Green Dental Environmentalism among Students and Dentists in Greece

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Pro-Environmetal Behaviors

2.2. Theories of Pro-Environmental Behavior

3. Research Methods

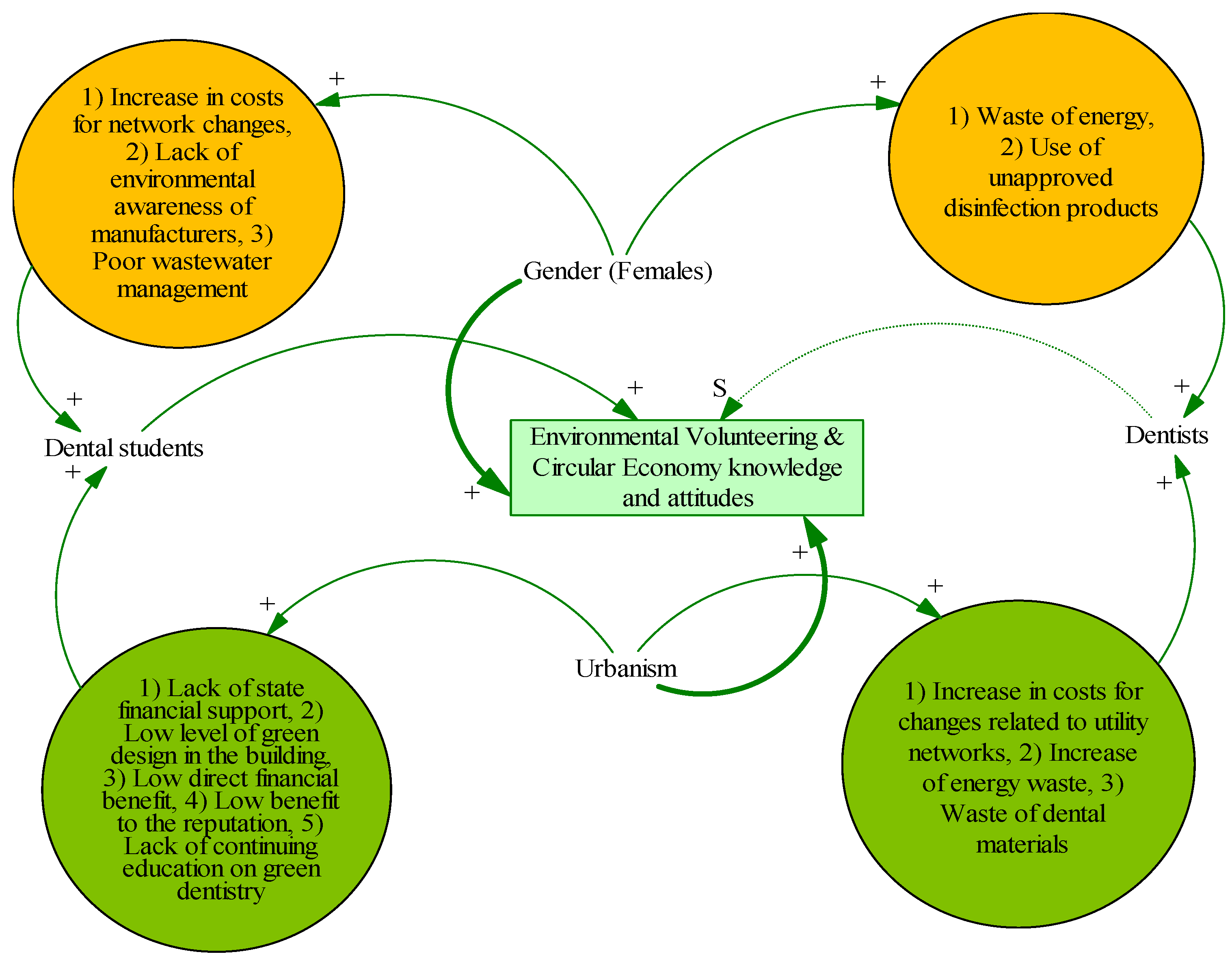

3.1. Identification of Factors Influencing Sustainable Design and Planning

3.2. Methodology of Designing the Study Questionnaire

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

Appendix A. Questionnaire for Dental Students

- Part A. Demographics:

- Q1. What is your gender? male_female_other

- Q2. Which is your semester of studies? 4o_6o_8o_10o semester (undergraduate level)

- Q3. Where does your family live? capital_other urban city_mainland/non urban areas_islands/non urban areas

- Q4. What is the highest educational level of your family members? (refer to the parent who has the highest level of education); elementary_gymnasium/lyceum_college_university

- Part B. Environmental bevahiors regarding volunteering and knowledge of legislation

- Q5. Do you use recycling at home? Yes_ No_I prefer not to answer

- Q6. Have you ever participated in voluntary environmental activities at your place of residence or during your studies? Yes_ No_I prefer not to answer

- Q7. Are you aware of the principles of the circular economy in the dental practice? Yes_ No_I prefer not to answer

- Q8. Are you aware of the current European Union legislation about mercury use and disposal?

- Yes_ No_I prefer not to answer

- Q9. Are you aware of the current European Union legislation about plastic recycling? Yes_ No_I prefer not to answer

- Part C. Importance of factors influencing environmental attitudes

- Q10. Evaluate the following factors depending on the importance you think they have for a green dental practice (note the one that most accurately represents your view) 1: extremely insignificant, 2: relatively insignificant, 3: neutral, 4: significant, 5: extremely significant

- Q10.1 Lack of regulations and national legislation

- Q10.2 Lack of state control

- Q10.3 Lack of specific technical knowledge and support during the construction of the building

- Q10.4 Lack of specific technical knowledge and support during the design of the dental practice

- Q10.5 Lack of financial support to design a green dental practice

- Q10.6 Low level of “green design” in buildings

- Q10.7 Lengthening the construction time of a green dental practice

- Q10.8 Increase in costs for related changes to utility networks

- Q10.9 Increase in the necessary and mandatory space for a dental practice

- Q10.10 Higher cost of buying/renting a green dental practice

- Q10.11 Possible damage to the structure of the buildings if green changes are performed after construction

- Q10.12 Lack of developed knowledge about green building construction

- Q10.13 Immature market of green construction materials for health offices

- Q10.14 The economic benefit of a green dental practice is not visible in the near future

- Q10.15 Questions and doubts from patients about the safety of green construction materials

- Q10.16 Low demand for green buildings

- Q10.17 Lack of environmental awareness of manufacturers

- Q10.18 Lack of environmental awareness of the public

- Q10.19 Lack of advertising for green dental practice

- Q10.20 Lack of training on green dentistry issues

- Q10.21 Waste of water in the dental practice

- Q10.22 Poor wastewater management in the dental practice

- Q10.23 Incomplete management of household waste

- Q10.24 Cost of septic waste collection

- Q10.25 Cost of air purification devices in the dental practice

- Q10.26 Reduced application of renewable energy sources in public

- Q10.27 Reduced application of renewable energy sources in the dental practice

- Q10.28 Negligible reputational benefits for green dental practices by today’s standards

- Q10.29 Lack of general instruction from regional dental associations about paper and plastic recycling in the dental practice

- Q10.30 Lack of training seminars on environmentally friendly dentistry

- Part D. Estimation of educational needs and participants’ proposals

- Q11. Needs for seminars about environmental sustainability in dental practices (please complete)…

- Q12. Proposals and suggestions for the environmentally friendly dental practices of the future (please complete)…

Appendix B. Questionnaire for Dentists

- Part A. Demographics:

- Q1. What is your gender? male_female_other

- Q2. For how many years have you worked as a dentist? 0-5_6-10_11-20_21-30_31 and over

- Q3. Where do you work as a dentist? capital_other urban city_mainland/non urban areas_islands/non urban areas

- Q4. How do you perform dentistry? private practice_employee_academic_public sector_other

- Q5. Which is your main field of practicing dentistry? general dentistry_endodontics_periodontics_prosthetics, orthodontics_paedodontics_restorative/esthetic dentistry_oral surgery_other

- Q6. Have you ever participated in voluntary environmental actions at your place of residence or work? Yes_ No_I prefer not to answer

- Q7. How many employees do you have in your practice? None_1-2_3-4_5 and more

- Part B. Pro-environmental bevahiors regarding volunteering and knowledge of legislation

- Q8. Do you use recycling at home? Yes_ No_I prefer not to answer

- Q9. Do you use recycling at work? Yes_ No_I prefer not to answer

- Q10. Are you aware of the principles of the circular economy in dental practice? Yes_ No_I prefer not to answer

- Q11. Are you aware of the current European Union legislation about mercury use and disposal?Yes_ No_I prefer not to answer

- Q12. Are you aware of the current European Union legislation about plastic recycling? Yes_ No_I prefer not to answer

- Q13. What is the most negative environmental behavior in the dental practice?

- Q13.1 The collection of septic along with household waste

- Q13.2 The non-application of documented antisepsis protocols

- Q13.3 Noise production

- Q13.4 Waste of energy

- Q13.5 Waste of water

- Q13.6 Waste of dental materials

- Q13.7 The use of non-recyclable single-use products

- Q13.8 The use of uncertified disinfection products

- Part C. Estimation of the importance of factors influencing pro-environmental attitudes

- Q14. (as Q10 in Appendix A)

- Part D. Estimation of educational needs and participants’ proposals

- Q15. (as Q11 in Appendix A)

- Q16. (as Q12 in Appendix A)

References

- WHO. Green and New Evidence and Perspectives for Action Blue Spaces and Mental Health. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/342931/9789289055666-eng.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Cvenkel, N. Well-Being in the Workplace: Governance and Sustainability Insights to Promote Workplace Health; On Approaches to Global Sustainability Markets and Governance; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsopoulos, D. Organizational Energy Conservation Matters in the Anthropocene. Energies 2022, 15, 8214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.G.; MacNaughton, P.; Laurent, J.G.C. Green Buildings and Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scrima, F.; Mura, A.L.; Nonnis, M.; Fornara, F. The relation between workplace attachment style, design satisfaction, privacy and exhaustion in office employees: A moderated mediation model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 78, 101693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M. Quality of Life and Satisfaction from Career and Work–Life Integration of Greek Dentists before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EC. A Resource-Efficient Europe—Flagship Initiative under the Europe 2020 Strategy; COM 21; European Commision: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- EC. Road Map to a More Resource Efficient Europe; SEC 1067; European Commision: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- EC. New Circular Economy Action Plan. 2020. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/circular-economy-action-plan_en (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- FDI Consensus Statement. Consensus on Environmentally Sustainable Oral Healthcare: A Joint Stakeholder Statement. Available online: https://www.fdiworlddental.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/Consensus%20Statement%20-%20FDI.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Antoniadou, M.; Varzakas, T.; Tzoutzas, I. Circular Economy in Conjunction with Treatment Methodologies in the Biomedical and Dental Waste Sectors. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2020, 1, 563–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Noto, J. Healthy Buildings vs Green Buildings: What’s the Difference? 16 December 2021. Available online: https://learn.kaiterra.com/en/resources/healthy-buildings-vs-green-buildings-difference (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). IPCC 5th Assessment Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; The Cong, P.; Sanyal, S.; Suksatan, W.; Maneengam, A.; Murtaza, N. Insights into rising environmental concern: Prompt corporate social responsibility to mediate green marketing perspective. Econ. Res. 2022, 35, 5097–5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhenjing, G.; Chupradit, S.; Yen Ku, K.; Nassani, A.; Haffar, M. Impact of Employees’ Workplace Environment on Employees’ Performance: A Multi-Mediation Model. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 890400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Environment Program. Environmental Rule of Law. Available online: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/environmental-rights-and-governance/what-we-do/promoting-environmental-rule-law-0 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Duane, B.; Harford, S.; Ramasubbu, D.; Stancliffe, R.; Pasdeki-Clewer, E.; Lomax, R. Environmentally sustainable dentistry: A brief introduction to sustainable concepts within the dental practice. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 226, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duane, B.; Stancliffe, R.; Miller, F.A.; Sherman, J.; Pasdeki-Clewer, E. Sustainability in Dentistry: A Multifaceted Approach Needed. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veress, A.; Kerekes-Máthé, B.; Székely, M. Environmentally friendly behavior in dentistry. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2023, 96, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.; Mulligan, S. Environmental Sustainability through Good-Quality Oral Healthcare. Int. Dent. J. 2022, 72, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markey, R.; Ravenswood, K.; Webber, D. The Impact of the Quality of the Work Environment on Employees’ Intention to Quit. Economics Working Paper Series 1220, University of West England. Available online: https://www2.uwe.ac.uk/faculties/BBS/BUS/Research/economics2012/1221.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Van Schaack, C.; Ben Dor, T. A comparative study of green building in urban and transitioning rural North Carolina. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2011, 54, 1125–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.H.; Yang, C.H.; Huang, C.T.; Wu, Y.Y. The impact of the carbon tax policy on green building strategy. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 1412–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamani, K. Challenges in the transition toward adaptive water governance. In Water Conservation: Practices, Challenges and Future Implications; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniadou, M. Estimation of Factors Affecting Burnout in Greek Dentists before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Dent. J. 2022, 13, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kats, G. Greening Our Built World: Costs, Benefits, and Strategies; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Langdon, D. The Cost & Benefit of Achieving Green Buildings; Davis Langdon Management Consulting: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jin-Lee, K.; Martin, G.; Sunkuk, K. Cost Comparative Analysis of a New Green Building Code for Residential Project Development. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2014, 140, 05014002. [Google Scholar]

- Dwaikat, L.N.; Ali, K.N. Green buildings cost premium: A review of empirical evidence. Energy Build. 2016, 110, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, A.; Zhang, C.; Chan, A.P.C. Drivers for green building: A review of empirical studies. Habitat Int. 2017, 60, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzoutzas, I.; Maltezou, H.C.; Barmparesos, N.; Tasios, P.; Efthymiou, C.; Assimakopoulos, M.N.; Tseroni, M.; Vorou, R.; Tzermpos, F.; Antoniadou, M.; et al. Indoor Air Quality Evaluation Using Mechanical Ventilation and Portable Air Purifiers in an Academic Dentistry Clinic during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greece. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Andrade, E.; Da Cunha e Silva, D.C.; De Lima, E.A. Environmental noise in hospitals: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 19629–19642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Tziovara, P.; Antoniadou, C. The Effect of Sound in the Dental Office: Practices and Recommendations for Quality Assurance—A Narrative Review. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X. Factors Affecting Green Residential Building Development: Social Network Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J.; Viswesvaran, C.; Wiernik, B.M. The Role of Commitment in Bridging the Gap between Organizational Sustainability and Environmental Sustainability. In Managing Human Resources for Environmental Sustainability; Jackson, S.E., Ones, D.S., Dilchert, S., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 245–283. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.; Liu, X. Pro-Environmental Behavior Research: Theoretical Progress and Future Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 31, 6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilchert, S.; Ones, D.S. Measuring and Improving Environmental Sustainability. In Managing Human Resources for Environmental Sustainability; Jackson, S.E., Ones, D.S., Dilchert, S., Eds.; sJossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 284–327. [Google Scholar]

- Topf, S.; Speekenbrink, M. Follow my example, for better and for worse: The influence of behavioral traces on recycling decisions. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2023, 5, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.; Bergquist, M.; Schultz, W.P. Spillover effects in environmental behaviors, across time and context: A review and research agenda. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, L.M.; Ma, S.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L.X. What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, K.; Grolleau, G.; Ibanez, L. Social Norms and Pro-environmental Behavior: A Review of the Evidence. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzki, S.J.; Steg, L.; Bouman, T. Meta-analytic evidence for a robust and positive association between individuals’ pro-environmental behaviors and their subjective wellbeing. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 123007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulfs, R.; Hahn, R. Corporate Greening beyond Formal Programs, Initiatives, and Systems: A Conceptual Model for Voluntary Pro-environmental Behavior of Employees. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2013, 10, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, J.; Shore, B.M. Conservation Behavior as Outcome of Environmental-Education. J. Environ. Educ. 1975, 6, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuthnot, J. The Roles of Attitudinal and Personality Variables in the Prediction of Environmental Behavior and Knowledge. Environ. Behav. 1977, 9, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, C.T.; Takahashi, B.; Zwickle, A.; Besley, J.C.; Lertpratchya, A.P. Sustainability behaviors among college students: An application of the VBN theory. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klockner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour-A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwartz, S.H. Awareness of Consequences and Influence of Moral Norms on Interpersonal Behavior. Sociometry 1968, 31, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, P.; Staats, H.; Wilke, H.A.M. Explaining proenvironmental intention and behavior by personal norms and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2505–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, M.; Zibarras, L.D.; Stride, C. Using the theory of planned behavior to explore environmental behavioral intentions in the workplace. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, R.; Henderson-Wilson, C.; Ebden, M. Exploring the co-benefits of environmental volunteering for human and planetary health promotion. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2022, 33, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Bae, Y.K.; Chung, J.H. Modeling Social Distance and Activity-Travel Decision Similarity to Identify Influential Agents in Social Networks and Geographic Space and Its Application to Travel Mode Choice Analysis. Transp. Res. Rec. 2020, 2674, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.L.; Tang, C.C.; Lv, X.Y.; Xing, B. Visitor Engagement, Relationship Quality, and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gsottbauer, E.; van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. Environmental Policy Theory Given Bounded Rationality and Other-regarding Preferences. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2011, 49, 63–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klockner, C.A.; Blobaum, A. A comprehensive action determination model toward a broader understanding of ecological behaviour using the example of travel mode choice. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frederiks, E.R.; Stennerl, K.; Hobman, E.V. Household energy use: Applying behavioural economics to understand consumer decision-making and behaviour. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mills, E. Building commissioning: A golden opportunity for reducing energy costs and greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Energy Effic. 2011, 4, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, R.J.; Zou, P.X.W.; Wang, J. Modelling stakeholder-associated risk networks in green building projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G.R.A.; Lynes, J.K. Institutional motivations and barriers to the construction of green buildings on campus: A case study of the University of Waterloo, Ontario. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamison, A. Turning Engineering Green: Sustainable Development and Engineering Education. In Engineering, Development and Philosophy; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, J.K.; Oh, M.W.; Kim, J.T. A method for evaluating the performance of green buildings with a focus on user experience. Energy Build. 2013, 66, 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, B.G.; Shan, M.; Looi, K.Y. Key constraints and mitigation strategies for prefabricated prefinished volumetric construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.G.; Shan, M.; Phua, H.; Chi, S. An exploratory analysis of risks in green residential building construction projects: The case of Singapore. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, P.; Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X.B.; He, Q. Regional variations of credits obtained by LEED 2009 certified green buildings—A country level analysis. Sustainability 2017, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dickinson, J.L.; Crain, R.L.; Reeve, H.K.; Schuldt, J.P. Can evolutionary design of social networks make it easier to be ‘green’? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunmakinde, O.E.; Egbelakin, T.; Sher, W.; Omotayo, T.; Ogunnusi, M. Establishing the limitations of sustainable construction in developing countries: A systematic literature review using PRISMA. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assylbekov, D.; Nadeem, A.; Md Aslam Hossan, A.; Khalfan, M. Factors Influencing Green Building Development in Kazakhstan. Buildings 2021, 11, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichholtz, P.; Quigley, J.M. Green building finance and investments: Practice, policy and research. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2012, 56, 903–904. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.B.; Hwang, B.G.; Hong, N.L. Identifying critical leadership styles of project managers for green building projects. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2016, 16, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peponis, M.; Antoniadou, M.; Pappa, E.; Rahiotis, C.; Varzakas, T. Vitamin D and Vitamin D Receptor Polymorphisms Relationship to Risk Level of Dental Caries. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Masoura, E.; Devetziadou, M.; Rahiotis, C. Ethical Dilemmas for Dental Students in Greece. Dent. J. 2023, 2, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 2, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bingham, A.J.; Witkowsky, P. Deductive and inductive approaches to qualitative data analysis. In Analyzing and Interpreting Qualitative Data: After the Interview; Vanover, C., Mihas, P., Saldaña, J., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2022; pp. 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, L.; Eisend, M. Single versus multiple measurement of attitudes: A meta-analysis of advertising studies validates the single-item measure approach. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursac, Z.; Gauss, C.H.; Williams, D.K. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol. Med. 2008, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spaveras, A.; Antoniadou, M. Awareness of Students and Dentists on Sustainability Issues, Safety of Use and Disposal of Dental Amalgam. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R. Gender and Survey Participation. An Event History Analysis of the Gender Effects of Survey Participation in a Probability-based Multi-wave Panel Study with a Sequential Mixed-mode. Des. Methods Data Anal. 2022, 16, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Women Are Catching Up to Men in Volunteering, and They Engage in More Altruistic Voluntary Activities. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/gender/data/women-are-catching-up-to-men-in-volunteering-and-they-engage-in-more-altruistic-voluntary-activities.htm (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- SMU City Perspectives Team; SMU, Singapore Management University. Why Rewarding Sustainable Behaviour with Money is a Bad Idea. 2022. Available online: https://cityperspectives.smu.edu.sg/article/why-rewarding-sustainable-behaviour-money-bad-idea (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Niebuur, J.; van Lente, L.; Liefbroer, A.C. Determinants of participation in voluntary work: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okun, M.A.; Yeung, E.W.; Brown, S. Volunteering by older adults and risk of mortality: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Aging 2013, 28, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jenkinson, C.E.; Dickens, A.P.; Jones, K.; Thompson-Coon, J.; Taylor, R.S.; Rogers, M. Is volunteering a public health intervention? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the health and survival of volunteers. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 773. Available online: http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-773 (accessed on 20 March 2023). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, N.D.; Damianakis, T.; Kröger, E.; Wagner, L.M.; Dawson, D.R.; Binns, M.A. The benefits associated with volunteering among seniors: A critical review and recommendations for future research. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1505–1533. Available online: http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/a0037610 (accessed on 20 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- International Labour Office Geneva. Manual on the Measurement of Volunteer Work; International Labour Office (ILO): Geneva, Switzernald, 2011; pp. 1–120. ISBN 978-92-2-125071-5. Available online: www.ilo.org/publnsI (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Salamon, L.M.; Sokolowski, S.W.; Megan, A.; Tice, H.S. The State of Global Civil Society and Volunteering: Latest Findings from the Implementation of the UN Nonprofit Handbook; Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2013; Volume 49, p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, R.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, W. How Environmental Knowledge Management Promotes Employee Green Behavior: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 29, 4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Q.C.; Lin, M.L.; Shiao, K.Y.; Wei, C.C.; Jan, Y.L.; Huang, L.T. Changing behaviors: Does knowledge matter? A structural equation modeling study on green building literacy of undergraduates in Taiwan. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2014, 24, 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Truelove, H.B.; Carrico, A.R.; Weber, E.U.; Raimi, K.T.; Vandenbergh, M.P. Positive and negative spillover of pro-environmental behavior: An integrative review and theoretical framework. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 29, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, S.S.; Dhaimade, P.A. Green dentistry: A systematic review of ecological dental practices. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 2599–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, L.; Hegtvedt, K.; Johnson, C.; Parris, C.; Subramanyam, S. When legitimacy shapes environmentally responsible behaviors: Considering exposure to university sustainability initiatives. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watson, L.; Johnson, C.; Hegtvedt, K.; Parris, C. Living green: Examining sustainable dorms and identities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Rogers, A.A.; Krag, M.E.; Zhang, F.; Polyakov, M.; Gibson, F.; Chalak, M.; Pandit, R.; Tapsuwan, S. Consumers’ willingness to pay for renewable energy: A meta-regression analysis. Resour. Energy Econ. 2015, 42, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamilton, E.M. Green Building, Green Behavior? An Analysis of Building Characteristics that Support Environmentally Responsible Behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 409–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Lu, Y.; Gou, Z. Green Building Pro-Environment Behaviors: Are Green Users Also Green Buyers? Sustainability 2017, 9, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antoniadou, M. Economic survival during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oral Hyg. Health 2021, 9, 267–269. [Google Scholar]

- ADA. COVID-19 Economic Impact on Dental Practices. March 2015. Available online: https://www.ada.org/resources/research/health-policy-institute/impact-of-covid-19 (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behavior: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Staddon, S.C.; Cycil, C.; Goulden, M.; Leygue, C.; Spence, A. Intervening to change behavior and save energy in the workplace: A systematic review of available evidence. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 17, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Z.; Lau, S.S.Y.; Prasad, D. Market readiness and policy implications for green buildings: Case study from Hong Kong. J. Green Build. 2013, 8, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelazeem, B.; Abbas, K.S.; Amin, M.A.; El-Shahat, N.A.; Malik, B.; Kalantary, A.; Eltobgy, M. The effectiveness of incentives for research participation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2022, 22, e0267534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Place of Residence | Semester of Studies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males N (%) | Females N (%) | Urban N (%) | Rural N (%) | 10th N (%) | 8th N (%) | 6th N (%) | 4th N (%) | |

| Students | 34 (36.6) | 59 (63.4) | 61 (65.6) | 32 (34.4) | 7 (7.5) | 5 (5.4) | 21 (22.6) | 60 (64.5) |

| Total 93 | ||||||||

| Dentists | 46 (36.5) | 80 (63.5) | 96 (76.2) | 30 (23.8) | ||||

| Total 126 | ||||||||

| Questions Q5–Q9 (Students) and Q8–Q13 (Dentists) and Results According to Gender | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q5. Do you use recycling at home? | ||||||

| Total | Men | Women | ||||

| Students N1 = 93 | Dentists N2 = 126 | Students N1m = 34 | Dentists N2m = 46 | Students N1w = 59 | Dentists N2w = 80 | |

| Yes | 75 (80.64%) | 104 (82.54%) | 27 (79.41%) | 40 (86.96%) | 48 (81.35%) | 64 (80.00%) |

| No | 16 (17.20%) | 22 (17.46%) | 5 (14.70%) | 6 (13.04%) | 11 (18.65%) | 16 (20.00%) |

| I prefer not to answer | 2 (2.16%) | 0 | 2 (5.89%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p-value | 0.16 | 0.32 | ||||

| Q6. Have you ever participated in voluntary environmental actions at home or during your studies? | ||||||

| Yes | 54 (58.06%) | 84 (66.66%) | 19 (55.88%) | 28 (60.86%) | 35 (59.32%) | 56 (70.00%) |

| No | 38 (40.86%) | 40 (31.74%) | 14 (41.17%) | 16 (34.78%) | 24 (40.68%) | 24 (30.00%) |

| I prefer not to answer | 1 (1.08%) | 2 (1.60%) | 1 (2.95%) | 2 (4.36%) | 0 | 0 |

| p-value | 0.41 | 0.13 | ||||

| Q7. Are you aware of what circular economy means in dental practice? | ||||||

| Yes | 20 (21.50%) | 27 (21.42%) | 4 (11.76%) | 11 (23.91%) | 16 (27.11%) | 16 (20.00%) |

| No | 63 (67.74%) | 86 (68.25%) | 26 (76.47%) | 30 (65.21%) | 37 (62.71%) | 56 (70.00%) |

| I prefer not to answer | 10 (10.76%) | 13 (10.33%) | 4 (11.77%) | 5 (10.88%) | 6 (10.18%) | 8 (10%) |

| p-value | 0.22 | 0.24 | ||||

| Q8. Are you aware of the current European Union legislation about mercury use and disposal? | ||||||

| Yes | 28 (30.10%) | 41 (32.54%) | 12 (35.29%) | 17 (36.95%) | 16 (27.11%) | 24 (30.00%) |

| No | 60 (64.51%) | 74 (58.73%) | 21 (61.76%) | 27 (58.69%) | 39 (66.10%) | 47 (58.75%) |

| I prefer not to answer | 5 (5.39%) | 11 (8.73%) | 1 (2.95%) | 2 (4.36%) | 4 (6.79%) | 9 (11.25%) |

| p-value | 0.57 | 0.36 | ||||

| Q9. Are you aware of the current European Union legislation about plastic recycling? | ||||||

| Yes | 20 (21.50%) | 20 (15.87%) | 7 (20.6%) | 9 (19.56%) | 13 (22.0%) | 11 (13.75%) |

| No | 71 (76.34%) | 97 (76.98%) | 27 (79.4%) | 35 (76.09%) | 44 (74.6%) | 62 (77.50%) |

| I prefer not to answer | 2 (2.16%) | 9 (7.14%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (4.35%) | 2 (3.4%) | 7 (8.75%) |

| p-value | 0.54 | 0.45 | ||||

| Questions Q5–Q9 (Students) and Q8–Q13 (Dentists) and Results According to Place of Origin/Dentistry Practice | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q5. Do you use recycling at home? | ||||||

| Total | Urban Areas | Non-Urban Areas | ||||

| Students N1 = 93 | Dentists N2 = 126 | Students N1urban = 61 | Dentists N2urban = 96 | Students N1nonurban = 32 | Dentists N2nonurban = 30 | |

| Yes | 75 (80.64%) | 104 (82.54%) | 48 (78.68%) | 80 (83.33%) | 27 (84.37%) | 24 (80.00%) |

| No | 16 (17.20%) | 22 (17.46%) | 12 (19.67%) | 16 (16.67%) | 4 (12.50%) | 6 (20.00%) |

| I prefer not to answer | 2 (2.16%) | 0 | 1 (1.65%) | 0 | 1 (3.13%) | 0 |

| p-value | 0.63 | 0.67 | ||||

| Q6. Have you ever participated in voluntary environmental actions at home or during your studies? | ||||||

| Yes | 54 (58.1%) | 84 (66.66%) | 35 (57.4%) | 62 (64.58%) | 19 (59.4%) | 22 (73.33%) |

| No | 38 (40.9%) | 40 (31.74%) | 25 (41.0%) | 32 (33.33%) | 13 (40.6%) | 8 (26.67%) |

| I prefer not to answer | 1 (1.1%) | 2 (1.60%) | 1 (1.6%) | 2 (2.09%) | 0 | 0 |

| p-value | 0.76 | 0.55 | ||||

| Q7. Are you aware of what circular economy means in dental practices? | ||||||

| Yes | 20 (21.5%) | 27 (21.43%) | 14 (22.95%) | 17 (17,70%) | 6 (18.75%) | 10 (33.33%) |

| No | 63 (67.7%) | 86 (68.25%) | 41 (67.21%) | 70 (72.91%) | 22 (68.75%) | 16 (53.33%) |

| I prefer not to answer | 10 (10.8%) | 13 (10.32%) | 6 (9.84%) | 9 (9.39%) | 4 (12.5%) | 4 (13.34%) |

| p-value | 0.85 | 0.19 | ||||

| Q8. Are you aware of the current European Union legislation about mercury use and disposal? | ||||||

| Yes | 28 (30.10%) | 41 (32.54%) | 19 (31.14%) | 34 (35.42%) | 9 (28.1%) | 7 (23.33%) |

| No | 60 (64.51%) | 74 (58.73%) | 38 (62.29%) | 56 (58.33%) | 22 (68.8%) | 18 (60.00%) |

| I prefer not to answer | 5 (5.39%) | 11 (8.73%) | 4 (6.57%) | 6 (6.25%) | 1 (3.1%) | 5 (16.67%) |

| p-value | 0.71 | 0.14 | ||||

| Q9. Are you aware of the current European Union legislation about plastic recycling? | ||||||

| Yes | 20 (21.50%) | 20 (15.87%) | 14 (22.95%) | 16 (16.67%) | 6 (18.75%) | 4 (13.33%) |

| No | 71 (76.34%) | 97 (76.98%) | 45 (73.77%) | 74 (77.08%) | 26 (81.25%) | 23 (76.67%) |

| I prefer not to answer | 2 (2.16%) | 9 (7.14%) | 2 (3.28%) | 6 (6.25%) | 0 | 3 (10.00%) |

| p-value | 0.50 | 0.74 | ||||

| Gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dental Students | Males N (%) | Females N (%) | p Value * |

| Increased costs in utility networks | |||

| Neutral | 6 (17.6%) | 20 (33.9%) | 0.02 |

| Extremely insignificant | 5 (14.7%) | 1 (1.7%) | |

| Extremely significant | 23 (67.6%) | 38 (64.4%) | |

| Lack of environmental awareness of manufacturers | |||

| Neutral | 6 (17.6%) | 2 (3.4%) | 0.057 |

| Extremely insignificant | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.1%) | |

| Extremely significant | 28 (82.4%) | 54 (91.5%) | |

| Poor wastewater management | |||

| Neutral | 7 (20.6%) | 2 (3.4%) | 0.01 |

| Extremely insignificant | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (6.8%) | |

| Extremely significant | 27 (79.4%) | 53 (89.8%) | |

| Dentists | Most environmentally damaging practice in a dental practice | ||

| Males N (%) | Females N (%) | p-value | |

| Wasted energy | |||

| No | 28 (60.87%) | 32 (40.00%) | 0.024 |

| Yes | 18 (39.13%) | 48 (60.00%) | |

| Use of unapproved disinfection products | |||

| No | 36 (78.26%) | 48 (60.00%) | 0.036 |

| Yes | 10 (21.74%) | 32 (40.00%) | |

| Place of Residence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Students | Urban | Rural N (%) | p Value * |

| Lack of financial support | |||

| Neutral | 4 (6.6%) | 4 (12.5%) | 0.02 |

| Extremeley insignificant | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (12.5%) | |

| Extremely significant | 57 (93.4%) | 24 (75.0%) | |

| Low level of “green” design in buildings | |||

| Neutral | 2 (3.3%) | 4 (12.5%) | 0.03 |

| Extremely insignificant | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (6.3%) | |

| Extremely significant | 59 (96.7%) | 26 (81.2%) | |

| Reduced profits of green dental practice in the near future | |||

| Neutral | 12 (19.7%) | 14 (43.8%) | 0.04 |

| Extremely insignificant | 11 (18.0%) | 3 (9.4%) | |

| Extremely significant | 38 (62.3%) | 15 (46.9%) | |

| Negligible benefits for the reputation of the business by today’s standards | |||

| Neutral | 15 (24.5%) | 14 (43.8%) | 0.02 |

| Extremeley insignificant | 2 (3.3%) | 5 (15.6%) | |

| Extremeley significant | 44 (72.2%) | 13 (40.6%) | |

| Lack of continuous education and training seminars on green dentistry | |||

| Neutral | 9 (14.8%) | 4 (12.5%) | 0.05 |

| Extremely insignificant | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (9.4%) | |

| Extremely significant | 52 (85.2%) | 25 (78.1%) | |

| Dentists | |||

| Urban N (%) | Rural N (%) | p-value | |

| Increased costs in utility networks | |||

| Neutral | 19 (19.8%) | 11 (34.4%) | 0.08 |

| Extremely insignificant | 12 (4.9%) | 3 (12.5%) | |

| Extremely significant | 43 (70.5%) | 65 (67.7%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antoniadou, M.; Chrysochoou, G.; Tzanetopoulos, R.; Riza, E. Green Dental Environmentalism among Students and Dentists in Greece. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9508. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129508

Antoniadou M, Chrysochoou G, Tzanetopoulos R, Riza E. Green Dental Environmentalism among Students and Dentists in Greece. Sustainability. 2023; 15(12):9508. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129508

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntoniadou, Maria, Georgios Chrysochoou, Rafael Tzanetopoulos, and Elena Riza. 2023. "Green Dental Environmentalism among Students and Dentists in Greece" Sustainability 15, no. 12: 9508. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129508