Why Do Consumers Buy Green Smart Buildings without Engaging in Energy-Saving Behaviors in the Workplace? The Perspective of Materialistic Value

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Materialism

2.2. Energy-Saving Behaviors

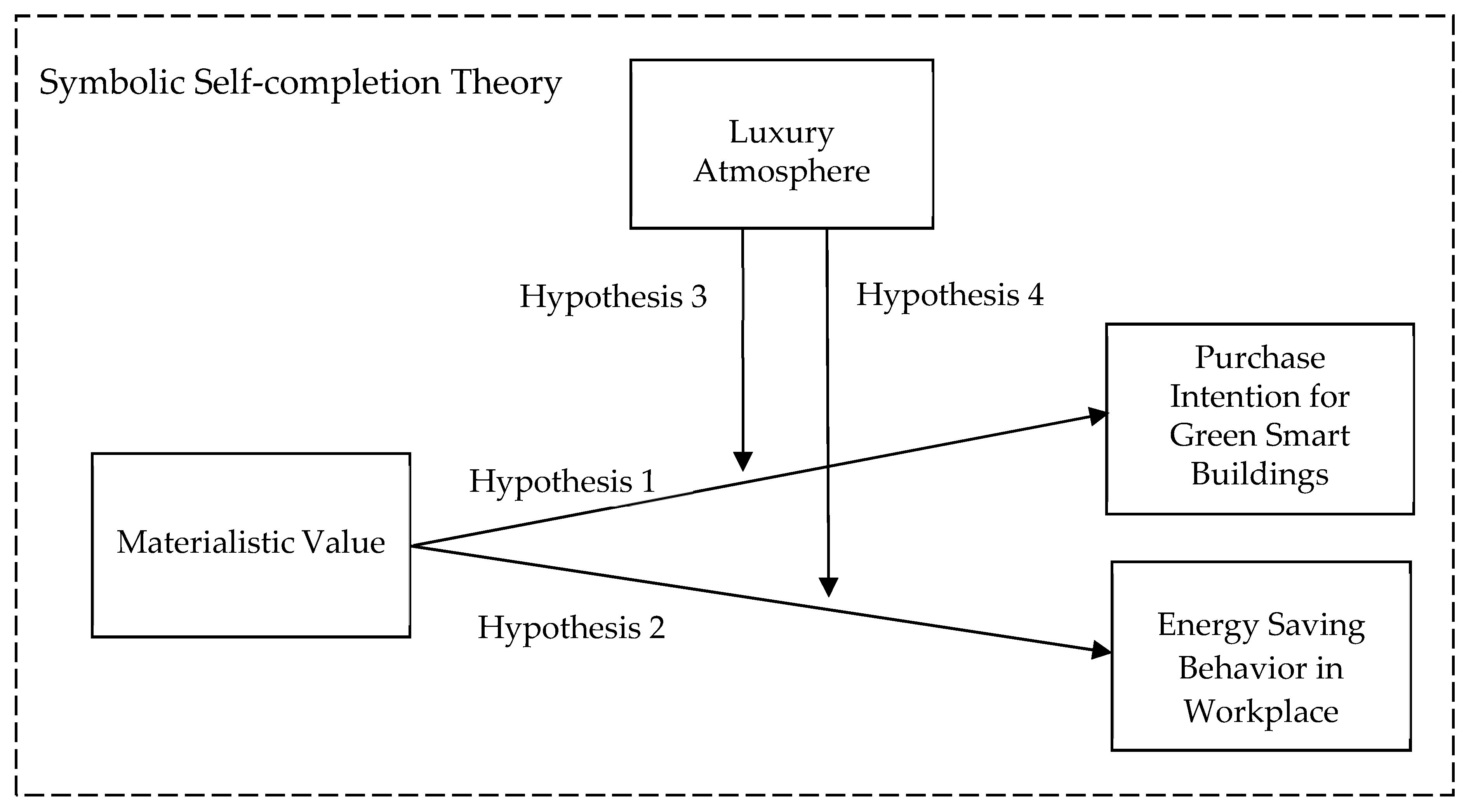

2.3. Materialistic Value, Purchase Intention for Green Smart Buildings, and Energy-Saving Behavior in the Workplace

2.4. Moderating Effect of Luxury Atmosphere

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurements

3.2. Sample Collection

4. Analysis Results

4.1. Validity and Reliability

4.2. Analysis Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Contributions

5.3. Future Research and Limitations

5.4. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lyu, C.; Hu, J.; Zhang, R.; Chen, W.; Xu, P. Optimizing the evaluation model of green building management based on the concept of urban ecology and environment. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 10, 1094535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmjoo, A.; Nezhad, M.M.; Kaigutha, L.G.; Marzband, M.; Mirjalili, S.; Pazhoohesh, M.; Memon, S.; Ehyaei, M.A.; Piras, G. Investigating Smart City Development Based on Green Buildings, Electrical Vehicles and Feasible Indicators. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, Y.-J.; Shao, Y.-F.; Cao, Q. The Impact of Sustainable Transformational Leadership on Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity: Empirical Evidence From Green Building Industries of China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 814690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.; Owusu-Manu, D.-G. Ameyaw EE. Drivers for implementing green building technologies: An international survey of experts. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 145, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palm, M.; Raynor, K.E.; Warren-Myers, G. Examining building age, rental housing and price filtering for affordability in Melbourne, Australia. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 809–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwan Architecture Center. Taiwan Green Smart Building Statistics; Taiwan Architecture Center: New Taipei City, Taiwan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Eagleton, T. Materialism; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pandelaere, M. Pursuing affiliation through consumption. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 46, 101330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, M.; Dittmar, H.; Bond, R.; Kasser, T. The relationship between materialistic values and environmental attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Gao, S.; Wang, R.; Jiang, J.; Xu, Y. The Negative Associations Between Materialism and Pro-Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors: Individual and Regional Evidence From China. Environ. Behav. 2020, 52, 611–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizhakova, Y.; Coulter, R.A. The ‘green’ side of materialism in emerging BRIC and developed markets: The moderating role of global cultural identity. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2013, 30, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Liobikas, J.; Brizga, J.; Juknys, R. Materialistic values impact on pro-environmental behavior: The case of transition country as Lithuania. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepf, C.; Overhoff, L.; Koth, S.C.; Gabriel, M.; Briels, D.; Auer, T. Impact of a Weather Predictive Control Strategy for Inert Building Technology on Thermal Comfort and Energy Demand. Buildings 2023, 13, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Maher, M.L. Conceptual Metaphors for Designing Smart Environments: Device, Robot, and Friend. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez, I.; Zalba, B.; Trillo-Lado, R.; Blanco, T.; Cambra, D.; Casas, R. Internet of Things (IoT) as Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Enabling Technology towards Smart Readiness Indicators (SRI) for University Buildings. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicklund, R.A.; Gollwitzer, P.M. Symbolic Self-Completion; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wicklund, R.A.; Gollwitzer, P.M. Symbolic self-completion, attempted influence, and self-deprecation. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 2, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L. When Wanting is Better than Having: Materialism, Transformation Expectations, and Product-Evoked Emotions in the Purchase Process. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 40, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.J. The relationship of materialism to spending tendencies, saving, and debt. J. Econ. Psychol. 2003, 24, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unanue, W.; Vignoles, V.L.; Dittmar, H.; Vansteenkiste, M. Life goals predict environmental behavior: Cross-cultural and longitudinal evidence. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 46, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, D.; Nässén, J. Should environmentalists be concerned about materialism? An analysis of attitudes, behaviours and greenhouse gas emissions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; Tjiptono, F. The End of Religion? Examining the Role of Religiousness, Materialism, and Long-Term Orientation on Consumer Ethics in Indonesia. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 123, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, Q.; Nieuwenhijsen, I.; Vries de Blokhuis, E.; Schaefer, W. Intervention strategy to stimulate energy-saving behavior of local residents. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sütterlin, B.; Brunner, T.A.; Siegrist, M. Who puts the most energy into energy conservation? A segmentation of energy consumers based on energy-related behavioral characteristics. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 8137–8152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyberg, P.; Palm, J. Influencing households’ energy behaviour—How is this done and on what premises? Energy Policy 2009, 37, 2807–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, D. Who exhibits more energy-saving behavior in direct and indirect ways in china? The role of psychological factors and socio-demographics. Energy Policy 2016, 93, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; She, Y.; Wang, S.; Dora, M. Impact of Psychological Factors on Energy-Saving Behavior: Moderating Role of Government Subsidy Policy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L. The Material Values Scale: Measurement Properties and Development of a Short Form. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fitzmaurice, J. Splurge purchases and materialism. J. Consum. Mark. 2008, 25, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastovicka, J.L.; Bettencourt, L.A.; Hughner, R.S.; Kuntze, R.J. Lifestyle of the Tight and Frugal: Theory and Measurement. J. Consum. Res. 1999, 26, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.; Cai, T.; Deng, T.; Li, X. Factors affecting non-green consumer behaviour: An exploratory study among Chinese consumers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- John, D.R. Consumer Socialization of Children: A Retrospective Look at Twenty-Five Years of Research. J. Consum. Res. 1999, 26, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, J.E.; Rindfleisch, A. Materialism and Well-Being: A Conflicting Values Perspective. J. Consum. Res. 2002, 29, 348–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Acevedo-Duque, Á. PERVAINCONSA Scale to Measure the Consumer Behavior of Online Stores of MSMEs Engaged in the Sale of Clothing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.V.; Chen, Y.-C. Assessment of Enhancing Employee Engagement in Energy-Saving Behavior at Workplace: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. Generalized expectancies of interpersonal trust. Am. Psychol. 1971, 26, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Y. How can corporate social responsibility predict voluntary pro-environmental behaviors? Energy Environ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Y.B.; Lee, C.-J. Predicting continuance intention to fintech chatbot. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 129, 107027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Y.B.; Li, M.-W.; Lee, Y.-S. Why Do Medium-Sized Technology Farms Adopt Environmental Innovation? The Mediating Role of Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.R.; Larcker, F.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, B.J.; Phillips, L.W.; Tybout, A.M. Designing Research for Application. J. Consum. Res. 1981, 8, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, H.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J. What Makes Employees Green Advocates? Exploring the Effects of Green Human Resource Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Ge, J.; Xu, Q.; Yang, T. Terminal Distributed Cooperative Guidance Law for Multiple UAVs Based on Consistency Theory. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, Z.; Ye, L.; Guo, M.; Liu, S. Future Work Self and Employee Creativity: The Mediating Role of Informal Field-Based Learning for High Innovation Performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Items | λ | Cronbach’s α | Composite Reliability | Average Variation Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Materialistic Value | MV01 | 0.861 ** | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.64 |

| MV02 | 0.882 ** | ||||

| MV03 | 0.845 ** | ||||

| MV04 | 0.721 ** | ||||

| MV05 | 0.779 ** | ||||

| MV06 | 0.812 ** | ||||

| MV07 | 0.832 ** | ||||

| MV08 | 0.756 ** | ||||

| MV09 | 0.724 ** | ||||

| MV10 | 0.861 ** | ||||

| Purchase Intention for Green Smart Buildings | PIB01 | 0.893 ** | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.63 |

| PIB02 | 0.906 ** | ||||

| PIB03 | 0.793 ** | ||||

| PIB04 | 0.716 ** | ||||

| Energy-Saving Behavior at Workplace | EW01 | 0.836 ** | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.79 |

| EW02 | 0.875 ** | ||||

| EW03 | 0.830 ** | ||||

| Luxury Atmosphere | LA01 | 0.764 ** | 0.91 | 0.92 | |

| LA02 | 0.734 ** | ||||

| LA03 | 0.752 ** | ||||

| LA04 | 0.710 ** |

| Hypothesis | Relationship Path | Coefficient | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Materialistic Value -> Purchase Intention for Green Smart Building | 0.52 ** | H1 is supported |

| H2 | Materialistic Value -> Energy-Saving Behavior in the Workplace | −0.31 ** | H2 is supported |

| H3 | Materialistic Value*Luxury Atmosphere -> Purchase Intention for Green Smart Building | 0.09 ** | H3 is supported |

| H4 | Materialistic Value*Luxury Atmosphere -> Energy-Saving Behavior in the Workplace | −0.05 ** | H4 is supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chu, L. Why Do Consumers Buy Green Smart Buildings without Engaging in Energy-Saving Behaviors in the Workplace? The Perspective of Materialistic Value. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129278

Chu L. Why Do Consumers Buy Green Smart Buildings without Engaging in Energy-Saving Behaviors in the Workplace? The Perspective of Materialistic Value. Sustainability. 2023; 15(12):9278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129278

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Lydia. 2023. "Why Do Consumers Buy Green Smart Buildings without Engaging in Energy-Saving Behaviors in the Workplace? The Perspective of Materialistic Value" Sustainability 15, no. 12: 9278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129278