How Can Conspicuous Omni-Signaling Fulfil Social Needs and Induce Re-Consumption?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

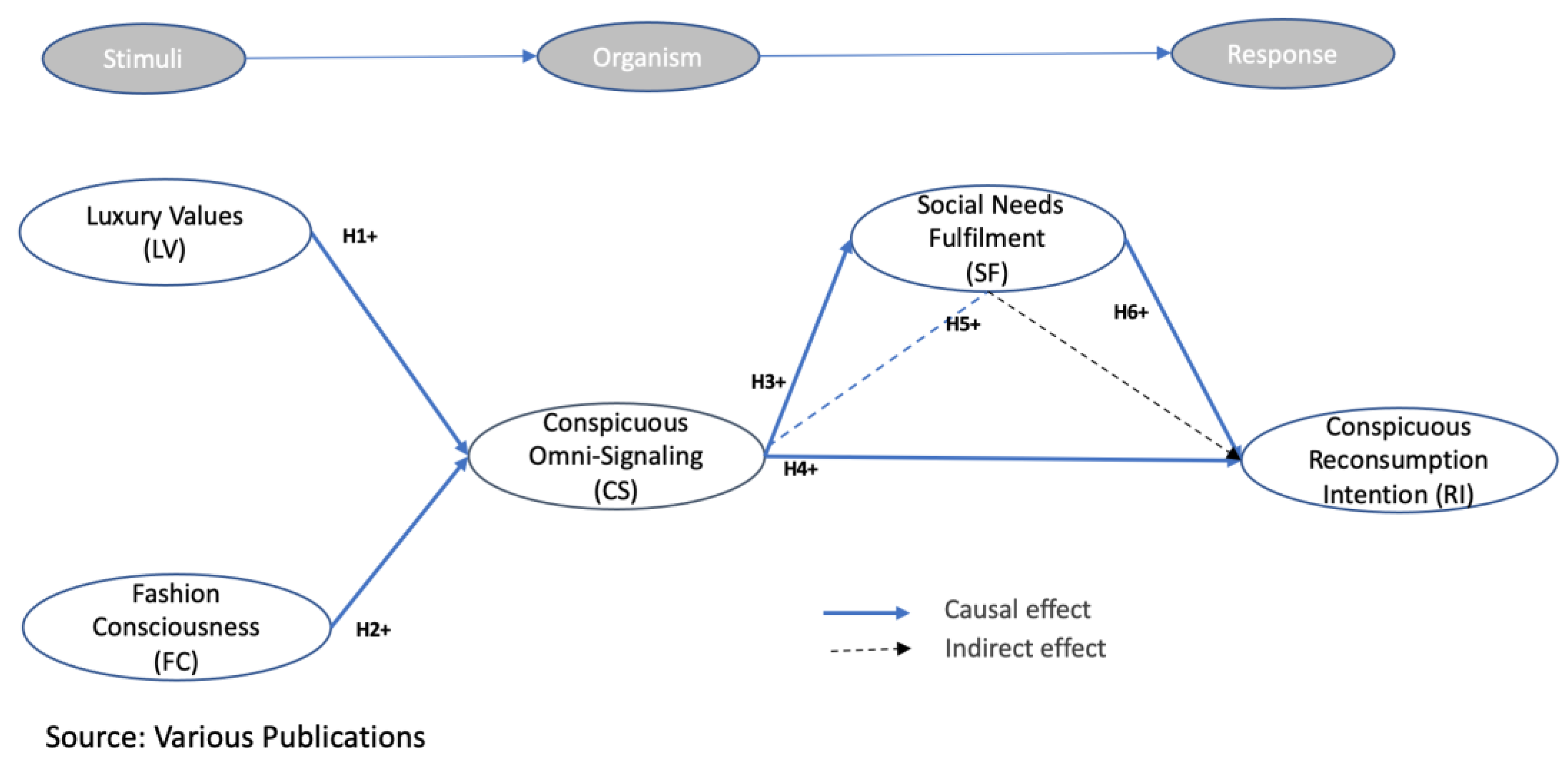

- How consumers’ psychological motives affect conspicuous omni-signaling;

- How consumers’ fashion consciousness affects conspicuous omni-signaling;

- How conspicuous omni-signaling affects social needs fulfillment which would then lead to conspicuous re-consumption;

- How conspicuous omni-signaling induces conspicuous re-consumption.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

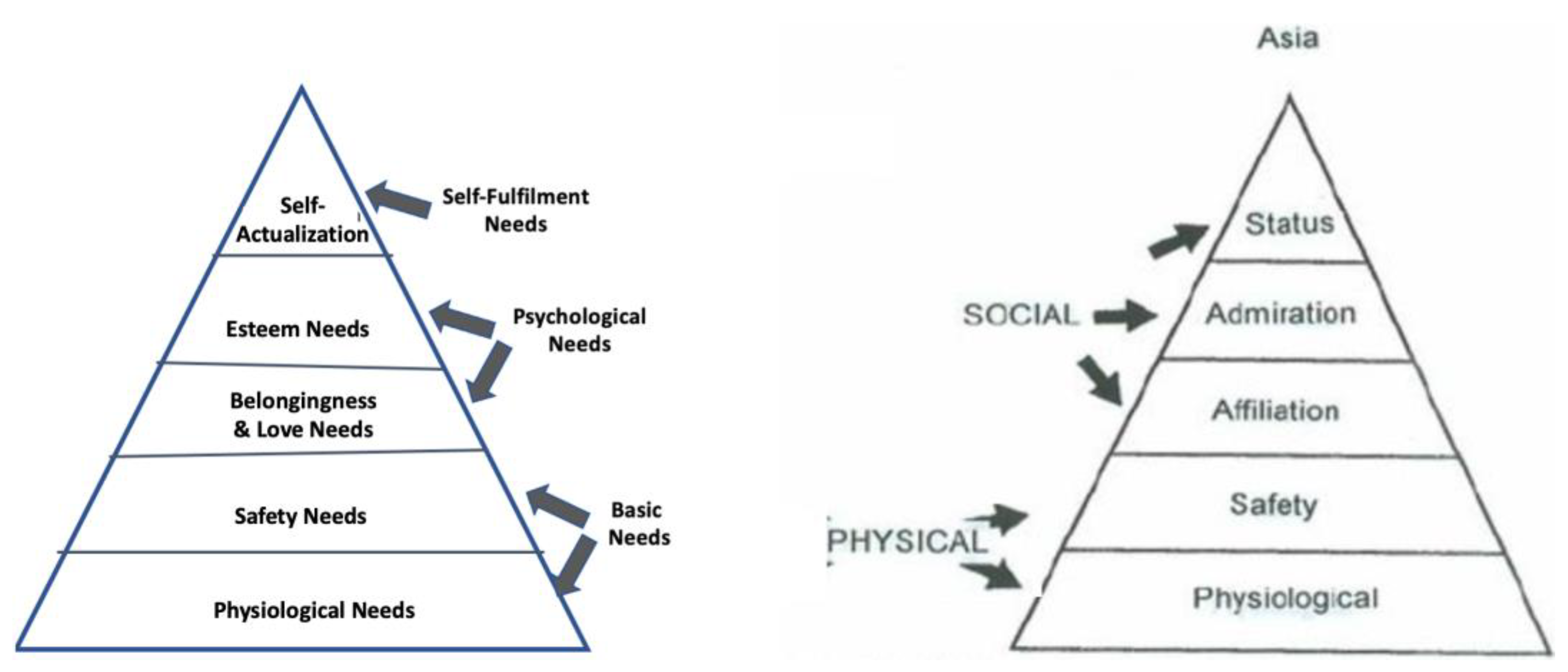

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Conspicuous Omni-Signaling

2.2.2. Luxury Values

2.2.3. Fashion Consciousness

2.2.4. Social Needs Fulfilment

2.2.5. Conspicuous Re-Consumption Intention

2.2.6. The Effect of Luxury Values on Conspicuous Omni-Signaling

2.2.7. The Effect of Fashion Consciousness on Conspicuous Omni-Signaling

2.2.8. The Effect of Conspicuous Omni-Signaling on Social Needs Fulfilment

2.2.9. The Effect of Conspicuous Omni-Signaling on Re-Consumption Intention

2.2.10. The Effect of Social Needs Fulfilment on Re-Consumption Intention

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Sample Design and Data Collection

2.3.2. Sample Characteristics

2.3.3. Measurement of Variables

2.3.4. Data Analysis

2.3.5. Descriptive Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2. Structural Model and Hypothesis Test

4. Conclusions

4.1. Discussion and Theoretical Contribution

4.2. Managerial Contribution

4.3. Limitation and Future Research Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perez-Truglia, R. A test of the conspicuous-consumption model using subjective well-being data. J. Socio Econ. 2013, 45, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, G.M.; Belk, R.W.; Wilson, J.A.J. The rise of inconspicuous consumption. J. Mark. Manag. 2015, 31, 807–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zahirovic-Herbert, V.; Chatterjee, S. What is Conspicuous Consumption? CFI—Corporate Finance Institute: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Veblen, T.B. The Theory of Leisure Class. J. Political Econ. 1899, 7, 425–455. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, G. Fashion. Am. J. Sociol. 1957, 62, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista; Hirschmann, R. Indonesia: Contribution to GDP by Industry 2019. 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1019099/indonesia-gdp-contribution-by-industry/ (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Kapferer, J.N.; Bastien, V. The specificity of luxury management: Turning marketing upside down. J. Brand Manag. 2009, 16, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilsheimer Eastman, J.; Iyer, R.; Babin, B. Luxury not for the masses: Measuring inconspicuous luxury motivations. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleres, D. Luxe-Strategies Marketing; Economica: Paris, France, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bain & Company. Global Personal Luxury Goods Market Grew 0–1% in Q1 2021: Bain. Fibre2Fashion, 18 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- BCG. Turn the Tide: Unlock the New Consumer Path to Purchase; BCG: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Fashion eCommerce Report 2021; Statista Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Broz, M. Number of Photos (2022): Statistics, Facts, & Forecasts. Available online: https://photutorial.com/photos-statistics/ (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- APJJI. “Profil Internet Indonesia 2022”, Asosiasi Penyelenggara Jasa Internet Indonesia, No. June. 2022. Available online: http://apjii.or.id/v2/upload/Laporan/Profil Internet Indonesia 2012 %28INDONESIA%29.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Digital in Indonesia: All the Statistics You Need in 2021. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-indonesia (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Sopadjieva, E.; Dholakia, U.M.; Benjamin, B. A Study of 46,000 Shoppers Shows That Omnichannel Retailing Works. Harvard Business Review, 3 January 2017; 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, D. Fulfilling social needs through luxury consumption. In Research Handbook on Luxury Branding; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, G. COVID-19′s Impact on Consumer Behavior_ What Now_—ConvertSquad, 24 June 2021. Available online: https://convertsquad.com/blog/covid-19s-impact-on-consumer-behavior-what-now/ (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Sheth, J. Impact of Covid-19 on consumer behavior: Will the old habits return or die? J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajitha, S.; Sivakumar, V.J. Understanding the effect of personal and social value on attitude and usage behavior of luxury cosmetic brands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 39, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S. Role of conspicuous value in luxury purchase intention. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2021, 39, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnasheva, R.; Suh, Y.G. The influence of social media usage, self-image congruity and self-esteem on conspicuous online consumption among millennials. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 33, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, E.; Buil, I.; Catalán, S. Facebook and luxury fashion brands: Self-congruent posts and purchase intentions. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2020, 24, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyavani, B.; Chalam, P.G. V Online Impulse Buying Behaviour—A Suggested Approach. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 20, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.C.; Wang, C.H. Clarifying the Effect of Intellectual Capital on Performance: The Mediating Role of Dynamic Capability. Br. J. Manag. 2012, 23, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.L.; Kim, K. Role of consumption values in the luxury brand experience: Moderating effects of category and the generation gap. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigg, A.B. Veblen, Bourdieu, and conspicuous consumption. J. Econ. Issues 2001, 35, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzmaurice, C.J. Conspicuous consumption and distinction, history of. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 4, ISBN 9780080970875. [Google Scholar]

- Edgell, S. Veblen and Post-Veblen Studies of Conspicuous Consumption: Social Stratification and Fashion. Int. Rev. Sociol. 1992, 3, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahavi, A.; Zahavi, A. The Handicap Principle, A Missing Piece of Darwin’s Puzzle Amotz Zahavi Avishag Zahavi. Auk 1998, 115, 544–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K. Consumption of luxury hotel experience in contemporary China: Causality model for conspicuous consumption. Tour. Rev. Int. 2018, 22, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C.; Sindermann, C.; Lester, D.; Davis, K.L. Linking individual differences in satisfaction with each of Maslow’s needs to the Big Five personality traits and Panksepp’s primary emotional systems. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütte, H.; Ciarlante, D. An Alternative Consumer Behaviour Theory for Asia. In Consumer Behaviour in Asia; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1998; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. The way to create symbolic value of luxury good—Take the Chanel No.5 perfume for a case. In Proceedings of the 2011 4th International Conference on Information Management, Innovation Management and Industrial Engineering, ICIII 2011, Shenzhen, China, 26–27 November 2011; Volume 2, pp. 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Rosendo-Rios, V.; Trott, S.; Lyu, J.; Khalifa, D. Managing the Challenge of Luxury Democratization: A Multicountry Analysis. J. Int. Mark. 2022, 30, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, F.N.; Wong, J.; Brodowsky, G. Does masstige offer the prestige of luxury without the social costs? Status and warmth perceptions from masstige and luxury signals. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, S.; Gill, T. When size does matter: Dominance versus prestige based status signaling. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, J.; Jiang, L.; Cui, A.P. A double-edged sword: How the dual characteristics of face motivate and prevent counterfeit luxury consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, N.; Bogari, N.; Salamah, N.; Zain, M. The Relationships between Collective Oriented Values and Materialism, Product Status Signaling and Product Satisfaction: A Two-City Study. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2016, 28, 807–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, E.; Buil, I.; de Chernatony, L. Consuming Good’ on Social Media: What Can Conspicuous Virtue Signalling on Facebook Tell Us About Prosocial and Unethical Intentions? J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 162, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wallace, E.; Buil, I. Seeking Likes while saving the planet: Extending the Theory of Planned Behaviour to investigate the relationship between climate-related Instagram posts and Pro-Environmental Behaviours. In Proceedings of the 50th Annual EMAC Conference, Madrid, Spain, 25–28 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.G.; Strutton, D. Does Facebook usage lead to conspicuous consumption? The role of envy, narcissism and self-promotion. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2016, 10, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Xie, Z.; Niu, J. Online low-key conspicuous behavior of fashion luxury goods: The antecedents and its impact on consumer happiness. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Vul, E. Status Signalling in the Market for Consumer Goods. psyarXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Sundie, J.M.; Cialdini, R.B.; Miller, G.F.; Kenrick, D.T. Blatant Benevolence and Conspicuous Consumption: When Romantic Motives Elicit Strategic Costly Signals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiedmann, K.P.; Hennigs, N.; Siebels, A. Value-based segmentation of luxury consumption behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 625–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, H. Personal value vs. luxury value: What are Chinese luxury consumers shopping for when buying luxury fashion goods? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.J.; Moon, H.; Kim, H.; Yoon, N. Luxury customer value. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, R.M. Fashion consciousness, materialism and fashion clothing purchase involvement of young fashion consumers in Egypt: The mediation role of materialism. J. Humanit. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2020, 4, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casidy, R.; Nuryama, A.N.; Hati, S.R.H. Linking fashion consciousness with Gen Y attitude towards prestige brands. Asia Pacfic J. Mark. Logist. 2015, 27, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nam, J.; Hamlin, R.; Gam, H.J.; Kang, J.H.; Kim, J.; Kumphai, P.; Starr, C.; Richards, L. The fashion-conscious behaviours of mature female consumers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksal, M.H. Psychological and behavioural drivers of male fashion leadership. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2014, 26, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruggencate Ten, T.; Luijkx, K.G.; Sturm, J. Social needs of older people: A systematic literature review. Ageing Soc. 2018, 38, 1745–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steverink, N.; Lindenberg, S. Which social needs are important for subjective well-being? What happens to them with aging? Psychol. Aging 2006, 21, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buijs, V.L.; Jeronimus, B.F.; Lodder, G.M.A.; Steverink, N.; de Jonge, P. Social Needs and Happiness: A Life Course Perspective. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 1953–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, M. Being and Time. Available online: https://books.google.co.id/books?hl=id&lr=&id=2P-Lc872b1UC&oi=fnd&pg=PR3&dq=being+and+time+heidegger&ots=3x5qMZXNUk&sig=3thxBtBNox6Xmdzg8Kqrj7JG6to&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=being and time heidegger&f=false (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Ki, C.; Lee, K.; Kim, Y.K. Pleasure and guilt: How do they interplay in luxury consumption? Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 722–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.A.; Levy, S.J. The temporal and focal dynamics of volitional reconsumption: A phenomenological investigation of repeated hedonic experiences. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, C.M.; Tariq, A.; Baker, T.L. From Gucci to Green Bags: Conspicuous Consumption as a Signal for Pro-Social Behavior. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2018, 26, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Manrai, A.K.; Manrai, L.A. Conspicuous consumption: A meta-analytic review of its antecedents, consequences, and moderators. J. Retail. 2021, 98, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbullah, N.N.; Sulaiman, Z.; Mas’od, A.; Ahmad Sugiran, H.S. Drivers of Sustainable Apparel Purchase Intention: An Empirical Study of Malaysian Millennial Consumers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Mitchell, V.-W.; Hennig-Thurau, T. German Consumer Decision-Making Styles. J. Consum. Aff. 2021, 35, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, J.O. The Identity of Women’s Clothing Fashion Opinion Leaders. J. Mark. Res. 1970, 7, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeola, O.; Moradeyo, A.A.; Muogboh, O.; Adisa, I. Consumer values, online purchase behaviour and the fashion industry: An emerging market context. PSU Res. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaldoss, W.; Jain, S. Pricing of conspicuous goods: A competitive analysis of social effects. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dubois, D.; Jung, S.J.; Ordabayeva, N. The psychology of luxury consumption. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 39, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, O.; Nasir, S. The effects of status consumption and conspicuous consumption on perceived symbolic status. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2022, 30, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Su, R.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y. Relation between narcissism and meaning in life: The role of conspicuous consumption. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Cass, A.; McEwen, H. Exploring consumer status and conspicuous consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2004, 4, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. Experiential aspects of consumption, holbrook.pdf. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kiranmayi, G.R. The Role of Customer’s Status Consumption and Satisfaction on Repurchase Intention. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2019, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Chen, A. Examining consumers’ luxury hotel stay repurchase intentions-incorporating a luxury hotel brand attachment variable into a luxury consumption value model. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1348–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teng, H.Y. Can film tourism experience enhance tourist behavioural intentions? The role of tourist engagement. Current Issues Tour. 2021, 24–18, 2588–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakici, A.C.; Akgunduz, Y.; Yildirim, O. The impact of perceived price justice and satisfaction on loyalty: The mediating effect of revisit intention. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Eom, T.; Chung, H.; Lee, S.; Ryu, H.B.; Kim, W. Passenger repurchase behaviours in the green cruise line context: Exploring the role of quality, image, and physical environment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahn, J.; Back, K.-J. Cruise brand experience: Functional and wellness value creation in tourism business. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2205–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Aspiring Indonesia—Expanding the Middle Class; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Matell, M.S.; Jacoby, J. Is there an optimal number of alternatives for Likert-scale items? Effects of testing time and scale properties. J. Appl. Psychol. 1972, 56, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiedmann, K.-P.; Hennigs, N.; Siebels, A. Measuring Consumers’ Luxury Value Perception: A Cross-Cultural Framework; Academy of Marketing Science Review; Academy of Marketing Science: Ruston, LA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, A.; Moital, M. Young professionals’ conspicuous consumption of clothing. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taormina, R.J.; Gao, J.H. Maslow and the motivation hierarchy: Measuring satisfaction of the needs. Am. J. Psychol. 2013, 126, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.J.; Ferrin, D.L.; Rao, H.R. A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust, perceived risk, and their antecedents. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 44, 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. WarpPLS User Manual: Version 7.0; ScriptWarp Systems: Laredo, TX, USA, 2021; pp. 1–122. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Brunsveld, N. Essentials of Business Research Methods; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2019; ISBN 9780429511950. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, S.; Paul, J. Intrinsic motivation of luxury consumers in an emerging market. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebarajakirthy, C.; Das, M. Uniqueness and luxury: A moderated mediation approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sproles, G.B. Fashion Theory: A Conceptual Framework. Adv. Consum. Res. 1974, 1, 463–472. [Google Scholar]

| Studies | Online/ Offline | Independent Variable | Mediating Variable | Dependent Variable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [35] | Offline | Conspicuous Signaling | Positive Affect | Luxury Purchase Intention |

| [36] | Offline | Luxury Signaling | Impression Management. Envy | Status |

| [37] | Offline | Status Signaling | Hubristic Pride | Product Preference |

| [38] | Offline | Brand social Power | Signaling Effectiveness | Luxury brand purchase intention |

| [39] | Offline | Materialism (luxury values) | Status Signaling | Product Satisfaction |

| [40] | Online | NFU, ATSC (luxury values) | Conspicuous Virtue Signaling | Purchase Intention |

| [41] | Online | Like Seeking Behaviors. Subjective norms | Conspicuous Virtue Signaling | Pro-environmental behaviors |

| [42] | Online | Envy, Narcissism (luxury values) | Desire for Self-promotion | Conspicuous Online Consumption |

| [43] | Online | Self-presentation, Avoidance of negative comments | Online LK Conspicuous Behaviors | Image, interpersonal relationship, Happiness |

| This Study | Omni (Offline + Online) | Fashion Consciousness, Luxury Values | Conspicuous Omni-signaling, Social Needs Fulfilment | Conspicuous Re-consumption Intention |

| Subgroup | Freq | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender Female | 362 | 76 |

| Male | 112 | 24 |

| Age 25–29 years | 47 | 10 |

| 30–39 | 99 | 21 |

| 40–49 | 146 | 31 |

| ≥50 | 182 | 38 |

| Disp. Income 700–1750 | 315 | 67 |

| (~USD) 1751–3500 | 115 | 24 |

| >3500 | 44 | 9 |

| Purchase Freq. 1–2x | 310 | 65 |

| 3–5x >5s | 110 54 | 23 11 |

| Purchase Value <70 | 9 | 2 |

| (~USD) 71–175 | 106 | 22 |

| 176–350 | 130 | 27 |

| 351–700 | 112 | 24 |

| >700 | 117 | 25 |

| Variable | Dimension | Code | Item | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luxury Values (LV) | LV1 | Luxury fashion offers excellent quality and aesthetics | [24,46] | |

| LV2 | Luxury fashion as self-gift to reward myself for important events or achievements. | |||

| LV3 | Luxury fashion helps me to express myself | |||

| LV4 | Luxury fashion is considered as symbol of prestige | |||

| LV5 | Luxury fashion is considered as reflective of social status | |||

| Fashion Consciousness (FC) | FC1 | I usually have one or more outfits that are of the very latest style | [51] | |

| FC2 | When I must choose between the two, i.e., dress for fashion or dress for comfort—I usually choose dress for fashion, not dress for comfort | |||

| FC3 | An important part of my life and activities is dressing smartly | |||

| FC4 | It is important to me that my clothes be of the latest style | |||

| Conspicuous Omni-signaling (CS) | Offline | CS1 | Wearing luxury fashion increased my status and prestige | [20,81] |

| CS2 | Attending party with luxury fashion increased my status and prestige | |||

| CS3 | Attending social/community gathering with luxury fashion increased my status and prestige | |||

| Online | CS4 | Posting luxury fashion on social media increased my self-esteem | ||

| CS5 | Pressing “like” and writing “comment” about luxury fashion in social media increased my self-esteem | |||

| CS6 | I follow social media account of fashion influencer to increase my self-esteem | |||

| Social Needs Fulfilment (SF) | SF1 | I am completely satisfied with how much I am welcomed in my community | [84] | |

| SF2 | I am completely satisfied with the feeling of togetherness I have with my friends | |||

| SF3 | I am completely satisfied with the prestige I have in the eyes of other people | |||

| SF4 | I am completely satisfied with the social status I have in the eyes of other people | |||

| SF5 | I am completely satisfied with the high esteem that other people have for me | |||

| Conspicuous Re-consumption Intention (RI) | RI1 | I am likely to repurchase the same brand(s) of luxury fashion in the next one year | [85,26] | |

| RI2 | I will purchase additional items from the same brand(s) of luxury fashion in the next 1 year | |||

| RI3 | I will continue to use this brand | |||

| RI4 | I will convey positive opinions about experiences with this brand | |||

| RI5 | I am willing to recommend this brand to others |

| Variable | N | Mean | Min | Max | SE | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV | 474 | 3.95 | 1.4 | 5.0 | 0.03 | 0.60 | −0.61 | 1.40 |

| FC | 474 | 3.16 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 0.04 | 0.80 | −0.55 | −0.16 |

| CS | 474 | 3.21 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 0.04 | 0.88 | −0.45 | −0.23 |

| SF | 474 | 3.65 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 0.04 | 0.79 | −1.26 | 1.90 |

| RI | 474 | 3.81 | 1.6 | 5.0 | 0.02 | 0.54 | −0.67 | 1.85 |

| Variable | Dimension | Item | LV | FC | CS | SF | RI | p Value | Convergence | Discriminant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luxury Values (LV) | LV1 | 0.576 | 0.112 | −0.399 | 0.041 | 0.084 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | |

| LV2 | 0.552 | 0.241 | −0.614 | −0.13 | 0.032 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| LV3 | 0.776 | 0.158 | −0.107 | −0.008 | 0.011 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| LV4 | 0.842 | −0.242 | 0.441 | 0.021 | −0.001 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| LV5 | 0.841 | −0.139 | 0.334 | 0.043 | −0.087 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| Fashion Consciousness (FC) | FC1 | 0.099 | 0.743 | −0.163 | −0.113 | 0.245 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | |

| FC2 | −0.202 | 0.801 | 0.234 | −0.047 | −0.095 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| FC3 | 0.134 | 0.754 | −0.144 | 0.141 | −0.109 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| FC4 | −0.014 | 0.877 | 0.048 | 0.017 | −0.027 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| Conspicuous Omni-signaling (CS) | Offline | CS1 | 0.017 | 0.034 | 0.936 | −0.015 | −0.024 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid |

| CS2 | −0.045 | 0.006 | 0.947 | 0.033 | −0.005 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| CS3 | 0.028 | −0.040 | 0.948 | −0.018 | 0.029 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| Online | CS4 | 0.027 | −0.179 | 0.893 | 0.045 | −0.032 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | |

| CS5 | −0.065 | 0.027 | 0.936 | −0.033 | −0.006 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| CS6 | 0.040 | 0.149 | 0.901 | −0.010 | 0.038 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| Social Needs Fulfilment (SF) | SF1 | 0.051 | 0.059 | −0.231 | 0.857 | 0.082 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | |

| SF2 | −0.1 | 0.058 | −0.216 | 0.832 | 0.003 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| SF3 | 0.044 | −0.122 | 0.277 | 0.843 | 0.005 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| SF4 | 0.06 | −0.076 | 0.173 | 0.896 | −0.049 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| SF5 | −0.06 | 0.085 | −0.012 | 0.859 | −0.039 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| Re-consumption Intention (RI) | RI1 | 0.128 | −0.04 | −0.166 | −0.118 | 0.771 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | |

| RI2 | 0.24 | 0.135 | −0.422 | −0.098 | 0.745 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| RI3 | 0.084 | −0.025 | −0.136 | 0.011 | 0.703 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| RI4 | −0.268 | −0.058 | 0.475 | 0.1 | 0.644 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid | ||

| RI5 | −0.248 | −0.022 | 0.351 | 0.14 | 0.659 | <0.001 | Valid | Valid |

| Variable | Dimension | AVE (≥0.50) | Validity | C. Alpha (≥0.70) | CR (≥0.70) | Reliability | VIF (≤5) | Multicollinearity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV | 0.53 | Valid | 0.77 | 0.85 | Reliable | 1.80 | No | |

| FC | 0.63 | Valid | 0.81 | 0.87 | Reliable | 2.23 | No | |

| CS | 0.83 | Valid | 0.8 | 0.91 | Reliable | 2.95 | No | |

| Offline | 0.89 | Valid | 0.94 | 0.96 | Reliable | 2.76 | No | |

| Online | 0.83 | Valid | 0.90 | 0.94 | Reliable | 2.64 | No | |

| SF | 0.74 | Valid | 0.91 | 0.93 | Reliable | 1.63 | No | |

| RI | 0.50 | Valid | 0.75 | 0.83 | Reliable | 1.41 | No |

| Fornell-Larcker Criterion | HTMT Ratio | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV | FC | CS | SF | RI | LV | FC | CS | FS | RI | ||

| LV | 0.73 | LV | |||||||||

| FC | 0.47 | 0.80 | FC | 0.59 | |||||||

| CS | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.91 | CS | 0.81 | 0.88 | |||||

| SF | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.86 | FS | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.68 | |||

| RI | 0.37 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.71 | RI | 0.48 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.49 | |

| Endogen Variable | R2 (≥0.2) | Adj. R2 (≥0.2) | Q2 (>0) | Good Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 0.638 | 0.636 | 0.638 | Strong |

| SF | 0.341 | 0.340 | 0.342 | Moderate |

| RI | 0.258 | 0.255 | 0.257 | Moderate |

| Indices | Score | Acceptable | Value | Notes |

| Average path coefficient (APC) | 0.415 | p < 0.05 | p < 0.001 | Good Fit |

| Average R squared (ARS) | 0.412 | p < 0.05 | p < 0.001 | Good Fit |

| Average adjusted R squared (AARS) | 0.410 | p < 0.05 | p < 0.01 | Good Fit |

| Average block FIV (AVIF) | ideal ≤ 3.3 | 1.45 | Good Fit | |

| Average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF) | ideal ≤ 3.4 | 2.00 | Good Fit | |

| Tenenhaus GoF (GoF) | ideal ≥ 0.36 | 0.52 | Good Fit | |

| Sympson’s paradox ratio (SPR) | Acceptable 0.7– 1.0 | 1.00 | Good Fit | |

| R-squared contribution ratio (RSCR)\ | Acceptable 0.9–1 | 1.00 | Good Fit | |

| Statistical suppression ratio (SSR) | Acceptable ≥ 0.70 | 1.00 | Good Fit | |

| Non-linear bivariate causality direction ratio (NLBCDR) | Acceptable ≥ 0.70 | 1.00 | Good Fit | |

| Standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) | Acceptable ≤ 0.1 | 0.10 | Good Fit | |

| Standardized mean absolute residual (SMAR) | Acceptable ≤ 0.1 | 0.08 | Good Fit | |

| Standardized threshold difference count ration (STDCR) | Acceptable ≥ 0.7; Ideal = 1 | 0.94 | Good Fit | |

| H | Path | β | p Value (≤0.05) | Standard Error (≥0.02) | T-Ratio (≥1.96) | f2 (≥0.02) | Supported | Past Studies (Effect) | This Study (Effect) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | LV→CS | 0.414 | <0.001 *** | 0.044 | 9.489 | 0.272 | Yes | Positive | Positive |

| H2 | FC→CS | 0.515 | <0.001 *** | 0.043 | 11.946 | 0.366 | Yes | Positive | Positive |

| H3 | CS→SF | 0.584 | <0.001 *** | 0.043 | 13.679 | 0.341 | Yes | Conflicting: positive, negative | Positive |

| H4 | CS→RI | 0.340 | <0.001 *** | 0.044 | 7.718 | 0.161 | Yes | Positive | Positive (direct) |

| H5 | CS→SF→RI | 0.131 | <0.001 *** | 0.032 | 4.094 | 0.062 | Yes | Positive | Positive (indirect) |

| H6 | SF→RI | 0.225 | <0.001 *** | 0.045 | 5.039 | 0.096 | Yes | Positive | Positive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hamdani, A.; So, I.G.; Maulana, A.E.; Furinto, A. How Can Conspicuous Omni-Signaling Fulfil Social Needs and Induce Re-Consumption? Sustainability 2023, 15, 9015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15119015

Hamdani A, So IG, Maulana AE, Furinto A. How Can Conspicuous Omni-Signaling Fulfil Social Needs and Induce Re-Consumption? Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):9015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15119015

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamdani, Ahmad, Idris Gautama So, Amalia E. Maulana, and Asnan Furinto. 2023. "How Can Conspicuous Omni-Signaling Fulfil Social Needs and Induce Re-Consumption?" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 9015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15119015