | External information |

| E3 | Did you know the Environmental Protection Department has launched a two-month public consultation? | Yes No | External information |

References

- Statistics Unit, Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department. Monitoring of Solid Waste in Hong Kong—Waste Statistics for 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.wastereduction.gov.hk/sites/default/files/msw2020.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Leslie, H.A.; van Velzen, M.J.M.; Brandsma, S.H.; Vethaak, A.D.; Garcia-Vallejo, J.J.; Lamoree, M.H. Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environ. Int. 2022, 163, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu AM, Y. Illegal waste dumping under a municipal solid waste charging scheme: Application of the neutralization theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, D.P.; Fredeen, A.L.; Booth, A.L. Reducing solid waste in higher education: The first step towards ‘greening’ a university campus. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoric, M.M.; Zhang, N.; Kasadha, J.; Tse, C.H.; Liu, J. Reducing the Use of Disposable Plastics through Public Engagement Campaigns: An Experimental Study of the Effectiveness of Message Appeals, Modalities, and Sources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakanauskas, A.P.; Kondrotienė, E.; Puksas, A. The theoretical aspects of attitude formation factors and their impact on health behaviour. Manag. Organ. Syst. Res. 2020, 83, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohner, G.; Dickel, N. Attitudes and attitude change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2011, 62, 391–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Situmorang, R.O.P.; Liang, T.C.; Chang, S.C. The difference of knowledge and behavior of college students on plastic waste problems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solinger, O.N.; van Olffen, W.; Roe, R.A. Beyond the three-component model of organizational commitment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenningsson, J.; Höst, G.; Hultén, M.; Hallström, J. Students’ attitudes toward technology: Exploring the relationship among affective, cognitive and behavioral components of the attitude construct. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2021, 32, 1531–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clore, G.L.; Schnall, S. The influence of affect on attitude. In Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracín, D., Johnson, B.T., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 437–489. Available online: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/239306/Clore%20&%20Schnall%20(2005).pdf;sequence=1 (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- An, L.; Liu, Q.; Deng, Y.; Wu, W.; Gao, Y.; Ling, W. Sources of microplastic in the environment. Microplastics Terr. Environ. Emerg. Contam. Major Chall. 2020, 95, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shershneva, E.G. Plastic waste: Global impact and ways to reduce environmental harm. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilkes-Hoffman, L.S.; Pratt, S.; Laycock, B.; Ashworth, P.; Lant, P.A. Public attitudes towards plastics. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 147, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Cai, L.; Sun, F.; Li, G.; Che, Y. Public attitudes towards microplastics: Perceptions, behaviors and policy implications. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 163, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.A. Five misperceptions surrounding the environmental impacts of single-use plastic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 14143–14151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R. Everything you Need to Know about Canada’s Single-Use Plastics Ban. Chatelaine. 2020. Available online: https://www.chatelaine.com/news/canada-single-use-plastic-ban-faq/ (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- United Nations Environment Programme. Addressing Single-Use Plastic Products Pollution: Using a Life Cycle Approach. 2021. Available online: https://www.lifecycleinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Addressing-SUP-Products-using-LCA_UNEP-2021_FINAL-Report-sml.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Ministry of Environment. Land & Waste. 2022. Available online: https://eng.me.go.kr/eng/web/index.do?menuId=466 (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Environmental Protection Department. Public Consultation Regulation of Disposable Plastic Tableware. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.hk/en/residents/government/publication/consultation/docs/2021/tableware.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Greenpeace. Microplastics and Large Plastic Debris in Hong Kong Waters 2018. 2019. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org/hongkong/issues/plastics/update/9072/ (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Cheung LT, O.; Lui, C.Y.; Fok, L. Microplastic contamination of wild and captive flathead grey mullet (Mugil cephalus). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lo, J. Measures to Curb Disposable Plastic Tableware. Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. 2021. Available online: https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/essentials-2021ise22-measures-to-curb-disposable-plastic-tableware.htm (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Chong, A.C.; Chu, A.M.; So, M.K.; Chung, R.S. Asking sensitive questions using the randomized response approach in public health research: An empirical study on the factors of illegal waste disposal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lazcano, I.; Doistua, J.; Madariaga, A. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Leisure among the Youth of Spain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogul, R. The Hong Kong Student Educating her Peers on Plastic Pollution. Young Post. 2020. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/yp/discover/lifestyle/features/article/3101596/hong-kong-student-educating-her-peers-plastic (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Clover, D.E. Environmental adult education. Adult Learn. 2002, 13, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Department. Waste Reduction Website. GREEN@COMMUNITY. 2022. Available online: https://www.wastereduction.gov.hk/en/community/crn_intro.htm (accessed on 28 April 2023).

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female Male | 188 197 | 48.8% 51.2% |

| Year of study | ||

| Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 | 53 84 113 121 14 | 13.8% 21.8% 29.4% 31.4% 3.6% |

| Area of study | ||

| Arts Business administration Education Engineering Environmental science Social science Others | 52 84 31 43 43 80 52 | 13.5% 21.8% 8.1% 11.2% 11.2% 20.8% 13.5% |

| Min | Max | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current situation of DPT is serious (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) | 2 | 5 | 4.8 | 0.44 |

| Environmental damage caused by DPT is serious (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) | 3 | 5 | 4.5 | 0.53 |

| Choice in the Question | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Extremely negative | 40 | 12.7% |

| 2 Somewhat negative | 216 | 56.1% |

| 3 Neither positive nor negative | 74 | 19.2% |

| 4 Somewhat positive | 42 | 10.9% |

| 5 Extremely positive | 4 | 1.0% |

| 385 | 100% |

| Standardized Coefficient | t-Statistic | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPT charge (I4) | 0.335 | 6.6837 | <0.001 |

| Action for using DPT—media information and advertising (E2) | −0.222 | −4.707 | <0.001 |

| Action for using DPT—relevant information (E2) | 0.159 | 3.446 | <0.001 |

| The problem of DPT seriously affects your quality of life (I3) | 0.153 | 3.224 | 0.001 |

| Undergraduate students in Year 3 or above (I1) | −0.118 | −2.669 | 0.008 |

| Feelings about using DPT—personal preference (E1) | 0.101 | 2.164 | 0.031 |

| R2 = 27.3% | |||

| The Seriousness of Environmental Damage Caused by DPT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Strong Disagree) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (Strongly Agree) | Total | ||

| The problem of DPT affects your quality of life seriously | 1 (Strongly disagree) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 40 | 25 | 68 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 54 | 91 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 18 | 32 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 11 | |

| 5 (Strongly agree) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 3 | 96 | 107 | 206 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ho, K.T.H.; Kwok, P.W.H.; Chang, S.S.Y.; Chu, A.M.Y. Gaps between Attitudes and Behavior in the Use of Disposable Plastic Tableware (DPT) and Factors Influencing Sustainable DPT Consumption: A Study of Hong Kong Undergraduates. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118958

Ho KTH, Kwok PWH, Chang SSY, Chu AMY. Gaps between Attitudes and Behavior in the Use of Disposable Plastic Tableware (DPT) and Factors Influencing Sustainable DPT Consumption: A Study of Hong Kong Undergraduates. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118958

Chicago/Turabian StyleHo, Kyle T. H., Patrick W. H. Kwok, Stephen S. Y. Chang, and Amanda M. Y. Chu. 2023. "Gaps between Attitudes and Behavior in the Use of Disposable Plastic Tableware (DPT) and Factors Influencing Sustainable DPT Consumption: A Study of Hong Kong Undergraduates" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118958