Sustainability in Project Management and Project Success with Virtual Teams: A Quantitative Analysis Considering Stakeholder Engagement and Knowledge Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Project Success (PS)

2.1.1. The Perspective of Sustainability in Project Management (SPM)

2.1.2. The Perspective of Stakeholder Engagement (SE)

2.1.3. The Perspective of Knowledge Management (KM)

2.2. Sustainability in Project Management: The Perspective of Stakeholder Engagement and Knowledge Management

2.3. Virtual Team Environment

2.3.1. Virtual Teams: The Perspective of Sustainability in Project Management Influence on Project Success

2.3.2. Virtual Teams: The Perspective of Stakeholder Engagement Influence on Project Success

2.3.3. Virtual Teams: The Perspective of Knowledge Management Influence on Project Success

2.4. Stakeholder Engagement and Knowledge Management

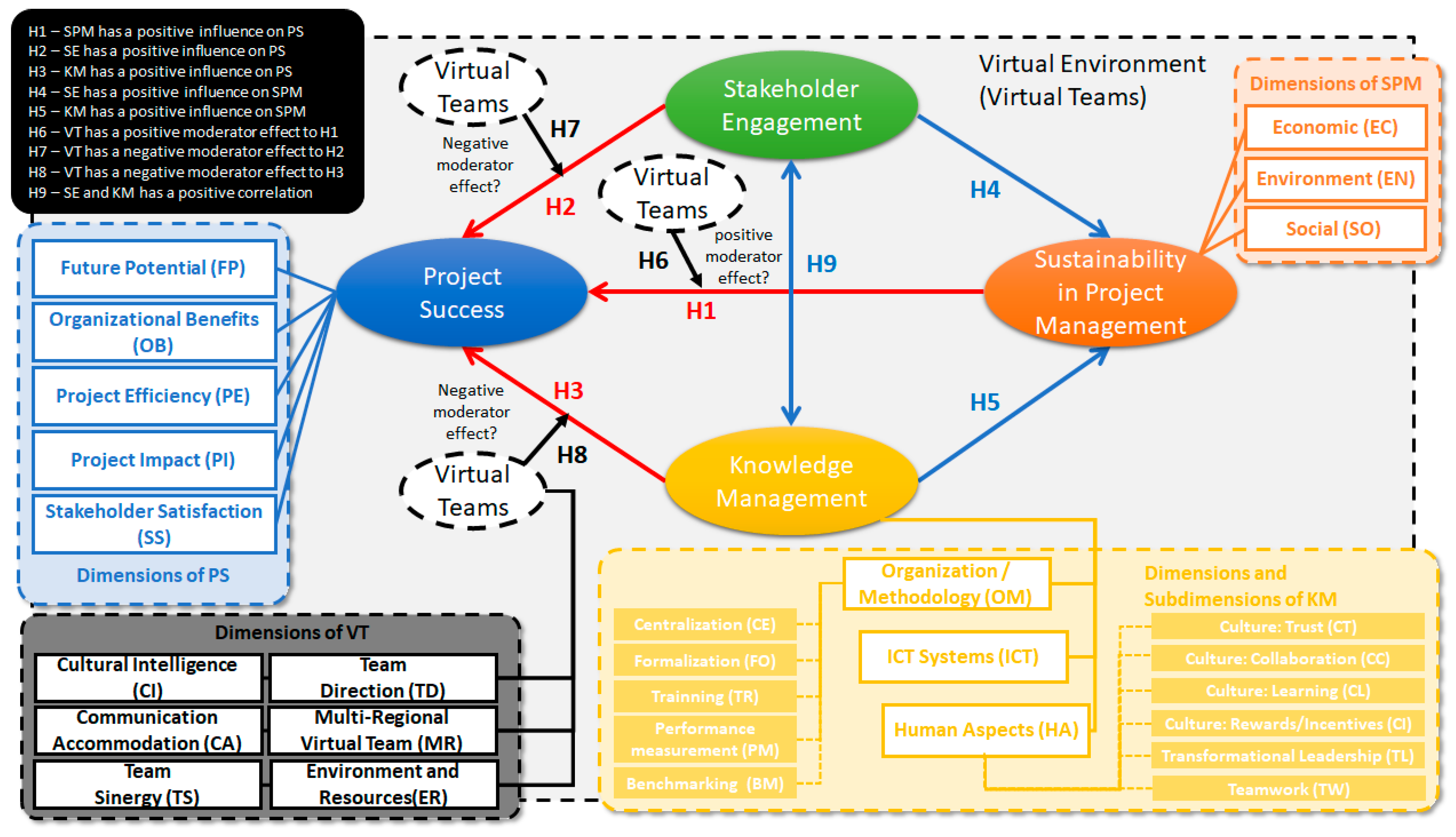

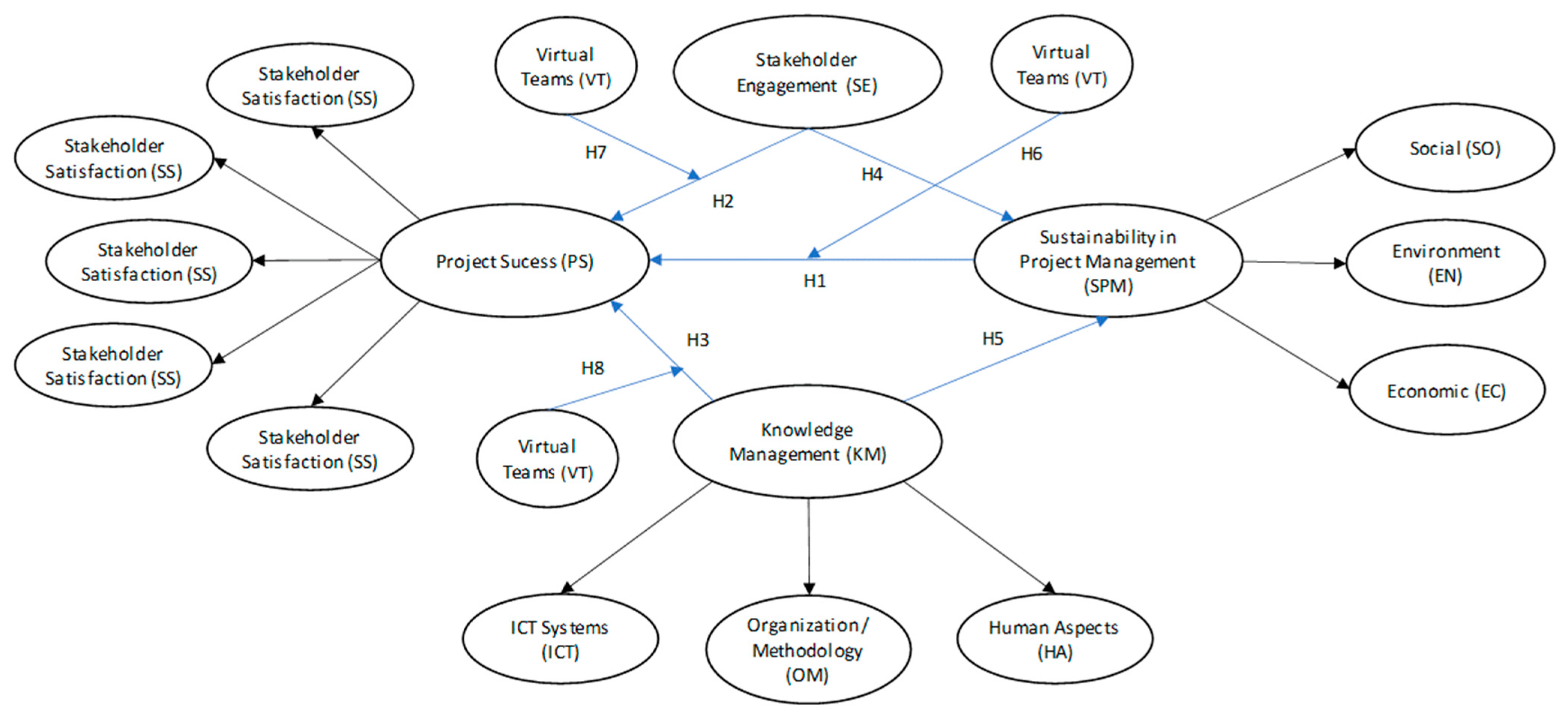

2.5. Research Model and Hypothesis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Sample Characteristics

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Structural Equation Modeling

4. Results

4.1. Sample Database Description

4.2. Sample Descriptive Analysis

4.3. First-Order Construct Descriptive Analysis

4.4. Mesurement Model (Outer Model)

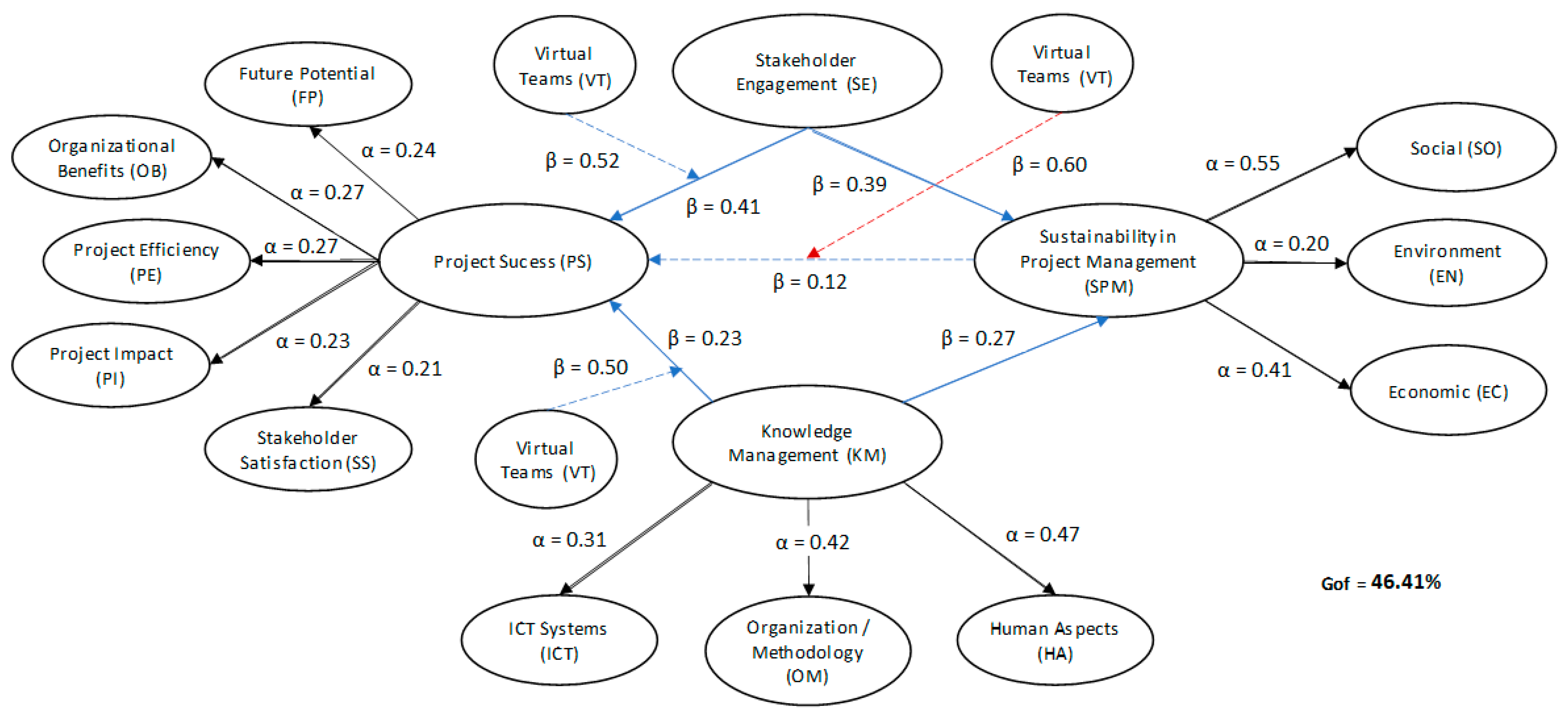

4.5. Structural Model (Inner Model) and Results

- Related to Sustainability in Project Management (SPM):

- Higher levels of KM were found to have a significant (p-value < 0.001) and positive (β = 0.27 [0.12; 0.43]) influence on SPM.

- Higher levels of SE were found to have a significant (p-value < 0.001) and positive (β = 0.39 [0.24; 0.53]) influence on SPM.

- The correlation between SE and KM is 0.6435.

- Indeed, KM and SE explained 31.73% of the variability in SPM.

- Related to Project Success (PS) in Virtual Team Environment (VT):

- Higher levels of KM were found to have a significant (p-value = 0.001) and positive (β = 0.23 [0.11; 0.37]) influence on PS.

- Higher levels of SE were found to have a significant (p-value < 0.001) and positive (β = 0.39 [0.24; 0.53]) influence on PS.

- However, higher levels of SPM were not found to have a significative influence (p-value > 0.05) on PS.

- In the same path, VTs were not found to have a significant moderating (p-value > 0.05) effect on the relationship between the constructs.

- The correlation between SE and KM is 0.6435.

- KM, SE, SPM, and their interactions with VT explained 42.06% of the variability in PS.

4.6. Model Hypotheses Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

- Both stakeholder engagement (SE) and knowledge management (KM) have a significant positive influence on project success (PS) and on sustainability in project management (SPM).

- The relationship between KM, SE, SPM, and PS was consistent irrespective of whether the team was working in a virtual or co-located environment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Item | Legend | Question | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Teams (VT) | Cultural Intelligence (CI) | VT-CI1 | 5.1.1 | I know the legal and economic systems of other cultures. |

| VT-CI2 | 5.1.2 | I know the rules (e.g., vocabulary, grammar) of other languages. | ||

| VT-CI3 | 5.1.3 | I know the cultural values and religious beliefs of other cultures. | ||

| VT-CI4 | 5.1.4 | I know the rules for expressing nonverbal behaviors in other cultures. | ||

| VT-CI 5 | 5.1.5 | I am conscious of the cultural background I use when interacting with people with different cultural backgrounds. | ||

| VT-CI6 | 5.1.6 | I adjust my cultural knowledge as I interact with people from a culture that is unfamiliar to me. | ||

| VT-CI7 | 5.1.7 | I am conscious of the cultural knowledge I apply to cross-cultural interactions. | ||

| VT-CI8 | 5.1.8 | I check the accuracy of my cultural knowledge as I interact with people from different cultures. | ||

| VT-CI9 | 5.1.9 | I enjoy interacting with people from different cultures. | ||

| VT-CI10 | 5.1.10 | I am confident that I can socialize with locals in a culture that is unfamiliar to me. | ||

| VT-CI11 | 5.1.11 | I am sure I can deal with the stresses of adjusting to a culture that is new to me. | ||

| VT-CI12 | 5.1.12 | I enjoy living in cultures that are unfamiliar to me. | ||

| VT-CI13 | 5.1.13 | I am confident that I can get accustomed to the shopping conditions in a different culture. | ||

| VT-CI14 | 5.1.14 | I change my verbal behavior (e.g., accent, tone) when a cross-cultural interaction requires it. | ||

| VT-CI15 | 5.1.15 | I use pause and silence differently to suit different cross-cultural situations. | ||

| VT-CI16 | 5.1.16 | I vary the rate of my speaking when a cross-cultural situation requires it. | ||

| VT-CI17 | 5.1.17 | I change my nonverbal behavior when a cross-cultural situation requires it. | ||

| VT-CI18 | 5.1.18 | I alter my facial expressions when a cross-cultural situation requires it. | ||

| Communication Accommodation (CA) | VT-CA1 | 5.2.1 | I try to match the communication style of other members in the GVT. | |

| VT-CA2 | 5.2.2 | I show interest when speaking to others in the GVT. | ||

| VT-CA3 | 5.2.3 | I can easily adjust when communicating to others in the GVT. | ||

| VT-CA4 | 5.2.4 | I respond constructively when communicating with others in the GVT. | ||

| VT-CA5 | 5.2.5 | I am open-minded in evaluating the feedback given to me by other members of the GVT. | ||

| VT-CA6 | 5.2.6 | I adjust my communication styles with others in the GVT. | ||

| VT-CA7 | 5.2.7 | I show my willingness to listen when communicating with others in the GVT. | ||

| Team Sinergy (TS) | VT-TS1 | 5.3.1 | He/she openly shares information about the task. | |

| VT-TS2 | 5.3.2 | He/she demonstrates flexibility with others. | ||

| VT-TS3 | 5.3.3 | He/she helps actively in resolving conflicts in the team. | ||

| VT-TS4 | 5.3.4 | He/she is good in communicating when making decisions. | ||

| VT-TS5 | 5.3.5 | He/she contributes significantly to the team. | ||

| VT-TS6 | 5.3.6 | He/she promotes friendly team climate. | ||

| VT-TS7 | 5.3.7 | He/she is effective in coordinating group efforts. | ||

| VT-TS8 | 5.3.8 | He/she is cooperative with other team members. | ||

| VT-TS9 | 5.3.9 | He/she helps team members beyond what is required. | ||

| Team Direction (TD) | VT-TD1 | 5.4.1 | He/she sets goals effectively. | |

| VT-TD2 | 5.4.2 | He/she continually improves. | ||

| VT-TD3 | 5.4.3 | He/she is effective in problem-solving. | ||

| VT-TD4 | 5.4.4 | He/she sets high quality standards. | ||

| VT-TD5 | 5.4.5 | He/she focuses on common team goals. | ||

| VT-TD6 | 5.4.6 | He/she is enthusiasm for team direction and performance. | ||

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) | VT-MR1 | 5.5.1 | I strengthen ties between other teammates and myself. | |

| VT-MR2 | 5.5.2 | It is challenging to deal with different languages in virtual team (in your organization). | ||

| VT-MR3 | 5.5.3 | It is challenging to deal with different cultures in virtual team (in your organization). | ||

| VT-MR4 | 5.5.4 | It is challenging to deal with different time zones in virtual team collaborations (in your organization). | ||

| VT-MR5 | 5.5.5 | It is challenging to use virtual technologies in virtual team collaborations (in your organization). | ||

| VT-MR6 | 5.5.6 | It is challenging to establish and respect standards/rules for meetings and team collaboration. | ||

| Environment and Resources (ER) | VT-ER1 | 5.6.1 | There was a reduction in the administrative expenses of the project (natural resources such as energy, water, others). | |

| VT-ER2 | 5.6.2 | There was an increase in productivity considering that there was no displacement. | ||

| VT-ER3 | 5.6.3 | There was a reduction in environmental impacts considering that there was no displacement. | ||

| VT-ER4 | 5.6.4 | There was a reduction in environmental impacts considering that there was no use of an administrative office. | ||

| VT-ER5 | 5.6.5 | There was increased productivity due to remote work. | ||

| VT-ER6 | 5.6.6 | There was increased productivity due to the satisfaction and well-being of the team. | ||

| Construct | Item | Legend | Question | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability in Project Management (SPM) | Economic (EC) | (The project considers relevant/applied… Is it Important?) | ||

| SPM-EC1 | 6.1.1 | Financial performance (return on investments, solvency, profitability, and liquidity) | ||

| SPM-EC2 | 6.1.2 | Financial benefits of good practices (social, environmental, health and safety, job creation, education, and training) | ||

| SPM-EC3 | 6.1.3 | Business ethics (fair trade, relationship with competition and anti-crime policies, codes of conduct, bribery and corruption, technical and legal requirements, tax payments) | ||

| SPM-EC4 | 6.1.4 | Cost management (resources) | ||

| SPM-EC5 | 6.1.5 | Management of the company’s relationship with customers (marketing and brand management, market share, management opportunities, risk management, and pricing) | ||

| SPM-EC6 | 6.1.6 | Participation and involvement of stakeholders (corporate governance) | ||

| SPM-EC7 | 6.1.7 | Innovation management (research and development, consumption patterns, production, productivity, and flexibility) | ||

| SPM-EC8 | 6.1.8 | Economic performance (profit sharing, GDP) | ||

| SPM-EC9 | 6.1.9 | Culture of the organization and its management (heritage) | ||

| SPM-EC10 | 6.1.10 | Economics and environmental accounting | ||

| SPM-EC11 | 6.1.11 | Management of intangibles | ||

| SPM-EC12 | 6.1.12 | Internationalization | ||

| Environment (EN) | (The project considers relevant/applied… Is it Important?) | |||

| SPM-EN1 | 6.2.1 | Natural resources (reduction of resource use, material input and output minimization, reduction of waste production and soil contamination, impact reduction) | ||

| SPM-EN2 | 6.2.2 | Energy (generation, use, distribution, and transmission of energy, global warming) | ||

| SPM-EN3 | 6.2.3 | Water (water quality, reduction of liquid waste, risks) | ||

| SPM-EN4 | 6.2.4 | Biodiversity (air, protection of oceans, lakes, coasts, forests) | ||

| SPM-EN5 | 6.2.5 | Management systems of environmental policies (environmental obligations, environmental adaptation, environmental infractions) | ||

| SPM-EN6 | 6.2.6 | Management of impacts on the environment and the life cycle of products and services (analysis of product disassembly, post-sale tracking, reverse logistics) | ||

| SPM-EN7 | 6.2.7 | Eco-efficiency (business opportunities for products and services, environmental footprint) | ||

| SPM-EN8 | 6.2.8 | Environmental justice and responsibility (intergenerational equity, compromise with the improvement of environmental quality) | ||

| SPM-EN9 | 6.2.9 | Environmental education and training | ||

| SPM-EN10 | 6.2.10 | High-risk projects, climate strategy and governance | ||

| SPM-EN11 | 6.2.11 | Environmental reports | ||

| Social (SO) | (The project considers relevant/applied… Is it Important?) | |||

| SPM-O1 | 6.3.1 | Labor practices (health, safety and working conditions, training and education) | ||

| SPM-O2 | 6.3.2 | Labor practices (relations with employees, employment, diversity, opportunity, remuneration, benefits and career opportunities) | ||

| SPM-O3 | 6.3.3 | Relationships with the local community (impacts, child labor, human rights, non-discrimination, indigenous rights, forced and compulsory labor) | ||

| SPM-O4 | 6.3.4 | Engagement of stakeholders | ||

| SPM-O5 | 6.3.5 | Financing and construction of social action (philanthropy and corporate citizenship, governmental social projects, leadership and social influence) | ||

| SPM-O6 | 6.3.6 | Society (competition and pricing policies, anti-bribery and anti-corruption practices and suborn) | ||

| SPM-O7 | 6.3.7 | Concepts of social justice | ||

| SPM-O8 | 6.3.8 | Relationships with suppliers and contractors (selection, evaluation, partnership) | ||

| SPM-O9 | 6.3.9 | Society (contribution to social campaigns) | ||

| SPM-O10 | 6.3.10 | Products and services (responsibility, consumer health and safety, marketing, respect and privacy) | ||

| SPM-O11 | 6.3.11 | Human rights (freedom of association and collective bargaining and relationship with trade unions) | ||

| SPM-O12 | 6.3.12 | Human rights (strategy and management, disciplinary procedures) | ||

| SPM-O13 | 6.3.13 | Social Reports | ||

| Construct | Legend | Question | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder Engagement (SE) | SE1 | 7.1 | Project Management team explained project objectives and implications to all stakeholders |

| SE2 | 7.2 | Project management team carefully considered stakeholders opinions and views | |

| SE3 | 7.3 | Project Management team actively built a good relationship with stakeholders | |

| SE4 | 7.4 | Project Management team operated an effective communication system for the project | |

| SE5 | 7.5 | Project Management team implemented a governance system for the project | |

| SE6 | 7.6 | Stakeholder interests were carefully considered throughout the project lifecycle | |

| SE7 | 7.7 | Key stakeholders were empowered to participate in the decision-making process | |

| SE8 | 7.8 | Involving relevant project stakeholders at the inception stage and whenever necessary to refine project mission | |

| SE9 | 7.9 | Formulating appropriate strategies to manage/engage different stakeholders | |

| SE10 | 7.10 | Considering corporate social responsibilities (paying attention to economic, legal, environmental, and ethical issues) | |

| Construct | Item | Subitem | Legend | Question | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Management (KM) | Organization/Methodology (OM) | Centralization (CE) | Our company members… | ||

| KM-OM-CE1 | 8.1.1.1 | can take actions without a superior | |||

| KM-OM-CE2 | 8.1.1.2 | are encouraged to make their own decisions | |||

| KM-OM-CE3 | 8.1.1.3 | do not need to refer to someone else | |||

| KM-OM-CE4 | 8.1.1.4 | do not need to ask their supervisors before taking actions | |||

| KM-OM-CE5 | 8.1.1.5 | can make decisions without approval | |||

| Formalization (FO) | In our company… | ||||

| KM-OM-FO1 | 8.1.2.1 | there are many activities that are not covered by some formal procedures | |||

| KM-OM-FO2 | 8.1.2.2 | contacts with organizational members are made on a formal or planned basis | |||

| KM-OM-FO3 | 8.1.2.3 | rules and procedures are typically written | |||

| Training (TR) | Our organization… | ||||

| KM-OM-TR1 | 8.1.3.1 | places people at the right job position | |||

| KM-OM-TR2 | 8.1.3.2 | provides training for sharing of knowledge | |||

| KM-OM-TR3 | 8.1.3.3 | provides continuous training program within the organization | |||

| KM-OM-TR4 | 8.1.3.4 | provides continuous training program outside the organization | |||

| KM-OM-TR5 | 8.1.3.5 | facilitates us to use knowledge management systems | |||

| KM-OM-TR6 | 8.1.3.6 | is able to retain outstanding staff | |||

| Performance measurement (PM) | Our company employs a procedure to measure… | ||||

| KM-OM-PM1 | 8.1.4.1 | distribution of knowledge within the organization | |||

| KM-OM-PM2 | 8.1.4.2 | amount of reports generated on knowledge activity by employees | |||

| KM-OM-PM3 | 8.1.4.3 | number of relationships established due to knowledge systems and networking | |||

| KM-OM-PM4 | 8.1.4.4 | number of employees accepting knowledge activity as part of their daily work | |||

| KM-OM-PM5 | 8.1.4.5 | changes of job performance due to proper management of knowledge in place | |||

| KM-OM-PM6 | 8.1.4.6 | performance of target activities to previously set baseline | |||

| KM-OM-PM7 | 8.1.4.7 | job performance data and information | |||

| KM-OM-PM8 | 8.1.4.8 | actual performance improvement and reward/recognition | |||

| Benchmarking (BM) | Our company has processes for… | ||||

| KM-OM-BM1 | 8.1.5.1 | generating new knowledge from existing knowledge | |||

| KM-OM-BM2 | 8.1.5.2 | using feedback from past experience to improve future projects | |||

| KM-OM-BM3 | 8.1.5.3 | exchanging knowledge with external partners | |||

| KM-OM-BM4 | 8.1.5.4 | acquiring knowledge about new products and services within our industry | |||

| KM-OM-BM5 | 8.1.5.5 | acquiring knowledge about competitors within our industry | |||

| KM-OM-BM6 | 8.1.5.6 | benchmarking performance amongst employees and departments | |||

| KM-OM-BM7 | 8.1.5.7 | identifying and upgrading best practices | |||

| KM-OM-BM8 | 8.1.5.8 | encouraging employees to benchmark best practices of other organizations | |||

| ICT Systems (ICT) | Our company provides IT support for… | ||||

| KM-ICT1 | 8.2.1 | collaborative works regardless of time and place | |||

| KM-ICT2 | 8.2.2 | communication amongst organizational members | |||

| KM-ICT3 | 8.2.3 | searching for and accessing necessary information | |||

| KM-ICT4 | 8.2.4 | simulation and prediction | |||

| KM-ICT5 | 8.2.5 | systematic storing of data and information | |||

| Human Aspects (HA) | Culture: Trust (CT) | Our company members… | |||

| KM-HA-CT1 | 8.3.1.1 | are generally trustworthy | |||

| KM-HA-CT2 | 8.3.1.2 | have reciprocal faith in the intention and behaviors of other members | |||

| KM-HA-CT3 | 8.3.1.3 | have reciprocal faith in the behaviors of others to work towards organizational goal | |||

| KM-HA-CT4 | 8.3.1.4 | have reciprocal faith in the behaviors of others to work towards organizational goal | |||

| KM-HA-CT5 | 8.3.1.5 | have reciprocal faith in the decision of others towards organizational interest than individual interest | |||

| KM-HA-CT6 | 8.3.1.6 | have relationship based on reciprocal faith | |||

| Culture: Collaboration (CC) | Our organization members… | ||||

| KM-HA-CC1 | 8.3.2.1 | Our organization members are satisfied with the degree of collaboration | |||

| KM-HA-CC2 | 8.3.2.2 | Our organization members are supportive of each other | |||

| KM-HA-CC3 | 8.3.2.3 | Our organization members are helpful | |||

| KM-HA-CC4 | 8.3.2.4 | There is a willingness to collaborate across organizational units within our organization | |||

| KM-HA-CC5 | 8.3.2.5 | There is a willingness to accept responsibility for failure | |||

| Culture: Learning (CL) | Our company… | ||||

| KM-HA-CL1 | 8.3.3.1 | provides various formal training programs related to the performance of our duties | |||

| KM-HA-CL2 | 8.3.3.2 | provides opportunities for informal individual development other than formal training such as work assignment and job rotation | |||

| KM-HA-CL3 | 8.3.3.3 | encourages people to attend seminars, symposia and so on | |||

| KM-HA-CL4 | 8.3.3.4 | provides various programs such as clubs and community gathering | |||

| KM-HA-CL5 | 8.3.3.5 | members are satisfied by the contents of job training | |||

| KM-HA-CL6 | 8.3.3.6 | members are satisfied with the self-development programs | |||

| Culture: Rewards/ Incentives (CI) | In our company… | ||||

| KM-HA-CI1 | 8.3.4.1 | it is more likely that I will be given a pay rise or promotion if I finish a large amount of work | |||

| KM-HA-CI2 | 8.3.4.2 | it is more likely that I will be given a pay rise or promotion if I do a high- quality work | |||

| KM-HA-CI3 | 8.3.4.3 | getting work done quickly increase my chances of a pay rise or promotion | |||

| KM-HA-CI4 | 8.3.4.4 | getting work done on time is rewarded with high pay | |||

| KM-HA-CI5 | 8.3.4.5 | when I finish my job on time, my job is more secured | |||

| KM-HA-CI6 | 8.3.4.6 | in my team, knowledge-sharing is strongly encouraged | |||

| Transformational Leadership (TL) | In our company… | ||||

| KM-HA-TL1 | 8.3.5.1 | I feel comfortable with the concept of shared leadership | |||

| KM-HA-TL2 | 8.3.5.2 | our organizational leaders motivate employees to share knowledge | |||

| KM-HA-TL3 | 8.3.5.3 | our organizational leaders build up trust amongst employees to share knowledge | |||

| KM-HA-TL4 | 8.3.5.4 | our organizational leaders promote initiatives to acquire knowledge | |||

| KM-HA-TL5 | 8.3.5.5 | our organization actively develops leadership skills of our staff | |||

| KM-HA-TL6 | 8.3.5.6 | knowledge is acquired by one-to-one mentoring | |||

| KM-HA-TL7 | 8.3.5.7 | informal conversations and meeting are used for knowledge-sharing | |||

| KM-HA-TL8 | 8.3.5.8 | our organization provides rewards and incentives for sharing knowledge | |||

| Teamwork (TW) | In our company… | ||||

| KM-HA-TW1 | 8.3.6.1 | I feel comfortable with the concept of shared leadership | |||

| KM-HA-TW2 | 8.3.6.2 | I feel comfortable with the decision-making process within the team | |||

| KM-HA-TW3 | 8.3.6.3 | I spend time with team members to clarify the expectations of the team | |||

| KM-HA-TW4 | 8.3.6.4 | team exercises good judgement during decision-making process | |||

| KM-HA-TW5 | 8.3.6.5 | team members provide input/thoughts throughout the project | |||

| KM-HA-TW6 | 8.3.6.6 | I help my team whenever anyone has difficulties in performing tasks | |||

| Construct | Item | Legend | Question | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project Success (PS) | Future Potential (FP) | PS-FP1 | 9.1.1 | Enabling of other project work in future. |

| PS-FP2 | 9.1.2 | Resources mobilized and used as planned. | ||

| PS-FP3 | 9.1.3 | Improvement in organizational capability. | ||

| PS-FP4 | 9.1.4 | Motivated for future projects. | ||

| Organizational Benefits (OB) | PS-OB1 | 9.2.1 | Adhered to defined procedures. | |

| PS-OB2 | 9.2.2 | Learned from project. | ||

| PS-OB3 | 9.2.3 | New understanding/knowledge gained. | ||

| PS-OB4 | 9.2.4 | End product used as planned. | ||

| PS-OB5 | 9.2.5 | The project satisfies the needs of users. | ||

| Project Efficiency (PE) | PS-PE1 | 9.3.1 | Finished within budget. | |

| PS-PE2 | 9.3.2 | Met planned quality standards. | ||

| PS-PE3 | 9.3.3 | Met safety standards. | ||

| PS-PE4 | 9.3.4 | Minimum number of agreed scope changes. | ||

| PS-PE5 | 9.3.5 | Finished on time. | ||

| PS-PE6 | 9.3.6 | Complied with environmental regulations. | ||

| PS-PE7 | 9.3.7 | Activities carried out as scheduled. | ||

| PS-PE8 | 9.3.8 | Cost effectiveness of work. | ||

| Project Impact (PI) | PS-PI1 | 9.4.1 | Project’s impacts on beneficiaries are visible. | |

| PS-PI2 | 9.4.2 | Project achieved its purpose. | ||

| PS-PI3 | 9.4.3 | Project has good reputation. | ||

| PS-PI4 | 9.4.4 | End-user satisfaction. | ||

| Stakeholder Satisfaction (SS) | PS-SS1 | 9.5.1 | Met client’s requirements. | |

| PS-SS2 | 9.5.2 | Steering group satisfaction. | ||

| PS-SS3 | 9.5.3 | Sponsor satisfaction. | ||

| PS-SS4 | 9.5.4 | Met organizational objectives. | ||

Appendix B

| Variables | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Brazilian | 174 | 82.86% |

| Dual nationality, one of them being Brazilian | 29 | 13.81% | |

| Others | 7 | 3.33% | |

| Age Range | From 21 to 30 years old | 13 | 6.19% |

| From 31 to 40 years old | 43 | 20.48% | |

| From 41 to 50 years old | 77 | 36.67% | |

| From 51 to 60 years old | 51 | 24.29% | |

| 61 years or older | 26 | 12.38% | |

| Gender | Female | 62 | 29.52% |

| Male | 147 | 70.00% | |

| Other | 1 | 0.48% | |

| Experience working with projects | Less than 1 year | 9 | 4.29% |

| From 1 to 5 years | 30 | 14.29% | |

| From 6 to 10 years | 29 | 13.81% | |

| From 11 to 15 years | 28 | 13.33% | |

| More than 15 years | 114 | 54.29% | |

| Experience working with projects in a virtual team environment. | Less than 1 year | 27 | 12.86% |

| From 1 to 5 years | 113 | 53.81% | |

| From 6 to 10 years | 15 | 7.14% | |

| More than 10 years | 28 | 13.33% | |

| Never worked on projects with a virtual team environment | 27 | 12.86% | |

| Variables | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time working on projects with a virtual team environment | Not at this moment | 46 | 25.14% |

| For 1 years or less | 41 | 22.40% | |

| For 5 years or less | 73 | 39.89% | |

| For 10 years or less | 6 | 3.28% | |

| For More that 10 years | 17 | 9.29% | |

| Type of participation/role in the project | Leader or Project Manager | 102 | 55.74% |

| Team Member | 69 | 37.70% | |

| Others | 12 | 6.56% | |

| Personal location during the project | Southeast region | 130 | 71.04% |

| International | 19 | 10.38% | |

| North, Northeast, or Central-West regions | 13 | 7.10% | |

| South region | 11 | 6.01% | |

| Brazil (multi-local/no fixed location) | 10 | 5.46% | |

| Location of team members during the project | Southeast region | 67 | 36.61% |

| Brazil (multi-local/no fixed location) | 64 | 34.97% | |

| International | 41 | 22.40% | |

| North, Northeast, or Central-West regions | 11 | 6.01% | |

| Team Size | Up to 10 members | 76 | 41.53% |

| 11 to 50 members | 71 | 38.80% | |

| 51 to 100 members | 15 | 8.20% | |

| 101 to 500 members | 16 | 8.74% | |

| 501 or more members | 5 | 2.73% | |

| Organization Size | Up to 10 members | 49 | 26.78% |

| 11 to 50 members | 35 | 19.13% | |

| 51 to 100 members | 18 | 9.84% | |

| 101 to 500 members | 22 | 12.02% | |

| 501 to 1000 members | 9 | 4.92% | |

| 1001 or more members | 50 | 27.32% | |

| Project Budget | Up to R$100,000 | 24 | 13.11% |

| R$101,000 to R$500,000 | 41 | 22.40% | |

| R$501,000 to R$1,000,000 | 36 | 19.67% | |

| R$1,000,001 to R$500,000,000 | 67 | 36.61% | |

| R$500,000,001 to R$1 billion | 6 | 3.28% | |

| Above R$1 billion | 9 | 4.92% | |

| Sector | Private | 139 | 75.96% |

| Public | 18 | 9.84% | |

| Public-Private | 26 | 14.21% | |

| Area | Technology, Digital Media, or Telecommunications | 67 | 36.61% |

| Engineering or Architecture | 44 | 24.04% | |

| Education | 20 | 10.93% | |

| Healthcare | 12 | 6.56% | |

| Administrative (Accounting, Finance, HR) | 8 | 4.37% | |

| Commercial (Sales, Marketing, Corporate Communication) | 8 | 4.37% | |

| Others | 24 | 13.11% | |

| Variables | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time working on projects with a on-site team environment | Not at this moment | 15 | 55.56% |

| For 1 years or less | 2 | 7.41% | |

| For 5 years or less | 3 | 11.11% | |

| For 10 years or less | 1 | 3.70% | |

| For More than 10 years | 6 | 22.22% | |

| Type of participation/role in the project | Leader or Project Manager | 11 | 40.74% |

| Team Member | 12 | 44.44% | |

| Others | 4 | 14.81% | |

| Personal location during the project | Southeast Region | 16 | 59.26% |

| International | 5 | 18.52% | |

| Northeast or South Regions | 4 | 14.81% | |

| Others | 2 | 7.41% | |

| Localização dos integrantes durante o projeto | Southeast Region | 16 | 59.26% |

| International | 5 | 18.52% | |

| Northeast Region | 3 | 11.11% | |

| Others | 3 | 11.11% | |

| Team Size | Up to 10 members | 14 | 51.85% |

| 11 to 50 members | 8 | 29.63% | |

| 51 to 100 members | 2 | 7.41% | |

| 101 to 500 members | 3 | 11.11% | |

| Organization Size | Up to 10 members | 10 | 37.04% |

| 11 to 50 members | 4 | 14.81% | |

| 51 to 100 members | 4 | 14.81% | |

| 101 to 500 members | 4 | 14.81% | |

| 501 to 1000 members | 2 | 7.41% | |

| 1001 or more people | 3 | 11.11% | |

| Project Budget | Up to R$100,000 | 6 | 22.22% |

| R$101,000 to R$500,000 | 3 | 11.11% | |

| R$501,000 to R$1,000,000 | 5 | 18.52% | |

| R$1,000,001 to R$500,000,000 | 8 | 29.63% | |

| R$500,000,001 to R$1 billion | 1 | 3.70% | |

| Above R$1 billion | 4 | 14.81% | |

| Sector | Private | 16 | 59.26% |

| Public | 8 | 29.63% | |

| Public-Private | 3 | 11.11% | |

| Project Area | Engineering or Architecture | 11 | 40.74% |

| Technology, Digital Media, or Telecommunications | 3 | 11.11% | |

| Education | 2 | 7.41% | |

| Others | 11 | 40.74% | |

Appendix C

| Construct | Item | Mean | S.D. | C.I. 95% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Teams (VT) | Cultural Intelligence (CI) | 5.1.1 | 3.28 | 1.03 | [3.13: 3.42] | |

| 5.1.2 | 3.83 | 0.91 | [3.70: 3.96] | |||

| 5.1.3 | 3.56 | 0.92 | [3.42: 3.70] | |||

| 5.1.4 | 3.57 | 0.92 | [3.43: 3.69] | |||

| 5.1.5 | 4.26 | 0.66 | [4.17: 4.35] | |||

| 5.1.6 | 4.32 | 0.71 | [4.22: 4.43] | |||

| 5.1.7 | 4.18 | 0.63 | [4.09: 4.27] | |||

| 5.1.8 | 4.02 | 0.83 | [3.90: 4.13] | |||

| 5.1.9 | 4.51 | 0.65 | [4.42: 4.61] | |||

| 5.1.10 | 4.10 | 0.88 | [3.96: 4.23] | |||

| 5.1.11 | 4.06 | 0.81 | [3.95: 4.17] | |||

| 5.1.12 | 3.57 | 1.04 | [3.43: 3.72] | |||

| 5.1.13 | 3.83 | 0.89 | [3.70: 3.96] | |||

| 5.1.14 | 3.62 | 1.10 | [3.46: 3.79] | |||

| 5.1.15 | 3.84 | 0.86 | [3.72: 3.95] | |||

| 5.1.16 | 4.10 | 0.75 | [4.00: 4.22] | |||

| 5.1.17 | 3.95 | 0.90 | [3.83: 4.08] | |||

| 5.1.18 | 3.62 | 1.01 | [3.47: 3.77] | |||

| Communication Accommodation (CA) | 5.2.1 | 4.08 | 0.67 | [3.98: 4.17] | ||

| 5.2.2 | 4.40 | 0.56 | [4.32: 4.48] | |||

| 5.2.3 | 4.20 | 0.72 | [4.09: 4.30] | |||

| 5.2.4 | 4.30 | 0.65 | [4.20: 4.38] | |||

| 5.2.5 | 4.32 | 0.64 | [4.23: 4.41] | |||

| 5.2.6 | 4.16 | 0.71 | [4.06: 4.26] | |||

| 5.2.7 | 4.42 | 0.64 | [4.32: 4.50] | |||

| Team Sinergy (TS) | 5.3.1 | 3.58 | 0.96 | [3.43: 3.71] | ||

| 5.3.2 | 3.58 | 0.88 | [3.45: 3.71] | |||

| 5.3.3 | 3.62 | 0.89 | [3.49: 3.74] | |||

| 5.3.4 | 3.34 | 0.96 | [3.20: 3.47] | |||

| 5.3.5 | 3.86 | 0.79 | [3.75: 3.98] | |||

| 5.3.6 | 4.02 | 0.77 | [3.90: 4.13] | |||

| 5.3.7 | 3.72 | 0.86 | [3.58: 3.85] | |||

| 5.3.8 | 3.95 | 0.81 | [3.84: 4.07] | |||

| 5.3.9 | 3.52 | 1.05 | [3.37: 3.68] | |||

| Team Direction (TD) | 5.4.1 | 3.43 | 0.92 | [3.29: 3.55] | ||

| 5.4.2 | 3.68 | 0.82 | [3.56: 3.79] | |||

| 5.4.3 | 3.70 | 0.86 | [3.58: 3.83] | |||

| 5.4.4 | 3.56 | 1.02 | [3.42: 3.70] | |||

| 5.4.5 | 3.72 | 0.90 | [3.58: 3.85] | |||

| 5.4.6 | 3.73 | 0.85 | [3.61: 3.85] | |||

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) | 5.5.1 | 3.61 | 1.06 | [3.46: 3.75] | ||

| 5.5.2 | 3.56 | 1.02 | [3.40: 3.71] | |||

| 5.5.3 | 3.52 | 1.03 | [3.37: 3.67] | |||

| 5.5.4 | 3.62 | 1.03 | [3.47: 3.78] | |||

| 5.5.5 | 3.29 | 1.20 | [3.10: 3.46] | |||

| 5.5.6 | 3.39 | 1.16 | [3.22: 3.55] | |||

| Environment and Resources (ER) | 5.6.1 | 3.91 | 1.01 | [3.75: 4.05] | ||

| 5.6.2 | 3.75 | 1.07 | [3.59: 3.90] | |||

| 5.6.3 | 4.19 | 0.86 | [4.05: 4.30] | |||

| 5.6.4 | 3.99 | 0.93 | [3.85: 4.12] | |||

| 5.6.5 | 3.66 | 1.09 | [3.50: 3.81] | |||

| 5.6.6 | 3.66 | 1.09 | [3.50: 3.81] | |||

| Sustainability in Project Management (SPM) | Economic (EC) | 6.1.1 | 3.76 | 0.92 | [3.62: 3.88] | |

| 6.1.2 | 3.62 | 0.94 | [3.48: 3.75] | |||

| 6.1.3 | 3.83 | 0.98 | [3.69: 3.97] | |||

| 6.1.4 | 3.99 | 0.79 | [3.88: 4.09] | |||

| 6.1.5 | 3.85 | 0.83 | [3.73: 3.96] | |||

| 6.1.6 | 3.85 | 0.88 | [3.72: 3.98] | |||

| 6.1.7 | 3.79 | 0.88 | [3.66: 3.91] | |||

| 6.1.8 | 3.48 | 0.94 | [3.35: 3.61] | |||

| 6.1.9 | 3.73 | 0.90 | [3.59: 3.85] | |||

| 6.1.10 | 3.42 | 0.96 | [3.28: 3.56] | |||

| 6.1.11 | 3.83 | 0.95 | [3.69: 3.95] | |||

| 6.1.12 | 3.57 | 1.02 | [3.43: 3.72] | |||

| Environment (EN) | 6.2.1 | 3.37 | 1.03 | [3.22: 3.51] | ||

| 6.2.2 | 3.38 | 1.10 | [3.23: 3.54] | |||

| 6.2.3 | 3.24 | 1.13 | [3.07: 3.40] | |||

| 6.2.4 | 3.11 | 1.08 | [2.96: 3.26] | |||

| 6.2.5 | 3.25 | 1.08 | [3.09: 3.41] | |||

| 6.2.6 | 3.20 | 1.06 | [3.05: 3.35] | |||

| 6.2.7 | 3.20 | 1.06 | [3.04: 3.36] | |||

| 6.2.8 | 3.22 | 1.04 | [3.07: 3.37] | |||

| 6.2.9 | 3.20 | 1.04 | [3.05: 3.35] | |||

| 6.2.10 | 3.16 | 1.08 | [3.01: 3.31] | |||

| 6.2.11 | 3.08 | 1.05 | [2.93: 3.25] | |||

| Social (SO) | 6.3.1 | 3.92 | 0.97 | [3.78: 4.05] | ||

| 6.3.2 | 3.81 | 0.99 | [3.67: 3.97] | |||

| 6.3.3 | 3.48 | 1.05 | [3.32: 3.63] | |||

| 6.3.4 | 3.95 | 0.84 | [3.83: 4.08] | |||

| 6.3.5 | 3.20 | 1.09 | [3.03: 3.36] | |||

| 6.3.6 | 3.86 | 1.07 | [3.70: 4.01] | |||

| 6.3.7 | 3.48 | 1.11 | [3.34: 3.65] | |||

| 6.3.8 | 3.92 | 0.86 | [3.80: 4.05] | |||

| 6.3.9 | 3.34 | 1.10 | [3.19: 3.51] | |||

| 6.3.10 | 3.83 | 0.97 | [3.69: 3.97] | |||

| 6.3.11 | 3.52 | 1.03 | [3.37: 3.66] | |||

| 6.3.12 | 3.68 | 1.07 | [3.52: 3.83] | |||

| 6.3.13 | 3.24 | 1.01 | [3.09: 3.39] | |||

| Stakeholder Engagement (SE) | 7.1 | 4.14 | 0.94 | [3.99: 4.27] | ||

| 7.2 | 3.98 | 0.95 | [3.85: 4.13] | |||

| 7.3 | 4.15 | 0.89 | [4.02: 4.27] | |||

| 7.4 | 3.95 | 0.91 | [3.81: 4.08] | |||

| 7.5 | 3.83 | 1.00 | [3.69: 3.97] | |||

| 7.6 | 3.96 | 0.92 | [3.82: 4.08] | |||

| 7.7 | 3.96 | 0.97 | [3.80: 4.11] | |||

| 7.8 | 4.02 | 0.91 | [3.90: 4.15] | |||

| 7.9 | 3.74 | 0.96 | [3.61: 3.88] | |||

| 7.10 | 3.72 | 0.98 | [3.57: 3.85] | |||

| Knowledge Management (KM) | Organization/ Methodology (OM) | Centralization (CE) | 8.1.1.1 | 3.23 | 1.12 | [3.07: 3.38] |

| 8.1.1.2 | 3.33 | 1.08 | [3.17: 3.49] | |||

| 8.1.1.3 | 2.87 | 1.00 | [2.72: 3.01] | |||

| 8.1.1.4 | 2.95 | 1.06 | [2.81: 3.11] | |||

| 8.1.1.5 | 2.79 | 1.17 | [2.62: 2.96] | |||

| Centralization (FO) | 8.1.2.1 | 3.43 | 1.14 | [3.27: 3.59] | ||

| 8.1.2.2 | 3.16 | 1.02 | [3.01: 3.33] | |||

| 8.1.2.3 | 3.33 | 1.13 | [3.17: 3.50] | |||

| Training (TR) | 8.1.3.1 | 3.56 | 0.99 | [3.42: 3.70] | ||

| 8.1.3.2 | 3.55 | 1.10 | [3.40: 3.72] | |||

| 8.1.3.3 | 3.49 | 1.11 | [3.33: 3.65] | |||

| 8.1.3.4 | 3.07 | 1.14 | [2.91: 3.22] | |||

| 8.1.3.5 | 3.32 | 1.14 | [3.14: 3.48] | |||

| 8.1.3.6 | 3.22 | 1.18 | [3.05: 3.38] | |||

| Performance measurement (PM) | 8.1.4.1 | 2.98 | 1.13 | [2.83: 3.14] | ||

| 8.1.4.2 | 2.74 | 1.12 | [2.58: 2.90] | |||

| 8.1.4.3 | 2.87 | 1.16 | [2.70: 3.04] | |||

| 8.1.4.4 | 2.91 | 1.15 | [2.74: 3.08] | |||

| 8.1.4.5 | 3.16 | 1.16 | [2.99: 3.32] | |||

| 8.1.4.6 | 3.16 | 1.11 | [2.99: 3.32] | |||

| 8.1.4.7 | 3.49 | 1.00 | [3.34: 3.63] | |||

| 8.1.4.8 | 3.29 | 1.08 | [3.13: 3.44] | |||

| Benchmarking (BM) | 8.1.5.1 | 3.62 | 1.06 | [3.48: 3.76] | ||

| 8.1.5.2 | 3.83 | 0.96 | [3.69: 3.97] | |||

| 8.1.5.3 | 3.63 | 1.07 | [3.46: 3.78] | |||

| 8.1.5.4 | 3.86 | 0.93 | [3.73: 3.99] | |||

| 8.1.5.5 | 3.74 | 0.98 | [3.60: 3.88] | |||

| 8.1.5.6 | 3.45 | 1.08 | [3.29: 3.60] | |||

| 8.1.5.7 | 3.74 | 0.97 | [3.60: 3.87] | |||

| 8.1.5.8 | 3.50 | 1.17 | [3.33: 3.67] | |||

| ICT Systems (ICT) | 8.2.1 | 3.67 | 1.16 | [3.48: 3.83] | ||

| 8.2.2 | 3.97 | 0.99 | [3.84: 4.11] | |||

| 8.2.3 | 3.83 | 1.02 | [3.68: 3.97] | |||

| 8.2.4 | 3.49 | 1.10 | [3.33: 3.64] | |||

| 8.2.5 | 3.99 | 0.96 | [3.86: 4.13] | |||

| Human Aspects (HA) | Culture: Trust (CT) | 8.3.1.1 | 4.02 | 0.85 | [3.90: 4.14] | |

| 8.3.1.2 | 3.96 | 0.82 | [3.84: 4.07] | |||

| 8.3.1.3 | 3.98 | 0.79 | [3.88: 4.09] | |||

| 8.3.1.4 | 4.08 | 0.73 | [3.98: 4.19] | |||

| 8.3.1.5 | 3.95 | 0.83 | [3.82: 4.06] | |||

| 8.3.1.6 | 3.91 | 0.87 | [3.78: 4.03] | |||

| Culture: Collaboration (CC) | 8.3.2.1 | 3.58 | 0.84 | [3.47: 3.70] | ||

| 8.3.2.2 | 3.98 | 0.77 | [3.87: 4.10] | |||

| 8.3.2.3 | 3.98 | 0.84 | [3.86: 4.09] | |||

| 8.3.2.4 | 3.66 | 0.99 | [3.51: 3.79] | |||

| 8.3.2.5 | 3.28 | 1.07 | [3.13: 3.43] | |||

| 8.3.2.6 | 3.38 | 1.22 | [3.20: 3.54] | |||

| Culture: Learning (CL) | 8.3.3.1 | 3.22 | 1.14 | [3.05: 3.38] | ||

| 8.3.3.2 | 3.50 | 1.20 | [3.34: 3.68] | |||

| 8.3.3.3 | 3.17 | 1.17 | [3.01: 3.34] | |||

| 8.3.3.4 | 3.30 | 1.07 | [3.14: 3.45] | |||

| 8.3.3.5 | 3.21 | 1.09 | [3.05: 3.37] | |||

| Culture: Rewards/Incentives (CI) | 8.3.4.1 | 2.87 | 1.16 | [2.69: 3.05] | ||

| 8.3.4.2 | 3.49 | 1.20 | [3.31: 3.66] | |||

| 8.3.4.3 | 2.93 | 1.11 | [2.77: 3.09] | |||

| 8.3.4.4 | 2.76 | 1.07 | [2.61: 2.91] | |||

| 8.3.4.5 | 3.43 | 1.11 | [3.27: 3.58] | |||

| 8.3.4.6 | 3.78 | 1.03 | [3.63: 3.92] | |||

| Transformational Leadership (TL) | 8.3.5.1 | 3.79 | 0.94 | [3.66: 3.92] | ||

| 8.3.5.2 | 3.76 | 1.01 | [3.61: 3.90] | |||

| 8.3.5.3 | 3.69 | 1.05 | [3.54: 3.84] | |||

| 8.3.5.4 | 3.72 | 1.03 | [3.57: 3.86] | |||

| 8.3.5.5 | 3.47 | 1.12 | [3.30: 3.63] | |||

| 8.3.5.6 | 3.14 | 1.17 | [2.98: 3.30] | |||

| 8.3.5.7 | 3.67 | 0.97 | [3.52: 3.80] | |||

| 8.3.5.8 | 2.76 | 1.25 | [2.59: 2.95] | |||

| Teamwork (TW) | 8.3.6.1 | 4.01 | 0.86 | [3.89: 4.13] | ||

| 8.3.6.2 | 4.02 | 0.82 | [3.89: 4.12] | |||

| 8.3.6.3 | 4.05 | 0.77 | [3.94: 4.16] | |||

| 8.3.6.4 | 3.89 | 0.78 | [3.78: 4.00] | |||

| 8.3.6.5 | 4.10 | 0.72 | [4.00: 4.20] | |||

| 8.3.6.6 | 4.34 | 0.69 | [4.24: 4.43] | |||

| Project Success (PS) | Future Potential (FP) | 9.1.1 | 4.22 | 0.72 | [4.11: 4.32] | |

| 9.1.2 | 3.96 | 0.89 | [3.82: 4.08] | |||

| 9.1.3 | 4.04 | 0.80 | [3.93: 4.17] | |||

| 9.1.4 | 4.14 | 0.81 | [4.02: 4.26] | |||

| Organizational Benefits (OB) | 9.2.1 | 3.93 | 0.83 | [3.83: 4.05] | ||

| 9.2.2 | 4.31 | 0.65 | [4.22: 4.40] | |||

| 9.2.3 | 4.31 | 0.68 | [4.20: 4.41] | |||

| 9.2.4 | 4.16 | 0.78 | [4.04: 4.27] | |||

| 9.2.5 | 4.23 | 0.77 | [4.11: 4.33] | |||

| Project Efficiency (PE) | 9.3.1 | 3.64 | 1.07 | [3.49: 3.79] | ||

| 9.3.2 | 4.05 | 0.84 | [3.93: 4.17] | |||

| 9.3.3 | 4.09 | 0.81 | [3.97: 4.19] | |||

| 9.3.4 | 3.13 | 1.17 | [2.95: 3.31] | |||

| 9.3.5 | 3.65 | 1.23 | [3.48: 3.81] | |||

| 9.3.6 | 3.96 | 0.89 | [3.84: 4.09] | |||

| 9.3.7 | 3.66 | 1.07 | [3.51: 3.81] | |||

| 9.3.8 | 3.84 | 0.99 | [3.70: 3.97] | |||

| Project Impact (PI) | 9.4.1 | 4.19 | 0.73 | [4.08: 4.28] | ||

| 9.4.2 | 4.29 | 0.69 | [4.20: 4.39] | |||

| 9.4.3 | 4.17 | 0.76 | [4.06: 4.28] | |||

| 9.4.4 | 4.29 | 0.70 | [4.20: 4.39] | |||

| Stakeholder Satisfaction (SS) | 9.5.1 | 4.19 | 0.76 | [4.07: 4.30] | ||

| 9.5.2 | 4.17 | 0.75 | [4.07: 4.27] | |||

| 9.5.3 | 4.15 | 0.78 | [4.04: 4.26] | |||

| 9.5.4 | 4.23 | 0.75 | [4.12: 4.35] | |||

Appendix D

| Construct | Item | F.L. 1 | Com. 2 | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Management (KM) × Virtual Teams (VT) | Cultural Intelligence (CI) × OM | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.07 |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × OM | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.08 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × OM | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.07 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × OM | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.08 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × OM | 0.56 | 0.31 | 0.03 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × OM | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.08 | |

| Cultural Intelligence (CI) × ICT | 0.76 | 0.58 | 0.07 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × ICT | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.07 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × ICT | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.07 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × ICT | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.08 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × ICT | 0.54 | 0.30 | 0.04 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × ICT | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.08 | |

| Cultural Intelligence (CI) × HA | 0.80 | 0.64 | 0.08 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × HA | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.09 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × HA | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.07 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × HA | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.09 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × HA | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.03 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × HA | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.09 | |

| Stakeholder Engagement (SE) × Virtual Teams (VT) | Cultural Intelligence (CI) × 7.1 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.03 |

| Cultural Intelligence (CI) × 7.2 | 0.79 | 0.62 | 0.03 | |

| Cultural Intelligence (CI) × 7.3 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.02 | |

| Cultural Intelligence (CI) × 7.4 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.02 | |

| Cultural Intelligence (CI) × 7.5 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.02 | |

| Cultural Intelligence (CI) × 7.6 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.02 | |

| Cultural Intelligence (CI) × 7.7 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.02 | |

| Cultural Intelligence (CI) × 7.8 | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.02 | |

| Cultural Intelligence (CI) × 7.9 | 0.78 | 0.60 | 0.02 | |

| Cultural Intelligence (CI) × 7.10 | 0.66 | 0.43 | 0.02 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × 7.1 | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.03 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × 7.2 | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.03 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × 7.3 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.03 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × 7.4 | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.02 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × 7.5 | 0.74 | 0.54 | 0.02 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × 7.6 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.02 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × 7.7 | 0.79 | 0.62 | 0.02 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × 7.8 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 0.02 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × 7.9 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.02 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × 7.10 | 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.02 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × 7.1 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 0.03 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × 7.2 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.03 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × 7.3 | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.02 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × 7.4 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.02 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × 7.5 | 0.73 | 0.54 | 0.02 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × 7.6 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.02 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × 7.7 | 0.80 | 0.64 | 0.02 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × 7.8 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.02 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × 7.9 | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.02 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × 7.10 | 0.69 | 0.47 | 0.02 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × 7.1 | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.03 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × 7.2 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.03 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × 7.3 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.03 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × 7.4 | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.02 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × 7.5 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.02 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × 7.6 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.02 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × 7.7 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.02 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × 7.8 | 0.79 | 0.62 | 0.02 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × 7.9 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.02 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × 7.10 | 0.73 | 0.54 | 0.03 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × 7.1 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.01 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × 7.2 | 0.59 | 0.35 | 0.01 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × 7.3 | 0.59 | 0.35 | 0.01 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × 7.4 | 0.59 | 0.35 | 0.01 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × 7.5 | 0.52 | 0.27 | 0.01 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × 7.6 | 0.59 | 0.35 | 0.01 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × 7.7 | 0.58 | 0.33 | 0.01 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × 7.8 | 0.55 | 0.30 | 0.01 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × 7.9 | 0.61 | 0.37 | 0.01 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × 7.10 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.01 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × 7.1 | 0.69 | 0.47 | 0.03 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × 7.2 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.03 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × 7.3 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.03 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × 7.4 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.02 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × 7.5 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.02 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × 7.6 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.02 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × 7.7.5 | 0.74 | 0.54 | 0.02 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × 7.8 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.02 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × 7.9 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.02 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × 7.10 | 0.64 | 0.42 | 0.03 | |

| Sustainability in Project Management (SPM) × Virtual Teams (VT) | Cultural Intelligence (CI) × EC | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.08 |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × EC | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.08 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × EC | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.08 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × EC | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.09 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × EC | 0.66 | 0.44 | 0.03 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × EC | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.08 | |

| Cultural Intelligence (CI) × EN | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.04 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × EN | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.04 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × EN | 0.77 | 0.60 | 0.05 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × EN | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.06 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × EN | 0.66 | 0.44 | 0.01 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × EN | 0.76 | 0.59 | 0.05 | |

| Cultural Intelligence (CI) × SO | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.09 | |

| Communication Accommodation (CA) × SO | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.10 | |

| Team Sinergy (TS) × SO | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.10 | |

| Team Direction (TD) × SO | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.10 | |

| Multi-Regional Virtual Team (MR) × SO | 0.66 | 0.44 | 0.04 | |

| Environment and Resources (ER) × SO | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.10 | |

| Knowledge Management (KM) | Organization/Methodology (OM) | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.42 |

| ICT Systems (ICT) | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.31 | |

| Human Aspects (HA) | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.43 | |

| Stakeholder Engagement (SE) | 7.1.6 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.13 |

| 7.2.6 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.13 | |

| 7.3.6 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.13 | |

| 7.4.6 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.13 | |

| 7.5.6 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 0.12 | |

| 7.6.6 | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.14 | |

| 7.7.6 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.13 | |

| 7.8.6 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.11 | |

| 7.9.6 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.13 | |

| 7.10.6 | 0.66 | 0.43 | 0.16 | |

| Sustainability in Project Management (SPM) | Economic (EC) | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.41 |

| Environment (EN) | 0.71 | 0.51 | 0.20 | |

| Social (SO) | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.55 | |

| Project Success (PS) | Future Potential (FP) | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.24 |

| Organizational Benefits (OB) | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.27 | |

| Project Efficiency (PE) | 0.82 | 0.66 | 0.27 | |

| Project Impact (PI) | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.23 | |

| Stakeholder Satisfaction (SS) | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.21 |

References

- Castro, M.S.; Bahli, B.; Barcaui, A.; Figueiredo, R. Does One Project Success Measure Fit All? An Empirical Investigation of Brazilian Projects. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2021, 14, 788–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.; Balve, P.; Spang, K. Evaluation of Project Success: A Structured Literature Review. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2017, 10, 796–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.N.; Murphy, D.C.; Fisher, D. Factors Affecting Project Success. In Project Management Handbook; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 902–919. ISBN 9780470172353. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar, G.P. What Is Project Success: A Literature Review. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2008, 3, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belassi, W.; Tukel, O.I. A New Framework for Determining Critical Success/Failure Factors in Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1996, 14, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heravi, A.; Coffey, V.; Trigunarsyah, B. Evaluating the Level of Stakeholder Involvement during the Project Planning Processes of Building Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, J.; Larsson, L. Integration, Application and Importance of Collaboration in Sustainable Project Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.S.; Bahli, B.; Farias Filho, J.R.; Barcaui, A. A Contemporary Vision of Project Success Criteria. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2019, 16, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrchota, J.; Řehoř, P.; Maříková, M.; Pech, M. Critical Success Factors of the Project Management in Relation to Industry 4.0 for Sustainability of Projects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert Silvius, A.J.; Schipper, R. Exploring the Relationship between Sustainability and Project Success–Conceptual Model and Expected Relationships. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Proj. Manag. 2016, 4, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert Silvius, A.J.; Schipper, R.P.J. Sustainability in Project Management: A Literature Review and Impact Analysis. Soc. Bus. 2016, 4, 63–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, M.L.; Carvalho, M.M. The Challenge of Introducing Sustainability into Project Management Function: Multiple-Case Studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 117, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, G. Sustainability as a New School of Thought in Project Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 1479–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xue, B.; Meng, J.; Chen, X.; Sun, T. How Project Management Practices Lead to Infrastructure Sustainable Success: An Empirical Study Based on Goal-Setting Theory. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 2797–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; Lai, Y.; Li, L. Factors Influencing Collaborative Innovation Project Performance: The Case of China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.; Javed, B.; Mubarak, N.; Bashir, S.; Jaafar, M. Psychological Empowerment and Project Success: The Role of Knowledge Sharing. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 69, 2997–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, B.H.; Gemino, A.; Sauer, C. How Knowledge Management Impacts Performance in Projects: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, G.B.; Qualharini, E.L.; Castro, M.S. Enhancing Sustainability in Project Management: The Role of Stakeholder Engagement and Knowledge Management in Virtual Team Environments. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrascu-Băldău, I.; Dumitrascu, D.D.; Dobrota, G. Predictive Model for the Factors Influencing International Project Success: A Data Mining Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presbitero, A. Communication Accommodation within Global Virtual Team: The Influence of Cultural Intelligence and the Impact on Interpersonal Process Effectiveness. J. Int. Manag. 2021, 27, 100809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, J.; Smart, M.J. Working at Home and Elsewhere: Daily Work Location, Telework, and Travel among United States Knowledge Workers; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 48, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Blak Bernat, G.; Qualharini, E.L.; Castro, M.S.; Dias, M. Sustainability in project management and project success with teams in virtual environment. Int. J. Dev. Res. 2022, 12, 61024–61031. [Google Scholar]

- Swart, K.; Bond-Barnard, T.; Chugh, R. Challenges and Critical Success Factors of Digital Communication, Collaboration and Knowledge Sharing in Project Management Virtual Teams: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Proj. Manag. 2022, 10, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, A.K.; Bjeirmi, B.F. The Role of Project Management in Achieving Project Success. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1996, 14, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ika, L.A. Project Success as a Topic in Project Management Journals: A Brief History. Proj. Manag. J. 2009, 40, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannerman, P.L. Defining Project Success: A Multilevel Framework. In Proceedings of the PMI® Research Conference: Defining the Future of Project Management, Newtown Square, PA, USA, 16 July 2008; Project Management Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith, J.; Zwikael, O. When Is a Project Successful? IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2019, 47, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, A. Measurement of Project Success. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1988, 6, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, L.; Pollack, J. Hard and Soft Projects: A Framework for Analysis. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2004, 22, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarini, D. Defining Project Success Baccarini1999. Proj. Manag. J. 1997, 30, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.M.; Rabechini, R. Can Project Sustainability Management Impact Project Success? An Empirical Study Applying a Contingent Approach. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1120–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, G.P. Understanding the Meaning of “Project Success”. Binus Bus. Rev. 2016, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenhar, A.J.; Dvir, D. Reinventing Project Management: The Diamond Approach to Successful Growth and Innovation; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 9781591398004. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks–Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; New Society Publishers: Stoney Creek, CT, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Armenia, S.; Dangelico, R.M.; Nonino, F.; Pompei, A. Sustainable Project Management: A Conceptualization-Oriented Review and a Framework Proposal for Future Studies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, M.L.; Carvalho, M.M. Sustainability and Success Variables in the Project Management Context: An Expert Panel. Proj. Manag. J. 2016, 47, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.R.; Chen, J.H.; Lee, C.H. Exploring the Links between Task-Level Knowledge Management and Project Success. J. Test. Eval. 2017, 46, 1220–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, A.; Boehe, D.M.; Taras, V.; Caprar, D.V. Working Across Boundaries: Current and Future Perspectives on Global Virtual Teams. J. Int. Manag. 2017, 23, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg, R.M.; Bosch-Sijtsema, P.; Vartiainen, M. Getting It Done: Critical Success Factors for Project Managers in Virtual Work Settings. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G. Our Common Future: The World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Keeble, B.R. The Brundtland Report: “Our Common Future”. Med. War 1988, 4, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovers, S.R. Sustainability in Context: An Australian Perspective. Environ. Manag. 1990, 14, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labuschagne, C.; Brent, A.C. Sustainable Project Life Cycle Management: The Need to Integrate Life Cycles in the Manufacturing Sector. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2005, 23, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelino-Sádaba, S.; González-Jaen, L.F.; Pérez-Ezcurdia, A. Using Project Management as a Way to Sustainability. from a Comprehensive Review to a Framework Definition. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 99, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedknegt, D.; Silvius, G. The Implementation of Sustainability Principles in Project Management. In Proceedings of the 26th IPMA World Congress, Creta, Greece, 29–31 October 2012; pp. 875–882. [Google Scholar]

- Silvius, G.; Schipper, R. Schipper Planning Project Stakeholder Engagement from a Sustainable Development Perspective. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadia, L.G.; Carvalho, M.M. de Sustentabilidade Na Literatura de Gestão de Projetos: Temas Centrais, Tendências e Lacunas. Em Revisão 2017, 13, 52–75. [Google Scholar]

- Toljaga-Nikolić, D.; Todorović, M.; Dobrota, M.; Obradović, T.; Obradović, V. Project Management and Sustainability: Playing Trick or Treat with the Planet. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chofreh, A.G.; Goni, F.A.; Malik, M.N.; Khan, H.H.; Klemeš, J.J. The Imperative and Research Directions of Sustainable Project Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifeh, A.; Farrell, P.; Al-edenat, M. The Impact of Project Sustainability Management (PSM) on Project Success: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Manag. Dev. 2020, 39, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Martinsuo, M.; Blomquist, T. Project Portfolio Control and Portfolio Management Performance in Different Contexts. Proj. Manag. J. 2008, 39, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, I.; Huang, J. The Relationships between Key Stakeholders’ Project Performance and Project Success: Perceptions of Chinese Construction Supervising Engineers. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2006, 24, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, B.; Parkin, J. Planning Cycling Networks: Human Factors and Design Processes. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Eng. Sustain. 2011, 164, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascetta, E.; Cartenì, A.; Pagliara, F.; Montanino, M. A New Look at Planning and Designing Transportation Systems: A Decision-Making Model Based on Cognitive Rationality, Stakeholder Engagement and Quantitative Methods. Transp. Policy 2015, 38, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.S.; Mohamed, S.; Panuwatwanich, K. Stakeholder Management in Complex Project: Review of Contemporary Literature. J. Eng. Proj. Prod. Manag. 2018, 8, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.; Zolin, R. Forecasting Success on Large Projects: Developing Reliable Scales to Predict Multiple Perspectives by Multiple Stakeholders over Multiple Time Frames. Proj. Manag. J. 2012, 43, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaisi, I.F. The Effects of Stakeholder’s Engagement and Communication Management on Projects Success. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 162, 02037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariq, S.Z. Knowledge Management: An Emerging Discipline. J. Knowl. Manag. 1997, 1, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, P.S.W. Knowledge Creation in Multidisciplinary Project Teams: An Empirical Study of the Processes and Their Dynamic Interrelationships. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasvi, J.J.J.; Vartiainen, M.; Hailikari, M. Managing Knowledge and Knowledge Competences in Projects and Project Organisations. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluikpe, P.I. Knowledge Creation and Utilization in Project Teams. J. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 19, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995; ISBN 9780199879922. [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch, B.; Lindner, F.; Mueller, A.; Wald, A. Knowledge Management in Project Environments. J. Knowl. Manag. 2009, 13, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekera, V.S.; Chong, S.C. Knowledge Management Critical Success Factors and Project Management Performance Outcomes in Major Construction Organisations in Sri Lanka: A Case Study. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2018, 48, 537–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidavičienė, V.; Majzoub, K.A.; Meidute-Kavaliauskiene, I. Sustainability Factors A Ff Ecting Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Teams. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 7th ed.; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, G. Knowledge Management Success Equals Project Management Success. In Proceedings of the PMI® Global Congress 2010; PMI, Ed.; Project Management Institute: Washington, DC, USA; Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, K.F.; Afzal, O.; Saqib, A.; Sahibzada, U.F.; Alam, W. Direct and Configurational Paths of Knowledge-Oriented Leadership, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and Knowledge Management Processes to Project Success. J. Intellect. Cap. 2021, 22, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeong, A.; Lim, T.T. Integrating Knowledge Management with Project Management for Project Success. J. Proj. Progr. Portf. Manag. 2011, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskerod, P.; Huemann, M. Sustainable Development and Project Stakeholder Management: What Standards Say. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2013, 6, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Henriques, I. Stakeholder Influences on Sustainability Practices in the Canadian Forest Products Industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withisuphakorn, P.; Batra, I.; Parameswar, N.; Dhir, S. Sustainable Development in Practice: Case Study of L’Oréal. J. Bus. Retail Manag. Res. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 26000; Guidance on Social Responsibility. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 6–10. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, K.; Kim, Y.-W.; Kim, H. Stakeholder Management in Long-Term Complex Megaconstruction Projects: The Saemangeum Project. J. Manag. Eng. 2017, 33, 05017002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, D.F.; Ortiz-Marcos, I.; Uruburu, Á. What Is Going on with Stakeholder Theory in Project Management Literature? A Symbiotic Relationship for Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaegbuna, O.; Tasmiyah, C.; Zanoxolo, B.; Nikiwe, M. Sustainability in Project Management Practice. MATEC Web Conf. 2020, 312, 02015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudoba, K.M.; Wynn, E.; Lu, M.; Watson-Manheim, M.B. How Virtual Are We? Measuring Virtuality and Understanding Its Impact in a Global Organization. Inf. Syst. J. 2005, 15, 279–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iulia, D.-B.; Dumitru, D.D. Skills and Competences International Project Managers Need in Order to Be Successful in a Virtual Work Environment. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Brasov. Ser. V Econ. Sci. 2018, 10, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gubbi, J.; Buyya, R.; Marusic, S.; Palaniswami, M. Internet of Things (IoT): A Vision, Architectural Elements, and Future Directions. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2013, 29, 1645–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.D.; Eppinger, S.D.; Gulati, R.K. Predicting Technical Communication in Product Development Organizations. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1995, 42, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Tiwana, A. Knowledge Integration in Virtual Teams: The Potential Role of KMS. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2002, 53, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, S.; Mann, P. Interdisciplinarity: Perceptions of the Value of Computer-Supported Collaborative Work in Design for the Built Environment. Autom. Constr. 2003, 12, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPMA. Individual Competence Baseline for Project, Programme & Portfolio Management; IPMA: Zurich, Swirzerland, 2016; Volume 4, ISBN 9789492338013. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, R.X.; Carvalho, M.M.; Sbragia, R. Towards a Comprehensive Conceptual Framework for Multicultural Virtual Teams: A Multilevel Perspective Exploring the Relationship between Multiculturalism and Performance. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2022, 16, 325–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C.; Sivatheerthan, T.; Mütze-Niewöhner, S.; Nitsch, V. Sharing Leadership Behaviors in Virtual Teams: Effects of Shared Leadership Behaviors on Team Member Satisfaction and Productivity. Team Perform. Manag. 2023, 29, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekry Youssef, M.; Fathy Eid, A.; Mohamed Khodeir, L. Challenges Affecting Efficient Management of Virtual Teams in Construction in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookhamer, P.; Zhang, Z.J. Knowledge Management in a Global Context: A Case Study. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 2016, 29, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Toyama, R.; Konno, N. SECI, Ba and Leadership: A Unified Model of Dynamic Knowledge Creation. Long Range Plan. 2000, 33, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, M. A Correlational Study on Project Management Methodology and Project Success. J. Eng. Proj. Prod. Manag. 2019, 9, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Zafar, A.U.; Ding, X.; Rehman, S.U. Translating Stakeholders’ Pressure into Environmental Practices–The Mediating Role of Knowledge Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 124163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.A.; Li, Y.; Sistenich, V.; Diango, K.N.; Kabongo, D. A Multi-Stakeholder Engagement Framework for Knowledge Management in ICT4D. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molwus, J.J.; Erdogan, B.; Ogunlana, S. Using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) to Understand the Relationships among Critical Success Factors (CSFs) for Stakeholder Management in Construction. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2017, 24, 426–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.A.; Lewis, P. Research Methods for Business Students Eights Edition Research Methods for Business Students, 8th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 9781292208787. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.S.; Mohamed, S. Mediation Effect of Stakeholder Management between Stakeholder Characteristics and Project Performance. J. Eng. Proj. Prod. Manag. 2021, 11, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R.J. Introduction to the Bootstrap; Chapman & Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 0412042312. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, A.; Kateri, M. Categorical Data Analysis; John Wiley: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2011; Volume 45, ISBN 0471360937. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business researc. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingoti, S.A. Análise de Dados Através de Métodos de Estatística Multivariada: Uma Abordagem Aplicada; Editora UFMG: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vinzi, V.E.; Trinchera, L.; Amato, S. PLS Path Modeling: From Foundations to Recent Developments and Open Issues for Model Assessment and Improvement BT–Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Esposito Vinzi, V., Chin, W.W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 47–82. ISBN 978-3-540-32827-8. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Risco, A.; Mlodzianowska, S.; García-Ibarra, V.; Rosen, M.A.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S. Factors Affecting Green Entrepreneurship Intentions in Business University Students in COVID-19 Pandemic Times: Case of Ecuador. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, G. PLS Path Modeling with R. R Packag. Notes 2013, 235, 13341888. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In Advances in International Marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; New Challenges to International Marketing, Volume 20; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; McGraw-Hill Series in Psychology; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: Chennai, India, 1994; ISBN 9780071070881. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.; Marcoulides, G. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 8, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R.H.; Duvall, J.L. Determining the Number of Factors in Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis. In The Sage Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences; Kaplan, D., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Raîche, G.; Walls, T.; Magis, D.; Riopel, M.; Blais, J.-G. Non-Graphical Solutions for Cattell’s Scree Test. Methodology 2013, 9, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Amato, S.; Esposito Vinzi, V. A Global Goodness-of-Fit Index for PLS Structural Equation Modelling. Proc. XLII SIS Sci. Meet. 2004, 1, 739–742. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Sarstedt, M. Goodness-of-Fit Indices for Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. Comput. Stat. 2013, 28, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, M.L.; Carvalho, M.M. Key Factors of Sustainability in Project Management Context: A Survey Exploring the Project Managers’ Perspective. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1084–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanitsas, M.; Kirytopoulos, K.; Leopoulos, V. Integrating Sustainability Indicators into Project Management: The Case of Construction Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes Silva, F.J.; Kirytopoulos, K.; Pinto Ferreira, L.; Sá, J.C.; Santos, G.; Cancela Nogueira, M.C. The Three Pillars of Sustainability and Agile Project Management: How Do They Influence Each Other. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1495–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koke, B.; Moehler, R.C. Earned Green Value Management for Project Management: A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraigheeth, M.; Fadzli, S.A. Core Factors for Software Projects Success. Int. J. Informatics Vis. 2019, 3, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossum, K.R.; Binder, J.C.; Madsen, T.K.; Aarseth, W.; Andersen, B. Success Factors in Global Project Management: A Study of Practices in Organizational Support and the Effects on Cost and Schedule. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2020, 13, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hypothesis | Null | Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | SPM does not have a positive influence on PS | SPM has a positive influence on PS |

| H2 | SE does not have a positive influence on PS | SE has a positive influence on PS |

| H3 | KM does not have a positive influence on PS | KM has a positive influence on PS |

| H4 | SE does not have a positive influence on SPM | SE has a positive influence on SPM |

| H5 | KM does not have a positive influence on SPM | KM has a positive influence on SPM |

| H6 | VTs do not have a moderating effect on H1 | VTs have a moderating effect on H1 |

| H7 | VTs do not have a moderating effect on H2 | VTs have a moderating effect on H2 |

| H8 | VTs do not have a moderating effect on H3 | VTs have a moderating effect on H3 |

| H9 | SE and KM do not have a positive correlation | SE and KM have a positive correlation |

| Construct | Items | AVE. 1 | M.S.V. 2 | C.A. 3 | C.R. 4 | Dim. 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Management (KM) × Virtual Teams (VT) | 18 | 0.60 | 0.83 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 1 |

| Stakeholder Engagement (SE) × Virtual Teams (VT) | 60 | 0.54 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1 |

| Sustainability in Project Management (SPM) × Virtual Teams (VT) | 18 | 0.62 | 0.84 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 1 |

| Knowledge Management (KM) | 3 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.89 | 1 |

| Stakeholder Engagement (SE) | 10 | 0.60 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 1 |

| Sustainability in Project Management (SPM) | 3 | 0.69 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 1 |

| Project Success (PS) | 5 | 0.67 | 0.38 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 1 |

| Endogenous | Exogenous | β | S.E. (β) 1 | C.I. 95% 2 | p-Value | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability in Project Management (SPM) | Knowledge Management (KM) 3 | 0.27 | 0.07 | [0.12; 0.43] | <0.001 | 31.73% |

| Stakeholder Engagement (SE) 3 | 0.39 | 0.07 | [0.24; 0.53] | <0.001 | ||

| Project Success (PS) | KM × VT | 0.50 | 0.48 | [−0.73; 1.62] | 0.296 | 42.06% |

| SE × VT | 0.52 | 0.79 | [−1.70; 2.51] | 0.509 | ||

| SPM × VT | −0.60 | 0.66 | [−2.21; 1.16] | 0.358 | ||

| Knowledge Management (KM) 3 | 0.23 | 0.07 | [0.11; 0.37] | 0.001 | ||

| Stakeholder Engagement (SE) 3 | 0.41 | 0.07 | [0.26; 0.54] | <0.001 | ||

| Sustainability in Project Management (SPM) | 0.12 | 0.07 | [−0.03; 0.26] | 0.100 |

| Hypothesis | Description | Result |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | SPM has a positive influence on PS | Not confirmed |

| H2 | SE has a positive influence on PS | Confirmed |

| H3 | KM has a positive influence on PS | Confirmed |

| H4 | SE has a positive influence on SPM | Confirmed |

| H5 | KM has a positive influence on SPM | Confirmed |

| H6 | VT has a moderating effect on H1 (SPM × PS) | Not confirmed |

| H7 | VT has a moderating effect on H2 (SE × PS) | Not confirmed |

| H8 | VT has a moderating effect on H3 (KM × PS) | Not confirmed |

| H9 | SE and KM have a positive correlation | Confirmed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blak Bernat, G.; Qualharini, E.L.; Castro, M.S.; Barcaui, A.B.; Soares, R.R. Sustainability in Project Management and Project Success with Virtual Teams: A Quantitative Analysis Considering Stakeholder Engagement and Knowledge Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129834

Blak Bernat G, Qualharini EL, Castro MS, Barcaui AB, Soares RR. Sustainability in Project Management and Project Success with Virtual Teams: A Quantitative Analysis Considering Stakeholder Engagement and Knowledge Management. Sustainability. 2023; 15(12):9834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129834

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlak Bernat, Gisele, Eduardo Linhares Qualharini, Marcela Souto Castro, André Baptista Barcaui, and Raquel Reis Soares. 2023. "Sustainability in Project Management and Project Success with Virtual Teams: A Quantitative Analysis Considering Stakeholder Engagement and Knowledge Management" Sustainability 15, no. 12: 9834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129834

APA StyleBlak Bernat, G., Qualharini, E. L., Castro, M. S., Barcaui, A. B., & Soares, R. R. (2023). Sustainability in Project Management and Project Success with Virtual Teams: A Quantitative Analysis Considering Stakeholder Engagement and Knowledge Management. Sustainability, 15(12), 9834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129834