1. Introduction

The SME sector is commonly known as the driving force behind the economy, as it generates employment opportunities and plays a crucial role in global economic growth. The World Bank estimates that SMEs account for around 90% of firms and 70% of employment in OECD nations and contribute almost 50% of GDP in high-income countries worldwide and 40% of the GDP in emerging economies, and this figure increases further if informal SMEs are also considered [

1]. These facts look surprising given that research has been mostly focused on large companies. However, in recent years, the global economic climate has experienced a discernible alteration, tilting towards the most dynamic, flexible, and innovative human-sized businesses, resulting in a noticeable decline in large companies’ dominance. While the proper definition of these organizations may differ among experts and decision-makers, especially in emerging economies, their vital significance and crucial value are universally accepted. The question, therefore, becomes not why they should be promoted but how best to do it.

Indeed, compared to large companies, SMEs are more flexible but at the expense of less stable working conditions and lower wages. They are less productive, but they create many additional employment opportunities as a result of their broad growth potential. They are innovative, but their innovations are mostly incremental because radical innovations need considerable investment in R&D, as is characteristic of large companies. While working conditions in SMEs are typically more onerous, they create significant social relationships through their local activities, facilitating the natural resolution of knowledge transfer and sharing challenges [

2,

3,

4]. Therefore, managing SMEs requires a personalized approach that prioritizes their untapped potential to achieve optimal effectiveness and sustained success.

Such an approach must be based on strong knowledge management, combining techniques, procedures, and resources that allow creating, sharing, and applying the knowledge circulating within the SME while also ensuring the best use of information from outside to improve its performance [

5,

6]. A knowledge management logic might help the SME better understand and leverage this internal and external information and knowledge to achieve a competitive advantage and, hence, increase performance [

7].

The majority of knowledge management research focuses on large-scale companies, but this does not mean that SMEs cannot take advantage of it, as well. However, SME managers may face challenges when trying to adopt the same tools and logic used by larger companies. In SMEs, efficient knowledge management requires recognizing and valuing their unique organizational style, which can be achieved by considering various features that aid in knowledge generation, sharing, and exploitation [

8]. Such features include factors such as strong interpersonal relationships, a culture of collaboration, and a trustworthy climate.

Indeed, establishing a trustworthy environment is crucial for managing small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), as the relationships between members are similar to familial bonds. This sense of family can reduce the need for complicated formal procedures. Trust is a person’s feeling of security when relying on others to achieve a result. It plays a major role in producing knowledge and improving performance in SMEs [

8]. First of all, it is considered by some authors to be the most important factor for knowledge creation as it encourages trial-and-error learning and allows employees to freely voice their initial ideas. Secondly, trust also plays a crucial role in sharing knowledge in SMEs. Many authors consider trust as the most important precondition for knowledge exchange [

9]. Others confirm that trust plays a central role in knowledge sharing because it encourages team members to share their knowledge and creates emotional openness that supports listening and absorbing knowledge [

10]. Teams with a high level of trust are more open, share more information, are more creative, and offer better solutions [

11]. Exchanging this knowledge and ideas and sharing experiences and valuable information improve firm performance. Chou (2008) [

12] emphasized that organizational trust influences employees’ motivation to share knowledge within the organization to achieve its goals. Finally, trust plays a crucial role in applying knowledge in SMEs, as it facilitates the development of effective solutions. The degree to which an individual feels inclined to engage in the problems of others is heavily influenced by the connection between consideration and involvement in a workplace. A lack of trust may cause negative consequences for SMEs’ problem-solving efforts and performance. Many authors confirmed that when there is insufficient trust in the organization, concealing behavior manifests in the form of playing dumb (claiming to have no idea about the knowledge being requested), rationalized hiding (providing a rational reason for not sharing the knowledge being requested), and evasive hiding (providing misleading information or promising to share the requested knowledge in the future) [

13]. Holste and Fields (2010) [

14] confirmed that, without trust, social exchange and knowledge sharing would be challenged, which consequently leads to undesirable outcomes. That means when trust is high and spreads in SMEs, employees will care about the future and success of their organization; therefore, they act to improve organizational productivity, and vice versa.

Although there is an abundance of research on the role of trust in knowledge management and performance in large companies that benefit from numerous empirical validations, they appear to overlook a crucial aspect: whether trust moderates the impact of KM on firm performance in the context of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

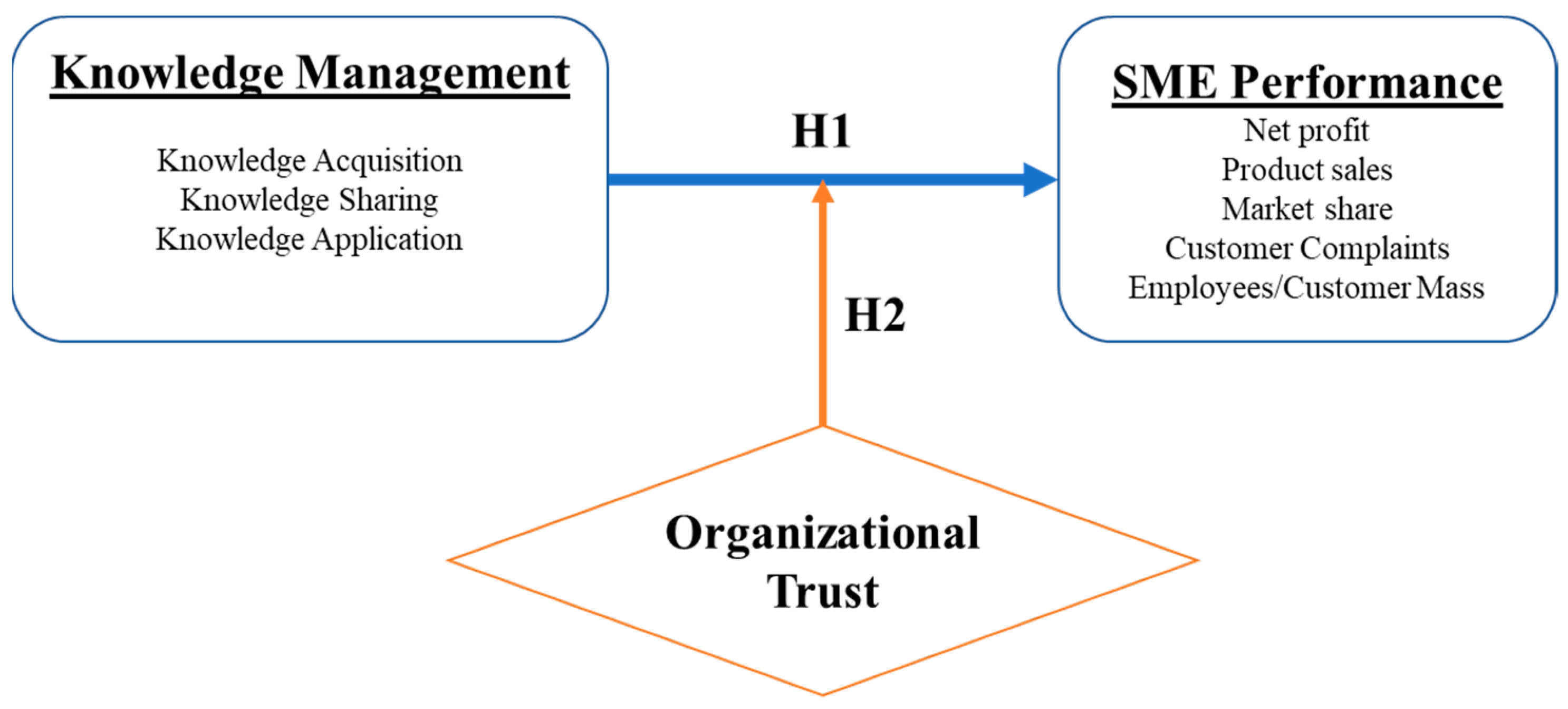

In order to address the gap in the existing literature on KM, this study aims to test an empirical model that can serve as a reference for understanding the relationship between KM and firm performance. The study also aims to investigate the moderating effect of trust in this relationship in the Algerian Food & Beverage SMEs context. This can provide a better understanding of organizational performance in these companies.

We choose Algerian Food & Beverage SMEs (F&B SMEs) for many reasons. First, Algerian SMEs have existed for a long time under the system of oil income, in which they rely on state subsidies to assure their survival. This situation harms their competitiveness and causes a continuous loss of knowledge capital [

15]. These state subsidies placed Algeria among the countries with the lowest knowledge and innovation capacities in Africa (it ranks 18th among the 19 economies in Northern Africa and Western Asia) [

16]. Second, the growth of SMEs with a minimal experience in the field of research and development (R&D) and knowledge management constitutes a significant issue for Algeria. A lack of knowledge creation and sharing is noticed in all industrial SME activity branches and is considered the primary reason for their poor performance. This problem becomes more complicated for SMEs when relationships lack trust and, therefore, become the main obstacle to using knowledge to improve performance. Eventually, by considering this context’s differences in values, principles, business practices, and culture, we expect to provide interesting findings vis-à-vis the empirical model of this study. Based on those explanations, the research questions are:

The purpose of this study is to contribute to the field of KM and performance both theoretically and practically. Firstly, the study aims to provide a broader understanding of how KM can improve performance. Secondly, it will help managers comprehend the significance of trust as a mediator in the connection between KM and performance. Lastly, it will expand the scope of KM research by examining concepts developed in SMEs in developing countries such as Algeria.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. We first analyze prior research on knowledge management, performance, and the trust effect that permits us to articulate our research hypotheses. Secondly, we provide a complete overview of the methodologies employed. Finally, we present our findings and discuss the practical and theoretical ramifications and limitations that permit us to make recommendations for future studies.

4. Analysis and Results

The data collected for this study were quantitatively analyzed with SmartPLS. The study tested two-step approaches that were adopted for evaluation and reporting PLS-SEM results. These two-step approaches are (1) assessment of the measurement model (Outer model) and (2) assessment of the structural model (Inner model), as recommended by Henseler et al. (2009) [

58]. For the assessment model, two types of validity were tested to obtain construct validity. First, factor loading (item reliability), composite reliability (CR), Cronbach’s alpha, and average variance extracted (AVE). Second, discriminant validity was employed.

Table 3 displays the composite reliability coefficients for each of the latent variables of this study.

As indicated in

Table 3, the composite reliability coefficient for each of the latent variables ranged from 0.927 to 0.946; this suggests the adequate internal consistency reliability of the measures. Moreover, Hair et al. (2021) [

59] suggested that factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) are the three critical assessors of convergence validity. All of them fit the required measures, as illustrated in the following table.

Discriminant validity was tested, as shown in the following (

Table 4). The results reveal discriminant validity for the constructs in this study. Overall, the measurement model illustrates adequate convergent validity and discriminant validity, as well.

Nevertheless, Cohen (1988) [

60] claimed that the R-square value for the endogenous latent variable is considered weak if it is lower than 0.02, moderate in 0.13, and substantial in 0.26. However, according to Falk & Miller (1992) [

61], an R-square value of 0.10 is acceptable. Consequently, Chin (1998) [

62] suggested that the R-squared value of 0.60 can be considered substantial, 0.33 moderate, and 0.19 weak. The R-squared value for the present study is reported in the following

Table 5.

Table 6 illustrates that the effect size of knowledge management was 0.097. The guidance of F2 assessment of the exogenous latent constructs of the present study on SME performance can be considered small for knowledge management.

The Q2, however, is a criterion to measure how well a model predicts. The Q2 value is obtained by using the blindfolding procedure for a specified omission distance. In other words, Q2 is a criterion to measure how well a model predicts the data of omitted cases. Hair et al. (2021) [

59] claimed that the blindfolding procedure is usually applied to endogenous constructs with a reflective measurement model. As the endogenous latent variable of the present study is reflective, a blindfolding procedure was applied to the endogenous latent variable. Henseler et al. (2009) [

58] stated that in a research model where the Q2 value is larger than zero, the model has a predictive relevance, as shown in

Table 7.

The study also tested the direct path by applying a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 re-samples to test the significance of the regression coefficients (

Table 8). Knowledge management is significant in SME performance (β = 0.173. t = 3.685.

p < 0.00). Therefore, the first hypothesis is accepted. Similarly, the study illustrated a moderating influence of organizational trust between knowledge management and firm performance (β = 0.103. t = 6.734.

p < 0.000). Thus, the second hypothesis is fulfilled.

5. Discussion

The first research question pointed out whether knowledge management positively influences SMEs’ performance. Based on our results, knowledge management is a good predictor of an SME firm’s performance. In fact, once knowledge is properly capitalized (categorized, protected), continuously enriched (acquisition and creation), and properly valued (applied/reused, shared, and transferred), its impact results in a significant minimization of errors and disruptions throughout the SME’s operating process. As a result, SMEs must prioritize KM by managing their intellectual resources to achieve optimal overall performance, ensuring that the firm stays efficient and competitive in the face of market fluctuations.

Furthermore, because performance is a contextual concept in the context of SMEs, the influence of knowledge management is dual. On the one hand, it has an impact on financial performance by rationalizing managerial decisions and ensuring that these decisions are implemented by members of the company. Knowledge management, on the other hand, influences non-financial performance by providing up-to-date production information and addressing issues creatively and in record time, as well as by enhancing and renovating products.

The findings are in line with the results obtained by prior research by Lee and Choi (2003) [

63] and Ghalomi et al. (2013) [

41], which dealt with the positive impact of the knowledge management process on SMEs’ performance. They considered knowledge management as a resource considered the most valuable asset and an essential competitive factor in organizations. Likewise, Masa’deh et al. (2017) [

64] maintained that knowledge management has strategic importance in developing unique organizations’ capacities and providing them with a sustainable competitive advantage. Cerchione et al. (2017) [

2] investigated the impact of knowledge management on SMEs’ performance, and the results showed a positive and significant relationship between these constructs. These results are consistent with the findings of Mohrman et al. (2003) [

39], who extended the concept of organizational effectiveness to financial measures and discovered a weak positive relationship between the extent to which organizations created and used knowledge and overall organizational performance, including financial measures. However, by combining a wide range of financial and non-financial indicators, the strength of the association may have been diminished. Mehrez et al. (2021) [

65] and Rezaei et al. (2021) [

66], for their part, confirmed the positive impact of KM and performance, and determined the factors affecting this relationship, such organization learning, intellectual capital, human capital, information technology, soft total quality management, strategy, and structure.

Consequently, in SMEs that face severe competition and accrue significant delays in industrial production, knowledge creation and exchange is a critical competitive advantage and an effective solution to their strategic and operational difficulties. The hypothesis of the impact of knowledge management on SMEs’ performance was accepted. This shows the importance of knowledge in improving the performance and promotion of the organization.

Hypothesis two states that organizational trust moderates the effect of knowledge management on SMEs’ performance. In fact, from the perspective of knowledge management, the creation process of collective representation and learning needs more human “trust” than analytical skills. The hierarchical organizations that prevailed in a production system (procedures, control) have no legitimate power over the flow of knowledge. Based on these considerations, the organization does not manage knowledge in the same way that it manages an object; rather, it manages conditions under which knowledge can be formed, codified, exchanged, validated, and so on. Trust is one of the critical conditions that facilitates the sharing of confidential information among employees because it diminishes the perceived risk of opportunism and the need to hide sensitive information.

The result confirms the moderating role of organizational trust in the knowledge management and firm performance relationship. This result is supported by Verma and Sinha (2016) [

67], Afzal and Afzal (2014) [

45], and Oh (2019) [

9], who found that trust moderated knowledge sharing and team performance relationships. The development of interpersonal trust among employees can lead to the effective implementation of KM, which increases the firm’s performance. These findings are in accordance with RBV theory, mentioned in Hypothesis Two. Organizational trust is, therefore, a crucial factor in this relationship; it is the glue that strengthens the employees’ relationship and motivates them to apply effective knowledge management in the firm to achieve its goals [

12] and enhances its performance [

51].

Table 9 summarizes what was discussed and provides a brief overview of the various findings of earlier research compared to our findings.

7. Conclusions

As a developing country, Algeria confronts many challenges, including a high unemployment rate, high costs of food importation, a high rate of SME bankruptcy, and economic instability. Based on this, SMEs are considered a magic wand and an excellent source for the growth and elimination of these challenges. However, due to the studied factors, SMEs in Algeria are still underperforming. The current study was undertaken to examine the internal intangible resources of knowledge management and organizational trust as predictors to enhance the low performance of SMEs.

The first research objective was to investigate the relationship between knowledge management and firm performance. The results showed a positive relationship, indicating that knowledge management is a good predictor of success in SMEs’ performance in Algeria. Thus, the owners/managers should emphasize issues related to knowledge acquisition, knowledge sharing, and knowledge application. The second research objective was to determine the moderating influence of organizational trust in knowledge management and firm performance. Based on the results, organizational trust resulted as a moderator for the knowledge management–firm performance relationship.